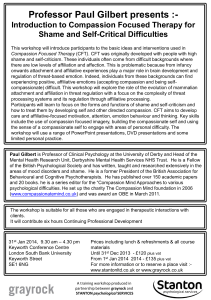

Psychotherapy Research ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tpsr20 Compassion focused therapy in a university counseling and psychological services center: A feasibility trial of a new standardized group manual Jenn Fox , Kara Cattani & Gary M. Burlingame To cite this article: Jenn Fox , Kara Cattani & Gary M. Burlingame (2020): Compassion focused therapy in a university counseling and psychological services center: A feasibility trial of a new standardized group manual, Psychotherapy Research, DOI: 10.1080/10503307.2020.1783708 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1783708 View supplementary material Published online: 25 Jun 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 6 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tpsr20 Psychotherapy Research, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1783708 EMPIRICAL PAPER Compassion focused therapy in a university counseling and psychological services center: A feasibility trial of a new standardized group manual JENN FOX, KARA CATTANI, & GARY M. BURLINGAME Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA (Received 27 January 2020; revised 30 May 2020; accepted 11 June 2020) ABSTRACT Objectives: The feasibility and acceptability of a new Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) group protocol were assessed in a university counseling and psychological services (CAPS) center. Outcome measures included mechanisms of change, compassion, and general psychiatric distress. Method: Eight transdiagnostic CFT groups composed of 75 clients met for 12 weekly sessions. Clients completed measures of fears of compassion, flows of compassion, self-reassurance, selfcriticism, shame, and psychiatric distress at pre, mid, and post time points. Self-report feasibility and acceptability data were collected from therapists and clients, respectively. Significant and reliable change was assessed along with exploratory analysis of CFT mechanisms of change using correlational analysis. Results: Significant and reliable change was found for fears of self-compassion, fears of compassion from others, fears of compassion to others, self-compassion, compassion from others, self-reassurance, self-criticism, shame, and psychological distress. Improvements in fears and flows of compassion predicted improvements in self-reassurance, self-criticism, shame, and psychiatric distress. Conclusion: The new CFT group protocol appears to be feasible, acceptable, and effective in a transdiagnostic CAPS population. The identified mechanisms of change support the theory of CFT that transdiagnostic pathological constructs of self-criticism and shame can improve by decreasing fears and increasing flows of compassion. Keywords: group psychotherapy; mental health services research; outcome research Clinical or methodological significance of this article: Compassion focused therapy—CFT research to date has been based on different, non-standardized protocols, making it impossible to draw clear conclusions across studies. The present study is the first to test a standardized group protocol created by the developer of CFT, Paul Gilbert. Each of the 12modules not only captures the core CFT components but also has a fidelity checklist to insure reliable delivery and make further replication possible. CFT is a trans-diagnostic model targeting self-criticism, shame and blame that have been shown to be highly correlated with psychiatric distress. The results of this study demonstrate that the new protocol replicates past effects on self-criticism, shame, and blame along with larger effects on psychiatric distress measured by the OQ-45. The standardized manual with additional therapist helps material enables CFT groups to be run with fidelity checks in clinical practice. Research on compassion has found a number of positive associations, such as positive correlations with mental health (e.g., MacBeth & Gumley, 2012) and social relationships (e.g., Yarnell & Neff, 2013). Not surprisingly, a variety of compassion-based treatments have been created in the past few decades including Compassion-Focused Therapy (Gilbert, 2014); Mindful Self-Compassion (Neff & Germer, 2013); Compassion Cultivation Training (Jazaieri et al., 2013); Cognitively Based Compassion Training (Pace et al., 2009); Cultivating Emotional Balance (Kemeny et al., 2012); and Compassion and Loving-Kindness Meditations (e.g., Hoffmann et al., 2011). A recent meta-analysis (Kirby et al., 2017) of compassion-based Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Gary M. Burlingame Brigham Young University, 238 TLRB, Provo, UT 84602, USA. Email: gary_burlingame@byu.edu © 2020 Society for Psychotherapy Research 2 J. Fox et al. interventions found moderate pre–post effect sizes on measures of compassion and psychiatric distress (i.e., depression, anxiety) with both wait-list and active control comparisons. These authors note particular promise for Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT). CFT is an integrated, evolution-informed biopsychosocial approach which combines traditional Buddhist teachings about mindfulness with compassion. It’s theoretical underpinnings include attachment theory, evolutionary psychology, and social mentality theory (Gilbert, 2014). CFT recognizes that humans evolved with a more advanced set of caring behaviors than other mammals since our young are dependent on parents far longer. These caring behaviors correspond to the physiological responses of soothing and reassurance and are linked to the autonomic nervous system and frontal cortex (Porges, 2017). Compassion is a direct result of this strong caregiving motivation in humans. Indeed, compassion in CFT is defined as “sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a desire to try to alleviate and prevent that suffering.” By activating these compassion processes, CFT helps clients activate their innate caregiving processes and the physiological systems that decrease one’s sense of threat and self-criticism and increase one’s sense of calm, reassurance, and emotion regulation. Following the definition of compassion as sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it, CFT cultivates each of component. First, clients work to develop a motivation to engage with suffering, their ability to approach and tolerate it. Second, clients are assisted in cultivating a corresponding commitment to act in a way to try to alleviate and prevent suffering along with the skills to do this successfully (Gilbert, 2014). Therapists work with clients to facilitate activation of the client’s caring motivational system by developing insight and tolerance of emotions and working through fears, blocks, and resistances to compassion. CFT uses psychoeducation, emotional modeling, meditative and imagery practices, and experiential interventions to help clients gain insight and build compassionate capacity (Gilbert & Irons, 2005). Many of these processes are utilized in other therapies, but CFT emphasizes that they must be experienced with a compassionate, prosocial affect in order to obtain the desired physiological and psychological impact. CFT was developed to address the transdiagnostic pathological processes of self-criticism and shame that can contribute to and maintain a range of mental health problems (Gilbert & Procter, 2006). The association between shame, self-criticism, and psychopathology has been well-established (e.g., Allan & Gilbert, 1997; Gilbert et al., 2010; Kelly & Carter, 2013; Lucre & Corten, 2013; PintoGouveia et al., 2014), particularly with depression (e.g., Kelly et al., 2009; Marshall et al., 2008). Selfcriticism is the perception of the self as inadequate or