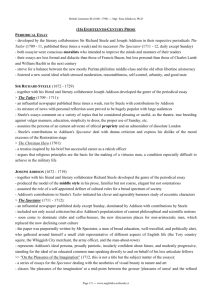

УСРС ЛЕКЦИЯ 1 1. Joseph Addison’s life and journalistic activities. Joseph Addison’s Cato, a Tragedy Joseph Addison (1 May 1672 – 17 June 1719) was an English essayist, poet, playwright and politician. He was the eldest son of The Reverend Lancelot Addison. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his longstanding friend Richard Steele, with whom he founded The Spectator magazine. His simple prose style marked the end of the mannerisms and conventional classical images of the 17th century. Addison was born in Milston, Wiltshire, but soon after his birth his father, Lancelot Addison, was appointed Dean of Lichfield and the family moved into the cathedral close. Joseph was educated at Charterhouse School, London, where he first met Richard Steele, and at The Queen's College, Oxford. Political career[edit] Addison returned to England at the end of 1703. His next literary venture was an account of his travels in Italy, Remarks on several parts of Italy, &c., in the years 1701, 1702, 1703, published in 1705 by Jacob Tonson.[4] In 1705, with the Whigs in power, Addison was made Under-Secretary of State and accompanied Lord Halifax on a diplomatic mission to Hanover, Germany. Under the direction of Wharton, he was an MP in the Irish House of Commons for Cavan Borough from 1709 until 1713. In 1710, he represented Malmesbury, in his home county of Wiltshire, holding the seat until his death in 1719. He met Jonathan Swift in Ireland and remained there for a year. Later, he helped form the Kitcat Club and renewed his friendship with Richard Steele. In 1709, Steele began to publish the Tatler, and Addison became a regular contributor. In 1711 they began The Spectator; its first issue appeared on 1 March 1711. This paper, which was originally a daily, was published until 20 December 1714, interrupted for a year by the publication of The Guardian in 1713. His last publication was The Freeholder, a political paper, in 1715–16. Plays[edit] He wrote the libretto for Thomas Clayton's opera Rosamond, which had a disastrous premiere in London in 1707.[6] In 1713 Addison's tragedy Cato was produced, and was received with acclamation by both Whigs and Tories. He followed this effort with a comedic play, The Drummer (1716). Cato Main article: Cato, a Tragedy In 1712, Addison wrote his most famous work, Cato, a Tragedy. Based on the last days of Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis, it deals with conflicts such as individual liberty versus government tyranny, Republicanism versus Monarchism, logic versus emotion, and Cato's personal struggle to retain his beliefs in the face of death. It has a prologue written by Alexander Pope and an epilogue by Samuel Garth.[7] The play was a success throughout the British Empire. General George Washington sponsored a performance of Cato for the Continental Army during the difficult winter of 1777–78 at Valley Forge. According to John J. Miller, "no single work of literature may have been more important than Cato" for the leaders of the American revolution.[8] Scholars have identified the inspiration for several famous quotations from the American Revolution in Cato. These include: Patrick Henry's famous ultimatum: "Give me liberty or give me death!" Nathan Hale's valediction: "I regret that I have but one life to give for my country." Washington's praise for Benedict Arnold in a letter: "It is not in the power of any man to command success; but you have done more – you have deserved it." Though the play has fallen from popularity and is now rarely performed, it was popular and often cited in the eighteenth century, with Cato being an example of republican virtue and liberty. John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon were inspired by the play to write an epistolary exchange entitled Cato's Letters (1720–1723), concerning individual rights, using the name "Cato".[citation needed] The action of the play involves the forces of Cato at Utica, awaiting the attack of Caesar immediately following his victory at Thapsus (46 BC). The noble sons of Cato, Portius and Marcus, are both in love with Lucia, the daughter of Lucius, an ally of Cato. Juba, prince of Numidia, one of Cato's warriors, loves Cato's daughter Marcia. Meanwhile, Sempronius, a senator, and Syphax, a general of the Numidians, are conspiring secretly against Cato, hoping to prevent the Numidian army from supporting him. In the final act, Cato commits suicide, leaving his followers to make their peace with the approaching army of Caesar – an easier task after Cato's death, since he was Caesar's most implacable enemy. 2. Richard Steele’s life and journalistic activities. Richard Steele’s sentimental comedy The Conscious Lovers Sir Richard Steele (bap. 12 March 1672 – 1 September 1729) was an Irish writer, playwright, and politician, remembered as co-founder, with his friend Joseph Addison, of the magazine The Spectator. Steele was born in Dublin, Ireland, in March 1672 to Richard Steele, a wealthy attorney, and Elinor Symes (née Sheyles); his sister Katherine was born the previous year. He was the grandson of Sir William Steele, Lord Chancellor of Ireland and his first wife Elizabeth Godfrey. His father lived at Mountown House, Monkstown, County Dublin. His father died when he was four, and his mother a year later. Steele was largely raised by his uncle and aunt, Henry Gascoigne (secretary to James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde), and Lady Katherine Mildmay.[1] A member of the Protestant gentry, he was educated at Charterhouse School, where he first met Addison. After starting at Christ Church, Oxford, he went on to Merton College, Oxford, then joined the Life Guards of the Household Cavalry in order to support King William's wars against France. He was commissioned in 1697, and rose to the rank of captain within two years.[2] Steele left the army in 1705, perhaps due to the death of the 34th Foot's commanding officer, Lord Lucas, which limited his opportunities of promotion. In 1706 Steele was appointed to a position in the household of Prince George of Denmark, consort of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. He also gained the favour of Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford. Steele became a Whig Member of Parliament in 1713, for Stockbridge.[3] He was soon expelled for issuing a pamphlet in favor of the Hanoverian succession. When George I of Great Britain came to the throne in the following year, Steele was knighted and given responsibility for the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London. He returned to parliament in 1715, for Boroughbridge.[4] While at Drury Lane, Steele wrote and directed the sentimental comedy The Conscious Lovers, which was an immediate hit. However, he fell out with Addison and with the administration over the Peerage Bill (1719), and in 1724 he retired to his second wife's homeland of Wales, where he spent the remainder of his life.