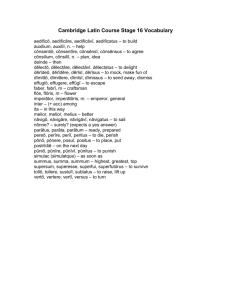

NEWSDAY / THOMAS A. FERRARA NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B2 CHAPTER 1 ONE MAN’S RISE SHINES LIGHT ON LI’S CORROSIVE SYSTEM BY GUS GARCIA-ROBERTS AND SANDRA PEDDIE sandra.peddie@newsday.com NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com S hortly after noon on the nearfreezing day of Feb. 24, 2014, real estate developer Gary Melius started his Mercedes-Benz in the valet parking lot behind Oheka Castle, the palatial Huntington hotel and event center he owns and calls home. A masked man crept from a Jeep Cherokee parked nearby, put a pistol to the driver’s window and pulled the trigger, wounding Melius in the left forehead. In his fragmented recollection, Melius heard a ringing in his ear and staggered to the castle, where he swiped himself in, put a wet towel to his head and asked his daughter to drive him to a hospital, later bragging that he “showed no fear.” His still-unsolved shooting was treated like the attempted assassination of a statesman. Suffolk police officers assumed an imposing guard at the snow-specked castle while a roster of Long Island’s most influential officials at the time visited him at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset. The visitors included the two county executives, Suffolk’s Steve Bellone, a Democrat, and Edward Mangano, a Republican; Reps. Peter King, a Republican, and Steve Israel, a Democrat; former Freeport Mayor Andrew Hardwick; acting Nassau Police Commissioner Thomas Krumpter; Nassau Sheriff Michael Sposato; Nassau’s top administrative judge, Thomas Adams; Suffolk Supreme Court Justice Thomas Whelan; and, overshadowing them all in wide-ranging influence, former Sen. Alfonse D’Amato. The attempted murder in broad daylight of a developer with powerful connections, captured by surveillance footage on his castle grounds, briefly made national news. It loomed larger in Long Island’s political world. Gary Lewi, D’Amato’s former press secretary who has also represented Melius, compared the incident with “Robert Moses being gunned down in the parking lot of Jones Beach.” However overblown the link to the legendary master builder, Melius’ broad reach over Long Island politics, This project was reported and written by Gus Garcia-Roberts, Keith Herbert, Sandra Peddie and Will Van Sant with contributions from Aisha Al-Muslim, Matt Clark, Paul LaRocco, Maura McDermott and Adam Playford. It was edited by Martin Gottlieb and Alan Finder. law enforcement and civic life has in many ways been unparalleled. With a mix of canniness, unpolished charm and threats and taunts, Melius, now 73, has transformed himself from a teenage street tough out of West Hempstead to owner of the castle that became Long Island’s unofficial political clubhouse. His networking has been prodigious, allowing Oheka to flower. He has been the host at years of law enforcement parties at the castle, where, guests said, cops and FBI agents ate and drank for free. His foundation has donated more than $2.8 million to roughly 500 mostly local charities. In addition, Melius, his family, businesses and employees have contributed at least $1.3 million to politicians, several of whom were behind governmental actions worth millions to him. Never a Democratic or Republican functionary much less a party boss, Melius made his way from the outside in — as a player with powerful friends and a practical understanding of the day-to-day workings of Long Island’s cozy, transactional politics. As such, his life reveals a detailed picture of how the system functions. It is a system facing crisis. For decades, scandal has been a steady current in Long Island politics, but last year it blew out fuses. By Newsday’s count, in 2017, about 40 public officials, politicians and cops and other government workers were indicted, imprisoned, or forced from their jobs by ethical transgressions and scandals. That capped a 10-year period with more than twice that number of cases. Among them was Mangano, whom Melius has described as “the best political guy” and whose federal trial is scheduled to begin in March. He is charged with giving government contracts to a restaurateur whose favors included employing his wife, Linda, as a food taster for a total of $450,000 over more than four years; prosecutors allege that she performed little or no work. Mangano and his wife have pleaded not guilty. They also include Edward Walsh, B3 NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION SCPD One man’s rise shines light on LI’s corrosive system Suffolk’s longtime district attorney, Thomas Spota, who, with the head of his anti-corruption unit, was charged with conspiracy and obstruction of justice, accused of helping Burke in the cover-up. Spota, who headed the still-unsuccessful investigation into Melius’ shooting, and his corruptionunit chief, Christopher McPartland, have pleaded not guilty. Ambrosino, Venditto and the other Oyster Bay officials have also pleaded not guilty. Federal investigators have looked into matters involving Melius: One concerning fees that he and associates collected from state court appointments and another involving the Elena Melius Foundation, which is named for his mother. But Melius A scene from a portion of surveillance video that shows the February 2014 shooting of Gary Melius. has never faced political corruption charges and is adamant about his integrity. Three years ago, he said, FBI agents hauled 180 boxes out of Oheka. The FBI has declined to comment. “I haven’t done one thing wrong,” Melius said in a meeting with Newsday editors last April. “The federal government — three years to investigate me — you know what they came back with? Nothing.” “I am a very honorable person,” he continued. “Whatever I say, I do the CONTINUES on B5 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 The year’s indictment roster included John Venditto, who resigned as Oyster Bay supervisor between his two corruption indictments, the second of which also ensnared several past and then-town officials; Gerard Terry, who while head of North Hempstead’s Democrats held down five government jobs and pleaded guilty to not paying income taxes on them; and Hempstead Councilman Edward Ambrosino, a prominent Republican who was indicted on charges of failing to pay taxes on his earnings as an attorney for the Nassau Industrial Development Agency and the Nassau Local Economic Assistance Corp. Capping the year was the indictment and subsequent resignation of newsday.com the influential former chief of the Suffolk Conservative Party, who is serving a 2-year sentence for theft of government funds and wire fraud for golfing, gambling and doing political work when he was supposed to be on the job at the Suffolk County jail. The charges included an instance in which prosecutors said Walsh provided support to Melius at a private business meeting when he should have been working at the jail. Former Suffolk Police Chief James Burke is serving 46 months for pummeling an addict who stole his porn-filled duffel bag and trying to cover up the beating. In arguing for a stiff sentence, federal prosecutors noted that Burke bragged about his actions to fellow cops at an Oheka Christmas party. Former Oyster Bay Supervisor John Venditto Former Suffolk Police Chief James Burke NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com sandra.peddie@newsday.com Long Island was particularly hard hit by corruption scandals in 2017, with about 40 public officials and government employees indicted, imprisoned or pushed from office by ethical transgressions and scandals. This was the culmination of a decade in which more than twice that number of officials, cops and other workers were tarred in episodes that short-circuited the careers of such powerful leaders as former State Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos, former Nassau County Executive Edward Mangano, former Suffolk District Attorney Thomas Spota, former Oyster Bay Supervisor John Venditto and former Suffolk Police Chief James Burke. Mangano, Spota and Venditto are awaiting trial and maintain their inno- cence. The tally seemed to be building steam until it exploded last year. Even judges have been investigated by other agencies, publicly disciplined or dismissed on corruption-related charges. The cost to taxpayers in waste, graft and confidence in government runs high, but it is not only they who pay a price. Honest government workers across Long Island — police officers, managers and civil servants of every stripe — have had to carry out their duties in environments tainted by wayward behavior and the bias of outsized political considerations. In some ways, it’s a product of a New York state of mind. The state ranks highest in the country in the percentage of state legislators convicted of public corruption over the last decade, said Jeffrey D. Milyo, a University of Missouri economist who ANTHONY LANZILOTE HOWARD SCHNAPP Former Suffolk County Conservative Party leader Edward Walsh High-profile year of political corruption BY SANDRA PEDDIE Former State Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos ED BETZ STEVE PFOST Hempstead Town Councilman Edward Ambrosino HOWARD SCHNAPP Former Nassau County Executive Edward Mangano HOWARD SCHNAPP Former Suffolk District Attorney Thomas Spota JAMES CARBONE NEWSDAY / JOHN PARASKEVAS NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B4 has analyzed prosecutions nationwide. He said similar data for prosecutions of local officials is not readily available. Dick Simpson, a University of Illinois political scientist and former Chicago alderman, said corruption endures where machine politics is entrenched. The machines thrive as long as they win elections and control government, ensuring patronage jobs and contracts for the party faithful, as well as opportunities for nepotism. A Newsday investigation last year identified more than 100 current or ex-Nassau County elected officials, top appointees or political leaders with at least one family member on public payrolls at some point since 2015. “Some states in the Midwest have never had a culture of corruption,” Simpson said, citing Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa. “If they have one scandal, involving one legislator, it’s a big deal.” On Long Island, in one town alone — Former North Hempstead Democratic Party leader Gerard Terry Oyster Bay — six current and former officials and contractors and a top political leader were charged with crimes last year. The plethora of indictments and convictions raises a deeper question about whether, rather than being discrete incidents, they are manifestations of a malignant system that spawns an outsized degree of wrongdoing. A corrupt culture reinforces itself, said Harvard Law School Professor Matthew Stephenson, who studies public corruption and runs the Global Anticorruption Blog. “When organizations have reputations for corruption, they tend to attract and retain corrupt people,” he said. “Individuals of high integrity don’t want to work in a corrupt environment, while those who are happy to bend or break the rules for their own gain will be attracted to such organizations where such behavior is known to be tolerated or encouraged.” In other words, he said, “You might even feel like a sucker if you’re a guy who follows the rules.” B5 NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION best I can and nobody got robbed from me.” Melius was asked in April if he would be interviewed substantively by Newsday reporters for this project. He was asked again on Feb. 13 if he would consent to an interview. He responded that he would first want to read all of the stories. Newsday’s policy is not to do so. This past November, voters elected several new office holders who carried the banner of reform, including Nassau County Executive Laura Curran, Suffolk County District Attorney Timothy Sini and Hempstead Town Supervisor Laura Gillen. Melius’ half-century-long rise shows how broad and entrenched the system is and how hard it may be to exact lasting change. But that can dissolve on a dime, and in one infamous case his fierce focus led to the arrest of a man with learning disabilities, Randy White, who unwittingly wound up on the wrong side of one of Melius’ political schemes. Often overshadowed by his restoration of the resplendent Oheka and his munificent charitable donations, this more troubling side surfaces most tellingly in Long Island’s public arena. Benefits of the system Former Freeport Mayor Andrew Hardwick visits Melius at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset. eventually paid White a $295,000 settlement — and was later forced out for doing so. Freeport Village Attorney Howard Colton filed a police complaint in 2009 alleging that Melius threatened to have him indicted, citing Melius’ relationships with the Nassau district attorney’s office and its chief investigator. Colton alleged they were acting as Melius’ “private police force.” ! The Nassau and Suffolk leaders of the influential Independence Party worked as Oheka employees over the years. Melius was named the party’s “chief adviser” as part of an effort to take the party national, and he and his daughter reaped hundreds of thousands of dollars in appointments from a judge whose political career was resurrected by the party. In the mix of Melius’ business associates were: a Howard Beach car thief whose son was killed in a mob hit, a charismatic loan shark, and a Japanese businessman widely reported to have ties to the Yakuza crime organization. Critical of media coverage The incongruities in the arc of Melius’ life have been plentiful, notably the juxtaposition of relationships with Long Island government and law enforcement officials and sporadic associations with unsavory characters. At a meeting with editors last April, Melius criticized coverage of CONTINUES on B6 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 Unfolding in records and interviews is something akin to an American dream success story, albeit of the complicated, less sanguine variety captured in novels such as “The Great Gatsby.” There, the protagonist emerges from obscure beginnings with the help of questionable connections offered by his 1920s Jazz Age circle and achieves a success captured in the grandeur of his North Shore mansion. Melius is a far cry from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s glamorous, tragic protagonist. But for a half-century, Long Island’s world of politics and power has provided him an equivalent circle, supplying connections, opportunities and the playing field of a tumultuous life, grand mansion included. When Melius maneuvered within Long Island’s bounds, he reaped millions through zoning changes, legal settlements, contracts and court appointments. When he tried his luck outside it, he often stumbled through an assortment of failures, from a foray into boxing promotion to trying to partner in casino management upstate and more. Those are stories in themselves, but more importantly they point to what was absent as Melius tried to succeed on his own: the sustaining power of Long Island’s political network. Through Melius, Newsday’s investigation reveals the benefits that system can provide: ! Early on, a young Melius faced five sets of criminal charges, but after he hired a politically connected Long Island lawyer, felonies morphed into misdemeanors, near certain jail time turned into light fines and probation, probation got cut short, and his most serious conviction was expunged. ! As Melius, his employees, businesses and family members were contributing at least $1.3 million to political campaigns, he was lifted out of real estate problems at Oheka and in Freeport through favorable government decisions worth millions. In Freeport, Nassau County bought his failing property based on a questionable valuation commissioned by the county that was three times higher than the property’s assessed value. ! As he feted cops and FBI agents at Oheka, Melius became involved in episodes that called into question the integrity of law enforcement agencies in which his friends held key positions. Melius championed the hiring of Thomas Dale as Nassau police commissioner. Later, he called Dale to say Andrew Hardwick’s county executive campaign wanted to file a perjury charge against Randy White, the man with learning disabilities who had testified in a case that threatened Melius’ bid to influence the 2013 election. Dale had White arrested — on grounds so suspect the county newsday.com As cops, reporters and an array of Long Island power brokers massed outside the hospital where doctors were working to save Melius’ left eye, his friends said they were mystified by the attack. “No one could think of anyone that would want to kill Gary,” Steven Schlesinger, a powerful Nassau Democratic Party lawyer told a television reporter. In many ways, the sentiment was understandable. There are plenty of campaign contributors who send money to politicians, but few who go puppy shopping with them, as Melius did with Mangano. At Oheka, he is known as an affable, self-effacing bon vivant, telling jokes in a blunt cadence while wearing short sleeves that display faded tattoos. And his private enjoyments can be endearing. His fellow up-fromnothing mansion owner John Nasseff fondly recalls dinners with the Meliuses at his Minnesota home where they enjoyed performances by hired singers and magicians. “To know him is to love him,” said D’Amato after visiting Melius’ bedside. But a far more complicated and contradictory picture of Melius emerges in Newsday’s extensive examination. The picture took shape through a mosaic of sources: more than 500 interviews and tens of thousands of pages of records. They include longoverlooked files that cover Melius’ early criminal career; documents from more than 200 often rancorous court cases with business partners, neighbors, government agencies, and even his dry cleaner; an investigation by the National Indian Gaming Commission, a federal agency whose staff recommended that Melius be found unfit to run a casino; and a string of business failures and gambling debts that left his creditors with as little as 5 cents on the dollar. The generosity is certainly there. So is the likable persona recalled by friends. HOWARD SCHNAPP A contradictory picture NEWSDAY / DICK KRAUS Ellen “Chickie” O’Meara in 1976. GALASSO FAMILY him in Newsday, which has published articles about his foundation, receiverships he and his daughter were awarded by judges, and other matters. Melius last year accused Newsday of unfairly attacking him, saying the newspaper had featured him in 170 stories since he was shot — 16 on the front page — that, he said, had exacted a toll on his business and family. Also last year, Melius threatened a Newsday reporter who worked on a story about his effort to get the Nassau County Legislature to approve a sewer hookup for a condominium development at Oheka Castle. He agreed to an interview at Oheka in 2014 with Newsday investigative reporters for this story but declined to discuss many topics. Melius refused further substantive interviews with team members, although he answered some questions from a Newsday business reporter last summer before a legal proceeding began. “I am broke now, I mean I have lost everything, thanks to the paper,” he told the editors last April, explaining his reticence to talk further. “I am none of the things you have me down as. I am not a power broker; I am a nice guy.” Melius’ life is quieter now and he complained to Newsday editors of the fallout from the shooting: seizures and that he can’t drink, smoke cigars or drive anymore. “They only harpoon the whale when he surfaces, and it’s true — look what happened to me,” Melius remarked. “I will never do that again, getting shot in the head.” As for the shooting investigation, Justin Meyers, chief of staff for Suffolk County District Attorney Timothy Sini, said: “We wouldn’t discuss an open investigation but I can assure you it remains open and the police department continues to pursue the case.” Fran Arello in the early 1970s. NEWSDAY / RAYCHEL BRIGHTMAN NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B6 NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com ‘Troubled youth’ Melius’ Long Island story began like many others in the 1950s, when droves of city dwellers, many of them Irish, Jewish or Italian, flooded what had mostly been farmland, more than doubling the Island’s population in two decades. It amounted to a second great migration by families that emigrated from Europe in the 19th and early 20th century. When Melius was in third grade, his family, which included two sisters and an older brother, moved from Jackson Heights, Queens, to a small home on West Hempstead’s Maplewood Avenue. He would establish the multimillion-dollar Elena Melius Foundation in honor of his mother, a daughter of Italian immigrants whom he venerated. He has characterized his father, a truck driver, as abusive, he once told Newsday. As described by his teenage sweetheart, Melius was the most charming Marilyn Brown Ryder in April 2017. rogue on the block. Marilyn Brown Ryder, who dated him when she was 16 in 1960, remembers the handsome, dark-eyed leader of a crew of troubleseeking boys, including her future husband, Robert Ryder, who mostly hung out at the neighborhood bowling alley. “They were the talk of West Hempstead,” she recalled. But while his friends looked for fights, Marilyn Ryder described Melius as something more, smart and savvy and able to “B.S. anyone.” Nonetheless, Melius said in a Newsday interview that he dropped out of West Hempstead Junior High before ninth grade. In 1962, he and Robert Ryder were arrested and charged with petty larceny for stealing tires, according to the staff findings of the National Indian Gaming Commission, which years later chronicled his criminal history as it weighed his suitability to manage a casino. The disposition of those charges is unknown. The next year they were busted for a felony marked by ruthlessness and the incongruous generosity that has typified Melius. Just short of his 19th birthday, he, Ryder and two others “slapped, choked and threatened with death” a West Hempstead hitchhiker from whom they stole $40, according to a Newsday report. But the muggers left their victim with $10 for carfare home. Melius pleaded guilty to felony second-degree attempted grand larceny, according to the Indian commission memo. He was sentenced to up to 5 years, with the penalty suspended, the memo stated, meaning he served no time. Melius has described his criminal past as “colorful,” chalking it up to his “troubled youth.” But criminal records, court transcripts and interviews indicate that he graduated from local hooliganism to more sophisticated schemes, one with organized crime links. Befriending an officer By the early ’70s, Melius was stumbling through what he has called a “whole list of failures,” such as Gary’s Tree Service and Gary’s Pizza Oven, and trying to build a modest contracting company called Eastport Construction. Around this time, Nassau County Police Officer James Mileo later recalled, he pulled over Melius in Manhasset for speeding. Now in his 80s, Mileo told this story from Florida: Melius talked fast, quickly learned that the cop had money woes, and offered him parttime work at Eastport, which Mileo accepted after forgetting about the speeding. Mileo got to know his new boss, and real estate records show that at one point the cop deeded him a house in Seaford. He recalled a day when Melius picked him up at a job and drove to a Brooklyn restaurant. There, Mileo said, Melius joined a man at a corner table whom the cop recognized as Carmine “The Snake” Persico, the Colombo crime family boss whose foreboding, angular features were captured regularly in New York tabloids. After 10 minutes, Melius returned to their table, Mileo said. Mileo said he took the display as at least partly for his benefit. “He wanted to get me on the illegal side of things,” he said. Fran Arello, then a rookie with Nassau police’s organized crime squad, said that a Colombo-affiliated informant reported that Mileo was stealing construction equipment from parkways and shaking down motorists with Melius’ help. Arello recalled scoping out Melius’ contracting storefront in Valley Stream before she donned a red wig and jammed a tissue-wrapped microphone into the bosom of a tightfitting dress one night in September 1971. She drove a Cadillac convertible down Roslyn Road, where her informant had set up Mileo by telling him a heroin courier with a “very rich father” would be driving by. Mileo pulled over the Cadillac, rifled under a floor mat and found packets of milk sugar that passed for the drug, Arello recalled. She said Mileo offered to let her go for $15,000 and then released her to retrieve the cash. After collecting marked bills in an envelope from detectives outside a nearby bank, she went to a meeting point across from a synagogue on Roslyn Road where Melius, whom Arello called the scheme’s “bagman,” was waiting and took the cash, she said. A short time later, he and Mileo were arrested and charged with felony grand larceny. During the episode, there was another person in the car: the mob informant, who sat in the shotgun seat. She was a gangster with a bouffant who ran a racket with three female lieutenants and whom Arello remembered as foul-mouthed, funny and smart, and also as someone who would “shoot you in a heartbeat.” Her name was Ellen “Chickie” O’Meara. O’Meara was a cinematic figure undiscovered by Hollywood. A product of private schools in Queens and Long Island, she traced Mafia ties to her grandfather, whom she described in an interview as an associate of the seminal mobster Vito Genovese. Besides the Colombo family, O’Meara told a reporter she also worked for Gambinos. She had been locked up dozens of times by 1970 for offenses as diverse as lifting fur coats and fixing college basketball games, according to contemporaneous news reports. That summer, according to O’Meara’s later testimony, her primary racket was an interstate theft ring specializing in construction equipment and Cadillacs. She ran it with her three lieutenants and a crew of male worker bees. Word of the operation got around, though, and shortly before the Melius-Mileo busts, O’Meara was quietly arrested and turned; her bid for leniency put her in Arello’s Cadillac on Roslyn Road. Cliff Schmidt, then the Nassau Police Benevolent Association’s second vice president, recalled sitting with Mileo in an interrogation room and his heart breaking as the cop owned up. “He was a great officer,” Schmidt said of Mileo, who he believed was likely “entranced with Melius.” “I wish he would have never have gotten involved with him,” he said. More than four decades later, B7 NEWSDAY / DICK YARWOOD Weeks after Melius and Mileo were arrested, federal and New York City prosecutors moved on O’Meara’s Gary Melius at Oheka in May 1987. O’Meara and others detailed the operation during a related federal trial in Virginia against buyers of her stolen haul. According to her testimony and others’, construction site CONTINUES on B8 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 Testimony on car theft ring entire ring, sweeping up 16 suspects, including Melius again. A New York Times account described the crew as an element of “a much more potent faction of organized crime that operated in many states.” In 1971, Melius faced grim prospects. At 27, he had been arrested five times. The hitchhiker mugging had resulted in a guilty plea to a felony. He still faced judgment day on the cases involving the shakedown of the undercover cop and the car theft ring. And unknown to him, there was a Nassau County judge who wanted him imprisoned. He needed legal magic, and found it in a young lawyer named Richard newsday.com Mileo could not qualify for a job as an unarmed security guard in Florida. Meeting influential lawyer NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION managers were complicit, deals went down under city bridges, and hot machinery was stashed at a Sheepshead Bay marina. Witnesses testified of threats and visits from O’Meara’s intimidators, her demands for money she said was needed to pay off a judge and an apparent attempt to burn evidence as authorities closed in. Granted federal immunity for her testimony, O’Meara used simple terms to describe Melius’ role. “He is the one who steals the Cadillacs,” she testified in court. With car theft rampant on Long Island and often mob-controlled, O’Meara and others described the street outside Melius’ home as lined with stolen, nearly new Cadillacs. She recounted a negotiation at a motel near LaGuardia Airport, where a couple of out-of-state businessmen attempted to pay for a Cadillac with a cashier’s check. “Gary said they wouldn’t take no check, that they would only take cash,” O’Meara testified. When the buyers returned with proper payment, Melius and an associate identified only as Pauley led them to his fleet, O’Meara testified. “Gary gave me the keys to give them,” O’Meara said. “They gave me the cash in an envelope, and Gary counted it out, and that was it.” O’Meara served 3 years in prison. Upon release she found a home in Long Island politics. She became an aide to then-state Sen. Karen Burstein of Woodmere, who said O’Meara caught her eye as a leader in prison reform from the inside. Burstein said that she believed that O’Meara “might still be friendly with some people,” but was through with the rackets. That may have been a miscalculation. In 1976, O’Meara was arrested and charged with soliciting a cash bribe in exchange for using her position to help secure parole for an inmate, according to a news report. The bribe allegedly was paid directly to her bookie. O’Meara was found guilty, but the conviction was overturned because of a wiretap the courts ruled illegal. Along the way, she found Judaism. She died last year, said her rabbi, Yitzchok Frankel. NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com NEWSDAY / STAN WOLFSON Richard Hartman in 1976. HOWARD SCHNAPP Hartman. Hartman was a well-connected, self-destructive math genius who was born a Brahmin in Long Island politics. His father was William Hartman, a one-time state senator, GOP committeeman and aide to Assembly Speaker Joseph Carlino. Carlino was a seminal leader of Nassau’s formidable party organization, which at one point caused Ronald Reagan to beam, “When a Republican dies and goes to heaven, it looks a lot like Nassau County.” Before his father pushed him into law, Richard Hartman dreamed of teaching mathematics, his sister Lynn Alpert said. He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology but left before graduating and then earned a degree at New York Law School. He worked briefly as a Nassau prosecutor and a lawyer in traffic court, where Melius met him. Soon, though, he leapt into representing the police unions that cover both Long Island county departments and influence life — and taxes — here to this day. He also represented dozens of other unions, politicians and mobsters. Among the latter was an admitted contract killer named John Alite, a mob associate who became a witness for federal prosecutors. In an interview with Newsday, Alite described Hartman easily arranging a plea deal that kept him out of jail for carrying a handgun in an Island Park nightclub. He said he still recalls how Hartman explained his success: “It’s who I know, it’s not what I know.” Hartman’s headquarters at 300 Old Country Rd. in Mineola was a white stucco building recalled as a dump by nearly everybody who encountered it. Melius’ contracting company eventually became a tenant. Hartman’s unmarked domain, a raucous all-hours hub of political power, was on the second floor. A secretary, Patricia Phillips Hartman, no relation to her boss, whom she called “maniacal,” recalled: “He would pound on the desk and yell for a girl. ‘Girl! Girl!’ Everybody would bump into each other trying to get into that office quick enough.” Former Suffolk Police Commissioner Gene Kelly, who worked briefly for Hartman, said he “never had a clock” and would call on work matters at 3 a.m., something that drove some to quit. Hartman’s then-girlfriend, Patricia Motamed, a secretary on the overnight shift, recalled that as his practice grew, Hartman hired so many new attorneys that Melius was enlisted to build each an office on the roof. “It really looked like a shack and a dump,” Motamed said. She also measured the fast-forming friendship between the on-the-rise police lawyer and his frequent client. Alfonse D’Amato in 2014. NEWSDAY / TOM MAGUIRE NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B8 William J. Sullivan in 1963. “You have two people who collided, one who was brilliant, almost a savant,” said Motamed, “and one who was a true, local thug.” Change in fortune The vagaries of record retention and sealed files concerning decadesold cases make it impossible to ascertain Hartman’s full representation of Melius. What’s clear is that after meeting Hartman, Melius was the beneficiary of numerous fortuitous legal developments. His 1964 felony plea in the hitchhiker case was a seemingly indelible mark. But in September 1970, nearly seven years later, it disappeared, according to the Indian Gaming Commission memo. The outcome of the case was erased and records of it sealed. Melius was the unusual beneficiary of a statute that was touted as a means of helping teenagers start fresh after an early arrest. Melius was a good deal older in 1970 — 26 — and the statute makes no mention of a retroactive youthful adjudication, which the federal memo stated he received. And at the time, according to O’Meara’s testimony, he was stealing cars for her ring. Under the statute, a candidate for adjudication had to be recommended by a district attorney, grand jury or judge and investigated by a probation agency. Because the records are sealed, it’s unknown who recommended the treatment in Melius’ case, but the circumstances were noted by Nassau County Judge William J. Sullivan when Melius appeared before him on St. Patrick’s Day 1972. He was awaiting sentencing in the attempted shakedown of the undercover police officer, for which he had been charged with grand larceny, according to court documents. Melius had agreed to a deal in which he would plead guilty to a misdemeanor. Melius’ lawyer, Theodore Daniels, argued for probation. But that day, Sullivan received a probation report describing Melius as unreformed. In scathing remarks reflected in a court transcript, he told Melius, “The probation report indicates you still keep undesirable company, that you are greedy for money, and I am satisfied that you are the one that got your co-defendant in trouble.” The judge called the erasure of Melius’ felony in the hitchhiker’s mugging a “break,” but, he told him, “You didn’t learn anything from that.” Despite the plea deal, Sullivan said, “I think that the only way to straighten you out and to get you away from the associations that you have been keeping, is to take you out of circulation for a short while.” Facing certain jail time, Melius withdrew his guilty plea and turned to a new lawyer, Hartman. Sullivan was a rare Democrat among Nassau judges. In Hartman, Melius retained a lawyer with deep GOP connections. By the next court date a month later, Sullivan had been replaced by a new judge, Albert A. Oppido, a Republican. The change of judges is not explained in surviving court records, and both Sullivan and Oppido are deceased. A transcript shows Oppido taking a stance diametrically opposed to Sullivan’s. The judge allowed Melius to plead to misdemeanor attempted grand larceny in the third degree, according to court documents. He sentenced Melius to 3 years’ probation and a $1,000 fine. The National Indian Gaming Commission memo shows Melius again the benefactor of lenient sentencing in Queens, where he faced felony charges including criminal possession of stolen property for his role in O’Meara’s ring. Melius pleaded guilty to misdemeanor conspiracy and was fined $500. Citing FBI records, the memo recorded one last arrest by Nassau police in October 1971, that led to grand larceny charges, which were dismissed. The memo did not describe the activity that led to the arrest or why the charges were dismissed. By February 1974, Melius’ arrest record had resulted in no known prison time, with his single felony conviction erased, according to the federal gaming commission memo. It totaled his fines at $1,500. Melius bore one last legal burden: more than a year still left on his probation resulting from his attemptedgrand-larceny plea in the shakedown of the undercover cop. This was more than an inconvenience. Probationers sometimes receive surprise home visits from probation officers and risk jail for any B9 BY SANDRA PEDDIE sandra.peddie@newsday.com ALL ISLAND AERIAL / KEVIN P. COUGHLIN of her old boyfriend. “That was all Richard,” she said. “He fixed all that.” The probation department recommended Melius’ discharge and Oppido signed it. The once-accused Cadillac thief and shakedown artist left Nassau Supreme Court an unencumbered man. Long Island power established Three decades later, developer Wilbur Breslin and his lawyer drove to the same courthouse to do battle with Melius, by then also a prominent developer. In the parking lot, they noticed Melius’ car in the chief judge’s spot. “We’re dead,” Breslin recalled saying. The sinking feeling intensified in Judge William LaMarca’s courtroom, where Melius and his lawyer were seated. As Breslin remembers it, the courtroom door swung open and in came a robed judge who greeted Melius with an enthusiastic: “Hi, Gary!” Then the door swung open again, and another smiling face emerged — that of Al D’Amato. He delivered kisses to LaMarca, Melius and Melius’ attorney, Marlene Budd, Oheka Castle in November 2010. according to an attorney who was there. Melius had sued Breslin, seeking repayment of a loan and a broker’s commission, on which Melius said they had orally agreed. As Breslin had gloomily forecast, the case went south for him. In his ruling in 2005, LaMarca said contradictory testimony by Breslin and Melius left him having to weigh whose was more believable. He said he found Melius a “more credible witness” based on other witnesses’ testimony. Breslin appealed the award of the loan, and a state appellate court in Brooklyn overturned LaMarca’s decision, finding that Melius’ argument hinged on a complicated “kickback scheme, which was illegal and unenforceable.” LaMarca’s decision on the loan, they determined, was “contrary to the weight of the credible evidence.” It was a loss for Melius, but it proved a contrary point: His influence on Long Island had grown far more than could have been expected once upon a time. NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 violation. Escaping the obligation required a recommendation from probation officials who two years earlier had found him unreformed, and then a judge’s OK. Hartman was familiar with the heavily politicized department. His sister was an officer there and he would represent its union for years. In February 1974, Melius was the subject of a new probation department report that noted a remarkable transformation. It concluded that he had “demonstrated a complete change of attitude and behavior,” and had “concrete roots in the community and is seen as a responsible father and citizen. He is conscientious and ambitious with his business.” The author of the report was John Siarkowski, a longtime probation officer who has been active in the Republican Party. He declined to comment for this story. One of those signing off on it was Daniel Ebbin, the now-deceased longtime chairman of the probation officers’ union. Perhaps there was truth to the report, but when told of it, Motamed said she recognized the handiwork newsday.com In the early 1970s, the Nassau County Probation Department was highly political, in part because there was no Civil Service test for positions, according to former employees. Anyone seeking a job in the department needed a referral from Nassau Republican headquarters. “It was strictly political,” said Stephen Goldberg, who retired as assistant director in 2015. Candidates would be asked in job interviews, he said, “Who’s your committeemen? Who sent you?” Michael Vicchiarelli, former president of the probation officers association, said, “If you wanted to be a probation officer in Nassau County prior to the creation of the unified court system, you had to have a referral to Post Avenue,” the location of Nassau Republican headquarters in Westbury. The unified court system is the administrative arm of the courts. Today, there are Civil Service rules governing jobs in the department. Louis Milone, who ran the department in the 1970s, was a Republican executive leader for Rockville Centre and the brother-in-law of Ralph Caso, the Nassau County executive from 1970 to 1978. The current Nassau Republican leader, Joseph Mondello, began his career as a Nassau probation officer before he went to law school. Richard Hartman, a well-connected attorney, was known for his ability to obtain favorable terms for clients trying to avoid jail time for criminal offenses, according to several who worked with him. Hartman, who represented scores of law enforcement unions, later represented probation officers. “If you wanted to get a good probation deal, you went to Richie,” said Lewis Kasman, a former Hartman intern and Caso aide. One beneficiary of Hartman’s legal finesse was Walter Cox, a Republican committeeman who, while driving drunk, crashed his car into a supermarket and stole $881. With Hartman representing him, Cox avoided jail time and even had his sentence — 5 years of probation — reduced to 2. He later became Hartman’s investigator on police union cases in New York City, until he was imprisoned after being convicted of impersonating a federal lawman in an effort to derail an extortion case against a congressman and four Oyster Bay officials. NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION Therolethat politicsplayed inNassau probationin’70s B10 CHAPTER 2 NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION DEALS, COP CONTRACTS: LEARNING FROM THE MASTERS BY SANDRA PEDDIE AND MAURA MCDERMOTT sandra.peddie@newsday.com maura.mcdermott@newsday.com NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com I n the years after 1974, when he put his last criminal conviction behind him, Gary Melius launched a career that saw him buy, sell, renovate, build and manage more than a million square feet of property. At critical moments, he received public help worth millions of dollars from officials to whom he gave campaign contributions and favors. During the same period, Melius’ first great mentor, the late lawyer Richard Hartman, negotiated a series of police contracts unprecedented in their generosity that to this day inflate Long Island’s outsized taxes. Last year, 1 in 4 officers in the two county departments, or more than 1,300, earned over $200,000. In New York City’s department, which is 10 times larger, the comparable figure was 48, or 1 in 1,000. And another major Melius ally, Alfonse D’Amato, after a controversial tenure as Hempstead’s presiding supervisor, won election to the U.S. Senate in a giant upset. D’Amato toughed out an investigation into kickbacks by town employees to the Republican Party; allegations of favoritism in placements into subsidized housing in his hometown, Island Park; and a district attorney’s report that concluded politically connected developers had received below-market leases on valuable properties in Mitchel Field. In 2003, the U.S. courthouse in Central Islip was dedicated in his name. In the go-go period between the mid-’70s and mid- to late ’80s, each of these men struck out audaciously, catapulting themselves beyond all expectations. The deals and practices of the time illuminate how the burgeoning suburban landscape of Long Island became home to a brand of politics usually identified with big-city machines. It featured a kickback regime in which government workers in Nassau paid the Republican organization 1 percent of their salaries in exchange for raises or promotions; the rewarding of political contributors, connected lawyers and favored contractors with government largesse worth millions; and the power of emerging public unions over political careers at contract time. For Hartman and D’Amato, the decade marked a coming of age. For Melius, the decade held a neophyte’s education in a system he fit into well, in no small part because he made his connections to Hartman and D’Amato just as they were leaving indelible marks on Long Island. Desmond Ryan, the now-retired executive director of the Association for a Better Long Island, the real estate industry trade association, found that despite experiencing Melius’ wrath at times, he had to give him his due. What he recognized, in a way, was something akin to Hartman’s brainpower and D’Amato’s guile. “He methodically reinvented himself,” Ryan said. And that, he concluded, “in itself is an act of genius.” Melius and his mentor Melius moved his construction business to the ramshackle two-story stucco building at 300 Old Country Rd. in Mineola where Hartman, the insomniac lawyer who represented him, ran his law office 24 hours a day in a near-crazed manner. The office was a beehive. There were up-and-coming attorneys, like Anthony Capetola and Michael Axelrod, who eventually became political players. And there was a rolling cast of characters, including a Republican committeeman who eluded jail, with Hartman’s help, after he drunkenly crashed his car into a supermarket and stole $881. Melius hung out at Hartman’s law office, too, and met his future wife, Pamela Robb, an office secretary and an NYPD sergeant’s daughter. Hartman and Melius — both gamblers — became confidants. Patricia Motamed, Hartman’s for- mer girlfriend and secretary, said she remembers Melius answering Hartman’s calls from Atlantic City asking for cash when he was on gambling benders. “Sometimes, when the losses got so great, he would call up Gary, and Gary would fly down with a satchel of $250,000,” she said. James Mileo, a Nassau cop who was arrested with Melius in 1971 in an extortion case, said he once witnessed Melius, at Hartman’s request, retrieving $500,000 from Hartman’s home to take to him when he was hospitalized. But when dealing with politics and his union clients, Hartman’s political acuity and canny negotiating skills were unrivaled, and Melius was there to take it all in. B11 NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION NEWSDAY / STAN WOLFSON Deals,copcontracts:Learningfromthemasters sors wrested contract negotiations from him, and the police unions staged sickouts and packed board meetings. Francis Purcell beat Caso in the next Republican primary. Hartman, D’Amato and the GOP flourished, with the police unions standing by them. The Suffolk PBA followed suit, hiring Hartman and winning comparable pay and benefits. Soon the New York City PBA was knocking on Hartman’s door with a $750,000 retainer. “That changed everything,” Motamed said. “The money just started rolling in.” For Long Island taxpayers, it started rolling out, with police negotiations often setting the pattern for talks with other government unions. Lawyer Richard Hartman in 1976. In more recent times, both the Nassau and Suffolk police unions have made modest concessions, such as in scheduling. In 2012, the Suffolk union agreed to a two-tiered pay scale, with new officers earning less. Still, such concessions have not had a major impact on the overall cost of policing on Long Island. Even with some trims in union contracts, Suffolk faces a budget gap of about $150 million. Since 2012, it has eliminated 1,000 full-time government positions, as well as health centers and the county nursing home. Since 2000, Nassau has suffered the CONTINUES on B12 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 more overtime opportunities and unused time added to pension calculations. By 1975, police costs had increased by 250 percent in only five years, forcing a near-record property tax hike. A Newsday analysis found that the Nassau police ranked lowest in days worked and highest in pay among the country’s 24 largest departments. The combination of a 59 percent pay increase over the previous five years and a reduction of 29 workdays fueled the skyrocketing costs even as crime rates were dropping. It got to be too much for Ralph Caso, the Republican county executive. But, with powerful support from D’Amato, then the Hempstead Town supervisor, the GOP-controlled board of supervi- newsday.com Public employee unions were new to Long Island in the late ’60s. Few people had experience negotiating union contracts. Hartman, though, learned fast and won a succession of benefits from willing politicians who understood the unions’ growing political power. In 1969, Hartman landed the Nassau PBA as a client through his father, a well-connected Republican politician, according to longtime labor lawyer Thomas Lamberti. He soon proposed not just pay increases, but also costly benefits buried in the fine print, like a reduced workweek — a critical detail not made public until after it had been approved. Over the years, the print only got finer — additional night differential, NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B12 ignominy of having to have its budget overseen by a state financial control board, a measure usually reserved for the state’s poorest and most troubled cities and counties. In December, the control board took the drastic step of ordering the county to make $18 million in spending cuts. Last year, the county couldn’t provide the control board with definitive copies of its police and other union contracts. The county explained that the provisions, first engineered by Hartman in a maze of deals, were spread among too many contracts, codicils, side agreements and addenda. Perhaps incongruously, it was Melius, in an interview with Newsday four years ago, who addressed the effect of the police contracts. “They shouldn’t be getting what they’re getting,” he said. “They’re robbing the public.” NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com Real estate portfolio Melius said he became part of Hartman’s entourage in New York City, telling a Newsday reporter in 2014 that he was so vital to PBA representation that he had a parking spot at City Hall. He became more entwined with Hartman in other ways. In 1975, Melius bought his building at 300 Old Country Rd., which was a prime location, for $332,000, sweetened by a $325,000 loan from Hartman, records show. His real estate career began to take shape. As was the case with other subsequent deals by Melius, 300 Old Country Rd. was the subject of transactions that on their face were hard to understand. In 1979, Melius sold the property for $69,000 to Capetola, Hartman’s partner and Melius’ lawyer or partner on other transactions. A year later, Capetola sold it back to him for even less money — $54,000. Real estate professionals say that sale prices on commercial properties sometimes depend not only on market value, but on occasion also can reflect strategies to minimize tax liabilities. Melius demolished the building and erected a 76,000-square-foot office condominium complex. He would later offer the condos for $235 a square foot, which, if he was successful, would have brought in about $17 million. Records do not indicate how much he made. Melius was on his way as a developer. He built a portfolio characterized by the sort of blandness that wouldn’t win architecture awards but was profitable in Long Island’s booming early ’80s market. “It was timing and luck,” Melius told a Newsday reporter. “You bought something — the next day you sold it, and you made a million dollars.” In Great Neck, he built six lowslung brown office buildings that he later described as “six of the ugliest buildings designed by man.” The law firm representing him on the development included Capetola; D’Amato’s brother Armand; Jack Libert, who was then also counsel to the Nassau Board of Supervisors; and Joseph Famighetti, a former member of the now-defunct Long Island State Parkway Police who over the years represented the Suffolk PBA, politicians and their family members. Melius paid under $600,000 in 1984 for a property in Mineola where he built 44 condos, records show. He sold one unit to Famighetti for $130,000. If the others on average went for a similar price, the sales would have netted him $6 million. In 1985, Melius paid $1.7 million for a site on Merrick Avenue in Westbury, constructed a squat office building and sold it in 1988 to his friend John Nasseff’s West Publishing company for nearly $12.8 million, according to property records. Famighetti, Melius’ longtime friend and sometime lawyer, served as West’s attorney. Though Melius played down his acumen — he once stated in a sworn deposition, “I’m not too bright” — others noticed the opposite. “He’s the smartest person in the room,” real estate broker Stephen Caronia said in an interview. “He understands people. He understands how they think. He understands their motives, and he’s got an innate, unteachable sense of how to get things done.” Over the years, Melius built a web of more than 100 corporate entities, a typical tactic of smart real estate players that serves to contain the debt to individual properties. Sometimes, he changed ownership on paper, by transferring a property between two of his companies. Tax returns he submitted to the court when he sued his former accountant show large sums of money flowing into his companies and being quickly redistributed to affiliated companies. Turning to various lenders For financing, he established a collection of sources, from major banks to less conventional lenders. Some were prominent banks, like the Bank of New York. Another lender was Ivan Kaufman, now chief Alfonse D’Amato, then a U.S. senator, with President Ronald Reagan at a fundraiser in March 1984 at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in Manhattan. NEWSDAY / ALAN RAIA Nassau County GOP leader Joseph Margiotta in January 1982. held a weighted vote based on his town’s population, and Hempstead was far and away the biggest town. By 1977, D’Amato became presiding supervisor of Hempstead, which gave him the highest number of weighted votes on the county board. From his hometown of Island Park to the deep corners of county government, sweetheart deals abounded during D’Amato’s tenure. In Island Park, where he still held great sway, 21 poor black families were evicted from a building in 1975 after the village refused to issue permits for the landlord to rehabilitate it. The village replaced it with subsidized housing that was filled with politically connected residents, including the in-laws of D’Amato’s cousin, according to an audit by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Years later, in a civil lawsuit filed by the U.S. Justice Department, former Village Clerk Harold Scully said in a deposition that D’Amato was the behind-the-scenes mastermind in the episode, according to news reports of the time. D’Amato frequently called with instructions, occasionally identifying himself only as “God,” according to the news reports. At a news conference he gave as a U.S. senator, D’Amato said he had no role in any favoritism and praised the village. “It was a great effort on their part and a wonderful program for those families,” he said. In a statement issued in 1990 by his press secretary, Zenia Mucha, D’Amato said, “Dredging up allegations that in fact are untrue and go back as far as 25 years is totally outrageous and doesn’t deserve a response.” While supervisor, D’Amato placed CONTINUES on B14 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 As Melius made his way, so did Alfonse D’Amato. He began his career in Hempstead Town, the heart of Nassau’s Republican machine, running political campaigns and catching the eye of the county Republican leader Joseph Margiotta. Margiotta invited newcomers from the city to join Republican clubs, attend barbecues and lick envelopes; and he rewarded them with jobs, which he, rather than the county executive, controlled. In return, he expected loyalty. The party demanded kickbacks through a regimented system in which workers seeking promotions and raises paid the party 1 percent of their salaries. The kickbacks were challenged in two court actions. In one, Nassau and Hempstead Town workers filed a class-action lawsuit demanding the return of money they had paid to secure jobs and promotions. In the other, federal prosecutors pursued a criminal case that resulted in the indictment of seven former or current Hempstead Town Republican officeholders. In 1975, D’Amato was subpoenaed by a federal grand jury probing the 1 percent kickbacks. He testified that he couldn’t recall collecting such payments, and he was not among those indicted. Years later, a note D’Amato had written surfaced. In it, he wrote that a sanitation worker’s raise would be approved “if he took care of the 1%.” In a 1980 interview, D’Amato defended the note, saying he was merely trying to help the worker. Of the 1 percent payments, he said, “It was a very common practice at the time.” More than 1,000 Nassau and Hempstead Town workers seeking refunds came forward to say they had paid the kickback. The Republican Party agreed to settle the class-action suit, returning money that the workers had paid in return for jobs and promotions. In the criminal case, three Hempstead Town officeholders were convicted of illegally soliciting political contributions from town employees. D’Amato became supervisor when the Republicans used the tried-andtrue political tactic of appointing loyalists to open elected offices so they could then run as incumbents. Margiotta tapped D’Amato in 1969 to run for receiver of taxes. As described by D’Amato in his memoir, Margiotta named him to the powerful post of Hempstead Town supervisor 23 seconds after he was elected. The position had become open when the incumbent, Purcell, had been elected presiding supervisor on the same ballot. In those days, Nassau was run by a board of town supervisors rather than a county legislature. Each supervisor newsday.com executive of Arbor Realty Trust of Uniondale. Melius has said he met the mortgage executive more than 25 years ago when Kaufman found space in the Westbury office building Melius had built. Records show that Kaufman, who declined to comment for this story, has lent Melius more than $50 million through private companies he controls, even when Melius was going through tumultuous business times. “When I first met Ivan, probably know him a year, he lent me $9 mil- From supervisor to senator NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION AP / BARRY THUMMA B13 lion without a document,” Melius said in a Newsday interview several years ago. “OK, two weeks later, he made the document.” The loans involved Oheka Castle, which Melius bought in 1984, and other important properties. Among Melius’ less conventional real estate partners was someone who ran a Long Island office of a brokerage that the Securities and Exchange Commission accused of running a phony “boiler room” stock operation, and who was later barred from any supervisory or ownership role in the securities industry. Another partner was a key witness in an epic mob trial, later convicted of loan-sharking. Teddy Moss was Melius’ partner on a three-story walk-up at 157 E. 55th St. in Manhattan. Moss provided critical testimony in the ’60s trial in which Mafioso “Crazy Joe” Gallo, a tabloid staple, was convicted of attempted extortion and served 9 years before being gunned down in a brazen Little Italy rubout. In an interview, Moss’ widow, Goldie, recalled family trips to Oheka and said that Melius settled accounts fairly with her after her husband’s death. Among other lenders were Melvin Ditkowich and Vytautus Vebeliunas. Ditkowich figured prominently in an investigation of a New York City judge who was removed from the bench after arranging high-interest loans from Ditkowich to private clients in his chambers and not reporting his commissions to the IRS. Vebeliunas, prominent in the Lithuanian-American community, beat a mortgage fraud charge in 1987 but was convicted in 1992 of stealing $8 million from the Lithuanian credit union he controlled, according to court records. Melius’ holdings stretched at their most expansive from suburban Chicago, where he planned a 1,000-unit residential development, to Maryland, where he purchased an 800-unit apartment complex. On Long Island, Melius bought and sold at least 13 properties. NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B14 Hempstead tax revenues in non-interest-bearing accounts at the Bank of New York when banks were paying 10 percent interest on deposits. A state grand jury, while handing up no indictments, issued a report in 1979 that found such deposits by tax receivers in Nassau’s town and city governments had cost taxpayers $6 million. That figure was peanuts compared with the bargains given to the politically wired at Mitchel Field, a decommissioned air base owned by the county. In the late 1970s, Nassau officials started granting 99-year leases there. An investigation by District Attorney Denis Dillon identified the leases as the biggest giveaway in Nassau County history, costing taxpayers an estimated $2.7 billion over the span of 99-year lease terms. D’Amato declined to be interviewed on this and other matters for this story. Dillon’s report said D’Amato took charge by negotiating the first lease, with United Parcel Service, which set the standard for two dozen more, almost all arranged through politically connected lawyers, with belowmarket rents and highly favorable terms to the companies. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, a market-rate rent on such a deal was $20,000 an acre, former Nassau Deputy County Executive James Nagourney said in an interview. UPS leased the property for about $9,500 an acre, with annual rent escalators of 5 percent, rather than the standard 10 percent. The Nassau Board of Supervisors approved the lease. As presiding supervisor of the largest town, D’Amato had the most votes on the board under the weighted system, and no lease could be approved without him. D’Amato said his office had “absolutely nothing to do with the leases” and described Dillon’s report as “totally inaccurate.” But in a recent interview, Nagourney, who was deeply involved in the Mitchel Field project, said he was still troubled by the lease, which he described as a “giveaway.” “The whole pattern for Mitchel Field was set by D’Amato,” he said. None of this stood in D’Amato’s way as he launched his remarkable challenge in 1980 to Sen. Jacob Javits, a liberal Republican icon. Some of it even helped. Lawyers and developers involved with the Mitchel Field leases ponied up with contributions. Among them were William Cohn, Armand D’Amato’s partner; Margiotta; and Libert, who was then counsel to the board of supervisors. Among the developers were Wilbur Breslin, Alvin Benjamin and Nathan Serota. In that first campaign, they gave Alfonse D’Amato at least $16,500, or $47,000 in today’s dollars. By 1986, they had given him a total of at least $47,775, which would be worth $106,000 today. The Bank of New York, where D’Amato had deposited millions in Hempstead Town funds in no-interest accounts, gave his campaign $130,000 in four no-collateral loans at 10.5 percent interest. The prime lending rate in 1980 ranged from 11.5 percent to 20 percent. After federal authorities opened an investigation, D’Amato said he probably should not have sought the loans. No charges were brought. Money mattered, but so did human capital. According to Republicans from the time, the police unions, mobilized by Hartman, turned out volunteers for phone banks and held rallies — a huge boost for a candidate running against the state party establishment. “Everybody was working,” said Lewis Kasman, who worked for Armand D’Amato and Hartman at various times. Records from Alfonse D’Amato’s earliest Senate fundraiser show that nearly half the donors had ties to Hartman, including his brother-inlaw, Bruce Alpert, who served as the campaign’s counsel. In an interview, Kasman, who later turned federal informant after running mob-connected nightclubs, remembered breaking down donations into smaller amounts to evade federal limits. As for Melius, he “was always good for cash,” he said. D’Amato needed “walking-around money,” and Melius would provide it, he said. Melius’ earliest contribution to D’Amato listed in available files shows him giving $1,000 in January 1980. From there, political donations became a way of life for Melius. Melius also rented office space to D’Amato’s campaign at 300 Old Country Rd. in 1983, according to campaign records. By D’Amato’s last campaign in 1998, filings show Melius and his family had cumulatively contributed a total of $17,000 to the senator, among the largest amounts tied to any individual donor. That was a small part of at least $1.3 million in contributions made by Melius, his family, his businesses and employees to dozens of politicians over the decades. They would include at least $61,300 to then-Suffolk County Executive Steve Levy, $33,200 to then-Rep. Steve Israel, and $21,400 to then-Nassau County Executive Edward Mangano, among others. Melius has given to Democrats, including Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo and Rep. Kathleen Rice; Republicans, like Rep. Peter King and then-President George W. Bush; Conservatives, among them then-Suffolk Sheriff Vincent DeMarco and then-Judge Ettore Simeone; and Independence Party members, like Brookhaven Town Clerk Donna Lent and Hunting- ton Councilman Eugene Cook. The number of beneficiaries and dollar totals are likely far higher because records for local campaigns are available only as far back as 2006 and state and federal records go back only to the late 1980s, leaving much of his record inaccessible. D’Amato achieved his surprise primary win in 1980 after mocking Javits’ age and health, and he triumphed in the general election when the liberal vote split between Javits, then 77, who stayed in the race on the now-defunct Liberal line, and Rep. Elizabeth Holtzman (D-Brooklyn). He held his celebration in Island Park, at Channel 80, a nightclub managed by Kasman and owned by Phil Basile, Kasman said. Basile was later convicted of conspiring with organized crime figures. His wife, Angela, contributed $2,000 and volunteered on the campaign, campaign records show. Four years later, D’Amato was the sole character witness for Basile at his trial, where he was accused of conspiring with Lucchese capo Paul Vario to help secure parole for the mobster Henry Hill by setting up a no-show job. Hill’s life was portrayed in the movie “Goodfellas.” After D’Amato left the stand, he embraced and kissed Basile. Basile was convicted and sentenced to 5 years’ probation, plus a $250,000 fine. B15 Long-lasting cost of police contracts NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION BY SANDRA PEDDIE NEWSDAY / ALAN RAIA Mitchel Field, once an air base, in 1981. In a campaign debate in 1980, D’Amato was asked about Basile. He said Basile was someone “I had known as a hardworking family man.” Cultivating connections Richard Hartman with PBA leaders in Mineola in August 1976. “When he was on top of the hill, he was the most powerful lawyer in the state of New York.” Over time, Melius began to distance himself from his longtime mentor. The ill will between them grew, and Hartman maneuvered to push Melius away from the city PBA, flagging his criminal past to union leadership. Melius felt betrayed. “I was trying to hang out with what I thought were good guys, lawyers, law enforcement,” he told the Village Voice. “I would have done better with the bad guys.” Hartman’s gambling addiction eventually overtook him. He was forced to surrender his law license after being charged with misappropriating union money. Then, federal prosecutors indicted Hartman for racketeering, tax evasion, fraud and other charges. He was convicted in 1998 of being part of an elaborate kickback scheme in which he and his associates received lucrative professional contracts in return for payoffs to leaders of the city’s Transit Authority PBA. Hartman spent nearly 5 years at a low-security federal prison in Pennsylvania. After his release, he taught math at Christ the King High School in Queens. Melius, in an interview with Newsday reporters in 2014, said he hadn’t spoken to Hartman for “20-something years” but had eventually reconciled with him. He described the man who had helped resolve his early criminal cases as “a broken-down suitcase.” Hartman died of lymphoma in 2015. NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 CONTINUES on B16 increase in pay and benefits in 1975, making Nassau police the highestpaid in the country. Caso began a two-year court battle but was outmatched. Hartman held police rallies, while D’Amato led a palace revolt. In September 1976, the board of supervisors took control of the negotiations away from Caso and approved a 9.5 percent retroactive raise. In 1978, Hartman won yet another pay increase — 24.5 percent over three years — from an arbitration panel. The size and circumstances of the raise prompted Gov. Hugh Carey to call for an investigation. Joseph French, who cast the swing vote on the arbitration panel, was Hartman’s longtime friend and client. During the contract arbitration, French and Hartman had discussed a real estate dispute French was involved in. Despite their close relationship, then-Nassau County Attorney Edward McCabe, backed by D’Amato, concluded the county should not challenge the contract awarded by the arbitration panel. That paved the way for later police contracts, which today contain six-figure salaries and generous benefits. Lamberti estimates that it costs about $300,000 a year to put a police officer in a car. Before long, Hartman represented nearly 100 law enforcement unions, including the biggest of them all, the New York City PBA, where he brought Gary Melius along as an aide. “Richard was somebody everybody idolized,” Richard Lerner, Hartman’s former partner, said in an interview. newsday.com As D’Amato and Hartman surged, so did Melius. By 1983, he no longer listed himself as “contractor” on campaign contribution filings. Instead, he was the senator’s “Liaison for Police and Fire.” He boasted to Newsday that he negotiated the New York City PBA, fire and correction officers contracts, though the late James Hanley, who oversaw New York City’s labor negotiations at the time, said Hartman handled the talks himself. “Richie was a one-man band for negotiating contracts,” he said. Melius worked hard to burnish his image and cultivate connections to Long Island’s elite. He joined the Better Business Bureau and supported charities, such as the Nassau Children’s House, winning a “Friend of the Youth” award. He listened in his car to tapes of the Rolling Stones and the “The Bodyguard” soundtrack, according to court records. But he found his way to the board of the Long Island Philharmonic, joining On its face, nothing seems drier than the minutiae of a labor contract, particularly one involving police work. Yet it was over obscure issues like accrued time off, night differential and shift rotation that epic confrontations took place years ago, leading to staggering boosts in police pay and benefits that saddle Long Island taxpayers to this day. The changes were largely the work of a math genius with an unquenchable gambling obsession, the lawyer Richard Hartman, who was aided by a canny and ambitious town supervisor named Alfonse D’Amato. In 1969, Hartman landed the Nassau Police Benevolent Association as a client and threw himself into contract negotiations, according to the labor lawyer Thomas Lamberti. Hartman proposed not just pay increases, but also significant cuts in the length of the workweek. Then-Nassau County Executive Ralph Caso, a Republican, went along when times were flush. Hartman gave Caso a lot to go along with, like an additional night differential for the 3,500-member force, more overtime and the right to add unused time to pension calculations. As pay and benefits piled up for the county police force, officials of Nassau villages with their own police departments worried — correctly — that their officers would demand parity. Lamberti, who represented those Nassau villages, challenged the county police contract in 1973 in a way that turned it into a national issue. He filed a complaint with the federal Cost of Living Council, an agency created by President Richard Nixon in 1971 to slow inflation. Lamberti argued that when the cost of benefits was added to the 7.5 percent wage hikes agreed to by Nassau, the contract really amounted to a 15 percent raise. The council agreed, ordering the county in January 1974 to cut the raise to 5.5 percent. The following spring, Hartman asked the U.S. Supreme Court to stay the order, but it refused. The two sides settled. Nassau agreed to pay a $220,000 fine for violating wage controls, and the federal government agreed to the 7.5 percent pay raise, Lamberti said. The following year, the battle lines shifted. The county was in a deep recession. Police costs had increased 250 percent since 1970, forcing a near-record property tax hike. Caso broke with the PBA. Negotiations broke down after hundreds of cops called in sick with “blue flu.” An arbitration panel awarded the union a 12.3 percent NEWSDAY / STAN WOLFSON sandra.peddie@newsday.com such members as Louis Fortunoff, then executive vice president of the Fortunoff jewelry and home goods chain; Raymond Jansen, then the publisher and CEO of Newsday; and Steven Sabbeth, then the Nassau Democratic leader and a close friend. Sabbeth later was sentenced to 8 years in federal prison for bankruptcy fraud. Melius became an ample contributor to charity through the foundation he named for his mother, Elena, often avoiding public credit, because, he told Newsday, “then you’re doing it for a different reason.” The “Oheka Cares” website says the Elena Melius Foundation has given away more than $2.8 million to nearly 500 recipients. In one year alone, 2014, the foundation reported raising about $293,000 and giving it all away in grants. The beneficiaries included the Fire Marshal Benevolent Association of Nassau County, which received $1,000; the FBI Agents Association, which received $5,000; and the Pat Cairo Family Foundation, which received $1,000. The Cairo foundation was set up by Joseph Cairo, who is second-incommand in the Nassau Republican Party. As an example of his low-key approach to giving, he recalled that when someone suggested inviting news coverage, he threatened to cancel a reception at Oheka he hosted for the divers who looked for bodies after the Flight 800 crash that killed 230 people off East Moriches in 1996. “I said, ‘No, then you’re not coming. I don’t want any publicity for it.’ ” Richard Amper, executive director of the Long Island Pine Barrens Society, said Melius has given $72,500 since 2007, either by direct donations or reducing the rate for the group’s annual fundraiser at Oheka. “I would say that he makes distinctions between people who can afford an expensive wedding and people trying to do the public good,” Amper said. His good works also spread his name and helped him develop relationships. “He enjoyed putting people together,” Nassau Democratic leader Jay Jacobs observed. “To him early on, I believe it was about wanting to be connected.” Ryan, of the Association for a Better Long Island, saw much the same thing: “He has this affinity to latch onto people who have access to power.” A life-altering purchase Nothing loomed larger in these efforts than Oheka Castle, where he made his life-changing acquisition, buying the derelict estate in 1984. Helping him was a vibrant woman named Allegra Capra. She was the former longtime girlfriend of Carmine “The Snake” Persico, boss of the Colombo crime family after its war with “Crazy Joe” Gallo and his brothers. Capra ran North Site Realty of Syosset, which was financed by her later companion, Sam Scibelli, a Westbury auto shop owner. Scibelli, asked if he himself had organized crime ties, said, “There was no gangsters involved.” According to Scibelli and Capra’s HOWARD SCHNAPP NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B16 State Supreme Court Justice Jack Libert in January 2016. niece, Denise Rosner, Capra acted as the broker when Melius bought Oheka for about $1.5 million, with a $2 million mortgage from Ditkowich. Local newspapers reported the purchase with photos showing Melius beaming with pride. A notation on the Oheka deed directs that it be sent to “Gary Melius, Esq.,” even though Melius’ formal education ended in the eighth grade. Otto Hermann Kahn, a Germanborn financial adviser to the Rockefellers, constructed Oheka, an acronym of his name, in Huntington as an opulent getaway that surpassed all Gold Coast mansions. The estate included reflecting pools, stables, an 18-hole golf course and an airstrip, and for decades it was the secondlargest private residence in America, appearing as Xanadu in Orson Welles’ film “Citizen Kane.” After Kahn’s death, his widow, Addie, sold the castle and it fell into a disrepair that culminated when the Eastern Military Academy, which had Three decades of Melius Foundation philanthropy BY KEITH HERBERT AND WILL VAN SANT NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com keith.herbert@newsday.com will.vansant@newsday.com The Elena Melius Foundation has donated more than $2.8 million to nearly 500 charities or individuals over the last three decades, according to the Oheka Castle website and filings with state regulators. Recipients have included well-known health care organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association; Catholic Charities, the American Jewish Committee and other religiously affiliated groups; and law enforcement organizations like the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund. “I never promote what I give away,” Gary Melius said in a conversation with Newsday editors last April. A section of the Oheka website called “Oheka Cares” lists more than 480 recipients of donations since 1986. The donations were made through the foundation, named after Melius’ late mother and headquartered at Oheka. On average, the foundation donated $153,000 annually between 2006 and 2015, or more than $1.5 million altogether, according to state records. Melius said recent financial difficulties had not stopped him from giving his money away. “I am broke now,” Melius said in the Newsday interview. “I still borrow money to give to charity.” While many of the recipients of Melius’ generosity are Long Island charities, organizations in New York State and beyond are also recipients of money from the Melius Foundation, state records show. In 2014, for example, the foundation’s grants and contributions included $15,500 to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City; $15,000 to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota; $10,000 to the Family & Children’s Association of Mineola; $6,000 to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor; and $6,000 to St. Christopher’s Inn, a shelter and treatment center for homeless men in upstate Garrison. Charitable groups created by politicians with whom Melius has been allied have also received donations from his foundation. Among these are the Pat Cairo Family Foundation, created by Joseph Cairo, a Republican Party leader from North Valley Stream, in honor of his wife, Pat, to support cancer patients; and the Marie Cuthbertson Scholarship Fund, named for the mother of Huntington Town Councilman Mark Cuthbertson. The Family & Children’s Association, based in Mineola, provides assistance to Long Island’s most vulnerable children, families and seniors. Patricia Pryor-Bonica, a board member of the association, said she believes that Melius shares her concern that struggling families should be helped — and that, like her, his willingness to help was rooted in his own experiences in tougher times. “There was no help back in those made the castle its home, went bankrupt in 1979. The property was abandoned, and vandals left it in ruins. Melius’ decision to purchase and renovate Oheka was a risk more experienced developers bypassed. “That’s the gambler,” his friend John Nasseff said. “He takes chances. Your average businessman, before making a big purchase, consults with a CPA and an attorney. Gary acts right away.” Melius continued buying properties. In 1986, he successfully bid $1.4 million for a shuttered pumping station in Freeport called the Brooklyn Water Works. He had hoped to convert the 19th-century Romanesque Revival structure with castle-like towers and arching windows into a condominium development, although years of trouble awaited. Two years later, he entered the fortunate club of developers who secured bargain leases at Mitchel Field. Melius paid $7.6 million to take over the lease at 107 Charles Lindbergh Blvd. from the warehouse of Webcor, a troubled manufacturing company, records show. Under the leases, the county had no authority to renegotiate terms upon a sale. The omission of what is called a non-assignability clause, considered standard business practice, cost the county millions in lost revenue. But it was a developer’s windfall. “I only paid those kind of dollars because of the lease terms,” Melius told Newsday at the time. “It’s a good deal for the buyer.” His lawyers were Libert, a member of Armand days,” said Bonica, recalling her youth in the 1940s and ’50s. The Elena Melius Foundation has experienced controversy at times. In 2002, it purchased a 98-acre parcel for $50,000 on the Akwesasne Indian reservation near the Canadian border, where Melius had been involved in the tumultuous construction of a tribal casino. A year later, the foundation tried to sell the land for $300,000, according to court records. Because the transactions involved the foundation, the sale could not be completed without the approval of the state attorney general’s office, which regulates charitable groups. The attorney general objected, saying that a $50,000 “finder’s fee” for Melius that was part of the sale represented “self-dealing” by Melius, a director of the nonprofit. Melius tried two more times to obtain the state’s approval for the sale, this time including a $25,000 fee to a Melius employee, Rich Hamelin, according to court records. The attorney general’s office continued to object, saying that the fee was “an improvident use of charitable B17 Gary Melius in the dining room of Oheka Castle in February 1989. He bought the derelict estate in 1984. NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 NEWSDAY / DAVID L. POKRESS newsday.com assets.” Finally, Melius went to court, where State Supreme Court Justice Geoffrey J. O’Connell approved the sale and the fee in 2007. In his ruling, O’Connell cited “the apparently undisputed large profit to the foundation, which will assist it greatly in carrying out its charitable purposes.” In another instance, Melius said last year that the state attorney general’s office had issued subpoenas to him and his foundation, requesting documents. Newsday reported that the subpoenas related to the foundation’s acceptance of $250,000 from another foundation that one of his friends, Steven Schlesinger, then counsel to the Nassau Democratic Party, had been appointed by the courts to manage. Melius’ statement came in an application to Nassau County for a sewer connection to Oheka Castle that would handle wastewater from a related proposal to build 191 condominium units. Melius has strongly denied any wrongdoing. NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION D’Amato’s law firm, and Joseph Carlino, the former Assembly speaker, who was of counsel to the law firm. The broker who worked with Melius was Samuel A. Rozzi, the nephew of then-Police Commissioner Samuel Rozzi and Santa Rozzi, who was chief of the county’s bureau of real estate and insurance. The broker did not respond to a request for comment. Asked at the time about his use of politically connected lawyers, Melius was incredulous. “Who would you go to — a nonpolitical lawyer?” he asked rhetorically. “Let’s be realistic.” But it wasn’t long before Melius ran into trouble. The economy, and the real estate market along with it, was soon in crisis and office vacancies on Long Island topped 15 percent. The building on Lindbergh Boulevard remained empty. But in a remarkable turn of fortune, the Internal Revenue Service agreed in October 1989 to rent the building for a decade for $1.7 million a year, according to court records. At the time, D’Amato was on the Senate committee overseeing the IRS. In contrast to his pragmatic comment about hiring politically connected lawyers like Libert, when the deal was announced, Melius said his connections had played “zero” role in landing the deal. But it opened a few eyes in Long Island’s real estate community. Ryan, the longtime director of the industry’s trade association, recently observed, “You do not get institutional tenants like that without some kind of influence from somebody. That just doesn’t happen.” NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B18 CHAPTER 3 CASINO FLOP: STRUGGLING OUTSIDE LI’S COZY NETWORK BY KEITH HERBERT AND GUS GARCIA-ROBERTS keith.herbert@newsday.com NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com G ary Melius has been rooted in Long Island in almost every way. He grew up in a modest tract house in West Hempstead and lives in a castle in Huntington. He was mixed up early in criminal activity in Nassau County but came to befriend police leaders in both counties, as well as FBI agents and cops from many local departments. He became a multimillionaire here, has easily given more than $4 million to scores of local charities and politicians himself and with his family members, businesses, employees and foundation, and became a friend of judges, mayors and county executives. Yet, in the mid-’90s, he could be found scrambling on an often icedover Indian reservation a 400-mile drive away, clinging to the dream of Akwesasne N.Y. making millions through a tribal casino as he faced challenges from federal regulators, a canny gaming mogul and Mohawks who felt deceived by him. His quest was the culmination of a decade of bankruptcy and a panorama of business misfortunes. Those ventures often occurred when he was distanced from his Long Island political network. When Melius operated on the political playing fields of Long Island, he most often thrived. Off them, he usually fumbled, begging the question: What accounts for the difference? For Melius, the decade included five business-related bankruptcies; more than $20 million in debt to creditors who had to settle for as little as 5 cents on the dollar; hundreds of thousands of dollars in unpaid gambling bills, mostly at Donald Trump’s