Atrial Fibrillation in the Young: A Neurologist's Nightmare

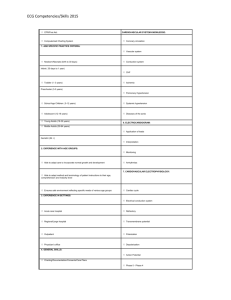

advertisement

Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy ISSN: 1477-9072 (Print) 1744-8344 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ierk20 Atrial fibrillation in young patients Jean-Baptiste Gourraud, Paul Khairy, Sylvia Abadir, Rafik Tadros, Julia Cadrin-Tourigny, Laurent Macle, Katia Dyrda, Blandine Mondesert, Marc Dubuc, Peter G. Guerra, Bernard Thibault, Denis Roy, Mario Talajic & Lena Rivard To cite this article: Jean-Baptiste Gourraud, Paul Khairy, Sylvia Abadir, Rafik Tadros, Julia CadrinTourigny, Laurent Macle, Katia Dyrda, Blandine Mondesert, Marc Dubuc, Peter G. Guerra, Bernard Thibault, Denis Roy, Mario Talajic & Lena Rivard (2018): Atrial fibrillation in young patients, Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy, DOI: 10.1080/14779072.2018.1490644 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14779072.2018.1490644 Accepted author version posted online: 18 Jun 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ierk20 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Journal: Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy DOI: 10.1080/14779072.2018.1490644 Review ip t Atrial fibrillation in young patients cr Jean-Baptiste Gourraud1, Paul Khairy1, 2, Sylvia Abadir2, Rafik Tadros1, Julia Cadrin-Tourigny1, an Thibault1, Denis Roy1, Mario Talajic1 & Lena Rivard1 us Laurent Macle1, Katia Dyrda, Blandine Mondesert1, Marc Dubuc1, Peter G. Guerra1, Bernard 1 Electrophysiology Service, Montreal Heart Institute, Université de Montréal, Montreal M Canada Montreal Canada ed 2 Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Sainte-Justine Hospital, Université de Montréal, ce pt Corresponding author: Lena Rivard MD, MSc. Ac Electrophysiology Service, Montreal Heart Institute, Université de Montréal, Montreal Canada Abstract Introduction: Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most frequent arrhythmia worldwide. While mostly seen in elderly, it can also affect young adults (≤45 years of age), older adolescent and children. ip t Areas covered: The aim of this review is to provide an overview of the current management of AF in young patients. Specific issues arise over diagnostic workup as well as cr antiarrhythmic and anticoagulation therapies. The future management and diagnostic us strategies are also discussed. Expert commentary: Management of AF in the young adult is largely extrapolated from an adult studies and guidelines. In this population, AF could reveal a genetic pathology (e.g. Brugada or Long QT syndrome) or be the initial presentation of a cardiomyopathy. ed pathology M Therefore, thorough workup in the young population to eliminate potential malignant Ac ce pt Key words: atrial fibrillation, children, pediatrics, genetics, management 2 1. Introduction Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia in the adult population, with a projected number of affected patients in the United States exceeding 10 million by 2050 (1, 2). AF is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and ip t appears to be associated with a worse prognostic outcome in patients diagnosed before 30 years of age (3, 4). Although AF predominantly afflicts elderly patients with structural heart cr disease (prevalence >10% after age 80), it can also occur in younger individuals (prevalence us 0.05% before age 30 (3–5). In this population, AF is frequently associated with congenital or structural heart disease. Lone AF (i.e., without underlying cardiomyopathy) is rare (1–4) and guided by studies performed in adults. an its management remains unclear. In the absence of specific guidelines, its management is M In this context, we discuss the current literature on clinical presentation, management options and prognosis of lone AF in young patients. We also explore particular circumstances ed of diagnosis including genetic components, association with inherited ventricular arrhythmia ce pt and supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). Ac 2. Diagnosis Presentation of AF is dependent on age and comorbidities. Beyond the variation in prevalence, age has a strong influence on the type of the first AF episode. While paroxysmal AF is the usual initial presentation in young patients, persistent AF (episodes lasting more than 7 days or requiring cardioversion) and permanent AF (without restoration of sinus rhythm) become predominant after 60 years of age (2, 6, 7). Mills et al. described 42 subjects below age 18 (median age 15.5 years, 83% male) with lone AF in the absence of 3 congenital heart disease, perioperative state, thyroid disease or ventricular preexcitation. The initial episode of AF was considered paroxysmal in >90%, with a median duration of 12 (IQR, 7-24) hours (8). While 21% of the overall population and 40% of patients older than 80 years are ip t asymptomatic, more than 95% of young patients present with symptoms (mostly palpitations and atypical chest pain) at the time of diagnosis (7–9). In the study by Mills et cr al., palpitations and atypical chest pain were described in 85% and 26%, respectively of an with a median duration of 6 (IQR, 1-12) months. us symptomatic patients (8). Previous cardiac symptoms were described in 36% of patients, 3. Etiology and risk factors M Lone AF in young patients remains a diagnosis of exclusion and should be preceded by careful evaluation to rule out an early stage of cardiomyopathy. Workup should evaluate the ce pt ed presence of triggers, predisposing factors and inherited ventricular arrhythmia (Table 1). 3.1 Risk factors Table 2 summarizes main known parameters associated with AF. Ceresnak et al. Ac reported a 61% prevalence of obesity in 18 patients affected with lone AF (mean age 17.9 years, 83% male) (10). This association has been long described in studies of older adults, with a 41% excess risk of AF that increases with body mass index (BMI) (11–13). Smith et al. studied a population-based 36-year cohort study of 12,850 young men who had their BMI measured at their examination for fitness for military service. After a median follow-up of 29 years, the adjusted HR of AF was 2.08 (95% CI 1.48 to 2.92) for overweight men (BMI 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2) and 2.87 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.16) for obese men (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) compared to 4 normal weight men (18.9 to 24.9 kg/m2) (14). In an animal model, sustained obesity results in left atrial dilatation, interstitial atrial fibrosis and atrial electrical remodeling increasing the vulnerability to AF (15). In the Framingham Heart Study, pericardial fat, intra thoracic fat and abdominal visceral fat (assessed by computed tomography) were associated with AF (16). ip t Furthermore, obesity has also been linked to systemic hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea, two additional predisposing factors of AF (11). Although a direct relationship cr between these factors and AF has not been demonstrated, similar cardiovascular effects of us hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea and obesity have been noted in children (below the age of 18), suggesting a potential role in lone AF (17–19). Mah et al. studied 48 patients an (aged ≤22 years) with lone AF and did not find any association between risk of AF recurrence and left atrial dilatation (20). M Excessive participation in endurance sports is a suspected predisposing factor for AF (21, 22). Association with AF seems to increase after 1500 to 2000 lifetime hours of sports ed practice, suggesting a potential threshold effect (23, 24). Indeed, Andersen et al. described a ce pt U shaped association between exercise and AF in young patients (mean age 18.2 years) (24). This reflects the increased risk of AF with a sedentary lifestyle associated with obesity as well as with excess sports. Ac Alcohol intoxication has long been associated with the occurrence of AF, particularly with the practice of binge drinking (25). Several classes of drugs and stimulants could also induce AF (26). In the same report, two additional patients had a history of bronchodilator (albuterol) use at the onset of their AF episodes (8). Identification of predisposing factors for AF could alter management and potentially decrease recurrences (27). However, a recent study in the Framingham cohort concluded that secondary AF also recurs after identification of predisposing factors, with similar long- 5 term AF-related stroke and mortality risks (28). Careful follow-up is essential in young patients given the long-term potential for recurrences and ramifications. 