Higher Education Physical Activity Programs: Past, Present, Future

advertisement

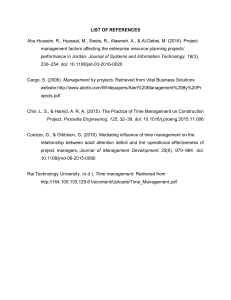

Quest ISSN: 0033-6297 (Print) 1543-2750 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uqst20 Teaching an Old Dog New Tricks: Past, Present, and Future Priorities For Higher Education Physical Activity Programs Drue T. Stapleton, Andrea R. Taliaferro & Sean M. Bulger To cite this article: Drue T. Stapleton, Andrea R. Taliaferro & Sean M. Bulger (2017) Teaching an Old Dog New Tricks: Past, Present, and Future Priorities For Higher Education Physical Activity Programs, Quest, 69:3, 401-418, DOI: 10.1080/00336297.2016.1256825 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1256825 Published online: 17 Jan 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 673 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 5 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=uqst20 QUEST 2017, VOL. 69, NO. 3, 401–418 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1256825 Teaching an Old Dog New Tricks: Past, Present, and Future Priorities For Higher Education Physical Activity Programs Drue T. Stapletona, Andrea R. Taliaferrob and Sean M. Bulgerc a Department of Biology, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Rider University, Lawrenceville, New Jersey; Department of Coaching and Teaching Studies, College of Physical Activity and Sport Sciences, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia; cCollege of Physical Activity and Sport Sciences, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia b ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Physical education programs in colleges/universities have been called on to provide students with opportunities to develop an appreciation for, and increase participation in, lifetime physical activity. Higher Education Physical Activity Programs (HEPAPs) have evolved over the past 100 years in response to changing societal and institutional expectations. The purpose of this article is to celebrate the long history of HEPAPs and recommend innovative strategies for program development that will maintain their position as a valued aspect of campus life. After tracing the historical roots and trends of HEPAPs, the authors suggest (a) adopting a public health perspective, (b) applying theoretical models as a framework for program development, (c) focusing on meaningful learner engagement, and (d) employing learner-centered instructional approaches. Within these overall themes, specific recommendations for program improvement are provided, including the use of alternative content areas, modelbased instruction, universal design, instructional technology, and professional development for faculty/staff. Basic instruction program; college/university physical education; higher education physical activity program “He muste teche his dogge to barke whan he wolde haue hym, to ronne whan he wold haue hym, and to leue ronning whan he wolde haue gym; or els he is not a cunninge shepeherd. The dogge must lerne it, whan he is a whelpe, or els it wyl not be: for it is harde to make an olde dogge to stoupe.” Quote from Fitzherbert’s Book of Husbandry (Skeat, 1882, p. 45) The previously referenced quote is thought to represent the origin of the widely used phrase “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks,” which describes how difficult it is for an individual to learn a novel approach when a person has been doing something a particular way for an extended period. The purpose of this article is to challenge that commonly held assumption by celebrating the long history of a very “old dog,” the college/university Basic Instruction Program (BIP) or Higher Education Physical Activity Program (HEPAP), and to recommend some “new tricks” that, if mastered, will help to maintain its position as a valued part of campus life. CONTACT Drue T. Stapleton dstapleton@rider.edu 2083 Lawrenceville Road, Lawrenceville, NJ 08648. College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Department of Biology, © 2017 National Association for Kinesiology in Higher Education (NAKHE) 402 D. T. STAPLETON ET AL. The mythology of dog years While tradition suggests that one “human” year equates to seven “dog” years, researchers in the veterinarian sciences have questioned the validity of this underlying assumption to learn that reality is more complicated, with a number of factors interacting to determine the actual life expectancy of “man’s best friend” (Crockett, 2014). Keeping with that analogy, a multitude of contextual variables have also contributed to the longevity of the HEPAP in its various configurations through the decades. While the clock had seemingly “run out” at several points in its long history, the HEPAP has proven to be remarkably adaptable and remains a fixture on many college and university campuses. In one form or another, the HEPAP has existed since the late 1800s, when faculty established the first physical education (PE) program at Amherst College in Massachusetts (Considine, 1985; Oxendine, 1985). The initial purpose of the HEPAP was to provide students with a coping mechanism to help “deal with the rigors of their academic work” (Lumpkin & Jenkins, 1993, p. 33). Through the use of European gymnastic elements, instructors attempted to increase strength, endurance, and the overall health of their students. The University of Pennsylvania became the first major institution of higher education to require PE for all students for four years as well as passing a swimming competency to graduate (Oxendine, 1985). World War I served as an influential force on required PE at the college level. Military leaders argued that low fitness levels diminished the ability of American men to serve and reduced their ability to survive “the hardships of a war” (Oxendine, 1985, p. 32). Consequently, the period from 1900–1930 observed an increase in the number of required programs. The overall emphasis of HEPAPs during this time was away from overall health and fitness, toward “psychomotor, character and intellectual objectives of the whole person” (Oxendine, 1985, p. 33). The time from 1930–1950 was marked by significant growth for HEPAPs (Hensley, 2000). Athletic departments and academic departments merged, PE’s role in general education was linked via educational objectives, and the HEPAP was again used as an avenue to develop fitness, strength, and endurance of future soldiers to prepare them for war. Following the conclusion of World War II, athletic departments separated from PE programs, primarily for financial reasons. An increased emphasis on the doctoral degree in PE contributed to the use of graduate assistants teaching within the HEPAP. Men’s programs were dominated by competitive team sports, while women’s programs focused on skill instruction and recreational activities (Hensley, 2000). The HEPAP of the 1960s and 1970s looked much more like today’s programs. Lifetime sports became popular, administrators relied on graduate teaching assistants (GTAs) for instruction, fewer coaches taught, and team sports orientation continued as competition among females gained increased acceptance. From 1970–1980, the overall number of institutions requiring PE decreased; students demanding new freedom and control over their educational experience forced remaining programs to shift curricular offerings toward fitness, outdoor activities, and lifetime sports (Trimble & Hensley, 1990). The overall purpose of the HEPAP again shifted from personal development to the development of lifetime skills and fitness. From 1980 until the 1990s, the emphasis continued to shift in response to changing societal beliefs toward the development and maintenance of fitness and the inherent value of participation in physical activity (PA) in any form throughout the lifespan. QUEST 403 “Health-related outcomes again became the primary purpose” (Oxendine, 1985, p. 36) of the HEPAP. Administratively, HEPAPs faced an upward trend of using GTAs, reduced faculty involvement, increased adjunct faculty usage, and increased budgetary pressure to be cost effective. Trimble and Hensley (1990) and Hensley (2000) investigated changes within the HEPAP, revealing consistent trends with earlier investigations. While it is likely that programmatic changes have continued to take place, limited research has focused on HEPAPs since Hensley (2000). A summary of the key points throughout the historical progression of HEPAPs and their associated references can be found in Table 1. Teaching an old dog new tricks Despite its advanced age and the widely held belief that “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks,” the authors contend that the HEPAP has demonstrated a capacity to reinvent itself to meet changing expectations in higher education. As the rate of change continues to escalate, HEPAP personnel find themselves in a competitive environment characterized by decreased public funding for colleges and universities, rising tuition costs and concerns with student retention, emphasis on student recruitment and enrollment management, and increased calls for accountability in higher education (Hemelt & Marcote, 2016; Lemoine, Hackett, & Richardson, 2016; Mitchell & Leachman, 2015; Pike & Robbins, 2016). Faced with these institutional challenges and the resultant on-campus competition for a limited pool of resources, it is critical that administrators learn some “new tricks” to better position the HEPAP as a sustainable component of the academic mission moving forward. These recommendations include (a) rebranding from a public health perspective, (b) use of the socio-ecological model as a conceptual framework, (c) innovation of course content, modes of delivery, and inclusive environments, and (d) renewed focus on learnercentered approaches. New trick 1: Rebranding from a public health perspective Healthy Campus 2010 (American College Health Association [ACHA], 2002) identified physical inactivity as one of the six priority health-risk behaviors requiring immediate action. Dinger (1999) reported that 50% of students fail to meet American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines for adequate PA. More recently, data from the ACHA (2011) National College Health Assessment—II indicate that 58% of college students reported no moderate or vigorous PA. Additional evidence highlighting the PA levels of college students indicates 48.3% did not meet ACSM and American Heart Association recommendations of 30 minutes of moderate PA on 5 or more days per week, or 20 minutes of vigorous PA on 3 or more days per week. A 15% decline in vigorous activity and 10% decline in moderate PA was seen from 18–19-year-old adults to 25–29year-old adults (Leslie, Sparling, & Owen, 2001). Gender differences in PA observed in other age populations are similar in college-aged individuals, with men reporting greater PA rates than women (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1996) and higher vigorous PA rates. However, the decline in vigorous PA is observed earlier in females (around age 12) than males (around age 14), with the lowest levels at age 21 for males and age 20 for females (Caspersen, Pereira, & Curran, 2000). 404 D. T. STAPLETON ET AL. Table 1. Summary of historical trends in HEPAP. Theme Graduation requirement Assessment Personnel and staffing Program purposes and outcomes Curricular offerings Summary Overall, from 1954 to 1972, percentages of institutions requiring PE for graduation remained fairly high (80–95%). Percentages decreased steadily until 1978, rising slightly until 1990, then decreasing at the start of the 21st century. Larger, public institutions more likely to eliminate PE requirement; smaller, private institutions more likely to maintain a requirement. There has been little change in assessment and grading procedures since inception. Letter grades or pass/fail dominate. Larger institutions more likely to utilize letter grading; smaller more likely to use pass/fail system. Smaller institutions likely to administer knowledge, fitness, and skill tests. Competency and proficiency testing more likely at larger institutions. Use of tenure track faculty teaching in HEPAPs initially reported at 42%, has declined steadily to date. Larger institutions report fewer tenure track faculty teaching, but higher percentages of non-tenure track faculty, adjuncts, activity specialists, or GTAs. Smaller institutions more likely to use coaches and dual role. Adjunct and activity specialists continue to rise as course offerings shift. Most commonly reported purposes: commitment to lifelong participation, fitness and health development, help students enjoy participation in PA. Outcome assessment focused on student perceptions, reasons for enrollment, and student evaluation. Outcome assessments revealed similar results: fitness development, enjoyment, and skill development. Students are satisfied with program/ coursework; course content and the instructor are significant influencing variables. Individual and team sports dominated curricula. Fitness oriented courses, outdoor adventure activities. Course offerings reflect student interest; team sports continue to decline. Multi-dimension CBFW courses have grown in use/popularity since 1990s. References Fornia, 1959; Green, 1955; Hensley, 2000; Hunsicker, 1954; Miller, Dowell, & Pender, 1989; Oxendine, 1961, 1969, 1972; Oxendine & Roberts, 1978; Trimble & Hensley, 1984, 1990 DeKnop, 1986; Hensley, 2000; Hunsicker, 1954; Miller et al., 1989; Poole, 1993; Oxendine, 1961, 1969, 1972; Trimble & Hensley, 1984, 1990 Evaul & Hilsendanger, 1993; Hensley, 2000; Miller et al., 1989; Oxendine, 1969; Oxendine & Roberts, 1978; Russel, 2008a; Trimble & Hensley, 1984 Boyce, Lehr, & Baumgartner, 1986; Crawford, Greenwell, & Andrew, 2007; Hardin, Andrew, Koo, & Bemiller, 2009, Hensley, 2000; Kisabeth, 1986; Lumpkin & Avery, 1986; Russell, 2008b; Savage, 1998; Trimble & Hensley, 1990 Hensley, 2000; Hunsicker, 1954; Miller et al., 1989; Oxendine, 1961, 1969, 1972; Oxendine & Roberts, 1978; Trimble & Hensley, 1984, 1990 Public health perspective These findings regarding college student PA levels support that this issue represents both an immediate and long-term public health concern because behaviors established during the college years have been shown to persist into adulthood (Sparling & Snow, 2002). Related concerns regarding school-aged populations have prompted a major paradigm shift focused on childhood and adolescent PA and the benefits from a public QUEST 405 health perspective as the primary focus of preK–12 PE programs (Sallis & McKenzie, 1991; Sallis et al., 2012). As recommended by Sallis and McKenzie (1991), healthoriented (or health-optimizing) PE (HOPE) focuses on the overarching public health goal of facilitating development of the knowledge, behavioral capabilities and skills, and dispositions needed for optimal health benefits and to remain physically active across the lifespan (Metzler, McKenzie, van der Mars, Barrett-Williams, & Ellis, 2013a). The HOPE curriculum challenges physical educators and PA specialists to provide opportunities to engage in developmentally and instructionally appropriate forms of PA before, during, and after school through increased content expertise and engagement of school personnel, families, and community-based organizations (Metzler, McKenzie, van der Mars, Barrett-Williams, & Ellis, 2013b; Webster et al., 2015). HEPAP rebranding efforts These vital educational goals apply to college-aged learners as well. It follows that department and executive-level administrators may need to collaborate to identify opportunities to rebrand HEPAPs through this lens as an approach to increasing student enrollment in the program, maintaining visibility on campus, and program justification. These rebranding efforts should focus on the signature features of the involved HEPAP, including its value from a public health perspective. A first step in any rebranding effort involves time spent reflecting on the unique selling points of the particular program and responding to main questions like “Who are we?” and “What do we do best?” (Teichler, 2003; Veloutsou, Lewis, & Paton, 2004). The answers to these questions may reflect the historical