casinos; an investigation by a federal commission that The windswept Indian reservation called Akwesasne is home to the St. Regis Mohawk tribe. A 400-mile drive north of Long Island, the reservation straddles the New YorkCanada border. The 28,000-acre reservation encompasses parts of towns in both countries with a main blacktop road as a spine that is dotted by discount smoke shops and cheap gas stations. forced him to sell his 50 percent share in a company seeking to run a casino on an upstate Indian reservation; and an accusation by a major bank that he was fronting for organized crime figures. A string of bankruptcies His real estate meltdowns stemmed in good part from the 1986 tax reforms signed by President Ronald Reagan. With the elimination of tax shelters that propped up commercial real estate, Long Island’s property market skidded just as the stock market experienced a historic crash. At one point, Melius said in an interview, he was “rolling quarters” just to pay bills. The bankruptcies enveloped many of his greatest successes, starting with his first at 300 Old Country Rd. in Mineola, where he had run a small contracting company in a run-down building owned by his lawyer and mentor, Richard Hartman. Melius bought the place, replaced it with a commercial condo complex, and put units on the market at prices that would have had the potential to yield about $17 million. Then, in 1990, he was seeking protection from a $7.1 million foreclosure on the property. The bankruptcies also covered properties in Uniondale, Carle Place and Lemont, Illinois, outside Chicago, voluminous bankruptcy records show. Among the casinos chasing Melius for more than $250,000 were Atlantic City’s Trump Plaza Hotel, Trump Taj Mahal Casino, the Showboat Casino and another in the Bahamas, according to an investigative memorandum by the staff of the National Indian Gaming Commission. The Bank of New York, which was trying to recoup money from Melius on a troubled mortgage, said it had looked into his assets and then accused him of being involved with members of organized crime. Melius’ lawyer adamantly denied the allegation. Melius’ early criminal record included a bust for stealing Cadillacs for an organized crime ring, according to court testimony. Assertions and, in some cases, B19 NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION NEWSDAY / JOHN PARASKEVAS Casino flop: Struggling outside LI’s cozy network The upstate Akwesasne Mohawk Casino Resort in October 2016. to Gabriela Cacuci, a lawyer representing the bank who is now a senior New York City corporation counsel. In his complaint filed in 1996, Melius’ lawyer, Richard Lane, wrote that Cacuci met with him and said that the bank had obtained information that accused his client of “fronting for the Gambino crime family.” The court documents do not provide details of the allegation. Lane’s complaint contends that Cacuci said Melius was “allegedly connected” with several unnamed organized crime figures who were still alive and two notorious mobsters who were dead — Roy DeMeo and Tommy Agro. The complaint did not specify how. Before being murdered in 1983, DeMeo was widely regarded as a vicious killer, with a reputation for dismembering victims behind a Brooklyn bar he owned called The Gemini. In his definitive mob history “Five Families,” the author Selwyn Raab described DeMeo as the Gambino family’s “most feared hitman,” according to federal and city authorities. Agro was a bookmaker and violent Gambino soldier who eventually pleaded guilty to extortion and loan sharking. In a Newsday interview, Melius was asked directly about the allegations in the lawsuit. Denying any mob CONTINUES on B20 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 turned government witness, alleged that Mafia figures “had contact” with D’Amato, according to an internal 1992 FBI memo. The memo said D’Arco named five individuals, including Phil Basile, who owned the Island Park club where D’Amato celebrated his 1980 Senate victory, but did not specify how often the contacts purportedly took place or over what. These assertions did not lead to any charges against D’Amato, who over the years has adamantly denied any association with the mob. Melius faced similar allegations. They came to light through his own doing, after he defaulted on a $1.8 million loan involving a building on West 58th Street in Manhattan. The job of recovering the loan fell newsday.com instances of mob involvement by politicians and real estate operators have laced a half-century of Long Island history. Among the controversies confronted by Melius’ great ally, Alfonse D’Amato, were several involving organized crime figures. As a U.S. senator, he unsuccessfully sought favorable treatment from federal prosecutors for Paul Castellano, boss of the Gambino crime family, and Mario Gigante, the brother of the boss of the Genovese crime family, Vincent “Chin” Gigante. D’Amato insisted he was simply providing the same constituent service he would for any New Yorker. Alphonso D’Arco, former boss of the Lucchese crime family who NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com involvement, he said, “I don’t know where that comes from.” In court papers, Lane called the assertions “malicious” and “without merit.” Melius said in his lawsuit that the bank had threatened that if he did not pay up, it would lay out the allegations during court proceedings, which would have made them public. At one point, Cacuci said in an interview, she received a phone call at her office from a man who identified himself only as “Gary’s lieutenant.” He warned her to leave Melius alone. “The message was clear,” she said. “Stop pushing. Stop looking for assets.” A settlement with the bank required him to pay $510,000 to satisfy the debt, and in return the bank agreed to keep confidential its findings “regarding Melius’ assets, sources of cash flow and business dealings and associates,” according to court documents. That closed the chapter until the lid of confidentiality was lifted by Melius himself, when he filed a multimillion-dollar suit against the bank after being annoyed by erroneous past-due notices he received after the settlement. In delineating the hardship he said he faced, Melius listed what he said the bank had asserted about his relationship with the Gambinos. That put it in the court record, unnoticed for two decades until discovered by Newsday. Melius said in an interview that he did not remember anything about his dispute with the bank. But he explained why he would retaliate against the bank, even if it meant outing allegations against him. “If you mess with me, I will sue you,” Melius said. The case ended by mutual agreement in 1997, soon after a judge dismissed all but one of Melius’ claims, court records show. The bank wasn’t alone in drawing Melius’ ire. In more than 225 state and federal lawsuits over the years, he revealed himself at times to be impetuous and belligerent. He sued his dry cleaner over $700 he said he left in his pants pocket (an arbitrator ruled that Melius couldn’t prove that someone had removed the cash from his pants). He interrupted a deposition over a leased Mercedes to call a car salesman a “turd” and a “low life.” In the deposition, the salesman described a phone call from Melius this way: “more abuse, more foul language, more threatening me and my boss.” In another lawsuit years later, Melius confronted Matthew Dollinger, an attorney for the developer Wilbur Breslin. “You think you are a tough guy, Matthew?” Melius said during a deposition. “You are not a tough guy.” Melius then used a gay slur, adding, “How’s that for an insult? A fat one.” To those who know him — even what successful sexploitation epic “Flesh Gordon.” Even Playboy hated it. More to the point, Allegro said in an interview, “We certainly didn’t make any money on it.” A new focus: tribal gambling ASSOCIATED PRESS / MARIO SURIANI NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B20 friends — Melius’ abrasiveness is no surprise. “I figured he’s got a lot of friends, but he’s got a lot of enemies,” said an old friend, John Nasseff, a former executive and major stockholder of West, the legal publishing company. “He sticks his nose in everything and he steps on a couple of toes.” Then, cryptically and without elaboration, he added: “And that’s why they’ve tried to do him in a couple of times.” Various partners, ventures Melius had a penchant for linking up with questionable business partners, often in quixotic ventures. Rather than team with Hartman and other insiders as he had on previous real estate ventures, he went outside the loop for a partner on two deals at Mitchel Field, where Nassau County leased properties to politically connected developers in giveaway deals. His partner, Greg Hasho, was a branch manager for an out-of-control penny stock brokerage referred to in Newsday as “The Wild Bunch” and was married to the niece of Times Square porn czar Matthew “Matty the Horse” Ianniello, who later became acting boss of the Genovese crime family. The partnership faltered after the federal Securities and Exchange Commission accused the brokerage of bilking clients of $1.4 million. In the aftermath, Hasho declared bankruptcy and his partnership with Melius faltered. Three years later, the SEC barred Hasho from any management or ownership role with a securities firm. Melius worked, too, with Paolo Gucci, who had been banished from the famous luxury brand family after he helped send his father to prison for tax evasion. Melius’ hopes of helping him build his own fashion brand ended when Gucci, who was jailed for failing to pay Michael Olajide, left, takes on Knox Brown in a middleweight bout in 1986. child support and alimony, died bankrupt in 1995. Chet Forte, the original director of “Monday Night Football,” was another star-crossed partner. Melius was among several investors in a proposed basketball TV show to be produced by Forte that collapsed. According to a court filing, when television producers Peter Perrotta and Louis LaRose Jr. arrived at Oheka for a meeting on the project, they were met by men armed with guns and accompanied by pit bull guard dogs. They said they were surprised to find Melius in a poker game with Forte, who, it turned out, was a ruinously compulsive gambler. Melius won back his $130,000 investment from Forte in court. Melius also tried his hand at boxing management, joining with a former nightclub singer, Joe Allegro, to manage a trio that included Trevor Berbick, who years earlier had defeated Muhammad Ali in Ali’s last fight. They set up another of their fighters, Michael Olajide, a middleweight with a chronic vision problem in his right eye, in a super middleweight championship bout against Tommy “Hitman” Hearns, the champion who was known as pound-forpound the hardest puncher in the sport. “I remember that first really hard jab that he threw — bam!” Olajide said in an interview. “He hit me in the eye, and I just remember at that point not being able to see anything coming from one side.” After losing the fight, he spent more than a year fighting in court with Melius and his partner for his share of the purse before he was paid, court records show. And then there was an investment Melius and his partner, Allegro, made in “Flesh Gordon Meets the Cosmic Cheerleaders,” a sequel to the some- By Melius’ own admission, an awful lot wasn’t going his way in the ’90s. “I think other than real estate, and I have a whole list of things that I lost my money in, every single one of them,” he said in a Newsday interview. So he headed north, to the desolate upstate Akwesasne Indian reservation spanning the Canadian border, where, far from any city with a substantial customer base, he saw promise in tribal gambling. The reservation is home to the St. Regis Mohawks and has a fraught history marked both by illicit trafficking in cigarettes, liquor and arms, and divisions over gambling so intense that two tribe members were killed in a gunfight. “The real estate market has gone bad,” Melius explained to a Syracuse reporter in October 1995. “I had my trouble in it. Let me see if there’s opportunity here.” Melius became interested in gambling on Native American reservations around the time Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988, providing a legal framework for tribal casinos. At Oheka the effects were visible. Local power brokers were joined by a new set that included Michael Haney, a leader of the American Indian Movement that besieged Wounded Knee; William Kunstler, the famed left-wing attorney who represented both tribes and individual Native Americans; and Moonface Bear, who would lead Connecticut’s Golden Hill Paugussetts in an armed uprising in the early 1990s. Melius formed companies with names like Native American Management Corp. and Nassau County Native Americans Inc., founded to “promote Native American development and secure their historical lands,” according to planning documents reviewed by Newsday. According to business documents and Native Americans who said he discussed his plans with them, Melius was unsuccessful in efforts to develop casinos or otherwise do business with the Shinnecock on Long Island, the Seminole in Florida, the Kickapoo in Oklahoma and the Schaghticoke in Connecticut. He was involved in failed efforts to get recognition for tiny tribes, including the Poospatuck, then consisting of 95 people living near Mastic. But he arrived at windswept Akwesasne with scant competition and the financial muscle and respectability of his partner, Ivan Kaufman, head of the publicly traded Arbor Commercial Mortgage Trust, who has lent B21 NICK CARDILLICCHIO Seeking a tribal pact Anthony Laughing in the mid-1990s. killer, explained in an interview: “The Gambinos was going to make good money with the father. They’re telling me that we’re going to do whatever to help the kid because we want the father.” Borrello said he knew nothing about any designs the Gambinos might have had in a casino involving him. “I work seven days a week, I don’t really know nobody, they murdered my son, and I’m not on the street,” he said in an interview. Melius would pay him at least $580,000 over the next six years, according to records filed in federal court, and Borrello recalled receiving other perks, too. He said they included a private plane trip to CONTINUES on B22 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 bino family as a conduit to the tribal casino business — exactly what Melius hired him to be. Nicknamed “Mohawk John,” Borrello had done time for burglarizing a gas station and fencing stolen cars in the mid- to late 1980s. By his account and those in court and law enforcement records, his son, “Johnnie Boy” Borrello, was a Gambino crime family associate murdered in a mob rubout. According to Michael “Mikey Scars” DiLeonardo, a former Gambino capo, and John Alite, a former mob associate, who have both become federal witnesses, the Gambinos had tried to protect the younger Borrello to cultivate his father. Alite, who was convicted of attempting to murder Johnnie Boy’s newsday.com Melius more than $50 million over the years through his privately held companies. The two formed President R.C.-St. Regis Management Co., based in Arbor’s Uniondale offices, and sought authorization from the Mohawks to build and operate the reservation’s first legal casino in exchange for a percentage of the profits. A confident Melius told tribe members that the casino would employ 800 people and Kaufman predicted annual revenues of $100 million. To succeed, the company had to win over the tribe’s troika of chiefs. Here, Melius hired a “consultant” named John Borrello, an ex-convict from Queens who was half-Mohawk, and who two former mobsters told Newsday was coveted by the Gam- Valerie Curotte, Borrello’s cousin, said that during an early meeting about the casino, at Melius’ Long Island office, Melius discussed with her the plans he and Borrello were making. Melius stressed that his associate’s role had to be kept quiet. “He says to John, ‘You’ve got a record longer than my arm,’ ” Curotte recalled in an interview. “You can’t really be on no paperwork.” Borrello also introduced Melius to another cousin, Anthony Laughing, described in court documents and by his own account as the boss of all things political and criminal on the reservation. Laughing made millions smuggling cigarettes to Canada, according to court records and by his own admission. He poured the profits into what he has said was Akwesasne’s first full-scale — albeit illegal — casino in 1988, Tony’s Vegas International. Convicted on federal gambling charges, he spent time in prison and, according to an FBI surveillance report, returned to the cavernous casino in gold and diamond jewelry and alligator boots while federal agents conducted surveillance. “He was the Godfather up there,” said retired FBI agent John McEligot, who spent years investigating Laughing. “He was his own mafia on the reservation.” In an interview with Newsday shortly before his death at 69 in October 2016, Laughing recalled Melius hosting him at Oheka, plying him with fancy dinners and Knicks playoffs tickets, and introducing him to D’Amato at a Long Island law office. The reason was obvious to him: Three chiefs decided practically everything on the reservation by majority, and Laughing said two, L. David Jacobs and John Loran, answered to him. “I don’t know how to say this but I’ll just come right out and say it,” Laughing said. “I controlled the two chiefs back then.” Ever affable and energetic, Melius worked a rotating cast of chiefs, who faced election every three years. “He was a busy little fella,” said Jacobs, who visited Melius at Oheka. “He certainly was very generous, loaning his airplane to everybody and giving everybody dinners.” In the end, Jacobs and Loran — the chiefs Laughing claimed to control — outvoted their counterpart, Phil Tarbell, and pushed through a tribal compact giving Melius and Kaufman’s company management rights. Jacobs and Loran insisted in interviews that NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION Akwesasne on which he played poker with Melius, Paolo Gucci and D’Amato, who was dropped off en route for what Borrello described as a “meeting with the power authority.” B22 they had acted on their own and were not beholden to Laughing. NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION Gaming commission investigates Now, another challenge loomed: approval of a contract to manage the casino from the National Indian Gaming Commission, the federal agency established by Congress to keep “organized crime and other corrupting influences” from the nascent industry. Melius submitted more than 200 supporting letters from police chiefs, politicians, clergymen and even former President Jimmy Carter, according to a court document his attorney filed. Besides Carter, the document did not name the other supporters and the commission refused to provide Newsday the letters. But they were overshadowed by the commission’s staff investigation, summed up in a 20-page memorandum completed in May 1996. It recommended that Melius be found unfit for casino management, determining that his “reputation, habits and associations pose a threat to the public interest or to the effective regulation and control of gaming.” The memorandum cited his repeated failure to provide detailed financial information regarding his casino-related companies, as well as inconsistencies between his and his wife’s income declarations. In addition, his $29 million estimate of personal assets, investigators determined, was largely based on his valuation of a bankrupt company; under a reorganization plan, they said, unsecured creditors were to receive 5 percent of their claims. In a compilation of his financial and criminal problems, it detailed 15 state tax liens totaling almost $470,000, as well as an IRS lien of nearly $200,000 that remained unsatisfied until the commission investigation began. The memorandum cited five corporate bankruptcies. The gaming commission investigators also noted that among dozens of judgments against Melius, several stemmed from debts to casinos. Then there was his early criminal record. The memorandum listed five arrests on a federal background check, including his vacated felony conviction: In June 1962, Melius was charged with petty larceny in a case involving the theft of tires with a teenage friend. There is no record of the disposition. In June 1963, he was charged with robbery in the mugging of a hitchhiker and pleaded guilty a half-year later to felony attempted second-degree grand larceny and was given a suspended prison sentence of up to 5 years. Six years later, while on probation, Melius’ conviction was vacated under a youthful offender law. On Sept. 14, 1971, he was charged with grand larceny in the extortion of an undercover cop who posed as having illegal drugs in her car. He pleaded guilty and was later sentenced to 3 years of probation and fined $1,000. On Sept. 30, 1971, he was charged with third-degree conspiracy and first-degree criminal possession of stolen property for his alleged role in a car and heavy equipment theft ring. Melius pleaded guilty to third-degree conspiracy and was fined $500. In October 1971, he was arrested for second-degree grand larceny for unknown reasons and the charge was dismissed. In a letter to a tribal chief a few months after receipt of the memorandum, commission chairman Harold Monteau stated that the contract to manage the casino would not be approved unless Melius was removed from the management group. Monteau also said that the management contract would not be approved if Melius were engaged as a consultant. After papers were drawn showing Melius selling his interest to Kaufman for $5 million, the commission approved the company’s contract with the tribe. Kaufman declined to be interviewed. Melius maintains a role Although the chairman’s decision might have marked an end to Melius’ reservation foray, it did not. He never left the Akwesasne reservation. Kaufman awarded a $14 million contract to build the casino to the Anderson-Blake Construction Corp. Melius owned the company. The tribe contended in a 2002 lawsuit that Kaufman had failed to get the gaming commission’s approval for Melius to build the casino. The Mohawks were seeking to have the construction contract voided. Kaufman and Melius responded that tribal leaders had clearly been aware of Melius’ role in constructing the casino. They also said in legal filings that Kaufman had not been required to get permission from the Indian gaming commission to award the contract to Melius’ company — a position that was eventually confirmed by the commission’s top lawyer, who stated in a letter in 2004 that the construction contract had not required the commission chairman’s approval. The Mohawks also argued in their lawsuit that Melius had been enmeshed in many details of the casino’s operation. They produced documents showing that Melius was often consulted on the casino’s operations by President-R.C. St. Regis executives and that a former state trooper was his personal eyes and ears. Records showed that Melius had exchanged memos and faxes with consultants and Arbor employees about marketing strategy, security, budget and other casino matters. Walter Horn, an Arbor attorney who served as St. Regis’ general counsel and senior vice president, asked Melius for comment on a loan document between the tribe and President, for example. Horn also faxed Melius internal memos about casino marketing. John Natalone, an Arbor executive, sent Melius financial forecasts. In an October 1998 letter filed in court, Melius sent congratulations to Al Crary, a retired State Police captain, writing that when the casino opened, “you will be hired as their Security Consultant at a salary of $50,000 per year.” Other records show that Crary sent Melius notes marked “FOR GARY EYES ONLY,” on topics ranging from observations about the ATM dollar limits to well-sourced intelligence. “The Indians north of the border are well armed and the Mohawks are the strongest of the lot,” he wrote in an undated memo. “My informants tell me of no discernible pattern of action against the casino,” although he added that he was concerned “that you do everything you can in a defensive mode.” In an interview, Crary said he had not been hired by Melius or anyone else at the casino. Of Melius, he said, he would “just try to fill him in on what was going on.” Melius did not dispute his ownership of the construction company but said in interviews and depositions that he had not been involved in either managing the casino or working as a consultant, which the gaming commission had also made clear it would not approve him to do. “I was never involved with the day-to-day running of the operation,” he said in a 2014 Newsday interview. A federal judge ultimately dismissed the tribe’s lawsuit, ruling that Kaufman had not been required to get permission from the gaming commission to hire Melius’ construction company. Federal oversight over a casino on an Indian reservation only involves its management, the judge said. It was the only issue before him. The tribe’s lawsuit was one of several over Melius’ interactions with the tribe and the gaming commission, including a suit filed by Kaufman and Melius against the Mohawks. Melius B23 had sunk about $30 million into Akwesasne and received “a zero return,” Horn, the casino company’s senior vice president, testified. NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION NEWSDAY / J. MICHAEL DOMBROSKI Donald Trump inside Atlantic City’s Trump Taj Mahal Casino in March 1990. ment from the tribe. Part of the Akwesasne water supply was rendered undrinkable for an extended period because, the tribe alleged, a construction mistake by a Melius subcontractor polluted it with salt water. They reached a $500,000 settlement with Melius’ company and the subcontractor, neither of which acknowledged blame. But, validating Thompson’s and Ransom’s belief that the operation could make money, the Akwesasne casino remains open and it turns a profit, thanks to a clientele that largely includes Mohawks and seniors arriving by bus from nearby places like Plattsburgh. After mountains of litigation, Melius won a $4 million settlement from Goldberg’s company in 2002. Neither side admitted any wrongdoing. By the late 1990s, his evolution into a Long Island power broker was materializing through a chain of events at Oheka Castle, where, as at Akwesasne, he was involved with legally entangled associates and ran afoul of neighbors. Some of his business associates there were at least as questionable as some of those at Akwesasne. The official orders and rules he dodged were far more plentiful than those at the reservation. And he had neighbors who battled him every bit as much as the Mohawks had. But Oheka was on his home turf, and he came out a winner. NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 If someone were to buy out Melius’ share in the company, Monteau indicated, he would be open to moving forward, provided that Melius retained no financial interest in the management. The casino opened in 1999, an instant financial flop. The mostly tribal staff was slashed. After a year, former Chief Alma Ransom said in a deposition, Kaufman told her losses sometimes reached $1 million a month. Kaufman’s relationship with the Mohawks nose-dived. Tribal leaders accused him and his management team of hiring untrained and uncertified staff at the casino, providing inaccurate revenue reporting and offering jackpots that were awarded by mistake. “They knew nothing about how to run a casino, and that’s why they were running into the problems,” then-Chief Paul Thompson remarked in a 2002 deposition. By early 2000, Kaufman and others Former St. Regis Mohawk chief L. David Jacobs in October 2016. newsday.com also sued the commission at one point over the information in the staff’s memorandum, the one that recommended he be found unfit to manage the Akwesasne casino. Melius’ suit was eventually dismissed, though it is not clear whether there was a settlement. But in a letter to Melius in June 2001, Montie Deer, who was then chairman of the commission, said the agency had “never made a determination of your suitability to participate in a management contract” to operate the Akwesasne casino. The commission, Deer wrote, “has not taken action approving or disapproving a management contract to which you were a party.” That was accurate, though the context was not explained in the letter. Harold Monteau, who was the commission chairman in 1996, wrote a letter in which he said he would disapprove the tribe’s proposed contract with the company created by Melius and Kaufman because of the commission’s concerns about Melius’ suitability to manage a casino. The stories of Gary Melius’ life seldom end simply. This one certainly didn’t. It even featured a cameo by Trump. For help, Melius turned to D’Amato, who introduced him to the country’s most successful casino operator, a high-rolling New Jersey businessman