3.2 Familial atrial fibrillation ip t Family history of AF has been reported in 5 to 30% of patients, especially in young patients with lone AF (8). Relatives of an affected family member present with a 40% cr increased risk of arrhythmia occurrence (29, 30). us Contribution of genetic testing has been disappointing since only rare genetic variants were identified in a small number of patients (31–33). Few familial studies using an linkage analysis have succeeded in identifying a genetic variant. Incomplete penetrance, phenotype variability and a complex mode of inheritance could explain this complex M heritability. Finally, rare genetic variations in 36 genes have been associated with AF (34). Some mutations affect sodium and potassium currents (Ikr, Iks, Ik1, Ikur, IkATP, IkAch, Ikur, IAHP, ed If and INa), known to be involved in other inherited arrhythmias. Other mutations affect ce pt cellular electrical coupling, sodium homeostasis, transcription factors and the nuclear envelope (35). However, rare variants in AF concern only a small fraction of patients. In contrast, to account for the missing inheritability of rare variants, genome-wide association Ac studies have identified a total of 15 common genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphism, SNP) linked to AF that could modify the phenotype and identify loci that have been previously linked to cardiac conduction (34, 36). Considering this complex genetic inheritance and the limited diagnostic and prognostic value, routine genetic testing is not currently indicated for lone AF (27). 6 3.2.1 3.2.2 J wave syndromes (Brugada and early repolarization syndrome) In Brugada syndrome (BrS), supraventricular arrhythmias, predominantly AF, are prevalent in 9 to 20% of patients (37–39). Andorin et al. identified a similar rate, 10%, of A ip t supraventricular arrhythmias in 106 children (median age 11 years) with BrS (40). particular aspect of BrS in children is that AF can precede appearance of a BrS pattern on cr ECG (41). The association between AF and an early repolarization pattern has been us demonstrated in several studies, particularly in young athletes (before age 30), but never in children (42). an The link between J wave syndromes and AF is not well understood. A proposed pathophysiological mechanism postulates atrial vulnerability and increased dispersion of M repolarization and refractoriness (43, 44). This hypothesis is supported by the KCNJ8-S422L mutation that has been associated with lone AF, BrS and early repolarization syndrome (45– ed 47). This mutation induces gain of function in ATP-sensitive potassium channel current ce pt leading to shortening of the atrial action potential duration and increased atrial vulnerability (48). As prognosis is poor in untreated patients, it is important to promptly identify BrS Ac underlying apparently lone AF (Figure 1) (40, 49, 50). The use of sodium channel blocker tests remain a matter of debate in children and a baseline ECG should be first performed after cardioversion to rule out underlying BrS (51–54). With appropriate management, the prognosis of BrS has improved in children (40, 49). While quinidine therapy may be of interest in preventing ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias, implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator should be considered in high-risk patients (40, 50, 55). 7 3.2.3 Long QT syndrome Atrial Fibrillation has been reported in 2 to 33% of patients with LQTS (56, 57). In a study of 457 patients (mean age 23) with LQTS (predominantly LQT1), Johnson et al. described that over 60% of patients experience their first episode of AF before the age of 18 ip t year, and before the occurrence of symptoms related to ventricular arrhythmias (56). Further investigations demonstrated that the main genes (KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A) cr associated with LQTS increase the risk of developing AF (58–62). Genetic modifiers in us healthy patients and those with prolonged QT intervals have been associated with an increased risk of early onset of initially presumed lone AF (63, 64). Thus, the same cardiac an ion channel mutations can predispose to both lethal arrhythmias and atrial arrhythmias (65, 66). M Because of an increased risk of lethal arrhythmias, antiarrhythmic drugs that prolong action potential duration should be avoided (55). Kirchhof et al. demonstrated that LQT1 ed patients presented with a prolonged atrial action potential and atrial effective refractory ce pt period (61). This prolongation of atrial action potential could lead to polymorphic atrial tachyarrhythmias (“atrial torsade de pointes”) which appear on ECGs as AF with a longer cycle length (61, 67, 68, Figure 2 ). In contrast, mexiletine may be effective in preventing AF Ac recurrences without increasing the risk of torsade de pointes in LQT1 (69). Once a diagnosis is established and treatment is initiated, life-threatening cardiac events are uncommon in pediatric patients with LQTS (68). Baseline ECGs appear to be a sufficient screening tool to detect LQTS in the pediatric population (70) and careful examination of ECGs using the Bazett formula should be performed after initial detection of AF (71). 8 3.2.4 Short QT syndrome In 2000, Gussak et al. reported the case of a 17 year-old girl with a QTc of 248 ms and AF requiring repeated cardioversion (72) (Figure 3). The authors demonstrated similar ECG changes in a 37- year-old patient who also experienced sudden cardiac death. In a recent ip t report of children with SQTS (25 patients, mean age 15 years), Villafane et al. described previous diagnoses of AF in 4 patients (73). The youngest patient with AF was 4 days old. In us arrhythmias (2) during a median 5.9 years follow-up. cr this population, 8 patients initially experienced sudden cardiac death (6) or life-threatening Both patients had mutations in KCNH2, KCNQ1 and KCNJ2, leading to a gain of an function in potassium channel current that shortened the atrial action potential duration death, and early-onset AF. M and refractoriness (74–77). Patients with SQTS may present with syncope, sudden cardiac Although no medical therapy appears effective and a cardioverter-defibrillator ed implantation is associated with a high incidence of inappropriate shocks, early identification ce pt of SQTS is required because of the high risk of sudden cardiac death (73, 78). 3.3 Cardiomyopathy Ac Rheumatic fever and congenital heart disease are the leading causes of structural heart disease and of AF in the young (79–82). Although heart failure is strongly associated with AF, AF can also occur in the early stages of disease (83, 84). Isolated diastolic dysfunction is associated with an increased occurrence of AF, which could explain the 20% prevalence of AF observed early in the course of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (85–87). However, structural abnormalities can be delayed with respect to occurrence of arrhythmias. Supraventricular arrhythmias are prevalent in 36% of LMNA mutation carriers 9 between the ages of 10-20 years (88). Genetic variants in the SCN5A gene have also been associated with early onset AF (89–91). The association of both AF and conduction system disease suggests the presence of either LMNA or SCN5A mutations even in the absence of dilated cardiomyopathy (92, 93)(Figure 4). Although the clinical impact of these mutations ip t remains controversial, an increased risk of sudden cardiac death has been reported (94, 95). cr 3.4 Supraventricular tachycardia us Several studies have emphasized the association between SVT and AF in young patients(8, 10, 37, 96, 97). Rapid atrial activation during SVT may induce AF. Elimination of an SVT, such as atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT) or atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT), may prevent AF recurrence(98, 99). M Wutzler et al. recently described a series of 124 patients (mean age 29 years) with