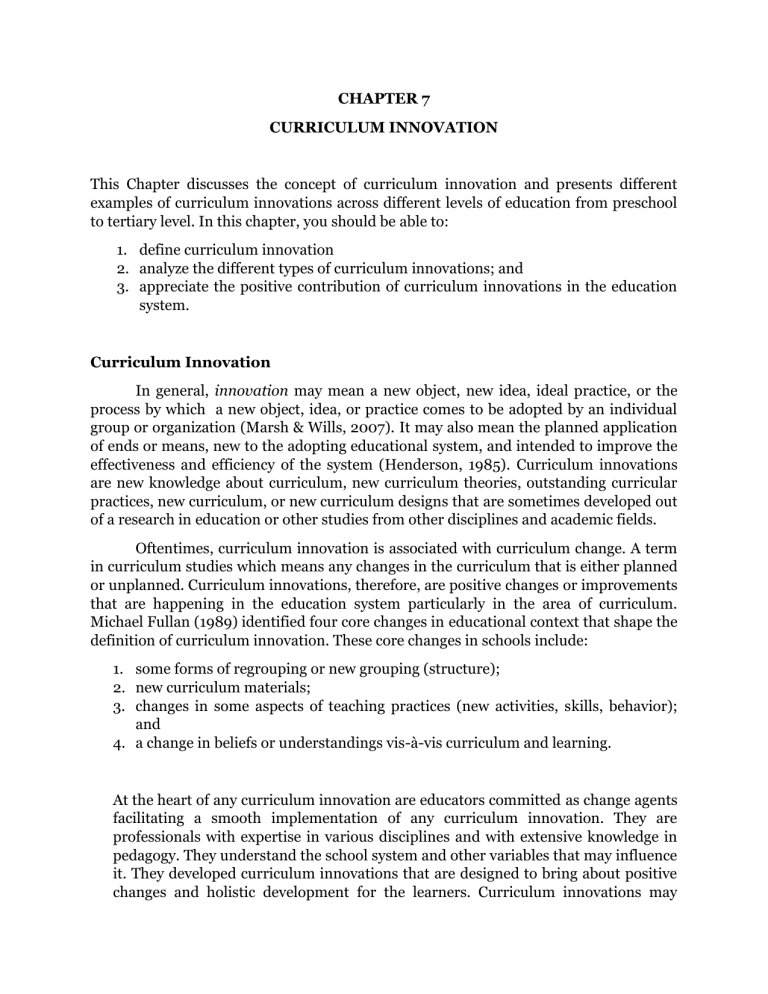

CHAPTER 7 CURRICULUM INNOVATION This Chapter discusses the concept of curriculum innovation and presents different examples of curriculum innovations across different levels of education from preschool to tertiary level. In this chapter, you should be able to: 1. define curriculum innovation 2. analyze the different types of curriculum innovations; and 3. appreciate the positive contribution of curriculum innovations in the education system. Curriculum Innovation In general, innovation may mean a new object, new idea, ideal practice, or the process by which a new object, idea, or practice comes to be adopted by an individual group or organization (Marsh & Wills, 2007). It may also mean the planned application of ends or means, new to the adopting educational system, and intended to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the system (Henderson, 1985). Curriculum innovations are new knowledge about curriculum, new curriculum theories, outstanding curricular practices, new curriculum, or new curriculum designs that are sometimes developed out of a research in education or other studies from other disciplines and academic fields. Oftentimes, curriculum innovation is associated with curriculum change. A term in curriculum studies which means any changes in the curriculum that is either planned or unplanned. Curriculum innovations, therefore, are positive changes or improvements that are happening in the education system particularly in the area of curriculum. Michael Fullan (1989) identified four core changes in educational context that shape the definition of curriculum innovation. These core changes in schools include: 1. some forms of regrouping or new grouping (structure); 2. new curriculum materials; 3. changes in some aspects of teaching practices (new activities, skills, behavior); and 4. a change in beliefs or understandings vis-à-vis curriculum and learning. At the heart of any curriculum innovation are educators committed as change agents facilitating a smooth implementation of any curriculum innovation. They are professionals with expertise in various disciplines and with extensive knowledge in pedagogy. They understand the school system and other variables that may influence it. They developed curriculum innovations that are designed to bring about positive changes and holistic development for the learners. Curriculum innovations may focus on the classroom or school level, or they could be changes specific to a particular discipline. In this book, curriculum innovations are clustered into several ideas that continue to shape curriculum and education systems in general. A. Standards-based Curriculum A standards-based curriculum is designed based on content standards as explicated by experts in the field (Glatthorn et al., 1998). Curriculum standards include general statements of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that students should learn and master as a result of schooling (Marzano, 1996; Glatthorn et al., 1998). They are statements of what students should know and be able to do. Standards generally include three different aspects: knowledge, skills, and dispositions. 1. Knowledge or Content Standards describe what students should know. These include themes or conceptual strands that should be nurtured throughout the students’ education. 2. Skills Standards include thinking and process skills and strategies that students should acquire. 3. Dispositions are attitudes and values that should be developed and nurtured in students. Curriculum standards are different from competencies. Standards are broader while competencies are more specific and prescriptive in terms of the scope of knowledge, skills, and values that students should learn. Curriculum standards provide more creativity and freedom for educators to explore various learning opportunities and better forms of assessing students’ achievement (Morrison, 2006). Literatures offer many reasons or positive benefits for developing curriculum standards. For instance, curriculum standards provide a structure that allows students to learn common knowledge, skills, and values. They give direction or framework in designing a course. VanTassel-Baska (2008) identified varieties of benefits of using curriculum standards to education: 1. Ensure that students learn what they need to know for high-level functioning in the 21st century. 2. Ensure educational quality across school districts and educational institutions. 