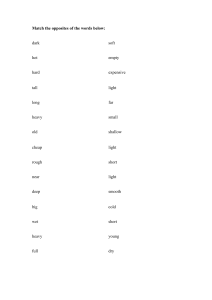

Paradigmatic sense relations • Semasiology • Onomasiology There are various types of sense relations. Traditionally, semantics looks at synonymy, homonymy, polysemy, hyponymy, meronymy and oppositeness of meaning which includes the misleading familiar concept of antonyms. Homonymy • Homonymy is the situation in which one word-form has two or more very different meanings, felt to be unrelated for example, the bank of a river, and the bank that gives or denies you overdraft facilities. Bank (1) and bank (2) are absolute homonyms. There are special cases of partial homonymy – sometimes the words sound the same but look different: for example, the waist that you attach your belt around versus the waste that you throw in the dustbin. These are homophones. Alternatively, words may look identical but sound different – thus you might weep a single tear if you tear your best jacket. These are homographs. • A special case of homonymy has been identified as grammatical homonymy or polyfunctionality. This term describes cases in which one morphosyntactic word is associated with two distinct lexemes and with a set of distinct grammatical meanings: e.g. plays – i) verb, 3rd p. sg. pres. t. and ii) noun, common, countable, pl. Polysemy • One form = many senses Skirt, school, sister. Condition on polysemy – the numerous meaning have to be related in the cognitive unconscious of native speakers, i.e. we should be able analytically to define the process of meaning derivation which have lead to the development of the separate senses. Meaning extension (broadening) and the reverse specialisation (narrowing) are thw two most frequent processes resulting in new related senses. Synonymy • What does it mean to say that words have the same or similar meaning? If you want to look up the synonyms a word has, then you go to a Thesaurus, a reference book sometimes known as a reverse-dictionary because it is classified by meanings, not alphabetically, by word-forms. Hyponymy • One of the most important structuring relations in the vocabulary of a language is hyponymy. This is the relation between apple and fruit, car and vehicle, slap and hit, and so on. We say that apple is a hyponym of fruit, and conversely, that fruit is a superordinate (occasionally hyperonym) of apple. This relation is often portrayed as one of inclusion. However, what includes what depends on whether we look at meanings extensionally or intensionally. From the extensional point of view, the class denoted by the superordinate term includes the class denoted by the hyponym as a subclass; thus, the class of fruit includes the class of apples as one of its subclasses. • Each hyponym has at least one additional feature or property which makes it a specific subclass of the general class but also inherits all the features of its superordinate. For this reason hyponymy is defined as a transitive ISA relationship of inheritance. It is a transitive relation. Hyponymy is often defined in terms of entailment between sentences which differ only in respect of the lexical items being tested: It's an apple entails but is not entailed by It's a fruit, Mary slapped John entails but is not entailed by Mary hit John. Meronymy • Another relation of inclusion is meronymy, which is the lexical reflex of the more general cognitive category of the part-whole relation. Examples of meronymy are: hand:finger, teapot:spout, wheel:spoke, car:engine, telescope:lens, tree:branch, and so on. In the case of finger:hand, finger is said to be the meronym (the term partonym is also sometimes found) and hand the holonym. Meronymy shows interesting parallels with hyponymy. (They must not, of course, be confused: a dog is not a part of an animal, and a finger is not a kind of hand.) • In both cases there is inclusion in different directions according to whether one takes an extensional or an intensional view. A hand physically includes the fingers (notice that we are not dealing with classes here, but individuals); but the meaning of finger somehow incorporates the sense of hand, (Langacker says that the concept "finger" is 'profiled' against the domain "hand".) Oppositeness of meaning • • • Everyone, even quite young children, can answer questions like What's the opposite of big/long/heavy/up/out/etc.? Oppositeness is perhaps the only sense relation to receive direct lexical recognition in everyday language. It is presumably, therefore, in some way cognitively primitive. However, it is quite hard to pin down exactly what oppositeness consists of. Complementaries Antonyms Directionals – Reversives (Reverses) – Converses Complementaries • The following pairs represent typical complementaries: dead:alive, true:false, obey: disobey, inside:outside, continue (V.ing):stop (V.ing),possible:impossible, stationary: moving, male:female. Complementaries constitute a very basic form of oppositeness and display inherent binarity in perhaps its purest form. Some definite conceptual area is partitioned by the terms of the opposition into two mutually exclusive compartments, with no possibility of 'sitting on the fence'. Hence, if anything (within the appropriate area) falls into one of the compartments, it cannot fall into the other, and if something does not fall into one of the compartments, it must fall into the other (this last criterion distinguishes complementaries from mere incompatibles). Antonymy • The most extensively studied opposites are undoubtedly antonyms. (Note that antonymy is frequently used as a synonym for oppositeness; but its terminological meaning includes only gradable opposites of the good/bad type.) kind:cruel clever:dull pretty:plain polite:rude long:short fast:slow wide:narrow heavy:light strong:weak large:small thick:thin high:low deep:shallow Exception: • Normal language behavior: ungradable concepts can sometimes be graded in speech. The reasons for this are pragmatic. Example • John is more of a bachelor than Daniel (i.e. more determined never to get married, partying, had never had a stable girlfriend, etc.) • I am more alive now than ever (i.e. feeling more energetic, satisfied with my life, etc). Reversives • Reversives belong to a broader category of directional opposites which include straightforward directions such as up:down, forwards:backwards, into:out of, north: south, and so on, and extremes along some axis, top:bottom (called antipodals in Cruse (1986)). Reversives have the peculiarity of denoting movement (or more generally, change) in opposite directions, between two terminal states. They are all verbs. The most elementary exemplars denote literal movement, or relative movement, in opposite directions: rise:fall, advance:retreat, enter:leave. • The reversivity of more abstract examples resides in a change (transitive or intransitive) in opposite directions between two states: tie:untie, dress:undress, roll:unroll, mount:dismount. Converses • Converses are often considered to be a subtype of directional opposites. • • • They are also, paradoxically, sometimes considered to be a type of synonym. There are valid reasons for both views. Take the pair above:below, and three objects oriented as follows: A B C We can express the relation between A and B in two ways: we can say either A is above B, or B is below A. The logical equivalence between these two expressions is what defines above and below as converses. But since both are capable of describing the same arrangement, a unique situation among opposites, there is some point in thinking of them as synonyms conditioned by the order of their arguments. Consider now, however, A and C in relation to B: clearly A is above B and C is below B, hence above and below denote orientations in opposite directions, and are therefore directional opposites. • Other converse pairs with a salient directional character are: bequeath:inherit, buy:sell (a double movement, here, of money and merchandise). The directional nature of some converse pairs, however, is pretty hard to discern (husband:wife, parent:offspring, predator:prey), although it is perhaps not completely absent. Converses may be described as two-place if the relational predicate they denote has two arguments (e.g. above:below) and three-place if it has three (e.g. lend: borrow: A borrowed B from C or C lent B to A); buy:sell are arguable fourplace converses: John sold the car to Bill for £5,000/Bill bought the car from John for £5,000. This is just the tip of the iceberg. Delving into the depths of language takes a lifetime. References • Cruse, A. (2011) Meaning in Language: An Introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics. OUP • Fromkin, V., Rodman, R. and Hyams, N. (2010/2007) An Introduction to Language. Thomson/Heinle, Boston, Mass • Hurford, J., Heasley, B. and M. Smith (2007) Semantics: A Coursebook. CUP • Leech, G. (1997) Semantics. Penguin.