inferior leading to internal dialogue directed at self-correction, self-attacking, or self-hatred (Castilho et al., 2017). Shame is the perception of our self as unattractive, undesirable, incompetent, or inadequate with the belief that we are creating negative emotions in the mind of the other—anger, disgust, contempt, or ridicule (Gilbert, 2007). CFT counteracts self-criticism and shame by helping clients build the capacity to experience compassion, thus activating the caregiving system to regulate and reassure the self. CFT transdiagnostic research has found that CFTI is associated with significant reductions in symptoms such as anxiety, depression, self-criticism, shame, inferiority, submissive behavior, and overall distress as well as increases in self-compassion, self-esteem, and self-reassurance (e.g., Braehler et al., 2013; Gilbert & Procter, 2006; Heriot-Maitland et al., 2014; Judge et al., 2012; Laithwaite et al., 2009; Lucre & Corten, 2013; Mayhew & Gilbert, 2008). CFT groups have also been shown to be an effective group intervention (e.g., Ashworth et al., 2011; Braehler et al., 2013; Gale et al., 2014; Lucre & Corten, 2013; Mayhew & Gilbert, 2008) in recent transdiagnostic group research (Cuppage et al., 2018; Heriot-Maitland et al., 2014; Judge et al., 2012; McManus et al., 2018). Transdiagnostic groups are beneficial on two fronts. First, transdiagnostic groups composed of mixed anxiety or mood disorders are easier to create in many practice settings compared to homogenous groups. Moreover, available evidence suggests that transdiagnostic groups produce equivalent outcomes compared to single-diagnosis groups (Burlingame et al., 2013). Indeed, transdiagnostic groups are often composed of individuals with either anxiety or mood disorders. Stated differently, CFT transdiagnostic groups allows clients with similar complaints (e.g., anxiety disorders) to benefit from an effective intervention. By removing the restriction of membership to a single diagnosis (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder), one facilitates quicker access to treatment. Second, clients with differing diagnoses may be particularly well-suited for CFT groups since the treatment targets common underlying psychological constructs (i.e., shame and self-criticism), rather than symptoms associated with a specific psychiatric diagnosis. Despite the significant research base for CFT, it has yet to be assessed in a university counseling and psychological services (CAPS) center. Group treatments in CAPS centers are often transdiagnostic due Psychotherapy Research 3 to unique characteristics of this clinical population (Ribeiro et al., 2017). More specifically, a typical CAPS center service mandate includes immediate or short-term access, which often leads to reliance on transdiagnostic groups. CAPS service mandates also require service to both the clinically distressed and those who present with subclinical distress. Thus, this clinical setting may be a particularly good match to test the transdiagnostic CFT focus. To date, research has only focused on non-clinical university populations with CFT leading to increased self-compassion and decreased negative thoughts and emotions (Arimitsu, 2016). However, no studies have directly implemented CFT interventions in a CAPS center. Although CFT has been studied for decades, several limitations have prevented it from producing high quality, adequately powered randomized controlled trials (RCT). The largest and most pressing concern is the lack of a standardized manual. Researchers trained in CFT by Dr. Gilbert have created and tested various treatment protocols for compassion focused therapy (e.g., Braehler et al., 2013; Gilbert & Procter, 2006; Judge et al., 2012; Lucre & Corten, 2013). However, there is little consistency in content presented, exercises used, and number of sessions among these protocols, and each was typically used in a single study with no replication. There is an inherent difficulty in manualizing CFT since it is multi-modal and integrates processes across developmental psychology, social psychology, and more traditional psychotherapies. Given this rich theoretical foundation, CFT proponents argue against an overly rigid or mechanical therapy manual. A second limitation is that many compassion studies fail to measure protocol adherence to determine the fidelity of intervention delivery (Kirby et al., 2017); standard practice in evidence-based research insuring reproducibility. Stated differently, without a standardized manual, CFT research has been stuck in the feasibility stage and unable to move into the RCT stage where protocol fidelity is the gold standard. Another limitation in CFT research is inadequate assessment and testing of the proposed mechanisms of change. For instance, CFT theory posits that reducing an individual’s fears of compassion leads to an increased ability to engage in the three flows of compassion, which, in turn, will lead to a reduction in the primary outcomes of shame and self-criticism. After these changes occur, decreased psychiatric distress is expected. A few studies have investigated these mechanisms of change and found promising change in primary outcomes (self-reassurance, self-criticism) and psychiatric distress (Cuppage et al., 2018; Sommers-Spijkerman et al., 2018). However, past research has failed to simultaneously and temporally measure how changes in the fears and resistances to compassion predict changes in the three flows of compassion and if these differentially predict the primary outcomes of CFT. Current Study The current study addressed the above limitations by creating a standardized group manual for a CAPS population (Cattani et al., 2020) that was based upon a larger manual from the CFT developer, Paul Gilbert and his colleagues (in press). After developing the CAPS manual, we next focused on verifying the feasibility and acceptability of this manual from both a group leader and client perspective. Finally, we simultaneously assessed CFT mechanisms of change (three fears and flows of compassion); primary outcomes (self-reassurance, self-criticism, and shame); and distal outcome (psychiatric distress). The decision to focus on three rather than the traditional single primary outcome was made based on the fact that CFT is a transtheoretical intervention designed to target change in all three outcomes. Furthermore, previous literature has measured these three outcomes (Joeng & Turner, 2015; Kirby et al., 2019; Matos et al., 2017; Naismith et al., 2020) with promising results. Finally, we examined if measures specifically designed for CFT by Gilbert produced the same change patterns as measures of the same construct developed by others. This analysis was intended to assess for measure bias, specifically exaggerated CFT effects on Gilbert measures. The primary aims of the current study were to: (1) assess the feasibility and acceptability of a new standardized 12-session transdiagnostic group CFT protocol in a CAPS center from both a client and therapist perspective; (2) determine whether the CFT protocol showed the anticipated effect of significant increases in flows of compassion and self-reassurance and decreases in fears of compassion, selfcriticism, shame, and psychiatric distress; and (3) explore if the early, middle, and late change in proposed mechanisms of change (i.e., decreases in fears of compassion and increases in flows of compassion) predicted longitudinal change in primary outcomes (i.e., decreases in self-criticism and shame) and distal outcome (i.e., decreases in psychiatric distress) as predicted by CFT theory. Method Clients Clients were students presenting for treatment at a university CAPS center. Inclusion