Contract Law: Doctrine of Consideration - Casebook Excerpt

advertisement

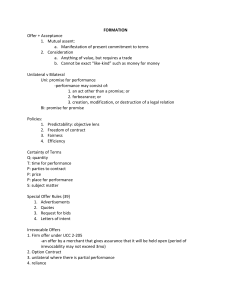

Part I:The Doctrine Of Consideration A. Donative Promises, Form, and Reliance a. Simple Donative Promises i. Dougherty v Salt 1. Boy given promissory note at aunt’s death without any exchange. No consideration to support promise, a promise to make a gift is not enforceable. Restatement Second 17 1. Except as stated in Subsection 2. the formation of a contract requires a bargain in which there is a manifestation of mutual assent to the exchange and a consideration. Restatement Second 71 1. To constitute consideration, a performance or a return promise must be bargained for. 2. A performance or return promise is bargained for if it is sought by the promisor in exchange for his promise and is given by the promisee in exchange for that promise. 3. The performance may consist of (a) an act other than a promise, (b) a forbearance, or (c) the creation, modification, or destruction of a legal relation. b. The Element of Form i. Schnell v Nell 1. A husband agreed to pay $200 to wife’s relatives at her death when her estate was 0. A signed sealed document to give money is not enforceable as the reasons for that promise do no constitute consideration. c. The Element of Reliance i. Kirksey v Kirksey 1. Defendant moved to brother in laws land in promise of housing and farm. The promise was not enforceable because it was gracious. 2. Remember promissory estopple can make this kind of promise enforceable now. Restatement Second 90 1) A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person, and which does induce such action or forbearance, is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcing the promise.[The remedy granted for breach may be limited as justice requires.] Restatement Second 90 1) a promise 2) which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person 3) which does induce such action or forbearance 4) is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcing the promise. Restatement Second 71 1. To constitute consideration, a performance or a return promise must be bargained for. 1 2. A performance or return promise is bargained for if it is sought by the promisor in exchange for his promise and is given by the promisee in exchange for that promise. Exceptions to consideration o Guaranty and option contracts o Promissory estopple o Past consideration ii. Feinberg v Pfeiffer Co. 1. Company promised employee to give her 200 a month whenever she retired. Promise Is enforceable as he relied on the promise. Enforceable under the doctrine of promissory estopple. 2. Hayes v Plantation Steel Restatement Second 90 1. a promise 2. which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person 3. which does induce such action or forbearance 4. is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcing the promise. a. Kirksey v Kirksey Related Doctrines o Deceit (also called fraud)—a tort doctrine o Representation of fact is made with intent to deceive someone o Made with intent to induce reliance, and does induce reliance o Result: Injured party may recover actual damages caused by the reliance and punitive damages o Equitable estoppel (also called estoppel “in pais”)—a broad, general legal doctrine— not limited to contract situations o Representation of some fact is made (without intent to deceive) o There is foreseeable reliance on the representation by another person o Result: Person who made the representation is estopped (prevented) from contradicting or denying the fact as it was represented o Promissory estoppel—a contract doctrine o Promise is made; promisor seeks nothing in exchange but the promisee’s reliance on the promise is foreseeable o Promisee does rely on the promise to his detriment o Result: Promisee may enforce promise as justice requires o Bargained-for consideration—a contract doctrine o Promise is made; promisor seeks a return promise or performance in exchange for his promise o Promisee makes the return promise or performance in exchange o Result: Promisee may enforce promise according to its terms d. Past Consideration i. Traditional exceptions to past consideration ii. Mills v Wyman 2 1. An adult son became sick, and his father wrote a promising note to reimburse the person caring for him. The promise for incurred expenses was unenforceable because it lacked consideration and was gracious. There was a moral obligation, but nothing was given in exchange for the promise. iii. Webb v McGowin iv. McGowin agreed to pay Webb 15 a month every two weeks for the rest of his life for an injury caused by him. the promise is enforceable as it caused serious injuries and saved promisor from serous injurie or even death. Restatement Second 86 1. A promise made in recognition of a benefit previously received by the promisor from the promisee is binding to the extent necessary to prevent injustice. 2. A promise is not binding [under this section] a. If the promisee conferred the benefit as a gift or for other reasons the promisor has not been unjustly enriched; or b. To the extent that its value is disproportionate to the benefit. B. The Bargain Principle and Its Limits Limits to Bargain Principle Not all promises are enforceable, even if bargained for: o Statute of frauds o Unfair or one-sided bargains Duress Unconscionability o Illusory contracts o Legal duty rule o Contracts against public policy a. The Bargain Principle i. Hamer v Sidway Oral promise from uncle to never drink or gamble for six yeats. Is it enforceable? Yes because there was a bargain nephew did not drink or gamble for 6yrs to receive the money uncle promised. Example of unilateral contract. Restatement Second 71 1. To constitute consideration, a performance or a return promise must be bargained for. 3 2. A performance or return promise is bargained for if it is sought by the promisor in exchange for his promise and is given by the promisee in exchange for that promise. 3. The performance may consist of (a) an act other than a promise, (b) a forbearance, or (c) the creation, modification, or destruction of a legal relation. Restatement Second 90 1. a promise 2. which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person 3. which does induce such action or forbearance 4. is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcing the promise. ii. Statute of Frauds 1. Contracts have to be in writing or would otherwise be unenforceable 2. Promise by administrator of estate o pay debts of the deceased with his/her own funds 3. Guaranty contracts (surety contracts) 4. Promise made “in consideration of marriage” 5. Transfer of interest in land 6. Promise not to be performed within 1 year 7. Sale of goods for $500 or more (UCC) iii. Hancock Bank & Trust Co. v Shell Oil Co. 1. Shell had a lease for 15 yrs at et price, after change in management suit was brought to terminate bad lease. Contract was enforceable even if it may seem a bad bargain. There was consideration in the contract. iv. Batsakins v Demotsis 1. There was a loan between the two parties for Greek drachma of about 25 in exchange for 2000. Is the agreement enforceable, yes because there was a promise made to pay that money plus interest. Inadequacy of consideration will not invalidate a contract. b. Duress i. Totem Marine Tug & Barge, Inc, v Alyeska Pipeline Service Company Contract to deliver pipelines from TX to Alaska had delays and contract was canceled. Payments were also delayed. Was here duress? there was evidence of duress withholding payment in bad faith can be considered a wrongful threat. Restatement Second 175 4 1. If a party's manifestation of assent is induced by an [A] improper threat by the other party [B] that leaves the victim no reasonable alternative, the contract is voidable by the victim. ii. Improper threat Restatement Second 176 1. A threat is improper if: a. what is threatened is a crime or a tort, or the threat itself would be a crime or a tort if it resulted in obtaining property, OR b. what is threatened is a criminal prosecution, OR c. what is threatened is the use of civil process and the threat is made in bad faith, OR d. the threat is a breach of the duty of good faith and fair dealing under a contract with the recipient 2. A threat is improper if the resulting exchange is not on fair terms, AND a. the threatened act would harm the recipient and would not significantly benefit the party making the threat, OR b. the effectiveness of the threat inducing the manifestation of assent is significantly increased by prior unfair dealing by the party making the threat, OR c. what is threatened is otherwise a use of power for illegitimate ends Bargain principle and its limits d. Unconscionability i. Williams v Walker-Thomas Furniture Co 1. Furniture store leased all furniture at pro-rata meaning items would not be paid in full until all debt was paid. Was there unconscionability and did it apply? Unconscionability = absence of meaningful choice and terms unreasonably favor the other party evidence of both were present. ii. Restatement contracts second 208 If a contract or term thereof is unconscionable at the time the contract is made a court may refuse to enforce the contract or may enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconscionable term or may so limit the application of any unconscionable term as to avoid any unconscionable result. iii. UCC 2-302 1. If the court as a matter of law finds the contract or any clause of the contract to have been unconscionable at the time it was made the court may refuse to enforce the contract, or it may enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconscionable clause, or it may so limit the application of any unconscionable clause as to avoid any unconscionable result. 