INFORMATION TO USERS

The most advanced technology has been used to photo­

graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm

master. UMI films the text directly from the original or

copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies

are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type

of computer printer.

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the

quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print,

colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs,

print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper

alignment can adversely affect reproduction.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a

complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these

will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material

had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.

Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re­

produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the

upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in

equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also

photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced

form at the back of the book. These are also available as

one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23"

black and white photographic p rint for an additional

charge.

Photographs included in the original manuscript have

been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher

quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are

available for any photographs or illustrations appearing

in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly

to order.

U niversity M icrofilm s In tern atio n al

A Bell & Howell Inform ation C o m p a n y

3 0 0 N o rth Z e e b R o a d . A nn Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 -1 3 4 6 USA

3 1 3 /7 6 1 -4 7 0 0

8 0 0 /5 2 1 -0 6 0 0

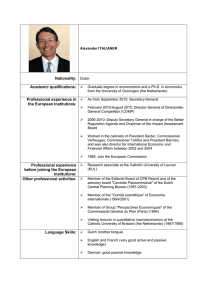

Order Number 891056G

The yeom an ideal: A D utch fam ily in the M iddle Colonies,

1660-1800

Fabend, Firth Haring, Ph.D.

New York University, 1988

Copyright © 1988 by Fabend, Firth H aring. All rights reserved.

UMI

300 N.ZeebRd.

Ann Arbor, MI 48106

The Y e o m a n

Ideali

D u t c h F a m i l y 1n t h e M i d d l e C ol o n i e s ,

Firth Haring

1 6 6 0 - 18 00

Fabend

S u b m i t t e d 1n p ar t i a l f u l f i l l m e n t of the

r e q u i r e m e n t s f or t h e d e g r e e

of D o c t o r of P h i l o s o p h y

1n t h e G r a d u a t e S ch o o l of A r t s and S c i e n c e s

New York U niversity

1988

(c) Copyright by

Firth Haring Fabend

Contents

Acknow1edgments

Preface

Part I. The First and Second Generations

1.

New Netherland Beginnings

2.

3.

"A Cartaine trackt of Landt named ould tappan"

First Fami1ies

Part II.

Part

The Second and Third Generations

4.

"A Gallant Plentiful 1 Country"

5.

A Prosperous Minority

6.

When Flesh Must Yield Unto Death

III.

7.

The Fourth and Fifth Generations

Religion! "Those Who Labor in the Earth"

8.

Politics! Seeds of the Republic

9.

"A Spirit of Independency"

10.

Getting on for One's Self

Genealogical Chart

Bibliography

i

T a b tes

Tab 1e 5-1.

Child-Bearing Patterns, Second and Third

Generations

Table 5-2.

Child-Bearing Patterns, Fourth Generation

Table 5-3.

Child-Bearing Range,

Generation

Table 5-4.

Child-Bearing Patterns,

Fourth Generations

Table 6-1.

Women Taxed in Harington Township, Bergen

County, N.J., September 1779

Table 6-2.

Distribution of Testators' Real Property

Among Sons and Daughters, New York City,

1664-1750

Table 6-3.

Disposition of Property, Real and Personal,

Third Generation

Table 7-1.

Haring Men Joining Tappan Reformed Church,

1694-1751

Table 7-2.

Haring Women Joining Tappan Reformed Church,

1694-1751

Table 8-1.

Members, Board of Supervisors,

County, N.Y., 1723-1750

Table 8-2.

New York General Assembly,

Family, 1701-1768

Table 10-1.

Disposition of Property, Real and Personal,

Fourth Generation

Table 10-2.

Comparison of Wealth, Third and Fourth

Generations, Selected Testators

il

in Years, Fourth

Second, Third, and

Orange

Service, Haring

Figures

Figure 1-1.

"New Amsterdam now New York," in

1660s.

Figure 1-2.

The Manatus Map.

1639

Figure 1-3.

The Castello Plan.

Figure 2-1.

Outline Map of the Tappan Patent

Figure 2-2,

Tappan in 1745, by Philip Verplanck,

Surveyor

Figure 2-3.

Tappan Patent in 1727

Figure 3-1.

Census of Orange County,

Figure 4-1.

Reconstructions of Johannes Winckelman's

Farmhouse

Figure 4-2.

House Built by Daniel De Clark,

Figure 4-3.

De Clark's House,

Kitchen

Figure 4-4.

De Clark's House,

Fireplace

Figure 4-5.

De Clark's Housa,

c. 1847

Figure 4-6.

Haring-DeWo1f House, Old Tappan,

Figure 4-7.

Kitchen of an Eighteenth-Century Haring

House, c. 1912

Figure 4-8.

An Eighteenth-Century Bergen County Kas

Figure 4-9,

Reconstructed Perspective of a New

Netherland House-Barn, 1641

Figure 4-10

A Bergen County Dutch-St^le Barn

Figure 4-11.

Roof, Floor, and Elevation of a Hay Barrack

Figure 4-12.

The Van Bergen Overmantel

* .‘

v

ii i

the

Manhattan and Environs in

New Amsterdam, c. 1660

1702

1700

N.Y.

Figure 5-1.

Haring Farm in Lower Manhattan,

Figure 5-2.

Ratzer Map, 1766

Figure 5-3.

Eight-Room Tappan House, Built c. 1753

Figure 5-4.

Interiors of an Eighteenth-Century Haring

House, c. 1912

Figure 7-1.

Tappan in 1778

Figure 7-2.

Tappan Reformed Church,

1783

Figure 7-3.

Tappan Reformed Church,

c. 1694, and 1788

Figure 9-1.

Map of Baylor Massacre Site

Figure 9-2.

Excavated Dragoon Skeletons, Baylor

Massacre Site

Figure 9-3.

The "Neutral Ground" During the American

Revo 1ution

Figure 9-4.

The Landing of the British Troops in the

Jerseys, November 1776

Figure 10-1.

House of Frederick Haring, Built c. 1753

Figure 10-2.

Hoebuck Ferry House, New Jersey.

Figure 10-3.

Twin-door House, Surrogate Map 39,

September 15, 1810

iv

1784

Acknowledgments

Literally dozens of historians and librarians have helped

me over the past five years in tracking down the public

records and in locating the appropriate printed sources to

complete this study.

But the person to whom I owe the

greatest debt is Patricia U. Bonomi--both for her initial

enthusiasm for the project and for her consistent

encouragement and generous support and direction as it

proceeded.

The difficult challenge of rendering meaning

out of a seeming chaos of information was assisted

enormously by her astute guidance and unflagging

confidence.

I thank her!

Also most encouraging and helpful over the years have

been Paul R. Baker and Kenneth E. Silverman of the New

York University American Studies Program.

The final

manuscript reflects their helpful reading of an earlier

version, as it does the insightful comments of Thomas

Bender and David Reimers.

Other readers of individual chapters or parts of

chapters whose comments appreciably improved the final

results are David E. Narrett, Claire K. Tholl, and Thomas

B. Demarest.

Among local historians,

debt to Howard I. Durie.

1 owe the greatest

His patience and generosity

smoothed my way countless times.

Tappantown Historical Society,

To Sally Dewey of the

the Reverend James Johnson

of the Tappan Reformed Church, and to E. Haring Chandor I

owe particular gratitude for providing me with access to

important sources of information.

The staffs of the New-York Historical Society,

especially Thomas Dunnings,

Society,

the New Jersey Historical

the New Jersey State Library and Archives,

New York State Library,

the

the New York Public Library, Bobst

Library at New York University,

the Columbia University

libraries, Queens College Library,

the New Jersey Room of

the Alexander Library at Rutgers University,

Jersey Room at the Newark Public Library,

the New

the New York

Genealogical and Biographical Society Library,

vi

the

k

Rockland Room of the New City,

N.Y., Free Library,

Historical Society of Rockland County,

Institute of Technology Library,

the

the Stevens

the Johnson

Library in Hackensack, N.J., and the Rosenbach Museum &

Library in Philadelphia patiently and cheerfully produced

innumerable documents and printed sources for me.