3. Provide educators with guideposts to mark the way to providing students with meaningful outcomes to work on. 4. Provide a curriculum template within which teachers and candidates are able to focus on instructional delivery techniques that work. Activity 1. What are the possible benefits of a multicultural curriculum? B. Indigenous Curriculum The idea of an indigenous curriculum was a product of a vision to make curriculum relevant and responsive to the needs and context of indigenous people. It links the curriculum with the society’s culture and history. It values the importance of integrating indigenous knowledge systems of the people to the existing curriculum. The Author’s earlier studies on indigenous curriculum provided a framework for linking indigenous knowledge with the curriculum and provided several dimensions that serve as a framework for the development of an indigenous curriculum: 1. Construct knowledge so that young children understand how experiences, personal views, and other peoples’ ideas influence the development of scientific concepts and scientific knowledge. 2. Use instructional strategies that promote academic success for children of different cultures. 3. Integrate contents and activities that reflect the learners’ culture, history, traditions, and indigenous knowledge in the curriculum. 4. Utilize community’s cultural, material, and human resources in the development and implementation of the curriculum. Specifically, indigenous curriculum may consider using and implementing the following strategies at the school level: 1. Integrating contents and activities that reflect the learners’ culture, history, traditions, and indigenous knowledge in the curriculum. 2. Using the local language as the medium of instruction for several subjects like Math, Science, Social Studies, Physical Education, Music, Values Education, and Home Economics and Livelihood Education. 3. Involving community folks and local teachers in the development of the curriculum. 4. Developing local instructional materials and learning outside the classroom by utilizing various community resources that are available for conducting observations and investigations. 5. Using instructional strategies that are relevant to indigenous learning system. As a form of innovation, an indigenous curriculum is founded on the way of life, traditions, worldview, culture, and spirituality of the people, and it is a pathway of education that recognizes wisdom embedded in indigenous knowledge. This indigenous knowledge is very influential to the development of young children. It is embedded in their daily life since the time they were born. They grow up into a social and cultural setting-family, community, social class, language, and religion. An indigenous curriculum, therefore, is a noble way of responding to the needs of indigenous people. In an indigenous curriculum, the first frame of reference for developing a curriculum must be the community, its environment, its history, and its people (Pawilen, 2006, 2013). Activity 2. Answer the following questions: 1. What indigenous knowledge can be integrated in the curriculum? 2. What are examples of indigenous curriculum implemented in the Philippines? C. Brain-based Education Prominent advocates in brain-based education, Caine and Caine (1997) considered curriculum and instruction from a brain-based approach. They begin with brain-mind learning principles derived from brain research findings and apply these principles in the classroom and in designing a curriculum. These principles are: 1. The brain is a whole system and includes physiology, emotions, imagination, and predisposition. These must all be considered as a whole. 2. The brain develops in relationship to interactions with the environment and with others. 3. A quality of being human is the search for personal meaning. 4. People create meaning through perceiving certain patterns of understanding. 5. Emotions are critical to the patterns people perceive. 6. The brain processes information into both parts and wholes at the same time. 7. Learning includes both focused attention and peripheral input. It is designed to engage the learners to the core of knowledge development in each discipline. Autonomous Learner Model Betts (2004) pointed out that curricular offerings typically fall into three levels. Level I is a prescribed curriculum and instruction that focuses on state standards. Level II involves differentiation of curriculum based on individual differences. Level III features learner-differentiated options where students are self-directed and teachers provided opportunities for the learners to be in charge of their learning. This model focuses on the third level. The Autonomous Learner Model is divided into five major dimensions: a. Orientation acquaints students, teachers, and administrators with the central concept in gifted education and the specifics of this model. At this level, gifted students work together in doing self-understanding exercises that will help them be familiarized with each other. The students are expected to develop an Advance Learning Plan as part of their orientation experience that