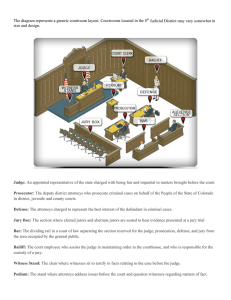

Trial Practice Law: Learning Experience Overview This week's Learning Objectives: Understand the parts and structure of a trial. Recall differences between civil and criminal trials. Review how to manage stress during a trial. Share your learning goals with the class. In this section, we're going to be looking at the trial process. And in this section, we will be talking about the different parts of a trial, the role of evidence, substantive law, and procedural law. So it is important, before you go to court, to know the local rules with regard to trial practice. Every jurisdiction is usually the same. They usually follow the same procedure. But it is important to know whether your local courtroom has any special requirements. The first thing I can advise you to do is to know where to sit in the courtroom. As you know, the plaintiff and the defendant sit in different places. So it's important for you to know where you're going to sit on the first day. You'll have a lot going on, so make sure that you're aware of that. That's one less thing to worry about. Also know who the parties are in the courtroom. Specifically what you want to know is who the clerk is, the clerk is kind of like a judge's assistant, the bailiff, where the bailiff is. Some judges have different requirements for who sits where. So find that out before the trial date. And the best way to do that is to just visit the courtroom before your trial date, observe how things are done, where people sit, who people are, what their duties are. And that will ease your way into the trial. Know the role of the bailiff and where the witness stand is. So the witness stand is typically next to the judge. But some courtrooms have stands that you're not sure if it's the clerk stand or the witness stand. So that is something that you want to find out beforehand, because you're going to have to guide your witness on where to sit during trial. So find that out before trial. Also know the role of the bailiff. The bailiff in some jurisdictions is there for security. In other jurisdictions, they're there to monitor the jury or to help the jury. When I say monitor, just to get basically anything that the jury needs. So find out what that role is. Be prepared. Because it may differ in different jurisdictions. Visit the court beforehand. Like I said, it's really important to visit beforehand. And if you can-even just to find out just where people sit, where you're going to sit. But ideally, if you can bring your witness in, you can maybe do a practice run with your witness testimony, that way they feel comfortable when they actually come to trial, they know where to sit, they know what to expect. Most judges, if you ask them, will allow you to do that. But make sure you ask them first. You also want to observe the judge. Every judge has a different way of looking at things, a different way of doing things. Some judges don't want you to stand in their courtroom, others do. Some judges want you to sit in certain places. Some judges won't allow you to talk. Others want you to whisper. Some expect you to go outside. So all of those things will be important for you. So make sure you find out about it before. You also want to ask the judge's clerk for a map of the courtroom. In a jury trial, most courtrooms have a map of where they're going to sit the potential jurors. And so you want to get that map beforehand, because that is how you're going to organize your jury panel. And you should be able to identify them by name. So it's important that you know where each juror is going to sit before the trial. Ask the clerk when the jury questionnaires will be available for review. Some jurisdictions are available a month before. Some jurisdictions are available 10 minutes before the trial. So that is something that you want to find out beforehand. You don't want to wait till the last minute, if you can avoid it. Because ideally, you're going to go through that jury questionnaire and you're going to find out which jurors that you think you can use a strike on, a juror that you'd like to use a peremptory challenge on. And we'll discuss those later in the term. But those are all important. The only way you're really going to know that is by looking at the jury questionnaires and see how they answer questions. And then ask other attorneys. Your best resource is to ask other attorneys. Is there something that this judge doesn't like? Is there something that I should know about the way the judge does a jury trial? It's not unusual for different courtrooms within the same jurisdiction to do jury selection differently. So you want to ask the clerk, you want to ask other attorneys, to make sure that you're doing it correctly before trial. So typically, your trial is going to take place, it depends on the type of the case, but usually anywhere from six to 12 months from the date of the bond arraignment. The bond arraignment is usually the first day of the court setting, the very first court setting. So it's usually six to 12 months. Nowadays with the pandemic, we're really behind in most jurisdictions. I've had cases that were up to four years before I went to trial. Of course, you're dealing with issues with speedy trial and things like that. But with the pandemic, you should expect quite a few cases to be backed up. So it's important to know, if you do have a trial set, what your judge's position on taking a plea is or settling the case. Some judges will only allow you to plead what we call straight up to the charges if you wait till the last minute. Find that out beforehand. Don't wait to take a plea on the day of trial, because some judges may not accept it. So jury selection is also known as voir dire. And what voir dire means is "to tell the truth." Ultimately, what we're looking for is jurors that can be fair and impartial. That's the ultimate question. Usually with new attorneys, what they do is they ask these