Mr. Dunnings,

Wright,

I thank for particular kindnesses William C.

Larry Hackman,

Christine M. Beuregard,

Leo Hershkowitz,

Scott,

Besides

William Evans,

James D. Folts,

John D. Stinson,

Charles Cummings,

Brent Allison,

Yvonne Yare, John

Katherine Fogerty, and Jane G. Hartye.

For a research grant in 1985 1 am grateful

Jersey Historical Commission,

to the New

and for typing and

invaluable technological assistance

I appreciate Jayne

Saray and David J. Babcock.

Finally,

I have my family to thank: Carl, Caroline,

and Lydia for sustaining me over the long years with their

loving support, encouragement,

vi i

and good humor.

This work is dedicated to my mother,

Elizabeth Haring,

to the memory of my father, James F. Haring,

1906-1987.

and

Preface

Family history,

families,

especially of m id d 1e -c o 1ony farming-class

has been sorely neglected.

Few studies exist that

locate a particular family of the yeoman or "middling" sort

in any of the thirteen colonies and examine it in a

systematic and scholarly manner over the course of the

colonial period and after.

Yet to locate and reconstruct

such a family over four or five generations is to discover a

wealth of information about how ordinary seventeenth- and

eighteenth-century Americans weathered the immigrant

experience,

established themselves in a community,

in the social,

political,

economic, and religious

took part

life of

their time, coped with a contury and a half of enormous

social change, and adjusted to conditions in the new

republic.

This aspect of our national experience has been passed

1

over because of the difficulties in "getting at" such

families.

letters,

They did not leave the rich cache of diaries,

journals,

and account books that offer insight into

such upper-class colonial

families as the Beekmans,

Gansevoorts,

or Schuylers,

Livingstons,

to name only a few

m i d d 1e - c o 1ony families that have been investigated.

To gain

a sense of the middling sort requires a different approach,

and a difficult one. Their

lives must be reconstructed

through the public record: church and cemetery records,

deeds,

wills,

inventories,

court,

town,

tax, and military

records--a task more easily described than carried out.

The Haring family is ideal

for such a study.

Its

beginnings in Manhattan in the 1660s are documented

records of the New York Dutch Reformed Church;

in the

its decision

to leave New York after the British Conquest and resettle on

land on the west side of the Hudson River is a matter of

record;

its motives for

leaving New York are clear;

stayed in one place--Orange

Bergen County, N.J.,

(indeed,

(now Rockland) County,

N.Y.,

and

for the entire eighteenth century

it is still there); and its experience and behavior

can be traced In surviving church,

military,

it

land,

town,

tax,

court,

and probate records for the entire period under

consideration.

As a bonus,

a number of the houses the

family built and lived in over the course of the eighteenth

century still stand--rich "primary sources" in themselves.

John Pietersen Haring,

progenitor of the family in

America,

came from Hoorn in the province of North Holland.

A

scrutiny of the records pertaining to Haring in this country

discloses that he had four sons, eleven grandsons,

twenty-nine great-grandsons,

great-great-grandsons,

and seventy-five

almost every one of whom can be

traced in the public records of New York and New Jersey.

also had an equal number of female descendants,

but as daughters and granddaughters married,

members,

for practical purposes,

(He

of course,

they became

of their husbands*

fami lies.)

As we explore the records of these 120 men and their

wives and children,

practices,

dreams,

their politics,

religion,

domestic life and, of course,

inheritance

their hopes and

successes and failures over the course of five

generations,

a textured and satisfying portrait emerges of a

colonial American family.

And yet the picture that emerges out of the great

welter of records is in one respect puzzling,

for it is one

of a Dutch family whose retention over many generations in

America of its Dutchness may suggest a deep ambivalence

toward America and toward becoming American.

this possibility,

this study will

To explore

look at this farming-class

family in relation to what has been called the yeoman ideal:

the vision of America,

set forth by Thomas Jefferson in his

Notes on the State of Virginia in 1785, as a nation of s m a l 1

independent farmers

living justly,

happily,

and equitably in

a state of republican "virtue."

The Harings,

yeoman ideal

as we will see, pursued the so-called

from their arrival

by the standards of the day,

models of good husbandry,

in America,

ideal yeomen.

Their farms were

their families were healthy,

housing stock was excellent for the period,

nutritious,

their

levels high.

offspring,

life expectancy

They prospered,

worshiped God,

colonial militias,

and they were,

their

their diet was

long, and their fertility

provided well for their

served as officers in their

shouldered the main burden of

administering their town and county governments,

and they

participated in a significant way in province-1evel

political affairs.

certain moral

To men like them no wonder adhered a

luster.

No wonder Benjamin Franklin and

Thomas Jefferson saw in their example a paradigm for the

nation.

"Those who labour in the earth," Jefferson wrote in

his Notes on Virginia,

"are the chosen people of God . . .

whose breasts- he has made his peculiar deposit for

substantial

and genuine virtue."

declared at midcentury that,

Cadwallader Colden

in the whole society,

were the most useful and the most moral.

Crevecoeur,

an Orange County,

N.Y.,

farmers

And St. John de

farmer,

described

America in 1782 as a "people of cultivators . . . united by

the silken bands of mild government,

. . . because they are equitable.

for whom we toil,

all respecting the laws

. . .

We have no princes,

starve, and bleed: we are the most perfect

society now existing in the world."

Yet after the Revolution the Harings and other

Dutch-descended farmers in the Hackensack and Hudson valleys

began to disappear from the colonial assemblies where they

had been prominent

in earlier generations.

perceived by observers as Dutch,

not American,

had been in America for 150 years.

although they

And they were to play

almost no part at all on state or national

nineteenth century.

They were

scenes during the

When Washington Irving,

born in 1783,

came in 1820 to write of his Hudson Valley neighbors,

quaint Dutchmen in calico pantaloons,

frontiersmen,

see,

radical

centuries.

not the American

politically minded farmers,

patriots

he saw

and,

as we will

(or loyal British) of the previous two

They had visibly retired after the Revolution

into "Dutchness."

What accounts for the withdrawal

of the Dutch American

farmer from the stage of the new republic?

persistent Dutchness?

And what,

Was it his

in fact, could Dutchness

have been to a "Dutch" family after five generations in

America?

For the Haring family and other Dutch American

farming-class families

like them, was Dutchness at the end

of the eighteenth century a defense against the painful

process of change,

Jefferson,

now enthusiastically endorsed even by

from an agricultural

to a commercial

society?

Did all they treasured of security and stability,

and independence,

of the familiar ways of their

5

of freedom

fathers--indeed,

of the values of the yeoman ideal

itself--lie in something that had been Dutch before it was

American?

Did the descendants of the Dutch families revert

in the nineteenth century to .s remembered golden age, a

reinvented Dutchness?

If so, how accurate was the memory?

Or were the Dutch in America ambivalent from the beginning

about America and about becoming American?

Answers can be forthcoming only by first looking closely

at a Dutch-descended family of the farming class,

reconstituting it in the only way possible,

through the

public record, and examining its structure,

values, beliefs,

aspirations,

expectations,

and its history--the totality of

its experience in America--from New Netherland to the new

republic.

6

Chapter 1

New Netherland Beginnings

On May

Street,

18,

1662,

in the Out-ward of Manhattan,

north of Vail

an obscure Dutchman took a b.ide in the recently

constructed chapel on Peter Stuyvesant's "bouwerie" or farm.

The bridegroom was John Pietersen Haring,

emigrated from Hoorn,

the Netherlands,

bride was Grl.etje Cosyns,

whose family had

in the 1630s.