2. When it is claimed or appears to the court that the contract or any clause thereof may be unconscionable the parties shall be 5 afforded a reasonable opportunity to present evidence as to its commercial setting, purpose and effect to aid the court in making the determination. Duress? Restatement Second 175 1) If a party's manifestation of assent is induced by an [A] improper threat by the other party [B] that leaves the victim no reasonable alternative, the contract is voidable by the victim. iv. Maxwell v Fidelity Financial Services Inc 1. A door-to-door salesman sells a water heater to the Maxwells worth 6,000 with 19.5 interest rate. They paid for a couple of years and later sought declaratory judgment because the contract was unconscionable and not enforceable. There was sufficient evidence of unconscionability which is part of the UCC 2-302. v. UCC 2-302 vi. Restatement (Second) 71 e. Illusory promise i. What looks like a bargain but turns out not to be one? 1. If one party is not obligated to do anything, the contract is unenforceable ii. Scott v Moragues Lumber Co. 1. Lumber company and Scott agreed that if Scott acquired a certain vessel, they would charter it to carry cargo. Was there consideration when Scott had no obligation o purchase the vessel? Yes, because once the purchase was made the contract became enforceable. A contract can be conditioned on the happening of an event. iii. Wood v Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon 1. Lucy agreed to give Wood exclusive right to place endorsements. Was there consideration when there is not an expressed obligation to obtain endorsements? Yes there was consideration. Contractual obligations can be expressed or implied. iv. UCC 2-306 (2) 2) A lawful agreement by either the seller or the buyer for exclusive dealing in the kind of goods concerned imposes unless otherwise agreed an obligation by the seller to use best efforts to supply the goods and by the buyer to use best efforts to promote their sale v. Office pavilion S Florida, Inc. v Asal Prods., Inc. 1. ASAL negotiated a contract with Office Pavilion which was later amend to include the sale chairs. The parties agreed that the terms and conditions of the keyboard contract would govern the sale of the chairs, except for the delivery and quantity terms. The agreement did not require ASAL to make any purchases of chairs. 6 ASAL sued Office Pavilion for its lost potential profits on the sale of those chairs. Was the contract enforceable? No because there was no consideration in exchange for office pavilions promise to deliver chars. Office pavilion agreed to fill orders by ASAL, but ASAL had no obligation to place orders. vi. UCC 2-201 [A] contract for the sale of goods for the price of $500 or more is not enforceable by way of action or defense unless there is some writing sufficient to indicate that a contract for sale has been made between the parties and signed by the party against whom enforcement is sought or by his authorized agent or broker. A writing is not insufficient because it omits or incorrectly states a term agreed upon but the contract is not enforceable under this paragraph beyond the quantity of goods shown in such writing. vii. 2-306 (1) 1) A term which measures the quantity by the output of the seller or the requirements of the buyer means such actual output or requirements as may occur in good faith, except that no quantity unreasonably disproportionate to any stated estimate or in the absence of a stated estimate to any normal or otherwise comparable prior output or requirements may be tendered or demanded. viii. Restatement Second 71 f. Legal Duty i. Gray v Martino 1. Police officer in Atlantic city recovered diamonds that defendant agreed to pay 500 to whoever found them. Defendant refused to pay as police officer helped solve the case. Can he claim the reward? No because if he was required to recover diamonds as part of official duties, he cannot claim reward. Legal duty rule, he was just doing his job. ii. Lingenfelder v Wainwright Brewery Co. 1. Jungenfled had a contract to build a brewery but said he would not complete it unless he got the refrigeration contract, and he was promised instead 5% of the contract. Brewery did not fulfill. Was Jungenfled entitled to the 5%? There is no consideration at time of promise, legal duty rule. iii. Foakes v Beer 1. Dr. Foakes owed Julia Beer and they agreed Foakes would pay 500 upfront and 1550 very 6months till debt was paid, Beer said she would waive interest and later sued Foakes for interest. Was there consideration? No an agreement to pay lesser sum than owed is not consideration. It would be different if at time of new arrangement Foakes offered something in exchange. iv. Angel v Murry 1. There was a contract to pick up trash but after an increase in dwelling unity there was an additional cost asked to be covered and they did. Citizen sued for the increase in payment saying it 7 was illegal. Was there was a duty rule? Parties contract voluntarily modified it due to unanticipated circumstances, new contract is enforceable. 2. Restatement 89 (1) the parties voluntarily agree and if (2) the modification was made before the contract was fully performed; (3) the circumstances which prompted the modification were unanticipated by the parties and (4) the modification is on fair and equitable terms. UCC 2-209 Modification needs no consideration to be binding (CISG is the same) Official Comment: modification must be sought in good faith Restatement Second 281 Need an existing dispute “Accord”: an agreement to compromise or settle the dispute “Satisfaction”: performance of the accord Effects: The accord suspends the original obligation Performance of the accord discharges the original obligation If the accord is not performed, the original obligation is revived; and suit can be brought on original obligation or the accord Compare “substituted contract”: immediately replaces original obligation with the new one (novation); original obligation is now gone v. McMahon Food Corp. v Burger Dairy UCC 3-311 Need a bona fide dispute about what is owed (3-311(a)) Check must be tendered in good faith (3-311(a)) Need conspicuous “full payment” message on or with check (3-311(b)) The claim/dispute is settled if the check is cashed knowing that it was tendered in full payment (accord and satisfaction) (3-311(d)) The claim is settled even if check is cashed not knowing that it was tendered in full payment, unless: o An organization notified the payor about a special address and the check was not sent to that address, or o The check recipient refunds the $ to the payor within 90 days (option not available to organization that has created a special address) (3-311(c)) 3. The Limits of Contract: Contracts and Public Policy a. Restatement 178 Restatement 178 8 1. A promise or other term of an agreement is unenforceable on grounds of public policy if legislation provides that it is unenforceable OR the interest in its enforcement is clearly outweighed in the circumstances by a public policy against the enforcement of such terms. 