traditions of the HEPAP and/or institution. Alternatively, the results may indicate a need to eliminate or reduce program offerings based on multiple variables. Regardless of the outcomes of the assessment, the results are likely to vary considerably based on Carnegie Classification, which accounts for various institutional demographics like type, size and setting, and enrollment profile. As a second step, administrators should develop plans for strategic communication targeting internal and external key stakeholders. The related key messaging should emphasize the program’s unique mission, vision, values, and signature features (Gray, 2003; Teichler, 2003). Internal stakeholders include current university students, faculty/researchers, staff, and administrators across a range of academic and administrative units as potential participants, collaborators, or supporters. External stakeholders include prospective students and their families, alumni, potential community partners, and policy decision-makers who might also be able to contribute in different capacities. It is critical, however, that this key messaging also find its way into all aspects of HEPAP planning, implementation, management, and evaluation. Therefore, the final step of the rebranding process focuses on the personalization of the new brand through all service transactions, person-to-person interactions, teaching–learning processes, and educational experiences associated with the particular academic program (Gupta & Singh, 2010). This degree of personalization is likely to require a significant investment in staff training and continuing professional development. 406 D. T. STAPLETON ET AL. New trick 2: Using socio-ecological model as a program framework As reflected in the previously described steps for program rebranding, it is critical that HEPAP administrators understand how their programs and respective course offerings fit within the broader ecology of the campus community. Furthermore, a common criticism of physical activity intervention research across settings remains the limited use of sound theoretical models in facilitating health-related behavior change. One conceptual framework that is appropriate for use in colleges and universities is the social ecological model. While certain theoretical models address only personal determinants, and other models only environmental determinants, the social ecological model addresses determinants and barriers of PA from multiple levels, making it appropriate for discussion concerning promotion and the influence of the HEPAP on college student PA. Social ecological model The social ecological model focuses on “the nature of people’s transactions with their physical and sociocultural surroundings” (Stokols, 1992, p. 7). The model suggests multiple levels of interaction of behaviors and behavior settings, the “social and physical situations in which behaviors take place” (Sallis & Owen, 2002, p. 463). The model has its roots in the work of Brofenbrenner (1979), who viewed behavior as being influenced by both individual and environmental determinants. McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, and Glanz (1988) expanded on Brofenbrenner’s model, providing more in-depth analysis, suggesting that patterned behavior is the focus, and that behavior influences and is impacted by five factors: (a) intrapersonal factors, (b) interpersonal factors, (c) institutional factors, (d) community factors, and (e) public policy (McLeroy et al., 1988). Ecological approaches have been suggested to “provide environmental resources and interventions that promote enhanced well-being among occupants of an area” (Stokols, 1992, p. 6). The five core principles of the social ecological perspective emphasize the role of the environment and personal attributes on health behaviors, the relationships between and among layers, the interaction between people and their environments, and the interdependence and interconnectedness “between multiple setting and life domains” (Stokols, 1996, p. 286). The final core principle stresses the “inherently interdisciplinary” approach (p. 286), providing the opportunity for integration of public health and epidemiological prevention strategies, individual-level strategies of the medical model, and community-wide interventions (Stokols, 1996). Multi-component approaches In order to maximize their potential from a public health perspective, curriculum organizers would be well-advised to consider the implications of these core principles for HEPAP development and implementation. Current calls for whole-of-school or comprehensive school physical activity programs in preK–12 settings highlight the critical role of educational settings as an intersection point for multiple behavioral influences (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Institute of Medicine, 2013; Society of Health and Physical Educators, 2013). There is an emerging body of evidence supporting the use of multi-component approaches for the promotion of physical activity in PreK–12 schools (Erwin, Beighle, Carson, & Castelli, 2013; McMullen, Ní Chróinín, Tammelin, Pogorzelska, & van der Mars, 2015), and these findings have relevance for HEPAPs. QUEST 407 As an environment for PA promotion, HEPAPs often afford PA promotion specialists a number of advantages, including ready access to students, spaces and equipment, qualified staff, supportive policies, transportation to and from, and multiple settings for intervention before, during, and after regular school hours (Pate et al., 2006). It is critical that instructional personnel look beyond the intrapersonal and interpersonal determinants of behavior that are readily evident within PA courses to reconceptualize HEPAPs across all levels of influence. Societal influences, such as political decisions, policy development, and cultural shifts or movements, influence and may be affected by HEPAPs (Wang, Castelli, Liu, Bian, & Tan, 2010). For example, by enacting and/or enforcing an existent policy (e.g., sidewalk maintenance, bicycle lanes, and/or helmet laws), engaging local community contacts as guest instructors or lecturers, lobbying for and developing new policies on campus, through faculty governance, and/or off campus legislative efforts, HEPAP professionals can advocate for health-based initiatives and policies specifically related to PA. Furthermore, HEPAP leaders have an opportunity to expand these advocacy efforts by engaging community members and stakeholders in educational opportunities and collaborating to develop strategies to promote PA on the community level. Allowing non-students (i.e., community members, faculty, staff, etc.) to participate in HEPAP courses may provide an opportunity for the HEPAP to share information, develop skills, and increase awareness of the negative health outcomes associated with physical inactivity. Forming alliances with public health agencies, public health professionals, and other medical professionals (i.e., the American College of Sports Medicine’s Exercise is Medicine program) may also provide additional opportunities for HEPAPs to influence cultural and societal norms. Expanding offerings and exposure to student recreation departments/centers, outdoor recreation and wilderness centers, student health and wellness centers, and community venues may provide access to additional PA opportunities for students to develop skills and supportive relationships. The development of new or enhancement of existing relationships with other wellness-oriented programs on and off campus could result in the mutually beneficial sharing of resources. New trick 3: Moving past introducing, informing, and entertaining Kretchmar (2006) argued that the effectiveness of school-based PE is limited by the tendency for practitioners to take the path of least resistance by focusing on introducing, informing, and entertaining. Rather than inviting students to experience the richness of its disciplinary content, PE rarely provides the types of challenging experiences that facilitate the level of learning and competence development needed for the individual to make