The

born on Manhattan Island in 1641,

the daughter of Cosyn Gerrltsen.1

John and Grietje were married by Domine Henricus Selyns,

minister of the Dutch Reformed Church in New Amsterdam,

and

the first pastor of the new chapel on Governor Stuyvesant's

farm.

Selyns has given us a brief account of the Bouwery

Village in the 1660s:

pleasure," he wrote,

It is a ^place of relaxation and

where "people go from the Manhattans

[that Is, "downtown"] for the evening service [on Sundays].

There are there forty negroes,

coast,

from the region of the negro

besides the household families."3

The Bouwery was one of two farming villages in the

Out-ward--the rural district north of Wall Street.

other was Harlem,

farther to the north,

The

settled in 1661.

The Bouwery was definitely a nice place to live in the late

seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Maps show it as

an area of gently rolling meadows--with views of the East

River and Hudson River possible from almost any hill or

knoll--ponds,

streams,

marshlands,

sandy beaches,

dotted with neat palisaded farmhouses,

South of Wall Street,

and fields

barns, and hay ricks.

the thriving "city" was described as

"built most of Brick and Stone, and covered with red and

black Tile [roofs.

Aspect.”3

It] gives at a distance a pleasing

(See Figure 1-1.)

New Netherland,

in general,

was, according to one

testlmonia1,

under the best clymate in the whole world; . . .

seed may bee thrown into the ground, except six

weekes, all the yere long; there are

five sorts of grape wch are very good and grow

heere naturally, with diverse other excellent fruits

extraordinary good, and ye fruits transplanted

from Europe far surpasseth any there; as apples,

pears, peaches, melons, etc. ETlhe landt,] very

fertile, produceth a great increase of wheat and all

other grane whatsoever; heere groweth tobacco very

very good, it naturally abounds, with several 1 sorts

of dyes, furrs of all sorts may bee had of the natives

very reasonable; store of saltpeter; marvelous plenty

in all kinds of food, excellent veneson, elkes very

great and large; all kind of land and sea foule that

are naturally in Europe are heere in great plenty, with

several 1 other sorte, ye Europe doth not enjoy; the sea

and rivers abounding with excellent fat and wholesome

6

in ffl

vo ai

;*.t

:,*i^:

-JsT

v'-‘>!,‘^i

’•v

Vr.i.V-

,;

<u c 4-1

fish wch are heere In great plenty.

The optimal

...

4

strategy of a young man in this

Edenic-sounding place was to acquire land and a source of

income, marry a woman with a good marriage portion,

meet

the people who would put opportunity in his path, and

accumulate a nest egg that would provide him with a

certain freedom of action.

By marrying Grietje Cosyns,

John Pietersen Haring did well

indeed.

She was already

a widow, and one with assets to her name, although she

was only twenty-one.

their seven children,

Uithin twenty years,

this couple and

along with twelve other families,

would cooperatively purchase 16,000 acres and leave

Manhattan Island to start a new life farming across the

Hudson River.

The Yeoman Ideal

Jefferson's veneration of the farmer and the agrarian life

was, of course,

not original with him.

The tradition

reached back to the ancient Greeks and Romans, and the

farming life was extolled by writers of the Middle Ages,

Renaissance,

the

and the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

"Of all the occupations by which gain is secured," Cicero

wrote,

"none is better than agriculture, none more

profitable, none more delightful, none more becoming to a

freeman."

As a modern historian put it, "Since agriculture

9

was the basic economic enterprise [from time immemorial],

is not surprising to find it sanctioned by religion,

secular idealism,

by

by whatever forms in which the propensity

for rationalization found expression.

farmers;

it

Almost all men were

therefore to think well of man was to think well of

farming."9

By the time Jefferson in 17B5 wrote to John Jay that

"Cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens.

They are the most vigorous,

virtuous,

the most independant,

the most

and they are tied to their country and wedded to

it’s liberty and interests by the most

lasting bonds," John

Pietersen Haring and his descendants had been farming in

America for 150 years,

York and New Jersey.

as farmers,

first in New Netherland,

then in New

There is every reason to believe that,

they too shared a good opinion of the farming

life and had a we 11 - formu1ated notion of where the farmer

stood in the social

hierarchy of their day.4

Some time after the British Conquest of New Netherland,

the Harings began,

as did other American

farmers of a

certain substance,

to identify themselves in legal documents

as yeomen, an English term denoting an owner of a small

landed estate,

a freeholder under the rank of gentleman, a

countryman of respectable standing and an Independent

from cultivating his own land.

living

In choosing this term,

rather than the simpler farmer, yeomen marked their status

at the top of the various ranks of tillers of the soil that

10

Included, besides

also

landowning smaller farmers or freeholders,

leaseholding farmers,

servants,

farm hands,

farm apprentices,

seasonal workers,

farm laborers,

farm

various sorts of hired hands and

indentured servants,

and slaves. They also

marked their relationship to those directly above them in

the social order,

gentlemen.

By the eighteenth century,

they had prospered sufficiently to begin identifying

themselves in documents as both gentlemen and yeomen.

The term yeoman and the concept of a category of

agriculturalist with a certain relation to the nobility

first appears in the English language in the early fifteenth

century.

It is crucial to an understanding of the farmer in

colonial America,

particularly as Jefferson viewed him--that

is, as the figure upon whom the republic was to rest--to

know that, as early as the late Middle Ages in England,

yeomen played a political

and were regarded as,

role.

They served in parliament

in the social hierachy, directly under

"Knyghtes and Esquiers [with whom they] had ledynge of

men."7

In discussing a family of Dutch origins, however,

it is

even more important to know that the relationship between

the farmer and the polity was by no means exclusively of

English origins.

The "yeoman ideal," broadly speaking,

had

an even more venerable history in the Netherlands than in

England. The Dutch commoners'

traditions of both landowning

and self-government were well established early,

11

it is

thought,

because of the failure of the Dutch nobility to

protect the people on the coast from the depredations of the

Normans.

Forced to defend themselves from the Normans in

the tenth century,

had become,

the inhabitants of the Dutch coastlands

by the eleventh century,

recognize no central authority.

so independent as to

By the thirteenth century,

bondage in all parts of the Netherlands was virtually a

"thing of the past," and feudalism,

social order,

framework,

with its three-tiered

had no chance of becoming a workable social

as, of course,

it had in Britain and France.

the Netherlands only two classes mattered,

commoners,

in what was,

nobles and

even in the Middle Ages,

"curiously democratic rural society."*

In

a

Thus the farmer from

the Dutch Republic came to America in the seventeenth

century with his yeoman ideal

intact: He would own his own

land and challenge the ruling class when it trespassed

4

against his constitutional

rights and

liberties.

A First-Generation Role Model

Midwives to the birth of the yeoman Ideal

in the

Middle

Colonies were the Netherlands government and the Dutch Vest

India Company.

In the 1630s, young Dutchmen like Pieter

Janszen and Cosyn Gerrltsen,

father-in-law,

John Haring*s father and

were perusaded to emigrate to New Netherland

by the promise of the home government and the Dutch West

12

India Company to supply those who wished to farm with as

much tillable,

pasture, and hayland as a man with his family

could till: "from twenty to thirty morgens [40 to 60 acres]

upon condition that [this land] . . . within two years . . .

be brought into cultivation."*

Some time in the 1630s, Cosyn Gerritsen almost

certainly acquired his first property in New Amsterdam under

these terms,

though exactly when is not clear.

His farm or

"bouwerie" appears as #41 on the Manatus Map, M a n h a t t a n

Lying on the North River," made in 1639.

(See Figure 1-2.)

The policy of the Dutch West India Company was to allow a

colonist to hold and occupy his land without paying anything

for it for ten years (Article 22), calculating these years

from the time the land was "first sowed or mowed."

Cosyn Gerritsen*s formal patent dates from 1647,

Since

it may be

that he had first "sowed or mowed" Bouwerie #41 as early as

1637 and erected at that time the combination house-barn

structure that appeared on the Manatus Map two years later.