[5] Steele was a member of the Kit-Kat Club. Both Steele and Addison became closely associated with Child's Coffee-house in St Paul's Churchyard. Steele's first published work, The Christian Hero (1701), attempted to point out the differences between perceived and actual masculinity. Written while Steele served in the army, it expressed his idea of a pamphlet of moral instruction. The Christian Hero was ultimately ridiculed for what some thought was hypocrisy because Steele did not necessarily follow his own preaching. He was criticized[by whom?] for publishing a booklet about morals when he himself enjoyed drinking, occasional dueling, and debauchery around town. Steele wrote a comedy that same year titled The Funeral. This play met with wide success and was performed at Drury Lane, bringing him to the attention of the King and the Whig party. Next, Steele wrote The Lying Lover, one of the first sentimental comedies, but a failure on stage. In 1705, Steele wrote The Tender Husband with contributions from Addison's, and later that year wrote the prologue to The Mistake, by John Vanbrugh, also an important member of the Whig Kit-Kat Club with Addison and Steele. He wrote a preface to Addison's 1716 comedy play The Drummer. The Tatler, Steele's first journal, first came out on 12 April 1709, and appeared three times a week: on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. Steele wrote this periodical under the pseudonym Isaac Bickerstaff and gave Bickerstaff an entire, fully developed personality. Steele described his motive in writing The Tatler as "to expose the false arts of life, to pull off the disguises of cunning, vanity, and affectation, and to recommend a general simplicity in our dress, our discourse, and our behaviour".[7] Steele founded the magazine, and although he and Addison collaborated, Steele wrote the majority of the essays; Steele wrote roughly 188 of the 271 total and Addison 42, with 36 representing the pair's collaborative works. While Addison contributed to The Tatler, it is widely regarded as Steele's work.[8] The Tatler was closed down to avoid the complications of running a Whig publication that had come under Tory attack.[9] Addison and Steele then founded The Spectator in 1711 and also the Guardian in 1713. 3. Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman: plot, style, techniques Laurence Sterne (24 November 1713 – 18 March 1768), an Anglo-Irish novelist and Anglican cleric, wrote the novels The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman and A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, published sermons and memoirs, and indulged in local politics. He grew up in a military family travelling mainly in Ireland but briefly in England. An uncle paid for Sterne to attend Hipperholme Grammar School in the West Riding of Yorkshire, as Sterne's father was ordered to Jamaica, where he died of malaria some years later. He attended Jesus College, Cambridge on a sizarship, gaining bachelor's and master's degrees. At the age of 46, Sterne dedicated himself to writing for the rest of his life. It was while living in the countryside, having failed in his attempts to supplement his income as a farmer and struggling with tuberculosis, that Sterne began work on his best-known novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, the first volumes of which were published in 1759. Sterne was at work on his celebrated comic novel during the year that his mother died, his wife was seriously ill, and his daughter was also taken ill with a fever.[26] He wrote as fast as he possibly could, composing the first 18 chapters between January and March 1759.[27] Due to his poor financial position, Sterne was forced to borrow money for the printing of his novel, suggesting that Sterne was confident in the prospective commercial success of his work and that the local critical reception of the novel was favourable enough to justify the loan.[28] The publication of Tristram Shandy made Sterne famous in London and on the continent. He was delighted by the attention, famously saying "I wrote not [to] be fed but to be famous."[29] He spent part of each year in London, being fêted as new volumes appeared. Even after the publication of volumes three and four of Tristram Shandy, his love of attention (especially as related to financial success) remained undiminished. In one letter, he wrote "One half of the town abuse my book as bitterly, as the other half cry it up to the skies — the best is, they abuse it and buy it, and at such a rate, that we are going on with a second edition, as fast as possible."[30] Indeed, Baron Fauconberg rewarded Sterne by appointing him as the perpetual curate of Coxwold, North Yorkshire in March 1760.[31] In 1766, at the height of the debate about slavery, the composer and former slave Ignatius Sancho wrote to Sterne[32] encouraging him to use his pen to lobby for the abolition of the slave trade.[33] In July 1766 Sterne received Sancho's letter shortly after he had finished writing a conversation between his fictional characters Corporal Trim and his brother Tom in Tristram Shandy, wherein Tom described the oppression of a black servant in a sausage shop in Lisbon which he had visited.[34] Sterne's widely publicised response to Sancho's letter became an integral part of 18th-century abolitionist literature.[34] Sterne's novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman sold widely in England and throughout Europe.[56] Translations of the work began to appear in all the major European languages almost upon its publication, and Sterne influenced European writers as diverse as Denis Diderot[57] and the German Romanticists.[58] His work had also noticeable influence over Brazilian author Machado de Assis, who made use of the digressive technique in the novel The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas.[59] English writer and literary critic Samuel Johnson's verdict in 1776 was that "Nothing odd will do long. Tristram Shandy did not last."[60] This is strikingly different from the views of European critics of the day, who praised Sterne and Tristram Shandy as innovative and superior. Voltaire called it "clearly superior to Rabelais", and later Goethe praised Sterne as "the most beautiful spirit that ever lived".[52] Swedish translator Johan Rundahl described Sterne as an arch-sentimentalist.[61] The title page to volume one includes a short Greek epigraph, which in English reads: "Not things, but opinions about things, trouble men."[62] Before the novel properly begins, Sterne also offers a dedication to Lord William Pitt.[63] He urges Pitt to retreat with the book from the cares of statecraft.[64] The novel itself starts with the narration, by Tristram, of his own conception. It proceeds mostly by what Sterne calls "progressive digressions" so that we do not reach Tristram's birth before the third volume.[65][66] The novel is rich in characters and humour, and the influences of Rabelais and Miguel de Cervantes are present throughout. The novel ends after 9 volumes, published over a decade, but without anything that might be considered a traditional conclusion. Sterne inserts sermons, essays and legal documents into the pages of his novel; and he explores the limits of typography and print design by including marbled pages and an entirely black page within the narrative.[52] Many of the innovations that Sterne introduced, adaptations in form that were an exploration of what constitutes the novel, were highly influential to Modernist writers like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, and more contemporary writers such as Thomas Pynchon and David Foster Wallace.[67] Italo Calvino referred to Tristram Shandy as the "undoubted progenitor of all avant-garde novels of our century".[67] The Russian Formalist writer Viktor Shklovsky regarded Tristram Shandy as the archetypal, quintessential novel, "the most typical novel of world literature."[68] УСРС ЛЕКЦИЯ 2 1. Samuel Richardson’s Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded: plot, genre and criticism. Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded is an epistolary novel first published in 1740 by English writer Samuel Richardson. Considered one of the first true English novels, it serves as Richardson's version of conduct literature about marriage. Pamela tells the story of a fifteen-year-old maidservant named Pamela Andrews, whose employer, Mr. B, a wealthy landowner, makes unwanted and inappropriate advances towards her after the death of his mother. Pamela strives to reconcile her strong religious training with her desire for the approval of her employer in a series of letters and, later in the novel, journal entries all addressed to her impoverished parents. After various unsuccessful attempts at seduction, a series of sexual assaults, and an extended period of kidnapping, the rakish Mr. B eventually reforms and makes Pamela a sincere proposal of marriage. In the novel's second part Pamela marries Mr. B and tries to acclimatise to her new position in upper-class society. The full title, Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded, makes plain Richardson's moral purpose. A best-seller of its time, Pamela was widely read but was also criticised for its perceived licentiousness and disregard for class barriers. Furthermore, Pamela was an early commentary on domestic violence and brought into question the dynamic line between male aggression and a contemporary view of love. Moreover, Pamela, despite the controversies, was able to shed light on social issues that transcended the novel for the time such as gender roles, early false-imprisonment, and class barriers present in the eighteenth century. The action of the novel is told through letters and journal entries from Pamela to her parents. Richardson highlights a theme of naivety, illustrated through the eyes of Pamela. Richardson paints Pamela herself as innocent and meek to further contribute to the theme of her being short-sighted to emphasize the ideas of childhood innocence and naivety. Richardson began writing Pamela after he was approached by two book sellers who requested that he make them a book of letter templates. Richardson accepted the request, but only if the letters had a moral purpose. As Richardson was writing the series of letters turned into a story. [4] Writing in a new form, the novel, Richardson attempted to both instruct and entertain. Richardson wrote Pamela as a conduct book, a sort of manual which codified social and domestic behavior of men, women, and servants, as well as a narrative in order to provide a more morally concerned literature option for young audiences. Ironically, some readers focused more upon the bawdy details of Richardson's novel, resulting in some negative reactions and even a slew of literature satirizing Pamela, and so he published a clarification in the form of A Collection of the Moral and Instructive Sentiments, Maxims, Cautions, and Reflexions, Contained in the Histories of Pamela, Clarissa, and Sir Charles Grandison in 1755. [5] Many novels, from the mid-18th century and well into the 19th, followed Richardson's lead and claimed legitimacy through the ability to teach as well as amuse. In the novel, Pamela writes two kinds of letters. At the beginning, while she decides how long to stay on at Mr. B's after his mother's death, she tells her parents about her various moral dilemmas and asks for their advice. After Mr. B. abducts her and imprisons her in his country house, she continues to write to her parents, but since she does not know if they will ever receive her letters, the writings are also considered a diary. Eventually, Mr. B finds out about Pamela's letters to her parents and encroached upon her privacy by refusing to let her send them. The plot of Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded is bound up in the back-and-forth between Pamela and Mr. B as the former eludes B's attempt and the latter, growing frustrated, continues in his attempts. According to Barbara Belyea, Pamela's “duty to resist him without compromise has become a duty to obey him without question” (411).[8] In other words, readers of Pamela experience the trajectory of the plot, and the romance between the hero and heroine, as a back-and-forth, pendulum-like swing. Belyea claims this oscillation persists through readers' interpretations as Pamela sustains the formative action of the plot through the letters she writes to her parents detailing her ordeal: "Within the fictional situation, the parents' attitude to their child's letters is the closest to that of Richardson's reader. The parents' sympathy for the heroine and anxiety for a happy end anticipate the reader's attitude to the narrative" (413).[8] Pamela's parents are the audience for her letters and their responses (as recipients of the letters) mimic what Belyea argues are readers’ responses to Richardson's novel. Arguably, Richardson's Pamela invokes an audience within an audience and "[c]areful attention to comments and letters by other characters enables the reader to perceive that Pamela's passionate defence of her chastity is considered initially as exaggerated, fantastic-in a word, romantic" (412).[8] Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded demonstrates morality and realism as bound up in individuals’ identities and social class because of its form as an epistolary novel. 2. Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa, or, the History of a Young Lady: plot, genre and criticism. Clarissa; or, The History of a Young Lady: Comprehending the Most Important Concerns of Private Life. And Particularly Shewing, the Distresses that May Attend the Misconduct Both of Parents and Children, In Relation to Marriage is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson, published in 1748. It tells the tragic story of a young woman, Clarissa Harlowe, whose quest for virtue is continually thwarted by her family. The Harlowes are a recently wealthy family whose preoccupation with increasing their standing in society leads to obsessive control of their daughter, Clarissa. It is considered one of the longest novels in the English language (based on estimated word count). It is generally regarded as Richardson's masterpiece. Robert Lovelace, a wealthy "libertine" and heir to a substantial estate, begins to court Arabella, Clarissa's older sister. However, she rejects him because she felt slighted by his more ardent interest in her parents' approval than in her. Lovelace quickly moves on from Arabella to Clarissa, much to the displeasure of Arabella and their brother James. Clarissa insists that she dislikes Lovelace, but Arabella grows jealous of Lovelace's interest in the younger girl. James, also, dislikes Lovelace greatly because of a duel the two had once fought. These feelings combine with resentment that their grandfather had left Clarissa a piece of land and lead the siblings to be aggressive to Clarissa. The entire Harlowe family is in favour of her marrying Roger Solmes, however Clarissa finds Solmes to be unpleasant company and does not wish to marry him, either. This makes her family suspicious of her supposed dislike of Lovelace and they begin to disbelieve her. The Harlowes begin restricting Clarissa's contact with the outside world by forbidding her to see Lovelace. Eventually they forbid her to either leave her room or send letters to her friend, Anna Howe, until Clarissa apologises and agrees to marry Solmes. Trapped and desperate to regain her freedom, Clarissa continues to communicate with Anna secretly and begins a correspondence with Lovelace while trying to convince her parents not to force her to marry Solmes. Neither Clarissa nor her parents will concede. They see her protests as stubborn disobedience and communication between parents and daughter breaks down. Lovelace convinces Clarissa to elope with him to avoid the conflict with her parents. Joseph Leman, a servant of the Harlowe family, shouts and makes noise so it may seem like the family has awoken and discovered that Clarissa and Lovelace are about to run away.