more permanent lifestyle changes. This criticism is easily extended to college and university PE programs that are also characterized by a custodial orientation at times. Custodial orientations reflect a focus on maintenance of the status quo through dependence on traditional approaches to teaching PE (McPhail & Hartley, 2016). By contrast, HEPAPs are advised to demonstrate a more innovative orientation that “reflects an individual or context that is open to change and encourages new approaches to teaching physical education” (p. 170). MacPhail and Hartley (2016) proposed that innovation in teaching settings is facilitated through the use of new teaching methods, action research, reflective practice, and change agency. A number of the recommendations for program innovation 408 D. T. STAPLETON ET AL. in the following subsections are adopted from the literature on school-based PE, and it is important to note that their applicability to HEPAPs is somewhat dependent on context. Course content Team sports continue to dominate the PE curriculum; however, the most popular activities among adults are mostly individual and non-competitive in nature (Ham, Kruger, & Tudor-Locke, 2009). Rather than an exclusive focus on traditional sports, HEPAPs must continue to adapt to current trends by applying the concept of “cool PE.” The term “cool PE” refers to those activities that “move” and provide ownership to students, giving those who are not well-served by current PE approaches’ reasons to participate (McCaughtry, 2009). As opposed to the “uncool” team-sports orientation that favors the skilled and fit and sometimes lacks focus on meaningful engagement, “cool PE” activities deliver personally relevant content to students and mirror current trends, allowing students to explore a wider variety of options. Considering that HEPAPs are often the most visible component of PE departments on college campuses, it is important that instructors don’t perpetuate the “typical PE” that individuals may not fondly recall from their PreK– 12 years and instead identify trends to engage students in activities that have personal relevance, increase positive perspectives, and promote health-enhancing levels of PA. Student voices obtained through formal and informal needs assessment processes like student interest questionnaires, focus groups, and course completer surveys can prove helpful when making these types of curricular decisions. Examples of “cool PE” activities might include yoga, orienteering, martial arts, Pilates, strength and conditioning, stand-up paddle boarding, paddleboard yoga, archery tag, and triathlons, and may also focus on activities that are geographically and culturally relevant. With respect to the issue of geographical and cultural relevance, administrators and instructors must demonstrate some measure of intentionality in aligning their course offerings with the other recreational opportunities available on campus and in the surrounding community/region. A high degree of alignment can result in enhanced opportunities for the shared use of facilities and equipment, greater continuum of services and programs across a developmental perspective, and increased likelihood of transference of learned behaviors from university-based to community-based programs. Community asset mapping is an alternative information-gathering approach that HEPAP developers can use to identify the complementary resources available on campus and in the surrounding area that present opportunities for university–community partnership: local residents with related skills (including family members), experiences, and interests; local voluntary associations, clubs, and networks which could contribute to the project; local public and private institutions with a related mission; physical assets like parks and recreation facilities; and economic resources, including potential business partners (Kretzmann, McKnight, Dobrowolski, & Puntenney, 2005). Asset mapping is an inherently flexible process that uses a participatory framework and involves a combination of information collection approaches including windshield/walking tours of communities, key stakeholder interviews, focus group discussions, resource inventories, and so forth (Baker et al., 2007; Dorfman, 1998; Goldman & Schmalz, 2005). Engaging in asset mapping may serve a twofold objective: aligning HEPAP offerings with communities and reducing barriers to PA by QUEST 409 highlighting community resources/access, providing opportunities for social support, and increasing individual skill level and confidence. Models of delivery The previous recommendations regarding the selection of course content should not be misinterpreted as a call to remove competitive team and individual sports from college and university PE programs entirely. Those competitive forms of movement continue to resonate with many college-aged learners, as supported by the popularity of intercollegiate, intramural, and extramural club sports on many college and university campuses. Course instructors in both traditional and non-traditional content areas should be challenged, however, to consider the use of research-supported pedagogical models to better engage learners across levels of readiness and proficiency (beginning, intermediate, and advanced). As in the past, HEPAPs must continue to evolve and explore new ways of delivering content focused on learning and skill competence. Once such consideration would be moving away from the traditional teacher-focused models of instruction in favor of more learner-focused orientations that have been proven effective in the PE setting. These models might include, but are not limited to, the Sport Education Model and Teaching Games for Understanding (TGFU). The Sport Education Model was developed with the intent of providing developmentally appropriate sport experiences so that students can develop as competent, literate, and enthusiastic sportspersons (Siedentop, Hastie, & van der Mars, 2011). In one version of this model, students rotate through diverse roles during the sport season, including coach, captain, scorekeeper, statistician, publicist, fitness trainer, equipment manager, sport-council member, and broadcaster. The Sport Education Model has been found to be one of the most frequently used curriculum and instruction models in undergraduate PETE programs in the United States (Ayers & Housner, 2008) and has been recommended as a potential curricular model in HEPAP to promote inclusive and developmentally appropriate PA (Braga, Tracy, & Taliaferro, 2015). The concept of TGFU is an approach in which games are classified by similar conditions, goals, and tactics. This approach focuses on developing an understanding of the concepts and emphasizes the tactics central to similar games, enabling learners to transfer this understanding among games within the same conceptual category while developing a repertoire of strategies which may be useful in games in other categories (Kirk & MacPhail, 2002). While these models of instruction have been researched in the PreK– 12 PE setting, there have been relatively few studies on their effectiveness in HEPAP settings. Limited research on the Sport Education Model in the university setting found that students were favorable to the Sport Education Model and made progress regarding course objectives (Mohr, Sibley, & Townsend, 2012). Similarly, Layne and Yli-Piipari (2015) found that the use of the Sport Education Model in a university PA course was more effective in teaching offensive game performance and content knowledge than a traditional model of teaching, suggesting the Sport Education Model as an effective pedagogical approach in HEPAPs. Inclusive approaches Furthermore, HEPAPs must expand and address the audience of diverse learners whose individualized needs and interests have not been met to date by existing models. 