2. In weighing the interest in the enforcement of a term, account is taken of a. the parties' justified expectations, b. any forfeiture that would result if enforcement were denied, and c. any special public interest in the enforcement of the particular term. 3. In weighing a public policy against enforcement of a term, account is taken of a. the strength of that policy as manifested by legislation or judicial decisions, b. the likelihood that a refusal to enforce the term will further that policy, c. the seriousness of any misconduct involved and the extent to which it was deliberate, and d. the directness of the connection between that misconduct and the term b. Balfour v Balfour c. Perry v Atkinson i. Atkinson promised Perry that is she got an abortion he would later impregnate her but he did not fulfill his promise. Is this an action of fraud? No because this is a promise made by consenting adults regarding their relationship that the court did not have say over. d. In re Marriage of Witten i. Tamera and Trip had frozen fertilized eggs refrigerated and when they got a divorce the question of who kept the embryos started which needed mutual consent on how to dispose of them. The agreement for public policy reasons con only be used or disposed by mutual consent. Part II. Remedies for Breach of Contract A. An Introduction to Contract Damages a. Hawkins v McGee i. McGee did a skin graft where he promised that his hand would be 100% perfect/good but the result was that the hand was hairy and in great pain. was there a contract? How do you measure damages? A contract was formed. The measure of damages is the difference between the value of a good or perfect hand and the value of the hand at a present condition. 9 Restatement Second Contracts 344 Judicial remedies under the rules stated in this Restatement serve to protect one or more of the following interests of a promisee: (a) his "expectation interest," which is his interest in having the benefit of his bargain by being put in as good a position as he would have been in had the contract been performed,–Compare “B” to “C” in previous slide (b) his "reliance interest," which is his interest in being reimbursed for loss caused by reliance on the contract by being put in as good a position as he would have been in had the contract not been made,–Compare “B” to “A” in previous slide or (c) his "restitution interest," which is his interest in having restored to him any benefit that he has conferred on the other party. [to be discussed later] B. The Expectation Measure a. Damages For Breach of a Contract to Perform Services i. Louise Caroline Nursing Home 1. Nursing home sought damaged for breach of contract of an unfinished job. Another contractor finished the work. What was the correct measure of damages? The cost of completion. There was no compensation as the substitute contractor completed the job for less than the original contract. ii. Peevyhouse 1. The Peevyhouse leased their farm to a coal mining company with a provision that the coal mining was to complete physical restoration. The coal company did not comply and argued that the value of the land if the work would be done would be 300 more and cost of repair would be 29,000. If the cost of performing exceeds the added value what is the correct measure of damages? The diminished value of land is the proper measure of damages, cost of performance would be an economic waste. iii. Buyer’s damages when Seller breaches UCC 2-711 (1) Where seller fails to make delivery or repudiates or the buyer rightfully rejects or justifiably revoked acceptance then with respect to any goods involved, and with respect to the whole of the breach goes to the whole contract the buyer may cancel and whether or not he has done so may in addition to recovering so much of the price as has been paid. UCC 2-712 Difference between contract price and cover price (if buyer “covered” in good faith and without unreasonable delay) UCC 2-713 Difference between contract price and market price at date of breach (if buyer did not cover) UCC 2-714 Difference between value of goods as accepted and value as warranted 10 UCC 2-715 (1) Incidental damages resulting from seller’s breach include expenses reasonably incurred in inspection, receipt, transportation and care and custody of goods rightfully rejected any commercially reasonable charges, expenses or commissions in connection with effecting cover and any other reasonable expense incident to the delay or other breach. iv. Sand & Gravel v. Egerer v CSR West 1. Egerer required a substantial amount of land fill to develop some property he owned. CSR West was doing road construction for the Department of Transportation (DOT) and expected to have a lot of excavated shoulder material to dispose of. In May 1997, Egerer contracted with CSR West to purchase all the shoulder excavation material from that road project at the rate of $.50 per cubic yard. CSR West performed a small part of the contract, but the DOT then changed its rules and said CSR West could use shoulder excavation material in the road project itself. In July 1997 CSR West decided to do that instead of selling it to Egerer. Egerer did not cover (buy replacement fill) at that time because it was very expensive and he did not think he could get it to his property by the end of the summer. Several months later, in January/February 1998, he obtained price quotes for replacement fill ("pit run", which is a higher quality fill material) ranging from $8.25 to $9.00 per cubic yard, but the prices exceeded his budget so he did not purchase at that time either. More than a year after that, in the summer of 1999, Egerer purchased fill material resulting from an unexpected landslide at a cost of $6.39 per yard. Two years before the contract with CSR West was made, in 1995, Egerer had purchased fill material from another road excavation project at $1.10 per yard. Egerer sued CSR West and the trial court awarded damages as the difference between the contract price ($.50/yard) and the market price of $8.25/yard for every yard of shoulder excavation that CSR West used on the DOT road project instead of selling it to Egerer, for a total of $129,812. 2. Issue: What is the proper measure of damages for breach by a seller to sell fill material when the buyer does not cover for more than two years after the breach, and the evidence of the market price for fill material is for a higher quality product at a time six months after the breach? 3. Holding: The proper measure of damages under UCC 2-713 is the difference between the contract price and the market price for the higher quality material six months after the breach. Damages for breach by person receiving the services Contract price – less costs saved – less payments made = total damages 11 Alternative Reimburse for costs spent so far + add the builders expected profits – deduct payments made = damages b. Damages For Breach of a Contract for the Sale of Goods i. HWH Cattle Co. v Schroeder 1. H-W-H Cattle contracted to buy 2,000 steer from Schroeder for $67 per hundredweight ($.67 per pound). In turn, HWH contracted to sell the same cattle to Western Trio for $67.35 per hundredweight, making a slight profit on each steer. HWH paid Schroeder a $50,000 down payment ($25 per steer). Schroeder delivered only 1,397 steers, breaching the contract to deliver the other 603. HWH sued Schroeder for breach of contract. The district court awarded HWH a pro rata portion the down payment it had made to Schroeder (603 x 25 = $15,075) and damages for HWH’s lost $0.35 profit per hundredweight of undelivered steer (603 x .0035 x 650lb avg. steer weight(?) = 1,371.83). HWH appealed, seeking a measure of damages under UCC § 2-713, the difference between the contract price of $67 per hundredweight and the market price at the time of the breach. (We don't know for sure what the market price was on the day of the breach, but HWH must have thought it was higher than $67 per hundredweight). The buyer is limited to the lost expected profits on resale. Buyer should be left as if contract was performed. ii. Kearsarge Computer v Acme Staple Co. 1. Kearsarge and Acme signed a one-year contract under which Kearsarge would provide data-processing services to Acme. Seven months into the contract, Acme terminated the contract due to Kearsarge’s unsatisfactory performance. By this point, Acme had spent $837.75 fixing Kearsarge’s errors. After the termination, Kearsarge got its employees to take voluntary pay cuts to stay afloat, and it secured some new business. Kearsarge sued Acme for breach of contract. The trial court (for some reason) found in favor of Kearsarge and awarded it $12,313.22, the full balance of the contract price. Acme appealed. The service provider is entitled to the full remaining contract balance if the early termination did not result in any significant cost savings and the new