[clarification needed] Frightened of the possible aftermath, Clarissa leaves with Lovelace but becomes his prisoner for many months. Her family now will not listen to or forgive Clarissa because of this perceived betrayal, despite her continued attempts to reconcile with them. She is kept at many lodgings, including unknowingly a brothel, where the women are disguised as high-class ladies by Lovelace so as to deceive Clarissa. Despite all of this, she continues to refuse Lovelace, longing to live by herself in peace. Eventually, surrounded by strangers and her cousin, Col. Morden, Clarissa dies in the full consciousness of her virtue and trusting in a better life after death. Belford manages Clarissa's will and ensures that all her articles and money go into the hands of the individuals she desires should receive them. Lovelace departs for Europe and continues to correspond with Belford. Lovelace learns that Col. Morden has suggested he might seek Lovelace and demand satisfaction on behalf of his cousin. He responds that he is not able to accept threats against himself and arranges an encounter with Col. Morden. They meet in Munich and arrange a duel. Morden is slightly injured in the duel, but Lovelace dies of his injuries the following day. Before dying he says "let this expiate!" Clarissa's relatives finally realise they have been wrong but it comes too late. They discover Clarissa has already died. The story ends with an account of the fate of the other characters. Clarissa is generally regarded by critics to be among the masterpieces of eighteenth-century European literature. Influential critic Harold Bloom cites it as one of his favourite novels that he "tend[s] to re-read every year or so".[4] The novel was well-received as it was being released. However, many readers pressured Richardson for a happy ending with a wedding between Clarissa and Lovelace.[5] At the novel's end, many readers were upset, and some individuals even wrote alternative endings for the story with a happier conclusion. Some of the most well-known ones included happier alternative endings written by two sisters Lady Bradshaigh and Lady Echlin.[6] Richardson felt that the story's morals and messages of the story failed to reach his audience properly. As such, in later editions of the novel, he attempted to make Clarissa's character appear purer while also Lovelace's character became more sinister in hopes of making his audience better understand his intentions in writing the novel.[5] The pioneering American nurse Clara Barton's full name was Clarissa Harlowe Barton, after the heroine of Richardson's novel. 3. Samuel Richardson’s The History of Sir Charles Grandison: plot, themes, structure The History of Sir Charles Grandison, commonly called Sir Charles Grandison, is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson first published in February 1753. The book was a response to Henry Fielding's The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, which parodied the morals presented in Richardson's previous novels.[1] The novel follows the story of Harriet Byron who is pursued by Sir Hargrave Pollexfen. After she rejects Pollexfen, he kidnaps her, and she is only freed when Sir Charles Grandison comes to her rescue. After his appearance, the novel focuses on his history and life, and he becomes its central figure. As with his previous novels, Richardson prefaced the novel by claiming to be merely the editor, saying, "How such remarkable collections of private letters fell into the editor's hand he hopes the reader will not think it very necessary to enquire".[2]: 146 However, Richardson did not keep his authorship secret and, on the prompting of his friends like Samuel Johnson, dropped this framing device from the second edition.[2]: 146 Pollexfen, unwilling to be without Byron, decides to kidnap her while she attended a masquerade ball at the Haymarket. She is then imprisoned at Lisson Grove with the support of a widow and two daughters. While he keeps her prisoner, Pollexfen makes it clear to her that she shall be his wife, and that anyone who challenges that will die by his hand. Byron attempts to escape from the house, but this fails. To prevent her from trying to escape again, Pollexfen transports Byron to his home at Windsor. However, he is stopped at Hounslow Heath, where Charles Grandison hears Byron's pleas for help and immediately attacks Pollexfen. After this rescue, Grandison takes Byron to Colnebrook, the home of Grandison's brother-in-law, the "Earl of L.". n a "Concluding Note" to Grandison, Richardson writes: "It has been said, in behalf of many modern fictitious pieces, in which authors have given success (and happiness, as it is called) to their heroes of vicious if not profligate characters, that they have exhibited Human Nature as it is. Its corruption may, indeed, be exhibited in the faulty character; but need pictures of this be held out in books? Is not vice crowned with success, triumphant, and rewarded, and perhaps set off with wit and spirit, a dangerous representation?"[4]: 149 In particular, Richardson is referring to novels of Fielding, his literary rival.[4]: 149 This note was published with the final volume of Grandison in March 1754, a few months before Fielding left for Lisbon.[4]: 149 Before Fielding died in Lisbon, he included a response to Richardson in his preface to Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon.[4]: 149 20th-century literary critic Carol Flynn characterises Sir Charles Grandison as a "man of feeling who truly cannot be said to feel".[5]: 47 Flynn claims that Grandison is filled with sexual passions that never come to light, and he represents a perfect moral character in regards to respecting others. Unlike Richardson's previous novel Clarissa, there is an emphasis on society and how moral characteristics are viewed by the public. As such, Grandison stresses characters acting in the socially accepted ways instead of following their emotional impulses. The psychological realism of Richardson's earlier work gives way to the expression of exemplars. In essence, Grandison promises "spiritual health and happiness to all who follow the good man's exemplary pattern".[5]: 47–9 This can be taken as a sort of "political model of the wise ruler", especially with Charles's somewhat pacifist methods of achieving his goals.[7]: 111 In terms of religious responsibility, Grandison is unwilling to change his faith, and Clementina initially refuses to marry him over his religion. Grandison attempts to convince her to reconsider by claiming that "her faith would not be at risk".[8]: 70 Although potentially controversial to the 18th century British public, Grandison and Clementina compromise by agreeing that their sons would be raised as Protestants and their daughters raised as Catholics.[8]: 71–2 In addition to the religious aspects, the work gives "the portrait of how a good marriage should be created and sustained".[9]: 128 To complement the role of marriage, Grandison opposes "sexual deviance" in the 18th century.