410 D. T. STAPLETON ET AL. Considering the increase in the numbers of students with disabilities pursuing higher education (Barfield, Bennett, Folio, & Killman, 2007), progress is needed to establish appropriate support, services, and accommodations for students with disabilities within HEPAP courses (Braga et al., 2015; Higbee, Katz, & Schultz, 2010; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2010). Students with disabilities have traditionally faced barriers, including inaccessible facilities and equipment, inadequately trained personnel/instructors, and inadequate or non-compliant programs and curricula that limit their participation (Braga et al., 2015; Russell, 2011; Russell & Chepyator-Thomson, 2004; U.S. Department of Education, 2011). Following similar patterns to individuals without disabilities, 56% of individuals with disabilities are sedentary and do not participate in the recommended levels of PA per week (Lakowski & Long, 2011; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). HEPAPs may be best positioned to provide appropriate opportunities for students of all ability levels, including those with disabilities, to participate in and meet recommended levels of PA. Suggestions to increase opportunities within HEPAPs include consideration of accessibility, principles of universal design, provision of appropriate equipment (modified or specialized if necessary), support personnel, inclusive teaching styles, program options, and modifications to assessments and grading policies as needed. Expanding HEPAP offerings to include disability sport or adapted sport options, such as wheelchair basketball, goalball, or beep baseball, could meet the differentiated needs of students with disabilities and could also expand the knowledge and skill base of participants without disabilities who enroll in these courses. Also, allied or unified sport opportunities, in which students with and without disabilities participate on teams together, could be explored, further promoting inclusive PA opportunities. New trick 4: Learner-centered approaches As with any educational setting, student learning needs to remain the primary focus of HEPAP personnel. This recommendation includes the use of alternative course structures, instructional technologies, and evidence-based practice related to HEPAP administration and instruction. Concepts-based courses In concepts based fitness and wellness (CBFW) courses that are offered by higher education institutions (Hodges-Kulinna, Warfield, Jonaitis, Dean, & Corbin, 2009), conceptual information related to health, wellness, fitness, behavior change strategies, and self-management skills are developed in the lecture component, and engagement in a variety of activities is emphasized in the PA laboratory. These types of HEPAP offerings have showed positive impacts on college students’ health-related behaviors and habits, knowledge, and attitude toward fitness and PA (Adams & Brynteson, 1995; Beck et al., 2007; Brynteson & Adams, 1993; Cardinal & Spaziani, 2007; Pearman et al., 1997; Slava, Laurie, & Corbin, 1984; Sparling, 2003) compared to traditional sport-based offerings. The longterm impact of CBFW courses has yet to be explored; however, the combination of increased CBFW offerings and the ability of CBFW courses to have a significant impact on knowledge and attitude toward and increased PA levels suggests that CBFW courses QUEST 411 may play a meaningful role in the transition of HEPAPs to promote PA and serve college students’ needs (Corbin & Cardinal, 2008). Given the push for health-optimizing, PA centered approaches in HEPAPs, the current practice of devoting a large percentage of classroom time to lecture in some concepts-based courses, thereby reducing the time available for activity participation, is questionable. Moving forward, CBFW course instructors might consider how to maximize opportunities for PA through instructional technologies and inventive teaching approaches. The flipped classroom approach, in which “events that have traditionally taken place inside the classroom now take place outside the classroom and vice versa” (Lage, Platt, & Treglia, 2000, p. 32), might be ideal in CBFW courses. The flipped approach can be used to enhance or replace face-to-face lectures and might employ online asynchronous video lectures, interactive lectures, videos, online assignments, readings, discussions, and/or exams completed by students outside of class time, freeing up class time for structured group activity. This is not to say the flipped approach would benefit only CBFW courses; other pedagogical models, such as the Sport Education Model or TGFU, may benefit from flipping for teaching rules, concepts, and historical background. Instructional technology application Additionally, rapidly developing instructional technology options, including a variety of PA measurement technologies, continue to become a more affordable and accessible means for tracking student activity levels (e.g., digital pedometers, accelerometers, heart rate monitors). Greater application of these types of technology within HEPAP offerings would better enable instructors to assess student activity and track their achievements (Stapleton & Bulger, 2015). These technologies allow instructors to track asynchronous activity participation in online or blended course options. Exploring the use of web-based technologies, fitness applications, and other technologies enables instructors to expand beyond in-person meetings and would allow students to engage in learner-centered, selfpaced PA within their environments. A related recommendation includes the use of electronic learning management systems (LMS) to promote improved teaching effectiveness within HEPAPs through increased instructor training capability, student assessment, and program evaluation (Melton & Burdette, 2011). Use of evidence-based practice Researchers have called for further program evaluation of college/university PE to provide better evidence supporting its impact on health-related behaviors (Evaul & Hilsendanger, 1993; Housner, 1993; Leslie et al., 2001; Lumpkin & Avery, 1986; Sparling, 2003; Stapleton & Bulger, 2015; Sweeney, 2011). Evidence-based practice (EBP) involves the integration of the best available evidence from research, the expertise of the clinician (or in this case instructor), and the values of the patient or learner (Sackett, Rosenburg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, 1996). In 2000, it was estimated that only 15–40% of clinical decisions by physicians were based on research evidence, leading to a call for reform (Amonette, English, & Ottenbacher, 2012). The emphasis on adoption of an evidence-based approach has since spread to a number of allied health professions, including athletic training, nursing, physical therapy, exercise physiology, and now PE. At the present time, it does 412 D. T. STAPLETON ET AL. Table 2. Summary of recommendations for HEPAP. Theme Recommendations Rebranding from a public health perspective Adopt important public health goals as program focus: (1) facilitating development of the knowledge, behavioral capabilities and skills, and dispositions needed to remain physically active across the lifespan, and (2) providing opportunities to engage in developmentally and instructionally appropriate forms of PA. Rebrand programs using a structured process: (1) reflect on unique program selling points as basis for rebranding, (2) develop plans for communicating with key internal and external stakeholders, and (3) work to make new brand evident in all program processes and client interactions. Using the socioecological model Use of an ecological framework for program development, implementation, management, and evaluation. Employ multi-component approaches to physical activity promotion on colleges and university campuses. Coordinate programming with other groups or organizations on campus and in the surrounding community. Advocate for policy initiatives on campus and off campus that support healthbased initiatives. Moving past introducing, informing, Continue to diversify course offerings to include “cool” and alternative forms of and entertaining physical activity. Engage college-aged learners in the needs assessment and curriculum development process. Use evidence-based instructional models to actively engage learners in