Dickinson's 'After Great Pain': Analysis & Interpretation

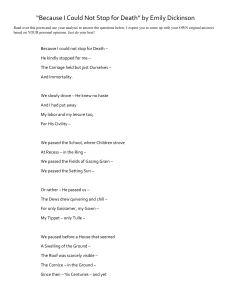

advertisement

‘After Great Pain’ by Dickinson is a poem that reveals the painful and intrinsic suffering of mankind - yet also the power and relief that might be gained from such despair. As Kay Cornelius put it, ‘Dickinson, like much of her writing, was a paradox.’ The poem challenges religious dogma, praises nature’s assuaging qualities, and ultimately leaves readers with an unfinalized sense of awe and appreciation of that relief that ensues from ‘Great Pain.’ Shira Wolosky’s critical opinion that she sees ‘Dickinson as a powerful agnostic voice’ can be supported by the poem. Dickinson herself was skeptical of the utility of organized religion’s rigid structures, particularly the Puritan and Calvinist roots, as a service to truly resolve man’s struggles. This might generally be interpreted as a challenge to how well religion can truly curb our sufferings - demonstrated by the spondee in ‘great pain’ that accentuates the suffering of man. Additionally, by not using the common meter in the first stanza, as was typical with her hymn-like poems, and disrupting the natural iambic pentameter of the poem, this may be a subliminal hint at how the vicissitudes of life are forever part of life and too significant for religion to curtail. The synecdoche of the ‘stiff Heart’ characterizes a man as an emotionally devoid soul, one that has been sucked of joy and left almost traumatized in a cataleptic state due to his ‘great pain’ - despite religion’s pervasive attempts to soothe mankind’s afflicted souls. An explicit allusion to the crucifixion of Jesus is used when she questions ‘was it He, that bore’ that excruciating pain those ‘Centuries before?, with the capitalization clearly identifying the man of the subject being Jesus. This questioning of the scripture and reality of Jesus’ crucifixion, in and of itself at the time, might easily be seen as blasphemy - supporting the view that Dickinson was a ‘powerful agnostic voice’ - during the periods of the Great Revivals that proliferated the 19th Century in America and her town. Jesus’ pain that was as real as ‘Yesterday’ might be alluding to these common declarations of ‘seeing’ and ‘talking to God’ in her hometown - yet the ‘stiff Heart [that] questions’ this undermines the utility these proclamations to actually do anything to soothe man’s ‘great pain’ in the world. The question of ‘was it He’, Jesus’, within the ‘great pain’ context of the poem, brings in to mind the possibility that perhaps it was not just ‘He’ that experienced immense torture ‘Centuries before’, but perhaps the common everyday man might be facing similar challenges in day to day life, ‘Yesterday’ too. The repetitive temporal dislocation that Dickinson uses here calls attention to whether or not these beliefs that persist might simply be ephemeral. With the increasing scientific and philosophical schools of thought that questioned religion, and Dickinson’s own skepticism as a potential ‘agnostic voice’, this may be interpreted as a doubting of religion’s attempts at aiding man in life’s hardships - hence making a ‘powerful agnostic voice.’ Yet Dickinson did not appear to be atheist, but instead embodied a transcendentalist perspective as she ‘always held nature in reverence’ as she saw it as ‘almost religious, (Benjamin Barber), using it and immersing herself in it to empower herself in her times of despair. Kay Cornelius stated how Dickinson ‘often used the metaphor of journey to describe her feelings,’ and that is illustrated in the poem by the synecdoche of ‘The Feet,’ which symbolize man’s naked and vulnerable, treacherous, unpredictable, ‘great-pain-filled’ path in life. But man does not have to bear the burden of life alone, as he can use nature’s wood to craft a ‘Wooden way,’ for him to walk on. The definite article and capitalization of ‘The Feet’ highlight how it is certainly mankind who walks this path; but the indefinite article of ‘A Wooden way’ suggests that nature has many different facets and uses and that using it to aid our hardships is just one of the many beautiful services of nature. Though the imagery of us ‘spinning our wheels’ in our own lives is portrayed by how our ‘Feet…go round’ in ‘air, or Ought’ - giving us a sense of hopelessness - we have ‘Regardless grown’ from it all, with nature’s aid. This volta indicated by the dash after ‘Ought’ highlights how with nature and the ‘Wooden way’ we have crafted with it, we have emerged as something stronger ‘after great pain.’ By shifting from a nihilistic hopelessness despondency to a life with potential and ability to overcome life’s challenges with nature, Dickinson vivifies the inextricable link man has with nature as a means to go about living.