Unison MIDI Chord Pack Guide: Chords & Progressions

advertisement

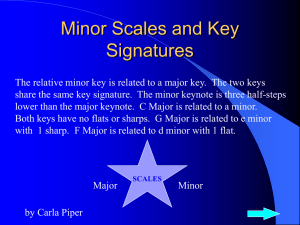

Introduction: Thank you for purchasing the Unison MIDI Chord Pack. Many people find the topic of chord construction and chord progressions quite confusing and technical. Some common questions are: “What is a chord?” “Which chords sound good together?” “What are some time-tested chord progressions?” “How do I move beyond the basics into more complex and emotional sounds?” This chord pack will answer these questions as well as provide you with hundreds of chords and chord progressions that you can drop into your own tracks, instantly creating a professional sound. If you don’t care much about the hows and whys, feel free to dive into the pack and start dropping some MIDI files into your DAW. Just load up your favorite virtual instrument and start experimenting. On the other hand, if you’d like a more in-depth guide to this pack and chords in general, read on! Structure: Folder structure in this pack: Musical Key ● Triads ● Extended Chords ● Borrowed Chords ● Progressions ○ Diatonic Triads ○ Advanced Progressions Musical Key: In this pack, we have created separate folders for each of the 12 keys used in western music. The keys will allow you to either create songs from scratch in whichever key you choose or find new chords and progressions that will complement a track you are already working on (provided you know the key of the track!). A key, in the musical sense, is a collection of notes that we can draw from to create the chords, melodies and bass lines that make up a song. In almost every case, a key will also have a center—a note that feels at rest or settled. The other notes of the key are derived from this root note by use of a scale formula. For this guide, the terms “scale” and “key” will be used interchangeably. In Western music, we rely on two specific scale types to a large degree. The first is called Major, which is bright or uplifting in its emotional quality, and the second is called Minor, which is darker, more melancholy or tense. Here are the scale formulas that allow us to create these patterns of notes: Major: R + W + W + H + W + W + W Minor: R + W + H + W + W + H + W Here, R stands for “root note”, which will be the note by which we name the scale (like C Major, G Minor or Db Major), the home note of the key. W = Whole Step (distance from C to D) H = Half Step (distance from C to Db) To build a scale using a formula, simply choose whichever root note you want to start with, plug it into the R value in the formula and begin adding whole steps and half steps as the formula indicates, taking each new note you arrive at as the next note in the key. We will build G Major: Major: R +W+W+H+W+W+W G A B C D E F# You will notice that each folder in this pack is labelled with one major key and one minor key, such as: 1 - C Major / A Minor This is because every major key has a minor key that is relative to it. Relative, in this sense, means that it uses the same set of notes. Using the scale formulas shown above, we can construct the following two scales and compare them: C Major: C-D-E-F-G-A-B A Minor: A-B-C-D-E-F-G Notice that both keys contain the same notes, they just begin in different places. What this means for us is that the keys of C major and A minor (or any other pair of relative keys) consist of the same set of chords as well, which is why they share one folder in this pack. The difference between any major scale and its relative minor (or vice versa) is where we sense the tonal center of the key to be, or, in other words, which chord feels like home—the point of greatest rest in the key. To specify this, we use a system of chord analysis utilizing Roman numerals to denote which chord is the tonal center. Roman numeral analysis is standard practice in all styles of Western music and makes looking at, speaking about and thinking of chords and chord progressions much simpler. Major Keys I ii iii IV V vi vii C D E F G A B Maj min min Maj Maj min dim Capital Roman numerals refer to major chords and lowercase numerals refer to minor chords. The pattern or order of major chords and minor chords in the table is the same for every possible Major Key. A chord progression that goes: Cmaj - Gmaj - Amin - Fmaj Could be more simply notated as: I - V - vi - IV This is the way you will find chords and chord progressions notated in this chord pack. Minor Keys i ii III iv v VI VII A B C D E F G min dim Maj min min Maj Maj When dealing with minor keys there is a new order of chords due to now, in this case, calling Amin the home chord. Looking carefully, we can see that this new order of chords is actually the same order found in major scales, only the starting point has changed from C to A. This change is important because it keeps our notation of the progression consistent with how it sounds in actual practice. In the key of A minor, Cmaj no longer feels like home. You may have noticed a chord labelled ‘dim’ in the tables above. This stands for ‘diminished,' which is a type of chord — a strange, scary or odd sounding chord that is hardly ever used in modern music genres except jazz and film scoring. For this reason, to give you the most amount of truly usable chords, we have replaced the diminished chord of each key with a variation that will flow much