AF in whom a 57% prevalence of SVT was observed(97). Supraventricular tachycardia was seen in patients without comorbidities. ed mostly In children undergoing an ce pt electrophysiological study after AF occurrence, the prevalence of SVT has been estimated to be 30-39%(8, 10). Atrial Fibrillation is of specific concern in Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome Ac that manifests as ventricular preexcitation with palpitations suggestive of AVRT. Because of the risk of ventricular fibrillation related to rapidly conducting anterograde accessory pathways (Figure 5), patients with AF or short anterograde refractory periods (<250 ms) should be offered catheter ablation (100, 101). Ventricular fibrillation is rare in patients with WPW syndrome occurring in only 1.5 per 1000 patient/years of follow up whereas AF occurs in more than one third of patients (102, 103). In addition to SVT, other proposed pathophysiological mechanisms to account for the high prevalence of AF in patients with 10 WPW syndrome include atrial vulnerability, increased dispersion of repolarization and refractoriness, and eccentric atrial activation due to retrograde conduction across the accessory pathway (104–106). Slow-pathway or accessory-pathway ablation has an impact on recurrent AF, with ip t Sciarra et al. demonstrating a 7.7% recurrence rate in 257 patients (mean age 29 years) after a 21-month follow-up, consistent with findings from Haïssaguerre et al. (98, 107). Pediatric cr cases reports further corroborate these findings and suggests that ablating SVT could reduce us the need for pharmacological therapy and more extensive AF ablation procedures (8, 10, 96, an 97). 4 Management issues M Management of AF involves two main aspects: symptoms and prevention of thromboembolism. Although no specific data addressing this in the young are available, ce pt ed issues specific to a young population should be considered (27). 4.1 Acute management The patient’s initial clinical status should determine the initial management. Ac Hemodynamically unstable patients should receive prompt cardioversion (1–2 J/kg) (27). Acute non-cardiac conditions associated with AF (e.g., hypertension, hyperthyroidism, pulmonary embolism, viral infections, and sepsis) should be identified and treated. For other patients, the decision to restore sinus rhythm or slow ventricular rate should be individualized. In hemodynamically stable patients, a rate control strategy can be initiated depending on ventricular rate response and symptoms. When rapid rate control is required, 11 intravenous administration of a beta-blocker (e.g., esmolol, propranolol, and metoprolol) should be considered over a nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, amiodarone or digoxin given the shorter time to effect.(108, 109). Intravenous amiodarone is generally reserved for critically ill infants since it is associated with an increased rate of adverse events ip t in this population (110). Because of a negative inotropic effect, intravenous nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers should not be used as first-line therapy for cr rate control (111). us In patients with pre-excitation, intravenous medication (preferably class I AAD) or electrical cardioversion should be considered in emergency situations. Because of the an increased risk of ventricular fibrillation, amiodarone, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers M and digoxin should be avoided in these cases (27). 4.2 Rate and rhythm control ed For rhythm control, preferential pharmacological agents are class IA (e.g., ce pt procainamide), class IC drugs (e.g., flecainide and propafenone), and some class III antiarrhythmic drugs (e.g., ibutilide and dofetilide) (27). There is a paucity of data regarding safety and efficacy of class III AADs, such that their use in children should be limited. While Ac amiodarone is the most effective AAD for the maintenance of sinus rhythm, it is less effective for acute cardioversion (112). Following the acute management phase, the objective of rhythm control is to prevent symptomatic recurrences of AF. Large clinical studies have not revealed superiority of rhythm control over a rate control strategy (113). However some evidence shows improved quality of life when sinus rhythm can be maintained (114, 115). Benefits of AADs appear to be offset by their adverse effects which include proarrhythmia for all but amiodarone, 12 flecainide, propafenone and dronedarone, and increased mortality for quinidine, disopyramide and sotalol (116). Current guidelines recommend beta blockers, propafenone or flecainide as first-line therapy for lone AF (27). In recent years, catheter ablation targeting pulmonary vein triggers is increasingly ip t used for rhythm control (117,118) . In a recent study, Saguner et al. reported 85 young adults (mean age 31±4 years; 69% men) who underwent pulmonary vein isolation for cr paroxysmal (N=52) or persistent AF (N=33). After a median follow-up of 4.6 years (IQR: 2.6- us 6.6) and a mean of 1.50±0.6 procedures, 84% patients remained in sinus rhythm. Structural heart disease and obesity independently predict AF recurrence (119). In children, pulmonary an vein ablation procedures have been successfully achieved with cryothermal and radiofrequency energy (8, 120–123). There is no clear evidence of one approach being M superior to the other (8, 120–123). In general, the efficacy of catheter ablations appears to be higher in young patients, at the early stage of AF disease (124, 125). In 1548 consecutive ed patients who underwent 2038 AF ablation procedures. Leong Sit et al. compared major ce pt procedure complications and efficacy according to age in four groups : <45 years (group 1), 45 to 54 years (group 2), 55 to 64 years (group 3), and ≥65 years (group 4). Off antiarrhythmic drugs, 76% patients in group 1 were free of AF after a mean follow-up of 36 Ac months compared to 68 % (mean FU of 28 months), 65 % (mean FU 28 months) and 55% (mean FU of 28 months) of patients in groups 2, 3 and 4, respectively (P<0.001) (125). However, considering the risks involved, it appears reasonable to limit catheter ablations to symptomatic children and young adults with recurrent AF (126). Additionally, while catheter ablations may be appropriate in older adolescents, such procedures should be carefully discussed in children because of the marked enlargement of lesions over time in immature 13 hearts (127). Minimally invasive epicardial ablation has also been reported in a child with Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t lone AF (128). 14 4.3 Prevention of thromboembolism Increased risk of stroke, morbidity and mortality associated with AF is well established in adults (4, 27, 129, 130). Strokes resulting from AF are associated with increased mortality and worse functional outcomes (131). Although age appears to be ip t associated with more extensive AF-related strokes, young patients are also subject to poor clinical outcomes (6, 132). In the pediatric multicenter Canadian study on lone AF, cr intracradiac thrombi were present in 5% of the population in whom one presented with a us cerebral ischemic event (8). Cardioversion for AF <48 hours in duration may be performed without prior an anticoagulation in patients with a low risk of stroke (i.e., no valvular heart disease, no risk factors for thromboembolism, rheumatic heart disease, or mechanical valves). If duration is M >48 hours or unknown, or if risk factors for thromboembolism are present, anticoagulation should be pursued for 3 weeks prior to cardioversion or, alternatively, transesophageal ed echography can be performed to rule out intracardiac thrombi (27). Whatever the context ce pt (i.e. low/high risk of thromboembolism, emergency/delayed cardioversion) and the technique used (i.e. pharmacological or electrical cardioversion), at least 4 weeks of anticoagulation is recommended following cardioversion (27). Although these guidelines Ac address adults, the high prevalence of thrombus observed in children with lone AF is similar to adults, suggesting that similar considerations are applicable to children in preventing thromboembolic complications (8, 133, 134). Nuotio et al. showed that in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc [Congestive Heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 (double), Diabetes, and prior Stroke or TIA (double), Vascular disease, Age 65–74, and Sex (female ) < 2, stroke or TIA after cardioversion occurred in up to 0.9% within 30 days after cardioversion if no anticoagulation was administered after the procedure (135). 