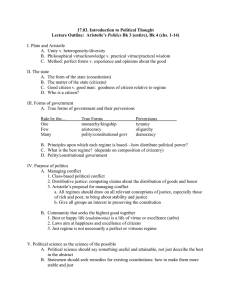

Red Tape, Red Flags: Regulation for the Innovation Age The 2007 CIBC Scholar-in-residence Program by G. Bruce Doern Foreword by Allan Gregg The Conference Board of Canada • Ottawa, Ontario • 2007 ©2007 The Conference Board of Canada* All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-0-88763-793-3 ISBN-10: 0-88763-793-0 Agreement No. 40063028 *Incorporated as AERIC Inc. The Conference Board of Canada 255 Smyth Road, Ottawa ON K1H 8M7 Canada Inquiries: 1-877-711-2262 www.conferenceboard.ca Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Doern, G. Bruce, 1942– Red Tape, Red Flags : Regulation for the Innovation Age : the 2007 CIBC Scholar-in-Residence Program / by G. Bruce Doern ; foreword by Allan Gregg. ISBN 978-0-88763-793-3 1. Delegated legislation – Canada. 2. Administrative procedure – Canada. 3. Administrative agencies – Canada. 4. Risk management – Government policy – Canada. 5. Trade regulation – Canada. 6. Industrial policy – Canada. I. Conference Board of Canada. II. Title. KE5019 D63 2007 KF5411.D63 2007 342.71’066 C2007-905722-5 Printed and bound in Canada by Tri-Graphic Printing Limited. Cover design, page design and layout by Scott Grimes, The Conference Board of Canada. Cover illustration and design by Robyn Bragg, The Conference Board of Canada. CIBC logo is a trademark of Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. Author’s Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to Anne Golden and her colleagues at the Conference Board for the opportunity to be the CIBC Scholar-inResidence and to complete the research for this book. It has been a great pleasure to interact with, and learn from, Conference Board staff and experts in several of the areas linked to this project. Special thanks are owed to Gilles Rhéaume, Michael Bloom, Natalie Brender and others who offered always-constructive comments and editorial advice on earlier drafts. So, too, did my colleagues at Carleton University’s School of Public Policy and at the Politics Department of the University of Exeter. Thanks are also owed to officials and other stakeholder experts who helped with interviews and advice in the three case-study areas examined here. All these very supportive colleagues helped to make this a better final product. Any remaining gaps or weaknesses in the analysis are mine alone. iii Acknowledgements The Conference Board of Canada is deeply grateful to CIBC for its farsighted investment in the Scholar-in-Residence Program, which made this volume possible and will support eight more years of cutting-edge research into topics of vital importance to Canada’s future. We thank our media partner, The Ottawa Citizen, for publicizing the May 2007 lecture that resulted in this volume and for giving Canadians an advance look at the arguments presented here. At the Conference Board, Michael Bloom, Gilles Rhéaume and Natalie Brender organized the 2006–07 Scholar-in-Residence Program, and Natalie Brender edited this volume. And, of course, we thank G. Bruce Doern, as well as Elizabeth May, Janet Yale, Rick Thorpe and Allan Gregg for the splendid contributions to Canadian public debate that they have made. About The Conference Board of Canada We are: A not-for-profit Canadian organization that takes a business-like approach to its operations. Objective and non-partisan. We do not lobby for specific interests. Funded exclusively through the fees we charge for services to the private and public sectors. Experts in running conferences but also at conducting, publishing and disseminating research, helping people network, developing individual leadership skills, and building organizational capacity. Specialists in economic trends, as well as organizational perform- ance and public policy issues. Not a government department or agency, although we are often hired to provide services for all levels of government. Independent from, but affiliated with, The Conference Board, Inc. of New York, which serves nearly 2,000 companies in 60 nations and has offices in Brussels and Hong Kong. vii The Author G. Bruce Doern is well known for his broad knowledge of Canadian and comparative public policy and governance. He is the editor of How Ottawa Spends, Carleton University’s annual review publication on national priorities and public spending. He is director of the Carleton Research Unit on Innovation, Science and Environment (CRUISE). His current research focuses on science-based regulatory and research institutions; universities in the innovation economy; competition policy; energy and environment policy; and intellectual property institutions. The author of over 55 books, Professor Doern has been a faculty member at Carleton’s School of Public Policy and Administration since 1968 and also holds a chair in Public Policy, Politics Department, University of Exeter, United Kingdom. ix The Commentators Allan R. Gregg, Chair, The Strategic Counsel Allan Gregg is one of Canada’s most recognized and respected senior research professionals and social commentators. He has an intimate knowledge of the dynamics of policy making, as well as a deep understanding of cultural change and the communications processes necessary to forge a public consensus around government initiatives. As one of the co-founders of The Strategic Counsel, he is a pioneer in the integration of consulting, public opinion research, public affairs and communications. Mr. Gregg appears regularly on CTV’s Question Period and is the host of TVO’s highly respected talk show Allan Gregg in Conversation. Elizabeth May, Leader, Green Party of Canada Elizabeth May is an environmentalist, writer, activist and lawyer. Active in the environmental movement since 1970, she has undertaken extensive volunteer work on energy policy issues, primarily opposing nuclear energy. In 1986, Ms. May became senior policy advisor to then-federal environment minister Tom McMillan. She was instrumental in the creation of several national parks. In 1989, she became executive director of the Sierra Club of Canada, where she led several successful campaigns (including initiatives to protect vast areas of Canadian wilderness, to promote bylaws against the use of dangerous pesticides and to act on the threat of climate change). In March 2006, Ms. May stepped down as executive director of the Sierra Club of Canada to launch her successful bid for the leadership of the Green Party of Canada. The Honourable Rick Thorpe, British Columbia Minister of Small Business and Revenue, and Minister Responsible for Regulatory Reform Rick Thorpe was appointed minister of small business and revenue, and minister responsible for regulatory reform, in the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia on June 16, 2005. He previously served as minister of provincial revenue and as minister of competition, science and enterprise. Mr. Thorpe earlier served as official opposition critic for small business, tourism and culture. Before his election to the Legislative Assembly, Mr. Thorpe worked in the Canadian brewing industry for 22 years in a variety of senior management positions, in Canada and internationally. He was first elected in 1996 to represent the riding of Okanagan– Penticton and was re-elected in 2001 and again in 2005 to represent Okanagan–Westside. Janet Yale, Executive Vice-President, Government and Regulatory Affairs, TELUS Communications Company Janet Yale is a senior business executive with TELUS, Canada’s secondlargest telecommunications carrier. She is responsible for the development and delivery of key strategies in the areas of public policy, law, regulation, government relations and corporate communications. Before joining TELUS, Ms. Yale was president of the Canadian Cable Television Association. With more than 20 years of government and regulatory experience, Ms. Yale has held senior leadership positions at AT&T Canada, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, and the Consumers’ Association of Canada. xi Table of Contents Preface by Anne Golden 1 Foreword by Allan Gregg 5 Introduction 13 The Three Central Arguments 16 Key Definitions and Conceptual Issues 18 Structure and Preview of the Framework 21 Chapter 1—Key Forces for Regulatory Change and the Current Regulatory Policy Context 27 The Three Key Forces for Change 29 The Increased Speed and Complexity of Underlying Economic and Technological Change 29 Consumer Demands for Faster Access to New Products 31 The Complex, Science-Based Nature of Risk–Benefit Regulation 33 The Relationship Between Regulation and Innovation 34 Regulatory Policies and Reform: The Limits of the One Regulation at a Time and Periodic Regulatory Reform Approaches 36 Current Federal Regulatory Policy and Decision Processes 37 Periodic Regulatory Reform Initiatives 41 Conclusion 47 xiii Chapter 2—The Pharmaceutical Drugs–Public Health Regulatory Regime: Access and the Common Drug Review 49 The Regulatory Regime: Core Features 51 Context, Regime Change and Evolving Criticism 56 The Thalidomide Model and the Pre-Market Safety Focus 56 The Backlog Problem and Slow Product Approval Times 57 Higher Volumes of Drugs, New Levels of Access, and the Rebalancing of Pre- and Post-Market Review 58 Health Canada’s Blueprint for Renewal in an Innovation Context 62 Illustrative Regime Change: The CDR, Access and the Drug– Public Health Regulatory Regime 64 Conclusion 72 Chapter 3—The Biotechnology–Intellectual Property Regulatory Regime: Access to Genetic Diagnostic Tests 75 The Regulatory Regime: Core Features 78 Intellectual Property Aspects of the Regime 79 Biotechnology Aspects of the Regime 82 Context, Regime Change and Evolving Criticism 83 IP and Biotechnology in Innovation Agendas 84 Industry Pressure and Fast-Changing Biotechnology Industry Dynamics 86 IP Rights, Public Health and Global Access to Patented Life-Saving Drugs 88 Illustrative Regime Change: Patented Genetic Diagnostic Tests and the Biotechnology–Intellectual Property Regulatory Regime 90 Conclusion 97 xiv Chapter 4—The Energy–Environment Regulatory Regime: Environmental Assessment of Energy Projects 101 The Regulatory Regime: Core Features 104 Context, Regime Change and Evolving Criticism 109 Energy Industries, Project Approvals and Incentive-Based Regulatory Flexibility 109 The Internalization of Environmental Costs in Energy Prices 113 Sustainable Development as a Policy–Regulatory Paradigm 115 The Climate Change Debate and Policy–Regulatory Failure 116 Alternative Renewable Energy Sources and Regulatory Push 120 Illustrative Regime Change: Environmental Assessment and Energy Projects 122 Conclusion 128 Chapter 5—Federal Regulatory Policy: An Annual Regulatory Agenda and Related Institutional Reform 131 What Is Wrong With the Current Approach to Regulation? The Basic Case for an Annual Regulatory Agenda 135 To What Extent Does Regulatory Agenda Setting Occur Now? 139 A More Complete Regulatory Agenda and Agenda-Setting Process: What Would They Look Like? 142 Related Institutional Reform: A Regulatory and Risk Review Commission 146 Conclusion 148 xv Chapter 6—Conclusion 151 Red Tape, Red Flags: Complex Interactions, Integration and Role Shifts 154 The Gaps in Current Regulatory Policy and Governance 156 A Strategic Regulatory Agenda and Related Institutional Reform 158 From the Lecture: Richard Thorpe’s SIRP Lecture Comments 163 From the Lecture: Elizabeth May’s SIRP Lecture Comments 171 From the Lecture: Janet Yale’s SIRP Lecture Comments 177 From the Lecture: Panel Discussion and Q & A 183 Q & A With Audience 193 xvi Preface by Anne Golden President and Chief Executive Officer The Conference Board of Canada F or many years, Canadian business leaders have been complaining that this country’s excessively numerous and complicated regulations are driving up costs and hurting their competitiveness. It is a problem only heightened by the inefficiencies of our fractured federal system—the theme of our inaugural Scholar-in-Residence volume, which appeared in 2006. At the same time, however, consumer and advocacy groups insist that Canada’s regulatory system is inadequate to protect individuals and the environment from potential harm caused by new products and processes being brought to market. For these reasons, The Conference Board of Canada chose to make the topic of regulation—under the rubric of “Red Tape, Red Flags”—the focus of the second year of our CIBC Scholar-in-Residence program. We were honoured to have renowned Canadian public policy expert Dr. G. Bruce Doern as our Scholar-in-Residence, and to have featured his year-long research project at the CIBC Scholar-in-Residence lecture at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa on May 23, 2007. The full fruits of his research are presented in this volume. We were equally delighted to have on stage that evening a stellar panel of commentators well acquainted with regulatory challenges: the Honourable Rick Thorpe, Elizabeth May and Janet Yale. Presiding over the event as host and moderator, for the second year in a row, was Allan Gregg, whose own public policy expertise is formidable. The event is represented in this volume in the form of the commentators’ remarks and highlights from the subsequent discussion among Gregg, the panellists and the audience. The Conference Board is deeply grateful to CIBC for its vision and generosity in providing 10-year funding for our Scholar-in-Residence series, which made possible the present volume and will fund future ones. With its mission of advancing thought leadership for a better Canada, the Conference Board is proud to present this important research study and associated commentaries. We hope it will help leaders—at all levels of government, as well as in the business and non-profit sectors—improve Canada’s regulatory system. Preface Foreword by Allan Gregg I started working on Parliament Hill, many years ago, for the Office of Opposition Research. Funded by the Library of Parliament, our job was to provide policy analysis and a counterbureaucratic resource for Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition. Every day, we would come to work brimming with excitement about the prospect of Question Period. The parry and thrust of that one hour of singlemember combat always got our blood rushing. Opposition day—with its remote possibility of making a difference to the government’s legislative agenda—was also always greeted with much anticipation. Even committee work, where the MPs you worked with could score points or hold ministers accountable, was exciting. The one thing, however, that was typically met with dread and groans was the moment when the departments we were monitoring issued their annual “regs.” These huge tomes were complicated, impenetrable and often ridiculously arcane. Worse, no one cared. The press gallery was bored gormless by the whole exercise, and there was no way you were going to get any media attention, even if you were able to unearth some onerous new regulation that had been slipped in somewhere. Yet we all knew that the “regs” could make a huge difference to the lives of individuals and the operations of institutions. They set out the broad rules of behaviour for society’s stakeholders operating in the public sphere and were backed up by the sanction of the state. In other words—regardless of whether anyone cared, or whether the lion’s share of regulation occurred under the radar and out of the glare of press or parliamentary scrutiny—they mattered. Regulations have the power to put companies out of business; to create or destroy fortunes; and to expose the public to, or protect it from, harm. As you will find in reading this landmark work, regulations are becoming more, not less, important in an age of exploding technology, innovation and globalization. First, as Professor G. Bruce Doern has discovered, creating, monitoring and implementing regulations represents a huge proportion of the government’s total output—about onethird of everything it does. Foreword Second, because most regulatory changes are amendments to existing regulations, they have a tendency to pile up. At the May 2007 public lecture on the topic of this publication, the Honourable Rick Thorpe, British Columbia’s Minister of Small Business and Revenue and Minister Responsible for Regulatory Reform, talked about his Herculean efforts to reduce his government’s total regulatory burden. They have been remarkably successful, having eliminated over 40 per cent of provincial regulations—and yet B.C. still has approximately 220,000 left on the books! Third, due to the increasing complexity of many of today’s issues and organizations, regulations do not fit nicely into either the geographic or the administrative boundaries over which regulators have jurisdiction. Imagine setting up an oil refinery in, say, Lloydminster today. Which province would have a say over its emissions standards: Alberta or Saskatchewan? Even discounting the geographic oddity of this example, royalty structures would fall under provincial jurisdiction, yet capital cost allowance calculations would be submitted to Ottawa. You would have to deal with Natural Resources Canada and Environment Canada, too. And if you were seeking an export licence, you would have to abide by regulations set out by Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. If you had transmission lines that bordered on a reserve or ran through an area that was part of a land claim dispute, you would be making a visit to Indian and Northern Affairs Canada as well. Canadian federalism, with its built-in character of “shared sovereignty,” adds inherent complexity to regulation. The apocryphal story of the truck driver who has to stack his lumber one way, only to have to unload and restack it another way as he crosses provincial borders, is almost laughable—to everyone but the truck driver who is doing the restacking. In 1994, all provincial governments joined with the federal government to sign the Agreement on Internal Trade, designed to reduce some of this regulatory complexity. Thirteen years later, scant progress has been made in meeting that goal, and the consensus is that little political will exists to tackle the monumental tasks of negotiating and Red Tape, Red Flags unravelling that would be required to harmonize regulation across provincial boundaries. As international trade agreements knit the world more closely together, the movement of goods, services and people across national borders generates another layer of regulatory asymmetry. While meeting in Montebello at their annual summit in the summer of 2007, the leaders of Canada, the United States and Mexico illustrated the problem by drawing our attention to the plight of jelly beans: it seems that Ganong, a Canadian maker of said jelly beans, has to comply with three different national sets of packaging requirements in order to take advantage of the North American Free Trade Agreement. The complexity of multi-agency, multijurisdictional and multinational regulation leads to the “red tape” that drives business to distraction. It can have a demonstrably deleterious effect on Canada’s national competitiveness, not to mention its attractiveness as a place to invest. But regulations do not produce only red tape. The fact that they exist can also be a signal that someone has set off “red flags”— warnings that, without regulation, public safety, health and the environment might be imperilled. It seems perfectly logical that a truck driver should be able to stack his wood the same way in Alberta and B.C., but what if nursing certificates take two years to earn in one province and four years in another? Do we eliminate interprovincial differences in regulation and facilitate interprovincial employment by lowering the bar to two years for all nurses, and in doing so set a similarly lower standard for the quality of our health care? (In this case, it is far less likely that certification requirements would be raised, because nurses with two-year degrees would then be functionally de-certified.) Again, few would argue with the logic of implementing identical crossborder packaging regulations for jelly beans, but would Canada really want to adopt U.S. standards for chemical warnings, or Mexico’s minimum wage policy? In the larger context, the dual function of regulation—as red tape and red flags—forces us to ask whether eliminating or harmonizing regulations offers us the key to unlocking our national competitiveness, or whether instead it represents a “race to the bottom” that invariably Foreword leads to lower standards and greater threats to our health, safety and the environment. From the latter perspective, regulation is seen not as a burden, but as the bridle that reins in private interest when its pursuit threatens the public good. Even in those instances where government intervention and regulation is more often welcomed than feared, however, today’s realities conspire to complicate straightforward regulatory decision making. Most of us would agree that patent protection and testing of prescription drugs are good things in that they safeguard intellectual property (thus offering companies an incentive to conduct future research) and shield the public from the harmful effects of any unsafe drugs. But what if a drug purported to cure cancer was patented in another country or jurisdiction? Would Canadians be so accepting of a “madein-Canada” approval process for this new drug that might take years to run its course? And what if the makers of this miracle cure then offered to sell their drug through the Internet? Or, better yet, what if a generic drug company produced a non-branded version and sold it through its own virtual pharmacy? What then happens to the entire regime of patent protection, drug testing and formulary registration in Canada? What is clear from Professor Doern’s research is that the Internet and digital transmission of content threaten to turn the regulation of entire sectors completely on its head. Throw into this mix cutting-edge disciplines such as biotechnology, reproductive technology and nanotechnology, and the question becomes whether governments have the internal scientific know-how to generate a regulatory regime capable of determining what is harmful and what is beneficial in these fields. Even a cursory glance at the regulatory landscape would suggest that there are no easy answers to these questions. What makes solutions even harder to come by, however, is the fact that the issue is rarely, if ever, the topic of discourse or debate anywhere, whether in Parliament, the press or the public square. The result is that regulatory changes are made incrementally, in isolated silos, and often in the absence of a full understanding of their consequences. As a result, governments risk generating both too much bad regulation and too little good 10 Red Tape, Red Flags regulation—with the public, industry and the nation the worse for keeping the issue under