criteria included 4 J. Fox et al. a primary presenting concern related to shame or selfcriticism, willingness to have group be their primary mode of treatment, and pre-treatment distress at a clinical level (OQ-45 at or above 64). As CFT is transdiagnostic, client concerns relating to self-criticism and shame were considered more important than a specific diagnosis so no standardized diagnostic interview was used. Loss of clients over time occurred due to students choosing to discontinue in the study, failing to complete measures, or dropping out of groups. We began with 109 clients who were registered for CFT groups but only 75 completed initial measures and 45 completed the entire assessment battery and treatment (Figure 1). Of the 75 clients who completed measures, 73.5% were female and race was 85.5% Caucasian, 7.2% Hispanic, 3.6% multi-racial, 2.4% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 1.2% Asian. Clients ranged in age from 18 to 29 with a mean of 22.7; 99% identified as Christian. Primary presenting complaints were based upon client responses to the Student Concerns Questionnaire (Pedersen & Smart, 2007) and were as follows: depression (28%), perfectionism (20%), anxiety (11%), interpersonal (9%), stress (4%), identity development (4%), trauma (4%), adjustment (2%), self-harm (2%), OCD (2%), emotional dysregulation (2%), and assorted others (12%). Treatment CFT first uses psychoeducation to help clients understand the nature of the human mind and the benefits of mindfulness and compassion (Gilbert, 2009). Indeed, considerable time is invested in early sessions linking the human brain, genetics, and life experience to emotional regulation and how CFT will help client use their bodies to support their minds. Clients then build the compassion skills through exercises, imagery, and guided meditation which are later used to address symptom distress (Gilbert & Choden, 2013). Each session includes didactic, experiential, and discussion portions supported by handouts (Gilbert, 2017). At the end of each session, worksheets for compassion practices and audio recordings of meditations and imagery exercises to be completed between sessions are handed out. Table I briefly overviews the topics and key elements of the 12 CFT session in our manual (Cattani et al., 2020). Measures Feasibility and Acceptability. Fidelity checks were created for each session that contained a brief description of the core psychoeducation, skill, and behavioral practices. Each leader independently completed these checklists immediately following each session to check for inter-rater reliability. Observer ratings of fidelity were not completed as it was outside the scope of this feasibility study as well as privacy concerns of the members of the group who elected not to participate in the study. However, a new CFT competency measure was created as a result of this study which will be used in future studies with this manual. At the end of each session, clients were asked to complete a brief five item questionnaire relating to acceptability (see online supplement Figure 1). Figure 1. Flow of study participants. Mechanisms of Change. Fears of Compassion (FCS; Gilbert et al., 2011) is designed to assess the fears, blocks, and resistances to compassion. The FCS has three subscales: Fear of Compassion for Psychotherapy Research 5 Table I. Overview of group sessions. Session Topic Key Elements 1. Compassion Exploration of compassion: definition, fears of compassion 2. Emotion Systems Influences of evolved brain, genetics, and social context on behavior Three emotion systems 3. Mindfulness & Attention Using attention intentionally for awareness and amplification Use of soothing system to regulate activating systems 4. Safeness vs Safety “Safe place” imagery “Compassionate Other” imagery 5. Compassionate Self “Compassionate Self” imagery 6. Self-criticism Exploration of self-criticism—purpose and effects Using “compassionate self” imagery to address self-critic 7. Shame Exploration of shame & guilt Addressing shame & guilt with Compassionate Self 8. Multiple Selves Exploring multiple emotions in threat system Addressing multiple emotions through Compassionate Self 9. Compassion for Self Cultivating compassion for self Compassionate letter writing 10. Compassion for Others Shifting from empathy to compassion Compassionate forgiveness 11. Compassionate Communication Understanding and expressing needs and feelings Asking for needs & responding to requests compassionately 12. Continuing Compassion Review and relapse prevention Wrap-up and goodbyes Self, Fear of Compassion from Others, and Fear of Compassion for Others. Items are rated on a fivepoint Likert scale (0 = Don’t agree at all, 4 = Completely agree). Gilbert reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 for fear of compassion for self; 0.87 for fear of compassion for others, and 0.78 for fear of compassion for others. A reliable change index—RCI (Jacobson & Truax, 1991) for each subscale was calculated at: 8.4 for fears of compassion for self, 6.9 for fears of compassion for others, and 7 for fears of compassion from others. The Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales (CEAS; Gilbert et al., 2017) measures the ability to engage with and act on compassion for self, compassion for others, and compassion from others. Clients rate each statement according to how frequently it occurs on a scale of 1–10 (1 = Never; 10 = Always). The scale has recently been validated with a good Cronbach’s alphas and factor structure. A RCI for each subscale were calculated as 12.4 for compassion for self, 7.2 for compassion to others, and 7.6 for compassion from others. Primary Outcomes—CFT Measures. Forms of Self Criticism and Self Reassuring Scale (FSCRS; Gilbert et al., 2004) has two subscales for self-criticism: Inadequate self, which measures the sense of personal inadequacy, and Hated self, which focuses on the desire to hurt or persecute the self. A third subscale, Reassured Self, measures the individual’s ability to be self-reassuring and supportive when things go wrong. Items are scored using a five-point scale (ranging from 0 = not at all like me to 4 = extremely like me). Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales are .90 for inadequate self, .86 for hated self and .86 for reassured self (Gilbert et al., 2004). A RCI for each subscale was calculated as 4.3 for reassured self, 5.2 for inadequate self, and 3.4 for hated self. Primary Outcomes—Independent measures. Depressive Experiences Questionnaire 48 McGill Revision—Self Criticism Subscale (DEQ; Santor et al., 1997) assesses various self-criticism on a sevenpoint Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Reliability coefficients were measured at .72 for men and .76 for women. A RCI was calculated as 15.6. Tests of Self-Conscious effect —Shame Subscale (TOSCA; Tangney et al., 2000) asks respondents to rate the likelihood of their shame response to brief scenarios on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not likely”) to 5 (“very likely”). Cronbach’s α for the full 16-item TOSCA-3 was reported ranging from .76 to .88 for shame-proneness in three samples of university students (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). A RCI was calculated as 7.2. Distal Outcome. Outcome Questionnaire-45 measures client distress on interpersonal relations, symptom distress, and social role questions on a 7point Likert scale. The OQ has a reported internal consistency of .93 and a test-retest reliability of .84 (Lambert & Ogles, 2004). The reliable change index for the OQ has been calculated as 14 points. Procedure The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board at Brigham Young