business could have been secured regardless of the breach. iii. Seller’s damages when Buyer breaches UCC 2-706 Difference between the contract price and the resale price (similar to “cover”) UCC 2-708 (1) Difference between the contract price and the market price at the time of breach (if no resale) UCC 2-708 (2) 12 If other measures are inadequate to put Seller in same position as full performance, damages are the lost profits on the sale. UCC 2-718 At a minimum, Seller may retain 20% of Buyer’s payments, but only up to $500 maximum UCC 2-710 1. Neri v Retail Marine Corp. a. Facts: Neri contracted to purchase a boat from Retail Marine Corp. (RMC). Neri paid a deposit. Neri was facing health problems and cancelled the contract. RMC ultimately sold the boat to someone else for the same price. RMC refused to refund Neri’s deposit. b. Issue: What are damages? c. Holding: If the boat dealer would have made two sales instead of one, the proper measure of damages is the lost expected profits on the contract that was breached, plus incidental damages. If that total is less than the buyer's deposit, the dealer must refund the remainder to the buyer. d. Reasoning: under 2-708(2), when the other measures of damages do not put the seller in the same position it would have had if the buyer not breached, the damages are the seller's lost profits, plus incidentals. In this case, the seller would have sold two boats and got two profits if Neri had not breached. Mitigation Restatement 350: [D]amages are not recoverable for loss that the injured party could have avoided without undue risk, burden or humiliation. . . The injured party [can recover damages if ] he has made reasonable but unsuccessful efforts to avoid loss. 2. Shirley MacLaine Parker v. 20th Century Fox a. Facts: Shirley MacLaine entered a contract with Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corp. in which she was to play the female lead in the musical film “Bloomer Girl,” and she would be paid $750,000. Fox decided not to produce the film and offered MacLaine the female lead in another for the same compensation. MacLaine did not accept the offer and brought suit to recover the full $750,000 under the original contract. b. Issue: Damages? c. Holding: When the substitute film offer is different or inferior to the role in the original contract, damages should not be reduced when the actor refuses the offered role. d. Reasoning: The general rule for breach by an employer is that the employee's damages are the amount of salary provided for in the contract, reduced by the amount that the employer proves the employee has actually earned or with reasonable effort might have earned from other work after the breach. If the employee turns down substitute work, the amount that could have been earned in that job will reduce damages only if the substitute job was 13 substantially similar to the original contract work. Where the substitute work is different or inferior, damages will not be reduce if the employee refuses to accept the job. Foreseeability 3. Hadley v. Baxendale a. Facts: Hadley owned and operated a grain mill. The crank shaft that operated the mill broke and halted mill operations. Hadley went to Baxendale's shipping business to get the shaft shipped for repair or replacement. Hadley's representative told Baxendale's clerk that the mill was stopped and the shaft had to be sent immediately. The clerk said the shaft would be delivered the day after they received it if they got it before noon. The shaft was delivered to the shipper before noon and a fee was paid, but the shaft was not delivered to its destination for several days. Hadley sued Baxendale for lost profits due to the delay in getting the new shaft b. Issue: Is Baxendale liable to Hadley for lost profits because it breached its contract to deliver the broken mill shaft to its destination on the day after receipt? c. Holding: No. d. Reasoning: Damages can be recovered for certain consequences resulting from breach of contract. The rule is that recovery may be had for damages that are fairly and reasonably considered either (1) arising naturally from the breach or (2) were reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties, at the time they made the contract, as the probable result of the breach. Hadley v Baxendale rule (1) “such as may fairly and reasonably be considered either arising naturally. . . from the breach. . . or (2) such as may reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties, at the time they made the contract, as the probable result of the breach Restatement 351 (1) Damages are not recoverable for loss that the party in breach did not have reason to foresee as a probable result of the breach when the contract was made. (2) Loss may be foreseeable as a probable result of a breach because it follows from the breach (a) in the ordinary course of events, or (b) as a result of special circumstances, beyond the ordinary course of events, that the party in breach had reason to know. (3) A court may limit damages for foreseeable loss by excluding recovery for loss of profits, by allowing recovery only for loss incurred in reliance, or otherwise if it concludes that in the circumstances justice so requires in order to avoid disproportionate compensation. Consequentials under the UCC 14 2-715(2): Consequential damages resulting from the seller’s breach include A) any loss resulting from general or particular requirements and needs of which the seller at the time of contracting had reason to know and which could not reasonably be prevented by cover or otherwise; and B) injury to person or property proximately resulting from any breach of warranty. Certainty 4. Kenford Co. v. Erie County a. Facts: Erie County (Buffalo, NY) wanted to build a domed stadium to hold sporting and entertainment events. (At the time, there was only one such stadium in the country--the Houston Astrodome.) The county agreed that Dome Stadium, Inc. (DSI) would be granted a 40 year lease to operate the stadium after it was built. If a mutually acceptable lease could not be agreed upon, DSI would be granted a management contract to operate the stadium for 20 years. The county later decided not to build the stadium and terminated the DSI contract. DSI brought a breach of contract action and sought damages for the lost profits expected during the 20 year management contract. At trial, a jury awarded DSI a multi-million dollar damage award. The county appealed. b. Issue: When a county grants a business a 20 year contract to manage a domed stadium and then breaches the contract, is the county liable for the lost profits that the business would have earned by managing the stadium during that 20 year period? c. Holding: No. Profits over the 20 year period are too speculative under these circumstances and cannot be awarded as damages. d. Reasoning: Damages must be proven with "reasonable certainty." Damages may not be speculative but must be reasonably certain and directly traceable to the breach. In this case, the profits that DSI would have earned by managing the stadium over the 20 year period were too speculative. DSI had never operated such a business before. In fact, there was only one other domed stadium in the country at the time, so there is not much objective evidence to support a claim for lost profits in managing domed stadiums. Moreover, there are too many variables and uncertainties in the sports/entertainment business to establish lost profits with any degree of confidence. Damages for mental distress 5. Valentine v. General American Credit a. Facts: Valentine was employed under a contract that permitted termination only for "cause." She was terminated without cause and she sought damages for, among other things, emotional distress resulting from the wrongful termination and punitive (exemplary) damages. The trial court dismissed her claims for those two types of damage awards. She appealed. b. Issue: Are damages for emotional distress available? 15 c. Holding: No. d. Reasoning: Damages for emotional distress are generally not awarded for breach of contract. Damages can be determined with reasonable certainty for the employee's economic losses but not for emotional distress. Restatement (Second) Contracts 353: Not allowed unless: [1] Breach caused bodily harm, or [2] The contract or breach is of such a kind that serious emotional disturbance was a particular likely result [cf. Hadley v. Baxendale rule] Liquidated damages Parties decide in advance what the remedy for breach will be Restatement (Second) Contracts 356: the provision will be enforced “only at an amount that is reasonable in the light of [1] the anticipated or actual loss caused by the breach and [2] the difficulties of proof of loss.” UCC 2-718(1): allowed “only at an amount which is reasonable in the light of [1] the anticipated or actual harm caused by the breach, [2] the difficulties of proof of loss, and [3] the inconvenience or nonfeasibility of otherwise obtaining an adequate remedy.” 