named Arthur Goldberg. Goldberg had little use for the Akwesasne operation, but he wanted to team with the tribe on another plan it was involved in: a half-billion-dollar proposal in the Catskills for the closest casino to New York City. With a supporting affidavit from D’Amato, Melius said in a lawsuit that Goldberg had offered to pay him $15 million and bail out Kaufman if they persuaded the Mohawks to install his company as their new manager at Akwesasne and open the way to a Catskills partnership. But as Kaufman and Melius went to work, court records establish, they were being played. Tribal leaders testified that Goldberg told them Melius had deceived federal authorities about his continued project involvement, cheated on construction costs, siphoned away money that should have been paid to contractors, and bragged about having the tribal council in his pocket. “We were being burnt big time, and we found out this place can make money,” Ransom, then a chief, recalled in a deposition. Before long, the tribe threw out Kaufman’s management company and teamed in the Catskills with Goldberg, who did not pay Melius or Kaufman a dime. There the Mohawks ran into Trump, who feared their plan would damage his Atlantic City businesses. Soon local newspaper ads attributed to an anti-gambling group in upstate Rome cautioned, “How much do you really know about the St. Regis Mohawk Indians?” Another ad predicted Indian gambling would bring “increased crime, broken families, bankruptcies, and, in the case of the Mohawks, violence.” In the end, nobody fared too well. Goldberg died unexpectedly and his Catskills casino was never built. A state investigation found that Trump had secretly financed the newspaper ads and he was fined $250,000 in 2000 for violating lobbying laws. More critically, his Atlantic City casinos went bankrupt over the next decade, even without Catskills competition. The two chiefs who originally backed Kaufman and Melius’ management were convicted on unrelated charges stemming from huge illicit smuggling operations. The one who didn’t was convicted of stealing equip- NEWSDAY / JOHN PARASKEVAS A Catskills venture NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B24 CHAPTER 4 THE RISE OF OHEKA CASTLE BY SANDRA PEDDIE sandra.peddie@newsday.com NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com C hristopher Okada still remembers the mysterious call his father, Naomi, a New York City real estate broker, received from Japan. “All that my dad knew was that this client was extremely wealthy and he wanted castles,” Okada’s son, Christopher, recalled. “So my dad scouted the tristate area, and there’s not a lot of castles in the tristate area.” But on the Gold Coast of Long Island there was Oheka Castle, and Gary Melius owned it. He had bought the abandoned mansion in 1984 for about $1.5 million, assuming ownership of what had been the grandest of Gold Coast estates and the second-largest residence in America. And he went to work, pouring money into a meticulous restoration he hoped would not only prove worthwhile on its own, but also would open the way for the lucrative development of 39 luxury condos. His condo plan collapsed a few years later, though, along with the real estate and stock markets. His real estate empire was crumbling. He turned his attention to trying to transform the castle into a destination, a place for weddings, parties and other events. Christopher Okada remembered that in 1988 his father called Melius on behalf of his new Japanese client. It was the sort of moment people hope for when they buy lottery tickets. Melius would soon sell Oheka for a recorded price that was 15 times higher than what he bought it for — and get to live there as caretaker to boot. The conversation led to a deal that eventually helped Melius emerge from multiple bankruptcies and business setbacks and enshrined him as a major player in Long Island’s politics and social life. Remarkable in itself, the transformation provides a lens into the workings of Long Island politics and shows how somebody who had nurtured powerful people could overcome a formidable array of obstacles to get what he needed. In Melius’ case, the obstacles included half a million dollars in unpaid property taxes, 17 building and fire code violations, vocal neighbors he had infuriated, business partners who ran afoul of the law, a decisive rejection by the Huntington Town Zoning Board of Appeals and two judicial orders against him, the last of which temporarily shut down Oheka. A billionaire investor Okada’s mysterious client turned out to be one of Japan’s most reviled figures. Hideki Yokoi, an aging billionaire investor connected by the Japanese media with the vicious Yakuza crime syndicate, faced criminal negligence charges after a fire in 1982 ripped through a Tokyo hotel he owned where he hadn’t installed sprinklers. Thirty-three people died. Worried about prison, Yokoi, who denied Yakuza links, wanted to get some of his assets out of Japan, and at one point his family even invested them in a purchase of the Empire State Building, with Donald Trump later joining as a partner. He began buying castles and other luxury residences in Europe and the United States, according to court testimony from a daughter, Kiiko Nakahara. She said that during the 1980s, she took photos of European châteaux and grand estates and sent them to Yokoi for inspection. Through Okada, Yokoi bought Oheka for a recorded price of $22.5 million in 1988. Then in 1993, Yokoi’s son-in-law, Jean-Paul Renoir, who was married to Nakahara, agreed to another deal, in which Melius leased back Oheka for $500,000 a year, records show, which apparently covered property taxes, maintenance and other operating expenses. Violating zoning codes Oheka was zoned residential, ensconced in an exclusive neighborhood near Cold Spring Harbor. Beginning in the early 1990s, Melius defied the zoning and began promoting the castle for weddings and catered events. He hosted private dinners and parties. He used Oheka to impress prospective business partners. He hosted profit-making events like wedding celebrations, a $300-a-seat Debbie Gibson concert and even flea markets. He did this without town permits, a working sprinkler system or fire extinguishers, according to Huntington records. A day after a 1994 “gala evening of tribute” for Frank Grimes, then the Huntington Democratic Party leader, a fire inspector warned Melius in writing to stop using Oheka as “a place of public assembly” until he obtained the required license. Joseph Cassella, who was then Huntington’s chief fire marshal, said in an affidavit that “a potential B25 NEWSDAY / JOHN KEATING Print hed TK catastrophe was barely averted” when children at a bar mitzvah in 1995 were led into a darkened basement for a “Halloween experience.” The basement was decorated with combustible materials that caught fire, then were extinguished, Cassella said. Between 1994 and 1996, inspectors repeatedly found Melius violating zoning restrictions and codes. Records reveal at least 17 citations for illegal wedding receptions, blocked hallways, deadbolts on exit doors, plywood doors where fireproofing was required, combustible debris and unauthorized tree cutting. Lawrence Cregan, who was then town attorney, said he felt compelled to take action against Oheka. “You have to stand for something in this world,” he said in a recent interview. “I have to be able to sleep at night. I have to be able to face my children should something ever come to question. I prefer to do what’s right.” On Oct. 24, 1995, the Huntington Town Board voted to obtain a court order compelling Melius to remedy “dangerous conditions.” Three days later, a judge granted an injunction requiring Melius to comply with fire codes. He was ordered to install emergency lighting and fire stops, rehang fire doors, clear hallways and remove combustible debris. Oheka lacked an operable sprinkler system and so Melius was ordered to install one. He settled the case by agreeing to do so. Tensions were high with neighbors, too, who complained that speakers boomed music so loud their homes rattled. “We do not welcome another summer of lounge lizard music,” a neighbor, Sarah Dunn, wrote to the town in 1996, adding, “the more sleep I lose, the nastier I get.” On top of this, Melius had fallen far behind on property taxes. By 1997, he owed $668,557, tax records show. Melius argued in a deposition that he was in compliance with zoning regulations because he believed there were no restrictions on renting out the residence. The weddings, parties and other events were legal, he insisted, because they were private affairs, including the flea markets and Debbie Gibson concert. For a private residence, though, Oheka was quite busy. During a sixmonth stretch in 1996, 39 weddings and a Sweet 16 party were scheduled, according to documents filed with the court. The town went back to court; in July 1996, another judge, Suffolk Gary Melius at Oheka in October 1995. Supreme Court Justice Howard Berler, found Melius had failed to uphold the earlier “unambiguous” court order. He ordered Oheka shut down until Melius met fire safety codes. In December 1996, a half-year after the court order shutting down Oheka, Melius asked the Huntington Town Zoning Board of Appeals for a variance allowing the castle to be used commercially. He was turned down. A new offensive For owners hoping to win a zoning change, such a record of noncompliance would prove daunting. And Oheka’s circumstances were worse than they looked on the surface. CONTINUES on B26 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com Political lifeline to Huntington Despite his financial struggles in the ’90s, Melius still managed to finance his political lifeline, particularly in Huntington. Considered broadly, between 1985 and 2000, Melius, his family, his companies and employees contributed at least $180,515 to federal, state and local political campaigns, according to campaign finance records. They are incomplete because local campaign records are available only as far back as 2006 and state and federal records go back only to the 1980s. A Gannett Suburban Newspapers survey of corporate contributors that exceeded legal limits found that in 1995, the state’s worst offender was Melius’ Oheka Management Corp., which had exceeded the limits by $21,265. “Who the hell knew anything about this?” Melius said in a Newsday inter- NASSAU COUNTY CLERK Melius was leasing the castle, but its ownership was murky and being contested. The castle was held either by Yokoi, the billionaire who served 2 years in a Japanese prison in the mid-1990s after the calamitous Tokyo hotel fire, or by his daughter, Nakahara, and her husband, Renoir, who had each done prison time during a family battle over Yokoi’s vast real estate holdings in Europe and the United States. After Yokoi filed fraud charges against them in France, Nakahara spent a year in a French jail and Renoir spent more than 2 years in American prisons fighting extradition. The French authorities eventually dropped the extradition request, freeing Renoir — but not before Nakahara was accused by irate mayors in nine French towns of having stripped the castles her father had purchased of marble, statues, tapestries and nearly anything else of value. She was not charged by French authorities. But in Huntington, Melius was playing on his home field and determined to find a way to operate Oheka commercially. What emerged was something new for Melius and far more sophisticated. He fashioned a new offensive that early on included a flash of his traditional aggressiveness — a $10 million libel suit against his most persistent and quotable critic, his neighbor Sarah Dunn, an environmental consultant who filed noise complaints and spoke up at council meetings. But he also paid special attention to his public image, which was honed to portray him as a committed preservationist intent on reclaiming a piece of Long Island history for the public’s benefit. Town board members who had long benefited from his political contributions and friendship would eventually allow commercial use, despite his history of violating town codes and judicial orders, and not paying his taxes. Gary Melius filed a $10 million libel suit against Sarah Dunn, his neighbor who had filed noise complaints. ASSOCIATED PRESS NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B26 Japanese billionaire Hideki Yokoi, seen in New York in 1995, bought Oheka. view at the time. “I called four lawyers, and nobody knew this, so how the heck am I supposed to know? Stupidity they could charge me with. I plead guilty.” Existing records and news articles revealed that over the years Melius, his family members, companies and employees have contributed a substantial part of their combined campaign donations through 2017 — at least $214,067 — to political committees and elected officials from Huntington. In the last dozen years, Melius, his former son-in-law and his companies gave $33,742 to Frank Petrone, according to records. Melius also hosted parties at Oheka for Petrone, who was the Huntington supervisor for 24 years. He did not seek a seventh term last year. Melius became Huntington Councilman Mark Cuthbertson’s biggest donor, giving him at least $31,300, based on campaign records. Steve Israel, a Huntington councilman in 1997 before his election to Congress, received at least $33,200 in donations from Melius and his family for his congressional campaigns. A dominant figure in local Democratic politics as a fundraiser and strategist and a longtime friend of Melius, he held the wedding of a daughter at Oheka in 2013. Israel did not respond to requests for an interview and it’s unknown if the wedding was discounted, a favor Melius frequently offered to friends and political allies. Councilwoman Marlene Budd, who joined the town board in 1996 and married Israel in 2003, became Melius’ lawyer in 1998. She abstained from voting on Oheka matters after that. Budd later became a Family Court judge. A Melius company, ArchCon, designed plans in 2004 for a remodeling project in the Dix Hills home Budd shared with Israel, her then-husband. Melius also held in-kind fundraisers at Oheka — in which services are donated — for Israel and Budd. In addition, since 2005, the Huntington Town Democratic Committee has received at least $25,500 from Melius and his family members. Israel, Budd and Cuthbertson are all Democrats. Petrone changed parties to become a Democrat in 2002. ‘The floating castle district’ Despite this record of support, Melius faced a daunting prospect when he tried once again to legalize the castle’s operations. Residents of Oheka’s quiet upscale neighborhood, still upset by traffic, noise and previous battles with Melius, had mobilized against him. They collected 300 signatures on a petition against his plans and hired an attorney, John Flanagan, currently the Republican majority leader of the State Senate, to fight him. In place of the obstructionism of the past, Melius retained a respected former town attorney and zoning expert, Arthur Goldstein, who aside from his formidable expertise was known for his charm, humor and personal modesty. Goldstein also knew more about the town zoning code than anyone else because he had written it. For Melius, he invented a new zoning category tailor-made for Oheka. It was confined to officially designated historic properties of more than 15 acres. That description fit only Oheka. It was crafted to allow com- Huntington Town Supervisor Frank Petrone with 2008 Miss New York contestants at Oheka in July 2008. mercial use in the name of generating revenue to assist in what was now portrayed as Melius’ singular mission, preservation. Goldstein called the category a “historic overlay district.” In Huntington, as in many areas, there is a firm prohibition against what is known as “spot zoning” — a zoning designation that applies to only one property. While Oheka was the only property affected, the “overlay district” did not directly refer to Oheka. Among town officials it was known as “the floating castle district.” Goldstein launched a charm offensive, meeting with neighbors, and received big support from Ellen Berkowitz Schaffer, an assistant town attorney and a local civic leader, and Joan Cergol, a public relations specialist. Five years later, Cergol became a special assistant to Petrone. In December, she was appointed to the town board. CONTINUES on B28 B27 NEWSDAY / JIM PEPPLER NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION CampaigndonationsbyMelius,familyandhiscompanies BY MATT CLARK matt.clark@newsday.com Candidate or committee contributions ! Nassau County Democratic Party $79,000 ! Freeport Mayor Andrew Hardwick (D) $62,435.93 ! Suffolk County Executive Steve Levy (D) $61,300 ! Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone (D) $53,370.20 ! Rep. Peter King (R) $35,400 ! Hempstead Democratic Party $34,860 ! Huntington Supervisor Frank Petrone (D) $33,742.35 ! Rep. Steve Israel (D) $33,200 ! NewYorkGov.Eliot Spitzer(D)$32,321 ! Huntington Councilman Mark Cuthbertson (D) $31,300 The contributions to Hardwick by Melius, his family and his businesses were primarily for his aborted thirdparty run for Nassau County executive, which was widely believed to have been designed to siphon votes away from NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 Thomas Suozzi, the Democrat challenging Republican incumbent Nassau County Executive Edward Mangano, a Melius ally. Contributions to Cuthbertson, Petrone and Israel were among $214,067 in contributions to political committees and elected officials from Huntington. The vast majority of the other contributions to Democratic candidates and committees occurred before Melius and Nassau County Democratic Party chairman Jay Jacobs began feuding over various issues. Other major recipients include Mangano, who received $21,400; former Democratic Suffolk County Legis. Lou D’Amaro, who received $17,112.09; former Republican Sen. Alfonse D’Amato, who received $17,000; Suozzi, who received $15,000; and former Nassau District Attorney Kathleen Rice, a Democrat, who received $13,300, but then declined to accept contributions linked to Melius in her successful congressional campaign in 2014. newsday.com Theatleast $1.3millioninpolitical contributionsNewsdaylinkedtoGary Melius,his familymembers,hiscompaniesand hisemployeesarelikelyonlya portionofhis campaign donationsover theyears. Newsday reviewed federal contribution records, which date to 1980, and state candidate and committee records, which go back to 1986. Contributions to county, town, city and village candidates are available going back only to 2006, however. That’s when electronic filing began to be required and older paper records for local contributions have since been destroyed. Newsday was able to incorporate some older local contributions Melius made that were detailed in a 1995 newspaper report. More than 1,100 contributions were found in Newsday’s review of the politi- cal contributions by Melius, his family members, his companies and his employees. Here is a breakdown by political party, including contributions to committees unaffiliated with a party. ! Democratic $755,604.27 ! Republican $461,255.58 ! Conservative $38,850 ! Unaffiliated $36,145 ! Independence $18,450 The largest sums to individual candidates and political party committees are detailed below. The totals include contributions made to campaigns for any office candidates sought. Behind the bare numbers are several deeper and more complicated stories of Long Island politics and Melius’ involvement with it. For example, Andrew Hardwick, a registered Democrat, attempted to run as a third-party candidate for Nassau County executive in 2013. Each candidate’s last elected position and current political party is listed below. NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B28 Under her guidance, the castle was opened for public tours that filled up with schoolchildren and town residents. A nonprofit, Friends of Oheka, was created to support and accept donations for the restoration. Several years earlier, Melius had named Schaffer, a close friend, the castle’s curator. She was deeply involved in creating Friends of Oheka and later became its board president. “The truth was that he performed miracles there and saved us from the horrors of an empty building that was attracting teenagers,” Schaffer said in an interview. Melius began connecting with the influential Cold Spring Hills Civic Association. He invited members to Oheka and allowed them to hold free parties there, as well as association meetings. He hosted holiday events for neighborhood children. Schaffer was the civic association’s past president and an adviser to its board. At her urging, it decided to support Friends of Oheka, arguing that Melius needed an ample revenue stream for the restoration. Goldstein took note of neighborhood concerns and acknowledged them in the restrictions that accompanied the new zoning category. The final proposal allowed for the hosting of only one event at a time, with no more than 220 guests. The castle’s exterior could not be altered and only one small “Oheka” sign was permitted. Perhaps most significantly, the building could not be expanded, limiting the possibility of truly large events. By the time the town board took up Goldstein’s proposed new zoning category in December 1997, civic association members were holding their meetings at Oheka, residents were touring the castle and their children were attending spectacular holiday parties there. The resolution to approve the “floating castle zone” was sponsored by Petrone, Huntington’s supervisor. News accounts reported that hundreds attended the board’s hearing, with 19 speakers, according to the official transcript. Civic association members and professional experts on Melius’ team were among those who spoke in support. Because she was a town attorney, Schaffer said at the meeting that it would be “totally inappropriate for me to comment.” She then presented a slideshow on the castle’s history. Ted Owens, then the president of Friends of Oheka, told the board that permitting “some limited commercial use” was essential to the castle’s survival. “It is only these operations that do generate enough money to maintain and restore the building,” he commented. He said, though, that the operations had to be limited, as they were in the proposed restrictions, to minimize the impact on the neighborhood. Among the opponents was Dunn, the target of Melius’ $10 million suit. She said she wondered why the board would even consider a zoning provision for Melius after he had ignored safety and zoning regulations for years. She asked why they would allow him to operate a large business in a residential neighborhood, disrupting the quiet life she and her neighbors had once enjoyed. “I don’t understand how zoning codes and fire codes and safety laws go completely unchecked,” Dunn said. “I don’t understand how property taxes remain in arrears, yet this board continues to entertain this application. None of this seems to matter.” And she expressed astonishment that no one on the town board felt compelled to come to her defense after Melius’ libel lawsuit, which was based on her public comments and her correspondence to the town as a Huntington citizen. “He seeks out his most vocal opponent and sues her for $10 million, and what does the town board have to say about that?” she said in frustration. “Nothing.” In the end, the board voted unanimously to approve the new zoning category that allowed commercial use of Oheka, a little more than a year after the zoning board had rejected Melius’ last attempt. In addition to Petrone, board members Budd, Israel, Donald Musnug and Susan Scarpati-Reilly approved the zoning. The board’s action, Petrone said, enabled the castle to become “a benefit to that community.” The complaints about noise and fire hazards were routine in issues of this sort and Melius’ donations had nothing to do with the council members’ votes, he said. Petrone said Melius worked hard to win over the community. “That was Gary’s basic mode of opera- B29 JOHNNY MILANO NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION NEWSDAY / AUDREY C. TIERNAN NEWSDAY / THOMAS A. FERRARA The Oheka Castle formal entryway in 2013. The libel suit against Dunn, who declined to be interviewed for this story, was eventually settled. She moved out of the neighborhood. But at the tumultuous hearing, she cautioned that the zoning change was likely the first step toward something further. “I have a very strong feeling that he is just getting warmed up,” she said. She was right. Virtually every important restriction enacted in 1997 was eliminated or eased over the next few years. In 2002, the board relaxed the limit on the number of guests at events and removed the ban on building expansion. In 2003, it allowed construction of a temporary banquet facility. In 2004, it permitted Melius to add signs and approved operation of a 50-room hotel and a health spa, which has yet to be built. Petrone said that while he couldn’t remember specifics, the changes had community support. “Anything that took place at Oheka the community was involved in and spoke for,” he said. Melius portrayed things similarly. His neighbors, he said, told the board, “Give him what he wants. We trust him.” Soon, the number of events was burgeoning. Celebrity weddings hit the entertainment pages regularly. John Gotti Jr.’s lawyer promoted boxing matches through a company called Explosion Promotions. Political Gary Melius at Oheka in August 2014. meet-and-greets became a staple. The board’s decisions were worth tens of millions of dollars. Melius repurchased the castle from Yokoi’s family during a booming real estate market in 2003. He paid $6.9 million, roughly $15 million less than the recorded price that Yokoi had paid 15 years earlier. But Melius still held onto an idea for a bigger score — a condo development on the grounds, on a far grander scale than he had envisioned years before. By now, he had demonstrated that he was a bona fide political player. NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 Restrictions eased The Oheka Castle library in March 2008. Above the fireplace is a portrait of Otto Hermann Kahn, who built Oheka, which is an acronym of his name. newsday.com tion,” he said. “He would come in and want to be part of the political process. My guess? He probably contributed to all the politicians on Long Island.” NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B30 CHAPTER 5 A MULTIMILLION DOLLAR TAXPAYER BAILOUT BY WILL VAN SANT will.vansant@newsday.com newsday.com NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 Milburn Creek LIRR 27 kside N. Broo Ave. Freeport . Ave urn Milb F reeport Village Attorney Howard Colton went to police in July 2009 with a startling accusation: Gary Melius was verbally threatening him and he feared for his safety and that of his family. At the time, Melius was trying to resolve a long-standing legal dispute with the village over his Brooklyn Water Works property, a 4-acre site that he had tried unsuccessfully to develop for two decades and wanted to sell. Colton told Freeport’s police chief by email that Melius was “pressuring” him to force a settlement and claimed to have incriminating recordings and the clout to get him indicted. Melius was using the Nassau County district attorney’s office and its chief investigator, Chuck Ribando, as “his private police force,” Colton wrote. By the time Colton leveled his charge, Melius had remade Oheka Castle into a magnet that drew political, business and law enforcement elites from across Long Island and catapulted himself to a new level of influence. Melius was now more than a man with influential friends; he was a power broker. To unburden himself of the moneylosing Water Works, Melius worked the levers of electoral politics. In Brooklyn Water Works site Sunrise Hwy. Freeport High School Freeport, he put his political weight and pocketbook behind the successful mayoral campaign of Andrew Hardwick, a five-time loser in previous election efforts. Then, after donating $15,000 to the re-election campaign of Democratic Nassau County Executive Thomas Suozzi, he pivoted to Republican Edward Mangano after his surprise 2009 victory over the incumbent. Melius made a $2,500 donation to the apparent victor before Suozzi even conceded in December. Melius estimated in a 2012 interview that Water Works had cost him $13 million over the years. At one point his tax and mortgage liabilities on Water Works exceeded $3 million. Moreover, village residents largely opposed his development plans as too large and intrusive for the neighborhood, and he’d failed to find a private buyer. Melius looked to the Hardwick and Mangano administrations for help. They would come to Melius’ aid by spending a combined $11 million in taxpayer money, all of which went into the pocket of the castle owner or to his various creditors. That figure includes a $3.5 million legal settlement that Hardwick