University. CAPS clients were referred to the CFT groups by their individual therapists. Clients were assigned to groups based on schedule availability. As group was 6 J. Fox et al. the primary form of treatment, clients were asked to meet with their individual therapists no more than once every three weeks. The 12-session weekly outpatient CFT groups were led by 2 doctoral-level psychologists experienced in group therapy. Three primary leaders (JF, KC & GB) were trained by Gilbert and his colleagues in CFT during an extended professional development leave (3 months) in the United Kingdom and 8 co-leaders engaged in CFT self-study prior to the group. The primary group leaders received weekly supervision from Dr. Gilbert to address questions about the protocol and clinical issues. All leaders met each week as a treatment team to discuss adherence and acceptability issues with the primary leaders and to participate in CFT group supervision led by the three Gilbert-trained therapists. Groups had 7–14 clients with an average of 9.4 clients per group, met for 120 min, with an average of 11.5 sessions across the eight groups; four groups combined two sessions due to holidays and final exams. Clients were sent a Qualtrics survey link to sign an informed consent form and complete the first round of assessments; the same link was sent after the 6th (mid-treatment) and final session (post-treatment) and clients completed a weekly OQ-45 online. Clients were considered dropouts if they missed three consecutive sessions. However, after inspecting the dropout data, we subdivided it into “partial” if they attended at least half of the sessions and “full dropout” if they attended less than half the sessions. Data Analyses Pre-treatment client data were included for analysis if they met inclusion criteria and had a valid and complete pre-assessment within 21 days of the first session. These criteria resulted in 75 clients being included in analyses for mechanisms of change and primary outcomes. Missing data for mid and post assessments used the last observation carried forward rule. The distal outcome (OQ) had more missing data than other measures because it was administered through CAPS’ existing processes, rather than by the researchers in the CFT battery; CAPS typically has a low level of completion of the OQ. Based on the CAPS center’s data analyst who is an OQ expert (D. Erekson, Ph.D., personal communication, August 30, 2018), a 30-day window before and 15-day after the first session was used for pre-treatment distress and, a 15-day window before and 30-day after was used for the final session. These screening criteria resulted in 30 clients contributing OQ data for analyses of distal outcome. All analyses were done in SPSS 20 at p < .05. Feasibility data were examined descriptively using means and standard deviations. Acceptability from the client feedback forms for each session was also examined using means and standard deviations but average session attendance and attrition rates were also used as indirect measures of client acceptance. These rates were compared to average center rates using the remaining 25–30 groups run during the same semester. Due to the nested nature of group data where individuals are situated within groups, we calculated the variance due to groups to determine if a significant intra-group dependency was present using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and whether the analyses needed to account for nesting. There were no significant group effects. All measures were assessed for change between pre-, mid-, and post-treatment time points. Measures that produced both overall and subscale scores (FCS and CEAS) were analyzed with repeated measure MANOVAs; Wilks’ lambda and Huynh-Feldt are reported for multivariate and univariate tests, respectively. Measures that produced only subscales level (FSCRS) were analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVA; Wilks’ lambda is reported. Independent measures of the primary outcome (DEQ-self-criticism and TOSCA Shame) assessed at pre- and post-treatment and analyzed using paired t-tests while the distal outcome measure (OQ-45) assessed at pre-, mid-, and post-treatment was analyzed using a repeated-measures ANOVA; Wilks’ lambda is reported. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d. Pearson correlations were used to explore the association between change in mechanism of change measures and change in self-criticism, shame, and psychiatric distress. Results Feasibility and Acceptability Our first aim was to establish the feasibility and acceptability of this new protocol. The average therapist fidelity scores for the CFT psychoeducation, skill and behavioral practices listed for each session ranged between “mostly present” and “fully present” (M=2.33 out of 3.00, SD=0.17; see online supplement Table 1). Similarly, average client session ratings on the 5-feedback items was 4.11 out of 5.00 possible (SD = 0.53; see online supplement Table 2). On average, clients attended 56% of sessions. Of the 73 who attended at least one group, nearly two-thirds (61.6%) completed the protocol (49.3% full completers and 12.3% Psychotherapy Research 7 Table II. All subscale means for pre, mid, and post time points. Pre Mid Post Measure Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD FCS Fears of self-compassion Fears of compassion from others Fears of compassion to others 28.08 24.20 13.63 11.68 9.84 6.03 24.21 22.49 12.79 11.46 9.96 5.69 21.81 20.97 12.07 12.47 10.33 5.72 CEAS Self-Compassion Compassion from Others Compassion to Others 49.23 54.95 78.89 10.03 16.11 10.95 54.00 59.39 77.59 11.70 18.01 10.99 57.51 59.39 78.03 14.20 17.61 9.87 FSCRS Reassured Self Hated Self Inadequate Self 10.77 9.65 28.61 5.57 5.04 5.32 11.91 8.68 26.09 6.06 5.19 6.90 13.27 7.93 23.65 6.81 5.19 8.36 139.11 11.99 131.92 16.32 TOSCA Shame 39.64 5.00 37.99 5.13 Outcome Questionnaire 75.72 22.57 70.69 24.77 DEQ Self-Criticism partial completers). This attendance pattern is similar to the semester rates from the 25–30 groups/week at the counseling center during the course of the study, with absences typically due to the student’s exam schedules and trips out of town for holidays or family visits. Significant and Reliable Change Since this was the first study to use CFT in a CAPS center, we first report the means and standard errors for all subscales from our sample (Table II) and descriptively compare these to pre-intervention means from the CFT literature (online supplement Table 3). Our clients average pre-treatment scores typically fell between literature-based values for non-clinical and clinical samples on flows and fears of compassion as well as shame and self-criticism. However, our clients scores indicated unusual ease in compassion to others (higher than both non-clinical and clinical population), with pre-treatment scores closer to what would be expected at post-treatment, suggesting a “ceiling effect” for compassion to others. Additionally, on the independent measure of self-criticism (DEQ), our clients had significantly higher ratings than both the literature-based nonclinical and clinical samples. For psychiatric distress (OQ) our clients matched the clinical norm for CAPS. We expected that the new standardized CFT protocol would replicate past research findings and indeed, we found significant change on all but one subscale (Table III). We also calculated pre–post 74.88 24.20 effect sizes finding one large, nine medium and four small effects. The absence of change on the compassion to others subscales is likely related to the pre-treatment ceiling effects noted above. We also calculated reliable change (see online supplement Table 2) and found a third of clients improving on compassion (self-compassion and compassion from others), fears (self-compassion) and self-criticism (inadequate self) measures. A fourth showed Table III. Significant change over time. Measure FCS 1 Fears of self-compassion Fears of compassion from others Fears of compassion to others 1 CEAS Self-Compassion Compassion from Others Compassion to Others FSCRS 2 Reassured Self Hated Self Inadequate Self DEQ Self Criticism3 3 TOSCA Shame Outcome Questionnaire 2 df F Sig. Cohen’s d 6 1.50 1.50 5.414 22.48 11.06 0.00 0.00 0.00 −0.60 −0.63 −0.43 1.80 8.50 0.00 −0.41 6 1.68 1.77 1.87 7.86 29.94 8.13 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.19 0.54 0.75 0.36 0.14 2 2 2 15.67 15.33 18.76 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.63 −0.62 −0.71 74 −2.26 0.00 −0.59 74 −2.05 0.00 −0.48 2 8.26 0.00 −0.63 Notes: 1Repeated measures MANOVA. 