includes information about their giftedness, various personal and academic needs, learning experiences they might need, and other things that will help them succeed in school. b. Individual Development focuses more clearly on developing skills, concepts, and attitudes that promote lifelong learning and self-directed learning. c. Enrichment Activities involve two kinds of differentiation of curriculum, namely (1) differentiation of curriculum by the teacher and (2) differentiation by the student. Students are exposed to various activities to develop their passion for learning. d. Seminars are designed to give each person in a small group the opportunity to research a topic and present it in seminar format to other people or to a group. e. In-depth Study is one in which students pursue areas of interest in long-term individual or small group studies. The students will decide what will be learned, the process of doing it, the product, how content will be presented, and how the entire learning process will be evaluated. Integrated Curriculum Model This model is a popular way of organizing or designing different kinds of curriculum. The Center for Gifted Education at the College of William and Mary developed its curriculum based on this model and has trained many teachers around the world in using their curriculum materials (Davis et al., 2011). The model presented three dimensions based on the model of VanTassel-Baska (1987) that guide the development of the curriculum. a. Advance Content Dimension meets the needs of gifted students for acceleration by providing content earlier and faster than same-age peers would normally receive it. Content area experts and educators work collaboratively to develop the content, and they align key topics, concepts, and habits of mind within a domain to content area standards. b. Process/Product Dimension incorporates direct instruction and embedded activities that promote higher-order thinking skills and create opportunities for independent pursuit in areas of student interest. c. Issues/Themes Dimension is where learning experiences are organized. In doing so, students are able to develop deeper ideas and philosophies that ultimately promote understanding of the structure of knowledge learned. Kids Academia Model Kids Academia is a program for young Japanese children ages 5-8, which was developed by Dr. Manabu Sumida in 2010. The program is designed to provide excellent science experiences for gifted children in Japan. The kids who participated in the program were rigorously selected using a checklist adopted from the Gifted Behavior Checklist in Science for Primary Children. Faustino, Hiwatig, and Sumida (2011) identified three major phases that are followed in the development of the curriculum. a. Group Meeting and Brainstorming Activities. The teachers and teaching assistants hold several meetings and brainstorming activities to decide on the themes that will be included in the program. A general orientation of the program is also done during in this phase. b. Selection of Contents for Each Theme. The teachers and teaching assistants carefully select the lessons and topics that are included in the theme. A rigorous study of the topic is done in this phase. c. Designing Lessons. This phase includes the careful preparation of lesson plans and other instructional materials needed for implementing each lesson. The activities for each lesson were selected based on the following guidelines developed by Dr. Sumida: a. Stimulates the interest of the children b. Allows children to express their own ideas and findings c. Uses cheap and easy-to-find materials d. Teaches the correct use of scientific terms e. Uses simple laboratory equipment f. Allows individual or group activities g. Encourages socio-emotional development h. Connects to other subjects and to everyday life experiences i. Includes topics related to family and community j. Uses materials connected to family and community k. Applies what children learned to their families and society In addition, the program adapted the Wheel of Scientific Investigation and Reasoning as a guide for developing skills of gifted children. Activity 3. 