6. NPS, LLC v. Minihane a. Facts: Minihane signed a contract to purchase football tickets for all of the evil New England Patriots' football games for a ten year period. The agreement provided that if at any point he breached by not buying tickets, his ticket obligations for the remaining term of the contract would be "accelerated" (immediately due and payable), and the stadium developer would not have to mitigate damages by trying to resell them so someone else. Minihane breached after one year. The developer sought to enforce the agreement and make him pay for all of the tickets for the remaining nine years. b. Issue: Is the purchaser liable for the entire ten year cost of tickets if he breaches after one year and the contract says that he is liable for the entire amount? c. Holding: Yes. This is a valid liquidated damages provision that the parties agreed to and it will be enforced according to its terms. Specific performance Court orders the breaching party to perform the contract terms First, money damages must be an inadequate remedy Second, court will exercise its equitable discretion to determine whether SP is appropriate 16 7. London Bucket a. Facts: London Bucket Co. agreed to install a heating system. The work was not successfully completed, and the hotel sued for an order instructing the company to complete the contract according to its terms. b. Issue: Is specific performance of the contract an appropriate remedy? c. Holding: No. In a construction contract such as this, the appropriate remedy is money damages. Specific performance will only be awarded when money damages are not an adequate and complete remedy. Restatement 360 Sale of Goods UCC Buyer—2-716 (action for the goods): “Unique” goods or “other proper circumstances” (e.g., buyer unable to cover) Seller—2-709 (action for the price): o Accepted goods o Destroyed goods (if ROL on buyer) o Goods cannot be resold (e.g., goods custom-made for buyer) 8. Walgreen Co. v. Sara Creek a. Facts: Walgreen signed a 30 year lease with Sara. Sara owned the mall. Sara would not lease space in the mall to any other company that operated a pharmacy. With about 10 years remaining on the contract, Sara was about to rent space in the mall to Phar-Mor, which does operate pharmacies. b. Issue: Is the provision enforceable by an injunction? c. Holding: The lease provision is enforceable by an injunction that prohibits the lessor from renting to a tenant who will operate a competing pharmacy with the lessee. The choice between remedies requires a balancing of the costs and benefits of each remedy. The most efficient remedy is the most appropriate. Reliance Damages Restatement (Second) Contracts 344 (b) his "reliance interest," which is his interest in being reimbursed for loss caused by reliance on the contract by being put in as good a position as he would have been in had the contract not been made, or 9. Security Stove a. Facts: Plaintiff manufactures gas and oil furnaces. The plaintiff contracted with defendant to ship all of the furnace parts to Atlantic city by October 8th. Defendant failed to deliver one of the most important parts of the furnace from to Atlantic City on time. Consequently, the furnace could not be exhibited and demonstrated as planned. b. Issue: Was the plaintiff entitled to reimbursement of the expenses it had paid relying on the shipping contract? 17 c. Holding: Yes. The shipping company was aware that if the parts did not arrive on time the expenses plaintiff incurred on the trip would likely be wasted. It would be difficult to prove any lost profits if the convention had gone as planned, plaintiff will have no remedy if it cannot recover its reliance costs. Restitution measure Restatement (Second) Contracts 344 (c) his "restitution interest," which is his interest in having restored to him any benefit that he has conferred on the other party. Restatement (Second) Contracts 371 *(a) the reasonable value to the other party . . . in terms of what it would have cost him to obtain it from a person in the claimant’s position, or (b) the extent to which the other party’s property has been increased in value or his other interests advanced 10. Osteen v. Johnson a. Facts: The Osteens paid defendant $2500 in exchange for defendant promoting the plaintiffs daughter in her country music career for one year. Specifically, defendant agreed to arrange for Linda to record two records. One of the records would be sent to DJs around the country. If that record met with any success, the defendant would do the same for the second record. The first record did meet with some success, but the defendant did not promote the second record. b. Issue: Were the plaintiffs entitled to restitution of the $2500 they paid the promoter? c. Holding: Yes, restitution damages were appropriate, but the $2500 payment will be offset by the reasonable value of the services the defendant did provide before the contract was terminated. 11. Algernon Blair a. Facts: Algernon Blair entered a contract with the United States for the construction of a naval hospital. Blair subcontracted with Coastal Steel for steel erection on the project. Coastal Steel asked Blair to pay for crane rental, but Blair refused. Coastal Steel stopped performing after it had completed about 28% of the contract. Coastal filed suit against Blair for the value of labor and equipment already furnished before it stopped working. At the time of the breach, Coastal Steel was to be paid only $37,000 more on the contract, but it would have cost Coastal Steel more than $37,000 to finish the job had the breach not occurred. b. Issue: May a subcontractor, who justifiably ceases work under a contract because of the prime contractor’s breach, recover in quantum meruit the value of labor and equipment already furnished pursuant to the contract 18 irrespective of whether he would have been entitled to recover in a suit on the contract? c. Holding: Yes, a subcontractor, who justifiably ceases work under a contract because of the prime contractor’s breach, may recover the value of labor and equipment already furnished pursuant to the contract irrespective of whether he would have been entitled to recover in a suit on the contract. Quantum meruit damages allow a promisee to recover the value of services provided to the defendant irrespective of whether it would have lost money on the contract. 1. Kutzin v. Pirnie (restitution of deposit when buyer breaches) a. Facts: The Kutzins had a contract to sell their house to the Pirnies for $365,000. The Pirnies made a down payment of $36,000. They breached the contract by refusing to go through with the sale. The contract contained no liquidated damages provision and did not say the deposit was nonrefundable. The Kutzins eventually sold the house six months later for $352,500. b. Issue: If a buyer breaches a contract to purchase a home after making a $36,000 deposit, can the seller keep the entire deposit if its actual damages are less than $36,000 and the contract has no liquidated damages provision or deposit forfeiture clause? c. Holding: The seller can retain only the amount to cover its actual damages and must return the remainder of the deposit to the buyer. Restatement (3d) Restitution 36 (restitution for party who breaches) Disgorgement Damages 2. U.S. Naval Institute v. Charter Comm. a. Facts: Tom Clancy assigned his copyright for the book to the United States Naval Institute (Naval). Naval entered into an agreement with Charter Communications and Berkley that granted Berkley an exclusive license to publish a paperback edition of the book “not sooner than October 1985.” Berkley shipped the books to bookstores early which allowed them to start selling on September 15. The district court awarded Naval $35,380 in damages, $7,760 in disgorged profits that Berkley made by selling the paperback during September, plus prejudgment interest on the damage award. Both parties appealed. b. Issue: Can damages for breach of contract include disgorgement of profits that were earned by the contract breacher as a result of its breach? c. Holding: No, damages for breach of contract are sufficient if they put the nonbreaching party in the same position it would have held if the contract had been performed. So long as that is accomplished, disgorgement of profits is not permitted. 