2 Repeated measures ANOVA. 3 Paired t-tests. 8 J. Fox et al. improvement on the remaining subscales assessing fears (compassion from others) and self-criticism subscales (hated self, self-criticism, and reassured self) with a small percent (12%) showing improvement in shame and nearly half improving on psychiatric distress measures. Relationship Between CFT Mechanism of Change and Primary Outcomes Since this is the first study to simultaneously measure CFT putative mechanisms of change (FCS & CEAS) and primary outcomes using both CFT (FSCRS) and independent measures (DEQ & TOSCA) in a CAPS population, we wanted to explore the relationship of change among these measures. This was done by correlating change on the CFT mechanisms of change (i.e., fears and flows of compassion) with change on primary outcomes (i.e., self-criticism and shame). Given that compassion to others did not show significant change, it was not considered. In interpreting the correlations there were a number of patterns we expected to find based on CFT theory that are summarized in online supplement Table 5. To summarize, we expected that early change (pre-mid treatment) in the mechanisms of change would predict later change (mid-post) in the primary outcomes; that is, that change in the mechanisms of change would precede a change in primary outcomes. Another expected CFT change pattern would be a simultaneous change in the mechanisms of change and primary outcomes. For instance, as clients shift in their flow of compassion, change in primary outcomes would begin at the same time and continue throughout therapy. However, we also outline change patterns that do not fit CFT theory (online supplement Table 5). Late change in the mechanisms of change should not occur in the presence of early change in the primary outcomes. For instance, according to CFT theory, early improvement in self-criticism should not occur before an increase in the flows of compassion. As predicted, both the fears and flows of compassion to self and compassion from others (online supplement Tables 6 & 7, respectively) had medium to large correlations with changes in shame, psychiatric distress, and both CFT and independent measures of self-criticism. These followed the predicted trend of changing simultaneously (e.g., early change in self-compassion predicted early change in self-criticism). Typically, the largest correlations were between overall change in both mechanisms of change and outcomes. Discussion The results herein supported the primary aims of this study: to create a feasible and acceptable manual that showed improvement that matched previous CFT studies and change patterns that provide indirect support for CFTs mechanisms of change. As reported by therapists and clients, the standardized 12-session manual was broadly feasible and acceptable in a CAPS center. Reliable change was found for the mechanisms of change (fears and flows of compassion), primary outcomes of CFT (self-criticism, shame, and self-reassurance), and distal outcome (psychiatric distress). Additionally, improvement in CFT mechanisms of change was associated with both primary and distal outcomes. The self-report fidelity data from therapists indicated that nearly all of the session material was delivered, supported by high-interrater agreement (>90%). While the therapists fell slightly short of “perfect self-report fidelity,” the protocol was judged to be feasible to administer in a CAPS center. Sessions 10 and 12 (online supplement Table 1) posted the lowest values (averaging at the “material mostly present” level) due to the need to combine the last few sessions for four of the groups. The weekly supervision session our team had with Gilbert provides support that the manual was implemented with fidelity, although formal fidelity checklists would have been superior. However, these supervision sessions also revealed the occasional need for deviation from the protocol for clinical reasons and each of these deviations were discussed with Gilbert. The clinicians ability to deliver nearly all of the session material addressed CFT proponents concern of an overly rigid and mechanical CFT manual. Indeed, the flexibility of manual implementation led to a descriptive mantra from our Gilbert supervision: “don’t sacrifice a clinical moment for the manual.” For example, CAPS clinicians felt the flexibility to explore client resistance to addressing self-compassion or self-criticism while still implementing the majority of the CFT material in the standardized manual. Acceptability based upon aggregate client ratings of individual sessions suggests that the treatment was generally well-received and acceptable with little deviation across the 12-sessions (online supplement Table 2). The attendance data also supports acceptability with over a quarter of clients missing one or fewer groups and nearly 60% attending over half of the sessions. Client-recorded reasons for missed sessions were typical of our CAPS center (exams or project deadlines, visits to family, etc.) and the 38% considered full dropouts falls on the lower end of the CFT dropout range (10–80%) reported by Leaviss and Uttley’s (2015). The CFT Psychotherapy Research 9 literature actively discusses clinical reasons for attrition, including difficulties in confronting the fears and blocks of compassion (e.g., Gilbert, 2014; Lucre & Corten, 2013; Mayhew & Gilbert, 2008; McManus et al., 2018). Thus, our attrition rates, while comparable to other groups in our CAPS center, may also be the result of unique challenges inherent in the CFT protocol. Collectively, the client feedback, attendance, and completion rates suggest that clients found CFT sessions to be enjoyable, useful, and understandable. In addition, over 12% of the clients returned to the group after 3 or more consecutive absences (creating the need for our partial dropout category) which is another indicator of the acceptability of the protocol. How do University CAPS Clients “fit” Into the Existing CFT Literature? In general, CAPS clients occupy a unique position of being significantly more distressed than non-clinical and university samples on the mechanisms of change (fears and flows of compassion) but significantly less distressed than other clinical samples found in the CFT literature. It is worth noting that previous CFT studies often focused on severely distressed populations, including psychosis, personality disorders, and eating disorders. Stated differently, the existing CFT literature represents a very high level of distress ( e.g., Braehler et al., 2013; Gale et al., 2014; Heriot-Maitland et al., 2014). Thus, we were somewhat surprised by the near-clinical level of distress in our CAPS population on two compassion flows (self-compassion and compassion from others). The linear increase in perfectionism in college students