a bushel. Professor Doern’s pioneering study shines light into these murky corners where regulation has been largely hidden from scholarly analysis or public debate. He first looks outside of government to the larger societal forces that are both driving and challenging the regulatory agenda. Here he finds that the speed of change itself—be it scientific or economic—has generated concurrent pressures to both reduce existing regulations and generate new ones. Business cites the “red tape” of regulation as a principal barrier to competitiveness, and consumers demand faster access to new products and innovations. At the same time, however, rapid advances in science and commerce induce a fear of the unknown that produces calls for greater protection, reduced uncertainty and “science-based risk regulation.” Against this larger background, Professor Doern examines how government actually operates and how regulations evolve. Notwithstanding efforts such as “smart regulation” and more rational attempts to prioritize regulatory reform, he discovers that the prevailing tendency is a “one regulation at a time” approach, with little cross-jurisdictional coordination of activity. Indeed, he concludes that this ad hoc, “siloed” approach, and the absence of any systematic evaluation and reexamination of regulations, have produced simultaneous cries for less red tape and more red flags. Governments are required to deliberate their priorities in the Speech from the Throne and their plans for spending in the Estimates; Professor Doern points to the wisdom of intro­ ducing a similar regulatory agenda-setting process. As a young policy analyst, I, like so many others, believed that government regulations were both boring and unimportant. I think that, in this book, G. Bruce Doern will convince you otherwise on both fronts— as he has me. Foreword 11 Introduction M aking regulations and rules, and enforcing and ensuring compliance with them, is at least one-third of what governments do—either alone or, increasingly, in concert with other key stakeholders in a modern 21st-century national and global political economy. Governments also tax, spend and persuade. This analysis of regulation in the innovation age will make some broad comparisons between regulation and these other core modes of policy making and governance, particularly taxation and spending, in order to discuss a fundamental strategic gap in Canada’s regulatory architecture and democracy. This gap is three-fold. The first gap is an institutional weakness in dealing with the complex regulatory regimes of multiple regulators, as opposed to dealing with one regulation or one regulator at a time. The second and closely linked gap is the absence of a visible regulatory agenda or set of openly debated annual regulatory priorities. The third gap is the misconception that the red-tape and red-flag values inherent in regulation are as oppositional as they were in the past. In many practical regulatory situations where innovation is involved, these values are often integrative; both business and social stakeholders have a strongly linked interest in both reducing red tape and protecting health, safety and environment as new products emerge. Of course, there are still some tensions between these two concerns, but these values are much more entwined than they were two decades ago. The overall purpose of this study is to examine and draw more considered attention to Canada’s complex regulatory regimes, as well as the management challenges these regimes present. Such regulatory regimes consist of multiple regulatory agencies, laws, rules and processes—not only within the federal government, but also across international, provincial and local levels of government. To deal with the three gaps mentioned above, Canada needs a much more strategic approach to regulation, regarding both the development of new rules and the enforcement of existing ones. Changes are needed to deal fully and effectively with Canada’s regulatory challenges in the innovation age, including the democratic deficits inherent in current approaches. Introduction 15 The Three Central Arguments In this study, I advance three closely linked central arguments tied to the three gaps. This study expands these arguments through three chapter-length case studies of regulatory regimes and through an examination of federal regulatory policy. The central arguments are as follows: The red-tape and red-flag regulatory issues that concern Canadians are no longer as diametrically opposed as they once were. Rather, to a much greater extent in the innovation age than before, they reinforce each other. In many specific situations, both business and social stakeholders have a mutual interest in enhancing efficiency and in managing risks effectively. Despite lingering tensions between these two concerns, political interests can be configured on both sides of the red tape/red flag equation, in different circumstances and situations. Current federal regulatory policy is based far too much on a oneregulation-at-a-time approach, combined with once-a-decade regulatory reform exercises. More effective ways of managing complex regulatory regimes are needed. Regime-level issues need more focused examination, both when new regulations are proposed and when product and project approvals—and compliance and enforcement issues—are addressed under existing regulations. The federal government needs to develop a transparent annual regulatory agenda so that priorities and resource needs can be announced, debated and agreed on. Such agendas are already broadly used for governmental taxation and spending decisions and plans. For some time, governments have had overall policies on regulation and have thought about aspects of setting a regulatory agenda. However, they have not come even close to establishing a transparent annual regulatory agenda that would complement their spending and tax agendas. The architecture of federal regulatory governance also needs more transparent arm’s-length advice, provided through a suggested Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. 16 Red Tape, Red Flags Examples of the new complexities of multi-agency and multi-level regulation are not hard to find, nor are the reasons for finding a more strategic approach to dealing with them. Drug regulation, for example, increasingly involves dealing with significantly rising volumes of new drug applications. The cycle of premarket review and approval, post-market assessment and monitoring, and payment for such drugs under medicare, involves multiple regulators and participants, including Health Canada; networks of patients, consumers and health professionals; and provincial health departments. Shared knowledge and input from U.S. and international regulatory agencies are also critical. Drug regulation is partly sectoral, but pharmaceutical companies are simultaneously affected by hori­zontal regulations from intellectual property bodies and regulations from health authorities with broad public health concerns. Canada’s dismal performance in reducing greenhouse gases, in relation to the current climate change debate, is by no means the only example of a non-strategic approach to energy and environmental regulation. Years ago, governments recognized the problems of coordinating the regulatory review of new energy projects with the need for environmental assessments at different levels. At the federal level, this process involves both Environment Canada’s Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency and Natural Resources Canada’s National Energy Board, to name only two entities. The environmental assessment agency has a horizontal mandate, in that its assessments cover new developments and projects across a range of firms and sectors, only one of which is the oil and gas sector. While coordination between federal agencies has been enhanced somewhat, progress has been slow. Taking a decade or more to change is no longer good enough in a fast-changing global economy. That is true both in terms of meeting energy needs and meeting the always-connected need for environmental protection. Introduction 17 Key Definitions and Conceptual Issues This study of red-tape and red-flag regulation looks closely at regulation in the innovation age with the above institutional gaps in mind. The key concepts in the title of this book are in one sense easy to define, but in practice not easy for regulators and citizens alike to penetrate and deal with. Red tape is, of course, one of the oldest negative labels for governing in general and regulating in particular. It implies excessive rule making, unnecessary procedural complexity, or inflexible behaviour and decision making by regulatory authorities, or simply by “bureaucrats.” Red flags, as a label, has had less continuous historical use than red tape, but it is nonetheless a useful shorthand term to depict concerns about real or perceived danger or risk linked to health, safety or the environment. Such risks range from the safety of nuclear reactors, aircraft and automobiles to fraudulent sales practices in any number of product and service markets. The concept of red flags also increasingly implies not just risks to current citizens, communities and firms, but also to future ones and hence to intergenerational health and safety and to longer term sustainable development. The term innovation age is intended to capture the current socioeconomic era, in which entire systems or regimes of rule making and compliance must be examined in relation to the knowledge-based economy and to continuous rapid changes in product development, industrial processes and institutional experimentation. These dynamics are propelled by massive changes in telecommunication and information technology, by globalization at both economic and social levels, by intricate and changing supply chains, and by increasingly varied but also conflicting notions of the kinds of democracy that ought to be practised in the innovation age. Regulation in the innovation age also strongly implies regulation that is science and technology based, even when the science is contested. 18 See The Conference Board of Canada, Including Innovation in Regulatory Frameworks (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2004). Red Tape, Red Flags Throughout this study, I define regulation quite broadly as rules of behaviour backed up by the sanctions of the state. However, such rules are variously expressed through laws, delegated legislation (or the “regs”), guidelines, codes and standards. Thus, there are many levels and types of rule making even in the core definition of regulation. This issue of everyday importance in regulatory realms will also arise when one is thinking about what ought to be included in and excluded from an annual national regulatory agenda. Guidelines and codes, for example, are often seen as realms of “soft law” or rule making in the shadow of the law. Regulatory regimes refers to areas of rule making and compliance where two or more Canadian or international regulatory bodies jointly and continuously affect, for good or for ill, the product cycles, production processes and investment choices of firms and the choices of individual Canadians as consumers and citizens. Regimes include not only the agencies involved but also the laws and rules themselves, the rule-making process, and the product or project approval process. Such regimes also have ever-more complicated accountability issues to face and manage. It is not difficult to find examples of such regimes. Three are examined in this study, but other analyses also highlight the existence of these complex regulatory governance systems. For example, a recent Conference Board of Canada study looked carefully at health profession self-regulation and discussed whether these professions could be encouraged to use collaborative processes to break down some of the barriers among professions in health-care diagnosis and delivery. The authors mapped and analyzed a dozen or more medical and health For definitional discussion, see G. Bruce Doern, Margaret Hill, Michael Prince and Richard Schultz, eds., Changing the Rules: Canada’s Changing Regulatory Regimes and Institutions (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), and P. Eliadis, Margaret Hill and Michael Howlett, eds., Designing Government: From Instruments to Governance (Montreal and Kingston: McGillQueen’s University Press, 2005). For discussion, see Doern, Hill, Prince and Shultz, Changing the Rules, Chapter 1. See Peter J. May, “Regulatory Regimes and Accountability,” Regulation and Governance 1, 1 (March 2007), pp. 8–26. Introduction 19 professions in each province, along with the laws and rules regarding self-governance and ethics for these professional realms. This book also deals with regulatory governance and the various institutional forms it takes. Such governance increasingly involves a series of joint actions between the public and private sectors, including various kinds of self-regulation and co-regulation. A focus on regulatory governance recognizes that regulation has to be conceived as rulemaking processes, outputs, and compliance and enforcement actions and outcomes that can emerge from varied top-down, bottom-up and negotiated processes within the government, among governments, among provinces and cities, and among economic and social interests and stakeholder groups. This study is therefore premised on a recognition that regulation and regulatory regimes are increasingly characterized by multi-level regulation and governance. This has, in one sense, always been an issue in any kind of political system. It has certainly always been a central feature of Canadian federalism, where challenges regarding both regulatory competition and cooperation among national and provincial governments are well documented. Whereas it was once common to think of regulatory levels mainly in terms of federal and provincial jurisdictions, it is now essential to include international levels of regulation and dispute settlement in trade, corporate governance and competition law, and in various sectoral realms such as drugs, energy, and telecommunication and Internet regulation. Significant and serious issues emerge regarding international regulatory cooperation and harmonization but also regarding the inherent challenge of a global disaggregation of authority—regulatory and otherwise. See The Conference Board of Canada, Achieving Public Protection Through Collaborative SelfRegulation: Reflections for a New Paradigm (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2007). J. Jordana and David Levi-Faur, The Politics of Regulation: Institutions and Regulatory Reforms for the Age of Governance (Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 2004). G. Bruce Doern and Robert Johnson, eds., Rules, Rules, Rules, Rules: Multilevel Regulatory Governance (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006), Chapter 1. 20 See James N. Rosenau, “Governing the Ungovernable: The Challenge of a Global Disaggregation of Authority,” Regulation and Governance 1, 1 (Blackwell Publishing, March 2007), pp. 88–97. Red Tape, Red Flags The federal government does not routinely make public the number of new regulations proposed or passed each year. A 2002 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) study of Canadian federal regulation showed that the rate of growth in federal regulation had declined in the preceding decade. This finding on growth refers only to delegated legislation and does not include laws or other forms of rule making, as discussed later in this introduction. The overall number of annual new regulations (delegated law) would appear to be in the range of 400 to 500; however, of these, about 90 per cent are amendments. That suggests that 40 to 50 new regulations are proposed each year and wind their way through the various regulatory stages. (See Chapter 1 for further discussion.) Occasionally, there are bursts of new regulation, such as the one that occurred in the wake of post-9/11 security concerns. It must be stressed, of course, that none of the above deals with the existing stock of regulations, which remains large and which has been subject in Canada and elsewhere to various efforts either to get rid of old rules or to reduce the paper burden of accumulated rules. None of the above includes the growth of provincial, regional or municipal regulation. Structure and Preview of the Framework To explore the logic of, and evidence supporting, these linked arguments and issues, the study proceeds in three main stages. Chapter 1 attributes the current dilemmas inherent in the first argument to three interacting forces: The speed and complexity of underlying economic and technological change, which leads to concerns about (a) competitiveness, when the costs and burdens of regulation are too onerous Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Canada: Maintaining Leadership Through Innovation, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform (Paris: OECD, 2002). Introduction 21 (red tape); and (b) the protection of the environment, health and safety for current and future generations (red flags). Expanding consumer demands for faster access to new products (red tape) and continuing citizen concerns about democratic engagement and openness in regulatory processes and decision making (red flags), which may make regulatory decision processes longer. The increasingly intricate, science-based nature of risk regulation and the need for government science and technology (S&T) capacity in the innovation age. Regulation is more complicated in the innovation age because of the speed of scientific and technological change. Thus, a related key reason why more strategic approaches to regulation are required is that the federal government has not invested in its internal S&T capacities, even while signing up for more and more regulatory obligations, nationally and internationally. Far too often, the science-based regulatory system is playing a catch-up game rather than a get-ahead-of-the-curve game. These three forces are contrasted in Chapter 1 with the starkly opposite nature of current federal regulatory policy, which, despite some recent improvement, is still largely dominated by the one-regulationat-a-time approach and by periodic regulatory reform exercises every decade or so. In chapters 2, 3 and 4, I examine three case studies of complex regulatory regimes in the following realms: pharmaceutical drugs and overall public health (Chapter 2); biotechnology and intellectual property (Chapter 3); and energy and the environment (Chapter 4). The first two regimes are quite closely linked, especially since they analyze and approve related but different health products. Table 1 previews the overall framework used in the three regime case studies. In each of these case study chapters, I employ a common analytical approach and set of analytical headings. First, I map the core features of the regulatory regime. Each chapter begins with a text box listing the agencies involved and a second text box listing some of the core processes involved in assessing and approving products—or, in the case of the energy–environment regime in Chapter 3, projects. Then I set the 22 Red Tape, Red Flags Table 1 Preview of Framework for Regulatory Regime Case Studies Framework Element Core regime agencies, actors and processes (regulation making, and product and project approvals and compliance processes) (Examples only: see chapters 2, 3 and 4) The Pharmaceutical Drugs– Public Health Regime The Biotechnology–Intellectual Property Regime The Energy–Environment Regime Health Products and Food Branch of Health Canada Canadian Intellectual Property Office National Energy Board Commissioner of Patents Provincial and territorial energy boards Biologics and Genetic Therapies Directorate of Health Canada Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission Therapeutic Products Directorate of Health Canada Networks of health professionals and patients Drug companies Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Canadian Expert Drug Advisory Committee Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee Canadian Biotechnology Secretariat Nuclear Waste Management Organization Natural Resources Canada Environment Canada World Trade Organization and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Provincial environmental assessment agencies Provincial drug formulary approval authorities Canada’s Access to Medicines Regime U.S. Food and Drug Agency Genetics clinics, family physicians and patient groups Canadian Institutes of Health Research granting rules and guidelines 23 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission North American Electricity Reliability Organization Commission on Environmental Cooperation (North American Free Trade Agreement) (cont’d on next page) 24 Table 1 (cont’d) Preview of Framework for Regulatory Regime Case Studies Framework Element The Pharmaceutical Drugs– Public Health Regime The Biotechnology–Intellectual Property Regime The Energy–Environment Regime Context, regime change and evolving criticism The thalidomide model and the premarket safety focus Intellectual property and biotech in innovation agendas The backlog problem and slow approval times Industry pressures and fastchanging industry dynamics Energy industries, project approvals and incentive-based regulatory flexibility New and high volume drugs and re-balancing pre-and post-market regulatory review Intellectual property rights, public health and global access to patented life-saving products Health Canada’s Blueprint for Renewal in an Innovation Context Internalization of environmental costs in energy prices Sustainable development as a policy–regulatory paradigm The climate change debate and policy–regulatory failure Alternative renewable energy sources and projects and regulatory push Illustrative regime change Access to drugs and the Common Drug Policy phase of the regime Access to genetic diagnostic test products Environmental assessment and energy projects Conclusions re: a) red tape and red flags b) the three core forces in the innovation age c) the agenda-setting gap and other institutional reform implications See chapters 2 and 6 See chapters 3 and 6 See chapters 4 and 6 context for the regime, recent key changes in it and evolving criticisms of it. These are clearly different for each regime for the obvious reason that the substance of regulation in each regime is different. Each chapter then focuses on a more recent illustrative example of regime debate and pressure for change. For example, chapters 2, 3 and 4 respectively examine access to drug products under the Common Drug Policy, access to genetic diagnostic tests, and the environmental assessment of energy projects. Conclusions are offered in each chapter regarding the regime’s red-tape and red-flag dimensions and changes; innovation issues linked to the three forces outlined above, as they relate to regulation-making and regulatory compliance and enforcement issues; and the reasons why the gap in annual agenda setting and related institutional reform matters. It must be stressed from the outset that the three regulatory regime case study realms are multi-faceted and that limits of space mean that key issues and dynamics can only be highlighted rather than fully mapped. The substantive nature of regulation in each regime and the reasons for its intricacy must be appreciated within these brief portraits. I am also obviously interested in key issues that emerge cumulatively across the three chapters regarding mixtures of both new regulatory proposals, but also the crucial dynamics of product versus project approvals, and regulatory compliance and enforcement. In the third and final stage in Chapter 5, the book zeroes in on what is wrong with the current federal approach to regulation. It then examines the overall need to better manage regulatory regimes by making the case for a national regulatory agenda and for related institutional reform through the suggested creation of a Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. It does so by first looking at whether a regulatory agendasetting process exists now, and then discussing what a more complete process might look like and how it might function to Canada’s political, economic and democratic advantage. I make the case for a regulatory agenda partly by revealing and examining the middle-level issues and evidence in the three case studies, but also by using a macro and broader logic linked to the overall red-tape and red-flag themes and to the meaning of regulatory Introduction 25 democratic debate and governance in the innovation age. The case for an annual regulatory agenda is not advanced as a panacea for all the problems of politically and economically managing complex regulatory regimes. An agenda is seen as part of the missing architecture of Canada’s regulatory governance system, along with the abovementioned Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. The methodology employed in the analysis is fairly straightforward. The larger aspects of the analysis draw on published literature and on governmental and private sector studies. The same is true for the three case studies, but research on these three regimes and on the current regulatory system overall has been complemented by some interviews with key players. It also draws on my past and recent research into these complicated realms of rule making and compliance. The question of how representative the three chosen case studies are has also been central to my analytical considerations. Clearly, I could have selected many other regulatory regimes, including transportation (air, rail and water), competition law, trade, financial services, securities, corporate governance, or borders and security, to name only a few. These regimes also possess the core characteristics of complexity found in the case studies, as well as the mixtures of product approvals, project approvals and spatial realities. Thus, I have a high degree of confidence that the three case study regimes are reasonably representative of the complex regulatory regime issues and challenges examined in this study. 