15 The CHADS2 [Congestive Heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75, Diabetes, and prior Stroke or TIA (double)] or CHA2DS2-VASc risk scores)] is recommended to guide long-term anticoagulation decisions (27, 136). Based on large observational studies, the threshold to ip t initiate OAC has been lowered in patients older than 65 years of age and men with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 and a score of 2 for women (27, 137). This threshold could even be cr reduced further with the safer profile of NOACs. While no such score has been validated in us children, studies in populations with congenital heart disease suggest that these scores are low in young populations and insensitive to guide thromboprophylactic therapy (8, 138). an Subclinical stroke appears to occur early in the clinical course of AF, even with a CHADS2 score of 0-1 (139). The benefits of anticoagulant therapy for subclinical stroke and silent M cerebral ischemia have yet to be assessed. Pending the results of studies such as the BRAINAF trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02387229), no thromboprophylaxis is recommended for young ce pt ed patients without risk factors for stroke. 5. Conclusion Despite its scarcity, diagnosis of lone AF in young patients is essential considering Ac that associated morbidity and mortality may be substantially reduced with appropriate therapy. As symptoms are usually non-specific, diagnosis remains a challenge and often requires repeat or long-term ECG monitoring. Lone AF typically presents in association with SVT during adolescence. However, inherited arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy should always be investigated. Lone AF remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Identification of associated diseases considerably alters prognosis and therapy. The management of lone AF is largely individualized and guided by the adult 16 literature. While rhythm control with AADs appears reasonable in patients with growing myocardium, catheter ablation may be an alternative for symptomatic older adolescents. Many questions remain unresolved, including accurate estimations of thromboembolic risk ip t in children. 6. Expert commentary cr Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia in older adults but, in the absence of us structural heart disease is rare in pediatric, teenagers and young adult patients. Prevalence of AF has been estimated to 0.05% in patients younger than 30 years of age compared to an 10% in patients older than 80. A family history of AF is more often present in young patients. Genetic testing has been disappointing and is not done in clinical practice. Management of M AF in this younger population is largely extrapolated from adult studies and guidelines but is associated with the need of a specific workup. Indeed, the workup should rule out the ed presence of a genetic pathology, a re-entrant tachycardia (atrioventricular nodal reentrant ce pt tachycardia or atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia) or predisposing factors such as obesity, alcohol or drug use or strenuous exercise. Obesity has also been linked to sleep apnea, diabetes and hypertension in this young population. Long-term practice of strenuous Ac endurance exercise (cycling, cross country skiing or marathon running) has been associated with an increased risk of paroxysmal AF in otherwise healthy young adults. Sport reduction or abstinence have shown a reduction in AF episodes. Furthermore, in this young population, AF could reveal a genetic disease with direct consequences on AF management and medication since the use of antiarrhythmic class I in Brugada syndrome and the use of antiarrhythmic class III in Long QT syndrome could trigger malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Other genetic diseases like short QT and anterior 17 repolarization syndrome have also been associated with an increased risk of AF (present in up to 30% of patients). Atrial fibrillation could also be the initial presentation of a cardiomyopathy, in particular laminopathy. A long-term follow-up is recommended. However, younger patients tend to be more symptomatic and less-willing to take ip t long-term medication. An electrophysiological study could be useful to rule-out a reentrant tachycardia which can trigger AF and for which ablation could reduce the risk of AF cr recurrence. In young adults, AF catheter ablation is associated with a lower complication us rate, shorter hospitalizations and a higher success rate when compared to older patients. As in the older patients, the CHA2DS2-VASc [Congestive Heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 an (double), Diabetes, and prior Stroke or TIA (double), Vascular disease, Age 65–74, and Sex (female) and stroke or TIA(double)] is used to stratify stroke risk and in the absence of other factor (i.e., hypertension, diabetes, stroke M risk or TIA or vascular disease) thromboprophylaxis is not recommended for young patients with lone AF. But in children, ed teenager and young adults, stroke is associated to a poorer clinical outcome when compared ce pt to older patients. If AF lasts longer than 48 hours, transoesophageal echography or 4-weeks of anticoagulation therapy is recommended prior to cardioversion with anticoagulation continuing for 4 weeks following the cardioversion. Ac AF remains rare in young patients and lone AF remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Usual AF guidelines apply. In the future, controlled randomized trials and large registry data are much needed to develop specific guidelines in this young AF population. 7. Five-year view Genetic testing should be done in clinical practice to help differentiate lone AF, channelopathy or cardiomyopathy. Antiarrhythmic therapy should be personalized. Atrial 18 ablation should be done as first-line therapy and anticoagulation therapy should be initiated at a younger age. Key issues Lone atrial fibrillation is rare in subjects younger than 30 years and an ip t • underlying cause should be ruled out. cr Patients with Long QT, Short QT and Brugada syndrome are at a higher risk of developing AF. • Ablation of atrial fibrillation appears to be effective in this population with a an one-year success rate > 70%. Atrial fibrillation could be induced by SVT. SVT ablation decreases the risk of Ac ce pt ed AF recurrence. M • us • 19 Funding This paper was not funded. ip t Declaration of interest L Rivard is the principal Investigator of the BRAIN AF trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02387229) cr and received salary support from the Fonds de Santé en recherche du Québec (FRSQ). This us research did not receive any specific grant. The authors have no other relevant affiliations an or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from Ac ce pt ed relationships to disclose. M those disclosed. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other 20 References Papers of special note have been highlighted as: * of interest ** of considerable interest Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t 1. Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation 2006;114:119–25 2. Kopecky SL, Gersh BJ, McGoon MD, et al. The natural history of lone atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine 1987;317:669–74* This study describes the natural history of AF in 3623 patients and the risk of stroke after a mean follow-up of 15 years. 3. Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2004;110:1042–6 ** This study reports the risk of developing AF in patients from the Framingham Heart Study who were free of AF at the index age of 40 years. The lifetime risk of developing AF in those without known cardiomyopathy was estimated at 16%. 4. Rutten-Jacobs LCA, Arntz RM, Maaijwee NAM, et al. Long-term mortality after stroke among adults aged 18 to 50 years. JAMA 2013;309:1136–44 5. Wilke T, Groth A, Mueller S, et al. Incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation: an analysis based on 8.3 million patients. Europace 2013;15:486–93 6. Šaňák D, Hutyra M, Král M, et al. Atrial fibrillation in young ischemic stroke patients: an underestimated cause? Eur. Neurol. 