better. You can trust us on this! What exactly is a chord? A chord is simply a collection of 3 or more notes played simultaneously. The notes of a chord are derived from a major scale according to a chord formula. For instance, here are the chord formulas for m ajor and minor chords: Major = 1 - 3 - 5 Minor = 1 - b3 - 5 Here, the numbers are referring to degrees (note numbers) of a major scale. For a C maj chord, we take the first, third and fifth notes of the C Major scale and play them all at once. For a C min c hord, we take the first, flatted third, and fifth notes of a C Major s cale. Referencing the table above that shows the notes of C Major, we get these notes for each chord: Cmaj = C - E - G Cmin = C - Eb - G Playing either of these note groupings will produce the corresponding chord. It is important to note here that the only difference between a major chord and a minor chord, based on the same root note, is that the minor chord has a l owered third. There are formulas for every chord type imaginable. You can find a list of some of the most important chord types at the end of this guide. Triads: In music speak, a triad is the most basic kind of chord. Triads consist of 3 notes and come in 4 varieties: Major Minor Diminished Augmented In this chord pack, we will only be dealing with major and minor chords for the most part, though some diminished and augmented chords can be found in the ‘Advanced Progressions’ folders for each key. All we need to know at this point is that major chords have a more positive, light feel to them, whereas minor chords are darker or more serious sounding. A chord progression that contains lots of major chords (uppercase Roman numerals) will have a positive vibe, and the opposite will be true for progressions that feature mostly minor chords (lowercase Roman numerals). Just because triads are the most basic kind of chord does not mean they are lame or not as good as more complicated chords. The majority of the world’s most popular songs have consisted of nothing but triads because of the way in which they convey emotion powerfully and directly. Take a listen to some of the triad chords and chord progressions and see what you think. The choice of whether to use triads or extended chords should stem from your personal taste. In each triad folder, you will find 2 subfolders (one major key and one minor key) containing 8 MIDI files each: 7 chords (one for each note of the scale) and one file that contains all 7 for ease of use. These chords have been thoughtfully arranged to play nice with each other so feel free to experiment by putting them in different orders. Extended Chords: This category encompasses all chord types that contain more than three notes with a maximum of 7 (an entire scale played simultaneously). When we speak of a chord having a certain number of notes, this is referring to the number of distinct letter names in the chord, not the actual number of keys being played. Here is an example: Cmaj7: C-E-G-B This chord contains four separate letter names, making it a four note chord. However, we could create a voicing (arrangement of notes) where each letter name appears two or more times in various octaves of the keyboard. Imagine a 60-piece orchestra playing this chord; there are many instruments in many different octaves, but each instrument is playing one of those four notes. If any one of those 60 players played a note other than C, E, G or B, we would have to give the chord a new name because it would now be a five note chord. Extended chords have a complexity or richness to their sound that is not possible using triads because there are now more notes interacting with one another. The number of different types of extended chords is essentially infinite, and so we will not get into an explanation of the various kinds in this guide. Suffice it to say, if you are looking for a jazzy, complex or more sophisticated sound, extended chords are what you want. In each folder of extended chords, you will find a number of different extended variations for each note of the scale. Here is an example with C major: Cmaj6/9 Cmaj7sus2 Cmaj9 CmajAdd9 These chords are essentially interchangeable. You can try out each variation to see which best fits the sound you are going for. You could even use a different version each time the chord progression repeats! Borrowed Chords: So far, all the chords listed have been created using only the notes of the selected key, but this isn’t always the case. It is possible (and in fact very common) to use chords that are built from notes found in other keys in our progressions to spice up the sound, adding interest via unexpected notes. In this pack, we refer to these chords as “borrowed chords” and have given them their own folder within each key. These borrowed chords range from simple alternatives to spine-tingling, exotic sounds that, when used sparingly, can provide moments of heightened emotion, drama or impact. Like with anything in life, it is important not to overuse these chords within our tracks because they will begin to lose their meaning and impact. Similarly, bass frequencies have the greatest impact when they are separated by open space, creating a relationship of tension and release. If we have heavy bass with no gaps or space throughout our entire track, it will become meaningless