1. What are the possible pitfalls of implementing a differentiated curriculum? D. Technology Integration in the Curriculum Technology offers multiple opportunities to improve teaching and learning and in the total education system. The internet, for example, provides vast information that people may need to know. The Internet is more than just a collection of knowledge. It also offers different ways and opportunities for discovering and sharing information. Nowadays, everything is almost possible with a single click of the computer mouse and by using search engine. Technology integration is breaking the geographical barriers in education. It is creating a new space for meaningful learning. With technology, it is now possible to connect and interact with other schools, educators, and other institutions from different parts of the world. There are several innovations from basic education to graduate education that are associated or influenced by technology integration. Some of these innovations are: distance education; computer-assisted instruction; online learning; teleconferencing; online libraries; webinars; online journals; and e-books. ICT literacy is now fast-becoming an important form of literacy that is essential for each learner to learn and master. It also requires all teachers to be ICT literate to be able to utilize technology to enhance or improve the way they teach. It is also important for teachers to teach students how to use technology responsibly, especially with the current popularity of social networking and other technological innovations. Activity 4. Answer the following questions: 1. How can ICT integration in education help to address educational issues on quality and access? 2. What are the different curricular and instructional innovations related to ICT integration being implemented in Philippine schools? E. Outcomes-based Education Outcomes-based education (OBE) is one of the dominant curriculum innovations in higher education today. It came out as a curricular requirement for specific fields of study in engineering, nursing, and tourism education, among others. ASEAN education framework for higher education requires all colleges, universities, and institutes to transform all their educational programs to OBE. OBE is defined as a curriculum design that ensures coherent, logical, and systematic alignment between and among the different levels of outcomes. OBE also ensures connection among the essential elements of the curriculum: intent, content, learning experiences, and evaluation. As a curriculum design, it seeks to ensure that the necessary instructional support system, learning environment, and administrative support system are in place based on the desired outcomes developed by a HEI. It supports the quality assurance system. Basically, an educational outcome is a culminating demonstration of learning (Spady, 1993). It includes what the student should be able to do at the end of a course (Davis, 2003). Outcomes are clear learning results that we want students to demonstrate at the end of significant learning experiences and are actions and performances that embody and reflect learner competence in using content, information, ideas, and tools successfully (Spady, 1994). Figure 18 shows the different levels of outcomes in OBE. At the institutional level, this includes the philosophy, vision, mission, and aims of the institution. They are statements of what a HEI hopes to contribute to the society. At the program level, these are the goals, program competencies, and a course outcomes that all students should master and internalize. At the instructional level, outcomes include the learning objectives for every course in higher education. At any level, outcomes should be mission-driven, evidence-based, and learning-focused. Institutional Level Philosophy Vision Mission Aims Program Level Course Level Program Goals Program Competencies Course Objectives Instructional Objectives Figure 18. Different Levels and Types of Outcomes OBE as a curriculum design enables higher education institutions to develop various curricula based on the needs of students and the demands of society. It encourages educational institutions to clearly focus and organize the learning environment that supports the development of students and the implementation of the curriculum. This means starting with a clear picture of what is important for students to be able to do, then organizing the curriculum, instruction, and assessment to make sure this learning ultimately happens. OBE is an approach to planning, delivering, and evaluating instruction that requires administrators, teachers, and students to focus their attention and efforts on the desired results of education (Spady, 1994). Hence, it is a process that involves the restructuring of curriculum, assessment, and reporting practices in education to reflect the achievement of high-order learning and mastery rather than accumulation of course credit. It is important that when designing a curriculum for OBE, the competencies and standards should be clearly articulated. Writing the learning outcomes in OBE closely resembles Robert Mager’s guidelines (1984) that include expected performance, the conditions under which it is attained, and the standards for assessing quality. According to Spady (1994), there are two common approaches to an OBE curriculum, namely: 1. Traditional/Transitional Approach emphasizes student mastery of traditional subject-related academic outcomes (usually with a strong focus on subject- specific content) and cross-discipline outcomes (such as the ability to solve problems or to work cooperatively). 