2015;73:158–63 7. Kerr CR, Humphries KH, Talajic M, et al. Progression to chronic atrial fibrillation after the initial diagnosis of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: results from the Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. Am. Heart J. 2005;149:489–96 8. Mills LC, Gow RM, Myers K, et al. Lone atrial fibrillation in the pediatric population. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2013;29:1227–33 9. Sankaranarayanan R, Kirkwood G, Dibb K, et al. Comparison of atrial fibrillation in the young versus that in the elderly: a review. Cardiol Res Pract 2013;2013. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3564268/. Accessed February 17, 2016. 10. Ceresnak SR, Liberman L, Silver ES, et al. Lone atrial fibrillation in the young - perhaps not so “lone”? J. Pediatr. 2013;162:827–31 11. Gami AS, Hodge DO, Herges RM, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2007;49:565–71** This retrospective cohort study of 3542 patients referred for an initial diagnostic polysomnogram showed that obesity and the magnitude of nocturnal desaturation are independant risk factors of AF. 12. Foy AJ, Mandrola J, Liu G, et al. Relation of Obesity to New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter in Adults. Am. J. Cardiol. 2018;121:1072-5 13. Shulman E, Chudow JJ, Shah T, et al. Relation of Body Mass Index to development of atrial fibrillation in hispanics, blacks, and non-Hispanic whites. Am. J. Cardiol. 2018;121:1177–81 14. Schmidt M, Bøtker HE, Pedersen L, et al. Comparison of the frequency of atrial fibrillation in young obese versus young nonobese men undergoing examination for fitness for military 21 Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t service. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014;113:822–6 15. Mahajan R, Lau DH, Brooks AG, et al. Electrophysiological, electroanatomical, and structural remodeling of the atria as consequences of sustained obesity. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015;66:1–11 16. Lee JJ, Yin X, Hoffmann U, et al. Relation of pericardial fat, intrathoracic fat, and abdominal visceral fat with incident atrial fibrillation (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2016;118:1486–92 17. Evans CA, Selvadurai H, Baur LA, et al. Effects of obstructive sleep apnea and obesity on exercise function in children. Sleep 2014;37:1103–10 18. Sorof J, Daniels S. Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions. Hypertension 2002;40:441–7 * This article describes consequences of obesity in children and adolescents. 19. Amin R, Somers VK, McConnell K, et al. Activity-adjusted 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure and cardiac remodeling in children with sleep disordered breathing. Hypertension 2008;51:84–91 20. Mah DY, Shakti D, Gauvreau K, et al. Relation of left atrial size to atrial fibrillation in patients aged ≤22 Years. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017;119:52–6 21. Karjalainen J, Kujala UM, Kaprio J, et al. Lone atrial fibrillation in vigorously exercising middle aged men: case-control study. BMJ 1998;316:1784–5 22. Molina L, Mont L, Marrugat J, et al. Long-term endurance sport practice increases the incidence of lone atrial fibrillation in men: a follow-up study. Europace 2008;10:618–23 23. Elosua R, Arquer A, Mont L, et al. Sport practice and the risk of lone atrial fibrillation: a case-control study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2006;108:332–7 24. Andersen K, Rasmussen F, Held C, et al. Exercise capacity and muscle strength and risk of vascular disease and arrhythmia in 1.1 million young Swedish men: cohort study. BMJ 2015;351 25. Mukamal KJ, Tolstrup JS, Friberg J, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of atrial fibrillation in men and women: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation 2005;112:1736–42 26. Van der Hooft CS, Heeringa J, van Herpen G, et al. Drug-induced atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2004;44:2117–24 27. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. Heart J. 2016;37:2893–962 ** This expert consensus summarizes appropriate workup and management in patients with AF. 28. Lubitz SA, Yin X, Rienstra M, et al. Long-term outcomes of secondary atrial fibrillation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2015;131:1648–55* This study shows that long-term AF-related stroke and mortality risks were similar among individuals with and without secondary AF precipitants. 29. Lubitz SA, Yin X, Fontes JD, et al. Association between familial atrial fibrillation and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA 2010;304:2263–9 30. Fox CS, Parise H, D’Agostino, et al. Parental atrial fibrillation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in offspring. JAMA 2004;291:2851–5* This study reports that parental AF increases the future risk for offspring AF. 31. Brugada R, Tapscott T, Czernuszewicz GZ, et al. Identification of a genetic locus for familial atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:905–11* The authors described a family of 26 members of whom 10 had atrial fibrillation which segregated as an autosomal dominant disease. 32. Chen Y-H, Xu S-J, Bendahhou S, et al. KCNQ1 gain-of-function mutation in familial atrial 22 Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t fibrillation. Science 2003;299:251–4 33. Yang Y, Xia M, Jin Q, et al. Identification of a KCNE2 gain-of-function mutation in patients with familial atrial fibrillation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:899–905 34. Christophersen IE, Ellinor PT. Genetics of atrial fibrillation: from families to genomes. J Hum Genet 2015. Available at: http://www.nature.com/jhg/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/jhg201544a.html. Accessed December 10, 2015 35. Ye J, Tucker NR, Weng L-C, et al. A functional variant associated with atrial fibrillation regulates PITX2c expression through TFAP2a. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;99:1281–91 36. Nielsen JB, Fritsche LG, Zhou W, et al. Genome-wide study of atrial fibrillation identifies seven risk loci and highlights biological pathways and regulatory elements involved in cardiac development. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;102:103–15 37. Giustetto C, Cerrato N, Gribaudo E, et al. Atrial fibrillation in a large population with Brugada electrocardiographic pattern: prevalence, management, and correlation with prognosis. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:259–65 38. Bordachar P, Reuter S, Garrigue S, et al. Incidence, clinical implications and prognosis of atrial arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome. Eur. Heart J. 2004;25:879–84 39. Sacher F, Probst V, Maury P, et al. Outcome after implantation of a cardioverterdefibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: a multicenter study-part 2. Circulation 2013;128:1739–47 * The authors report the outcome of 378 patients with Brugada syndrome implanted with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. 40. Andorin A, Behr ER, Denjoy I, et al. The impact of clinical and genetic findings on the management of young Brugada syndrome patients. Heart Rhythm 2016. 41. Einbinder T, Lowenthal A, Fogelman R. Ventricular fibrillation storm in a child. Europace 2014;16:1654 42. Stumpf C, Simon M, Wilhelm M, et al. Left atrial remodeling, early repolarization pattern, and inflammatory cytokines in professional soccer players. Journal of Cardiology. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0914508715002713. Accessed March 16, 2016. 43. Francis J, Antzelevitch C. Atrial fibrillation and Brugada syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;51:1149–53 44. Choi K-J, Kim J, Kim S-H, et al. Increased dispersion of atrial repolarization in Brugada syndrome. Europace 2011;13:1619–24 45. Barajas-Martínez H, Hu D, Ferrer T, et al. Molecular genetic and functional association of Brugada and early repolarization syndromes with S422L missense mutation in KCNJ8. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:548–55 46. Haïssaguerre M, Chatel S, Sacher F, et al. Ventricular fibrillation with prominent early repolarization associated with a rare variant of KCNJ8/KATP channel. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 2009;20:93–98 47. Delaney JT, Muhammad R, Blair MA, et al. A KCNJ8 mutation associated with early repolarization and atrial fibrillation. Europace 2012;14:1428–32 48. Medeiros-Domingo A, Tan B-H, Crotti L, et al. Gain-of-function mutation S422L in the KCNJ8-encoded cardiac KATP channel Kir6.1 as a pathogenic substrate for J-wave syndromes. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:1466–71 49. Probst V, Denjoy I, Meregalli PG, et al. Clinical aspects and prognosis of Brugada syndrome in children. Circulation 2007;115:2042–8 50. Gourraud J-B, Barc J, Thollet A, et al. Brugada syndrome: Diagnosis, risk stratification and 23 Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t management. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017;110:188–95 51. Conte G, Dewals W, Sieira J, et al. Drug-induced brugada syndrome in children: clinical features, device-based management, and long-term follow-up. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2272–9 52. Sorgente A, Sarkozy A, De Asmundis C, et al. Ajmaline challenge in young individuals with suspected Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011;34:736–41 53. Therasse D, Sacher F, Petit B, et al. Sodium-channel blocker challenge in the familial screening of Brugada syndrome: Safety and predictors of positivity. Heart Rhythm 2017. 54. Therasse D, Sacher F, Babuty D, et al. Value of the sodium-channel blocker challenge in Brugada syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017;245:178–80 55. Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS Expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:1932–63** This expert consensus summarizes appropriate workup and management in patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes. 56. Johnson JN, Tester DJ, Perry J, et al. Prevalence of early-onset atrial fibrillation in congenital long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2008;5:704–709.* This study reports the prevalence of AF in Long QT syndromes. 57. Zellerhoff S, Pistulli R, Mönnig G, et al. Atrial arrhythmias in long-QT syndrome under daily life conditions: a nested case control study. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2009;20:401– 7 58. Benito B, Brugada R, Perich RM, et al. A mutation in the sodium channel is responsible for the association of long-QT syndrome and familial atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2008;5:1434–40 59. Olesen MS, Yuan L, Liang B, et al. High prevalence of long-QT syndrome-associated SCN5A variants in patients with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2012;5:450–9 60. Robaei D, Ford T, Ooi S-Y. Ankyrin-B syndrome: a case of sinus node dysfunction, atrial fibrillation and prolonged QT in a young adult. Heart Lung Circ 2015;24:e31-34. 61. Kirchhof P, Eckardt L, Franz MR, et al. Prolonged atrial action potential durations and polymorphic atrial tachyarrhythmias in patients with long-QT syndrome. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 2003;14:1027–33 62. Schott J-J, Charpentier F, Peltier S, et al. Mapping of a gene for long QT syndrome to chromosome 4q25-27. Am J Hum Genet 1995;57:1114–22 63. Andreasen L, Nielsen JB, Christophersen IE, et al. Genetic modifier of the QTc interval associated with early-onset atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:1234–40 64. Mandyam MC, Soliman EZ, Alonso A, et al. The QT interval and risk of incident atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:1562–8 65. Zareba W, Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ, et al. Influence of genotype on the clinical course of the long-QT syndrome. International Long-QT Syndrome Registry Research Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:960–5 66. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-QT syndrome: gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias. Circulation 2001;103:89– 95. 67. Kirchhof P, Eckardt L, Mönnig G, et al. A patient with “atrial torsades de pointes.” J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2000;11:806–11 24 Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t 68. Koponen M, Marjamaa A, Hiippala A, et al. Follow-Up of 316 molecularly defined pediatric long-QT syndrome patients clinical course, treatments, and side effects. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:815–23 69. El Yaman M, Perry J, Makielski JC, et al. Suppression of atrial fibrillation with mexiletine pharmacotherapy in a young woman with type 1 long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2008;5:472–4 70. Rodday AM, Triedman JK, Alexander ME, et al. Electrocardiogram screening for disorders that cause sudden cardiac death in asymptomatic children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2012;129:e999-1010. 71. Phan DQ, Silka MJ, Lan Y-T, et al. Comparison of formulas for calculation of the corrected QT interval in infants and young children. J. Pediatr. 2015;166:960-964.e1–2. 72. Gussak I, Brugada P, Brugada J, et al. Idiopathic short QT interval: a new clinical syndrome? Cardiology 2000;94:99–102. 73. Villafañe J, Atallah J, Gollob MH, et al. Long-term follow-up of a pediatric cohort with short QT syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:1183–91 74. Schimpf R, Borggrefe M, Wolpert C. Clinical and molecular genetics of the short QT syndrome. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2008;23:192–8 75. Hong K, Piper DR, Diaz-Valdecantos A, et al. De novo KCNQ1 mutation responsible for atrial fibrillation and short QT syndrome in utero. Cardiovascular Research 2005;68:433–40 76. Hong K, Bjerregaard P, Gussak I, et al. Short QT Syndrome and atrial fibrillation caused by mutation in KCNH2. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 2005;16:394–6 77. Priori SG, Pandit SV, Rivolta I, et al. A novel form of short QT syndrome (SQT3) is caused by a mutation in the KCNJ2 gene. Circ. Res. 2005;96:800–7 78. Giustetto C, Di Monte F, Wolpert C, et al. Short QT syndrome: clinical findings and diagnostic-therapeutic implications. Eur. Heart J. 2006;27:2440–7 79. Steer AC, Carapetis JR. Prevention and treatment of rheumatic heart disease in the developing world. Nat Rev Cardiol 2009;6:689–98 80. Saxena A, Ramakrishnan S, Roy A, et al. Prevalence and outcome of subclinical rheumatic heart disease in India: the RHEUMATIC (Rheumatic Heart Echo Utilisation and Monitoring Actuarial Trends in Indian Children) study. Heart 2011;97:2018–22 81. Mondésert B, Abadir S, Khairy P. Arrhythmias in adult congenital heart disease: the year in review. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2013;28:354–9 82. Khairy P, Aboulhosn J, Gurvitz MZ, et al. Arrhythmia burden in adults with surgically repaired tetralogy of Fallot: a multi-institutional study. Circulation 2010;122:868–75 83. Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, et al. Prevalence, incidence, prognosis, and predisposing conditions for atrial fibrillation: population-based estimates 1. The American Journal of Cardiology 1998;82:2N-9N. 84. Maisel WH, Stevenson LW. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and rationale for therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003;91:2D-8D. 85. Olivotto I, Cecchi F, Casey SA, et al. Impact of Atrial Fibrillation on the Clinical Course of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2001;104:2517–24 86. Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Bellone P, et al. Clinical profile of stroke in 900 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2002;39:301– 7* This study shows a significantly higher risk of stroke and embolic events in nonanticoagulated patients suffering from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation compared to patients receiving warfarin. 