26 Red Tape, Red Flags 1 Key Forces for Regulatory Change and the Current Regulatory Policy Context T he general argument about complex regulatory regimes and about regulatory agenda setting being advanced in this study needs to be made within a clear overall view of the key forces for regulatory change in the innovation age and of the current regulatory policy and governance context. This chapter first explores the three key forces referred to in the Introduction: the speed and complexity of underlying economic and technological change; consumer demands for increased access to new products, and citizen demands for democratic engagement in regulation making; and the intricate, science-based nature of risk regulation. I then examine the current regulatory policy that governs regulatory decision making, a policy centred mainly on a one-regulation-at-a-time approach, complemented by regulatory reform initiatives conducted every decade or so. The red-tape and red-flag challenges and choices of regulation and regulatory governance are buffeted by the three interacting forces, albeit in varied and sometimes contradictory ways. My discussion of the current regulatory policy context outlines what current regulatory policy is, how it has evolved in relation to past regulatory reform initiatives, and why it is inadequate for regulation in the innovation age, where fast-changing and complex regulatory regimes must be managed. The Three Key Forces for Change The Increased Speed and Complexity of Underlying Economic and Technological Change The first force driving change is the increased speed and complexity of underlying economic and technological development. This force leads to concerns about (a) competitiveness, when the costs and burdens of regulation are too onerous (red tape); and (b) the protection of the environment, health and safety for current and future generations (red flags). It is taken as an analytical and practical given that regulation in Chapter 1 29 the innovation age is propelled by rapid, wide-ranging change in fields such as information technology, biotechnology and nanotechnology. Examples here are not difficult to find, as any number of biotechnology food products and bio-health, genome-centred products line up for regulatory review and approval in Canada and globally. Increasing numbers of these products and production processes involve the convergence of biotechnology, information technology and nanotechnology. These fields do not obey the normal boundaries of departmental regulatory jurisdictions or levels of government. New, enhanced capacities to deal with regulation in these areas are needed. Governments can no longer rely on regulatory reform every decade or so. There must be a greater capacity to assess regulatory change on an annual strategic basis with more systematic, overall data on and analysis of regulatory demands, risk profiles and risk-benefit issues. Much of this change is linked to globalization, but globalization itself is a mixture of linked driving forces. These forces include increasingly global production location and sourcing decisions, and related supply-chain considerations; massive increases in the mobility and movement of capital; significant increases in the mobility of labour, especially highly qualified personnel; and the development of the Internet, and related telecommunication products and processes. The business community has for some time expressed strong concerns about the adverse effect of regulatory costs and cumulative regulatory burdens on the investment climate. These arguments have been made repeatedly and have linked regulatory costs and burdens to Canada’s declining productivity vis-à-vis the U.S. The business community has argued that Canada needs to look closely at entire regulatory systems to Peter Philips, Governing Transformative Technological Innovation: Who’s in Charge? (Oxford: Edward Elgar, 2007), and Bill Woodley, The Impact of Transformative Technologies on Governance (Ottawa: Institute on Governance, 2001). Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, Biotechnology and the Health of Canadians (Ottawa: Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, 2004). 30 Red Tape, Red Flags determine whether they act as barriers or incentives to innovation and investment in Canada. Rapid, complex change increasingly requires that governments have a capacity to continuously examine entire systems of rule making, enforcement and compliance. In its 2004 report, the federal External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation partly recognized this need. However, the committee did not tie it to another necessary institutional capacity: namely, an explicit strategic regulatory agenda that is publicly debated. This agenda would address regulatory priorities in an integrated way to limit the complexity of regulation and to ensure that new regulations respond to economic and technological changes. Consumer Demands for Faster Access to New Products The second force influencing regulation centres on growing consumer demands for faster access to new products (reduced red tape), linked to citizen concerns about democratic engagement and openness in regulatory processes and decision making (red flags) that may make regulatory decision processes longer. Regarding product approvals in areas such as foods, drugs and health products, consumers are likely to demand fast, safe access to these products, especially when they know they are already available and have been given regulatory approval in other countries. E-commerce and the Internet in general are the main reasons Canadians are becoming aware much faster of product availability in other countries. Other countries’ consumers are equally aware of Canadian products and may want access to them quickly. American demand for online sales of lower-priced drugs from Canadian pharmacies is an excellent example of the latter trend. The Conference Board of Canada, Including Innovation in Regulatory Frameworks, 4th Annual Innovation Report (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2002). See also Bryne Purchase, Regulation, Growth and Prosperity (Ottawa: Policy Research Initiative, 2006), and Roy Atkinson, Developing a Framework for Assessing Innovation, Productivity, and Business Impacts of Regulation (Ottawa: Policy Research Initiative, 2006). External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, Smart Regulation: A Regulatory Strategy for Canada (Ottawa: External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, 2004). Chapter 1 31 The issue of fast access to drugs and related health products takes on a special additional meaning when certain patients or disease groups want new drugs immediately to help in life-saving situations. Drugs targeted at small subpopulations are increasingly expensive for firms to develop and for provinces to fund under public health care. As chapters 2 and 3 will show, more and more of these drugs are coming onto the market with enormous impacts on Canada’s health-care system and health-care costs. Demand for fast access to new and cheaper drugs to help deal with the AIDS epidemic in Africa and elsewhere is also an international example of great importance, one in which Canada’s response still faces serious contradictions between red tape and red flags. While it is clear that Canadians as consumers want faster access to products, it is also clear that Canadians as citizens still strongly support democratic engagement in decision-making processes related to new regulations and product approvals. A 2004 study of public opinion polls regarding regulation showed that Canadians tend to associate public interest regulation with regulation related to health, safety and the environment. They also tend to think that such regulatory processes should include opportunities for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and individual citizens to participate in transparent ways. However, the study revealed that Canadians also believe that businesses in general are subject to too much regulation and that these regulations are too complex. The study also showed that Canadians as a whole are not opposed to regulatory cooperation at the international level, but they are more critical than business interests typically are about too close a link to the U.S. They feel this way even though, on average, Canadians trust the capacity of U.S. regulators to be good regulators. Indeed, every day, Canadians buy U.S. products approved by such regulators. See Matthew Mendelsohn, “A Public Opinion Perspective on Regulation,” paper prepared for the External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation (2004). Ibid. 32 Red Tape, Red Flags A strategic regulatory agenda would help better identify these fastoccurring tensions regarding access and democratic engagement. It would also help identify the institutional arenas and capacities needed to manage these challenges and tensions effectively. The Complex, Science-Based Nature of Risk–Benefit Regulation The third force to emphasize is the increasingly complex, sciencebased nature of risk regulation and the need for government science and technology (S&T) capacity in the innovation age. Regulation is more difficult in the innovation age because of the speed of scientific and technological change and the nature of the science needed to deal with interacting hazards, pollutants and emissions. A related key reason why more strategic approaches to regulation are required is that the federal government has not invested sufficiently or regularly in its internal S&T capacities, even while signing up for more and more regulatory obligations, nationally and internationally. Far too often, the science-based regulatory system is playing a catch-up game rather than a get-ahead-of-the-curve game. This situation must be remedied. It will take a willingness and capacity to think and act strategically regarding science in government, particularly the science needed to support regulation. The complex, science-based nature of risk regulation—or, more accurately, “risk– benefit” regulation—significantly influences regulatory governance in many fields and in overlapping regulatory regimes. Science-based regulation refers to regulatory (and related policy) decision making in which scientific knowledge and personnel play significant roles. However, for several reasons, this definition is only a starting point. First, science as an activity within government involves both research and development (R&D) and related science activities (RSA). Hence, it involves diverse tasks, such as research, monitoring Christopher Hood, H. Rothstein and Robert Baldwin, The Government of Risk: Understanding Risk Regulation Regimes (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2001). See G. Bruce Doern and Jeffrey Kinder, Strategic Science in the Public Interest: Canada’s Government Laboratories and Science-Based Agencies (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007). Chapter 1 33 and assessment; technology and indicators development; and reporting activities. As undertaken in government, science is thus not homo­ geneous but, rather, involves an interrelated set of activities. The Relationship Between Regulation and Innovation Cumulatively, the above three forces have led to analytical efforts to better understand the key links and overall interactions between regulation and innovation in contexts where (a) excessive or improperly designed regulation may prevent or lessen innovation; and (b) strong, effective regulation may create opportunities for innovation to flourish. All regulation shapes markets in some fashion. These “shape-shifting” impacts may, in turn, help produce both intended and unintended innovations and ways of doing things in multi-faceted markets. The basic argument to emerge from this discussion is that regulation, depending on its nature, can either harm—or, indeed, prevent—product, process and institutional innovation, or encourage it. Much depends on the exact design of regulatory programs and on the complementary use of other policy instruments. All of these should be aligned in such a way that desired impacts—such as reducing pollution or improving health— are achieved, but in ways that also foster efficiency and political legiti­ macy and support. Technologies produced through innovation are crucial to the capacity of the regulator to regulate and to monitor impacts. For multiple regulators, these changes have two concurrent effects. They simultaneously affect regulation in both the sectoral/vertical and framework/horizontal realms of rule making. In short, they affect complex “regime” regulation, as examined in this study.10 Secondly, they affect both overall rule making and compliance, and the product and See Mark Jaccard, Mobilizing Producers Toward Sustainability: The Prospects for SectorSpecific, Market-Oriented Regulations, in Glen Toner, ed., Sustainable Production: Building Canadian Capacity (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006), pp. 131–153. 10 See G. Bruce Doern and Ted Reed, eds., Risky Business: Canada’s Changing Science-Based Policy and Regulatory Regime (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000). 34 Red Tape, Red Flags project approval aspects of regulation that function within the ambit of those larger rules. Product approvals in some sectors, such as drug and food regulation, are the core high-volume business of regulators. Other regulators, such as those in the energy–environment field, may be dealing with a combination of new products and new projects, with the latter often involving multiple environmental assessments by several regulators. The analysis of the interactions between regulation and innovation starts with a necessary discussion of the non-linear nature of innovation dynamics and of the need to be very cautious about simple “cause and effect” or “stimulus and response” bases for assessing effects and interactions. The analysis also shows that many studies have dealt initially or mainly with the impacts of regulation on investment or competitiveness, which may be only partly or indirectly linked to innovation per se.11 Innovation as a process that produces and commercializes new products and processes is central to this discussion, but so also is institutional or organizational innovation. These issues suggest as well the need to differentiate effects that might arise for firms from narrower compliance impacts of a particular environmental regulation and those that might affect the core business of that firm. All governments are actively developing policies and debating issues regarding how they can foster innovation in a world increasingly facing the global competitive challenges of a knowledge-based economy and also a knowledge-based society. Innovation policies and strategies are targeted at the development of new products and of new production and institutional processes. They place a greater emphasis on benchmark indicators such as rates of patenting and the creation of spin-off companies than on traditional measures such as rates of R&D as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Earlier linear models—which saw basic science leading to applied science and then to product development—are increasingly seen as overly simplified views of what happens in the dynamic economic and technical settings of the new economy. Most current innovation policies 11David Vogel and Robert A. Kagan, eds., The Dynamics of Regulatory Change (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, International and Area Studies, 2004). Chapter 1 35 see the underlying dynamics as non-linear. As a result, a changed policy debate is focusing on ideas such as national systems of innovation, and local systems of innovation and clusters. Both systems are seen as multidirectional interactions among firms, universities and governments, and their variously networked S&T personnel.12 One of the influencing factors that governments and industries are examining in this innovation setting is regulation and regulatory governance. However, since both parties already concede that innovation is non-linear, interactive and multi-dimensional, the study of regulation and innovation must also consider interactive dynamics rather than simple “cause and effect” impacts. One can see this fact at several levels of analysis. With regard to firms and markets, regulation and innovation must traverse several intermediary relationships and processes. Rule making and compliance affect not only levels of profit, but also the decisions of firms to invest in new capital equipment, in human capital, in locations for new plants, in any R&D they do, and in their capacity to finance, patent, manufacture and market new products or to adopt new production processes. Later observed successes or failures can thus be attributed to one or more of these intervening processes and decisions, including decisions by one or more states to regulate at all, to regulate in particular ways, to avoid regulation or to deregulate. Regulatory Policies and Reform: The Limits of the One Regulation at a Time and Periodic Regulatory Reform Approaches The second element that is needed to set the scene for my analysis is a basic sense of what regulatory policy is and how the federal regulatory system currently works under that policy. I will note briefly five key features of the current policy and the process it generates: the federal 12 The Conference Board of Canada, Exploring Canada’s Innovation Character: Benchmarking Against the Global Best (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2004). 36 Red Tape, Red Flags regulatory policy; the key regulatory decision stages; Department of Justice legal review processes; Cabinet review processes; and recent changes to the federal regulatory policy and new institutions. The current system has also been influenced by periodic regulatory reform exercises conducted every decade or so, which are examined later in this section. Current Federal Regulatory Policy and Decision Processes The first feature is the federal regulatory policy. Successive editions of the federal regulatory policy have evolved from initial 1986 requirements requiring consultation with affected parties and the public, as well as requirements for regulators to prepare a regulatory impact analysis statement (RIAS) and to pre-publish the regulatory proposal. Later additions to the policy included the following decision criteria: ensuring net benefits to Canadian society (1992), minimizing regulatory burden (1995), fostering intergovernmental coordination and cooperation (1995), reflecting the Regulatory Process Management Standards (1995), and linking to Cabinet directives (1999). As Robert Johnson notes, the current edition thus now requires the following: consultation and participation of Canadians in the regulationmaking process; identification of a problem or risk, and justification that regulation is the best alternative; proof that benefits outweigh costs and that regulation is cost effective; minimization of regulatory burdens on the economy, which includes: − minimizing information and administrative requirements at minimal cost, − paying special attention to small business, and − giving positive consideration to parties proposing equivalent alternatives to regulation; adherence to international and intergovernmental agreements, and coordination across government and between governments; effective management of regulatory resources with: − Regulatory Process Management Standards, − a compliance and enforcement strategy, Chapter 1 37 − approval of adequate resources for enforcement responsibilities; and adherence to Cabinet directives.13 This evolving set of policy add-ons does indicate that some concern for coordination across governments and among levels of government has arisen, but such recognition has been more exhortative than compulsory in nature. The policy on regulation must also be linked to the overall steps for approving regulations, which are governed by the Statutory Instruments Act. There are three broad classes of regulations: Governor-in-Council (GIC) regulations, which include most regulations; ministerial regulations; and GIC or ministerial regulations affecting public spending. The 10-step process for approving regulations officially includes the following: planning of the regulation; drafting of the regulation; review by the Department of Justice; signature by the sponsoring minister; first review by the Privy Council Office (PCO); Treasury Board pre-publication in the Canada Gazette, Part I; updating of the proposal; second review by PCO; Treasury Board publication in the Canada Gazette, Part II (final approval); and Standing Joint Committee for the Scrutiny of Regulations. It must be stressed that these steps take place for each new regulation, one at a time.14 13 Robert Johnson, “Regulatory Policy: The Potential for Common Federal-Provincial-Territorial Policies on Regulation,” in Doern and Johnson, Rules, Rules, Rules, Rules, pp. 52–79. 