2. Transformational Approach emphasizes long-term cross-curricular outcomes that are related directly to students’ future life roles (such as being a productive worker or a responsible citizen or a parent). Spady (1994) also identified four essential principles of OBE. These are as follows: 1. Clarity of Focus means that everything teachers do must be clearly focused on what they want learners to ultimately be able to do successfully. 2. Designing back means that the starting point for all curriculum design must be a clear definition of the significant learning that students are to achieve by the end of their formal education. 3. High expectations for all students. 4. Expanded opportunities for all learners. Designing curriculum based on OBE principles is a noble process of making curriculum relevant and responsive to the students’ needs and requires a paradigm shift in teaching and learning. Malan (2000) identified several features of outcomes-based learning. It is needs-driven. Curricula are designed in terms of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes expected from graduates and aim to equip students for lifelong learning. It is outcomes-driven. The model has a line that runs from taking cognizance of training needs to setting an aim (purpose) for the program, goals for syllabus themes, learning outcomes, and finally assessing the learning outcomes in terms of the set learning objectives. It has a design-down approach. Linked to the needs and the purpose of the program, learning content is only selected after the desired outcomes have been specified. Content becomes a vehicle to achieve the desired learning outcomes, which are aimed at inculcating a basis for lifelong learning. It specifies outcomes and levels of outcomes. Learning objectives are described in terms of Benjamin Bloom’s cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains and set according to Robert Mager’s guidelines for formulating objectives. The focus shifts from teaching to learning. The model has a student-centered learning approach where lecturers act as facilitator. Study guides help the learners to organize their learning activities and group work, continuous assessment, and self-assessment are major features. The framework is holistic in its outcomes’ focus. Although the learning objectives are aimed at learning at grassroots level, they are linked to goals and aims at higher levels. Attaining learning objectives is, therefore, not an end in itself; it provides building blocks for achieving higher-level outcomes. As a curriculum innovation, OBE is a complete paradigm shift in higher education. It calls for an education that is more focused and purposive. An OBE curriculum is mission-driven that requires all institutions to anchor all their curricular offerings to the curriculum and to the vision, mission, and philosophy of the institution. Outcomes-based Education follows a logical and systematic process that is linear, starting with the institution outcomes. The interrelated processes and the expected outputs are clearly stated. Figure 19 shows the entire process for designing outcomes-based education for any college or university. There are three major phases involved in planning for OBE at the program level. Phase 1 Vision and Mission Charter (For state University and College) Needs and Demands of the society Course Learning Outcomes Program Outcomes Institutional outcomes Goals Competencies Objectives Content Learning Experiences Evaluation Figure 19. OBE Planning Process at Program Level Phase 1. Developing Institutional Outcomes – the first phase of OBE is conducting needs analysis to analyze the vision and mission of the HEI, analyze the charter of the HEI if it is a state college or university, and examine the needs and demands of the society. The result of the needs analysis will serve as the basis for developing the institutional outcomes. The institutional outcome clearly defines the ideal type of graduate that the HEI aims to develop to contribute to the society. The institutional outcome defines the identity of the HEI, which enables them to design the different academic programs and develop the institutional culture that includes the core values of the HEI. Phase 2. Developing Program Outcomes – the second phase of OBE is to design the program. At this level, it is important to identify the desired attributes, knowledge, skills, and values that an ideal graduate of the HEI aims to develop. Development of program outcomes is assigned to different colleges or academic units. The program outcomes reflect the necessary competencies that an ideal graduate of the academic program should