spearheaded despite acknowledging the conflict in his personal relationship with Melius, a $900,000 tax refund from the village, a $500,000 settlement that county officials declined to discuss when it was reached, and $6.2 million that Nassau paid to purchase Water Works — an amount three times the county assessor’s estimated market value. The Mangano administration justified the inflated price by saying that Melius had won valuable development approvals, when, in fact, the village had denied him a building permit. Powerful figures using the public purse to satisfy private ends is not a new story in Nassau. But Melius’ maneuvers with Hardwick and Mangano stand out as a brazen display of political muscle. Melius declined repeated interview requests for this story. In previous public statements, he described himself as a victim of unscrupulous village officials who had tried to “steal” the property from him. “I just want to get out,” Melius told Newsday the year before Nassau bought Water Works. “I want to sell it.” The multimillion-dollar taxpayer bailout that Melius secured shocked even veterans of Long Island business and politics. Desmond Ryan, the retired longtime leader of the Association for a Better Long Island, a real estate trade group, said the county’s purchase of Water Works was a “deal to die for” that left him and others in the industry “stunned.” B31 NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION NEWSDAY / BILL DAVIS A multimillion-dollar taxpayer bailout A frustrating money-loser when liens, which can be purchased by private investors, put him at risk of losing the property, according to a lawsuit. Melius’ ownership was briefly in question after a group of private tax lien investors obtained deeds, but a judge in 2006 declared Melius the rightful owner, saying he’d not been properly notified of deadlines he faced to pay the liens off. Even so, Melius in 2008 sued the village, Glacken, other village officials and Nassau County, alleging a conspiracy to steal Water Works by secretly transferring the tax liens to the investors. Melius had first raised his allegations years before, and FBI investigators began questioning those involved in 2006, according to court The Brooklyn Water Works site in Freeport in March 1998. records. At a campaign event in early 2009, Glacken told village residents that Melius’ conspiracy lawsuit was an attempt “to extort money from you.” Melius sued Glacken for defamation and lost the case at the state appellate level. Hardwick becomes mayor Melius needed a friendlier administration in Freeport. And Hardwick, an aspiring politician with a pugnacious style, needed help if he was ever to win an election. CONTINUES on B33 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 In the 19th century, the City of Brooklyn undertook a massive public works project to supply its residents with water from Long Island. The project’s largest pumping station — a Romanesque Revival redbrick structure with castle-like towers and huge arching windows — was built near Freeport’s Milburn Creek. Throughout the 20th century, the station, known as Brooklyn Water Works, was used less and less and was shut down in the 1970s. Melius saw opportunity in the station’s ruins in 1986 when he purchased the then-county-owned property for $1.4 million. But Water Works quickly proved a frustrating moneyloser. Melius feuded with village mayors and residents over development proposals and saw deal after deal dissolve into lawsuits as the once-grand structure slowly collapsed, becoming a graffiti-covered eyesore. Melius came to bemoan the purchase and engaged in a long battle with then-Mayor William Glacken over property tax payments. What Melius’ attorney dubbed a “business decision” for Water Works involved remaining delinquent on his village and county taxes, making good only newsday.com “You buy this piece of property, you don’t get what you want and now you want to unload it back on the county?” Ryan said. “What, are you kidding me?” NEWSDAY / CHRIS WARE NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B32 NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com Melius, Hardwick and an FBI wire BY WILL VAN SANT will.vansant@newsday.com In 2010, an FBI wire caught Gary Melius and Freeport Mayor Andrew Hardwick appealing for the Freeport Police Benevolent Association president’s support of a personnel move within the village police department. The influential PBA president, Shawn Randall, said in a deposition the following year that in a conversation he recorded, Melius and Hardwick had offered to help his union’s members obtain foreclosed homes in the village. Randall gave the deposition in a fed- eral civil rights case brought against Hardwick and the village alleging discrimination in the police department. His account reveals the extraordinary degree to which Melius, a private citizen, was involved in the workings of Freeport government. Randall testified that he’d been approached by Michael Craft, who was then an FBI special agent and said he was trying to build a public corruption case against Hardwick. Craft asked him to record conversations with Hardwick, Randall said. Randall said he wore a wire at a meeting Melius had arranged that included Hardwick. Randall testified that the conversation “went on for hours” and that Hardwick and Melius were focused on getting him to back the promotion of a detective who was a Hardwick favorite to be assistant chief. The two men made an offer to Randall, he testified, telling him “they would help PBA members get” as many as 400 foreclosed homes. “Help them purchase the homes?” an attorney asked Randall. “Yes,” Randall said. “And how would they help? When you say ‘they,’ who are you referring to?” “Both of them.” Andrew Hardwick in July 2012. “Gary Melius and Mayor Hardwick?” “Yes.” “And how would they help the PBA members purchase the homes?” “I didn’t ask.” Randall testified that he had refused to support the detective’s promotion, citing a lack of experience. The detective was not promoted. Neither Randall, who is still the PBA leader, nor Craft agreed to be interviewed. Hardwick was not charged with any crime by the federal authorities. The case in which Randall testified, which involved accusations of discriminatory hiring in the Freeport Police Department, is continuing. Schlesinger and Hardwick declined to be interviewed. Gary Melius inside the Brooklyn Water Works site in January 1990. Howard Colton in February 2017. CONTINUES on B34 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 “status report” on settlement talks, he wrote. When Colton told him that no report was ready, according to the complaint, Melius exploded. “You don’t know who you are [expletive] with,” Colton said Melius yelled. “I’m coming after you. I’m going to get you. I’m going to get you indicted and the rest of you [expletive].” Many people who have interacted with Melius over the years, including business adversaries, have experienced this boorish and bullying side. “If you punch me in the nose, I am going to punch you back,” Melius told Newsday editors in April 2017. According to Det. Sgt. Raymond Horton’s summary of what Colton told him, the village attorney brought Melius’ alleged tirade to Hardwick’s attention. Colton “reported that Mayor Hardwick had told him that Gary Melius has an anger management problem and to let cooler heads prevail,” the sergeant wrote. In his complaint, Colton requested newsday.com Freeport Village Attorney Colton charged that within weeks of Hardwick taking office in April 2009, Melius’ intimidation campaign began, according to internal records and emails that Newsday obtained. Melius first unnerved Colton by instructing him to report to the Nassau district attorney’s office, according to an email the attorney sent in July of that year to then-village Police Chief Michael Woodward. Colton wrote that Melius told him he was “personal friends” with the office’s chief investigator, Chuck Ribando, and that an indictment “is coming” of Colton’s predecessor, Joe Edwards. “Melius informed me that I should go in on my own before, ‘they come and get you,’ ” Colton wrote to the police chief. Edwards, also a Melius adversary over Water Works, was never indicted. He did not return calls for comment. Ribando was a retired 20-year NYPD veteran when he joined the Nassau district attorney’s office in 2006 to lead the investigations division. He was a regular at Oheka, according to Melius and castle guests in law enforcement. When a wedding reception for Ribando’s daughter was held at Oheka in 2012, an overnight affair that saw all the castle’s hotel rooms booked, Melius said he charged a discount. In a 2014 interview, Melius said that he had been unable to book an event for that date, and that under such circumstances, he typically lowers his prices. Melius kept calling in the summer of 2009, according to Colton, and on July 22 Colton filed a formal complaint with village police. Melius had phoned him that day and asked for a NEWSDAY / THOMAS A. FERRARA Allegations of intimidation that no further action be taken in the matter, but then followed up with an email to Chief Woodward that detailed these events: On July 28, 2009, after he said he and Ribando had exchanged telephone calls, Colton wrote that the two met and Ribando questioned him about the alleged tax lien scheme that Melius argued was designed to defraud him of Water Works. Colton said he told Ribando he had little knowledge of the matter and was not involved. Colton told the chief: “Melius has made several veiled threats at me in the hopes of pressuring me to force a settlement of the Water Works civil litigation,” he wrote. “Melius has informed others that he has tape recordings of me, but when asked to produce them, he cannot. . . . It is obvious that this is being used as a pressure tactic.” The following day, July 29, Colton met with Hardwick and Melius at the Grand Lux Café in Garden City to talk about the settlement, according to the email. During the meeting, Colton wrote that Melius took a call from a man named “Chuck” who “clearly” was Ribando. “I have concerns that the County DA’s Office has been corrupted by Melius and he is using them as his private police force,” Colton wrote to Woodward. The district attorney’s office said that it never received a complaint from Colton or Freeport police about Melius’ conduct and his ties to Ribando, who declined to be interviewed for this story. However, another public official notified the district attorney’s office of Colton’s concerns, according to emails Newsday reviewed. At the time Colton lodged his complaint, Kathleen Rice, now a congresswoman, was Nassau district attorney. Her spokesman Coleman Lamb said in an email that any suggestion Melius had corrupted the office was “ludicrous.” Lamb added that he could not “speak for Chuck Ribando, but I can certainly say that he did not run the DA’s Office. He had bosses, and he couldn’t indict anyone.” A month after Colton’s July 29 meeting at the Grand Lux Café, and after years of antagonism, it became clear that Freeport’s posture toward Melius had undergone a striking reversal, as would the village attorney’s. The village agreed to settle its tax dispute with Melius by reducing the assessments levied on Water Works over the prior decade and cutting him a $900,000 refund check. Six weeks after the meeting, the village settled Melius’ conspiracy lawsuit for $3.5 million. Hardwick pushed for the settlement, Mayor Kennedy said. Attorneys close to Hardwick presented cost estimates justifying the move, NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION NEWSDAY / J. CONRAD WILLIAMS JR. B33 A captain in Freeport’s volunteer fire department and former assistant to two Freeport mayors, Hardwick lost a race for state Assembly in 1994 as a Republican; failed to make the ballot in 1995 and 1997 after holding himself out as a potential candidate for Nassau Legislature; then lost a race for village trustee in 1999 and unsuccessfully challenged Glacken for mayor in 2005. He filed to challenge Glacken again in 2009 — this time with Melius as an ally. Melius asked Nassau Democratic leader Jay Jacobs to back Hardwick. Jacobs recalls being reluctant. Glacken, however, was a Republican. Melius had given the Nassau Democratic Party nearly $40,000 in the previous three years. Jacobs and the party gave Hardwick $3,580. Two weeks before Election Day, Hardwick received a combined $2,997 in donations from Melius’ wife, daughter and former son-in-law, Richard Bellando, records show. The donations plus Jacobs’ money totaled nearly a third of what Hardwick raised. On Election Day, workers from Oheka Castle were out campaigning for Hardwick, according to current Mayor Robert Kennedy, who ran on a slate with Hardwick for village trustee. Hardwick won by 328 votes of 5,842 cast. Hardwick’s combative streak and sometimes curious actions during his single mayoral term would cause controversy. Here’s a sampling: When sworn in, he had a band play “Hail to the Chief,” which is used to announce the president of the United States. During his first weeks in office he had the village hire a private security team to guard him at a cost of nearly $10,000, citing unspecified threats. He and an aide toured China on a “trade trip” paid for by the village. He used the village’s automated phone system to contact residents with a recorded call that attacked a political opponent. He apologized after hosting the vice president of El Salvador, who had participated in anti-American protests after 9/11. And in his unsuccessful re-election effort, he sent out a mailer falsely claiming that he had the personal endorsement of then-President Barack Obama. As mayor, Hardwick, a regular at Oheka Castle parties that drew cops and politicians, worked to resolve Melius’ Water Works woes and put millions of dollars in the pockets of the castle owner and a close Melius ally. Three months after Hardwick’s swearing-in, the village retained Steven Schlesinger’s law firm as an outside counsel. A Melius poker pal whose 2014 wedding was held at Oheka, Schlesinger was then the Nassau Democratic Party attorney. Records show that his firm collected $1.1 million from cases it was assigned during Hardwick’s single term. NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com NEWSDAY / MICHAEL E. ACH NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B34 Incoming Nassau County Executive Republican Edward Mangano on Dec. 2, 2009, the day after incumbent Thomas Suozzi conceded the election. Kennedy recalled, suggesting that if the village lost, it would have to pay attorney fees for both sides, which could total at least $4 million on top of any judgment for Melius. When the settlement was voted on, two trustees abstained. Hardwick and his two running mates, including Kennedy, voted for the deal. In a written disclosure filed with the village, Hardwick acknowledged that he had a potential conflict of interest. Melius was “personally known to me,” he wrote, and as a result he would “prefer to abstain.” But without his vote, the settlement would fail, Hardwick said, exposing the village to the risk of “burdensome taxes or, in the worst case, a potential municipal bankruptcy.” Glacken, the former mayor who is himself an attorney, said in an interview that the village had no liability and Melius no case. Glacken said Melius’ lawyers had not even deposed him or other defendants. The Hardwick administration “just rammed this thing through,” he said. “If I had still been there, we would not have settled the case,” Glacken said. “We would not have given them a dime.” tives; state and county police officers; Robert Hart, the former head of Long Island’s FBI office and then-chief investigator for State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman; FBI agents; Rice; and Ribando. In August 2010, Freeport put Colton’s father, a prominent rabbi, on its payroll as a $150-an-hour community liaison. Melius also hired Colton’s father as a consultant for Oheka Castle, according to the attorney’s deposition in the discrimination case. A personal spokesman for Colton, John McDonald, initially said Colton declined to be interviewed because of a cooperation agreement with federal law enforcement. McDonald declined to say what the cooperation concerned then insisted after the fact that his comments had been off the record. Then, more than 48 hours after this story appeared online, he contacted Newsday to clarify that Colton is a witness for the FBI and that on advice of his counsel, Colton could not comment. A relationship thaws A bond with Mangano By summer 2010, the relationship between Colton and Melius had undergone a remarkable change. No longer an adversary, Melius had become Colton’s regular host and the attorney began attending twicemonthly dinners at Oheka, according to a deposition he gave the following year. In an unrelated case involving allegations of discrimination in the Freeport Police Department, Colton said in 2011 that Oheka dinner guests included lawmakers; county execu- As he won settlements from a more amenable Freeport, Melius also strengthened his bond with Mangano, then the incoming county executive. Mangano is awaiting trial on federal corruption charges in a case unrelated to Water Works. Melius had supported Nassau Executive Suozzi’s re-election campaign, but nine days after the Nov. 3, 2009, election, amid a recount and mounting indications that Mangano had won an upset, Melius gave him a $2,500 donation. Suozzi conceded on Dec. 1. During his first term, Melius, his wife, Pamela, and Bellando would donate a combined $17,900 to Mangano. Today, Melius and Mangano are friends. They’ve traveled to New Jersey together to shop for dachshund puppies and to Las Vegas to gamble. Mangano has been a frequent guest at Oheka, appearing not only at regular private cigar parties, but also as an honored guest at large functions. “I love him,” Melius has said of Mangano. “I think he’s the best political guy.” With Mangano in office, Melius reaped rewards. The day superstorm Sandy struck in 2012, for instance, the county awarded a $655,000 emergency debris cleanup contract to a Melius design and construction firm, ArchCon. The contract was among several awarded without bidding for debris removal. Available Nassau records show no previous county payments to ArchCon for debris cleanup or anything else. In an interview a few years later, Melius said, “Everything was done above board.” In 2010, nine months into Mangano’s term, the county settled its portion of the Water Works lawsuit — in which Melius accused Nassau of having conspired with Glacken to wrest the property from him — for half a million dollars. Asked at the time to explain the decision, the county declined. Varying appraisals Meanwhile, with the two settlements won, Melius renewed efforts to develop Water Works, proposing a complex that violated village zoning in multiple ways. His plan called for a six-story, 140-unit apartment building and quickly drew fire. Under pressure The Water Works site in March 1998. two new appraisals. By then, Long Island property values had crashed under the weight of a historic economic slump. Nonetheless, the appraisals valued the property at $6.3 million and $6.9 million — more than double the higher estimate from five years earlier. During the same time period, the median value of condos and co-ops in Freeport had dropped 24 percent, from $420,000 to $318,000, according to the real estate data firm Zillow. Countywide, the decline was 21 percent. Neither the appraiser who arrived at the $6.3 million figure nor the appraiser who produced the $6.9 million figure responded to multiple interview requests. In April 2012, when the county assessor’s office last estimated market value for the property was $2.1 mil- The deal gets done In September 2012, Nassau paid $6.2 million for Water Works. Of that, $3.2 million went to Melius and $2.6 million to his mortgage lenders. Another $400,000 covered taxes owed on the property. For Melius, the burden was lifted. Twenty-one days after legislators voted for the sale, Melius’ wife made a $1,500 contribution to Denenberg. In the five years before the Water Works vote, Melius had given him $1,950; in the year after, Melius and his wife donated an additional $1,800. In an interview, Denenberg, an attorney disbarred in 2015 after pleading guilty to stealing $2 million from a client, defended the purchase, calling it an important piece of property for Freeport residents. Nonetheless, he acknowledged, the $6.2 million price tag seemed inflated. “I had always thought that the price was less than half of that,” he said. NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 traction. Nassau should buy the property with money set aside to preserve undeveloped land, he argued. Denenberg had suggested this before and had the site placed on the county’s list of potential acquisitions in 2006. It was situated along the South Shore, where open land is scarce, and bordered a nature preserve that Denenberg said he wanted to protect from development. In 2006, the deal stalled over money. Two appraisers hired by Nassau pegged its value at $1.6 million and $2.7 million. An offer of $3 million was discussed, Denenberg said, but it wasn’t enough for Melius. In a court filing a few years later he said that he had once had a deal to sell the property for $8.5 million, but that it fell apart. In 2011, the Mangano administration turned its attention to buying the property for open space and ordered newsday.com from residents and environmentalists, Melius dropped the number of units to 121, a figure still almost 50 percent above what was allowed. Dozens of angry residents attended village Landmarks Commission hearings. “I don’t need a gigantic monstrosity like that in my neighborhood,” one said. Another described the proposed plans as “scary . . . like looking at a big box store on Sunrise Highway.” Only a handful of residents spoke in favor. Melius’ attorney wrote a letter threatening to sue the commission. “This is an attempt at intimidation!” one member of the board seethed in an email to her colleagues. But the final vote was 4 to 4, which under board rules kept the plan alive. Before the development approval process could proceed, however, an alternative proposal from then-Nassau Legis. David Denenberg, who represented parts of Freeport, gained NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION NEWSDAY / BILL DAVIS B35 lion, the Mangano administration and Melius drew up a sale contract for $6.2 million. Explaining the price increase to county legislators the following month, the acting director of the Nassau Office of Real Estate Services, Michael Kelly, said that “time has gone on” and that Melius had obtained additional approvals to develop the property, “which, of course, raises the value.” Both sets of appraisals assumed the owner would turn the property into a large residential complex with 121 units. Melius didn’t have approval to build any units, however, and under Freeport’s density rules the complex he proposed could contain at most 78. Freeport’s superintendent of buildings had repeatedly rejected Melius’ permit applications in 2011, noting the many ways his plans didn’t comply with Freeport law. The proposed apartment building didn’t provide enough parking, the superintendent wrote; it would take up too much of the parcel; and buildings taller than five stories were illegal. “We’re getting a phenomenal deal,” Kelly, who did not return calls seeking comment, told county legislators. They approved the sale unanimously two weeks later. Two days after the vote, Melius’ wife, Pamela, donated $3,500 to Mangano. The Nassau Interim Finance Authority, which monitors the county’s spending, was less sure the deal made sense. Its board voted 2 to 2 — a tie that let the sale proceed. However, even the two members who voted in favor questioned the price. “There’s a lot not to like about this transaction,” said one of them, Chris Wright, “whether it’s the political motivation, the timing or the value.” Nonetheless, Wright said, the use of long-term debt to finance the purchase was sensible, as was using money dedicated for open-space preservation. NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B36 CHAPTER 6 A POLITICALLY MOTIVATED ARREST ON A PUBLIC BUS BY WILL VAN SANT will.vansant@newsday.com NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com A sergeant and two plainclothes detectives from the Nassau County Police Department stopped a bus in Hempstead Village on an October evening in 2013 and arrested Randy White as he was traveling to visit his nieces. White’s apprehension and the incarceration that followed came days after he had given critical courtroom testimony against Andrew Hardwick, an ally of Gary Melius, that threatened to upend the Oheka Castle owner’s effort to sway the pending Nassau County executive race. White’s testimony so troubled Melius that he telephoned Nassau Police Commissioner Thomas Dale, a friend whom Melius had recommended for the job, to say that Hardwick’s county executive campaign “wanted to file a perjury charge against” the 29-year-old White, according to findings District Attorney Kathleen Rice issued after her office investigated the case. When Dale’s officers could not find evidence of perjury, they found another justification for apprehending White: an outstanding warrant — one not even entered in the department’s computer system, according to a sergeant involved — issued for White’s failure to pay a fine in a mis- demeanor case involving bootleg DVD sales. Following Melius’ call, police jumped White’s open warrant ahead of 50,000 others. Half were arrest warrants, which involve criminal violations and are supposed to be the department’s priority. Roughly 2,000 were felony warrants. White’s warrant was a bench warrant, typically issued for noncriminal violations like failure to pay traffic tickets. At the time, there were 25,000 open bench warrants in Nassau. Hardwick was then a long-shot, third-party candidate for Nassau executive. Victory was unlikely, but his fledgling campaign had the potential to draw votes away from the Democratic challenger to Republican Nassau Executive Edward Mangano, a Melius friend and ally. The political motivation for White’s arrest became all the more apparent when the sergeant served him with a civil subpoena from Hardwick’s attorney while White was in police custody. The campaign of Hardwick, a former Freeport mayor, wanted White back in court to re-examine him. Earlier he had testified that he’d been paid by the signature when collecting petitions for Hardwick, a violation of state election law that could endanger a campaign. In targeting White, who has a learning disability, Melius acted not against another player in the bruising arena of Long Island politics, but a vulnerable civilian whose sworn court testimony had created a political obstacle. Top Nassau law enforcement leaders, some with personal ties to Melius, led the arrest effort. Rice’s investigation determined that the incident, while troubling, did not include criminal misconduct warranting prosecution or involve Mangano or those in his administration. Newsday, however, has discovered unreported information that raises new questions about the scandal. Key police officials at the center of the White matter told Newsday they were interviewed not by Rice’s investigators but by Nassau police internal affairs personnel. They include Dale’s chief of detectives, John Capece, who helped lead the effort to apprehend White. Interviews given to internal affairs investigators are generally criminally inadmissible, meaning Rice’s inquiry was conducted in a way that complicated or even precluded potential prosecutions. In an interview, Capece told Newsday that he cautioned Dale against arresting White. But Capece said the police commissioner confided that he had no choice, saying that “he was getting pressure from people across the street.” Mangano’s office was across from police headquarters, and Capece said he understood Dale to be referring to the county executive, a Melius ally and the potential beneficiary of the election scheme, and his deputy, Rob Walker. Dale, Mangano and Walker declined interview requests. They were among several pivotal figures in the White drama who chose not to answer questions from Newsday. While the scandal led to Dale’s resignation and Capece’s decision to retire rather than be demoted, Melius and many public officials who abetted White’s arrest paid no price, unlike Nassau taxpayers. White, whose father said his son was left “psychologically bent” by the episode, brought a lawsuit against Nassau that alleged an array of civil rights violations and collected a $295,000 legal settlement in 2016. Bennett Gershman, a Pace Law School professor and former public B37 NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION HOWARD SCHNAPP A politically motivated arrest on a public bus Independence Party ties leader. MacKay named Melius his “chief adviser” that year in an effort