really interesting questions about new jurors backgrounds and things like that. But ultimately, they forget to ask the ultimate question, can you still be fair and impartial in this case? Because ultimately, that's what we're looking for. In order to make sure that you're choosing the right jury for your case, you want to get the jury questionnaires beforehand. You want to review the jury questionnaires before you get in the court. And when you look at these jury questionnaires, ultimately again, what you're looking for is whether the juror can be fair and impartial. You look at the jury questionnaires and develop questions based on their answers in the jury questionnaire to see if they can possibly be fair and impartial. Also you want to take a look at the size of a jury. Different jurisdictions have different numbers of jurors that will be assigned or will be seated for a case. So find out how many that is. Some jurisdictions, it's six. Other jurisdictions, it's 12. Some judges actually, or always in a case, may assign alternate jurors, too. And that can be discretionary, how many they have. So find out beforehand how many jurors are going to be seated. Prepare the jury panel seating chart before jury selection. So after you get the jury questionnaires, you reviewed all of them, then you're going to set up a jury seating chart. Ideally, in voir dire, you are calling jurors by their entire name or at least their last name. The worst thing you can do, and again, check your local jurisdiction, is to just call them a number. Really, if there's a-- juries often decide who they want to side with in voir dire. So if you're in a situation where you're calling people by number and opposing counsel is using your name, usually they're going to like the opposing counsel better. That's, I think, human nature. So you want to have the jury seating chart, if you can, created before voir dire starts. So peremptory challenges and strike for cause-- so the way that you get rid of jurors that you do not want in your jury panel or your ultimate jury is either for cause or peremptory challenge. For cause says that a juror cannot be fair and impartial. So ultimately, what you're looking for in jury selection and when you review the jury questionnaires is whether or not a person can be fair and impartial. So for example, if you are maybe a defense attorney in a criminal case and somebody says that they believe what officers say 100% of the time and simply because the defendant is sitting at the defense table, he must have done something wrong, that's an example of somebody that may not be able to be fair and impartial. So that would be an example of a strike for cause. But again, they may say that all day, but if you don't ask, would that affect your ability to be fair and impartial in this case, it's not going to be enough. You need to basically have the juror admit that they cannot be fair and impartial in order to use a strike for cause. Peremptory is a little bit different. You can use a peremptory, and again, this is based on your local jurisdiction, for any reason except race, gender, and sometimes socioeconomic status. You want to check your case law, you want to check your court rules, to see what those factors are. But generally, you can use a peremptory for any other reason besides those. Another issue that comes up is a Batson challenge. A Batson challenge says that somebody used a strike, a peremptory strike, of a potential juror just because of the person's race. So what happens in those cases is the striking attorney needs to have a reason using a peremptory strike other than race, gender, or socioeconomic status. So preliminary instructions of law-- so what's going to happen is the judge is going to, initially when the jury is seated, he or she is going to go over the instructions for the case. And it basically summarizes the jury's duties in the case. The most important thing that I can tell you is you do not speak with jurors outside of the presence of the judge and opposing counsel. What that means in English is don't talk to them outside the courtroom. Do not do it. Your judge will usually give an instruction notifying the jurors that if you see the attorney in the elevator or something like that, they're not being rude, they just can't speak with you. That is absolutely true. If you do speak with a juror, even just pleasantries like how's your day or things like that, that could result in a mistrial. And a mistrial means that you have to do the entire case over from scratch with a new jury. So you want to avoid that at all costs. So avoid any interaction with jurors. And that way, you can avoid allegations of jury tampering, which could affect your bar license as well. So it's critical that you do not speak with jurors outside the courtroom. Another thing that you're going to see preliminary before a trial starts is one of the parties invoking the rule. You're going to find in law that we often come up with one word for many different things. But at the very beginning of a trial, invoking the rule, you're going to hear the rule a lot, but invoking the rule at the beginning of trial is saying that you are asking all witnesses who will be testifying in the case to leave the courtroom. And the reason we do that is so that the witnesses don't hear each other's testimony. It's very important to keep everybody's testimony separate. So that's the reason why we invoke the rule. So the next step in the trial is opening statements. An opening statement provides an outline of the case for the jury. So it pretty much outlines the witnesses and the expected testimony from each of the witnesses. You're only discussing the facts in this case, not arguments. There should be no legal argument in opening statements. And if you do argue the law, you will actually probably draw an objection from the opposing party. Opening statements can be waived. Again, look at your local jurisdiction. But it's not