[9]: 131 The epistolary form unites The History of Sir Charles Grandison with Richardson's Pamela and Clarissa, but Richardson uses the form in a different way for his final work. In Clarissa, the letters emphasise the plot's drama, especially when Lovelace alters Clarissa's letters. However, the dramatic mood is replaced in Grandison with a celebration of Grandison's moral character. In addition to this lack of dramatic emphasis, the letters of Grandison do not serve to develop character, as the moral core of each character is already complete at the outset.[5]: 236, 58 In Richardson's previous novels, the letters operated as a way to express internal feelings and describe the private lives of characters; however, the letters of Grandison serve a public function.[5]: 258 The letters are not kept to individuals, but forwarded to others to inform a larger community of the novel's action. In return, letters share the recipients' responses to the events detailed within the letters.[6] This sharing of personal feelings transforms the individual responders into a chorus that praises the actions of Grandison, Harriet, and Clementina. Furthermore, this chorus of characters emphasises the importance of the written word over the merely subjective, even saying that "Love declared on paper means far more than love declared orally".[5]: 258 УСРС ЛЕКЦИЯ 3 1. James Macpherson’s life and his Poems of Ossian: significance, authenticity debate, reception ames Macpherson (Gaelic: Seumas MacMhuirich or Seumas Mac a' Phearsain; 27 October 1736 – 17 February 1796) was a Scottish writer, poet, literary collector and politician, known as the "translator" of the Ossian cycle of epic poems. Macpherson was born at Ruthven in the parish of Kingussie in Badenoch, Inverness-shire. This was a Scottish Gaelic-speaking area but near the Barracks of the British Army, established in 1719 to enforce Whig rule from London after the Jacobite uprising of 1715. Macpherson's uncle, Ewen Macpherson joined the Jacobite army in the 1745 march south, when Macpherson was nine years old and after the Battle of Culloden, had had to remain in hiding for nine years.[1] In the 1752-3 session, Macpherson was sent to King's College, Aberdeen, moving two years later to Marischal College (the two institutions later became the University of Aberdeen), reading Caesar's Commentaries on the relationships between the 'primitive' Germanic tribes and the 'enlightened' Roman imperial army;[1] it is also believed that he attended classes at the University of Edinburgh as a divinity student in 1755–56. During his years as a student, he ostensibly wrote over 4,000 lines of verse, some of which was later published, notably The Highlander (1758), a six-canto epic poem,[2] which he attempted to suppress sometime after its publication. On leaving college, he returned to Ruthven to teach in the school there, and then became a private tutor.[1] At Moffat he met John Home, the author of Douglas, for whom he recited some Gaelic verses from memory. He also showed him manuscripts of Gaelic poetry, supposed to have been picked up in the Scottish Highlands and the Western Isles; one was called The Death of Oscar.[1] Encouraged by Home and others, Macpherson produced 15 pieces, all laments for fallen warriors, translated from the Scottish Gaelic, despite his limitations in that tongue, which he was induced to publish at Edinburgh in 1760, including the Death of Oscar, in a pamphlet: Fragments of Ancient Poetry collected in the Highlands of Scotland. Extracts were then published in The Scots Magazine and The Gentleman's Magazine which were popular and the notion of these fragments as glimpses of an unrecorded Gaelic epic began.[1] Hugh Blair, who was a firm believer in the authenticity of the poems, raised a subscription to allow Macpherson to pursue his Gaelic researches. In the autumn,1760, Macpherson set out to visit western Inverness-shire, the islands of Skye, North Uist, South Uist and Benbecula. Allegedly, Macpherson obtained manuscripts which he translated with the assistance of a Captain Morrison and the Rev. Gallie. Later he made an expedition to the Isle of Mull, where he claimed to obtain other manuscripts. In 1761, Macpherson announced the discovery of an epic on the subject of Fingal (related to the Irish mythological character Fionn mac Cumhaill/Finn McCool) written by Ossian (based on Fionn's son Oisín), and in December he published Fingal, an Ancient Epic Poem in Six Books, together with Several Other Poems composed by Ossian, the Son of Fingal, translated from the Gaelic Language, written in the musical measured prose of which he had made use in his earlier volume. Temora followed in 1763, and a collected edition, The Works of Ossian, in 1765. The name Fingal or Fionnghall means "white stranger",[5] and it is suggested that the name was rendered as Fingal through a derivation of the name which in old Gaelic would appear as Finn.[6] The authenticity of these so-called translations from the works of a 3rd-century bard was immediately challenged by Irish historians, especially Charles O'Conor, who noted technical errors in chronology and in the forming of Gaelic names, and commented on the implausibility of many of Macpherson's claims, none of which Macpherson was able to substantiate. More forceful denunciations were later made by Samuel Johnson, who asserted (in A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland, 1775) that Macpherson had found fragments of poems and stories, and then woven them into a romance of his own composition. Further challenges and defences were made well into the nineteenth century, but the issue was moot by then. Macpherson's manuscript Gaelic "originals" were published posthumously in 1807;[7] Ludwig Christian Stern was sure they were in fact back-translations from his English version.[8] 2. Thomas Percy’s life and his Reliques of Ancient English Poetry: sources, content, reception Thomas Percy (13 April 1729 – 30 September 1811) was Bishop of Dromore, County Down, Ireland. Before being made bishop, he was chaplain to George III of the United Kingdom. Percy's greatest contribution is considered to be his Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765), the first of the great ballad collections, which was the one work most responsible for the ballad revival in English poetry that was a significant part of the Romantic movement. He was born as Thomas Percy in Bridgnorth, the son of Arthur Lowe Percy a grocer and farmer at Shifnal who sent Thomas to Christ Church, Oxford in 1746 following an education firstly at Bridgnorth Grammar School followed by nearby Adams' Grammar School in Newport. He graduated in 1750 and proceeded M.A. in 1753. In the latter year he was appointed to the vicarage of Easton Maudit, Northamptonshire, and three years later was instituted to the rectory of Wilby in the same county, benefices which he retained until 1782. In 1759 he married Anne, daughter of Barton Gutterridge. His wife died before him in 1806; the bishop, blind but otherwise in sound health, lived another five years. Both were buried in the transept which Percy had added to Dromore Cathedral. The basis of the work was the manuscript which became known as the Percy Folio. Percy found the folio in the house of his friend Humphrey Pitt of Shifnal, a small market town of Shropshire. It was on the floor, and Pitt's maid had been using the leaves to light fires. Once rescued, Percy would use just forty-five of the ballads in the folio for his book, despite claiming the bulk of the collection came from this folio. Other sources were the Pepys Library of broadside ballads collected by Samuel Pepys and Collection of Old Ballads published in 1723, possibly by Ambrose Philips. Bishop Percy was encouraged to publish the work by his friends Samuel Johnson and the poet William Shenstone, who also found and contributed ballads. Percy did not treat the folio nor the texts in it with the scrupulous care expected of a modern editor of manuscripts. He wrote his own notes directly on the folio pages, emended the rhymes and even pulled pages out of the document to give to the printer without making copies.