to take the party national. The designation elevated him in a party whose modest size belies its clout, particularly in judicial races, and that’s described by some in state politics as an elaborate con. In part, that’s because new voters have mistakenly registered as Independence Party members when they intended to register as independent of any party. “They don’t stand for a thing,” GOP gubernatorial candidate Rob Astorino said of the party’s leadership during his failed 2014 run, “other than jobs for themselves.” Astorino was expressing a frequent criticism, that the party is effectively a mechanism to exert influence and generate income for its leaders, rather than a standardbearer for any political ideology. It’s Randy White in December 2013, months after his arrest in Hempstead. a criticism party leaders reject, but one voiced by editorial boards and good-government advocates across the state. At the time of the 2013 election, Oheka Castle had become the party’s de facto operations hub, a place to hold fundraisers and interview candidates. MacKay had named Richard Bellando, Melius’ employee, friend and former son-in-law, as the party leader in Nassau. And Oheka had put MacKay on its payroll in various positions. MacKay declined to be interviewed for this story. Spoiler candidates The hand of the Independence Party was evident in two aborted CONTINUES on B38 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 The White scandal sprang from machinations to keep Mangano in office. In 2009, Mangano won an upset victory over Nassau Executive Thomas Suozzi by 386 votes out of nearly a quarter-million cast. Plans were made to prevent any such scare in the 2013 rematch. They involved using third-party spoiler candidates to siphon away the votes of environmentalists and African-Americans who would be likely to support Suozzi, a Democrat. Melius and his wife, Pamela, had donated nearly $18,000 to Mangano during his first term, and Melius had reason to want him re-elected. With Mangano in office, Nassau had inked a real estate deal, legal settlement and contract with Melius worth more than $7 million to the castle owner. The county also tweaked its rules on the use of ignition interlock devices that combat drunken driving, benefiting a company in which Melius had a stake. Backing Mangano in 2013 after having supported Suozzi in 2009 was the Independence Party, a controversial third party with which Melius and his beloved Oheka Castle had become deeply enmeshed. In 2008, Melius established an alliance with Frank MacKay, the party’s state and Suffolk County newsday.com corruption prosecutor, expressed dismay not only at the actions of Melius and Nassau police, but also at the failure to pursue criminal charges in “a case of rank corruption.” “You’ve got this power broker who picks up the phone to the chief of police and gets a man yanked off a bus and arrested,” Gershman said. “It’s terrifying.” NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com Invalid signatures The Independence Party’s attorney was involved in the second effort, which featured Hardwick, who tried to run as a candidate for the new “We Count” Party. After a tumultuous term as Freeport mayor — during which he backed $4.4 million in settlements for Melius in cases involving his troubled Water Works property — Hardwick had lost a re-election bid. Hardwick’s party was a creation of Melius and his allies. Between July 2013 and the November election, records show Melius, his family and one of his businesses gave We Count $38,839, more than 80 percent of the party’s total. Because Hardwick is black, many people in Nassau politics saw his candidacy as an effort to siphon African-American votes from Suozzi. The candidate, however, insisted that his run was a stand for the middle class and against corruption. “People are sick and tired of the same old lies and deceit,” Hardwick said in a campaign video. After Nassau Democrats challenged HOWARD SCHNAPP Hardwick’s petitions in state court, state Supreme Court Justice F. Dana Winslow barred him from the ballot, declaring that his petition effort had been “permeated with fraudulent practices” of which Hardwick had “knowledge.” While the case was in court that October, the board of elections found 2,700 of Hardwick’s 8,400 nominating signatures invalid. It was suspected that thousands more were outright forgeries, but Winslow, with the consent of both parties, ceased his review after identifying more than 100 such bogus signatures. Asked to identify his largest campaign donor, Hardwick replied under oath, “I don’t know.” At the time Hardwick testified, Melius was his sole donor. His campaign treasurer was an Oheka employee, and a campaign worker testified that she had delivered nominating petitions to Hardwick at Oheka. Independence Party attorney Vincent Messina, whose firm collected $16,000 from We Count’s largely Melius-funded treasury, represented Hardwick in court. Hardwick declined interview requests. Nassau County Executive Edward Mangano with Nassau Police Commissioner Thomas Dale in January 2013. Dale resigned at the end of the year. A call to the commissioner Randy White emerged as a key witness in the Hardwick case. As a teenager, White had compiled a criminal record, including convictions for attempted robbery and felony drug possession. Through his 20s, however, White stayed out of legal trouble, save for an occasional misdemeanor violation for selling bootleg DVDs. He lived at home with his father, Rassan Hoskins, a Nassau Democratic Party committeeman, and struggled to find work. When Hardwick operatives asked White to collect signatures to get Hardwick on the ballot, White agreed. “Randy naturally wanted to make some money,” Hoskins said. “But I told Randy, ‘Man, you can’t work for Hardwick, I am a Democrat.’ ” Hoskins said his son “is not sophisticated enough” to always recognize when he’s being used and can be truthful even when doing so could cause him grief. Under questioning in the Hardwick case, White testified that he’d been paid by the signature, which is prohibited by state election law in part because it’s thought to incentivize fraud. Two days later, on Oct. 4, Hardwick’s attorney Messina unsuccessfully attempted to introduce a telephone call recorded by campaign operatives in which it was alleged White contradicted his damaging testimony. Within hours, according to findings that District Attorney Rice released six weeks later, Melius called Nassau Police Commissioner Thomas Dale, whom he had recommended Mangano appoint, and said Hard- NEWSDAY / CHRIS WARE efforts to use third-party candidates to strip votes from Suozzi and to aid Mangano’s re-election. The first involved 25-year-old Phillipp Negron, who was recruited to run for executive on the Green Party line and had landed a public works job with the Mangano administration just days before his campaign became public. Negron would testify in an election law case involving his campaign that he decided to run after speaking with his stepfather, Timothy Williams, a Mangano appointee and chairman of the Nassau Industrial Development Agency. After the talk, he said, a woman brought a Green Party registration form to his home. Negron testified that he and his stepfather next met a man at a diner who brought paperwork to sign. “When I registered to be a Green Party member, I expressed my interest in running,” Negron said. “Next thing I know, I’ve been nominated.” The man he and his stepfather met at the diner was Brian Nevin, Mangano’s former chief spokesman and manager of his re-election campaign, Negron testified. The bulk of the petition signatures Negron needed to get on the ballot would be collected by Nevin and other Republicans working for Mangano, court records would establish. Robert Pilnick, an Independence Party officer, was also among the handful of political operators who collected signatures, county election records show. Democrats challenged Negron’s petitions in court, alleging that the campaign was a “fraud” and that some signatures were from reluctant Oheka Castle employees. After two days of testimony, Negron withdrew from the race. NASSAU COUNTY GOVERNMENT NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B38 Chuck Ribando in December 2014. Andrew Hardwick in July 2012. wick’s campaign “wanted to file a perjury charge against” White. Dale sent some of his top people, a department attorney and Capece, the chief of detectives, to the First Precinct in Baldwin, according to the Rice findings. There they met with Hardwick campaign operatives and Messina, the candidate’s attorney who also represented the Independence Party, to discuss the perjury charge. The recorded phone call turned out to be inaudible, Capece said in an interview, and he told Dale that he would not arrest White for perjury. Police soon found other grounds, however. Sal Mistretta, then an Oheka regular and a Nassau police sergeant who led the pistol license division, played a central role in the scandal. At the time, Mistretta was backing Mangano’s re-election. He gave $500 to the incumbent on Oct. 18 and was listed as a contact on a flyer for an Oct. 28 Mangano fundraiser. In a recent interview, Mistretta said that he checked the department’s electronic warrant system on the day of the First Precinct meeting and found no hits for White. Nonetheless, he said, an outstanding warrant was located, presumably in court filings, and faxed to the precinct after 5 p.m. The warrant involved White’s failure to pay a $175 misdemeanor fine, $25 victim assistance fee and $50 DNA databank fee levied in a bootleg DVD case in which White was sentenced to 14 hours of community service after he pleaded guilty. All guilty verdicts in New York State require the levying of such fees. The warrant had been issued on Aug. 26, almost six weeks before the meeting at the First Precinct, and until that moment it had apparently not been an urgent matter. Between the day it was issued and the First Precinct meeting, White had appeared in court several times and spent 10 days in jail on another DVD case, but he had not been picked up on the warrant. When news of the warrant reached Dale, he ordered White located and arrested, despite what Capece said were his cautions to the commissioner. Using information from an individual Dale would later describe to investigators as a “confidential source” who appears to have tracked White, he was located the following evening. A sergeant and two detec- B39 at more than 480,000 statewide, according to the state. That’s because many people have registered as Independence Party voters mistakenly, The New York State Independence actually intending to register as indepenParty was the creation of three dent of any party, critics contend. Rochester-area political mavericks, “The name of the Independence including Thomas Golisano, a billionaire Party is misleading: it neither represents businessman and philanthropist who ‘independence’ nor is it ‘independent’ of ran unsuccessfully for governor three the major parties,” Susan Lerner, directimes, Newsday stories at the time tor of the good-government group show. Common Cause New York, wrote in an The party, according to the stories, email. first appeared on the ballot in 1994 and Though some candidates have pubwas envisioned as a home for disillulicly questioned or even condemned the sioned centrists who no longer felt party’s influence on state politics and welcome in either the Republican or rejected its backing, others prize its line Democratic parties. on Election Day. The state’s arcane Today’s Independence Party has a fusion system allows candidates to pool similar self-conception. According to its vote tallies when they run on more than website, the party “seeks to foster one line. Party support in tight races and balanced, pragmatic leadership and an judicial elections can provide the winend to partisan stagnation.” ning margin. Though supporters still portray the Take the 2012 Supreme Court races party as a nonideological alternative to a on Long Island. Twelve candidates ran, failed two-party system, prominent with the top six vote-getters winning a editorial boards and high-ranking politijudgeship. The six winners all had Indecal leaders across the state have dependence Party support; the six losers scribed it today as devoid of conviction did not. Party support more than covand chiefly concerned with serving the ered the difference between interests of its leaders. the sixth-place victor and Frank MacKay, who leads seventh-place loser. the Suffolk County IndepenRepublicans in the State dence Party, emerged as the Senate in particular enjoy a state party leader in 2000 close alliance with the Indefollowing courtroom battles pendence Party. In 2013, the and an intraparty feud. Moreland Commission, MacKay established himself which Gov. Andrew M. as a savvy electioneer, strikCuomo convened to study ing deals with major party public corruption but discandidates eager for Indepen- Frank MacKay banded after less than a year, dence Party backing. revealed that $350,000 from the houseMacKay tapped Gary Melius as his keeping account of the Senate GOP had chief adviser in 2008 for an effort to been transferred to the housekeeping take the party national, and Oheka account of the Independence Party. Castle has served as an operations hub By law, housekeeping money is for the Independence Party. supposed to be used only to cover party MacKay has earned income as an Oheka employee. On financial disclosure expenses like maintaining a headquarters and paying staff, not to support forms, which ask for reported income in candidates. However, the money transbroad ranges, MacKay listed earnings ferred from the Senate GOP to the from “Oheka Castle Catering, Inc.” of Independence Party was used to pay for between $345,000 and $525,000 from attack ads against Democratic candi2012 to 2016. During the same period, dates. MacKay reported he collected income While Senate Republicans have of between $315,000 and $510,000 benefited from Independence support, from the state and Suffolk IndepenIndependence officials have also coldence parties. lected salaries from GOP elected offiMoney flows in the other direction, cials. Among them are Tom Connolly, too. Expenditure reports show that the the Independence Party’s vice chairparty’s Chairman’s Club and Nassau man, and Bellando, the party’s Nassau Club have paid nearly $250,000 to chair and Melius’ former son-in-law. Melius; his businesses; his former sonConnolly was paid $88,691 in 2017 as in-law, Richard Bellando, who works at director of operations for state Sen. Phil Oheka Castle and is the party’s Nassau leader; and to two nonprofits that Melius Boyle (R-Bay Shore). Bellando collected $30,762 last year as a legislative aide for controls. the Senate GOP majority operations Critics have labeled as misleading the office. party’s enrollment figure, which stands BY WILL VAN SANT Nassau Police chief of detectives John Capece in April 2008. know if the police think I got Andrew kicked off the ballot.” Link to prosecutor’s office CONTINUES on B40 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 Rice, who is now a congresswoman, began her investigation shortly after details of White’s arrest became public and would convey her findings to Mangano by letter, assuring the county executive that it was “appropriate to note our investigation has uncovered nothing to suggest that you or members of your administration were involved in the case against Mr. White.” Chuck Ribando, Rice’s chief public corruption investigator whom Mangano would hire the following year as his deputy for public safety, helped lead the White inquiry. By Melius’ own account, Ribando had been a frequent guest at Oheka and the two men enjoyed a friendship that went back years. In 2009, Freeport Village Attorney Howard Colton alleged that Melius was using Ribando to bully him. Melius was engaged in an effort that eventually succeeded to settle a lawsuit he’d brought against the newsday.com tives handcuffed White on the public bus and took him to the First Precinct, where he was given a strip and cavity search, according to his federal civil rights complaint. White was then taken to police headquarters, where Mistretta served him a civil subpoena drafted by Messina, the Independence Party’s attorney, who was representing Hardwick. The subpoena ordered White to appear in court the following Monday so that he could be questioned about his prior testimony. Mistretta said he’d been given the subpoena by Brandon Irizarry, who worked on the Mangano and Hardwick campaigns. Though not a police officer, Irizarry mixed regularly with Melius and his many law enforcement guests at Oheka. Mistretta would later insist that he did not know that what he’d passed along was a subpoena. Police next took White to the county jail, where, his federal complaint states, he was again subject to strip and cavity search. A judge released him the next day. In comments to Newsday shortly after he left jail, White said he felt fearful and perhaps a bit paranoid. “It’s got me scared to go outside my house,” he said, “because I don’t HOWARD SCHNAPP NEWSDAY / ROBERT MECEA will.vansant@newsday.com NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION Independence Party’s road to prominence village involving his Water Works property. Colton went to village police to complain that Melius had corrupted the district attorney’s office and was using Ribando and the threat of getting Colton indicted to secure a settlement. At one point, Colton told police, he met and was questioned by Ribando after Melius told him to seek out the investigator before the district attorney’s office came to “get” him. Ribando declined repeated requests for comment. In 2012, when Ribando’s daughter’s wedding reception took place at Oheka, an overnight affair that saw all rooms booked, Melius said in an interview that he had charged a discount and suggested that may have been because he’d been unable to line up any other event for the date in question. Mistretta and others who frequented Oheka said Ribando regularly attended the cigar parties Melius held at the castle and enjoyed Johnnie Walker Blue Label Scotch. On Election Day in November 2013, as the Rice inquiry was underway, Melius sent Ribando a get-out-thevote email that Newsday obtained through a records request. “Just a reminder to vote today,” Melius wrote. “Please consider voting Row E, the Independence Line — where you will find the best of all parties.” A November 2013 ballot showed Mangano and Rice were among dozens of candidates featured on the Independence Line. NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com Internal affairs involvement Rice’s letter announcing the results of the inquiry was released on Dec. 12, 2013. She concluded there was no evidence of criminal misconduct by police brass. While the case had “obvious political overtones” and Dale’s decision to involve himself was “a judgment potentially fraught with peril,” Rice found that “the department’s decision to target the subject of an open warrant was not a violation of criminal law.” However, Rice noted that her office would continue to investigate White’s having been served with a civil subpoena by the Hardwick campaign while he was in police custody, which she called “a deeply troubling aspect of this case.” “My office conducted a thorough investigation into these serious allegations,” she wrote. Yet Mistretta and Capece, two lawmen central to the scandal, said in interviews that Rice’s investigators never spoke to them. Mistretta was the sergeant who delivered the Hardwick campaign’s subpoena to White while he was in police custody — the aspect of the case that Rice described as “deeply troubling” and “still under investigation by this office.” Capece, the former chief of detectives, had helped to carry out Dale’s arrest order. Mistretta said he knew of no others involved who were inter- after his client’s arrest that pointed out tens of thousands of warrants were then open. NEWSDAY / J. CONRAD WILLIAMS JR. NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B40 viewed by the district attorney’s investigators. After being told that Mistretta and Capece said they never spoke to any investigator from her office, Rice’s spokesman Coleman Lamb said by email that in fact the Nassau police Internal Affairs Unit had “conducted this investigation” with “oversight” from the district attorney’s office. Though Lamb said that was “standard” practice in such cases, the approach would require extraordinary steps to preserve prosecutors’ ability to bring criminal charges. That’s because internal affairs units focus on violations of department rules and their investigators can use the threat of workplace sanction to compel interviews. Prosecutors, however, must honor the rights of individuals not to incriminate themselves and may not use such interviews to bring criminal charges. In her letter, Rice, who declined to be interviewed for this story, stated that her office had reviewed “compelled departmental interviews” as part of its “consideration of potential criminal charges.” “She should not have received any compelled interviews,” said Jeff Noble, a former Irvine, California, deputy police chief and now a law enforcement consultant who has written extensively on the issue of cooperation between prosecutors and Internal Affairs Unit investigators. “She could not use those interviews in any prosecution and the receipt of the interviews may have tainted her office from being able to conduct an investigation if there was independent evidence of a crime.” Any valid criminal investigation, he said, would have required Rice to Randy White in August 2014. establish a “clean team” of prosecutors, none of whose members had seen the compelled interviews. Asked how Rice expected to investigate potential crimes using internal affairs investigators, Lamb wrote “that’s a more detailed question than we can handle without having access to case files, notes and personnel at the DA’s Office.” Lamb referred a reporter to the office of District Attorney Madeline Singas, who succeeded Rice in 2015. A spokesman for Singas recently declined to provide details of the investigation. In response to a public records request Newsday made to the district attorney’s office, Singas provided portions of the White case file in early 2017, withholding some portions so as not “to reveal confidential information relating to a criminal investigation” and to avoid “unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.” Newsday received White’s fivepage notice of claim against the county in the civil lawsuit that resulted in his $295,000 settlement, 50 pages of related case law research and news stories, Rice’s letter of December 2013 and a two-sentence “final agency determination” from 2015 that found White’s in-custody subpoena service did not “warrant a criminal prosecution.” Newsday has asked Singas’ office how it was able to close that investigation without having interviewed Mistretta, the man who delivered the subpoena, but has gotten no answer. The only other record the office provided in response to the records request was an email from White’s attorney to a prosecutor sent shortly Commissioner, chief of detectives out On Dec. 9, 2013, three days before Rice issued her letter, Dale contacted Capece while he was vacationing in Florida and told him he had to come back to Long Island to be interviewed by internal affairs, Capece said. At the time, Dale was himself presumably a focus for investigators. Capece said Dale told him not to worry because “directly from Kathleen Rice” he’d gotten everything “smoothed out” in regard to her soonto-be-released letter. Rice’s spokesman Lamb denied that such a conversation with Dale took place. “Is there any evidence at all to suggest it did,” Lamb wrote, “other than Mr. Capece claiming that he heard it second hand from Mr. Dale?” The day Rice produced her letter, Dale resigned, under pressure from Mangano. In an interview the following year, Melius called Dale’s ouster “the worst thing in my life.” “It was worse than getting shot for me,” he said, adding that despite Justice Winslow’s decision to the contrary, he believed White had “perjured himself.” The same day the Rice letter was released, Capece said, Mangano called him on speakerphone, saying he had “tragic news.” Mangano told him that he was at fault for the White debacle, Capece said, and that he had a choice: retire or be demoted to sergeant. When Capece responded by saying he needed time to make such a decision, he said, Mangano deputy Rob Walker told him, “You have 15 minutes to make up your mind.” Walker also demanded to know whether he knew that he was obligated to refuse when asked to make an illegal arrest, Capece said. He chose to leave the department. “I don’t want to work for these people,” Capece said he remembers thinking. The failure to bring criminal charges angered Nassau Democratic Party leader Jay Jacobs, who once backed Hardwick in a Freeport mayoral race and recruited Rice to run for district attorney in 2004. Jacobs said he was dismayed by Rice’s decision and aghast at the White affair, calling it “blatant witness intimidation.” Jacobs is not alone in characterizing the episode as criminal. Gershman, the Pace Law School professor and former public corruption prosecutor, reviewed news reports that detailed the episode and said if the case had arrived on his desk, he’d have immediately empaneled a grand jury. “This is just so outrageous,” Gershman said. “Do you have a conspiracy to violate White’s civil rights? Of course you do. Do you have official corruption? Of course you do. You have a lot of crimes here.” B41 PATRICK E. MCCARTHY NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION Nassau County District Attorney Kathleen Rice, seen in June 2010, began an investigation shortly after details of Randy White’s arrest became public. Melius emails District Attorney Rice BY WILL VAN SANT AND PAUL LAROCCO will.vansant@newsday.com paul.larocco@newsday.com NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 into the Randy White case. In a brief interview last August, Melius expressed bitterness at Rice for rejecting their association after having, he said, visited Oheka more than once with what he called “her little rat dog Pearl to eat, drink and be merry, ask me for favors, ask me for money.” Lamb disputed Melius’ characterization of Rice and offered what he called “photographic evidence” that Pearl is a “lovely animal who looks nothing like a rat.” In a December 2009 email, Melius told Rice that Anthony Marano, Nassau’s top judge, wanted to meet her for lunch at Oheka Castle. In the same email, Melius told Rice that Independence Party leader Frank MacKay was eager to set up a dinner. Lamb wrote that he could not say whether the meetings with Marano or MacKay took place, but that Rice had lines of communication with both men newsday.com In emails Gary Melius sent to Kathleen Rice, then the Nassau County district attorney, from December 2009 through June 2013, he tried to arrange play dates for their dogs and sought to set up meetings between her and judges. The nine emails, provided to Newsday in response to a public records request to current District Attorney Madeline Singas’ office, show a cheery Melius, who with his wife and an employee donated $13,300 to Rice’s political campaigns, also passing along the resume of a friend’s son, whom Rice hired. Though the emails suggest a friendly relationship, Rice’s spokesman, Coleman Lamb, said by email that the two were never personally close. “Kathleen never accepted, let alone asked for, favors of any kind from Mr. Melius,” Lamb wrote. The district attorney’s office, in fulfilling Newsday’s records request, found no email responses from Rice to Melius. Lamb wrote that Rice cut off contact with Melius and stopped taking his donations before the Randy White investigation, which began in late 2013. Asked why Rice did so, Lamb wrote that she made the decision in conjunction with the district attorney’s office, but that he was “not privy to the reasoning.” Today, Melius faults Rice for being thankless. In April, he said Rice alone among local politicians distanced herself from him after the 2014 attempt on his life. Rice didn’t seek Independence Party support in her successful run for Congress that year, publicly citing her office’s investigation that were independent of Melius, as would be expected given their roles in the judiciary and politics. In a March 2012 email, Melius suggested that his Labrador retriever, Otto, and Pearl, Rice’s half-Maltese half-Yorkie, needed to get together. “Otto has been asking for Pearl,” he wrote, “so hopefully we can set up a play date again.” In the same email, Melius included the resume of a Bronx prosecutor whom Rice later hired to work in her public corruption bureau. Rice has denied that Melius played any role in hiring the prosecutor, who no longer works in Nassau. “I was wondering if you could spare a little time for lunch or dinner with an old