3. Coppola Enterprises, Inc. v. Alfone a. Facts: Alfone contracted with Coppola to purchase a residential lot and single family home for $105,690.00. Due to construction delays, Coppola pushed back 19 the project completion date. When construction was completed, Coppola sent Alfone a letter saying closing had to be done quickly. Alfone requested additional time to finance the purchase but Coppola refused to give extra time. Coppola then sold the property to another party for $170,000. The trial court found that Coppola failed to exercise good faith by refusing to give Alfone a reasonable time to make financing arrangements after Coppola's construction delays. The court awarded Alfone $64,310 in damages, the profits that Coppola made on the sale of the home after its breach. b. Issue: When the seller breaches a contract to sell a home, and the seller then sells the home to another buyer for a higher price, can the original buyer receive damages in an amount equal to the profits that the seller made on the second contract? c. Holding: A seller in breach of a real estate contract must disgorge profits made by selling the property at a higher price. A seller will not be permitted to profit from its breach of a contract to sell real property to a buyer. Even if the seller acted in good faith, the profits must be paid over to the buyer. Efficient breach Damages are seldom the same as actual contract performance Transaction costs, delay (and litigation costs) are uncertain; and Beth has to prove her losses No reward for those who plan ahead (Beth) Without a breach, the machine could still end up with Cathy if Beth assigns (sells) her rights to Cathy Undermines predictability of contracting Interpretation 1. Lucy v. Zehmer (“Frolic and Banter”) a. Facts: Lucy had expressed interest in buying the Ferguson farm, which the Zehmer's owned, several times in the past. On this occasion, Lucy and the Zehmer's were drinking in a bar/restaurant and Lucy asked if the farm had been sold to anyone else. When Mr. Zehmer said they had not sold it, Lucy said "I bet you wouldn't take $50,000 for that place." They talked some more and then Lucy wrote, on the back of a guest check, the words “I do hereby agree to sell W.O. Lucy the Ferguson Farm for $50,000 complete." Since the farm was co-owned by Zehmer's wife, Lucy tore up that check and wrote on the back of another check, "We hereby agree to sell to W.O. Lucy the Ferguson Farm complete for $50,000, title satisfactory to buyer." Mr. Zehmer signed it, and Mrs. Zehmer also signed shortly thereafter. Lucy then offered Zehmer $5 but Zehmer refused the money. Zehmer got an attorney to examine the title, which was fine. Lucy contacted Zehmer to arrange for closing, and Zehmer said they had no deal. He and his wife were just having some fun in the bar and were not serious about the contract. 20 b. Issue: Is a contract to sell a farm enforceable when agreement is made at a bar and written on the back of a guest check, and signed by the owners of the farm, but the owners claim they were just joking around and were not serious? c. Holding: The agreement is binding even if the sellers were not serious because a reasonable person would have believed that the sellers were serious about making the contract. Several facts support the conclusion that a reasonable person would have thought the Zehmers were serious. Lucy had expressed interest in the farm before. The price for the farm was fair. Even though the agreement was written on the back of a guest check, Lucy wrote it up twice and both Mr. and Mrs. Zehmer signed it without making it clear that they were joking. 2. Raffles v. Wichelhaus a. Facts: Plaintiff and defendant agreed that plaintiff would sell 125 bales of Surat cotton to defendant to arrive on a ship named Peerless from Bombay to Liverpool. At the time the contract was made, the defendant was thinking about a ship named Peerless that was going to leave Bombay in October. The plaintiff was thinking about a ship named Peerless that was going to leave Bombay in December. Plaintiff had no goods on the October Peerless. When the December Peerless arrived in Liverpool, the defendant refused to pay for the cotton. Plaintiff sued defendant for breach of the purchase agreement. b. Issue: If, at the time a contract is made, there is a misunderstanding by the parties about which ship will be delivering the goods, and when they will be delivered, is the contract enforceable? c. Holding: No, if there is a mutual misunderstanding about a basic term in the contract, the contract is unenforceable. The contract did not specify which ship was to deliver the cotton. Apparently there were two different ships names Peerless. Because of this latent ambiguity, there was no consensus about a basic term of the agreement. Therefore, the agreement is not enforceable. Restatement (Second) 20(1) There is no manifestation of mutual assent to an exchange [i.e., no contract] if the parties attach materially different meanings to their manifestations and: (a) neither party knows or has reason to know the meaning attached by the other; or (b) each party knows or has reason to know the meaning attached by the other. Frigaliment If language is ambiguous, how do we determine what the contract means? “Whole contract” Pre-contract negotiations Trade usage Definitions outside the contract (US gov’t) 21 Market prices 1. Embry v. H-M Dry Goods Co. (“reason to know”) 2. Facts: Embry was employed by Hargadine but his contract was about to expire. He had a meeting with the company president at which the renewal of his contract was discussed. Embry and the president testified differently about what was said at that meeting. Embry thought he had a one-year renewal, but he was terminated two and a half months later. Embry sued the company for breach of the one-year renewal. 3. Issue: For a contract to be enforceable, must both parties subjectively intend to be bound or is it sufficient that one party so intended? 4. Holding: If a reasonable person would have concluded that the parties had reached an agreement, then the contract is binding even if one of the parties secretly did not so intend. Restatement (Second) Contracts 201 (1)Where the parties have attached the same meaning to a promise or agreement or a term thereof, it is interpreted in accordance with that meaning. [Sprucewood Invest. Corp, p. 390] (2) Where the parties have attached different meanings to a promise or agreement or a term thereof, it is interpreted in accordance with the meaning attached by one of them if at the time the agreement was made: (a)that party did not know of any different meaning attached by the other, and the other knew the meaning attached by the first party; or (b) that party had no reason to know of any different meaning attached by the other, and the other had reason to know the meaning attached by the first party. [Lucy v. Zehmer; Embry; maybe Frigaliment] 1. Spaulding v. Morse (“plain meaning”) a. Facts: Morse and his wife divorced. The divorce decree provided that the wife would have custody of the couple's son and that Morse was to make payments to a trustee for their son's “care, custody, maintenance and support.” The agreement required him to pay $1,200 per year until the son entered “into some college, university or higher institution of learning beyond the completion of the high school” and $2,200 per year for up to four years while the son was attending the institution of higher education. The son joined the Army after completing high school, and Morse stopped making payments. b. Issue: Should a contract provision that is clear and unambiguous be enforced according to its terms if doing so would be contrary to the main purpose of the agreement? c. Holding: No. Although contract terms are usually enforced according to the plain meaning of the language used, if doing so is contrary to the main purpose of the agreement the terms will not be enforced as written. 