and lose its appeal. When using strongly coloured borrowed chords, it is best to find opportune spots to place them that will increase their impact. For borrowed chords that are more simple, we can use them more often in our progressions without fatiguing the sound. You will notice that some of the chords in this folder are built on flattened scale degrees (i.e. bII or bVII). When using borrowed chords, it becomes possible to utilize all 12 notes of the chromatic scale as root notes for chords, vastly expanding the possibilities for interesting bass lines and melodies. Progressions: Diatonic Triads This folder contains 24 chord progressions (12 major and 12 minor) that utilize the diatonic triads of whatever key you have chosen. The word ‘diatonic’ means only using notes that come from that specific key. Diatonic chords are those chords that are created using only the seven notes of a specific key. Chords that use notes outside of the key are called ‘non-diatonic.' Very clever! Sometimes, in the Advanced Progressions, borrowed chords will be used in combination with diatonic chords. The chord progressions in these folders have been reworked for each specific key to ensure that they sound as best as they can, playing within a certain range notes that give the greatest impact. This is because certain intervals (an interval is the distance between two notes) within a chord will become unusable when played too low (sound becomes muddy) or too high (sound becomes too thin or brittle). Progressions: Advanced Progressions This folder also contains 24 progressions separated into major and minor. As was hinted at above, these progressions contain all sorts of crazy chords. Because of this, these progressions can add a certain spice or vibe to your productions that bend the ear in new directions. Explore and experiment with these, and you will discover some cool sounds—some that may even challenge your ear and broaden its musical horizons. Like the triad progressions, these advanced progressions have been formatted specifically for each key so they can maintain their intended effect. How To Best Use This Pack: The purpose of this pack is to get your productions sounding the way you want regarding chords. Many tracks are built around chord progressions, upon which melodies lay and underneath which bass lines move. The exact chords and rhythms they move with play a large part of the emotional vibe your track will have, so it is essential to spend some energy in this area. A lot of energy has been spent for you already in the creation of this pack so that your process of music creation can be quicker and flow better. There are three main ways to utilize the contents of this pack: Using chord progressions: The easiest way to get up and running is to browse through some of the chord progressions, in whichever key you feel like working with. Then use one or more of those as a foundation for your track. All chord progressions in a given key will work together so you can create different progressions for different sections of your track quickly. Beyond that, you can take chord progressions and rearrange the chords within them to create new variations of your own. Building your own progressions: Using the individual chord MIDI files found in the ‘Triads,' ‘Extended Chords’ and ‘Borrowed Chords’ folders in each key, you can piece together your own progressions. The approach here can range from a random method — where you grab a few chords at random and start trying them out in various combinations — to a more calculated approach where you may already have a bassline, and you start choosing your chords based on the bass notes already in place. When building your progressions, it may sometimes be worthwhile to rearrange the order of notes in the particular chord you have chosen—this is creating a new voicing of the same chord. To do this, simply leave the lowest note of the chord where it is and then begin raising or lowering the other notes by one octave. For example, if the top note in a certain chord sounds too high for the rest of the progression, just pull that note down one octave into the middle of the other notes. Doing this will retain the same chord type and emotional feeling but may create a smoother progression according to each specific circumstance. If you move a note by more or less than an octave, you may change the chord quality altogether (which could be nice!). It is worth mentioning here that chords will, more often than not, have their root note (the note by which you name the chord, i.e. C major or F # minor) as the lowest tone in the chord, the bass note. So if I’m playing an A minor chord, the bass will probably play an A. This method will give the greatest strength to the chord voicing. However, you can also place one of the other notes in the chord as the lowest note of a chord — this is called an inversion. An example would be to play an A minor chord again but to have the bass instrument play a C note or an E note. Amin = A-C-E This chord would now be written as ‘Am/C’ (read “A minor o ver C). You will see some examples of these inversions in the chord pack, most often on the V II in major keys or ii in minor. Studying the progressions: IIf you’re interested in understanding chords and chord progressions better, you now have a resource of many interesting