14Government of Canada, Regulation Policies, Processes, Tools and Guides [online]. (Ottawa: Government of Canada). www.regulation.gc.ca. 38 Red Tape, Red Flags Department of Justice review also plays a key role in regulation. When a regulation is defined as delegated law flowing from a parent statute, then statutory drafting must be done under the watchful eye of Department of Justice lawyers to ensure the regulation falls within the powers and terms of the parent statute. Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms also comes into play, as Justice lawyers must ensure that proposed and final regulations do not infringe on the Charter. Cabinet-level review also warrants a mention here. Previously, a special committee of Cabinet reviewed regulations as statutory instruments, along with numerous Orders-in-Council flowing from laws and regulations or from the Governor-in-Council’s prerogatives. But the high volume of these items meant that this committee was not a priority-setting committee but, rather, a transactions-based, rapid-fire review committee. There is no such committee on the current federal government’s list of Cabinet committees. Other Cabinet committees, such as the Treasury Board, are involved in the process, as noted in the 10 stages outlined above. Other policy committees, the full Cabinet, and the Cabinet Committee on Planning and Priorities can certainly consider regulatory matters as new or amended regulations—as well as statutes packed with rules—proceed through the approval process. However, these deliberations are also mainly transactional, in a different sense. The internal processes also include some normal vetting of proposals by PCO and by the Regulatory Affairs and Orders in Council Secretariat of the Treasury Board. Such vetting can include checking on interdepartmental coordination issues, but at a highly transactional level as each item proceeds. None of these Cabinet-level or central agency-level processes is designed to review new regulations as part of an overall regulatory agenda. In the aftermath of the smart regulation process (discussed later in this chapter), further recent changes have occurred. In 2006 a Community of Federal Regulators was formed, supported by a very Chapter 1 39 small secretariat.15 It was created largely to ensure that federal regulators actually met to discuss common problems of structure, approach and capacity. However, it is certainly not intended to play a regulatory agenda role. In 2007, the federal Conservative government announced a new Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation.16 A new idea in the directive is that existing regulatory policy will be governed by a broader “life cycle” notion of regulation. This approach will take the existing policy on regulation beyond its current focus on the initial making of a regulation to the full later cycle of enforcement, compliance and eventual evaluation.17 The government’s first two commitments to Canadians in the new directive are that when regulating, the federal government will: “protect and advance the public interest in health, safety and security, the quality of the environment, and social and economic well-being of Canadians as expressed by Parliament in legislation; [and]” “promote a fair and competitive market economy that encourages entrepreneurship, investment, and innovation.”18 The directive also requires departments and agencies to prepare annual regulatory plans. I will return to these basic policy and decision structures and processes in Chapter 5, once I have examined the three regime-level case studies. However, what is crucial about overall federal policy is that as a set of rules about rule making, it is essentially still centred on a one-regulation-at-a-time approach now covering the full cycle of development, analysis, implementation and compliance. There is some recognition of the need for interdepartmental coordination, but that, too, is couched in the one-regulation-at-a-time logic. 15Government of Canada, Community of Federal Regulators: Business Plan 2005–2007 (Ottawa: Community of Federal Regulators, 2005). 16Government of Canada, Cabinet Directive on Streamlining Regulation (Ottawa: Treasury Board of Canada, Secretariat, 2007). 17 Ibid., pp. 9–10. 18 Ibid., p. 1. 40 Red Tape, Red Flags Periodic Regulatory Reform Initiatives The second way in which governments have tackled regulation is through periodic regulatory reform initiatives, once a decade or so. This section looks at this reform ethos and approach, beginning with the most recent federal smart regulation exercise and then quickly working backwards to earlier measures, debates and exercises, most of which still resonate today. The Smart Regulation Agenda The former federal Liberal government’s smart regulation agenda was announced in the September 30, 2002, Speech from the Throne (SFT). A multi-stakeholder External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation (EACSR) then guided and advised work on the initiative. The Chrétien government explicitly linked the rationale for the initiative to the knowledge economy’s requirements for new approaches to regulation. The SFT then referred to a number of regulatory realms that would be a part of the reform initiative. These included intellectual property and new life rules, copyright rules, drug approvals, research involving humans, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, a single window for projects such as the northern pipeline, the Agricultural Policy Framework, Canada–U.S. smart border needs, and capital market and securities regulation. The smart regulation initiative found its way into the SFT and thus into a recognized high-priority status due to several pressures and arenas of advocacy. One was certainly the federal innovation strategy paper that had emerged earlier in 2002. Its consultation processes had revealed numerous areas in which business and consumer groups saw current kinds of regulation as obstacles to innovation. There were also some areas where insufficient regulation could be a bar to progress. So the notion that regulation had to be “smart” or “smarter” than in the past certainly emerged from the innovation debate. Of course, there were also separate pressures emerging from the departments and stakeholder groups concerned with all of the more specific areas of regulation cited above. The Chrétien government created the EACSR, composed of individuals drawn from business, environmental, consumer, and Aboriginal areas of interest and knowledge. Following various consultative processes and Chapter 1 41 building on some of its own commissioned research, the EACSR reported in fall 2004. Interestingly, the EACSR report begins by defining what smart regulation is not. It “is not deregulation” because “Smart Regulation does not diminish protection, as some may fear. It strengthens the system of regulation so that Canadians can continue to enjoy a high quality of life in the 21st century. The committee believes that regulation should support both social and economic achievement. . . .”19 When raising the question of the consequences of non-action in smart regulatory reform, the EACSR argues that “without change, [the regulatory system] will limit Canadians’ access, for example, to new medications, cleaner fuels and better jobs. An outdated system is an impediment to innovation and a drag on the economy because it can inhibit competitiveness, productivity, investment and the growth of key sectors.”20 Thus the red-tape and red-flag themes are woven into the EACSR. And when the EACSR asked what was driving the need for regulatory change, it stressed three factors: “First, the speed of modern society has resulted in an explosion of new technologies. . . . “Second, policy issues are increasingly complex. Boundaries between once distinct areas and disciplines have become blurred. . . . “Third, public expectations of government have risen. . . .”21 Then, and only then, does the EACSR go on to define smart regulation in terms of its three characteristics: “Smart Regulation is both protecting and enabling. . . . “Smart Regulation is more responsive regulation. . . . [and] must be self-renewing and keep up with developments in science, technology and global markets. . . . 19External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, Smart Regulation, p. 9. 20 Ibid., p. 10. 21 Ibid., p. 10. 42 Red Tape, Red Flags “Smart Regulation is governing cooperatively for the public interest. . . .”22 With this smart regulation strategy at its centre, the EACSR went on to examine key features of Canada’s regulatory system, along with five case study sectors or realms of regulation, and then made 73 recommendations. Some are cast as immediate actions and others as longer term in nature. A central thrust of the recommendations is greater regulatory cooperation with the United States, especially in situations where there are only small differences in regulations and approaches. The EACSR report is also careful to stress that the public interest in regulatory matters involves both social, health and environmental issues and economic matters. Hence the smart regulation concept embraces both “protecting and enabling,” with “enabling” as the code word for commercialization and new innovative products. “Responsive” means that government needs to be sensitive to businesses and to the competitive situations they face. In turn, governing “cooperatively” connotes the new modus operandi: achieving public purposes through various governance arrangements (as opposed to command and control regulation, as discussed later in this chapter). A subsequent overall report on smart regulation actions and plans highlighted several steps and initiatives that the Liberal government took in its last year in power.23 An external regulatory advisory board was appointed to be a forum for ongoing stakeholder participation. Partly to deal better with interdepartmental regulatory barriers and overlaps, the federal government established a series of “theme” tables to “strengthen our ability to manage regulation, coordinate regulatory renewal initiatives, and inform the regulatory process with up-to-date and critical information that reflects the needs and expectations of Canadians, as well as the concerns of stakeholders.”24 22 Ibid., p. 12. 23Government of Canada, Smart Regulation: Report on Actions and Plans (Ottawa: Treasury Board of Canada, Secretariat, March 2005). 24 Ibid., p. 10. Chapter 1 43 Five theme tables began their work on the following issues: a healthy Canada; environmental sustainability; safety and security; innovation, productivity and business environment; and Aboriginal prosperity and Northern development. This idea of theme tables is a useful one and can help governments address complex regulatory regime issues. However, it tends not to engage ministers in a very direct way, nor does it relate to developed annual agendas per se. The table dealing with innovation, productivity and business environment is intended to help federal departments find ways to “enhance innovation . . . while more effectively meeting social objectives.”25 It was also intended to explore issues such as ways to focus regulatory attention on areas that pose the greatest risk, so as to help reduce the overall regulatory burden. This idea is important, and it is why I argue in chapters 5 and 6 for the establishment of a Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. While the federal smart regulation agenda gained considerable initial momentum in 2003–04 and 2005, the political climate since then has not been as propitious. Given the uncertainties of first a Liberal minority government and now a Conservative one, it is fair to say that the smart regulation agenda may lose some of its momentum. The same result often occurred after the regulatory reform efforts in the 1980s and early 1990s referred to in the next section. Earlier Debates and Assessments of Regulation and Its Reform Space does not permit a full account of past debates and diagnoses of regulation, but a summary of earlier or related key ways of viewing and critiquing regulation is useful. This section briefly surveys regulatory reform, deregulation and re-regulation; the issue of so-called “command and control” versus “incentive-based” and “flexible” regulation; and risk-benefit assessment and management concepts and related issues centred on the precautionary principle. Each issue and development is discussed briefly, as are the key links among them. 25 Ibid., p. 14. 44 Red Tape, Red Flags A major regulatory reform in the 1980s was combined with various actions leading to de-regulation in specific sectors, such as telecommunication and transportation, but also re-regulation in such sectors.26 Focused reform efforts occurred in the mid-1980s under the Mulroney Conservative government and, in milder forms, in the late Conservative government and early Chrétien Liberal government of the 1992–93 period. Both of these efforts sought to reform regulatory decisionmaking processes and to deregulate to some extent. Both also urged government to search for non-regulatory alternatives before pursuing regulation as a policy choice. Economic values and ideas were certainly a part of these reform exercises, but it is fair to say that neither was driven by a full-blown innovation–new economy paradigm that is the focus of this study, and of the “smart regulation” agenda described earlier in this chapter. In the 1980s and 1990s there was a general effort to move from command and control regulation—the approach said to be dominant in the previous four or five decades—to more flexible, incentive-based and performance-based forms of regulation, including guidelines, codes and standards.27 The concept of command and control regulation implied too many and too detailed input-oriented or process-oriented kinds of rule making. It was seen as a one-size-fits-all approach that didn’t reflect the fact that industries, firms, communities and individuals face diverse situations and contexts. There were and still are many reasons for this effort to change the approach to regulation, such as business pressure and budget cutbacks. Incentive-based regulation recognizes explicitly the complex cost and production situations that different firms, industries and consumers face. The growing presence and importance of trade rules has also resulted 26Margaret Hill, “Managing the Regulatory State: From ‘Up’ to ‘In and Down’ to ‘Out and Across,’ ” in Doern, Hill, Prince and Shultz, Changing the Rules, pp. 259–276. 27 See John Braithwaite and Peter Drahos, Global Business Regulation (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2000). Chapter 1 45 in rule making that is premised on regulating outputs and performance rather than on prescribing inputs and processes.28 In the last decade, governments have been leading or encouraging initiatives that, by their very nature, had to rely on non-regulatory and non-statutory processes, and that sought to work patiently through diverse marketplace stakeholders. Several initiatives of this type have been carried out. As I noted earlier, in the 1990s regulation began to be debated more explicitly in terms of risk assessment and risk management concepts, especially in the broad realm of health, safety and environmental rule making. In particular, this trend occurred among a large set of regulators and their clients whose activities are dependent on science-based regulation or on sound science but also on ideas centred on the precautionary principle.29 Federal science-based departments engaged in health, safety and environmental regulation all have basic decision-making frameworks for identifying, assessing and managing risks. However, what does not exist is any cross-governmental institutional process for ranking risks. I return to this point in Chapter 5 in relation to the discussion of the need for a Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. When environmental groups began promoting a precautionary approach, trade regimes began to defend the norm of sound science more vigorously. Trade regimes were often suspicious of precautionary concepts because they feared such ideas could reduce the emphasis on sound science and become the proverbial “Mack truck” clause that would drive right through trade agreements. Precaution implied that some decisions could be made even in the absence of such science, where there were reasonable concerns that observed hazards might produce irreversible effects unless some preventive action was taken. The precautionary principle gradually 28 See Lester M. Solomon, ed., The Tools of Government: A Guide to the New Governance (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2002) and Malcolm K. Sparrow, The Regulatory Craft (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 2000). 29Doern and Reed, Risky Business, Chapter 1. 46 Red Tape, Red Flags appeared in many international protocols and in several federal statutes, such as the Oceans Act, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act and commitments regarding bio-diversity. While each of the above features of regulatory reform, study and practice has been presented as a brief historical portrait, few if any of these issues and debates have disappeared from the scene. Thus, when one implies that the smart regulation agenda, the recent federal Directive on Streamlining Regulation, or some combination of the two is now the favoured paradigm and discourse, it is not clear exactly what it is replacing. The smart regulation paradigm differs from deregulation and earlier reform agendas in that, as we have seen, it is much more informed by innovation agendas and notions about the knowledge-based economy and rapid technological change. But smart regulation does sweep into its conceptual arms many of the basic notions of incentive-based and flexible regulation, and risk–benefit regulation. In these senses it is not replacing earlier concepts; rather, it is complementing them or layering itself on top of them. The Directive on Streamlining Regulation adds the life-cycle approach but otherwise retains the earlier policy add-ons. Conclusion This chapter has set the context for the analysis by examining three key forces that are affecting regulation in the innovation age in Canada and elsewhere, and by exploring the policy context for federal regulation and recent regulatory reform exercises and issues. By its very nature, rapid, complex economic and technological change creates both new products and production processes whose proponents are anxious to find an unencumbered route to market success. However, it also inevitably creates concerns about health, safety and the environment. Chapter 1 47 Consumer demand for increased access to new products is premised on a significant reduction of red tape, but related red-flag concerns are never very far from the surface. My brief discussion of the science-based nature of risk regulation— and, thus, of the overall interactions between regulation and innovation— highlighted the delicate balancing acts involved. Caught up in these complex processes are core concepts such as safety versus risk-benefit, where different notions of what red flags might actually be are central and often not clear cut. The analysis of past regulatory reform initiatives showed how each initiative dealt in its own way, in different time periods, with the core trade-offs between red tape and red flags in specific situations, as well as with the growing integration between red tape and red flags. In the case of the recent federal smart regulation initiative, these core tradeoffs were more explicitly linked to innovation itself and to the growing need for Canada to compete in the knowledge-based economy. Last but not least, the above discussion of federal regulatory policy and the current regulatory decision process and how it evolved through add-on elements of suggested good regulatory practice showed how it had to continuously try managing red-tape and red-flag values, processes and concerns. In the three regulatory regime case studies that follow in the next three chapters, I look more closely at the forces and elements traced in this chapter as they relate to the drug regulation and public health regime, the biotechnology and intellectual property regime, and the energy and environment regime. 