87. Rosenberg MA, Gottdiener JS, Heckbert SR, et al. Echocardiographic diastolic parameters 25 Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t and risk of atrial fibrillation: the Cardiovascular Health Study. European Heart Journal 2012;33:904–12 88. Van Berlo JH, de Voogt WG, van der Kooi AJ, et al. Meta-analysis of clinical characteristics of 299 carriers of LMNA gene mutations: do lamin A/C mutations portend a high risk of sudden death? J. Mol. Med. 2005;83:79–83 89. Amin AS, Bhuiyan ZA. SCN5A mutations in atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:1870–1 90. Olesen MS, Andreasen L, Jabbari J, et al. Very early-onset lone atrial fibrillation patients have a high prevalence of rare variants in genes previously associated with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:246–51 91. Ilkhanoff L, Arking DE, Lemaitre RN, et al. A common SCN5A variant is associated with PR interval and atrial fibrillation among African Americans. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2014;25:1150–7 92. Parks SB, Kushner JD, Nauman D, et al. Lamin A/C mutation analysis in a cohort of 324 unrelated patients with idiopathic or familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. Heart J. 2008;156:161–9 93. McNair WP, Ku L, Taylor MRG, et al. SCN5A mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, conduction disorder, and arrhythmia. Circulation 2004;110:2163–7 94. Van Rijsingen IAW, Arbustini E, Elliott PM, et al. Risk factors for malignant ventricular arrhythmias in lamin A/C mutation carriers a European cohort study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;59:493–500 95. Hasselberg NE, Edvardsen T, Petri H, et al. Risk prediction of ventricular arrhythmias and myocardial function in Lamin A/C mutation positive subjects. Europace 2014;16:563–71 96. Strieper MJ, Frias P, Fischbach P, et al. Catheter ablation of primary supraventricular tachycardia substrate presenting as atrial fibrillation in adolescents. Congenital Heart Disease 2010;5:465–9 97. Wutzler A, von Ulmenstein S, Attanasio P, et al. Where There’s Smoke, There’s Fire? Significance of Atrial Fibrillation in Young Patients. Clin Cardiol 2016:n/a-n/a. 98. Sciarra L, Rebecchi M, Ruvo ED, et al. How many atrial fibrillation ablation candidates have an underlying supraventricular tachycardia previously unknown? Efficacy of isolated triggering arrhythmia ablation. Europace 2010;12:1707–12 99. Weiss R, Knight BP, Bahu M, et al. Long-term follow-up after radiofrequency ablation of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in patients with tachycardia-induced atrial fibrillation. The American Journal of Cardiology 1997;80:1609–10* 100. Cohen MI, Triedman JK, Cannon BC, et al. PACES/HRS Expert Consensus Statement on the Management of the Asymptomatic Young Patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, Ventricular Preexcitation) Electrocardiographic Pattern: Developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS). Heart Rhythm 2012;9:1006–24 ** A comprehensive consensus statement that summarizes appropriate workup and management in patients with a Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. 101. Klein GJ, Bashore TM, Sellers TD, et al. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-ParkinsonWhite syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979;301:1080–1085.* This study shows that the risk of ventricular fibrillation in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome was linked to the presence of atrial fibrillation, reciprocating tachycardia, and rapid conduction over an accessory pathway during atrial fibrillation and multiple accessory pathways. 26 Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t 102. Sharma AD, Klein GJ, Guiraudon GM, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with WolffParkinson-White syndrome: incidence after surgical ablation of the accessory pathway. Circulation 1985;72:161–9 103. Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953-1989. Circulation 1993;87:866–73 104. Centurión OA, Shimizu A, Isomoto S, et al. Mechanisms for the genesis of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in the Wolff Parkinson-White syndrome: intrinsic atrial muscle vulnerability vs. electrophysiological properties of the accessory pathway. Europace 2008;10:294–302 105. Hamada T, Hiraki T, Ikeda H, et al. Mechanisms for atrial fibrillation in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2002;13:223–9 106. Iesaka Y, Yamane T, Takahashi A, et al. Retrograde multiple and multifiber accessory pathway conduction in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: potential precipitating factor of atrial fibrillation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 1998;9:141–51 107. Haissaguerre M, Fischer B, Labbé T, et al. Frequency of recurrent atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation of overt accessory pathways. Am. J. Cardiol. 1992;69:493–7*The authors demonstrated that in patients with AVRT and AF ,radiofrequency procedure of accessory pathways can prevent AF recurrence 108. Jordaens L, Trouerbach J, Calle P, et al. Conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm and rate control by digoxin in comparison to placebo. European Heart Journal 1997;18:643– 8 109. Ramusovic S, Läer S, Meibohm B, et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous amiodarone in children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013;98:989–93 110. Saul JP, Scott WA, Brown S, et al. Intravenous amiodarone for incessant tachyarrhythmias in children: A randomized, double-blind, antiarrhythmic drug trial. Circulation 2005;112:3470–7 * A double-blind, randomized, multicenter, dose-response study on the safety and efficacy of intravenous amiodarone in children. 111. Wiesfeld AC, Remme WJ, Look MP, et al. Acute hemodynamic and electrophysiologic effects and safety of high-dose intravenous diltiazem in patients receiving metoprolol. Am. J. Cardiol. 1992;70:997–1003 112. Freemantle N, Lafuente-Lafuente C, Mitchell S, et al. Mixed treatment comparison of dronedarone, amiodarone, sotalol, flecainide, and propafenone, for the management of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2011;13:329–45 113. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:1825–33** This landmark study shows that a rhythm-control strategy (through antiarrhythmic drugs) offers no survival advantages over the rate-control strategy in patients suffering from AF. 114. Corley SD, Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, et al. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Study. Circulation 2004;109:1509–13* In this sub-study of AFFIRM, the authors show that the presence of sinus rhythm was associated with a lower risk of death, as was warfarin use. 115. Suman-Horduna I, Roy D, Frasure-Smith N, et al. Quality of life and functional capacity in patients with atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:455–60 116. Lafuente-Lafuente C, Valembois L, Bergmann J-F, et al.. Antiarrhythmics for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 27 Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t 2015;3:CD005049. 117. Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. New England Journal of Medicine 1998;339:659–66.** In this landmark study, Haïssaguerre et al. show, for the first time, that AF is initiated by triggers originating from the pulmonary veins. 118. Andrade JG, Macle L, Nattel S, et al. Contemporary Atrial Fibrillation Management: A Comparison of the Current AHA/ACC/HRS, CCS, and ESC Guidelines.Can J Cardiol. 2017 Aug; 33:965-76 119. Saguner AM, Maurer T, Wissner E, et al.Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in very young adults: a 5-year follow-up study.Europace. 2018 Jan 1;20:58-64 120. Kato Y, Horigome H, Takahashi-Igari M, et al.. Isolation of pulmonary vein and superior vena cava for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in a young adult with left ventricular noncompaction. Europace 2010;12:1040–1 121. Conte G, Chierchia G-B, Levinstein M, et al. Ice vs. fire: cryoballoon ablation for the prevention of inappropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks in a 14-year-old girl with Brugada syndrome. Europace 2013;15:1804 122. Nanthakumar K, Lau YR, Plumb VJ, et al. Electrophysiological findings in adolescents with atrial fibrillation who have structurally normal hearts. Circulation 2004;110:117–23 123. Balaji S, Kron J, Stecker EC. Catheter ablation of recurrent lone atrial fibrillation in teenagers with a structurally normal heart. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology 2016;39:60–4 124. Leong-Sit P, Zado E, Callans DJ, et al. Efficacy and risk of atrial fibrillation ablation before 45 years of age. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010;3:452–457.