possess. It is important that the program outcomes directly reflect the institutional outcome of HEI. Phase 3. Developing Course Learning Outcomes – the third phase is to develop the learning outcomes for different courses. It is important that these learning outcomes reflect the program outcomes set by the college for a particular degree program from undergraduate to graduate and postgraduate levels. Examples of these include BS Biology, BS Mathematics, BS Nursing, BS HRM, Bachelor in Elementary Education (BEED), MD, MA, MS, PhD, and other academic programs offered in the university or college. There are three steps that should be followed in developing learning outcomes: For example, as shown in Figure 20, if the institutional outcomes is to develop responsible leaders, the program outcome specific for the College of Science is to develop responsible leaders who are scientists that are critical thinkers, nationalists, innovators, and effective communicators, among others. The next step for developing program outcomes is for the college involved to develop program outcomes. These program outcomes are statements of the knowledge, skills, values, and professional attitudes that the college wishes to produce for all its graduates. Harden, Crossby, and Davis (1999) also suggested three categories of outcomes that are essential for OBE: tasks, attitudes, and professionalism. Step 1. Step 2 (Ideal Graduate) (Graduate Attributes) Step 3 (Identify Program Outcomes) Example: Critical Thinkers and Creatives Nationalists Scientist Innovators Effective Communicators Program Outcomes Develop critical thinking skills and creativity Produce scientific research on Philippine issues and problems Communicate research findings in various forms to the academe and to the public Figure 20. Process for Developing Program Outcomes Step 1. Developing Course Competencies. Each set of competencies should reflect the nature of the courses, embody the course description, and focus on the learner and learning. Costa and Kallick (2009) encouraged educators to include habits of mind in the course outcomes or competencies. These habits of mind are essential for students to accomplish the desired learning tasks or outcomes. These are behaviors such as striving for accuracy, metacognition, persistence, creating, innovating, taking responsible risks, remaining open to continuous learning, and applying past knowledge to new situations, among others. Step 2. Developing a Curriculum Map. In this process, it is important for the college faculty to develop a curriculum map (see Figure 21) to plot the program outcomes with the specific courses for a particular degree program. In the curriculum map, the contribution made by each course to achieve the expected learning outcomes should be clear. It is necessary to see that each set of course competencies be logically organized in a spiral progression considering two architectonics of curriculum: the vertical organization (sequence) and horizontal organization (scope and integration). Program Outcomes Course 1 Course 2 Courses Course 3 Course 4 Course 5 Program Outcome Competencies Competencies Competencies Competencies Competencies Program Outcome Competencies Competencies Competencies Competencies Competencies Program Outcome Competencies Competencies Competencies Competencies Competencies Figure 21. Sample Curriculum Map Template Step 3. Developing the syllabus. In this process, the faculty will develop the syllabus for each course. This includes identifying course content, learning activities, and course requirements or assessment tools. OBE requires all teachers to focus on the outcomes prescribed for each course. Contrary to many information and lectures that there is a prescribed syllabus template, OBE does not prescribed any template of syllabus. It simply directs teachers that the teaching and learning experiences as reflected in the syllabus should be aligned perfectly with the course competencies. Every faculty member in HEIs is required to prepare syllabus for the courses they will teach. Figure 22 shows a sample of syllabus template that can be used for a class. In OBE, it is important to ensure perfect alignment between and among the four elements of instruction: objectives, contents, learning experiences, and assessment tools. It is also imperative that all these elements contribute to the realization of the program outcomes and institutional outcomes. Course Title Course Description Course Credit Unit Course Schedule Course Objectives Schedule Objectives Contents Learning Experiences References Class Requirements Evaluation Criteria Figure 22. Sample Syllabus Template Assessment Tools In this step, it is imperative that the objectives are in behavioral terms. They should be specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time