over the past 30-years (Curran & Hill, 2019) may partially explain the clinical levels of distress in compassion we found. A different picture emerged when it came to compassion to others, our CAPS clients began treatment performing better than their non-clinical peer group and far better than clinical samples. This left little room for observable change (a ceiling effect). The most likely explanation for the unusually high compassion to other scores is that our clients attend a church-owned and operated university where over 98% of students are active in their faith. This faith places a heavy emphasis on service, kindness, and sacrifice for others. Thus, the unique culture of our clients creates a norm for compassion to others with unusual amounts of practice, making our sample unrepresentative on this compassion construct. There was a similar pattern of scores on the primary outcomes. Our CAPS scores on self-criticism and shame were significantly higher than nonclinical and undergraduate samples but generally lower than the clinical samples, although on some scales they were equivalent to general psychiatric distress matching CAPS norms. Thus, with the exception of compassion for others, our CAPS sample demonstrated clinical levels on all measures, albeit lower than past CFT clinical samples. Significant and Reliable Change in Compassion, Self-criticism and Shame The primary aim was to determine if the new CFT protocol led to significant pre-to-post change on measures of compassion, fears of compassion, selfreassurance, self-criticism, shame, and psychiatric distress. As expected, significant improvement was found on all subscales except for compassion to others. We compared the magnitude of change for CAPS to previous effect sizes in compassion-based intervention literature (Kirby et al., 2017) but, it is important to note three important differences between our effect sizes and those in Kirby et al. First, their meta-analysis examined several compassion-based interventions, not just CFT. Second, they only calculated change in overall compassion, while we examined both the fears and flows of compassion (to self and others, compassion from others) as well as unique CFT primary outcomes (e.g., reassured, hated, and inadequate self). Third, their effect sizes were drawn from comparisons of compassion interventions to waitlist control, while ours reflect pre–post change; the latter effect sizes produce larger values. Given these differences, the following comparisons should be viewed with caution. Published effect sizes for change in self-compassion (d = .70) were comparable with our study’s effect size (d = .75). However, published effect sizes for changes in overall compassion were smaller in our study (d = .14–.36) than in the meta-analysis (d = .55). Effect sizes for decreases in psychiatric distress were slightly higher in our study (d = .63) compared with the meta-analysis (d = .47). Taken together, these comparisons are promising for the new CFT protocol ability to produce comparable change to other compassion-based interventions. However, its important to keep in mind the limitations for comparison noted above. Predictive Abilities of Changes in Compassion The final aim was to explore improvement on CFT mechanisms of change (i.e., fears and flows of compassion) with change on primary (i.e., self-criticism 10 J. Fox et al. and shame) and distal outcomes (i.e., psychiatric distress). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between the three flows of compassion and the primary CFT outcomes of selfreassurance, self-criticism, and shame. We hypothesized that improvement in mechanisms of change would precede improvement in outcomes or, that change in both would occur simultaneously since increases in compassionate abilities might lead to a rapid reduction in self-criticism and shame. Given that our open trial status, we simply had an insufficient sample size to examine these relationships with more sophisticated analyses (e.g., mediation methods). Thus, we offer our findings from a descriptive perspective that might guide future research. Nearly all the correlations supported a change in mechanisms of change and primary outcomes occurring at the same time. In a few cases, change in the mechanisms seemed to occur before and predict a subsequent change in primary outcomes. These patterns of change were found on both the CFT measures of self-criticism as well as the independent measures of self-criticism and shame. Of note, the largest correlations were found in the CFT measures that assess the fears and flows of self-compassion. Thus, there is very preliminary evidence in support of the CFT theory that reducing clients’ fears of compassion and increasing their ability to engage and act in the flows of compassion may lead to an improvement in self-criticism and shame. passing of time. Clearly, the next step is to take the standardized CFT group protocol and test it against waitlist or known evidence-based group treatments (treatment-as-usual) controls in a randomized clinical trial to clarify its effectiveness. Another limitation was the reliance on self-report fidelity. However, the revisions made to the manual as a result of this pilot study led to a new CFT competency measure that will enable observer fidelity ratings in future research. Our clients were highly educated college students, white, young, religious, from mostly higher socioeconomic backgrounds and caution should be used in extending the results of this study to other populations. However, given the consistent success of CFT across a wide diversity of settings, ages, diagnoses, and countries (Kirby et al., 2017), it is likely that this CFT group protocol would have similar results in other populations. A final limitation was the difficulty inherent in doing research in a real-world clinical setting (e.g., groups being canceled for exam schedule or holidays, requiring sessions to be condensed). Such issues are common in clinical research and our results show the ability of our intervention to succeed in a realworld setting where flexibility is required and imperfection is inevitable. The results of this study are a testament to the potential of this intervention even without ideal research conditions. Future Directions Limitations Several limitations to this research should be considered. First, there were a number of constraints inherent in a feasibility trial. Of particular note, no previous data existed to conduct a power analysis, and there was no comparison group. Since our focus was testing a new standardized manual with a new population, we were unable to conduct a power analysis in advance. Efforts were made to compare the results of this study to existing literature, but as noted in the results section, our clients had some unique patterns of responding that appear to differentiate them from other populations. The findings herein provide preliminary data to support power analyses for future CFT studies with this manual and clinical population. Additionally, we had a single treatment condition with no control group so there is no way to determine how much change resulted from the intervention. However, since change took place over relatively short time period—a semester—and on outcomes targeted by treatment (shame and self-criticism), it seems unlikely that change can be entirely explained by the From the beginning, this feasibility trial was meant to launch a larger program of research. More specifically, if the CFT group protocol was found to produce promising results, the next step would be a randomized clinical trial (RCT). An additional benefit of this study was the creation of a revised group protocol using feedback from both