48 Red Tape, Red Flags 2 The Pharmaceutical Drugs–Public Health Regulatory Regime: Access and the Common Drug Review O ur first regulatory regime case study analysis centres on the pharmaceutical drugs–public health regulatory regime. This regime of multiple regulators and players deals with the complex full cycle of regulation and regulatory enforcement. In this cycle, drug companies develop new drugs; regulators assess and approve the drugs at the pre-market stage, then monitor them in the post-market stage; and provincial health authorities, private drug plans and the federal government decide whether they will fund these drugs or reimburse people for them. The federal government’s involvement in this last process relates to its role in providing health care directly for people such as military personnel and prison inmates. This chapter begins with an initial broad discussion of the regimelevel interactions of the main regulators and players, and of the inherent red-tape and red-flag choices and pressures involved in the current innovation age, as outlined in Chapter 1. The second section briefly examines the context of the regime and the regime’s evolution in response to criticism over the last two decades, propelled by the three main forces examined in the previous chapter. The chapter then looks more closely but briefly at one example of regulatory regime change, the Common Drug Review (CDR). In this newer phase of the regulatory regime, regulators must face difficult issues of access to expensive new drugs that are focused on small populations who might benefit from such products. Conclusions then follow regarding the regime analysis as a whole. The Regulatory Regime: Core Features The regulatory regime for drug products functions through a set of agencies and processes related to therapeutic products. (See text box titled, “Core Agencies in the Pharmaceutical–Public Health Regulatory Regime.”) I have also included a list of the key stages in the regulatory approval of drugs and in their post-market review and use. (See text box titled, “Main Stages of Pre-Market Drug Approvals and Post-Market Review.”) The stages of the CDR are outlined later in the chapter. Chapter 2 51 Therapeutic products include medical devices, natural health products and drugs, including pharmaceuticals, radiopharmaceuticals, biologics and genetic therapies. In Chapter 3, I will focus on products involving biotechnology, particularly their links to the intellectual property regulatory system. Health Canada defines a drug as “any substance used in the diagnosis, Core Agencies in the Pharmaceutical– treatment, mitigation or prevention of Public Health Regulatory Regime a disease, disorder or abnormal physi­ Health Products and Food Branch of cal state, and in restoring, correcting Health Canada or modifying organic functions in Therapeutic Products Directorate of the humans and animals.” Health Canada Health Products and Food Branch and its agencies function under the Drug companies, and S&T staff within provisions of the Food and Drugs Act drug companies and Food and Drug Regulations. The Networks of health professionals and patients, especially in post-market review Health Products and Food Branch (HPFB) of Health Canada provides Patented Medicine Prices Review Board overall policy and strategic guidance, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health but it is the HPFB’s Therapeutic Canadian Expert Drug Advisory Committee Products Directorate (TPD) that plays the lead regulatory role for drugs and U.S. Food and Drug Agency medical devices. TPD is our initial institutional focus for some key stages of the drug review and approval process, although Health Canada reports on the drug regulatory process often describe HPFB as the entity officially taking action and making decisions. However, the regulatory regime in a larger sense also includes the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB). PMPRB is responsible under its Patent Act mandate for regulating the prices patentees charge for prescription and non-prescription drugs sold in Canada to wholesalers, hospitals or pharmacies for human or veterinary use, to See Health Canada, Access to Therapeutic Products: The Regulatory Process in Canada (Ottawa: Health Canada, 2006), p. 3. Ibid., p. 26. 52 Red Tape, Red Flags ensure that they are not excessive. PMPRB will loom larger in Chapter 3’s analysis of biotechnology and intellectual property, but it also warrants mention in this chapter’s analysis of the pharmaceutical drugs–public health regime. The regime also includes, as Main Stages of Pre-Market Drug Approvals we see in more detail below, and Post-Market Review the Canadian Agency for Drugs Pre-clinical trials and Technologies in Health Clinical trial authorization (CADTH). CADTH develops Regulatory product submission evidence-based clinical and Review of product submission pharmaco-economic reviews to Market authorization decision assess a drug’s cost effectiveness. CADTH is centrally involved in Public access the CDR, which began in 2003 Surveillance, inspection and investigation and which involves a single process to assess new drugs for potential coverage by participating federal, provincial and territorial drug benefit plans. Provincial and territorial health ministries are also part of this regime because they ultimately make regulatory and expenditure decisions about whether a new drug will be funded and listed for reimbursement under medicare services delivered at the point of in-patient care. A more detailed sense of the seven stages of drug pre-market assessment and post-market review can be found in the descriptions of each stage by Health Canada: Pre-clinical trials: These are studies carried out in vitro (using test tubes) and in vivo (using animals) to assess the performance of the drug, including the existence and extent of toxic effects. Clinical trial authorization: HPFB reviews the information sponsors submit in the application to ensure that the trial on humans is properly designed and that participants are not exposed to undue risk. Trials must be conducted in accordance with internationally accepted principles of good clinical practice. This summary is adapted from ibid., pp. 6–23. Chapter 2 53 Regulatory product submission: If clinical trials indicate that a new drug has therapeutic value that outweighs the risks associated with its proposed use, the manufacturer may seek authorization to sell the product in Canada by filing a new drug submission. HPFB submissions typically involve between 100 and 800 binders of data, as well as details on the production of the drug and its packaging and labelling. Such new drugs are commonly referred to as brand-name drugs created by companies that have previously patented them. Companies also submit generic drug product applications to HPFB based on reproductions of brand-name drugs. Review of product submission: HPFB staff screens the submission for completeness and quality; thoroughly reviews the submitted data, sometimes using external reviewers and expert advisory committees; reviews the information that the manufacturer intends to provide to health-care practitioners and consumers; and requests additional information as needed. HPFB may grant priority review status to new drug submissions when the drug is intended for the diagnosis of serious, life-threatening or severely debilitating illnesses or conditions and when one or both of the following conditions exists: no comparable product is currently marketed in Canada; or the new product significantly increases efficacy or significantly decreases risk such that its overall risk-benefit profile is better than that of existing therapies. HPFB sets target times for completing reviews of different classes of products, as discussed in more detail later in this chapter. Market authorization decision: If, after completing a new drug review, HPFB concludes that the benefits outweigh the risks and that the risks can be mitigated or managed, it issues a letter known as the Notice of Compliance (NOC) and a Drug Identification Number (DIN). This allows the manufacturer to sell the product in Canada. If the HPFB finds that the application fails to comply with requirements set out under the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations, it will issue a Notice of Non-Compliance (NON). This notice outlines HPFB’s concerns and usually requests additional information. The manufacturer must respond by a specified date. A manufacturer may 54 Red Tape, Red Flags appeal a decision made by HPFB on a submission. HPFB also operates a Special Access Programme (SAP), which allows health-care professionals to gain access to drugs, natural health products and medical devices that have not been authorized for sale in Canada. Special access can be requested for emergency use, or if conventional therapies have failed or are unavailable to treat a patient. Public access: While SAP is part of overall access, the public access stage mainly involves meeting certain labelling requirements once a new drug has been approved for the Canadian market. For instance, manufacturers must provide drug product monographs that tell consumers what the medication is for, how to use it and what the potential side effects are. Access information is also provided via the HPFB Summary Basis of Decision (SBD). Databases are also available on authorized therapeutic products. This stage also involves the price review of patented medicines process and the CDR (see more below). Surveillance, inspection and investigation: This is the final, or postmarket, stage. Manufacturers are responsible under the law for monitoring the safety of their products and are required to report any new information they receive concerning serious side effects (adverse reactions), including any failure of the product to produce the desired effect. Patients and health professionals are also involved in monitoring and reporting adverse reactions. HPFB also carries out other inspection and compliance activities related to a range of legal requirements. While it is necessary to appreciate the above “stages” portrait as a core drug regime feature, the portrait is not in itself a sufficient or dynamic enough picture of the regime. It does not sufficiently reveal the statutory issues around the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations and their current content and reform needs, as discussed further later in this chapter. Moreover, at the pre-market stage, the core relationships tend to be between drug firms and their S&T staff on one side, and TPD assessors and reviewers on the other. Hence, these relationships are intensely bilateral and detailed. The pre-market stage also involves core internal Chapter 2 55 relations within drug firms and other applicants, as new drug products emerge through internal self-regulation and scientific review. On the other hand, at the post-market stage, the range of players widens enormously, as thousands of patients, health professionals and health institutions become a daily, even hourly, part of the post-market review process, functioning as a complex information and reporting network. At this stage the system also becomes more multi-level in terms of its regulatory governance participants, which include federal, provincial, local and international agencies. Relationships with the U.S. Food and Drug Agency (FDA) are also close and frequent at the technical and regulatory level. This summary of the regulatory regime is important for the analysis in this chapter and in Chapter 3. We need to understand the regime’s complexity and full range of stages, actions and players. However, we also need a complementary assessment of the way this regulatory regime has evolved and the way it was criticized and changed, as the three main forces outlined in Chapter 1 took hold and as red-tape and red-flag challenges diversified quickly in the innovation age. Context, Regime Change and Evolving Criticism The Thalidomide Model and the Pre-Market Safety Focus As in other regulatory realms, specific controversies or crises often influence the drug–public health regulatory regime significantly, leading to path-breaking changes that shift the entire regime’s climate, context and focus. One such change resulted from the thalidomide disaster of the late 1950s and early 1960s. In a sense, this serious regulatory failure and the resulting response caused the federal regulatory regime for drugs to focus, quite naturally and overwhelmingly, on more 56 For analysis, see G. Bruce Doern and Ted Reed, eds., Risky Business: Canada’s Changing Science-Based Policy and Regulatory Regime (University of Toronto Press, 2000), Chapter 1, and Joan Murphy, “Multilevel Regulatory Governance in the Health Sector,” in G. Bruce Doern and Robert Johnson, Rules, Rules, Rules, Rules, pp. 305–324. Red Tape, Red Flags stringent pre-market processes where “safety” was the dominant value. Regulatory mandate statements spoke unambiguously about safety (red flags) and the internal culture of the regulatory regime was, not surprisingly, dominated by this value. All regulatory agencies and regimes have dominant cultures and ways of thinking about and acting on issues. Canada’s drug regulators clearly have had a dominant safety focus. This focus was ingrained in the public discourse even when concepts such as risk–benefit were recognized. In recent years, risk–benefit considerations began playing a stronger role in discourse. However, when cases such as Vioxx emerged in the last couple of years, the ongoing importance of safety as a norm quite validly re-emerged. Exceptional cases are always crucial. However, regulatory regimes must operate in relation not just to these exceptional cases but also in relation to “normal” drug approvals, where a balance between risks and benefits is much closer to the norm and what is actually being sought most of the time. The Backlog Problem and Slow Product Approval Times The problem of backlogs and slow drug approval times began in the late 1980s and continued until well into the early years of the new century. Very early in the 1990s, the business community and other parts of the federal government voiced serious regulatory red-tape concerns. They criticized what was then called the Therapeutic Products Programme (now TPD) for its slow review times and large backlog of unreviewed proposals. However, it took much longer—until about 2005—for Health Canada to deal with the backlog problem. When the backlog problem was solved, attention then focused in part on improving the normal drug proposal review time lines. Here, comparative benchmarking showed that Health Canada’s average review time was still significantly slower than that in other jurisdictions, such as the U.S. and the U.K., but that the gap was beginning to close. For an analysis of change in the late 1980s and 1990s, see G. Bruce Doern, “The Therapeutic Products Programme: From Traditional Science-Based Regulator to Science-Based Risk-Benefit Manager?” in G. Bruce Doern and Ted Reed, eds., Risky Business, pp. 185–207. Chapter 2 57 There was also a related significant regulatory lag. Throughout the 1990s, many recognized that the decades-old Food and Drugs Act and Regulations needed a major overhaul, but this revision had still not occurred as of mid-2007. This delay is discussed further later in this chapter, in the section dealing with the Health Canada Blueprint for Renewal. In the first decade of the new century, the drug regulatory regime was speaking in terms of a more explicit access strategy. The 2002 SFT called for “speeding up the regulatory process for drug approvals to ensure Canadians have faster access to the safe drugs they need, creating a better climate for research on drugs.” The Romanow Commission’s recommendations on Canadian health care strummed a similar theme. As a result, Budget 2003 provided $190 million over five years to fund a Therapeutics Access Strategy (TAS), and a National Pharmaceuticals Strategy also emerged. A further $170 million over five years became available in Budget 2005 to enhance the safety and efficacy of drugs. There were clearly considerable catch-up aspects to these announcements but also a sense of a need to deal with future volumes of new drugs. For example, in 2005 there were 63 new drug submissions but, earlier in the regulatory cycle, there were 1,982 clinical trial applications to HPFB. Not all such trials lead to new drug submissions, but these clinical trial numbers certainly point to a likely need to deal with much higher submission volumes in the future. Higher Volumes of Drugs, New Levels of Access, and the Rebalancing of Pre- and Post-Market Review As a new century emerged, the actual and potential emergence of new biotechnology and bio-health products also increasingly influenced the drug regulatory regime. I discuss biotechnology more fully Quoted in Health Canada, Access to Therapeutic Products, p. 4. Health Canada, Access to Therapeutic Products, p. 12. 58 For discussion, see Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, Biotechnology and the Health of Canadians (Ottawa: Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, 2004). Red Tape, Red Flags in Chapter 3. However, some aspects of new bio-health product volumes and characteristics need to be noted here in terms of how they affected the drug product and related therapeutic product realms. Such products, also labelled as biopharmaceuticals, are therapeutics or preventive medicines derived from living organisms using recombinant DNA technology. Relatively recent global examples include a nasally delivered influenza vaccine and a drug to treat osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at high risk of fracture. However, products range across several aspects of disease prevention and treatment. These products include vaccines, tests that speed diagnosis and enhance patient response to treatment, genetic testing products (see Chapter 3), therapeutic drugs, stem cell therapy products and biologics. These new products and greater product volumes have several implications, but I note here only two: the need to rethink assumptions because more tailored products are aimed at smaller markets than normal pharmaceutical drug products; and the need to rebalance the pre- and post-market assessment aspects of regulation. The notion of more tailored products means that more drugs and devices are now derived from the genome mapping and DNA characteristics of small sub-populations. Typically, most drug products are now aimed at huge target markets, but bio-health products are different.10 However, the extent to which companies create niche-market drugs depends, as we will see in Chapter 3, on the availability of risk capital, especially for the numerous small firms developing these products. Similar pressures, but on a smaller scale, were previously encountered in relation to so-called orphan drugs. These were drugs that would not normally have reached the market because of economic imperatives but which were crucial to smaller sub-markets of patients. The U.S. and the See World Health Organization, Genomics and World Health, Report of the Advisory Committee on Health Research (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002). 10 The Economist, “Pharmaceuticals: Beyond the Blockbuster,” The Economist 383, 8535 (June 30, 2007), pp. 75–76. Chapter 2 59 EU developed special incentives to enable some such products to get to market11 but Canada has no such system. There will be many more such potential orphans in the emerging tailored bio-health product market. This situation also means that a much larger proportion of drugs may not be available in a middle-sized country such as Canada, since the local market may be too small to support the cost of regulatory review. This characteristic is important in its own right, but it is ultimately tied to other features of likely market and patient pressures. As Chapter 1 highlighted, the Internet and the existence of patient lobby groups means that individuals will learn about prospective new bio-health drugs, devices and products, and will exert pressure on national regulators to approve them or to allow them to be imported. One impact of greater volumes of new products is that drug and health regulators may have to make greater use of provisions regarding exceptional circumstances: regulatory provisions that allow faster approval or temporary use of products. These provisions have been used for some AIDS-related drugs and other products, for instance. As noted earlier, Health Canada’s SAP provides access to non-marketed drugs to practitioners treating patients with serious or life-threatening conditions when conventional therapies have failed, are unsuitable, are unavailable or offer limited options. However, the combined logic of the volume and complexity dynamic and the tailored product dynamic is that there may be more and more exceptions or “special access” needs. With these products approved and available in other countries, and likely flowing into middle-sized countries such as Canada (increasing the number of products covered by special access programs), serious questions will likely arise about the value added by the regulatory system, and whether the system is worth the cost. 11 See Thomas Maeder, “The Orphan Drug Backlash,” Scientific American, 288, 5 (May 2003), pp. 70–77. 60 Red Tape, Red Flags The second impact of greater volumes of new products is the need to rebalance the mix of pre-market versus post-market regulation. The current drug-regulation system is still strongly pre-market-oriented, as it largely dates back several decades to the thalidomide crisis. There are aspects of post-market regulation as well, but typically far fewer regulatory regime resources go into this kind of monitoring and reporting activity. One of the broad implications of the current regulatory system is that once drugs are approved and licensed, they are on the market for the long term. But the changed regulatory regime for drug products based on biotechnology will need to rebalance pre-market and postmarket aspects of regulation. Stringent pre-market processes to ensure safety and efficacy will still be crucial, but greater post-market activity is also likely to be needed simply because drug use by actual diverse, larger populations will occur. In addition, closer post-market monitoring will be particularly important in bio-health areas focusing on smaller but more numerous sub-populations. By discovering adverse or unforeseen effects, increased post-market assessment of actual product use, efficacy and impacts is also likely to increase the number of drugs that are recalled or reviewed (see the discussion of Health Canada’s Blueprint for Renewal plans later in this chapter). Concerns are also growing in the regime as a whole regarding regulation of research that leads to new drugs. These concerns include the need to prevent the unintended release of experimental chemicals. Some are concerned that xenotransplantation could make humans susceptible to new diseases originating in donor species. And numerous ethical and other issues are centred on the treatment of donor genetic material for scientific research.12 The 2004 EACSR report also examined the drug review process as one of its five case studies.13 The report stressed the regime’s complex 12 See Claire Foster, “Regulation for Ethical Purposes: Medical Research on Humans,” in J. Abraham and H. Lawton Smith, eds., Regulation of the Pharmaceutical Industry (Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave MacMillan, 2003), pp. 181–194. 