2. Beanstalk Group v. AM General (“plain meaning”) 22 a. Facts: AM General Corporation (AM) manufactured Hummer vehicles. AM entered into a representation agreement with Beanstalk under which Beanstalk would act as AM's sole nonemployee representative for negotiating trademark license agreements for the Hummer. The agreement defined a license agreement as “any agreement or arrangement, whether in the form of a license or otherwise, granting merchandising or other rights in the Property.” Any payments for license agreements negotiated by Beanstalk were to be tendered to Beanstalk, which would deduct a 35% commission and forward the balance to AM. Two years later, AM entered a joint-venture with General Motors (GM) under which GM essentially purchased the Hummer trademark. GM elected not to assume the representation contract that Beanstalk had with AM. Therefore, Beanstalk would no longer get commissions on licensing the Hummer trademark. Beanstalk demanded 35% of the consideration GM paid to AM for the Hummer trademark, considering it a "license agreement" as literally defined in the contract. b. Issue: Should a court apply the definition of "license agreement" in the agreement literally or should it apply the definition in a way that is consistent with the overall purpose of the contract? c. Holding: The court should apply the contract language in a way that is consistent with the purpose of the contract. In this case, the purpose of the representation agreement was to reward Beanstalk for going out and getting third parties to pay for using the Hummer trademark. For all practical purposes, AM no longer owns the trademark. GM does. Beanstalk did nothing to create the AM-GM joint venture. Despite Beanstalk's argument that the joint venture fits the literal definition of "license agreement" in the contract, it is clear that AM and Beanstalk did not intend it to cover a situation where AM transfers the Hummer trademark to someone else. When plain meaning not be used When there is no “plain meaning” (ambiguous language) When it’s inconsistent with the “purpose” of the contract When it leads to “absurd” results When it’s inconsistent with other contract language Offer and revocation Offer + Acceptance = Contract* O + A = K* What constitutes an offer? 1. Longergan v. Scolnick a. Facts: Defendant placed an ad in the newspaper offering property for sale. Defendant wrote plaintiff a letter describing the property, giving directions, and stating that his "rock bottom" price was $2,500. The letter also said "This is a form letter." Plaintiff wrote back stating that he was not sure he had found the property, asked for a legal description and suggested a certain bank as an escrow 23 agent should he decide to purchase. Defendant wrote a letter confirming that plaintiff had found the property and approved the bank as an escrow agent, but explained that plaintiff had to "decide fast, as I expect to have a buyer in the next week or so." Defendant sold the property to a third party four days later. Two days after that, plaintiff says he received defendant's letter. On the very next day, he wrote defendant agreeing to buy the land. When he learned that the property had been sold to someone else, plaintiff sued defendant for specific performance. b. Issue: Under the facts of this case, did defendant make an offer to sell the land? c. Holding: No. At no time did defendant make an offer to sell his land to plaintiff. The advertisement was a mere attempt to solicit offers from interested buyers. Thus, no offer was made to plaintiff, so there was nothing for plaintiff to "accept." Offer Restatement (Second) Contracts 24: “An offer is the manifestation of a willingness to enter into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it.” 2. Lefkowitz v. Great Minneapolis Surplus Store a. Facts: The Great Minneapolis Surplus Store published two advertisements in a newspaper for fur coats and stoles. One advertisement said “Saturday 9 A.M. Sharp 3 Brand New Fur Coats Worth to $100 First Come First Served $1 Each." A week later, another one said "1 Black Lapin Stole, Beautiful, worth $139.50 . . . $1.00 First Come First Served." Lefkowitz (a male) was the first to enter the store on both occasions and wanted to make the purchases as advertised. Both times the store refused to sell to him, citing a “house rule” that the promotion was only available to women. b. Issue: Whether the newspaper advertisement constituted an offer, and if so, whether Lefkowitz accepted. c. Holding: Yes, the newspaper advertisement constituted an offer, and Lefkowitz accepted by appearing at the store first in line. If an advertisement is “clear, definite, and explicit, and leaves nothing open for negotiation," it will be deemed an offer. Advertisements Not offers, over acceptance concern 3. Sateriale v. RJ Reynolds a. Facts: RJR ran a customer rewards program called Camel Cash. The program terms were presented on Camel Cash certificates, packages of Camel cigarettes, and in advertisements. The message was that customers who purchased Camel cigarettes and saved the certificates ("C-Notes") could exchange them for 24 merchandise under terms provided in a catalog showing the available merchandise. In October, RJR announced that the program would terminate in March of the following year. The announcement stated that customers could redeem their rewards before the program’s termination date in March. However, sometime in October RJR stopped printing catalogs and informed customers that it did not have any merchandise available for redemption. b. Issue: Whether the C-Notes, read in isolation or in combination with the catalogs, constituted an offer. c. Holding: Yes, viewed in light of all the circumstances, the C-Notes constituted a offer to form a unilateral contract with program participants. There was, however, an offer for a unilateral contract with each plaintiff--a promise (merchandise rewards) in exchange for plaintiffs' performance (purchasing Camel cigarettes and collecting C-Notes). Advertisements are not ordinarily viewed as offers, but courts have held that coupon programs such as this are unilateral offers. 4. Akers v. J.D. Sedberry, Inc a. Facts: Akers and Whitsett each had 5-year employment contracts with the Sedberry company. The two employees flew to company headquarters and met with Mrs. Sedberry. During a day-long meeting, the two employees offered their resignations effective in ninety days. They testified that Mrs. Sedberry pushed the offers aside and said she would not accept them. Mrs. Sedberry testified that she did not reject the offers but she did not accept them at the time because she wanted to contact the manager to discuss it with him. She did not, however, tell the employees that she was taking the matter under consideration. They continued their meeting without discussing the offer again. On the next working day (Monday), Mrs. Sedberry sent each of the employees a telegram saying that their resignations were effective immediately. b. Issue: How long does an offer made during a meeting stay open for acceptance? c. Holding: In face-to-face meetings, offers expire at the end of the meeting unless the offeror indicates that it will be kept open for a longer period of time. 5. Ardente v. Horan a. Facts: Ardente was interested in buying a house from Horan. Horan put the property up for sale. Ardente made a "bid" of $250,000 which was communicated to Horan by Ardente's lawyer. Horan's attorney informed Ardente's lawyer that the bid was "acceptable." Horan's attorney then sent a written contract to Ardente's lawyer including the terms of the agreement but without Horan's signature. Ardente signed the contract and Ardente's attorney sent it back to Horan's attorney along with a letter saying Ardente was "concerned" about certain furnishings being included in the sale. He asked for confirmation that these items were included because they would be difficult to replace. Horan then refused to sell to Ardente, and Ardente sued for specific performance of the contract. 