[1] He was criticised for these actions even at the time, most notably by Joseph Ritson, a fellow antiquary. The folio he worked from seems to have been written by a single copyist and errors such as pan and wale for wan and pale needed correcting. The Reliques contained one hundred and eighty ballads in three volumes with three sections in each. It contains such important ballads as "The Ballad of Chevy Chase", "The Battle of Otterburn", "Lillibullero", "The Dragon of Wantley", "The Nut-Brown Maid" and "Sir Patrick Spens" along with ballads mentioned by or possibly inspiring Shakespeare, several ballads about Robin Hood and one of the Wandering Jew.[2] The claim that the book contained samples of ancient poetry was only partially correct. The last part of each volume was given over to more contemporary works—often less than a hundred years old—included to stress the continuing tradition of the balladeer. The collection draws on the Folio and on other manuscript and printed sources, but in at least three cases anonymous informants, "ladies" in each case, contributed oral poetry known to them. He made substantial amendments to the Folio text in collaboration with his friend the poet William Shenstone. The dedication to the duchess meant that Thomas Percy arranged the work to give prominence to the border ballads which were composed in and about the Scottish and English borders, specifically Northumberland, home county of the Percies. Percy also omitted some of the racier ballads from the Folio for fear of offending his noble patron: these were first published by F. J. Furnivall in 1868.[3] Ballad collections had appeared before but Percy's Reliques seemed to capture the public imagination like no other. Not only would it inspire poets such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth to compose their own ballads in imitation, it also made the collecting and study of ballads a popular pastime. Sir Walter Scott was another writer inspired by reading the Reliques in his youth, and he published some of the ballads he collected in Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. The more rigorous scholarship of folklorists would eventually supersede Percy's work, most notably in Francis James Child's Child Ballads, but Percy gave impetus to the whole subject. The book is also credited, in part, with changing the prevailing literary movement of the 18th century, NeoClassicism, into Romanticism. The classicist Augustans took as their model the epic hexameters of Virgil's Aeneid and the blank verse of John Milton's three epics. The Reliques highlighted the traditions and folklore of England seen as simpler and less artificial. It would inspire folklore collections and movements in other parts of Europe and beyond, such as the Brothers Grimm, and such movements would act as the foundation of romantic nationalism. The Percy Society was founded in 1840 to continue the work of publishing rare ballads, poems and early texts. 3. Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan’s School for Scandal: plot, themes and ideas The School for Scandal is a comedy of manners written by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. It was first performed in London at Drury Lane Theatre on 8 May 1777. In a part of English high society where gossip runs rampant, a tangle of love has formed. Lady Sneerwell is in love with a young, rebellious man named Charles Surface. However, Charles is in love with Maria, as is his brother Joseph. Maria is in love with Charles, but Lady Sneerwell and Joseph plot to ruin this relationship through rumors of unfaithfulness on Charles' part. At the same time, an older man named Sir Peter Teazle has taken a young wife from the country, now called Lady Teazle; after only a few months of marriage they now bicker constantly about money, driving Lady Teazle to contemplate an affair with Joseph Surface. The plot thickens when Sir Oliver Surface, the rich uncle of Joseph and Charles, returns to town from abroad. He schemes to test the rumors he has heard of Joseph being the well-bred and deserving brother and Charles having fallen into ruin; to do so, he goes to each of them in disguise. He disguises himself as a money lender named Mr. Premium to investigate Charles's spending habits, and is infuriated when he sees Charles living lavishly while driving the family far into debt. Charles proposes to sell him all he has left, the collection of family portraits, angering his uncle even more; however he forgives him when Charles refuses to sell the painting of his uncle. The tangle of love and rumors becomes clear when, while Lady Teazle is visiting Joseph Surface, her husband comes to call. Lady Teazle hides behind a screen and listens to their conversation. Then, Charles Surface comes to call on his brother as well; Sir Teazle, hoping to see whether Charles is having an affair with his wife as has been rumored, also tries to hide behind the screen. He sees what he thinks is simply a young woman Joseph has been trying to hide. Sir Teazle hides in the closet instead, but when Charles starts to talk about Joseph's relationship with Lady Teazle, Joseph reveals that Sir Teazle is hiding in the closet, and Charles pulls him out. When Joseph goes out of the room momentarily, Sir Teazle tells Charles about the young woman he thinks is hiding behind the screen, and they pull it down to reveal his wife. Sir Oliver visits Joseph dressed as one of their poor relations looking for money. Sir Oliver is disappointed to find that Joseph is only kind on the surface, but will not do anything material to help his relative. The play ends with Sir Oliver revealing his plot and his findings to Charles and Joseph. Everyone realizes that Lady Sneerwell and her servant Snake orchestrated the rumor about Charles and Lady Teazle. Gossip is perhaps the most central theme of The School for Scandal. Gossip, or rumors, may be true or may be false; in general, however, gossip is spread by both unofficial channels (word-of-mouth) and official channels (newspapers). Since word-of-mouth spreads faster, gossip is mostly spread in the play through that channel, but it is clear from discussions between characters that the spreading of rumors through newspapers has a particular way of spreading information far and making it seem credible. The main rumor spread in the play is that Charles and Lady Teazle are having an affair (spread purposefully by Lady Sneerwell, Joseph, and Snake), but other rumors arise and circulate as well, such as Charles's debt, Joseph and Lady Teazle's affair, and Sir Peter being wounded in a duel. Sir Peter and Lady Teazle are different ages, come from different backgrounds, and seem to have different opinions about how people in the upper class should act; Lady Teazle believes she needs to keep herself integrated by spending money to stay in fashion and taking part in gossiping and judging. Though the couple attempts to be friendly at times, the pressure Lady Teazle feels from society, especially as an outsider, damages their marriage. Interestingly, Sheridan also does not seem to believe that an affair necessarily means the end of a relationship: while the constant arguing in the