The farm was approached along "Cosyn Gerritsen's Uagon Way,"

known today as Astor Place and Eighth Street.10

That Astor Place and Eighth Street were known in 1662 as

Cosyn Gerritsen's Uagon Uay speaks to the already long and

successful

Nether land.

history of this particular Dutch farmer in New

ByJ662,

Cosyn Gerritsen had lived for a

generation in New Amsterdam, and his activities there, as

reconstructed from the public record,

13

illustrate the ways in

/* >

j? vi'-'H'i

: <i - H

; ‘ ;->T Y -.r\

; w

•r : ;

'

4 . f IV':'/'

*

■£■:

.1 *■»

co oo

- 0 »

]

6 jSUWlH

0 -H CO

CU t s CO

CO CO (0

JJ M U

•H T J 0 0

M

C

k M O

Mislitj

Q) 3 U

O O

6 o-i

C ^ O

0

ra o >i

0 0 3-1

U <3 to

3-1

X

•“ •!-(

CTi *i-0

cn

c!

vO >s

i—I CO

•

O rH

C O

•H

CO

0

0 -H

n o w

CO > -rH

3-1

4->0O

CO O

4-1

• ;t '! ' f

, 0 PQ 4 J

G =

CO

E

co

o

iH

1-4 CU

•-o-X

0,

4-1 U

cO 3-4

E 0) U Q

CO

B

•

CU

4J

-

0 0 <4-1 C

4J 0 CO O

03

4-1

0 CO O 60

CO t H vO 0

S

VO -H

6 1-1-G

CU 3-4

CO

XI 0 *H 0

H cw O tS

;. ^»j u S —

:^ T !5 l

OJ

I

rf:i-

.•i•j#

*'*i > '' '.'*'«•‘u

Q)

M

G

60

•H

Pk

‘V

" ";•' ..*.'•.••• \

Hi.,.

*•.*

which,

in pursuit of betterment,

the earliest Dutch farmers

rose.

Whether in the seventeenth century,

the Dutch

farmer's idea of betterment was consonant with what

Jefferson,

a hundred and fifty years

later, would think of

as a model for the repub 1ic--the small subsistence farmer

tilling his fifty acres--seems,

indication,

doubtful.

Rather,

if Gerritsen's career is any

the seventeenth-century farmer

was more enterprising and more entrepreneurial,

land not for subsistence,

using his

but for the enhancement of his

economic status and the advancement of his family's

opportunities and position.11

Though John Haring1s father, Pieter Janszen,

seems to

have rented his land from Patroon Kitiaen van Rensselaer,

who

sought to attract unemployed farmers,

hands, and laborers,

farm boys, farmers'

farm servants,

apprentices, and

house servants to toil on his huge patroonship south of

Albany on the Hudson River, Cosyn Gerritsen could choose not

to rent, but to become a freeholder in Manhattan.13

Determined to succeed in the New World,

himself better than many immigrants,

to farm,

he had prepared

for besides being able

he had a second occupation as a wheelwright:

Thus

"Cosyn Gerritsen's Wagon Way."13

Real estate as well as wheelwrighting and farming

served Cosyn Gerritsen's goal of advancement in America, and

land deeds document how he purposefully managed a slow but

steady improvement in his economic status as he bought and

14

sold property.

Activity In real estate speculation among

landowners In early Manhattan was widespread.

farmers

Even small

like Gerritsen very early on were selling parts of

the farm

land they had received free as colonists,

subdividing and selling their separate house

purchasing other

lots with

the proceeds,

free wheeling in Manhattan

real

estate

lots,

and in short were

in miniature

reflection of the speculation taking place on a

in the hinterlands by the great

Philipses,

Van Cortlandts,

large scale

land barons of the days

Schuylers,

Livingstons,

the

and

others.

Besides his 78-acre bouwerie,

almost exactly on the

site of New York University and Washington Square Park

today,

house

Cosyn Gerritsen had been granted

lot,

plus a smaller separate

"ye Great high w a y " --Broadway.

larger of these two

lots,

in 1647 a five-acre

lot on the west side of

In 1651,

he divided the

selling one part to Hendrick

Hendricksen and a house and

lot to Matys Capito.

These properties appear on

the Castello Plan,

Block C,

10, as houses #13 and #14.

(See Figure 1-3.)

The

subdivision

left Cosyn the smaller of the original

on Broadway for himself.

In 1656,

Lot

two

he bought a lot from

neighbor Teunis Nysen that was bounded by his own land.

sometime "before 1665," he came

ten-acre

lots

And

into possession of a

lot and farmhouse that he had probably had his eye

on for many years.

This house,

15

built in 1633 for Director

"iiM

General

Map,

Wouter Van Twiller,

appears as #10 on the Manatus

just to the northwest of Cosyn*s farm,

and its

acquisition by Cosyn was undoubtedly the jewel

crown.

in his small

(Cosyn Gerritsen probably moved his family into the

Van Twiller homestead in about

1660, as his old house on

Broadway was that year occupied by another party.)14

In short,

in 1662, when they married,

John P. Haring

and his bride had in Grietje's father a model

for success

and could comfortably anticipate their own prosperous future

in a New Nether land where opportunity under the Dutch

government seemed boundless and assured.

Within two years of their marriage,

Nether land was conquered by the British,

however,

New

and the future of

the Dutch farmer in Manhattan dimmed.

The American Dreamt

1664

Scholars disagree as to how dim the New York Dutchman's

prospects were in the

century.

last decades of the seventeenth

Thomas Archdeacon contends that it had become

sharply clear by 1674 that the Dutch and their descendants

were going to have to be content with a much smaller share

of the city's leadership and trade than they had originally

expected.

His comparison of tax rolls for New York in 1677

with those for 1703 show that in this interval the Dutch

declined dramatically from economic and social dominance,

16

by

1703 comprising 58% of the city's population but 52% of the

bottom economic groups.

he maintains,

The same two assessment lists show,

the English and French in 1703 residing in the

best new neighborhoods of the city, while the Dutch were

Increasingly having to resort to old poor, and new marginal

areas.

By the end of the eighteenth century,

he finds 80%

of the families in the city's poorest district Dutch, while

English and French "gentlemen" and "merchants," the top two

elite occupational designations of the period, outnumbered

Dutch gentlemen and merchants in 1703 60 to 36.

Increasing

numbers of Dutch worked as cartmen,

blacksmiths,

carpenters,

coopers,

and yeomen--al1 good

cordwainers,

silversmiths,

jobs, but not at the top of the ladder, by any means.19

On the other hand, Joyce D. Goodfriend,

using a

different method for analyzing the tax lists and focusing on

those of 1695 (as compared with Archdeacon's of 1677 and

1703),

finds that the years from 166,4 to 1700 were a period

of gradual adaptation and adjustment by the old settler

families to slowly changing conditions. The Dutch in the

so-called conquest cohort were losing ground to other ethnic

groups, but gradually,

not dramatically.

decades after the Conquest,

the population,

wealth.

the Dutch,

In 1695, three

representing 58% of

still owned 59% of the city's taxable

The English at 29.5% owned 26% of the wealth, and

the French at 11% owned 11% of the wealth--a remarkably

equitable division of resources. By 1703, however,

17

one of

the main indexes of wealth in the period--s1aveowning--shows

the Dutch in the bottom position relative to their numbers

in New York City and relative to the English,

French,

and

Jews.1*

A study of the farming village of Harlem at the north

end of Manhattan documents that children of the original

settlers there left Harlem in droves after the British

Conquest.

But whether they left for negative or for positive

reasons is debatable.