13External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, Smart Regulation, pp. 79–88. Chapter 2 61 characteristics and agreed that safety should be the system’s paramount concern, but also argued that review and approval processes, as of 2004, still took too long. The report also highlighted the issue of Canadians’ access to new drugs and the need to improve the regulatory regime to avoid “disincentives for the development of new pharmaceuticals in Canada and lost opportunities for innovation.”14 When comparing Canada’s regulatory capacities to those of the U.S., the smart regulation report argued that “Canada cannot support a review agency as large as the FDA, nor can it afford to carry out drug reviews as extensive as those of its American counterpart. It must be strategic in its use of its limited resources.”15 Further, it said that Health Canada and its regulatory partners needed to look more strategically at international regulatory cooperation, particularly with the U.S. but with others as well. The smart regulation report recommended that Health Canada “focus on determining the areas of the drug approval process for which an independent approach does not contribute to the quality of the decisions or generate a benefit to Canadians.”16 Eventually, responses to these kinds of problems have emerged, but it is important to show how long that has taken. Why were these responses not higher up on someone’s overall regulatory agenda— Health Canada’s or that of the federal government? Taking a decade and more to deal with these issues is simply not good enough, either in the 1990s or in the current decade. I will return to this issue later in my analysis of agendas and in the Conclusion. Health Canada’s Blueprint for Renewal in an Innovation Context The most recent review process has come in the form of Health Canada’s Blueprint for Renewal, an October 2006 discussion document.17 The Blueprint covers both health products and food, but my summary 14 Ibid., p. 79. 15 Ibid., p. 82. 16 Ibid., p. 83. 17Health Canada, Blueprint for Renewal: Transforming Canada’s Approach to Regulating Health Products and Food (Ottawa: Health Canada, October 2006). 62 Red Tape, Red Flags here focuses on the drug regime aspects of it. Health Canada’s own case for renewal is a broadly self-critical admission that its approaches over the past 20 years have been insufficient for the world it has faced for some time. The document stresses that since 1953, the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations have been “largely intended to be a consumer protection statute.”18 Health Canada’s new approaches to regulation have had to deal with five challenges: an outdated regulatory toolkit that is increasingly limited and inflexible in responding to today’s health products and food environment; the regulatory system’s current incapacity to consider a given health product or food through its entire life cycle, from its discovery or development through to its “real world” benefits and risks in the market; the impact of social and economic changes, such as accelerating scientific and technological advances, the rise of transborder health and environmental threats, and a more informed and engaged citizenry; a regulatory system that currently works in isolation from R&D activi­ ties and policies, and those of the broader health-care system; and a regulatory system with insufficient resources for long-term efficiency and sustainability.19 The Blueprint then goes on to discuss each of these challenges and self-diagnosed inadequacies, all of which have been known since at least the early 1990s. Its recommendations and suggestions for change include moving to the following: a product life-cycle approach, under which manufacturers might be required to include pharmaco-vigilance plans in their pre-market submissions; a system where regulatory interventions are proportional to risk, a change that would require revamping the product categorization system; a proactive and enabling regulatory system, which would not only keep pace with trends but which would also be ahead of them where 18 Ibid., p. 6. 19 Ibid., pp. 6–7. Chapter 2 63 possible (partly through greater regulatory foresight programs and activities related to new and changing technologies); a system that makes the best use of all types of evidence, by complementing current pre-market assessments with more extensive post-market monitoring; an emphasis on specific populations regarding patient drug responses, which would include a capacity to deal with new, tailor-made products for diseases that affect smaller patient or genetically specific populations; and an integrated system.20 Other analyses have not been quite so accepting as mine of the innovation- and access-driven logic of the Blueprint and of the previous smart regulation logic.21 They think that logic is influenced too strongly by business pressure, rather than by public health and safety concerns, and that, by agreeing with it, Health Canada is weakening its central and core regulatory mandate. In my terminology, these critics argue that the new logic focuses too much on reducing red tape in the name of speed and innovation and not enough on addressing redflag issues, which are increasing in number and scope. This view also seeks to ensure that pre-market rigour is not sacrificed on the altar of a greater post-market complementary focus in the regulatory regime. Illustrative Regime Change: The CDR, Access and the Drug–Public Health Regulatory Regime Thus far, I have not discussed in any detail another element of the drug regulatory regime: namely, the eventual approval or non-approval of drugs for funding under Canada’s health-care system. More attention has 20 The above list is adapted from ibid., pp. 7–24. 21 See Trudo Lemmens and Ron A. Bouchard, “The Regulation of Pharmaceuticals in Canada,” in J. Downie, T. Caulfield and C. Flood, eds., Canadian Health Law and Policy, 3rd edition (Markham, Ontario: Butterworths, 2007). 64 Red Tape, Red Flags been focused on this element recently because of the establishment of the CDR in 2003 and because of the growing number of new drugs being approved to which Canadians want quick but safe access. I will now look at this area as a particular example of regime change and inertia. I have already noted the basic mandate of two of the agencies, or groups of agencies, involved in this aspect of the regime: CADTH and the provincial and territorial health ministries. I have also referred briefly to the public access stage of the drug regulatory regime and process. CADTH is not a regulatory body. Rather, in the context of the CDR, it develops evidence-based clinical and pharmaco‑economic reviews to assess a drug’s cost effectiveness. These reviews are used by the Canadian Expert Drug Advisory Committee (CEDAC), an independent advisory body of professionals with expertise in drug therapy and evaluation. This committee in turn makes recommendations on which drugs to include in the formularies of the participating drug plans. In more particular terms, the CDR process consists of the following basic stages: the complete submission is received; submission plus information received through independent literature review search is reviewed by clinical and pharmaco-economic reviewers; reviews are sent to the manufacturer for comments; the manufacturer’s comments are sent to reviewers for replies; reviews, comments and replies are sent to CEDAC and participating drug plans; CEDAC deliberates; CEDAC issues its recommendation and reasons for the recommendation to drug plans and the manufacturer; and final CDR reviews are sent to the manufacturer for information.22 22 Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Submission Brief to House of Commons Committee on Health (Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, April 25, 2007), p. 7. Chapter 2 65 The ultimate regulators and decision makers regarding what drugs most Canadians have access to under medicare are the federal, provincial and territorial governments. They include the Quebec provincial government, though it is not a part of the CDR process. The provincial and territorial health ministries examine the CDR process recommendations “but retain the final say over which drugs to include in their respective formularies.”23 In making these decisions, the governments are both regulators and spenders since, if coverage is approved, they are deciding to increase their budgets for these new drugs. According to its mandate, the CDR conducts “objective, rigorous reviews of the clinical and cost effectiveness of new drugs, and provides formulary listing recommendations to the publicly funded drug plans in Canada (except Quebec).”24 Canada’s public drug plans differ, however, regarding the drugs they cover and the populations they serve. Moreover, decisions governments need to make regarding each new drug involve issues and questions such as the following: how the drug compares with alternatives, which patients will benefit, and whether the drug will produce value for money. In October 2005, first ministers directed those involved in the CDR to expand its role by making recommendations “for reimbursement to all drugs and to work towards a common national formulary” so as to eventually produce more consistent access to drugs across Canada.25 Ultimately, a number of aspects of the political economy of health care drive these kinds of aspirations for access to funded drugs.26 One aspect is certainly the notion that national medicare is a right. That has never been strictly true for funded access to drugs. Governments fund access to drugs given to patients in hospitals while they are under treatment there. 23Health Canada, Access to Therapeutic Products, p. 19. 24 Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Common Drug Review [online]. (Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2006.) www.cadth.ca/ index.php/en/cdr. 25 Ibid., p. 19. 26 See Allan Maslove, “Health and Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements: Lost Opportunity,” in G. Bruce Doern, ed., How Ottawa Spends 2005–2006: Managing the Minority (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005), pp. 23–40. 66 Red Tape, Red Flags However, when Canadians are not in hospital, drugs are paid for under any private plans they may have. Secondly, if access to new drugs is seen to be part of what the British refer to as “postal code” health care—where your access to new drugs depends on where you live—political volatility could result. An equal right to medicare is often cast as a crucial feature of Canadian national unity. Thirdly, studies show that drug costs are the fastest growing driver of overall health-care costs and that, in turn, health-care costs are the fastest growing and largest part of provincial budgets. Since the median age of the population is rising, the need for access to health care is increasing relative to earlier post-war demographic periods. A 2004 Conference Board of Canada study concluded with respect to drug costs that: The rate of increase in drug spending has consistently outpaced the overall rate of increase in health care spending since 1984. Total Canadian spending on drugs, estimated at $18.1 billion in 2002, now accounts for 16 per cent of all spending on health care. This is up from 12 per cent in the early 1990s and 8.8 per cent in 1975.27 That ultimately means, for the purposes of the analysis in this chapter, that provincial governments in particular want to promote access to new drugs while also controlling their cost and use. They do so in part by delaying—or ultimately not approving—the addition of some of these drugs to their formularies. Not surprisingly, the CDR can be seen as part of the access aspect of the regulatory system and also as new red tape. It is not unreasonable red tape in the sense that decisions for formulary inclusion do need to undergo a form of new or further drug analysis. This further analysis 27 The Conference Board of Canada, Understanding Health Care Cost Drivers and Escalators (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2004), p. 33. Chapter 2 67 potentially goes beyond what TPD does, by dealing with the further three questions posed under the CDR phase, each of which raises different kinds of red-flag issues for the people deciding which drugs to include in formularies. After its first few years of operation, the CDR has already garnered criticism that it is not performing efficiently nor providing access. The industry lobby group Rx&D, which represents Canada’s researchbased pharmaceutical companies, released an initial evaluation of the CDR in October 2005. It argued that: The evaluation unveils exactly what patient groups and Rx&D feared would happen with this added layer of review of new drug submissions which seems to function with limited or no transparency; further delays in making innovative medicines available to needing patients. . . . In fact, by the time the CDR recommendations are reviewed by federal, provincial and territorial governments, an additional five months, if not more, has been added to the time it takes to get medicines to patients.28 A year later, a further Rx&D evaluation argued that the CDR was acting as a barrier to access. The evaluation compared patient access to new drugs in Canada, Sweden, Switzerland, France and the U.K. It showed that Canada approved only 26 out of 50 drugs (52 per cent), compared to Sweden (82 per cent), Switzerland (80 per cent), the U.K. (76 per cent) and France (58 per cent). Overall, the evaluation concluded that the CDR “has resulted in duplication and delays in listing new medicines” (an average delay of more than seven months) and that “the CDR process is a disincentive for more research and development into new medicines.”29 28 Canada’s Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies. CDR report: patients fail to gain timely access to new medicines. Press release. October 14, 2005. 29 Canada’s Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies. Study Shows Canada’s Common Drug Review is a Barrier to Access to New Medicines for Patients. Press release. December 8, 2006. 68 Red Tape, Red Flags These analysts presented the issue entirely as a red-tape barrier, since in their view all the red-flag concerns had been dealt with at the earlier Health Canada pre-market review stage. A largely similar but more complete view was advanced in a 2007 Fraser Institute assessment.30 The study compared the global wait for the development of new drugs with Canada’s, with Canada’s wait times being an amalgam of the time needed for three processes: marketing approval from Health Canada; reimbursement recommendation by the CDR; and a decision on eligibility for provincial reimbursement. The authors calculated a consolidated average wait time for access to pharmaceuticals and biologics across these three elements, but looked separately at times for each type of product. The study concluded that: The data for the period from 2001 to 2005 suggest that Health Canada’s approval times have improved for pharmaceuticals since 2003 but have gotten longer for biologicals. Comparing the wait internationally (averaged across both biologicals and pharmaceutical medicines, and across all drug submission types) suggests that Health Canada’s performance also improved relative to Europe’s in 2005 but has been longer than in both the United States and Europe in the majority of the five years studied. This segment of the wait for access to new medicines equally affects all patients in Canada, whether they pay for their drugs through private insurance, out-of-pocket expenditure, or public drug programs.31 30 See Brett Skinner, Mark Rovere and Courtney Glen, Access Delayed, Access Denied: Waiting for Medicines in Canada (Vancouver: Fraser Institute, March 2007). 31 Ibid., pp. 1–2. Chapter 2 69 With respect to the CDR’s effect on wait times, the study concluded that: The CDR’s contribution to the wait time for new pharmaceuticals is 257 days compared to 186 days for new biologics. By comparison, the wait for provincial approval of reimbursement adds, on average, another 201 days for pharmaceuticals and another 187 days for new biologics. The total average wait for approval of reimbursement is 458 days for pharmaceuticals and 373 days for biologics. In other words, patients who are dependent on public drug benefits that are delivered only through in-patient settings must wait more than a year after Health Canada has certified a new drug as safe and effective before they have access to it.32 The study also drew attention to the fact that new drugs covered by private insurance are generally eligible for reimbursement as soon as Health Canada has certified they are safe and effective, but that private insurance sometimes has annual coverage limits that might expose patients to significant out-of-pocket costs. Not surprisingly, CADTH sees its red-tape and red-flag record quite differently. In a recent statement to a House of Commons committee, CADTH stressed that: . . . prior to the CDR, the [drug] reviews often took longer, and the level of rigour varied considerably across the jurisdictions. Evidence shows that the total time to formulary listing has not increased since before the inception of the CDR. This is despite establishing a standardized process that has both increased the level of rigour of the reviews and added many transparency elements to the process.33 32 Ibid., p. 3. 33 Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Submission Brief to House of Commons Standing Committee on Health. Ottawa: April 25, 2007. 70 Red Tape, Red Flags CADTH also notes that a recent evaluation of the CDR concluded that “the impact of the CDR on participating drug plans has, according to drug plan representatives, been wholly positive. The drug plan’s perceptions were that the process is rigorous, consistent, and has reduced duplication.”34 The CDR has received 94 submissions to date and issued 68 final recommendations. Drug plan formulary listing was recommended for about 50 per cent of drugs reviewed. CADTH also stresses that drug plans’ decisions have followed CDR recommendations 90 per cent of the time.35 Further aspects of regime development are now underway. The CADTH budget has been more than doubled to $5.1 million so that the CDR can cover new indications for old drugs and CADTH can carry out initiatives to increase transparency. Regulatory politics and concerns related to the CDR and drug access also arise at the individual level and via the lobbying of patient NGOs. For example, the Colorectal Cancer Association of Canada has lobbied hard for cross-Canada funding of the colon cancer drug Avastin, which is currently covered only in B.C. and Newfoundland.36 The drug can cost $35,000 for a course of treatment. Some patients are paying for the drug themselves after failing to obtain coverage in their home province. This kind of highly personalized health-care regulatory and funding politics has also garnered responses from drug companies other than general criticism of regulatory lag. For example, in the U.K., a drug company called Janssen-Cilag has proposed a scheme whereby the U.K. National Health Service (NHS) would pay for a certain drug, which costs £18,000 per patient, only when the drug worked.37 Under the U.K.’s rough equivalent to Canada’s CDR process, it was recommended 34 Ibid., p. 5. 35 Ibid., p. 5. 36 See Joanne Laucius, “Patients Buy Cancer Drugs at New Clinic,” The Ottawa Citizen (June 3, 2007), p. 6. 37 BBC News, “Cancer-Drug Refund Scheme Backed,” BBC News [online]. (June 4, 2007), newsvote.bbc.co.uk/mpapps/pagetools/print/news.bbc.co.uk/1. Chapter 2 71 that multiple myeloma patients showing a full or partial response to the drug after a maximum of four cycles of treatment would be kept on it, with the treatment funded by the NHS. Conclusion This analysis of the pharmaceutical drugs–public health regulatory regime shows the complex nature of the regime, including the stages of drug approval through to post-market review, and the pressures to rebalance the weight given to both pre-market and post-market processes. It conveys regime complexity by describing the number of agencies involved, focusing on the HPFB and TPD in the early decision stages and then listing the wide array of players involved in the postmarket phase, including numerous health professionals, hospitals and patients. The discussion of the CDR then extends the scope of regime agencies to include CADTH, CEDAC and, crucially, provincial health ministries and their processes for approving drugs for reimbursement under medicare and related drug programs. Accordingly, the analysis shows the inherent overall complexities of regulatory regimes. There are multiple agencies and diverse regulatory review cycles and stages, each with its own statutory and related objectives tied to health, safety, risk-benefit, price control and monitoring, and cost-effectiveness concerns. The full regime links and involves federal and provincial governments and drug companies, business interest groups, patient and disease groups, and complex networks of health professionals and individual patients, consumers and citizens. Each of the three forces examined in Chapter 1 has helped shape the nature of the regime and regime change over the past two decades. The speed and complexity of underlying economic and technological changes, and drug companies’ concerns about competitiveness, are evident in the continuous pressure by business to speed up approvals while preserving 72 Red Tape, Red Flags effective health and safety red-flag values, since they are also essential to drug company profitability and market share. Consumer-citizen demands for increased access to drugs was increasingly evident in the time period covered by my brief account of regime change. Due to the Internet and the wider availability of medical and health information, consumers have become increasingly impatient patients. This pressure for access helped create demand for the Common Health Policy and then fuelled criticisms about the sluggishness of its processes for approving funding for those drugs under medicare. At the same time, however, regulators need to engage citizens in diverse ways, including collectively via stakeholder groups, and individually through Internet-based processes and other initiatives. The complex, science-based nature of risk-benefit regulation is evident in the long learning curve underlying debate on pre-market and postmarket elements of this regime. Safety and risk-benefit are evident as overarching norms in the red-flag debate. Good science is crucial at the front-end approval stage to deal with key safety concerns, such as those revealed by classic examples of regulatory failure as in the thalidomide and Vioxx cases. However, more complex risk-benefit values also emerge not only at the approval stage but also at the post-market stage, where even more complex systems of networked, science-based knowledge and intelligence are crucial to dealing with both risks and benefits. The chapter also shows the inherent sluggishness of the government’s response to problems that emerged in this realm, such as backlogs of unreviewed proposals and long drug approval times. That sluggishness is also evident in the slow way Health Canada revealed its Blueprint agenda, which was recognized in 2006 but whose key features were evident as far back as the early 1990s. Parts of the political and bureaucratic arms of the federal government have long been aware of environmental and technological changes and have pressed for a response. But the review system is still not sufficiently aware of the patterns of change to act in a more timely and integrated way. Chapter 2 73 I return to this issue in my conclusions regarding the need for an annual regulatory agenda and for a Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. Overall, the preceding account of the evolution and criticism of the regime shows the continuing presence of the conjoined red-flag and red-tape conundrums, in the context of the demands of the innovation age coming from both industry and consumers/citizens regarding product access and changing views on the urgency and speed of access. 