* This study shows that, in patients younger than 45 years, catheter ablation is associated with a lower major complication rate and a comparable efficacy rate of AF . 125. Zhang X-D, Gu J, Jiang W-F, et al. The impact of age on the efficacy and safety of catheter ablation for long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation. International Journal of Cardiology 2013;168:2693–8 126. Wasmer K, Breithardt G, Eckardt L. The young patient with asymptomatic atrial fibrillation: what is the evidence to leave the arrhythmia untreated? Eur. Heart J. 2014;35:1439–47 127. Khairy P, Guerra PG, Rivard L, et al. Enlargement of catheter ablation lesions in infant hearts with cryothermal versus radiofrequency energy: an animal study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4:211–7* This study shows that cryothermal lesions were associated with less thrombogen risk but identical enlargement when compared to radiofrequency lesions. 128. Nasso G, Bonifazi R, Fiore F, et al. Minimally invasive epicardial ablation of lone atrial fibrillation in pediatric patient. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2010;90:e49–e51. 129. Vermond RA, Geelhoed B, Verweij N, et al. Incidence of atrial fibrillation and relationship with cardiovascular events, heart failure, and mortality: A community-based study from the Netherlands. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015;66:1000–7 130. Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998;98:946–52** In subjects from the original cohort of the Framingham Heart Study, AF was associated with a 1.5- to 1.9-fold mortality risk even after adjustment for the pre-existing cardiovascular conditions. 131. Lakshminarayan K, Solid CA, Collins AJ, Anderson DC, Herzog CA. Atrial fibrillation and 28 Ac ce pt ed M an us cr ip t stroke in the general medicare population: a 10-year perspective (1992 to 2002). Stroke 2006;37:1969–74 132. Maaijwee NAMM, Rutten-Jacobs LCA, Schaapsmeerders P, van Dijk EJ, de Leeuw F-E. Ischaemic stroke in young adults: risk factors and long-term consequences. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:315–25 133. Kleemann T, Becker T, Strauss M, Schneider S, Seidl K. Prevalence of left atrial thrombus and dense spontaneous echo contrast in patients with short-term atrial fibrillation < 48 hours undergoing cardioversion: Value of transesophageal echocardiography to guide cardioversion. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 2009;22:1403–8 134. Airaksinen KEJ, Grönberg T, Nuotio I, et al. Thromboembolic complications after cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: The FinCV (Finnish CardioVersion) Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2013;62:1187–92 135. Nuotio I, Hartikainen JEK, Grönberg T, Biancari F, Airaksinen KEJ. Time to cardioversion for acute atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic complications. JAMA 2014;312:647–9 136. Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factorbased approach: the Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 2010;137:263–272.** The study describes the CHA2DS2-VASc risk scheme. 137. Macle L, Cairns J, Leblanc K, et al. 2016 Focused Update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:1170–85 138. Khairy P, Aboulhosn J, Broberg CS, et al. Thromboprophylaxis for atrial arrhythmias in congenital heart disease: A multicenter study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016;223:729–735. 139. Gaita F, Corsinovi L, Anselmino M, et al. Prevalence of silent cerebral ischemia in paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation and correlation with cognitive function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:1990–7 * This study shows a positive association between AF, silent cerebral ischemia and cognitive dysfunction in young patients with AF. 140. Horner JM, Horner MM, Ackerman MJ. The diagnostic utility of recovery phase QTc during treadmill exercise stress testing in the evaluation of long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2011;8:1698–04 141. Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 1994;271:840–4 142. Heeringa J, Kors JA, Hofman A, van Rooij FJA, Witteman JCM. Cigarette smoking and risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam Study. Am. Heart J. 2008;156:1163–9 143. Chaker L, Heeringa J, Dehghan A, et al. Normal Thyroid Function and the risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100:3718–24 144. Mitchell GF, Vasan RS, Keyes MJ, et al. Pulse pressure and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA 2007;297:709–15 145. Marcus GM, Alonso A, Peralta CA, et al. European ancestry as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in African Americans. Circulation 2010;122:2009–15 146. Oyen N, Ranthe MF, Carstensen L, et al. Familial aggregation of lone atrial fibrillation in young persons. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;60:917–21 29 Table 1 Initial specific evaluation in young adults presenting with AF Evaluation: To identify: • • • ECG • TTE ip t To rule out cardiomyopathy Left atrial size Pre-excitation syndrome LQT: QTc during recovery phase ≥ 460 ms ed Exercise testing • • • • • Reeentrant tachycardia Electrophysiological study Blood test • To identify a predisposing arrhythmia such as AVNRT or AVRT Thyroid, renal and hepatic function ce pt Holter monitoring • (29, 34) cr Family history us • • • (11-16, 25) (43, 55-57) an • Symptoms Precipitating factors: alcohol use, drugs Predisposing factors resumed in Table 2 (obesity, exercise ..) Familial atrial fibrillation Genetic disease Familial history of syncope, drowning, sudden cardiac death Pre-excitation syndrome Long QT, Short QT Repolarization anomalies (anterior repolarization syndrome, Brugada syndrome or others) Response to antiarrhythmic therapy M History and physical exam • • References (140) (101) (101) Ac TTE for transthoracic echography, AVNRT for atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia and AVRT for atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia. 30 Table 2 Known predisposing factors for AF 2.1 2.2 Hypertension 1.5 1.4 Diabetes mellitus 1.4 1.6 1.07 Obstructive sleep apnea 3.29 1.1 Exercise 3.1 1.6 ed Alcohol use 1.4 M Smoking an Obesity (per kg/m2) 1.6 1.2 ce pt Hyperthyroidism Increased pulse pressure Myocardial infarction 1.4 1.2 Valvular heart disease 1.8 3.4 Heart failure 4.5 5.9 European ancestry Family history Ac Ventricular diastolic dysfunction, left atrial dilatation Ventricular diastolic dysfunction, left atrial dilatation Atrial and cellular remodelling Left atrial dilatation, hypertension Hypoxemia, hypertension, ventricular diastolic dysfunction Left atrial and cellular remodelling Left atrial dilatation, increasing vagal tone Ventricular diastolic dysfunction, vagal tone Cellular remodelling Atrial remodelling Ventricular diastolic dysfunction, atrial remodelling Atrial remodelling Atrial remodelling and overload Genetic variant Genetic variant us Increasing age (per 10 years) Supposed mechanisms 1.13 1.4 References (141) ip t Relative risk men women (141) cr Clinical Risk Factors (141) (11) (11) (142) (23) (25) (143) (144) (141) (141) (141) (145) (29, 146) 31 Figure legends: Figure 1: ECG of patient affected with BrS and AF (25 mm/s; 10 mm/mV) Figure 2: Polymorphic atrial tachyarrhythmia associated with LQTS. ip t ECG (25 mm/s; 10 mm/mV) was recorded in a 21-year-old man previously diagnosed with LQT1 after syncope. Note the particular aspect of AF which appears quite organised. It is permission (67). us cr also known as a polymorphic atrial tachyarrhythmia. Modified from Kirchof et al. with Figure 3: ECG of a 17-year-old man presenting both paroxysmal AF and SQTS. an Modified from Villafane et al. with permission (73) (25 mm/s; 10 mm/mV) M Figure 4: ECG of a 19-year-old man presenting with LMNA mutation. He presented with AF at 11 years of age and suffered aborted sudden cardiac death at the ed age of 19 years. Conduction disturbance associated with AF led to detection of mutations in ce pt SCN5A and LMNA genes. (25 mm/s; 10 mm/mV) Figure 5: ECG of a patient presenting with WPW syndrome and AF Ac (25 mm/s; 10 mm/mV) 32 ip t cr Ac ce pt ed M an us Figure 1 Figure 2 33 ed ce pt Ac ip t cr us an M Figure 3 34 ed ce pt Ac Figure 4 35 ip t cr us an M ed ce pt Ac ip t cr us an M Figure 5 36