Benson,

Haldron,

Bogert,

Riker's genealogical accounts of the

Brevoort,

Kiersen,

Bussing,

Kortright,

Oblenis, Parmentier,

Delamater,

Low, Mantanye,

Tourneur,

Vermllye,

Dyckman,

Myer,

Nagel,

Vervelen,

and

Ualdron families show children flocking to New Jersey and'

New York across the Hudson in the

late seventeenth

century.17

however,

It seems

less likely,

that they were

rushing away from the British than rushing to embrace the

marvelous opportunities offered by relatively cheap and very

abundant

land.

A New Generat1on--A New Dream

From what can be learned of John Pletersen Haring*s

activities after his marriage to Grietje Cosyns,

he was

among those Dutchmen who continued to prosper, at

modest way, after the Conquest.

least in a

He had long since acquired

land adjoining his father-in-law’s in the Bouwery.

Documents are missing,

but PheIps-Stokes believed that

18

Haring purchased this property directly from one Solomon

Pieters,

who for speculative reasons had bought considerable

land in the neighborhood from Pieter Stuyvesant.

possible,

of course,

It is also

that Haring had purchased this

land

directly from his father-in-law and no deed was recorded.

But since none has surfaced,

it is even more likely that he

received the land from Cosyn Gerritsen as Grietje’s marriage

portion or that Grietje had inherited it from her first

husband.1•

Both in 1673 and 1674--when the Dutch briefly regained

ft*van,

control of New Nether land from the Eng 1ish--Haring was

elected a schepen,

or magistrate,

for the Out-ward.

Schepens received a salary for their services,

well as schout, burgomasters,

the clergy,

and they, as

and military and

civilian officers and their male descendants in New

Amsterdam also enjoyed the so-called Great Burgher Right,

entitling all who held it, and no one else (unless they paid

fifty guilders for the privilege),

carry on business,

vote,

to practice a trade,

and run for office.1’

John and Grietje Haring had. seven children together

between 1664 and 1661.

were Peter,

Cornelius,

1681.

Their four sons and three daughters

born in 1664; Vroutje,

1672; Brechtje,

1667; Cosyn,

1675; Marytie,

1669;

1679; and Abraham,

The baptisms of all but Peter are published in the

records of the New York Dutch Reformed Church.30

Within twenty years of his marriage,

19

then--and during

the first two decades of the British period--John Pietersen

Haring had acquired

land, probably followed a trade,

fathered seven children,

and foremost church,

affiliated with the city's first

participated in government, and as a

schepen enjoyed the privileges of the city.

other words,

in

achieved a modest but respectable place in the

city's society,

families,

He had,

below the great landed and merchant

but above the mass of unpropertied "mechanics" and

tenant farmers.21

He had also been accumulating enough capital

to leave

New York for greener pastures. The advent of the British had

coincided with a shortage of land on Manhattan

Island, and

the prescient Dutch farmer in New York had foreseen that

land was and would continue to become ever scarcer and more

expensive.

Yet land was, as we saw in the case of Cosyn

Gerritsen's rise, one of the keys to prosperity in

seventeenth-century New York.

The farmer prized it as more

than merely an arable stake, and more too than something to

pass on to his children.

He prized it for the speculative

opportunities it allowed him; as he knew, trading in real

estate was the tested means by which a man could improve his

economic position.

In 1681,

the year after his seventh and last child was

born, John Pietersen Haring and two of his neighbors in the

Out-ward signed a deed to purchase from the Tappaen Indians

a tract of land across the Hudson River that came to be

known as the Tappan Patent.22

That John Pietersen Haring would want to leave the place

he had called home for twenty years,

property,

his trade,

his church,

his wife's family,

his

his role in city affairs,

his children's best chance for an education,

and putting all

at risk strike out all over again in the dense wo 1f - infested

wilderness to the west is testimony both to his optimistic

assessment of the bright future he foresaw for himself and

his children away from New York--and to his dissatisfaction

with circumstances in New York.

Contemporary promotional

literature described the area

across the Hudson River from New York as "plentifully

supplied with lovely Springs,

in which are great store,

Fish,

and Uater-Fowl,

than . . .

In-land Rivers,

and various sorts of very good

much bigger,

in England."

and Rlvolets;

fatter,

and better Food,

Timber was, of course in plentiful

supply--to the point of being an encumbrance on the land,

but there were also "great quantities of open Ground by

Nature,

as well

Sheep, Cows,

fit for Arable,

Oxen,

sturgeon,

and Pastorage for

and Horses; which are . . .

good as the English."

and all sorts of

ks Meadow,

Deer,

as large and

swine, wild turkeys,

pigeons

land fowl were free for the taking, as were

lobster,

oysters,

and many other "Sea-Fish," and

rivers offered opportunity for considerable trade in wheat

and flour, beaver,

corn,

tanning,

tobacco,

iron, fish,

pork,

beef,

masts, and the building of vessels.33

21

salt,

In this teeming fertile wilderness,

their friends would have

land to farm,

their children and grandchildren,

for profit.

the Harings and

land to leave to

and excess

lands to sell

And once the ground was cleared and cultivated,

they would have an opportunity to sell their surplus produce

to the burgeoning city down river,

colonial New York merchants

imitating what the great

like Frederick Phil ipse,

Stephanus and Jacobus Van Cortlandt,

were already doing--acquiring

and Robert Livingston

land in the countryside and

milling grain for domestic and overseas sale.24

The ambitions of the Harings and their fellow farmers

in 1685 provide a startling contrast to Jefferson's rather

wistful

view in the Notes of 1785 of the ideal yeoman

as. a

subsistence farmer content to cultivate a small patch of

land, while his contact with nature improved his character

and inspired him with a love of republican government. Their

ambitions are more in line with Jefferson's more realistic

acknowledgment,

agricultural

also in 1785,

society was a

that his theory of an

"theory only."

In fact,

from wishing to live a subsistence existence,

far

it was the

plan of the Harings and the other Tappan settlers,

according

to a historian who in the 1880s interviewed their

descendants,

"to build a city which should eclipse all

rivals In the Colony save Its neighbor,

project does not seem absurd,

"wonderful agricultural

New York."

he commented,

This

considering the

resources of the Hudson Valley . . .

22

and the enormous profit to be obtained with the Indians in

furs."

Trade with the Indians was drawing to a close in

this area in the last decades of the seventeenth century,

but opportunities to sell wheat,

produce,

and

lumber through

middlemen to the Atlantic markets were growing.

southern tip of the Tappan Patent

The

lay close enough to the

head of navigation on the Hackensack River that men familiar

with the canal

system of the Netherlands could easily

envision building a canal

through the marshes

O r a d e l 1 Reservoir is today).

Then,

(where the

rather than shipping

down the Hudson to New York--where port duties were a

barrier to profit--they could transport their farm surpluses

and timber down the Hackensack River to markets

Jersey's free ports--not an illogical sbheme,

that the patentees believed the

in East

considering

land they were acquiring

lay

in East Jersey.29

Beyond their aggressive economic motives for

New York,

the Harings and their coventurers--thlrteen

families in all--also had religious and political

for moving away from the city in the 1680s.

in the Dutch Reformed Church,

ministers.

rights and

leaving

reasons

As dissenters

they were at odds with their

And as people accustomed to the constitutional

liberties the Dutch had fought for in the

Netherlands,

they were at odds also

with James

II, the

Roman Catholic King of Great Britain, and with the Catholic

governors James sent to administer his colonies

23

in America.

In Tappan,

they believed,

they could prosper economically,

form a church along the lines of their Pietist beliefs, and

govern themselves in a township protected by the conditions

of their Patent. Not of least Importance, they could build a

community of

likeminded friends centered around the family

life so dear to the typical Dutchman.

24

Chapter

Notes

1

1. Franklin Burdge, "A Notice of John Haring: a

Patriotic Statesman of the Revolution" (1878), unpublished,

unpaginated ms. Mss. division, New York Public Library. The

subject of B u rdge1s Notice was a great-grandson (1739-1809)

of John P. Haring and Grietje Cosyns.

(See Chapter 9.)