different content areas. Apply principals of universal design to meet the unique needs of all learners in all courses. Expand course offerings to include a variety of disability sport or adapted sport options. Conduct periodic asset mapping efforts to determine opportunities for community partnership. Align course offerings with the recreational activities available in the surrounding community and region. Establish shared-use agreements with other providers to increase access to equipment and facilities. Promote transference of learned behaviors from campus to community-based settings and programs. Learner-centered approaches Demonstrate the effectiveness of concepts-based courses and continue to refine modes of delivery. Use emerging technologies to implement flipped learning experiences and maximize in-class activity. Explore application of activity monitors and related technologies during in-class and out-of-class activities. Provide better in-service training, instructional supervision, and continuing professional development for program personnel, graduate assistants, and adjunct faculty. Increase use of evidence-based approaches to increase program effectiveness and document impact on learner activity levels, physical fitness, health, and quality of life. not appear that evidence-based approaches are being employed within HEPAPs on a larger scale. The balance, integration, and continual re-evaluation of existing research, the experience of the administrators and faculty, and the values of the students provide a framework for the implementation of evidence-based PE (EBPE). Knowledge of the existing literature investigating HEPAPs and effective PE, what motivates college students and how they learn, the impact of HEPAP offerings on the individuals and environmental variables (and vice versa), and the experience of the instructor and/or administrator must be considered in EBPE. Furthermore, HEPAP administrators and instructors are advised to invest QUEST 413 sufficient resources in the assessment of student learning and program evaluation as a basis for data-informed decision making. The gap between the recommendations for best practice in assessment/evaluation and actual implementation remains a long-standing concern that may contribute to the lack of teaching effectiveness observed in HEPAPs (Housner, 1993; Stapleton & Bulger, 2015). This perceived gap also reinforces the need for adequate in-service training, instructional supervision, and continuing professional development for HEPAP personnel. The adoption of EBPE requires HEPAP personnel to reflect on their experience(s) and education, the established body of knowledge, and the values of the students in order to inform future practices and development of HEPAPs. Decision-making, policy formulation, the training of instructors, and course offerings should be examined from an evidence-based perspective to maximize the potential influence on PA behavior. The HEPAP personnel engaging in EBPE are likely to enhance their programs while simultaneously reducing the barriers to activity among college students, thereby increasing their ability to adapt to the needs of their learners, institutions, and society. Summary Historically, HEPAPs have demonstrated the capacity to transform themselves when confronted with changing institutional expectations. On many college/university campuses, HEPAPs continue to engage large numbers of young adults, an important target group for PA promotion efforts from a public health perspective. Faced with this emerging challenge, HEPAP leaders must continue to evolve their programs and prove their value to the academic communities they serve. Those programs that are responsive and capable of learning a few “new tricks” will generate new opportunities and quite possibly contribute to the more ambitious goal of healthier campuses and communities. Those “old dogs” who are too tired to change or adopt new approaches may just “roll over and play dead.” The HEPAP represents one of the final opportunities to directly influence the perceptions of young adults, who will become our next generation of parents, teachers, school administrators and board members, and policy-makers, regarding the benefits associated with a quality PE experience. The recommendations provided in this article are summarized in Table 2 and are expected to provide HEPAP personnel with some ideas to facilitate discussions about the past, present, and future priorities for this very visible and important component of our college and university programs. References Adams, T. M., & Brynteson, P. (1995). The effects of two types of required physical education. The Physical Educator, 52, 203–211. American College Health Association [ACHA]. (2002). Healthy campus 2010: manual. Baltimore, MD: Author. American College Health Association [ACHA]. (2011). American College Health Association— National College Health Assessment II: Reference group executive summary spring 2011. Hanover, MD: Author. Amonette, W. E., English, K. L., & Ottenbacher, K. J. (2012). Nullius in verba: A call for the incorporation of evidence-based practice into the discipline of exercise science. Sports Medicine, 40, 449–457. doi:10.2165/11531970-000000000-00000 414 D. T. STAPLETON ET AL. Ayers, S. F., & Housner, L. D. (2008). A descriptive analysis of undergraduate PETE programs. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 27(1), 51–67. doi:10.1123/jtpe.27.1.51 Baker, I. R., Dennison, B. A., Boyer, P. S., Sellers, K. F., Russo, T. J., & Sherwood, N. A. (2007). An asset-based community initiative to reduce television viewing in New York state. Preventive Medicine, 44, 437–441. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.11.013 Barfield, J. P., Bennett, J., Folio, M. R., & Killman, C. (2007). Disability rights in higher education: Ensuring kinesiology program and accreditation standards do not discriminate. Quest, 59, 384– 397. doi:10.1080/00336297.2007.10483560 Beck, J., Collins, M., Goldfine, B., Barros, M., Nahas, M., & Lanier, A. (2007). Effect of a required health-related fitness course on physical activity. International Journal of Fitness, 3(1), 69–80. Boyce, B. A., Lehr, C., & Baumgartner, T. (1986). Outcomes of selected physical education activity courses as perceived by university students. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 5, 280– 292. doi:10.1123/jtpe.5.4.280 Braga, L., Tracy, J., & Taliaferro, A. R. (2015). Physical activity programs in higher education: Modifying net/wall games to include individuals with disabilities. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 86(1), 16–22. doi:10.1080/07303084.2014.978417 Brofenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Brynteson, P., & Adams, T. M. (1993). The effects of conceptually based physical education programs on attitudes and exercise habits of college alumni after 2 to 11 years of follow up. Research Quarterly For Exercise & Sport, 64, 208–212. doi:10.1080/02701367.1993.10608798 Cardinal, B. J., & Spaziani, M. D. (2007). Effects of classroom and virtual “Lifetime Fitness for Health” instruction on college students’ exercise behavior. The Physical Educator, 64, 205– 212. Caspersen, C. J., Pereira, M. A., & Curran, K. M. (2000). Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 32, 1601– 1609. doi:10.1097/00005768-200009000-00013 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2013). Comprehensive school physical activity programs: A guide for schools. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Considine, W. J. (1985). Basic instruction programs: A continuing journey. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 56(7), 31–31. doi:10.1080/07303084.1985.10604268 Corbin, C. B., & Cardinal, B. J. (2008). Conceptual physical education: The anatomy of an innovation. Quest, 60, 467–487. doi:10.1080/00336297.2008.10483593 Crawford, S. Z., Greenwell, T. C., & Andrew, D. P. (2007). Exploring the relationship between perceptions of quality in basic instruction programs and repeat participation. Physical Educator, 64(2), 65–73. Crockett, Z. (2014, October 1). The mythology of dog years [Web log post]. Retrieved from http:// priceonomics.com/the-mythology-of-dog-years/ DeKnop, P. (1986). Relationship of specified instructional teacher behaviors to student gain on tennis. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 5, 71–78. doi:10.1123/jtpe.5.2.71 Dinger, M. K. (1999). Physical activity and dietary intake among college students. American Journal of Health Studies, 15(3), 139–148. Dorfman, D. (1998). Mapping community assets workbook. In Strengthening community education: The basis for sustainable renewal. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct= true&db=eric&AN=ED426499&site=ehost-live Erwin, H., Beighle, A., Carson, R. L., & Castelli, D. M. (2013). Comprehensive school-based physical activity promotion: A review. Quest, 65, 412–428. doi:10.1080/00336297.2013.791872 Evaul, T., & Hilsendanger, D. (1993). Basic instruction programs: Issues and answers. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, & Dance, 64(6), 37–40. doi:10.1080/07303084.1993.10610000 Fornia, D. L. (1959). Coedcuational physical education in institutions of higher learning. The Research Quarterly of the American Association for Health, Physical Education, & Recreation, 30, 423–429. Goldman, K. D., & Schmalz, K. J. (2005). Tools of the trade. “Accentuate the positive!” Using an assetmapping tool as part of a community-health needs assessment. Health Promotion Practice, 6(2), 125–128. doi:10.1177/1524839904273344 QUEST 415 Gray, B. J. (2003). Branding universities in Asian markets. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 12(2), 108–120. doi:10.1108/10610420310469797 Greene, M. M. (1955). Physical education as a college graduation requirement. Journal of Health, Physical Education, & Recreation, 26(9), 25–26. Gupta, M., & Singh, P. B. (2010). Marketing and branding in higher education: Issues and challenges. Review of Business Research, 10(1). Retrieved from http://www.freepatentsonline. com/article/Review-Business-Research/237533606.html Ham, S. A., Kruger, J., & Tudor-Locke, C. (2009). Participation by US adults in sports, exercise, and recreational physical activities. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 6(1), 6–14. doi:10.1123/ jpah.6.1.6 Hardin, R., Andrew, D. P., Koo, G., & Bemiller, J. (2009). Motivational factors for participating in basic instruction programs. The Physical Educator, 66(2), 71–85. Hemelt, S. W., & Marcotte, D. E. (2016). The changing landscape of tuition and enrollment in American public higher education. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(1), 42–68. doi:10.1353/rus.2016.0002 Hensley, L. D. (2000). Current status of basic instruction programs in physical education at American colleges and universities. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, & Dance, 71(9), 30–36. doi:10.1080/07303084.2000.10605719 Higbee, J. L., Katz, R. E., & Schultz, J. L. (2010). Disability in higher education: Redefining mainstreaming. Journal of Diversity Management, 5(2), 7–16. Hodges-Kulinna, P., Warfield, W. W., Jonaitis, S., Dean, M., & Corbin, C. (2009). The progression and characteristics of conceptually based fitness/wellness courses at American universities and colleges. Journal of American College Health, 58(2), 127–131. doi:10.1080/07448480903221327 Housner, L. D. (1993). Research in basic instruction programs. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 64(6), 53–61. doi:10.1080/07303084.1993.10610004 Hunsicker, P. A. (1954). A survey of service physical education programs in American colleges and universities. Annual Proceedings of the College Physical Education Association, 57, 29–30. Institute of Medicine. (2013). Educating the student body: Taking physical activity and physical education to school. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Kirk, D., & MacPhail, A. (2002). Teaching games for understanding and situated learning: Rethinking the Bunker-Thorpe model. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 21, 177–192. doi:10.1123/jtpe.21.2.177 Kisabeth, K. L. (1986). Basic instruction programs: A search for personal meaning. The Physical Educator, 43, 150–154. Kretchmar, R. S. (2006). Life on easy street: The persistent need for embodied hopes and down-toearth games. Quest, 58, 344–354. doi:10.1080/00336297.2006.10491888 Kretzmann, J. P., McKnight, J., Dobrowolski, S., & Puntenney, D. (2005). Discovering community power: A guide to mobilizing local assets and your organization’s capacity. Asset-Based Community Development Institute, School of Education and Social Policy, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL. Lage, M. J., Platt, G. J., & Treglia, M. (2000). Inverting the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. The Journal of Economic Education, 31(1), 30–43. doi:10.1080/ 00220480009596759 Lakowski, T., & Long, T. (2011). Proceedings: Physical Activity and Sport for People with Disabilities. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. Layne, T. E., & Yli-Piipari, S. (2015). Effects of the sport education model on university students’ game performance and content knowledge in basketball. Journal of Sports Research, 2(2), 24–36. doi:10.18488/journal.90 Lemoine, P. A., Hackett, T., & Richardson, M. D. (2016). Higher education at a crossroads: Accountability, globalism and technology. In W. Nuninger & J.-M. Châtelet (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Quality Assurance and Value Management in Higher Education (pp. 27–57). Hershey, PA: IGI Global. 416 D. T. STAPLETON ET AL. Leslie, E., Sparling, P. B., & Owen, N. (2001). University campus settings and the promotion of physical activity in young adults: Lessons from research in Australia and the USA. Health Education, 101(3), 116–125. doi:10.1108/09654280110387880 Lumpkin, A., & Avery, M. (1986). Physical education activity program survey. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 5, 185–197. doi:10.1123/jtpe.5.3.185 Lumpkin, A., & Jenkins, J. (1993). Basic instruction programs: A brief history. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 64(6), 33–36. doi:10.1080/07303084.1993.10609999 MacPhail, A., & Hartley, T. (2016). Linking teacher socialization research with a PETE program: Insights from beginning and experienced teachers. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35, 169–180. doi:10.1123/jtpe.2014-0179 McCaughtry, N. (2009). The child and the curriculum: Implications of Deweyan philosophy in the pursuit of “cool” physical education for children. In L. Housner, M. Metzler, P. Schempp, & T. Templin (Eds.), Historic traditions and future directions of research on teaching and teacher education. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology, West Virginia University. McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education & Behavior, 15, 351–377. doi:10.1177/ 109019818801500401 McMullen, J., Ní Chróinín, D., Tammelin, T., Pogorzelska, M., & van der Mars, H. (2015). International approaches to whole-of-school physical activity promotion. Quest, 67, 384–399. doi:10.1080/00336297.2015.1082920 Melton, B., & Burdette, T. (2011). Utilizing Technology to Improve the Administration of Instructional Physical Activity Programs in Higher Education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 82(4), 27–32. doi:10.1080/07303084.2011.10598611 Metzler, M. W., McKenzie, T. L., van der Mars, H., Barrett-Williams, S. L., & Ellis, R. (2013a). Health OPTIMIZING PHYSICAL EDUCATION (HOPE): A new curriculum for school programs—Part 1: Establishing the need and describing the model. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 84(4), 41–47. doi:10.1080/07303084.2013.773826 Metzler, M. W., McKenzie, T. L., van der Mars, H., Barrett-Williams, S. L., & Ellis, R. (2013b). Health optimizing physical education (HOPE): A new curriculum for school programs—Part 2: Teacher knowledge and collaboration. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 84(5), 25–34. doi:10.1080/07303084.2013.779531 Miller, G. A., Dowell, L. J., & Pender, R. H. (1989). Physical activity programs in colleges and universities: A status report. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, & Dance, 60(6), 20–23. doi:10.1080/07303084.1989.10604474 Mitchell, M., & Leachman, M. (2015). Years of cuts threaten to put college out of reach for more students. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Mohr, D., Sibley, B., & Townsend, J. (2012). Student perceptions of university physical activity instruction courses taught utilizing sport education. Physical Educator, 69, 289–307. Oxendine, J. B. (1961). The service program in 1960–1961. Journal of Health, Physical Education, & Recreation, 32(6), 37–38. Oxendine, J. B. (1969). Status of required physical education programs in colleges and universities. Journal of Health, Physical Education, & Recreation, 40(1), 32–35. Oxendine, J. B. (1972). Status of general instruction programs of physical education in four-year colleges and universities: 1971–72. Journal of Health, Physical Education, & Recreation, 43(3), 26–28. Oxendine, J. B. (1985). 100 years of basic instruction. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, & Dance, 56(7), 32–36. doi:10.1080/07303084.1985.10604269 Oxendine, J. B., & Roberts, J. E. (1978). The general instruction program in physical education at four-year colleges and universities: 1977. Journal of Physical Education & Recreation, 49(1), 21– 23. Pate, R. R., Davis, M. G., Robinson, T. N., Stone, E. J., McKenzie, T. L., & Young, J. C. (2006). Promoting physical activity in children and youth: A leadership role for schools [AHA Scientific Statement]. Circulation, 114, 1214–1224. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177052 QUEST 417 Pearman, S. N., Valois, R. F., Sargent, R. G., Saunders, R. P., Drane, J. W., & Macera, C. A. (1997). The impact of a required college health and physical education course on the health status of alumni. Journal of American College Health, 46(2), 77–85. doi:10.1080/07448489709595591 Pike, G. R., & Robbins, K. (2016). The relationships among individual characteristics, high school characteristics, and college enrollment: Using enrollment propensity as a baseline for evaluating strategic enrollment management efforts. Strategic Enrollment Management Quarterly, 3, 282– 304. doi:10.1002/sem3.20075 Poole, J. R. (1993). The search for effective teaching in basic instruction programs. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, & Dance, 64(6), 41–58. doi:10.1080/07303084.1993.10610001 Russell, J., & Chepyator-Thomson, J. R. (2004). Help wanted! Perspectives of physical education graduate teaching assistants on their instructional environment, preparation and needs. The Educational Research Journal, 19, 251–280. Russell, J. A. (2008a). An examination of kinesiology GTAs’ perceptions of an instructional development and evaluation model. The Physical Educator, 65(1), 2–20. Russell, J. A. (2008b). Utilizing qualitative feedback to investigate student perceptions of a basic instruction program. The Physical Educator, 65(2), 68–82. Russell, J. A. (2011). Graduate teaching-assistant development in college and university instructional physical activity programs. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, & Dance, 82(4), 22– 32. doi:10.1080/07303084.2011.10598610 Sackett, D. L., Rosenburg, W. M., Gray, J. A., Haynes, R. B., & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based-medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal, 312(7023), 71–72. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71 Sallis, J. F., & McKenzie, T. L. (1991). Physical education’s role in public health. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 62, 124–137. doi:10.1080/02701367.1991.10608701 Sallis, J. F., McKenzie, T. L., Beets, M. W., Beighle, A., Erwin, H., & Lee, S. (2012). Physical education’s role in public health: Steps forward and backward over 20 years and HOPE for the future. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 83(2), 125–135. Sallis, J. F., & Owen, N. (2002). Ecological models of health behavior. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & F. Marcus-Lewis (Eds.), Health behavior and health education (3rd ed., pp. 462–470). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Savage, M. P. (1998). University students’ motivation for participation in a basic instruction program. College Student Journal, 32(1), 58–66. Siedentop, D., Hastie, P. A., & van der Mars, H. (2011). Complete guide to sport education (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Skeat, W.W. (1882). The Book of Husbandry by Master Fitzherbert. London, UK: Trubner & Co. Slava, S., Laurie, D. R., & Corbin, C. B. (1984). Long-term effects of a conceptual physical education program. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 55, 161–168. doi:10.1080/ 02701367.1984.10608393 Society for Health and Physical Educators. (2013). Comprehensive school physical activity programs: Helping students achieve 60 minutes of physical activity each day [Position statement]. Reston, VA: Author. Sparling, P. B. (2003). College physical education: An unrecognized agent of change in combating inactivity-related diseases. Perspectives in Biology & Medicine, 46, 579–587. doi:10.1353/ pbm.2003.0091 Sparling, P. B., & Snow, T. K. (2002). Physical activity patterns in recent college alumni. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 73, 200–205. doi:10.1080/02701367.2002.10609009 Stapleton, D., & Bulger, S. M. (2015). Adherence to appropriate instructional practice guidelines in U.S. colleges’ and universities’ physical activity programs. Journal of Physical Education and Sport Management, 6(7), 47–59. Stokols, D. (1992). Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist, 47(1), 6–22. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.1.6 Stokols, D. (1996). Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10, 282–298. doi:10.4278/0890-117110.4.282 418 D. T. STAPLETON ET AL. Sweeney, M. M. (2011). Initiating and strengthening college and university physical activity programs. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, & Dance, 82(4), 17–21. doi:10.1080/ 07303084.2011.10598609 Teichler, U. (2003). The future of higher education and the future of higher education research, Tertiary Education and Management. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Tertiary Education and Management, 9, 171–185. doi:10.1080/13583883.2003.9967102 Trimble, R. T., & Hensley, L. D. (1984). The general instruction program in physical education at four-year colleges and universities: 1982. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, & Dance, 55 (5), 82–89. doi:10.1080/07303084.1984.10629778 Trimble, R. T., & Hensley, L. D. (1990). Basic instruction programs at four-year colleges and universities. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, & Dance, 61(6), 64–73. doi:10.1080/ 07303084.1990.10604555 U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education Programs. (2011). Creating equal opportunities for children and youth with disabilities to participate in physical education and extracurricular athletics. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1996). Physical activity and health: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hpdata2010/hp2010_final_review.pdf U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2010). Students with disabilities: More information and guidance could improve opportunities in physical education and athletics. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/assets/310/305770.pdf Veloutsou, C., Lewis, J. W., & Paton, R. A. (2004). University selection: Information requirements and importance. The International Journal of Educational Management, 18, 160–171. doi:10.1108/09513540410527158 Wang, J., Castelli, D. M., Liu, W., Bian, W., & Tan, J. (2010). Re-conceptualizing physical education programs from an ecological perspective. Asian Journal of Exercise & Sports Science, 7(1), 43–53. Webster, C. A., Webster, L., Russ, L., Molina, S., Lee, H., & Cribbs, J. (2015). A systematic review of public health-aligned recommendations for preparing physical education teacher candidates. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 86(1), 30–39. doi:10.1080/02701367.2014.980939