first half of the play does force the couple to contemplate separation and perhaps drives Lady Teazle to pursue the affair, Sir Peter finding out about this actually gives him hope and confidence that his relationship with his wife may strengthen from her remorse. Gender is an important theme in The School for Scandal, especially as it interacts with other themes of the play such as gossip, marriage, and family. Women in upper-class, 18th-century England were generally viewed as less than men, and were treated as objects. In this play, they play two main roles: daughters and love interests. УСРС ЛЕКЦИЯ 4 1. Thomas Chatterton’s life and creativity Thomas Chatterton (20 November 1752 – 24 August 1770) was an English poet whose precocious talents ended in suicide at age 17. He was an influence on Romantic artists of the period such as Shelley, Keats, Wordsworth and Coleridge. Although fatherless and raised in poverty, Chatterton was an exceptionally studious child, publishing mature work by the age of 11. He was able to pass off his work as that of an imaginary 15th-century poet called Thomas Rowley, chiefly because few people at the time were familiar with medieval poetry, though he was denounced by Horace Walpole. At 17, he sought outlets for his political writings in London, having impressed the Lord Mayor, William Beckford, and the radical leader John Wilkes, but his earnings were not enough to keep him, and he poisoned himself in despair. His unusual life and death attracted much interest among the romantic poets, and Alfred de Vigny wrote a play about him that is still performed today. The oil painting The Death of Chatterton by Pre-Raphaelite artist Henry Wallis has enjoyed lasting fame. After Chatterton's birth (15 weeks after his father's death on 7 August 1752),[2] his mother established a girls' school and took in sewing and ornamental needlework. Chatterton was admitted to Edward Colston's Charity, a Bristol charity school, in which the curriculum was limited to reading, writing, arithmetic and the catechism.[1] From his earliest years, he was liable to fits of abstraction, sitting for hours in what seemed like a trance, or crying for no reason. His lonely circumstances helped foster his natural reserve, and to create the love of mystery which exercised such an influence on the development of his poetry. When Chatterton was age 6, his mother began to recognise his capacity; at age 8, he was so eager for books that he would read and write all day long if undisturbed; by the age of 11, he had become a contributor to Felix Farley's Bristol Journal.[1] His confirmation inspired him to write some religious poems published in that paper. In 1763, a cross which had adorned the churchyard of St Mary Redcliffe for upwards of three centuries was destroyed by a churchwarden. The spirit of veneration was strong in Chatterton, and he sent to the local journal on 7 January 1764 a satire on the parish vandal. He also liked to lock himself in a little attic which he had appropriated as his study; and there, with books, cherished parchments, loot purloined from the muniment room of St Mary Redcliffe, and drawing materials, the child lived in thought with his 15th-century heroes and heroines.[1] The first of his literary mysteries, the dialogue of "Elinoure and Juga," was written before he was 12, and he showed it to Thomas Phillips, the usher at the boarding school Colston's Hospital where he was a pupil, pretending it was the work of a 15th-century poet. Chatterton remained a boarder at Colston's Hospital for more than six years, and it was only his uncle who encouraged the pupils to write. Three of Chatterton's companions are named as youths whom Phillips's taste for poetry stimulated to rivalry; but Chatterton told no one about his own more daring literary adventures. His little pocket-money was spent on borrowing books from a circulating library; and he ingratiated himself with book collectors, in order to obtain access to John Weever, William Dugdale and Arthur Collins, as well as to Thomas Speght's edition of Chaucer, Spenser and other books.[1] At some point he came across Elizabeth Cooper's anthology of verse, which is said to have been a major source for his inventions.[4] Chatterton's "Rowleian" jargon appears to have been chiefly the result of the study of John Kersey's Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, and it seems his knowledge even of Chaucer was very slight. His holidays were mostly spent at his mother's house, and much of them in the favourite retreat of his attic study there. He lived for the most part in an ideal world of his own, in the reign of Edward IV, during the mid-15th century, when the great Bristol merchant William II Canynges (died 1474), five times mayor of Bristol, patron and rebuilder of St Mary Redcliffe "still ruled in Bristol's civic chair." Canynges was familiar to him from his recumbent effigy in Redcliffe church, and is represented by Chatterton as an enlightened patron of art and literature.[5] Badly hurt by Walpole's snub, Chatterton wrote very little for a summer. Then, after the end of the summer, he turned his attention to periodical literature and politics, and exchanged Farley's Bristol Journal for the Town and Country Magazine and other London periodicals. Assuming the vein of the pseudonymous letter writer Junius, then in the full blaze of his triumph, he turned his pen against the Duke of Grafton, the Earl of Bute and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, the Princess of Wales.[15] 2. Robert Burns’ life Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns,[a] was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who have written in the Scots language, although much of his writing is in a "light Scots dialect" of English, accessible to an audience beyond Scotland. He also wrote in standard English, and in these writings his political or civil commentary is often at its bluntest. He is regarded as a pioneer of the Romantic movement, and after his death he became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism, and a cultural icon in Scotland and among the Scottish diaspora around the world. Celebration of his life and work became almost a national charismatic cult during the 19th and 20th centuries, and his influence has long been strong on Scottish literature. In 2009 he was chosen as the greatest Scot by the Scottish public in a vote run by Scottish television channel STV. As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne" is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country. Other poems and songs of Burns that remain well known across the world today include "A Red, Red Rose", "A Man's a Man for A' That", "To a Louse", "To a Mouse", "The Battle of Sherramuir", "Tam o' Shanter" and "Ae Fond Kiss". He had little regular schooling and got much of his education from his father, who taught his children reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and history and also wrote for them A Manual of Christian Belief.[6] He was also taught by John Murdoch (1747–1824), who opened an "adventure school" in Alloway in 1763 and taught Latin, French, and mathematics to both Robert and his brother Gilbert (1760–1827) from 1765 to 1768 until Murdoch left the parish. After a few years of home education, Burns was sent to Dalrymple Parish School in mid-1772 before returning at harvest time to full-time farm labouring until 1773, when he was sent to lodge with Murdoch for three weeks to study grammar, French, and Latin. By the age of 15, Burns was the principal labourer at Mount Oliphant. During the harvest of 1774, he was assisted by Nelly Kilpatrick (1759–1820), who inspired his first attempt at poetry, "O, Once I Lov'd A Bonnie Lass". In 1775, he was sent to finish his education with a tutor at Kirkoswald, where he met Peggy Thompson (born 1762), to whom he wrote two songs, "Now Westlin' Winds" and "I Dream'd I Lay". Despite his ability and character, William Burnes was consistently unfortunate, and migrated with his large family from farm to farm without ever being able to improve his circumstances.