friend,” Melius wrote in a June 2013 email. “How’s Pearl – Otto has been asking for her.” Nine days later, Melius wrote asking whether Rice wanted Thomas Adams, Nassau’s top judge, to join them for a July 9 lunch. The proposed lunch did not take place, Lamb wrote. The White scandal would explode four months later. NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B42 CHAPTER 7 WITH NEW PLAYERS, WILL LI’S ENTRENCHED SYSTEM SURVIVE? BY SANDRA PEDDIE sandra.peddie@newsday.com NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com O heka Castle’s grand ballroom has been home to decades of fundraisers, weddings and parties for Long Island’s elite. In a small, linen-white dining room nearby, intimate networking lunches hosted by the influential Independence Party have drawn a steady stream of judges and law clerks. Down in the basement is what the castle’s proud proprietor, Gary Melius, calls his “man cave,” where some of the Island’s most powerful figures have smoked cigars and traded stories. The castle has stood unrivaled as an expression of power on Long Island, and its bonding rituals provide a blueprint of how local influence operates, bearing fruit for Melius, his allies and many others. Whatever it costs the public, for those in power the system works. The grand tour Melius nearly lost his life in the shadow of his greatest success. From the day he bought the abandoned castle, in 1984, Melius dedicated himself to restoring Oheka. He sold it in 1988 for $22.5 million to a Japanese billionaire accused of negligence in a hotel fire that killed 33 people, and years later bought it back from the businessman’s family for a third of that recorded price. He was cited for ignoring fire safety and zoning laws and fought his neighbors, but after an aggressive political and public relations campaign, he won approval from Huntington officials he had supported to operate the castle as a commercial enterprise. Over the years, he said, he had invested millions renovating the castle, trying to recapture its original look. He transformed what was then a 127-room mansion into an exclusive setting for lavish wedding receptions, the home of a high-end restaurant and boutique hotel, and a mingling ground for Long Island’s political, law enforcement and judicial elite. A night at the hotel can cost more than $1,000, a catered event tens of thousands — up to $500 a head, in addition to a rental fee of up to $12,000. Restaurant guests can sample appetizers like lobster meatballs for $20 or steak entrees for up to $55. The curious can book tours, with prices ranging from $15 to $100, according to Oheka’s website. There’s a lot to see. Start at the main entrance, where the marble steps, wrought-iron railings of the grand staircase, and shimmering crystal chandelier offer an expansive introduction to a mansion where F. Scott Fitzgerald was supposed to have gotten inspiration for Jay Gatsby’s fantasy palace in fictional West Egg, Long Island. These days, it has been used as a location for Taylor Swift’s 2014 “Blank Space” video about a woman living the Gatsby life who unleashes her fury on a cheating beau in, of all places, a castle parking lot. Just outside the castle are the gardens and Great Lawn, where Melius holds an annual Garden Party hosted by Friends of Oheka, a nonprofit formed to raise restoration money and public awareness of the castle. After buying tickets, party guests may rent antique Gatsby-style attire and props, like tommy guns, through an Oheka website. Musicologist Roger Hall, who had lived as a student at the Eastern Military Academy when it was located at Oheka, created a website called “Memories of Oheka.” On it, and in a subsequent interview, he described a 2004 garden party where, he said, Huntington Councilman Mark Cuthbertson played Jay Gatsby. Cuthbertson said he did not remember doing so. The formal gardens, with eight reflecting pools, three fountains and assorted statuary, are also a popular spot for weddings, among them those of the singer Kevin Jonas; Anthony B43 NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION THE NEW YORK TIMES / JAMES ESTRIN Withnewplayers,will LI’sentrenched systemsurvive? of happiness.” The insider’s tour Angela, held their wedding reception in the Terrace Room in 2015, documenting the event in an elaborate video. Chuck Ribando, former Nassau County Executive Edward Mangano’s deputy for public safety, held his daughter’s wedding at Oheka when he was chief investigator for then-Nassau District Attorney Kathleen Rice. For at least some insiders, the payment terms are different from CONTINUES on B44 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 But there’s another tour of Oheka that can be constructed, shaped by the workings of Long Island politics. This is a more private world of cigar parties, man-cave gatherings, power lunches and political and judicial candidate screenings, over which Melius has at times presided, where local players forge relationships and cut deals outside public view. Politically, the result is something in which Oheka has served less as a backdrop than an agent. “Politics is a perception business, and if you can represent yourself as some- Gary Melius plays poker with prominent attorney Steven Schlesinger, to his right, former U.S. Sen. Alfonse D’Amato and others at Oheka Castle in 2007. one who can move votes or move money, or both, you’re powerful,” said Jay Jacobs, the Nassau Democratic leader with whom Melius has had a tumultuous relationship. “Oheka is an imposing, magnificent facility. I liken going to Oheka Castle to in some respects going into the Oval Office.” In this world, it’s not a wedding involving a pop star that catches the eye. It’s weddings of people like Steven Schlesinger. Schlesinger, then counsel to the Nassau Democratic Party, married Caryn Fink, a law clerk, there in March 2014, filling the grand ballroom, restaurant and bar. Assemb. Phil Ramos and his wife, newsday.com Weiner and Huma Abedin in a ceremony officiated by former President Bill Clinton; and the late mob boss John Gotti’s grandson, John Agnello, with his proud mother, Victoria Gotti, looking on. The 23-foot-high Grand Ballroom, lit by crystal and silver wall sconces, dominates the second floor. The sleek bar and restaurant are open to the public, and Melius often stops in to greet guests, on occasion showing them just where in the head he was shot. In the morning, guests can breakfast in the yellow Terrace Room, added to accommodate larger events, or stroll amid the gardens. Oheka, Melius has said, “is a place NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com Anthony Weiner and Huma Abedin at their Oheka Castle wedding in July 2010. what Melius normally charges. In an August 2014 interview, he said he routinely gives discounts to law enforcement personnel and personal friends, including those in politics. He didn’t offer examples. But Schlesinger didn’t pay for his wedding until five months later, a day after a Newsday reporter made inquiries about judicial assignments he and other associates of Melius had received. He produced a $75,000 check as proof of payment. Financial interactions involving Melius and Schlesinger drew the interest of the courts, where an examiner found later that there had been no invoices for the wedding at Oheka and that an internal worksheet listed no money due and contained the word “barter.” The Friday cigar nights, at which a strong law enforcement contingent has mingled with the Island’s elite, have been held in the castle’s courtyards, according to several regular attendees. Mangano dropped in regularly with then-County Sheriff Michael Sposato often driving. Alfonse D’Amato, the former U.S. senator who remains politically involved, has also popped by occasionally. Robert Hart, who headed the Long Island FBI office and has served as a deputy Nassau police commissioner, has attended, as has Malcolm Smith, once the Democratic leader of the State Senate who was convicted on corruption charges involving his would-be New York City mayoral campaign in 2013. Sprinkled through many of the rooms have been several decades of fundraisers for such figures as state Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman, Mangano, Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone, then-Suffolk Legis. Lou D’Amaro, and Steve Levy, then-Suffolk County executive. In an interview, Melius said he had hosted in-kind fundraisers for Levy and D’Amaro, meaning that he donated the cost of the events to their campaigns. Many of those closest to Melius have often been invited to the library for brandy and cigars. State Independence Party leader Frank MacKay, who has posted Oheka photos on his Facebook page, has been one. Mangano has been another. Far removed from the public tour, past the basement bakery and laundry, there’s what Melius calls the man cave, which remained unfinished as the rest of Oheka was reborn, with wooden planks leading to a wall lined with urinals. Melius has one rule for that room: No women allowed — even politicians he’s trying to cultivate. In a March 2012 email to Rice, then the Nassau district attorney, in which he passed along the resume of a good friend’s son, Melius wrote: “Hi, Kathleen, I really enjoyed the other night, lots of laughs. Sorry I couldn’t bring you to the man cave, wink wink — but rules are rules.” That email and other emails provided by the district attorney’s office show no response from Rice, and her office said she made none. The Chaplin Room, where the fuchsia walls are lined with photos and posters of the Little Tramp, is another special place. Although the public can rent it for parties, it outranks even the man cave as a home of political muscleflexing. Beyond the election night gatherings that have drawn former Congressmen Steve Israel and Gary Ackerman, and other top elected officials, the truly special event is the running poker game, where the regulars have included D’Amato, Schlesinger and Dennis Lemke, a prominent criminal defense attorney, others who have attended said. The Chaplin Room also has been used by the Independence Party to screen candidates for office, according to Jacobs, the Nassau Democratic chief. Oheka is the unofficial headquarters of the party, which has drawn enough votes to sway judicial elections in Suffolk and provides a platform for MacKay to negotiate complicated cross-endorsements that can assure a candidate’s victory. “If you’re the Independence Party, your home court is an advantage,” Jacobs said. Melius has been listed as the party’s chief adviser, and he has paid MacKay, the party’s statewide and Suffolk County chief, as a public relations executive at Oheka. In 2016, MacKay earned between $20,000 and $50,000 according to state filings that require party leaders to list outside income in broad ranges. In previous years, he made between $100,000 and $150,000 annually. Oheka also employs Richard Bellando, the party’s Nassau head and Melius’ former son-in-law. A dining room lined with silk murals has hosted what MacKay calls “power networking luncheons,” With those cross-endorsements, Whelan won with the highest vote in the 10th Judicial District. By 2011, his career in full bloom, Whelan was assigned to one of Suffolk’s three commercial courts, where business litigation and foreclosures provide opportunities for coveted judicial appointments for lawyers and property managers to oversee troubled assets. Whelan was also a welcome guest at Oheka and attended the castle’s posh Super Bowl parties, Melius recalled in an interview. In an interview with Newsday editors last year, Melius readily acknowledged Oheka’s popularity, and his. “Everybody comes to me,” he said. “You know why? I deliver if I can. If I can’t, I tell you. I don’t pay anybody off.” Power in action MELIUS FAMILY BARBARA KINNEY NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION B44 Gary Melius in a March 2014 video, speaking publicly for the first time after he was shot three weeks earlier. where he and Melius have brought together Broadway producers, local politicians, law clerks and judges. Judges are prohibited from politicking, so casual gatherings with party leaders offer an opportunity to get known. The connections can be useful. Nowhere is that more evident than in the history of Thomas Whelan, who, while Babylon Town attorney in 1988, drove across the median on the Southern State Parkway and hit an oncoming car, seriously injuring a Commack man. Whelan was charged with seconddegree assault, vehicular assault and driving while intoxicated. He ultimately was convicted of three misdemeanors and a violation and sentenced to probation for 3 years. He was not reappointed by the town when his term expired. It was a setback that could derail a career. But in 2000, Whelan, who is godfather to MacKay’s daughter, saw his career resurrected after MacKay constructed a complex cross-endorsement deal on his behalf. By agreeing to Independence Party backing for Democratic candidates, MacKay persuaded the Democrats to back Whelan for a Suffolk Supreme Court judgeship, party leaders told Newsday at the time. He also secured Conservative and Working Families lines. Oheka’s power hubs intersect freely, particularly over arcane opportunities that only political insiders might recognize. One involved Oheka itself, already the beneficiary of many decisions by the Huntington Town Board that allowed and expanded commercial activity in a residential neighborhood. Many board members frequented the castle, had become Melius’ friends and received generous campaign contributions from him. They credited their decisions with restoring an architectural gem. But those decisions paled in potential impact to one they made in 2012 permitting construction of 191 condos on the property projected to sell for between $1 million and $5 million. The potential value created by their vote could run into the hundreds of millions of dollars. Cuthbertson, a Democratic board member whom other guests recall seeing at annual garden parties at Oheka and who received more than $30,000 in contributions from Melius over the years, opened the way in 2009. He sponsored a resolution establishing cluster zoning of golf courses — including the one next to Oheka. Such zoning allows a developer to build more units than normally permitted in one area of the cluster in exchange for preserving open space in another. Cuthbertson then sponsored the critical 2012 zoning change to allow 191 condominium units on the property, which passed unanimously. Oheka Castle is 109,000 square feet. The proposed condo complex would be 393,427 square feet. At the time, Cuthbertson was engaged with Melius in another lucrative public realm. They and Melius’ daughter, Kelly Melius-DiPreta, were involved in two court-appointed receiverships that earned the three a total of $284,000 in fees and expenses. Cuthbertson did not disclose those ties at the time of the town board’s vote. He said this was because his was a “parallel” relationship in which a judge appointed him and the B45 NEWSDAY / JOHN PARASKEVAS NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION Coveted appointment Schlesinger, meanwhile, has reaped rewards in another judicial sphere and shared them with a charity created by Melius, his Oheka poker pal. He was appointed by the Nassau County Surrogate’s Court to manage a foundation created by Shirley Giten- stein of Atlantic Beach after her death in 2007. The Kermit Gitenstein Foundation, with $11.4 million in assets, financed Jewish causes and health care. This kind of appointment is coveted by politically connected lawyers because foundations created by wealthy individuals who die without heirs need to be managed and their funds distributed. The fees for carrying out these functions can be substantial. Records show Schlesinger earned more than $100,000. Schlesinger gave $250,000 of the Gitenstein money to the Elena Melius Foundation, named for Melius’ mother. The donation came two days before Schlesinger’s wedding. He also provided $50,000 of the Gitenstein Foundation’s money to a charity started by another Oheka poker pal, D’Amato, who spent the money on a water park that was built in his hometown, Island Park. In May 2016, the newly elected Nassau Surrogate’s Court Judge Margaret C. Reilly issued a scathing ruling and removed Schlesinger, calling him “unfit” because he had engaged in potential self-dealing, exceeded his authority as receiver, and had failed to comply with court orders. Edward Mangano, the Nassau County executive, with Gary Melius in 2014. Joseph W. Ryan Jr., appointed by the court to examine the case, found that Schlesinger had allowed Melius to direct where thousands of dollars in grants from the Gitenstein Foundation should go. Reilly said that was a conflict of interest, citing an email to Melius from Schlesinger’s legal assistant that asked him “to list the organizations Gary Melius decided on and the amounts requested . . . I don’t want to miss any.” Both the state attorney general’s office and the Eastern District of the U.S. attorney’s office investigated the transactions. A spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office declined to comment. In a court settlement related to the state attorney general’s office inquiry, Schlesinger agreed to stop taking commissions from the foundation and pay back $150,000 he’d earned as receiver. He was forbidden to serve on a nonprofit or charity for five years. Schlesinger declined to be interviewed for this story. He said in a statement that he had made “no adCONTINUES on B46 NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 Whelan declared that Melius had “the appropriate ethical character” for the post. Whelan’s lawyer, Clifford Robert of Uniondale, said in a statement that the judge, who was subsequently transferred out of the commercial part, had “proudly upheld the highest standards of both the practice of law and of the judiciary.” Cuthbertson, who was paid $101,594 for his role in the Islandia building, said in an interview that he had recommended Melius’ daughter as manager for a subsequent receivership, because he thought she was well qualified. Altogether, Melius and friends and allies collected more than $750,000 in fees from four receiverships. Among those allies were his former son-inlaw, Bellando; his lawyer, Ronald Rosenberg, and Schlesinger, court records show. newsday.com Meliuses separately, although he did acknowledge that he had recommended Melius-DiPreta for her assignment. The town ethics board, whose members are appointed by the town board, later found that he committed no “technical ethical violation,” but said Cuthbertson should disclose such appointments in the future. The judge in both receiverships was Whelan. When he was assigned the case of a foreclosed medical building in Islandia in 2008, Whelan named Cuthbertson to the role of receiver, the person who manages a building’s finances and overall operation. Whelan chose Melius to run the building day-to-day as property manager. He was not on an approved list of professionals established by the courts after repeated scandals involving judicial appointments of donors and cronies. Because Melius was not on the list, court rules required Whelan to write a finding “of good cause” to appoint him. In similar instances, other judges have cited a person’s particular expertise with an unusual type of property, like a horse farm. The Islandia property is an office building. B46 NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION mission of wrongdoing.” His spokesman, Gary Lewi, has said Schlesinger “discharged his fiduciary duty appropriately.” Melius has strongly denied any wrongdoing. Partnership deteriorates Other deals involving Melius imploded because of friction between him and his partners. One involved an engineer, John Ruocco, who created a company, Interceptor Ignition Interlocks, that produced a device to prevent people convicted of drunken driving from starting their cars if inebriated. To get an edge on the competition in the market, court records show, he gave Melius nearly 3 million shares of stock in return for help in getting Nassau and Suffolk to enact regulations that mandated use of technology employed by his company. Melius reached out to his contacts, including D’Amaro, the Suffolk legislator for whom he sponsored an Oheka fundraiser, and the Mangano administration. Both counties approved regulations that favored the company’s technology, and Interceptor’s market share soared. Interceptor’s market share went from 7 percent to 54 percent in Nassau. In Suffolk, the company’s market share increased from 13 percent to 22 percent. But the partnership deteriorated. Melius sued Ruocco, and, with the approval of both sides, the case was decided by Whelan. He issued a ruling that gave Melius control of the company’s stock. A New York State appeals court eventually reversed Whelan’s decision, saying that he had failed to hold a jury trial, as Ruocco had requested, and thus should not have granted summary judgment in favor of Melius. Ruocco has said he hopes he can revive the company. Prior to the appeals court decision in December 2016, Melius had struggled to put Interceptor completely under his control. At the first board meeting after Whelan’s decision, on Feb. 21, 2014, Melius added one ally to the board but was unable to gain a majority. Three days later, Melius was shot. NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 newsday.com A shooting unfolds The grainy video lasts all of 49 seconds. It starts with Gary Melius in a dark winter jacket striding on a diagonal from the lower right of the frame across the rear parking lot of Oheka Castle. After about 12 seconds, he reaches the driver’s side of his black Mercedes and lowers himself in. As he does, a dark sedan leaves the lot. It circles behind him, slows briefly and pulls out of the frame. Eighteen seconds later, a tall man wearing a winter jacket becomes visible getting out of an SUV at the far left of the frame, hunching a bit and moving quickly as he snakes among three cars to reach the driver’s side of the Mercedes. Only the back of his head is visible as he fires the shot that strikes Melius in the left temple. He remains there two and a half seconds. The gunman then hustles away, crouching at two points looking toward his hands and then back at the car, as a worker emerges from behind a building at the parking lot’s edge. Next, the shooter vanishes, about 13 seconds after he first appeared. He remains unidentified to this day. After the shooting, detectives sought the names of Melius’ adversaries, trying to determine who might have a motive for doing him harm. They knocked on a lot of doors, including that of Ruocco, whose former lawyer said he is not a suspect in the case. “Simply put, there are so many suspects,” a law enforcement official who has been briefed on the investigation said in 2017. Another law enforcement source with direct knowledge of the case said it quickly became clear that Melius “was connected to everybody” and that the list of potential suspects grew to more than 60 people. Russian mobsters were caught on tape chuckling about the shooting, according to a law enforcement source, but that lead went nowhere. In the interview with Newsday editors, Melius voiced suspicions about a restaurateur, but nothing has surfaced about that, either. Melius’ friends and family offered a $100,000 reward and hired a billboard truck, which was briefly parked in a Newsday lot to announce it. But an official involved in the case said that when questioned, Melius had given leads to detectives that did not prove fruitful. Melius said he has cooperated fully with police. But he may have hinted at tensions with law enforcement authorities’ handling of the investigation in a comment to Newsday reporters several months after the shooting about the prosecutor heading the investigation, Nancy Clifford. “If I don’t like her, I won’t tell you,” he said. He blamed the police department and Suffolk District Attorney Thomas Spota for failing to solve the shooting in the interview with Newsday editors. Spota was indicted last year for allegedly obstructing a federal investigation into the beating of a prisoner by former Suffolk Police Chief James Burke and its cover-up. “I think the PD screwed up, Tommy Spota screwed up by not putting out the picture of that car,” Melius said, referring to the fact that the Suffolk Police Department released the video two years after the shooting. A spokesman for Spota said last year that it is standard procedure not to release such videos in an ongoing investigation. The police department declined to respond to requests for comment. Burke, the police chief who headed the shooting investigation, went to federal prison in 2017 for his assault of a suspect in 2012. Spota, Burke’s longtime mentor, and one of his chief aides were indicted in October 2017, accused of being involved in covering up the assault. Spota retired in November, maintaining his innocence. The fallout Since the shooting, FBI agents have carted away boxes of material from Oheka. Melius said the agents had found nothing incriminating. “The FBI came to me and they wanted my stuff and I gave them 180 boxes of stuff,” he said. “And you know how many I had my lawyer look at? None. I have nothing to hide. I gave them everything.” Melius said his life has fallen apart, as well. He can’t drive because he suffers seizures, and he can no longer enjoy a bourbon or a cigar, he told Newsday editors. His wry conclusion: “I will never do that again, getting shot in the head.” Oheka is also hurting. It had a net operating income of $2.38 million in 2014, according to Bloomberg’s financial data. That fell to $1.82 million in 2015 and $742,577 a year later. In July 2015, Melius’ mortgage company, LNR Property LLC of Miami Beach, noted that Oheka required “substantive repairs” and needed a monthly budget of $72,455 for maintenance. In December 2015, he stopped making mortgage payments, according to Trepp LLC, a Manhattan property data company. He was hit with a foreclosure lawsuit that continues. As of January, he owed $26 million on B47 NEWSDAY / JOHN PARASKEVAS NEWSDAY INVESTIGATION At times like these, the cozy network of Long Island politics has been Melius’ reliable safety net. In mid-August, as the battered Mangano administration faced its last months in office, it placed an item on the Nassau Legislature’s agenda that would allow Melius to connect Oheka, which is close to the NassauSuffolk border, to Nassau’s sewage dates to succeed Mangano immediately voiced skepticism. Melius told a reporter in October that he would not comment because the Newsday news article on the sewer hookup had “cost me millions.” A new leader has taken the helm in Nassau, with Laura Curran, a Democrat, as the new county executive. In Suffolk, upstart Democrat Timothy Sini has taken over the district attorney’s job. They have promised to restore integrity to government. But in an election season imbued with the drumbeat of reform, there were quieter lessons about the resilience of machine politics. In Suffolk, the Democrat, Errol Toulon Jr., defeated a Republican in the county sheriff’s race with Conservative and Independence Party sup- Gary Melius at Cold Spring Country Club in 2009, with his neighboring Oheka Castle in the background. port, which provided the margin of victory. Sini won after a similar cross-endorsement deal. Curran celebrated her victory at a news conference in which she stood next to Nassau’s Democratic leader, Jacobs. Melius, now 73, with many friends fading from the scene or already gone but others holding fast, finds himself again in a place both precarious and familiar — facing seemingly tough odds on the playing field of Long Island politics. The question is whether the rules of the game have changed, or whether they easily can be. NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER ● NEWSDAY, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2018 Facing tough odds system — quite literally the last link needed to fully realize a vision of Oheka he has harbored since 1984. The hookup would handle a projected 156,000 gallons of wastewater a day from the condos Melius won approval to build in 2012. The proposed agreement called for Melius to pay $425,000 to connect to the Nassau system, as well as $23,000 for a sewer permit. For a proposed development across the street from Oheka, the figures are strikingly different. It would pay more than twice as much for fewer than half the units and less than a third of the projected wastewater. When news of the proposal emerged, the item was yanked from the agenda and, in an anti-corruptionthemed campaign season, both candi- newsday.com Oheka’s two mortgages. “I am not sitting up there counting bills and money,” he said. “I don’t have it. I’m fighting for my life.” The long shadow Oheka casts over local politics seems to have grown a little shorter, too. Meetings with party leaders, other than MacKay, have diminished, by many accounts. ● ELLIOTT KAUFMAN NEWSDAY COM/PATHWAYTOPOWER