therapists and clients. The protocol revisions produced by this study not only address CAPS transdiagnostic anxiety and mood groups, but also other CAPS homogenous clinical indications (e.g., eating disorders). The larger CFT manual (Gilbert et al., in press) is currently being applied to other clinical populations (e.g., seriously mentally ill, veteran, and LGBT+) in countries associated with the CFT cooperation (e.g., USA, Italy, Australia, and the Netherlands). This series of studies using a common manual will begin the process of building a stronger foundation for future RCTs. With the advent of a standardized CFT manual with a fidelity checklist, we have several thoughts regarding future research. First, adequately powered samples are essential for the future mediator and moderator analyses assessing the predicted Psychotherapy Research relationship between the mechanisms of change (i.e., fears and flows of compassion), primary (i.e., self-criticism and shame) and distal outcomes (i.e psychiatric distress). The findings herein are only suggestive and they need to be tested directly using adequately powered designs. Given CFTs incorporation of attachment theory, future studies might assess clients experience of social safeness and interpersonal connectedness to determine if change in these might facilitate movement from a competitive to compassionate stance (Vimalakanthan et al., 2018). The existence of a standardized CFT protocol also introduces a host of opportunities to understand the temporal change process. For instance, we need to examine CFT effects with respect to dose (how many sessions are needed for an effect) and practice (how much outside practice is needed for an effect). There is a dearth of CFT studies that have looked at CFT treatment effects using short- and longterm follow ups, and future RCTs to must assess this to understand if post-treatment effects are durable. Finally, we collected qualitative comments from our clients and plan on reporting on these in a subsequent publication. 11 Author contributions Jenn Fox, Gary Burlingame, and Kara Cattani contributed equally to the research program and senior authorship should be considered interchangeable. This study is part of a larger program of research created by Burlingame and Cattani, who orchestrated the vision, research design, international coordination, training, and funding required for the ongoing program of research. Fox took primary responsibility for the direct implementation of the study through managing team coordination, data collection and analysis, and this paper is based on her dissertation. Supplemental data Supplemental data for this article can be accessed https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1783708 ORCID Gary M. Burlingame 8275-4118 http://orcid.org/0000-0002- Conclusion Overall, this feasibility trial was deemed to be a successful first step for the new CFT group protocol. Therapists were able to administer the protocol with good fidelity, and their suggestions have been incorporated into a revised manual that will support future randomized clinical trials. Clients reported the sessions as enjoyable, useful, and clear and while CAPS client attendance was sporadic at times, there was a general pattern of returning to group even after missing several sessions, indicating that clients found value in the treatment. Significant results included increases in compassion and selfreassurance and decreases in fears of compassion, self-criticism, shame, and psychiatric distress with medium to large pre-to-post-treatment effect sizes. Finally, the mechanisms of change for CFT (three flows of compassion) predicted changes in self-criticism and shame, with most correlations being medium to large in size. Acknowledgement The authors would like to acknowledge the CFT coleaders—RD Boardman, Michael Buxton, Yoko Caldwell, David Erekson, Derek Griner, Corinne Hannan, Tyler Pederson, and Vaughn Worthen— along with Cameron Alldredge and Hal Svien who assisted in the data collection. References Allan, S., & Gilbert, P. (1997). Submissive behaviour and psychopathology. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36(4), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01255.x Arimitsu, K. (2016). The effects of a program to enhance self-compassion in Japanese individuals: A randomized controlled pilot study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(6), 559–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1152593. Ashworth, F., Gracey, F., & Gilbert, P. (2011). Compassion focused therapy after traumatic brain injury: Theoretical foundations and a case illustration. Brain Impairment, 12(02), 128– 139. https://doi.org/10.1375/brim.12.2.128 Braehler, C., Gumley, A., Harper, J., Wallace, S., Norrie, J., & Gilbert, P. (2013). Exploring change processes in compassion focused therapy in psychosis: Results of a feasibility randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 52(2), 199– 214. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12009 Burlingame, G., Strauss, B., & Joyce, A. (2013). Change mechanisms and effectiveness of small group treatments. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin & Garfield’s Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change, 6th Ed (pp. 640–689). Wiley & Sons. Castilho, P., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, J. (2017). Two forms of self-criticism mediate differently the shame-psychopathological symptoms link. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90(1), 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12094. Cattani, K., Griner, D., Erekson, D., Burlingame, G., Beecher, M., & Alldredge, C. (2020). Compassion focused group therapy for college counseling centers. Routledge Mental Health. Cuppage, J., Baird, K., Gibson, J., Booth, R., & Hevey, D. (2018). Compassion focused therapy: Exploring the effectiveness with a transdiagnostic group and potential processes of change. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 240–254. https://doi.org/10. 1111/bjc.12162 12 J. Fox et al. Curran, T., & Hill, A. (2019). Perfectionism is increasing over time: A meta-analysis of birth cohort differences from 1989 to 2016. Psychological Bulletin, 145(4), 410–429. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/bul0000138 Gale, C., Gilbert, P., Read, N., & Goss, K. (2014). An evaluation of the impact of introducing compassion focused therapy to a standard treatment programme for peoplewith eating disorders. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cpp.1806 Gilbert, P. (2007). Psychotherapy and counselling for depression (3rd ed). Sage. Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind: A new approach to the challenges of life. Constable & Robinson. Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12043 Gilbert, P. (2017). Compassion focused group therapy for college counseling centers. Compassionate Mind Foundation. Gilbert, P., Catarino, F., Duarte, C., Matos, M., Kolts, R., Stubbs, J., Ceresatto, L., Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Basran, J. (2017). The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-0170033-3. Gilbert, P., & Choden (2013). Mindful compassion. Using the power of mindfulness and compassion to Transform our Lives. Robinson. Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Kempel, S., Miles, J., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms style and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1348/01446650 4772812959 Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2005). Focused therapies and compassionate mind training for shame and self-attacking. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 263–325). Routledge. Gilbert, P., Kirby, J., & Petrocchi, N. (in press). Compassion focused therapy: Group therapy Guidance. Routledge. Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Irons, C., Bhundia, R., Christie, R., Broomhead, C., & Rockliff, H. (2010). Self-harm in a mixed clinical population: The roles of self-criticism, shame, and social rank. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(4), 563– 576. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466509X479771 Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84 (3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608310X526511 Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(6), 353–379. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cpp.507 Heriot-Maitland, C., Vidal, J. B., Ball, S., & Irons, C. (2014). A compassionate-focused therapy group approach for acute inpatients: Feasibility, initial pilot outcome data, and recommendations. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12040 Hoffmann, S., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. (2011). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological intervention. Clinical Psychology Review, 13, 1126–1132. Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12– 19. Jazaieri, H., Jinpa, G., McGonigal, K., Rosenberg, E., Finkelstein, J., Simon-Thomas, E., & Goldin, P. (2013). Enhancing compassion: A randomized controlled trial of a compassion cultivation training program. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14 (4), 1113–1126. Joeng, J., & Turner, S. (2015). Mediators between self-criticism and depression: Fears of compassion, self-compassion and importance to others. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(3), 453. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000071 Judge, L., Cleghorn, A., McEwan, K., & Gilbert, P. (2012). An exploration of group-based compassion focused therapy for a heterogeneous range of clients presenting to a community mental health team. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 5(4), 420–429. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2012.5.4.420 Kelly, A., & Carter, J. (2013). Why self-critical patients present with more severe eating disorder pathology: The mediating role of shame. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 52(2), 148–161. Kelly, A. C., Zuroff, D. C., & Shapira, L. B. (2009). Soothing oneself and resisting self-attacks: The treatment of two intrapersonal deficits in depression vulnerability. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 33(3), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-0089202-1 Kemeny, M., Foltz, C., Cavanagh, J., Cullen, M., Giese-Davis, P., Jennings, P., & Ekman, P. (2012). Contemplative/emotion training reduces negative emotional behavior and promotes prosocial responses. Emotion, 12(2), 1–338. Kirby, J., Day, J., & Sagar,, V. (2019). The “flow” of compassion: A meta-analysis of the fears of compassion scales and psychological functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.03.001 Kirby, J., Tellegen, C., & Steindl, S. (2017). A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current State of knowledge and future Directions. Behavior Therapy, 48. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003 Laithwaite, H., O’Hanlon, M., Collins, P., Doyle, P., Abraham, L., Porter, S., & Gumley, A. (2009). Recovery after psychosis (RAP): A compassion focused programme for individuals residing in high security settings. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37(05), 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S1352465809990233 Lambert, M., & Ogles, B. (2004). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5, 139–193. Leaviss, J., & Uttley, L. (2015). Psychotherapeutic benefits of compassion-focused therapy: An early systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 45(5), 927–945. https://doi.org/10. 1017/S0033291714002141 Lucre, K. M., & Corten, N. (2013). An exploration of group compassion-focused therapy for personality disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 86(4), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.2012.02068 MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion & psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 545–552. Marshall, M., Zuroff, D., McBride, C., & Bagby, R. (2008). Self criticism predicts differential response to treatment for major depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(3), 231–244. Matos, M., Duarte, C., Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Petrocchi, N., Basran, J., & Gilbert, P. (2017). Psychological and physiological effects of compassionate mind training: A randomized controlled study. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1699–1712. https://doi. org/10.1007/s12671-017-0745-7. Mayhew, S. L., & Gilbert, P. (2008). Compassionate mind training with people who hear malevolent voices: A case series report. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 15(2), 113–138. https:// doi.org/10.1002/cpp.566 McManus, J., Tsivos, Z., Woodward, S., Fraser, J., & Hartwell, R. (2018). Compassion focused therapy groups: Evidence from Psychotherapy Research routine clinical practice. Behaviour Change, 35(3), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2018.16 Naismith, I., Ripoll, K., & Pardo, V. (2020). Group compassionbased therapy for female survivors of intimate-partner violence and gender-based violence: A pilot study. Journal of Family Violence, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-019-00127-2 Neff, K., & Germer, C. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44. Pace, T., Negi, L., Adame, D., Cole, S., Sivilli, T., Brown, T., & Raison, C. (2009). Effect of compassion meditation on neuroendocrine, innate immune and behavioral responses to psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(1), 87–98. Pedersen, T., & Smart, D. (2007, August). An empirical model of development for distressed college students [Poster presentation]. Annual convention of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco. Pinto-Gouveia, J., Matos, M., Castilho, P., & Xavier, A. (2014). Differences between depression and paranoia: The role of emotional memories, shame and subordination. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 21(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10. 1002/cpp.1818 Porges, S. W. (2017). The pocket guide to the polyvagal theory: The transformative power of feeling safe. WW Norton & Co. 13 Ribeiro, M., Fross, J., & Turner, M. (2017). The college Counselor’s guide to group Psychotherapy. Taylor and Franscis. Santor, D., Zuroff, D., & Fielding, A. (1997). Analysis and revision of the depressive experiences questionnaire: examining scale performance as a function of scale length. Journal of Personality Assessment, 69(1), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1207/ s15327752jpa6901_8 Sommers-Spijkerman, M., Trompetter, H., Schreurs, K., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2018). Compassion-focused therapy as guided self-help for enhancing public mental health: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(2), 101. https://doi.org/10.1037/ ccp0000268 Tangney, J., & Dearing, R. (2002). Shame and guilt. Guilford Press. Tangney, J., Dearing, R., Wagner, P., & Gramzow, R. (2000). The test of self- conscious affect-3 (TOSCA-3). George Mason University. Vimalakanthan, K., Kelly, A., & Trac, S. (2018). From competition to compassion: A caregiving approach to intervening with appearance comparisons. Body Image, 25, 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.03.003 Yarnell, L., & Neff, K. (2013). Self-compassion, interpersonal conflict resolutions, and wellbeing. Self and Identity, 12, 146– 159.