74 Red Tape, Red Flags 3 The Biotechnology– Intellectual Property Regulatory Regime: Access to Genetic Diagnostic Tests T he second regulatory regime case study analysis centres on the biotechnology–intellectual property regulatory regime. This regime of multiple regulators deals with rule making regarding biotechnology and intellectual property (IP), the approval of biotechnology products and the assessment of patents for inventions related to such products. In this chapter, my focus is on bio-health products and related regime issues regarding access to patented genetic diagnostic tests. Due to space limits, the chapter does not deal with biotechnology in food, nor with broader aspects of biotechnology’s use as a major enabling or platform technology in forestry, environmental remediation, and auto parts and other areas of manufacturing. The food aspects of the regime are referred to only contextually and for historical purposes. I do, however, draw again on the discussion in Chapter 2 of the full cycle of drug regulation and regulatory enforcement. This time, the focus is on how major drug and numerous small biotechnology companies develop new bio-health drugs and biologics, and how regulators assess and approve these products in the pre-market stage and monitor them in the post-market stage. Regarding the even earlier-stage patent aspects of the regime, I examine the process of approving patents, the increase in patent application volumes, and the role of patented products in the conduct of mainly publicly funded research on biotechnology and the human genome. Again in this regime, red-tape issues centre on the speed of the linked approval processes in the regime as a whole. In addition, red-tape issues arise when patents, and what some regard as excessive patenting, produce so-called “patent thickets.” These thickets either block public health research, or create significant uncertainties and increase transaction costs, thus harming innovation rather than helping it. Red-flag concerns in this regime revolve around product efficacy and safety, the ethics of product development and use, and protection of the integrity of the Canadian and international patent systems. The chapter begins with a broad discussion of the regime-level interactions of the main regulators, and of the inherent red-tape and red-flag choices and pressures involved. The second section briefly examines the context and evolution of the regime, including problems Chapter 3 77 identified and criticized over the last two decades. The chapter then looks more closely at one example of regulatory regime change and inertia: namely, control over access to patented genetic diagnostic tests. These tests are used to identify and diagnostically assess speCore Biotechnology (Bio-Health) IP cific diseases or susceptibility Regime Agencies to specific diseases, including Canadian Intellectual Property Office conditions affecting very small Commissioner of Patents sub-populations. The number Industry Canada (regarding changes to the of patents for these tests has Patent Act) increased significantly in recent Patented Medicine Prices Review Board years. Conclusions then follow Health Products and Food Branch of regarding the regime analysis as Health Canada a whole. Biologics and Genetic Therapies Directorate of Health Canada Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee Canadian Biotechnology Secretariat World Trade Organization—Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Canada’s Access to Medicines Regime (linked to TRIPS and the Patent Act) Major drug companies and smaller biotechnology firms Genetics clinics, public researchers, family physicians, and patient groups and networks Canadian Institutes of Health Research (granting council rules and funding) Genome Canada (rules and funding) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 78 Red Tape, Red Flags The Regulatory Regime: Core Features This section provides an initial glimpse of the core agencies. [See text box entitled, “Core Biotechnology (BioHealth) IP Regime Agencies.”] I have also listed the key features of the regulatory patent application and product approval cycles. [See text box entitled, “Core Biotechnology (Bio-Health) IP Regime Patent and Product Approval Stages.”] Core Biotechnology (Bio-Health) IP Regime Patent and Product Approval Stages Patent stages and processes: Patent application by corporate, university and individual inventors Examination of patent by Canadian Intellectual Property Office examiners to ensure the product meets the following criteria: newness (it is the first in the world); usefulness (it is functional and operative); and inventive ingenuity (it would not be obvious to someone skilled in that area) Possible patent appeal process and re-examination process, at the request of either the patent applicant or a third party Granting of the patent and its continuation through annual fees Dissemination of the patent by making it public Licensing under the patent through negotiation with the patent holder (the Commissioner of Patents can also order compulsory licensing for public purposes) Biotechnology product stages and processes: Stages similar to the stages outlined for drugs in Chapter 2 Related advisory, non-regulatory review and study of emerging issues and products by the Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee and the Canadian Biotechnology Secretariat, in the context of national biotechnology and innovation strategies Application of research granting body and ethical rules and guidelines Intellectual Property Aspects of the Regime The IP aspects of the regulatory regime are typically the first part of the full regulatory regime that biotechnology firms and other inventors encounter. The term “intellectual property” embraces patents, trademarks, copyright and other IP rights, but in this case study I focus only on the patent aspects of IP. On the advice of lawyers and patent agents, Canadian-owned firms based in Canada and Canadian inventors apply for patents mainly in Canada and in the United States, although they do sometimes also apply for patents in other countries. The patent system is very much influenced by lawyers and patent agents, who both defend Chapter 3 79 the IP system and earn a living from it as intermediaries between firms and inventors and the patent regulator. In Canada, the patent regulator is the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO), with statutory authority for patents residing in the person of the Commissioner of Patents (the head of CIPO) under the provisions of the Patent Act. Patent examiners in CIPO examine patent applications against the three criteria for granting a patent. First, the invention must be new (first in the world). Second, it must be useful (functional and operative). Third, it must show inventive ingenuity and not be obvious to someone skilled in that area. Once a patent is granted, it confers on the holder a monopoly property right of 20 years, provided the patentee continues to register the patent by paying an annual fee. CIPO is funded mainly by such user fees, rather than by taxpayers. Most accounts of the patent system stress the property rights it confers and hence the protection role it plays. But at the core of the IP-patent system is a larger fundamental trade-off between protection and dissemination. Once a patent is registered, the patent office makes the invention public so that others may view it, study it and potentially improve on it through further invention. Most patents are improvements on previous patents. Thus the patent system’s role in innovation turns on both protecting the inventor and rewarding that inventor for his or her ingenuity, and on encouraging subsequent inventors. Another feature of this kind of trade-off has been the role played in the past by compulsory licensing. These requirements, which are now seriously restricted, were based on a view that inventions made and patents granted should benefit consumers and society; thus, if the inventor was not going to turn the invention into a product or process available See G. Bruce Doern and Markus Sharaput, Canadian Intellectual Property: Innovating Institutions and Interests (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000), and P. Drahos and R. Mayne, Global Intellectual Property Rights: Knowledge, Access and Development (Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave, 2002). See Doern and Sharaput, Canadian Intellectual Property, Chapter 2. See also Lester Thurow, “Needed: A New System of Intellectual Property Rights,” Harvard Business Review 75, 3 (1997), pp. 94–103, and Wagner R. Polk, “Information Wants to Be Free: Intellectual Property and the Mythologies of Control,” in Columbia Law Review 103, 4 (May 2003), pp. 995–1034. 80 Red Tape, Red Flags in the market, then others should be able to do so, after paying a licence fee to the patent holder. Licensing certainly exists in the current system, but persons or firms that want to use the patented item or process then have to negotiate with the patent holder. In the end, the patent holder may decline to license the invention. Licensing issues are at the centre of my later discussion of patented genetic diagnostic tests. With respect to innovation, it is important to stress that patents do not themselves produce innovation in the form of actual products and processes available in the marketplace. Innovation of this more complete kind only occurs when firms or entrepreneurs who hold patents can acquire investment capital to get through the rest of the regulatory approval system for products, as well as the manufacturing, marketing and sales stages of the full innovation process. Inventors and firms, and their patent agents, naturally seek speedy approvals of patents. They criticize CIPO if Canada’s system takes longer than other countries’ patent agencies—particularly the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office—to examine and approve patents. Once patents are granted, industry attention regarding red tape and efficiency shifts to dealing with possible patent infringements and hence to enforcement, a process that relies entirely on the courts. Here the regime takes on different characteristics for big and small firms. Large firms, particularly multinational companies, can afford to use the courts, while small firms often cannot. (I discuss the economics of the small-firm-dominated Canadian biotechnology industry, especially in relation to bio-health inventions and products, later in this chapter.) It is crucial to mention two new regulation and rule-making features of the IP-patent regulatory system. The first is that the minister of industry is responsible for changes to the Patent Act. Patent policy staff at Industry Canada advise the minister directly, while staff at CIPO— which has by far the largest core of expertise in the Government of Canada on patent matters—provides indirect advice. The second feature to note is that regulations (as delegated law) under the Patent Act can emerge out of operational issues and challenges at CIPO. If that happens, they are governed by the normal processes of publication in Chapter 3 81 the Canada Gazette and consultation under the provisions of the federal Regulatory Policy. Biotechnology Aspects of the Regime The biotechnology aspects of this regulatory regime emerge at the patent application stage. However, my discussion of biotechnology aspects in this section concentrates more on the subsequent processes for biotechnology product approvals than on patent approval alone. The latter is the regulatory and operational process that assesses and approves products derived from the application of biotechnology before they are allowed on the market. This regime also engages in some forms of post-market review, makes the overriding rules that govern biotechnology, and has key compliance and enforcement responsibilities. In Canada, when the biotechnology regulatory regime focused mainly on bio-food products, it centred on four departments and agencies. They included Environment Canada and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans; however, in bio-food product approval terms, by far the most dominant were Health Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). The largest political controversies for this regime have tended to relate to food. These controversies escalated at the global level due to serious differences between the U.S. and the European Union (EU). Key differences arose in part because of stronger support in the EU for concepts such as the precautionary principle. The net result was that the EU often opposed or was skeptical about biotechnology food products. In these disputes bio-health products initially stood in the background of political consciousness and controversy, relatively speaking. There have been, of course, important health and biotechnology For detailed discussion, see G. Bruce Doern, Inside the Canadian Biotechnology Regulatory System (Ottawa: Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, 2002). See Garbriele Abels, “Experts, Citizens and Eurocrats: Towards a Policy Shift in the Governance of Biopolitics in the EU,” European Integration 6, 19 (2002), pp. 121–141, and Robert Paarlberg, “The Global Food Fight,” Foreign Affairs, 79, 3 (2000), pp. 24–38. 82 Red Tape, Red Flags debates on such crucial ethical issues as cloning, assisted reproduction and stem cell research. New bio-health products were certainly available, but they were initially few in number. But since the mid-1990s, much larger numbers of such products have emerged and are now in the research and regulatory pipeline. I noted this trend in Chapter 2 regarding the drug regime, but other features of this growing volume are highlighted below. The biotechnological regulatory regime now explicitly gives much more attention to including the rule-making realms listed earlier. [See text box entitled, “Core Biotechnology (Bio-Health) IP Regime Agencies.”] These realms include IP bodies, biologics and genetic therapy directorates, human reproduction regulators, research ethics bodies, research granting bodies, and agencies such as the Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee (CBAC) that conduct technologyand ethics-related assessments of these new technologies. The regime also crucially includes, as Chapter 2 has also noted, the governmental regulatory bodies that determine which products and services can be offered and paid for under medicare, and the pricing of pharmaceutical products by government purchasers of drugs—which, in Canada, include federal bodies such as the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. In short, these other regulators and the core bio-food regulatory bodies noted above constitute the full biotechnology (biofood and bio-health) regime. Context, Regime Change and Evolving Criticism Three key developments—all linked to overriding but shifting redtape and red-flag themes and to regulation in the innovation age— provide the context for regime change. These three developments are the explicit location of both IP and biotechnology in emerging federal and provincial innovation agendas; the lobbying of the fast-changing See Martin Bauer and George Gaskell, Biotechnology: The Making of a Global Controversy (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2002). Chapter 3 83 Canadian and global biotechnology industry to modernize the full regulatory regime; and the emerging criticism of the IP patent rights system by interests focusing on public health and global access to patented life-saving drugs. IP and Biotechnology in Innovation Agendas With respect to most industries, the federal government is, in a very real sense, both a regulator and a promoter or enabler of that industry or emerging technology. That is certainly the case with biotechnology. Initially, the biotechnology strategies led by Industry Canada and its predecessor departments focused on broad support of what was then a bio-food-focused industry, particularly through support for R&D. In the late 1990s, the biotechnology strategy focused on a more balanced regulatory and enabling role. CBAC was formed to foster broader public engagement and to advise the government on health, environmental and ethical issues (all red flag in nature). Its mandate ended in May 1997. It must be stressed that CBAC was not a regulator; it was only an advisory body. The Canadian Biotechnology Secretariat (CBSec) supported CBAC but was also the main Industry Canada staff agency supporting the larger federal biotechnology strategy process. CBSec reported to a group of biotechnology assistant deputy ministers and ultimately to a further group of deputy ministers (DMs) whose departments had mandate roles in this field. While CBAC and CBSec certainly advanced the biotech file, it was evident fairly early on that neither the relevant DMs nor their ministers were particularly engaged with the biotechnology file. At best, biotechnology issues on both the bio-food and bio-health sides received only episodic attention. Biotechnology in food rarely resonated with ministers largely because public opinion on bio-food was never robustly supportive. As bio-health issues began to loom larger, more political positives came to be associated with biotechnology. However, even in this domain, biotechnology as an overriding label presented difficulties. Increasingly, 84 See Michael Prince, Regulators and Promoters of GM Foods in the Government of Canada: An Organizational and Policy Analysis (Ottawa: Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, 2002). Red Tape, Red Flags in Canada and in other countries, the promotional or enabling sides found greater political comfort under broader general labels such as the bio-economy. In 2002, biotechnology did find some pride of place in the Liberal government’s innovation strategy. However, it was pitched at a much more general level, grouped with other enabling technologies, such as information technologies and nanotechnology. The formation of Genome Canada provided further visible support for bio-health research. The current Conservative government has essentially closed down the CBSec and CBAC machinery in favour of a new, broader S&T advisory body whose full mandate is still being determined. Thus, the overall strategic place of biotechnology has not been a high-level one but, rather, one that has functioned mainly at the middle levels of the bureaucracy and somewhat more visibly through the public advisory role of CBAC. In this innovation strategy context, federal policy generally supported the growing importance of IP as a crucial feature of innovation. IP was seen as vital to ensuring that Canada’s companies were patenting, and were aware of their patent rights and of the need to patent in the innovation age. Key changes occurred in the 1990s, particularly after stronger patent and other IP rights emerged after the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations that led to the creation of the World Trade Organization and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). In this climate of greater focus on innovation rather than just S&T or R&D strategies, federal policy focused more on indicators such as rates of patenting rather than on earlier focal indicators such as R&D spending as a percentage of GDP. Rates of patenting in the global league tables of industrial development were seen as more output-oriented indicators than R&D. CIPO, with Industry Canada’s strong encouragement, took steps to encourage Canadian firms and inventors to patent more. See G. Bruce Doern, Global Change and Intellectual Property Agencies (London: Pinter, 1999). For discussion, see Doern and Sharaput, Canadian Intellectual Property. Chapter 3 85 Industry Pressure and Fast-Changing Biotechnology Industry Dynamics The core pressure for change in the regulatory regime came from the biotechnology industry, which lobbied hard to ensure that its member bioeconomy firms could survive and prosper as they developed new technologies, inventions and products. Any discussion of this industrial pressure must be set in the context of the structure of the biotechnology industry and how rapidly its composition has changed in the last few years. In 2005, Canada’s 490 biotechnology companies invested over $1.5 billion in R&D and generated revenues of $3.8 billion. The $15.3 billion in market capitalization of Canada’s public biotechnology companies is second only to that in the United States. The industry stresses its uniqueness regarding the amount of time and financial resources needed to fully develop a new product. This view has shaped not only its view of the combined IP and biotechnology products regulatory regime that it must traverse but also of other rules and provisions embedded in tax laws, such as the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) tax credit program. Since 46 per cent of the Canadian biotechnology industry consists of firms involved with bio-health therapeutics, BIOTECanada, the industry lobby group, has focused its criticism of the regulatory regime on the Biologics and Genetic Therapeutics Directorate at Health Canada in an effort to reduce the submission backlog and improve approval times. Some improvements have occurred in relation to these key industry concerns in recent years. As noted in Chapter 2, the industry has also been very critical of the CDR phase of the drug regulation system, a phase important to bio-health product companies. Several other dynamics of the industry need to be highlighted. First, in some respects, the biotechnology sector is not yet a full-fledged industry, as a majority of its firms do not yet have actual products to sell. Because so many of its bio-health firms are still in the R&D and regulatory approval stages, it is often better to refer to biotechnology as 86 BIOTECanada, BIOTECanada Submission to Pre-Budget Consultations 2007 (Ottawa: BIOTECanada, September 5, 2006). Red Tape, Red Flags a technology platform.10 A recent Ernst and Young study of the industry showed it to be both dynamic and vulnerable.11 A second feature is that the industry is awash in fast-changing corporate restructuring as new sub-sectors of the industry emerge, including integrated bio-pharma companies, contract research companies, drug discovery companies and diagnostic companies. It must also be stressed that virtually all the 490 or so Canadian companies were founded in the last decade. The industry is essentially dominated by small and medium-sized firms with limited cash flows to survive the high front-end R&D and regulatory costs. These shortages in risk capital are likely to be even greater as the issues of high volume and tailored niche products discussed in Chapter 2 affect the regulatory and production pipeline. The bio-health industry lobby strongly argues that the regulatory regime is much wider than the drug or product approval process. Access to patients and to the managed medical market requires attention to all aspects of rule making and rules that affect products. These aspects include IP regulatory processes and capacities in the new high-volume context, but they also extend, as we have seen in Chapter 2, to drug formulary processes largely controlled by provincial governments in Canada but also by the federal Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. The industry has argued that market forces increasingly require nationally and internationally efficient and effective regulatory regimes. The high proportion of international alliances among smaller and larger firms has also been linked to this argument. In a 2004 discussion paper on regulatory performance, BIOTECanada argued that “the rest of the world is outstripping our efforts to develop this technology and Canada will quickly find itself lagging behind countries throughout the world 10 See The Conference Board of Canada, Biotechnology in Canada: A Technology Platform for Growth (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2005). 