25 b. Issue: Did the return of the contract along with the letter constitute an acceptance? c. Holding: No. Because the letter included additional terms it constituted a counter-offer and not an acceptance. Mirror image rule Acceptance “Manifestation of assent to the offered terms, made in the manner invited or required by the offer.” (Restatement 50) Offeror is the “master of the offer”; can dictate the time and manner of acceptance Acceptance must “mirror” the offer 1. Dickenson v. Dodds (revocation) a. Facts: Dodds delivered a written offer to sell some property to Dickenson. The offer said it "is to be left over until Friday at 9:00 a.m.," which was two days later. On the next day, Dickinson was informed by his agent that Dodds was intending to sell the property to someone else. Dickinson immediately went to the home of Dodds' mother-in-law, where Dodds was staying, and gave her a written acceptance of the offer. Dodds never received this document, however. On Friday morning before 9:00 a.m., both Dickenson and his agent saw Dodds at a train station and gave him duplicate copies of the acceptance. Each were told that the property had been sold to someone else. Dickenson sued Dodds for specific performance. b. Issue 1: If an offer says it is open for a period of time but the offeror was given no consideration to keep it open, can the offeror revoke the offer before the time has expired? c. Issue 2: If an offeree hears that the offeror is selling his property to a third party, is the offer deemed to be revoked? d. Holding 1: Yes. The offer to be held open until Friday 9 o’clock was not supported by consideration and therefore could be revoked before that time. e. Holding 2: Yes. An offer is deemed to be revoked if the offeree learns that the offeror has made other plans and no longer intends to reach an agreement with the offeree. Offer terminates upon: Expiration of a fixed time stated in offer Expiration of reasonable time, if no fixed time stated (Akers) Death or incapacity of offeror (p. 451-52) Rejection by offeree (Akers) Counteroffer (Ardente) Revocation by offeror (Dickenson) 2. Millis Mgmt. v. Joppich 26 a. Facts: Joppich agreed to purchase a residential lot from 1464-Eight, Ltd. and Millis Management Corporation for $65,000. At the time of closing, Joppich and the seller executed a separate option agreement, by which the seller could repurchase the property if Joppich did not commence construction on the lot within 18 months after closing. The option agreement recited Joppich’s receipt of a ten dollars paid by the sellers. Joppich failed to commence construction of a residence within the requisite time. Seller sought to exercise the option and buy back the lot. Joppich sued for a declaratory judgment stating that the option agreement was invalid for lack of consideration because the ten dollar option fee had never been paid. b. Issue: Is a false recital of nominal consideration sufficient to form a binding option contract? c. Holding: Yes. A recital of nominal consideration being paid is sufficient to form an option contract even if the money was not paid. UCC 2-205 (“firm offers”) (1) An offer (2) by a merchant to buy or sell goods in (3) a signed writing which (4) by its terms gives assurance that it will be held open: is not revocable for lack of consideration during the time stated or if no time is stated for a reasonable time but in no event may such period of irrevocability exceed three months but any such term of assurance on a form supplied by the offeree must be separately signed by the offeror. 3. Irrevocable offers (options): Ragosta v. Wilder a. Facts: Plaintiffs wanted to purchase “The Fork Shop” from defendant. Plaintiffs mailed defendant a letter offering to purchase the property along with a check for $2000 earnest money. Defendant returned the check with a counter offer saying defendant would sell to the plaintiffs for $88,000 if defendants appeared with defendant at a certain bank with said sum by a certain date, providing that the property has not been sold to someone else before that date. Several weeks before the deadline, defendant told plaintiffs that he no longer wanted to sell to plaintiffs even though The Fork Shop had not yet been sold. Plaintiffs responded that they had arranged for financing and were prepared to appear at the bank by the deadline with the full purchase price. They had incurred over $7,000 in closing expenses and sued for specific performance. b. Issue: If someone makes a unilateral offer and the offeree spends a substantial amount of money preparing to do the requested performance, is the offer no longer revocable by the offeror? c. Holding: Yes, under the doctrine of promissory estoppel an offer can be made irrevocable if the offeree reasonably relies on the offer. 27 4. Drennan v. Star Paving a. Facts: A general contractor was preparing a bid to build a school. It was customary for subcontractors to telephone their bids shortly before the bid would be submitted. The general contractor received 50-75 subcontractor bids for the school job, including a bid for the paving work from Star Paving for $7,131.60, which was the lowest bid. The general contractor included this amount in its bid to construct the school. The general contractor was awarded the contract. Before the general contractor could tell Star Paving that it had the job, Star Paving claimed there was a mistake and that they would not do the work for less than $15,000.The general contractor found a substitute contractor who would do the work for $10,948.60. b. Issue: When a general contractor uses a subcontractor's bid and is awarded the contract, can the subcontractor revoke its bid before the general contractor formally accepts it? c. Holding: No. Using the subcontractor's bid makes the bid irrevocable. When is an offer not revocable? Offeree relies (Rest. 87(2) or 90) Offeree begins performance (unilateral offers only) (Rest. 45) “Option” is purchased with consideration Joppich (even nominal consideration) UCC 2-205 (“firm” offer statute) Acceptance Manifestation of assent to the offered terms, made in the manner invited or required by the offer Offeror is the “master of the offer” Can dictate the time and manner of acceptance 1. Keller v Bones a. Facts: The Boneses listed their ranch for sale. Keller made a written offer and sent it to the Boneses’ real estate agent. The offer stated that it would become a binding contract upon execution by the Boneses. The offer also stated that it would expire by its own terms if not accepted by July 21 at 5:00 p.m. The Boneses signed the offer at 4:53 p.m. on that date. The Bonses' agent phoned Keller to inform him of the acceptance at 5:12 p.m. by leaving a message on his voicemail. On the following day, the Boneses received another offer and informed Keller that they would not sell to him. b. Issue: If an offer states that the contract becomes binding if the offeree signs it before a certain deadline, and the offeree does sign before that deadline but does not inform the offeror about the acceptance until after the deadline has passed, is the contract binding? 28 c. Holding: Yes. A contract is binding if the offeree complies with the offered terms and signs the agreement before expiration of the deadline even if communication of that acceptance comes after the deadline has passed. Bargaining at a distance Unless the offeror indicates otherwise, an acceptance is effective when sent by the offeree (“mailbox rule” or “posting rule”). All other communications (rejections, counteroffers, revocations) are effective when received by the other party. Mailbox rule offer is considered accepted at the time that the acceptance is communicated Silence as acceptance 2. McGurn v. Bell Microproducts 3. Facts: After a period of negotiations, Bell Microproducts made a written and signed employment offer to McGurn providing, inter alia, that if he was terminated without cause within the first 12 months of employment, Bell would pay him a certain amount of money. The offer stated that McGurn should return the contract to the office of human resources at Bell. McGurn signed the offer and returned it to the HR office as requested, but he changed "12 months" to "24 months." Bell did not notice the change until McGurn had worked almost one year. In the thirteenth month of McGurn's employment, Bell terminated McGurn without cause and refused to pay him the stated sum of money. 4. Issue: Did Bell accept McGurn's counteroffer, as a matter of law, by not objecting to it and allowing him to work at the company for several months? 5. Holding: No. Silence does not constitute an acceptance. There is an exception, however. Where an offeree takes the benefit of offered services and either knew or had reason to know about the offered terms, and had a reasonable opportunity to reject them, a failure to object can constitute acceptance by silence. Duty to speak: Acceptance by silence (Rest. 69) (1) Where an offeree fails to reply to an offer, his silence and inaction operate as an acceptance in the following cases only: Where an offeree takes the benefit of offered services with reasonable opportunity to reject them and reason to know that they were offered with the expectation of compensation (b) Where the offeror has stated or given the offeree reason to understand that assent may be manifested by silence or inaction, and the offeree in remaining silent and inactive intends to accept the offer. (c) Where because of previous dealings or otherwise, it is reasonable that the offeree should notify the offeror if he does not intend to accept. 29