Grace Ogot, - Land Without Thunder Short stories (1996, East African Educational Publishers) - libgen.li

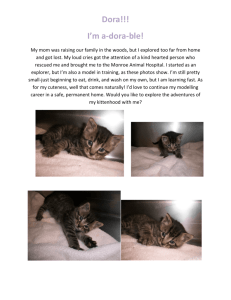

advertisement