Burdge had access to a family Bible, location today

unknown, with biographical information in it.

On the

subject of John Pietersen H a r i n g ^ ancestry, he states that

he was a descendant of the John Haring who in 1573 had

distinguished himself against the Spanish at the Battle of

Diemerdyk in the Zuider Zee off Hoorn.

Haring, whose body

in full armor is buried in Harlem Cathedral in the

Netherlands, was shot dead on board the Spanish warship La

Inquisicion while attempting in another battle

to haul down the Spanish flag.

Accounts of the two

incidents in which he figured during the Dutch Revolt

against Spain are in John L. Motley, The Rise of the Dutch

Republic, A His t o r y . 5 vols. (New York, 1900), Vol. 3, pp.

359, 420-422. See also Richard H. Amerman, "Highlights of

History of Hoorn, North Holland," de Halve Maen. Vol. XLIV

(July 1969), no. 2, p. 9ff.

Pieter Janszen from Hoorn, North Holland, is described

in various genealogies of the Haring and related families

as the grandson of the sixteenth-century hero.

Diligent

search in the Netherlands fails to document descendants of

John Haring of Hoorn, however, suggesting that he was

childless at his death and stood in a collateral rather

than a direct relation to the Haring line in America. The

Hoorn archives indicate that a Pieter Janszen and Mary

Pieters, both from Hoorn, had a son, Jan, baptized there on

December 18, 1633, and in the Dutch way of naming, this

child would have been known as John Pietersen (son of

Pi e t e r ).

Pieter Janszen, a farmer, is mentioned in A. J. F. van

Laer, e d . , The Van Rensselaer Bouwier Manuscripts (Albany,

1908), as being in R e nsse1aerswyck on December 17, 1648,

and he was still there in 1666 (pp. 829, 838).

Cosyn Gerritsen was born c. 1608, probably in Putten

in the province of Utrecht. (In 1644, he testified

in court that he was "about 36 years of age," and numerous

documents describe him as "van Putten.")

With his wife

Vroutje, he had four children.

See Records of the Reformed

Dutch Church in New Amsterdam and New York (New York,

1901).

2.

7 vols.,

487-488.

Ecclesiastical Records of the State of New York.

ed. E. T. Corwin (Albany, 1901-1916), Vol. I, pp.

25

3.

(London,

Daniel Denton,

1670), p. 3.

A Brief Relation of New York

4.

Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the

State of New York, 15 vols., ed. E. B. Q'Callaghan and

Berthold Fernow (Albany, 1856-1887), Vol. Ill, pp. 30-39.

(Hereafter N.Y. Co 1. Docs.)

5.

For a recent discussion of Jefferson's agrarian

ideal, see Robert E. Shalhope, "Agriculture," Thomas

Jefferson^ A Reference Biography, ed. Merrill D. Peterson

(New York, 1986).

See also A. Whitney Griswold, "The

Agrarian Democracy of Thomas Jefferson," American Political

Science Review. XL (August 1946), 4, pp. 657-681; and

Griswold, Farming and Democracy (New York, 1948).

Cicero,

De Officiis. 1, xlii, Loeb Translation, p. 155, is quoted

in Griswold, Farming and Democracy, p. 20.

6.

Letter to John Jay, August 23, 1785, quoted in A.

J. Beitzinger, "Political Theorist," Thomas Jefferson! A

Reference Biography, ed. Merrill D. Peterson (New York,

1986), p. 91.

7.

Joyce Appleby has pointed out that the term yeoman

does not appear in Jefferson's Notes, that for Noah Webster

in the first American dictionary the word "retained the

social distinction of its British provenance but conveyed

nothing as such about farming," and that the term yeoman

appears in only 3 of 30,000 titles published in America

between 1760 and 1790.

Joyce Appleby, "Commercial Farming

and the 'Agrarian Myt h ’ in the Early Republic," The Journal

of American History. 68 (March 1982)’, 4, p. 837. The

explanation may be that, by the time of the Revolution,

Americans preferred to use American designations, rather

than one that smacked of a British tradition.

Countryman,

farmer, grower, husbandman, landowner, planter came to be

common designations; yeoman had been used and continued to

be used In wills. The quoted line is from the Oxford

English Dictionary.

8. Bernard H. M. Vlekke, Evolution of the Dutch

Nation (New York, 1945), pp. 31-32, 87, 22.

VII

9.

Article 21, N.Y. Colonial Mss..

(Vol. I), pp. 1603-56.

Holland Documents.

10. The Manatus Map is reproduced with a detailed

discussion in I. N. Phelps-Stokes, The Iconography of

Manhattan Island. 1498-1909.

6 vols. (New York,

1915-1928), Vol. II, plate 41.

11.

Article 22, N.Y. Colonial Mss..

26

Holland

Documents. VII (Vol. I), pp. 1603-56. After ten years, a

quitrent of one-tenth of the produce and increase of the

cattle was charged--a system known as free and common

socage.

The terms of the original Charter of Freeaoms and

Exemptions (1629) were improved in 1638 and 1640 to

encourage settlement, and In the following five years the

population of New Netherland doubled.

For Gerritsen, see

New York Historical Mss.i Dutch. Land Papers. GG. HH. II.

ed. and trans. Charles T. Gehring (Baltimore, 1980), p. 52;

and confirmation of May 26, 1668, Liber Patents, 111:50

(Albany), quoted in Phelps-Stokes, Iconography. Vol. VI, p.

129.

12. Oliver A. Rink, "The People of New Netherland:

Notes on Non-English Immigration to New York in the

Seventeenth Century," New York History. January 1981, p.

26.

13. Having an occupation in addition to farming was

important to success in the colonies, and double

occupations were common.

In New Netherland, skilled

tradesmen were in such demand that Van Rensselaer paid a

premium of 25% to obtain them.

Of the 102 emigrants to

Rensselaerswyck in the period 1630-44, 14X were carpenters,

masons, wheelwrights, millwrights, and carpenters*

apprentices; the services of cobblers, tailors, brewers,

coopers, bakers, weavers, blacksmiths, surgeons, and

ministers were slow in coming to the New World, but were

urgently needed.

Rink, "People of New Netherland," p. 23.

In Albany, N.Y., 126 of the 178 first-generation settlers

had two or more than two occupations or sources of income

and future profit.

Donna Merwick, "Dutch Townsmen and Land

Use: A Spatial Perspective on Sixteenth-Century Albany, New

York,"

The William and Mary Quarterly. 3d series, XXXVII

(1980), pp. 70-71.

The continuing need for labor was a

major stimulus to population recruitment and settlement

throughout the colonial period.

Bernard Bailyn, The

Peopling of British North America: An Introduction (New

York, 1986), pp. 60-64.

In June 1643, Cosyn Gerritsen hired Albert Cornelissen

"to make wheels and wagons [and] whatever is connected

therewith, for [the term] of one year."

If they should not

"agree together," the indenture reads, Albert "is to be

released at the end of six months; for which he is to be

paid in addition to his board, per annum, by Cosyn

Gerritsen, one hundred and ten guilders, and fourteen days

are to be allowed in harvest time when Albert shall be at

liberty to seek his own advantage."

N.Y. Hist. Mss. Dutch.

Vol. II, p. 139.

VI,

14.

See recitation in Phelps-Stokes, Iconography. Vol.

p. 129; Vol. II, pp. 238, 369; Vol. VI, p. 162.

See

27

also John A. Kouwenhoven, "Key to the Castello Plan," The

Columbia Historical Portrait of New York (New York, 1953),

pp. 41 and 42.

The Van Twiller farmhouse was visited in

1704, about fifteen years after Cosyn*s death, by the

traveling Madame Sarah Kemble Knight, who wrote: "Old

Madame Dowes [whose husband Gerard Douwes owned it then], a

Gentle-woman that lived at a farm House, . . . gave us a

handsome Entertainment of five or six Dishes and choice

Beer and metheglin, Cyder, etc. all which she said was the

produce of her farm.” Journal of Madam Knight (New York,

1825).