bound. Objectives should contribute to the realization of the course competencies for a particular course. They should also contribute to the attainment of the program outcomes. The content is based on the course competencies. Contents could be concepts, themes, topics, issues, procedures, processes, projects, or problems that students will learn in relation to the course. The learning experiences should be learner-centered and learning focus. The teacher should use constructivist teaching approaches that will help the students attain the desired course outcomes and contribute to the development of life-long learning skills. It is also desirable to focus on activities that develop 21 st century skills, such as communication skills, collaboration, critical thinking skills, and creativity and innovation skills. In OBE, it is also highly desirable that the assessment tools are best tools that will truly measure students’ performance. It should be constructively aligned to the achievement of the expected learning outcomes. Criterion-referenced assessment is encouraged in OBE; therefore, a clear description of the assessment tool, methods of assessment, and rubrics are included. The references should be updated and useful for understanding the course. The class requirements and the evaluation criteria should be clear and based on the competencies of the course. If a HEI prescribes standard evaluation criteria, then it should be reflected in the syllabus. Activity 5. Answer the following questions: 1. What are the possible benefits of implementing an outcomes-based curriculum in higher education? 2. How does OBE support academic freedom? F. Transition Curriculum The transition program is designed for special learners that are intellectually disabled and those that are physically handicapped. It is designed to meet their special needs and respond to their specific interests. It is like a care package that will empower the learners in their transition from home to school, or from post-elementary or postsecondary to the world of work. In the transition program, the learners will also enjoy an education that will enable them to become functional in their everyday lives. In the Philippines, Quijano (2007) presented the Philippine Model of Transition that focuses on enabling every special learner for community involvement and employment. The model envisions full participation, empowerment, and productivity of those enrolled in the program. The transition program includes three curriculum domains: (1) daily living skills, (2) personal and social skills, and (3) occupational guidance and preparation. This model necessitates the need for support from professionals and other key people in the community in order for the individual with special needs to attain independent living. According to Gomez (2010), this model of transition program can also be used for children in conflict with the law (CICL). The transition Program in the Philippines could be expanded to many different possible of entry that will extend the scope of transition program from young children to adults. These may include the following examples: 1. Transition to school life - may include children and adult special learners who would like to attend or who have been assessed to be ready for regular school under the inclusion program. This may also include students who would like to learn basic literacy programs under the alternative Learning System. 2. Transition after post-secondary schooling – includes programs that will prepare special learners for vocational courses and on-the-job trainings. It may also include programs that will help students move to higher education if possible. 3. Transition from school to entrepreneurship – includes programs that will allow special learners to become entrepreneurs in their respective communities. 4. Transition from school to adult life – includes programs that will allow students to adjust and adapt to adult life. 5. Transition to functional life – includes learning of life skills that will allow the special learners to learn how to take care of themselves and develop some special skills that they can use every day. These entry points for students are important for planning an effective and efficient transition program that is truly relevant and responsive to the needs, interests, abilities, and aspirations of special learners. Transition at any point is an important program to empower special learners to experience normal lives. The transition program aims to realize the aim of the K to 12 basic education program of producing holistically developed and functionally literate Filipino learners in the context of special education. This qualifies it as an organic part of the K to 12 curriculum by providing both academic and extra-curricular support systems to all special learners.