recommended, unless it's a bench trial. And there's some back and forth on whether or not you should do that, too. But generally for a jury trial, do not waive opening statements. What the opening statements do is they give the jury an understanding of what they're going to be listening for during the trial. It can be based on a chronological and/or based on a theme. Depending on the case, sometimes chronological works, basically saying what happened from the beginning of the case to the end of the case. Or if you decide to use a theme in your case, then you may want to organize it based on what the case is actually about. You may have also reserved your opening statements until the end of the opposing party's case. It's not recommended. It's not done very often, but it is an option. Usually opening statement for about 10 to 20 minutes long, depending on the type of the case. So generally, the more serious the case, the longer the opening statement. So if you have something like a murder case or something like that, that could be an hour, two hours. Also, you may want to check with the local judge, whatever jurisdiction that you're in, and see if that particular judge has-- some judges limit the time that you can actually use an opening statement. So once again, that is something that you would want to find out before the trial date. So the next part of a trial is the plaintiff's case-in-chief. The plaintiff has the burden of proof, so they present first. So each side does an opening. So let's say the plaintiff does their opening, the defense does their opening, then the plaintiff begins their case-in-chief. So the plaintiff calls their witnesses. So what happens first is their witness is sworn in. Let's say, for example, the state of New Mexico v. Smith. What happens is they will present their first witness. The witness will be sworn in. They'll sit in the witness chair. And then the prosecutor in that case, since it's their witness, will do a direct examination. A direct examination is usually an open ended question. So you're not asking leading questions. That's for the defense in cross. But generally, you're asking questions like, what happened, what happened next? And we'll go through that a little bit later in the term. So when the state or the plaintiff is done with their witness, they'll pass the witness. Then the opposing party gets to question the witness. And those particular questions can be leading questions. There's different definitions for a leading question, but it's one that suggests an answer. So you really want to control your witnesses in those cases. And we'll go into that later in the term. But you do want to really limit the testimony. You technically are not allowed to go beyond the scope of direct exam. So what that means in English is that you cannot talk about something that the plaintiff didn't bring up. There are exceptions to that. But generally, that's the rule. So then once the cross examination is done, there's a redirect by the state's attorney or the plaintiff. So they can ask follow up questions from the cross examination. And again, be aware of beyond the scope. Now, when you're doing direct and cross, it's really important to pay attention to evidence and foundation. So evidence allows certain information to come in only if it's considered reliable. So the evidentiary rules say that you need to lay a certain, what we call, foundation in order for certain types of evidence to come in. We will go through the foundations that are required for different types of evidence later in the term. There are different types of evidence. There's demonstrative evidence versus exhibits. Demonstrative evidence don't necessarily need a foundation, there's a little more quantification on that one, but exhibits do. If you intend to have that particular piece of evidence go into the jury room, then you will need to lay a sufficient foundation. Another example of that is judicial notice. So judicial notice says to the judge, well, everybody knows that this is accurate, so we're asking the judge to take judicial notice that it is accurate. It's a fact that can easily be determined and verified. So for example, if a witness said that the temperature on the day of the incident was 73 degrees, relatively easy to pull up a weather website and see if that's correct, that would be an example of taking judicial notice. You can also stipulate with the other party as to foundation. So to save everybody's time, say, hey, can we agree that it was 73 degrees that day on the day of the incident? And if opposing party says yes, then you can proceed without worrying about foundations. So once the plaintiff does their redirect, then the plaintiff rests and the witness is released. And then the plaintiff calls their next witness. So it just continues and continues and continues. So the next part of a trial is motions after a plaintiff rests. So usually, the defense argues a directed verdict, a motion for directed judgment of acquittal, or a judgment as a matter of law. And what they're arguing in this case is that the plaintiff failed to prove a prima facie case. And what that means is "on its face." So what the judge is going to look at is whether or not the plaintiff proved every element of the charge. And so it can be written or oral. And it will be granted if the plaintiff has not proven an element of the case. So that is something that you should expect to happen after the plaintiff's case and be prepared for it. The next part of the case is the defense's case. During this part of the trial, the defense gets to present witnesses, if any. In a criminal case, remember that the plaintiff has the burden of proof. So the defense technically doesn't have to present any witnesses. But in some cases, it does happen. And typically, it involves a direct of the defense witness by defense counsel. Usually, those are open ended questions, things like what happened, what happened next, and