[6] At Whitsun, 1777, he removed his large family from the unfavourable conditions of Mount Oliphant to the 130-acre (0.53 km2) farm at Lochlea, near Tarbolton, where they stayed until William Burnes's death in 1784. Subsequently, the family became integrated into the community of Tarbolton. To his father's disapproval, Robert joined a country dancing school in 1779 and, with Gilbert, formed the Tarbolton Bachelors' Club the following year. His earliest existing letters date from this time, when he began making romantic overtures to Alison Begbie (b. 1762). In spite of four songs written for her and a suggestion that he was willing to marry her, she rejected him. Burns's worldly prospects were perhaps better than they had ever been but he alienated some acquaintances by freely expressing sympathy with the French,[31] and American Revolutions, for the advocates of democratic reform and votes for all men and the Society of the Friends of the People which advocated Parliamentary Reform. His political views came to the notice of his employers, to which he pleaded his innocence. Burns met other radicals at the Globe Inn Dumfries. As an Exciseman he felt compelled to join the Royal Dumfries Volunteers in March 1795.[32] He lived in Dumfries in a two-storey red sandstone house on Mill Hole Brae, now Burns Street. The home is now a museum. He went on long journeys on horseback, often in harsh weather conditions as an Excise Supervisor. He was kept very busy doing reports, father of four young children, song collector and songwriter. As his health began to give way, he aged prematurely and fell into fits of despondency.[31] The habits of intemperance (alleged mainly by temperance activist James Currie)[33] are said to have aggravated his long-standing possible rheumatic heart condition.[34] On the morning of 21 July 1796, Burns died in Dumfries, at the age of 37. The funeral took place on Monday 25 July 1796, the day that his son Maxwell was born. He was at first buried in the far corner of St. Michael's Churchyard in Dumfries; a simple "slab of freestone" was erected as his gravestone by Jean Armour, which some felt insulting to his memory.[35] His body was eventually moved to its final location in the same cemetery, the Burns Mausoleum, in September 1817.[36] The body of his widow Jean Armour was buried with his in 1834.[34] 3. Robert Burns’ creativity He made major contributions to George Thomson's A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice as well as to James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum.[citation needed] Arguably his claim to immortality chiefly rests on these volumes, which placed him in the front rank of lyric poets.[20] As a songwriter he provided his own lyrics, sometimes adapted from traditional words. He put words to Scottish folk melodies and airs which he collected, and composed his own arrangements of the music including modifying tunes or recreating melodies on the basis of fragments. In letters he explained that he preferred simplicity, relating songs to spoken language which should be sung in traditional ways. The original instruments would be fiddle and the guitar of the period which was akin to a cittern, but the transcription of songs for piano has resulted in them usually being performed in classical concert or music hall styles.[24] At the 3 week Celtic Connections festival Glasgow each January, Burns songs are often performed with both fiddle and guitar. Thomson as a publisher commissioned arrangements of "Scottish, Welsh and Irish Airs" by such eminent composers of the day as Franz Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven, with new lyrics. The contributors of lyrics included Burns. While such arrangements had wide popular appeal,[25][26][27][28] Beethoven's music was more advanced and difficult to play than Thomson intended.[29][30] Burns also worked to collect and preserve Scottish folk songs, sometimes revising, expanding, and adapting them. One of the better known of these collections is The Merry Muses of Caledonia (the title is not Burns's), a collection of bawdy lyrics that were popular in the music halls of Scotland as late as the 20th century. At Dumfries, he wrote his world famous song "A Man's a Man for A' That", which was based on the writings in The Rights of Man by Thomas Paine, one of the chief political theoreticians of the American Revolution. Burns sent the poem anonymously in 1795 to the Glasgow Courier. He was also a radical for reform and wrote poems for democracy, such as – Parcel of Rogues to the Nation, The Slaves Lament and the Rights of Women. Many of Burns's most famous poems are songs with the music based upon older traditional songs. For example, "Auld Lang Syne" is set to the traditional tune "Can Ye Labour Lea", "A Red, Red Rose" is set to the tune of "Major Graham" and "The Battle of Sherramuir" is set to the "Cameronian Rant". Burns's style is marked by spontaneity, directness, and sincerity, and ranges from the tender intensity of some of his lyrics through the humour of "Tam o' Shanter" and the satire of "Holy Willie's Prayer" and "The Holy Fair".[20] Burns's poetry drew upon a substantial familiarity with and knowledge of Classical, Biblical, and English literature, as well as the Scottish Makar tradition.[41] Burns was skilled in writing not only in the Scots language but also in the Scottish English dialect of the English language. Some of his works, such as "Love and Liberty" (also known as "The Jolly Beggars"), are written in both Scots and English for various effects.[42] His themes included republicanism (he lived during the French Revolutionary period) and Radicalism, which he expressed covertly in "Scots Wha Hae", Scottish patriotism, anticlericalism, class inequalities, gender roles, commentary on the Scottish Kirk of his time, Scottish cultural identity, poverty, sexuality, and the beneficial aspects of popular socialising (carousing, Scotch whisky, folk songs, and so forth).[43] The strong emotional highs and lows associated with many of Burns's poems have led some, such as Burns biographer Robert Crawford,[44] to suggest that he suffered from manic depression—a hypothesis that has been supported by analysis of various samples of his handwriting. Burns himself referred to suffering from episodes of what he called "blue devilism". The National Trust for Scotland has downplayed the suggestion on the grounds that evidence is insufficient to support the claim.[45] Burns is generally classified as a proto-Romantic poet, and he influenced William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Percy Bysshe Shelley greatly. His direct literary influences in the use of Scots in poetry were Allan Ramsay and Robert Fergusson. The Edinburgh literati worked to sentimentalise Burns during his life and after his death, dismissing his education by calling him a "heaven-taught ploughman". Burns influenced later Scottish writers, especially Hugh MacDiarmid, who fought to dismantle what he felt had become a sentimental cult that dominated Scottish literature.