See also Phelps-Stokes, "The Van Twiller Homestead

Plot," Iconography. Vol. VI, p. 162.

Bailyn confirms that

land speculation was a "universal occupation" from the

beginning.

"Land speculation was everyone's Work," he

writes, and "Every farmer with an extra acre of land became

a land speculator."

Bailyn, Peopling, p p . 66-67.

A full

discussion is on pp. 65-87.

15.

Thomas J. Archdeacon, New York City. 1664-1710:

Conquest and Change (Ithaca, N.Y., 1975), pp. 51, 30.

16.

Joyce D. Goodfriend, "* Too Great a Mixture of

Nations’ : The Development of New York City Society in the

Seventeenth Century," diss. UCLA 1975, Table 29, p. 163;

Table 21; and p. 168.

Most of the mayors of. New York were

Dutch until 1691.

From 1689-1733, 32 percent of the New

York Common Council were lay officials in the Dutch

Reformed Church, and in the years 1734-1775 this percentage

increased.

Bruce Wilkenfeld, "The New York City Common

Council, 1689-1800,"

New York History. LI I (1971), pp.

249-273.

17.

James Riker, Harlem: Its Origins and Early

Annals. rev. ed. (New York, 1904).

18.

Phelps-Stokes, 1conographv. Vol. VI, p. 106.

Stokes notes that deeds for surrounding property mention

John Pietersen Haring as a boundary owner, sufficient

evidence to document his presence in the neighborhood.

19. Berthold Fernow, comp., The Records of New

Amsterdam from 1653 to 1674. 7 vols. (New York, 1897), Vol.

VII, p. 127. From 1652 to 1664, the year of the first

British conquest, a schout, three burgomasters, and five

schepens sat together in council in New Amsterdam and

"resolved" upon all subjects relating to the city.

(Their

British equivalents from 1664 to 1673 and again after 1674

were sheriff, mayor, and aldermen.)

Burgomasters were to

be chosen by the common burgers from the "honestest,

richest, and most capable men" In the city, and schout and

schepens also had to be of good character and

"understanding."

Schepens were empowered to give final

28

judgment on all cases involving sums of less than 100

guilders and had full power in all criminal cases.

See

New-York Historical Society Collections, The Burghers of

New Amsterdam and the Freeman of New York (New York, 1886).

20. Records of the Reformed Dutch Church in New

Amsterdam and New York (New York, 1901).

21. No tax records have survived for the Out-ward for

any year that John Pietersen Haring was alive.

Three

references in unpublished tax records for the Out-ward for

1699-1710 and 1721-1733 show the estate of a John Haring

being taxed long after John P. Haring was dead.

In 1702,

"John Harine house" in the Out-ward was valued'at 15

pounds, which put it on level 4 (2 being the lowest) of ten

levels of all properties taxed, according to a scale

devised using the 1677 tax rolls and a published roll from

1703.

The original hand-written records in bound volumes

are at the Hall of Records, 31

Chambers St., New York City.

They are also on microfilm, Reel A R - 1, Historical Documents

Collection, Queens College.

The scale is Archdeacon's in

New York City. 1664-1710. p. 161. After establishing

"population rosters" for the city in 1677 and 1703,

Archdeacon translated tax assessments, which.were based not

on actual wealth but on an estimated proportion of property

value, into scales of economic standing.

In 1703, those

taxed up to L5 were assigned to level 2, the lowest; up to

L10,

level 3; up to L15, level

4; up to L20, level 5; up to

L30,

level 6; up to L45, level

7, up to L70, level 8; up to

LI 10, level 9; and more, than L110, level 10.

In January 1708, "Mr. Haring" was taxed on L5; and the

following month, "John Haring Estate" was taxed on L5

again.

As late as 1721, "John Haring Estate and house"

were taxed on L5.

This property appears to have been the

nucleus of the much larger Haring or Herring farm seen in

the maps in Chapter 5 below.

22.

The deed from the Tappaen Indians is recorded in

Liber 4 of East Jersey Patents, pp. 17 and 18, in the

Office of the Secretary of State, Trenton, N.J.

The date

of purchase was March 17, 1681 (old style).

23.

From the legend on a map of the Province of

West-Jersey, 1677, John Carter Brown Library, Providence,

R. I.

24.

Sung Bok Kim, Landlord and Tenant in Colonial New

York. Manorial Society. 1664-1775 (Chapel Hill, 1978), Ch.

4 passim.

25.

See Shalhope,

"Agriculture," pp. 393-394;

29

Frank

B. Green,

The History of Rockland County (New York, 1886),

p. 39.

To build a trading city on the Hudson to rival all

others in New Jersey was hardly an absurdity in 1683, given

the location and rich natural resources of the area, the

energy of the settlers, and the small size of the existing

"cities."

See also Wilfred B. Talman in Tappan: 300 Years.

1666-1986. ed. Firth Fabend (Tappantown Historical Society,

1988), p. 22.

30

Chapter 2

**A Cartaine trackt of Landt named ould tappan*1

In attempting to explore why nineteenth-century

observers--Uashington

families

arrival

Irving,

in particular--considered

like the Harings Dutch,

in America,

200 years after their

1 have suggested that

Irving's

nineteenth-century Dutch-descended neighbors in the Hudson

Valley may have reverted to a remembered Dutchness of a

golden age in America when an ideal yeomanry--their

ancestors--had tamed and cultivated the wilderness,

harmony and p c ■ -e with their neighbors,

lived in

and practiced

equality and justice.1

How accurate a memory of the settler experience might

this have been?

his wilderness

neighbors?

How smooth was the Dutch farmer's access to

land?

How peaceably did he interact with his

How golden was the golden age his descendants

31

thought they remembered?

The process of acquiring

land in seventeenth-century New

York and New Jersey was a complicated one,

red tape,

time, and expense.

involving much

In 1809, Washington Irving's

satiric history of New York depicted the Dutch farmer as

bilking the Indians out of as much land as he could throw

his capacious pantaloons over,

but the reality in 1680 was

far different.

The buyer first had to locate the piece he wanted.

Then,

was,

if the land was "owned" by Indians, as the Tappan

land

the buyer had to ascertain if the Indians would sell

it, negotiate the terms with them,

and obtain "Leave . . .

from the Governour" to purchase it from them.

buyer came to terms,

and if the governor gave permission,

the license was filed,

General,

If seller and

the land was surveyed by the Surveyor

and a deed was drawn up.

The buyer with his

documents then went before the governor to petition for a

formal

grant or patent.

Finally,

he reappeared before the

governor again to receive official

Expenses involved in travel

locations,

parcel,

time to scout possible

perhaps to hire a translator to negotiate with

Indian owners,

government,

confirmation.2

plus travel expenses to the seat of

the cost of surveying the perimeter of the

legal fees, and various other expenses involved in

securing the governor's approval made the purchase of land

an expensive undertaking for men of ordinary means.

32

Thus

groups were formed to share the costs.

Thirteen men joined John Pietersen Haring in purchasing

land from the Tappan Indians.

the venture,

As the moving spirit behind

Haring purchased three of the total sixteen

shares,

one of which entitled the owner to about a thousand

acres.

The other thirteen men,

share,

were two Blauvelts,

Claes Manuel

in New

who each purchased one

three Smiths,

from the Bouwery,

John Stratmaker,

Garret Steynmets,

the patentees agreed to

Indians a hundred fathom of white wampum, 75 fathom

of black wampum,

kettles,

15 guns, A pistols,

one great kettle,

15 blankets,

8 small

10 shirts,

wedges,

adses,

hoes,

16

40 yards of duffel 1 cloth,

yards of another kind of coarse cloth,

hoes,

Ide Van

and Staats De Groot.