progressions to study. By looking at the Roman numerals in the name of each progression, you can find progressions that you like and then analyze the chords to see which ones are being used. You can then use those chords yourself when you create your own progressions from scratch. There is a lot of value to be found here. Rhythm: It has often been said by many incredible musicians across all genres that if there is one element of music that is the most important, it’s rhythm. Upon dropping some of the MIDI files from this pack into a MIDI track in your DAW, you will discover that each chord (both individually and in the progressions) is held for one bar. The only reason for this is ease of use. It would be quite boring to leave the chords held statically for one bar unless you are playing the chord through an interesting or evolving sound, so we will now look at how to create rhythms from these MIDI files. This is a screenshot of Advanced Progression #1 in the key of C major as it appears in my DAW (Digital Performer 9). If you have some experience in working with MIDI, this should look somewhat familiar to you. We have the piano roll (keyboard laid vertically) along the left-hand side, the bars 1-4 along the top, and the yellow blocks are the actual notes of the chords lasting one bar in length each. This is roughly how the MIDI files should look for you when you view them in your DAW. I will now show a few examples of rhythmic ideas. To do this, I will simply use my scissor/knife tool to split the chords into smaller chunks and move them around (see below): This is the most basic method of creating rhythms from the chords. As you can see, each chord has been chopped and moved around to different eighth note subdivisions within the bar. This can be done by ear while the 4 bars loop around until you are satisfied with the rhythm you create. In this example, I have separated the root note (lowest note in the chord) from the rest of the chord and created a sort of reggae vibe where the root notes are on the beat, and the top part of the chord is on the off beat. Now the chords change earlier than they have been in past examples. The 2nd and 4th chords appear midway through the 1st and 3rd bars respectively. This is to show that you do not need to keep the chords changing at the same rate they do in the MIDI file. Sometimes changing chords before the bar creates a more interesting rhythmic feel. In this final example, the chords are back to changing once per bar, but the notes are now broken up and played one at a time. When chords are played note by note in this way, it is called an arpeggio. Your synthesizer may have an arpeggiator built into it which would allow you to make all kinds of wild patterns by just feeding in the MIDI file the way it comes originally, with all notes being held for the entire bar. Final Words: By now you should be ready to start creating tunes using these MIDI files. Experiment like crazy; drag and drop all over, combine chord progressions with single chords, change the order within a progression, link multiple progressions together, etc. Just try anything that comes to mind. Some of the best music is made through random experimentation, and the more you mess with the files given here, the more you will feel you have created something truly original. Luckily, even if all you ever did was drop in these progressions and leave them exactly as is, simply applying a new sound, a new rhythm or any other subtle change will create a sense of something fresh. Many of these progressions (and certainly all of the individual chords) have been used and reused by masters of music for decades. Why? Because they are effective! Well chosen chords can take a track to a new level, inspire creativity and ultimately assist in creating music that is enjoyable to listen to. You have the ability to make the kind of music you want to make and using tools like this chord pack can streamline the process. Have fun! Appendix A: Chord Formulas Below is a modest list of the most common chord varieties. They have been separated into the categories of Major (natural third and seventh), Minor (flatted third and seventh), Dominant (natural third, flatted seventh) and Other (common chords that don’t neatly fit in other conceptual boxes). Using this table you should be able to decode the notes of most chords you will encounter when browsing the internet, theory books, jazz charts and so on. Numbers in brackets (i.e. #11) denote altered tones—scale degrees that have been changed from their usual state. Major Types Maj: 1 - 3 - 5 Maj6: 1 - 3 - 5 - 6 Maj7: 1-3-5-7 MajAdd9: 1 - 3 - 5 - 9 Maj6/9: 1 - 3 - 5 - 6 - 9 Maj9: 1-3-5-7-9 Maj9(#11): 1 - 3 - 5 - 7 - 9 - #11 Maj13: 1 - 3 - 5 - 7 - 9 - 13 Dominant Types 7: 7sus4: 9: 9sus4: 13: 7(#5): 7(#9): 9(#11): 1 - 3 - 5 - b7 1 - 4 - 5 - b7 1 - 3 - 5 - b7 - 9 1 - 4 - 5 - b7 - 9 1 - 3 - 5 - b7 - 9 - 13 1 - 3 - #5 - 7 1 - 3 - 5 - b7 - #9 1 - 3 - 5 - b7 - 9 - #11 Minor Types Min: Min6: Min7: MinAdd9: Min6/9: Min9: Min11: Min13: 1 - b3 - 5 1 - b3 - 5 - 6 1 - b3 - 5 - b7 1 - b3 - 5 - 9 1 - b3 - 5 - 6 - 9 1 - b3 - 5 - b7 - 9 1 - b3 - 5 - b7 - 9 - 11 1 - b3 - 5 - b7 - 9 - 13 Other Types Sus2: 1 - 2 - 5 Sus4: 1 - 4 - 5 Maj(#4): 1 - 3 - #4 - 5 Aug: 1 - 3 - #5 Dim: 1 - b3 - b5 Dim7: 1 - b3 - b5 - 6 Min7(b5): 1 - b3 - b5 - b7 MinMaj7: 1 - b3 - 5 - 7