then followed up by a cross-examination by the plaintiff. The defense counsel gets another chance to redirect after cross-examination by the plaintiff. Again, watch for beyond the scope of direct. The next part of the trial is the instructions conference. So this is where the parties present jury instructions to the court and the court decides which ones to give to the jury. So the jury, they're not lawyers. They don't have a whole lot of experience with the law. So what we do is we prepare copies of, in some cases, the statutes or jury instructions created by the higher courts that explain the law to the jury. So both parties submit their proposed instructions. And there's an instructions conference where the parties go over the jury instructions together. And the judge decides which ones to select for the jury to take into the deliberation room. Plaintiff and defendant submit proposed jury instructions regarding the law and what the law is and the elements of the charges. Have them prepared well beforehand. You do not want to wait until the last minute, because the judge will be very upset if the jury is waiting for you to prepare a jury instruction. Another thing to keep in mind is you should have the ability to edit the jury instructions immediately in the courtroom. So if you need to bring your own printer, definitely bring the computer where the instructions are or at least a digital copy so that you can access them easily so that you can make any changes the judge asks for immediately. Finally, there's closing arguments. In different jurisdictions, they do the closing arguments and the instructions at different times, the final instructions. But know that, generally, it's towards the end of the trial. Closing arguments-- the best closing arguments, if you are able, have themes in them. Some do, some don't. But generally, it's good to select a theme. And we'll talk about that throughout this term. Again, you're not only going to be talking about the facts in this case but also the law that applies to it. So it's different from opening statements in that you're not only discussing the facts, you're also discussing how those facts apply to the law and the elements of all the charges that the plaintiff has to prove. The jury can consider inferences. And those are the things that you want to point out to the jury. Sometimes you don't have direct evidence. Sometimes you need to help them with those inferences in order to prove your case. You also want to go through any exhibits, testimony, anything you can do to persuade the jury, because that's your final chance to persuade them. The plaintiff argues first. The defense goes second. And then the plaintiff gets to go last, because they do have the burden of proof. And then at this point, like I said, this can happen before or after closing, but generally, the judge will read the jury instructions to the jury and also present verdict forms, which are the forms that the jury fills out when they've decided how they want to rule in the case. The last stage of a trial is jury deliberations and verdict. At this point, the alternate jurors are dismissed. Remember that alternate jurors are selected in case one of the jurors is unable to deliberate. Maybe they were sick. Maybe they didn't appear in court. So if everybody, all of the original jurors are there, then the alternate jurors are dismissed. At this point, the bailiff usually assists the jury into the jury deliberation room. The bailiff is typically there, stands outside of the jury room, only because jury deliberation is secret. And usually if the jury needs anything, they knock on the door, and the bailiff is there to help them with whatever they need. Once the jurors go to deliberate, they're instructed to select a foreperson. And once they decide what the verdict is, then they sign the jury verdict forms and return them to the court. The jury, during the deliberation, may ask questions. They may return a question for the judge and for the parties to answer. The judge and the parties may not always answer those questions, depending on what they are. But the jury is allowed to send questions to the judge and the parties. When they do, the parties usually discuss what response to give with the judge. And the judge makes the final decision and prepares a response for the juror. At the end, once the verdict has been given to the court and actually read to the parties, then the parties have the option to poll the jury. And what that means is that the parties can ask that each individual say what their verdict was, just to make sure there were no errors. It's extremely rare to have an error, but it does happen. And ultimately, an Allen charge encourages jurors to listen to each other and to attempt to reach a verdict. This is usually what happens when the juries tell the judge that they cannot reach a verdict. Remember, verdicts in some cases, specifically criminal, have to be unanimous. So if they're unable to reach a unanimous verdict, it usually results in a mistrial. So after the verdict is read and a judgment is made, there's an argument of judgment notwithstanding the verdict. And it's a request to set aside the jury's verdict and enter a judgment for the other side. The parties can also make an argument for a motion for new trial based on errors made during the first trial. In civil, there's other motions that could be filed as well. But ultimately, what you want to do is check the local rules for deadlines for appeal. If you miss the deadline, it could be malpractice. So it's important to know that. So we have discussed the different sections of a jury trial, specifically the jury selection, also known as voir dire, opening statement, plaintiff's case, including direct and cross, defense's case, direct of the defense's witness by the defense attorney and cross by the plaintiff of the defense's witnesses, closing arguments, jury instructions, jury deliberation, and verdict.