According to the Indian deed,

give the

and

and five men from settlements

Jersey--Corne1ius Cooper,

Vorst,

two De Vries's,

three coats, 8 great

40 pounds of powder, 50 pounds of

12 pairs of stockings,

10

1 cutlass,

2 gallons of rum, 4 casks of beer,

lead,

a tramell,

40 knives,

3

2

and 15 axes.

What they got in return was a territory the size of

Manhattan

Island in the eighteenth century: about 16,000

acres of fertile and well-watered wilderness teeming with

game and fish, and broken only by a few Indian trails,

perhaps a few natural meadows that did not need clearing,

and a few scattered areas the Indians had cleared for their

own purposes.

Eight to ten miles

33

long from north to south

and from two to five miles wide from east to west,

Tappan Patent

the east

the

lay in the valley between the Hudson River on

(though not on. the river) and the Hackensack River

on the west.

Suited for both farming and trading,

it was

entered by boat from the Hudson River--through property

owned by other parties--at the mouth of Tappan Creek.

On the

south it was within striking distance of the head of

navigation on the winding Hackensack River.

York State communities of Tappan,

Sparklll,

Norwood,

(Today,

the New

Orangeburg, Blauvelt,

and

and the New Jersey communities of Northvale,

Vest Norwood,

Old Tappan,

within the perimeter of the patent.

To own 16,000 acres of

and Harrington Park

lie

Figure 2L-1.)

land suitable both for farming

and for trading far exceeded the wildest dreams these men

could have had for themselves

in Europe,

or in Manhattan.

But before they had signed the final papers to secure its

ownership,

personal

a series of setbacks,

disappointments,

tragedies began to overtake them.

these occurred on December 7,

1683, when,

and

The first of

eighteen months

after signing the deed with the Indians, John Pietersen

Haring died.

families

Blauvelt.

The same month,

the heads of two other

in the venture also died:

Ide Van Vorst and Gerrit

And a fourth was soon to follow.

Cornelius

A.

Smith died sometime nbefore 1686.

To complicate matters,

at almost exactly the same time,

jurisdiction over the Tappan

land, which the patentees had

34

V*

■

H

2

*•

a. W

;

<

H

s

2

< 2 “

U *

I• °-t2i

z *■ — < i

J t < 5 s

=

O

2

°-:

<

*

w

ac

a

»3

■«

**

>w

S«

2

Q

O

w

o

2 1.

•'

i

/

(

a

*

o

/ ■H

9

./j—

I® / V

s/*>

Figure

-J

$

£©

K

z

Outline

Map

of the Tappan

Patent

f

believed was in East Jersey,

fell

Into doubt.

When Governor

Thomas Dongan claimed the territory for New York,

only confounded the patentees'

trading strategy,

he not

but set the

scene for rancorous border disputes that were not settled

until

1769.

"Paving noe Custom . . . Wee are like to bee deserted"

One of the patentees'

intentions in moving from New York to

what they thought was the Province of East Jersey was to

avoid New York port duties by trading wheat,

agricultural

Amboy,

timber,

and

surpluses through the free ports of Perth

Burlington,

and Phi 1a d e 1phia--a11 accessible to them

from their vantage point on the Hackensack River.

Common Council

of New York had other ideas.

But the

It coveted the

trade of New York's sister province across the Hudson River,

and on March 7,

1684,

the mayor and aldermen of New York

moved to frustrate East Jersey's trade ambitions

patentees'):

(and the

As the "unhappy Seperation of East Jersey

[doth) Diverte the Trade of this Province," they pointed out

to Governor Dongan,

"Wee doe humbley Suplycate your Honor

[to) Represent the Same unto his Royal 1 Highness . . . And

Desire that East-Jersey may be ReAnnexed to [New York)

. . .

Again by Purchas Or Other wayes."4

Governor Dongan agreed.

Council

In a report to the Privy

in London on the state of the province of New York,

he urged that not only East Jersey but also Connecticut,

35

Rhode Island,

three counties in Pennsylvania,

Jersey be annexed as well.

and West

As for East Jersey,

he reported,

it being situate on the other side of Hudsons

River and between us and where the river

disembogues itself into the sea, paying noe

Custom and having likewise the advantage of

having better land and most of the Settlers

there out of this Government.

Uee are like

to bee deserted by a great many of our

Merchants whoe Intend to settle there if

not annexed to this Government.

Last year two or three ships came in

there with goods and 1 am sure that the

Country cannot, noe not with the help of

West Jersey, consume one thousand lbs.

[sterling] in goods in two years soe that

the rest of these Goods must have been run

[that is, smuggled] into this Government

without paying his Majesty's Customs, and

indeed theres noe possibility of preventing

it.

And as for Beaver and Peltry, its

impossible to hinder its being carried

thither.

The Indians value not the length

of their journey soe as they can come to a

good market which those people can better

afford them than wee, they paying noe

Custom nor Excise inwards or outwards.9

As part of New York Colony rather than East Jersey,

Tappan was no longer as economically attractive as it had

been to men who had hoped to trade through East Jersey's

free ports, and three of the Tappan shareowners from East

Jersey now defected from the venture:

Cooper, Stratmaker,

and Steynmets either sold their interest in the Tappan land,

or retained it for their children to settle on when they

married.

With its leadership depleted,

Tappan was a smaller

community at the beginning than its founders had envisaged,

and it was poorer,

for now short on labor and capital

36

its

chances for development were sharply curtailed.

built the first temporary houses on the

the two sons of Gerrit Blauvelt,

surviving son Lambert,

Staats De Groot.

Those who

land were probably

Adriaen Smith and his

John De Vries and Claes Manuel, and

After Haring died,

his widow,

returned temporarily to the Out-ward.

Out-ward neighbor and widower,

Grietje,

When she remarried an

Daniel De Clark,

moved again to Tappan with him,

in 1685,

she

the seven Haring children,

and De Clark's son.*

Tappan was also,

demographies 11y speaking, a younger

community than it had expected to be.

Most of the

"patriarchs" of Tappan were very young men,

barely out of their teens.

some of them

The eldest Haring son Peter,

was assigned one of his father's three shares, was

Tappan by September

1667,

living in

when he signed the Oath of

Allegiance to the British king.7

married.8

who

Peter

His younger brother Cosyn

[2 1 ]

[ 2 3 ] ,

was

23

and

who was only

14

when their father died, was assigned the second of the three

shares.

He married in about

first house that year, at age

Haring brothers,

Cornelius

1692

and probably built his

2 2 .

The third and fourth

[ 2 4 ]

and Abraham

establish their families on the land in

they were

in

1 6 8 5 ,

21

and

2 6 .

1693

[ 2 7

j

and

Even De Clark was young.

began to

,

1 7 0 7 ,

when

At about

he was thirteen years Grietje Haring's junior.*

Early Trading Activity? A "oasaee thro the meadow"

37

31

The patentees'

slow start toward their goal of economic

betterment was exacerbated in the 1680s and 1690s by

official

economic policy that furthered not only New York's

welfare over East Jersey's,

interests over Dutch.

exports and imports,

but also English merchant

Governor Dongan's new laws regulated

ended any

legal trade between the city

and Amsterdam by forbidding the entry of foreign vessels

into New York City,

and in general made the smuggling

activities between New York and Amsterdam that had

characterized the decade immediately following the English

Conquest of New Netherland harder to pursue.

stricter mercantile regulations,

high seas,

and higher taxes,

on the Hudson River,

wars,

But despite

French piracy on the

a brisk sloop trade flourished

with merchant ships visiting

settlements on both banks of the colony's main north-south

artery to obtain country goods,

furs, and hides from farmers

and trappers.'0

With the ports of New Jersey effectively closed to

them,

the patentees*

next best hope was to trade down the

Hudson River to which their natural access was the Tappan

Creek.

But here again,

their way was not clear.

between them and the Hudson were,

Lockhart,

suddenly,

Standing

one Dr. George