11 Reported in Roberto Rocha, “Canadian Biotech Industry Remains Volatile: Report,” The Ottawa Citizen (April 17, 2007), p. D1. Chapter 3 87 who are establishing long-term programs aimed at financial and regulatory security for their burgeoning biotech interests.”12 In the field of biotechnology, governments have never automatically marched to the drum of such industrial lobbies. There is considerable inertia involved as they take into account alternative points of view. These alternative views come from NGOs opposed to biotechnology (particularly bio-food) or insistent on appropriate public interest and stewardship standards of regulation and regulatory processes. Such pressure has certainly been present in Canada and, indeed, such NGOs have been given explicit arenas, such as CBAC, for expressing their concerns. Moreover, the regulators themselves—armed with complex statutory mandates and duties—have never simply done the bidding of the industry. IP Rights, Public Health and Global Access to Patented Life-Saving Drugs As noted earlier, the global and national IP systems have focused on the protection side of the core protection-versus-dissemination tradeoff inherent in IP, especially patents. But after the Doha trade negotiations began in 2001 and as criticisms emerged, the focus turned more toward the dissemination side and, hence, to the “public good” side of knowledge and invention. In an overall sense, patents cover all inventions, whether they are new bottle top widgets or new drugs. But of course, in human terms, these products are not all alike in their social importance. A key manifestation of this shift came in the realm of public health access to patented life-saving drugs. At the WTO, this concern emerged through changes to the TRIPS agreement that were intended to create greater access to medicines by WTO member countries with little or no pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity, by allowing them to make effective use of the compulsory licensing allowed under TRIPS. In 12 BIOTECanada, Strained at the Leash: A Discussion Paper for Improving Regulatory Performance for Biotechnology (Ottawa: BIOTECanada, July 2004). 88 Red Tape, Red Flags Canada, these changes took the form of Canadian legislation to create Canada’s Access to Medicines Regime by amending the Patent Act.13 Under the provisions of TRIPS (Article 31), compulsory licensing or government use of patents is allowed without the authorization of the patent owner under certain conditions—for instance, when such use is predominantly for the supply of the domestic market. However, TRIPS also prevents WTO members with manufacturing capacity from issuing compulsory licences “authorizing the manufacture of lower-cost, generic versions of patented medicines for export to countries with little or no such capacity.”14 In 2003, WTO members agreed to a waiver regarding this provision whose purpose was to “facilitate developing and least-developed countries’ access to less expensive medicines needed to treat HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and other epidemics.”15 Canada was the first country to announce that it would implement this waiver. In May 2004, Canada’s legislative framework was given parliamentary approval, and a year later its regulatory provisions came into force. Nonetheless, since then, the Canadian Access to Medicines Regime has “not resulted in the export of any eligible pharmaceutical products to eligible importing countries,”16 nor have any occurred in other countries with similar waiver regimes. Some critics have blamed Canada’s failure to meet the red-flag goals of access to needed medicines on the red-tape provisions inserted at the industry’s insistence into both the amended Patent Act and its accompanying regulations.17 The Canadian access regime contained a statutory requirement that a parliamentary committee formally review the access regime in two years. This review is now nearing completion. In this chapter, I am not 13 For discussion, see Health Canada, Canada’s Access to Medicines Regime: Consultation Paper (Ottawa: Health Canada, 2006), and Lisa Mills and Ashley Weber, “Access to Medicines: How Canada Amends the Patent Act,” in G. Bruce Doern, ed., How Ottawa Spends 2006–2007: In From the Cold—The Tory Rise and the Liberal Demise (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006), pp. 229–246. 14Health Canada, Canada’s Access to Medicines Regime, p. 1. 15 Ibid., 1. 16 Ibid., p. 2. 17Mills and Weber, “Access to Medicines,” pp. 242–244. Chapter 3 89 concerned with the details of this provision or the regime’s current review. Rather, I cite it as an important indicator of evolving criticism of the patent system.18 Both the WTO’s waiver and later permanent amendment on this matter, and the Canadian regime to implement it, were motivated by broad and wholly desirable foreign and international development and health policies. But the policy of access, backed up by legislative and regulatory change, also had to ensure that Canada was still complying with its international obligations under TRIPS and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), was respecting the integrity of its own patent law, and was responding to the competing industry and NGO interests involved in this issue. The access to medicines debate was only one facet of the underlying critique of the patent regime. There was also criticism related to excessive patenting, the ease of getting patents for questionable inventions, and the rise in some fields of patent thickets that were harmful rather than conducive to innovation. These aspects and their links to biotechnology are best seen through the discussion that follows regarding patented genetic diagnostic tests, but the criticisms are by no means confined to this sector. Illustrative Regime Change: Patented Genetic Diagnostic Tests and the Biotechnology–Intellectual Property Regulatory Regime Concerns have emerged about the effects of granting IP rights over human genetic materials in the health sector.19 A recent particular 18 For information on broader global issues, including recent decisions by Thailand and Brazil to overrule patents, see “Pharmaceuticals: A Gathering Storm,” The Economist 383, 8532 (June 9, 2007), pp. 73–74, and Oliver Mills, Biotechnological Inventions: Moral Restraints and Patent Law (Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate Publishing, 2005). 19 See Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, Human Genetic Materials, Intellectual Property and the Health Sector (Ottawa: Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, 2006), and Health Canada, Human Genetics Licensing Symposium (Ottawa: Health Canada, 2007). 90 Red Tape, Red Flags manifestation of these concerns has arisen in relation to control over access to patented genetic diagnostic tests. Several high-profile cases triggered these concerns, when patent holders exercised their rights in ways that many felt harmed the provision of health services and innova­ tion by impairing access to patented genetic diagnostic tests in areas of public health research. A related concern centred on the potential for patent holders to charge excessive prices for their products or services, thereby imposing heavy cost burdens on the health system. One such case involved Myriad Genetics. Ontario and several other provinces objected to the way the firm exercised its patent rights and called for the inclusion of a compulsory licensing provision in the Patent Act. An Ontario report argued that such an amendment “should not obligate the provinces to first negotiate with patent holders for a licence.”20 Section 19 of the Patent Act does not require a priori negotiation where the use is public and non-commercial. The President of the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists points out that the demand for these testing services is increasing “as the number of disease genes identified and the number of tests offered in North America increases….Genetics was once considered an esoteric speciality that did not affect the services provided in other parts of the hospital. Even five years ago, most referrals to labs came from genetics clinics and specialized doctors. . . . Now there is an increasing trend for referrals to come from family physicians and a wider variety of specialists.”21 Because of these concerns, Health Canada and Industry Canada asked CBAC to review these linked biotechnology–IP regime issues in 2004. CBAC in turn asked an expert working party to examine the issue, and that body presented its report to CBAC in August 2005. CBAC then sought further input from stakeholders and issued its own views of the matter. 20 Quoted in Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, Human Genetic Materials, Intellectual Property and the Health Sector, p. 9. 21Diane Allingham-Hawkins, “Addressing Challenges to Providing Medical Genetics Services,” in Health Canada, Human Genetics Licensing Symposium, p. 9. Chapter 3 91 CBAC agreed overall with the expert working group’s main twolevel approach to dealing with the problem, expressed as “prevention” and “remediation”: Prevention. Modify the patenting process to reduce the potential for abuse, by preventing patents from being issued that grant too-broad IP rights; establish guidelines for licensing of IP rights under patent that promote behaviour consistent with the public interest and that are fair to the patent holder; and provide statutory exemption from claims of patent infringement for certain uses of patented inventions. Remediation. Provide statutory remedies for dealing with cases of abuse; and use market regulatory measures and competitive methods for increasing bargaining power to meet certain objectives, such as moderating process of products and services.22 CBAC itself then went on to comment on other key issues in the debate, including some areas where it disagreed with the expert panel. A summary captured some of the red-tape and red-flag issues involved in relation to the larger dynamics of innovation already noted earlier in this chapter: CBAC agreed that the patent regime should be improved to broaden the opportunities for mutual advantage, to deal more effectively with any undesirable consequences of the exercise of patent rights, and to improve the timeliness and transparency of patent processes. CBAC agreed that human genetic materials should not be excluded from patentability on ethical grounds and that to do so “would set Canada apart from other countries, including its major trading partners.” It argued that these and related concerns could be dealt with “outside the patenting process.” CBAC concurred with the main thrust of the expert panel’s opposition to “excluding diagnostic methods from patentability or providing an exemption for their clinical use—actions which could seriously slow innovation in this field,” but then suggested other enhancements to the IP system. 22 Ibid., p. 2. 92 Red Tape, Red Flags CBAC agreed with the expert panel’s views of sections 19 and 65 of the Patent Act. These provisions allow governments and other potential licensees to apply to the Commissioner of Patents to use patented inventions without the permission of the patent holder, when they have been unable to secure licences on reasonable terms. Since neither governments nor other potential licensees had apparently used these provisions, there was no evidence that they were inadequate. Accordingly, CBAC agreed with the panel that there was no need to reintroduce a general compulsory licensing provision in the Patent Act. However, CBAC added that other steps should be taken to enhance sections 19 and 65 of the Patent Act.23 These enhancements included developing clearer definitions of “government use,” clarifying the criteria used to test the reasonableness of patent holders’ terms and conditions regarding licences, and addressing other definitional issues.24 Canadian discussions of these issues have also been linked to the work of international bodies such as the OECD. The OECD is not a regulatory body, but its review and discussions of biotechnology–IP regime issues have focused on closely related “soft law” instruments, such as guidelines and best practices. This work led it to elaborate Guidelines for the Licensing of Genetic Inventions.25 National experts developed these guidelines after consulting with a wide range of stakeholder groups across the biotechnology–IP regime spectrum. As one OECD official put it, “permeating the Guidelines is the idea that innovation is well served by a wide availability of technology, research and information.”26 But as soft law, the guidelines are clearly more exhortative than regulatory. Several concerns were at play in the OECD process. 23 Ibid., pp. 3–4. 24 Ibid., pp. 9–10. 25Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Guidelines for the Licensing of Genetic Inventions (Paris: OECD, 2006). 26 Christina Sampogna, “The Licensing Guidelines Project and Biotechnology IP Initiatives at the OECD,” in Health Canada, Human Genetics Licensing Symposium, p. 17. Chapter 3 93 One concern related to excessive information sharing. Thus, the guidelines call for parties to come to an explicit agreement on the release of information that balances the public interest in speedy dissemination (red tape) with the parties’ interest in IP protection (red flags). The guidelines reflected another concern by encouraging appropriate access to, and use of, genetic inventions to address unmet and urgent health needs, including those in developing countries. However, no definition of these possible unmet and urgent health needs could be agreed on. The guidelines also address concerns about research freedom. These concerns centre on licensing from the private to the public sector, where overly restrictive confidentiality clauses may stifle research and research diffusion—either through actual restrictions or uncertainty about such restrictions. Last, but hardly least, in this debate are issues regarding commercial development. A very big challenge in getting a genetic product or service to market is that of negotiating multiple licences. The guidelines encourage the exploration of mechanisms such as patent pooling and standardized licensing agreements. The ultimate front line of these combined biotechnology–IP regulatory and soft law issues is occupied by patients and medical clinicians, with the latter serving as the mediator between patients and laboratories. As Barbara McGillivray observes, “case studies reveal the vulnerability of patient and patient family interests in the rollout of genetic health technologies and genetic testing in particular. As with public trust in scientific research, there is a question as to whether patient, community and public trust in genetic services [is] being maintained.”27 Health-care providers seek to provide clinically useful tests. But the Myriad case referred to earlier resulted in unequal front line healthcare delivery. In British Columbia, for example, testing stopped due to Myriad’s threat of litigation. As McGillivray further observes, “overnight, the price of a test became $3,800 for initial cases, and, if a 27 Barbara McGillivray, “Balancing Industry and Health System Interests in Genetics Research and IP,” in Health Canada, Human Genetics Licensing Symposium, p. 44. 94 Red Tape, Red Flags mutation was found, an additional $500 per family member. . . . This immediately separated families into haves and have-nots. Few people took Myriad’s test, even though it had the advantage of producing much faster results. Testing was not resumed under the public system for two years.”28 The above example, along with others that could be cited, tests a key aspect of the normative thrust of the OECD guidelines. As we have seen, the guidelines favour access, but access itself is an ambiguous concept. As Fiona Miller points out, access “encompasses at least four dimensions: availability (what technology is ‘out there’); attainability (including local capacity for delivery); affordability; and quality.”29 She notes as well that the patent regime itself “introduces a bias for the distribution of patentable inventions, e.g., a (patentable) vitamin A analogue instead of (unpatentable) vitamin A.”30 An even broader view of the hard law and soft law aspects of the biotechnology–IP regime is found in the work of Richard Gold of McGill University. Gold argues that the patent system goal of encouraging innovation “is subverted by patent thickets where individuals with relevant and necessary patents block research. Despite claims that patents are necessary (to innovation) there is very little concrete evidence, especially in the biotechnology field, that patents either help or hurt the rate of innovation.”31 He notes, however, that clinical diagnostics are an exception to this argument. Gold stresses that one hard law option would be to amend the Patent Act to include a specific discretionary licensing provision for health-care applications. Doing so would not recreate a compulsory licensing provision, such as the one that existed before industry succeeded in getting rid of it. However, the above discretionary compulsory licensing provision could provide a credible threat and might lead firms to modify their behaviour. 28 Ibid., p. 44. 29 Fiona Miller, “Licensing Guidelines and Health Policy in Human Genetics,” in Health Canada, Human Genetics Licensing Symposium, p. 24. 30 Ibid., p. 24. 31 Richard Gold, “The Uptake of OECD Guidelines in Canada,” in Health Canada, Human Genetics Licensing Symposium, p. 22. Chapter 3 95 Gold also rightly points out that, within the realm of soft law, options also range from hard to soft. Any range or part of the continuum of rule making involves different degrees of legitimate coercion. As an example of a “harder” soft law or rule, the three federal granting councils could attach a binding set of IP management obligations regarding the funding of grants. The issues surrounding genetic diagnostic tests are not the only ones leading to increasing criticism of patenting and the patent system. A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision has raised the strong likelihood that excessive patenting and the ease of patenting dubious “inventions” may be seriously reined in, both in the U.S. and in other countries. The case before the U.S. Supreme Court dealt with a patent dispute that centred on the addition of electronic sensors to car accelerator pedals. The court ruled that the combination of the two existing technologies was not sufficiently “non-obvious” to warrant a patent.32 A series of earlier Supreme Court cases resulted in similar judgements, making it more difficult to obtain a patent. Different interests have for some time been calling for stricter standards on patenting, especially regarding the non-obvious criterion. These interests include some industry associations that have sought ways to thwart frivolous lawsuits by “patent trolls”—firms that make a living out of suing others for violating questionable patents.33 Relative to a decade ago, more voices are now critical of, or skeptical about, the automatic positive link between patenting and innovation. These voices are much more prepared to argue that some forms and degrees of patenting are, in fact, a damaging form of red tape and, thus, are harmful to innovation and to the public nature of invention and knowledge transmission, in biotechnology and other commercial fields. 32 “Intellectual Property: Patently Obvious,” The Economist 383, 8527 (May 5, 2007), p. 70. 33 Ibid. See also Don E. Kash and William Kingston, “Patents in a World of Complex Technologies,” Science and Public Policy 28, 1 (2001), and Sunil Kanwar and Robert Evenson, “Does Intellectual Property Spur Change?” Oxford Economic Papers, 55, 2 (2006). 96 Red Tape, Red Flags Conclusion This chapter examined core features of the Canadian biotechnology (bio-health)–IP regulatory regime, both by commenting on how various interests, experts and institutions have assessed its evolving changes, and by looking closely at the issue of access to patented genetic diagnostic tests. As stressed from the outset, the chapter has not dealt with the bio-food aspects of the full regime or with even broader aspects of biotechnology—which, as a major enabling or platform technology, is used in forestry, environmental remediation, and auto parts and other areas of manufacturing. I have referred to the food aspects of the regime only contextually and for historical purposes. Thus, the significant complexities of the full biotechnology–IP regime are by no means fully captured here. Both the biotechnology and patent aspects of the regime, and their interactions and collision points, reveal important elements of innovation policy. Both biotechnology and patenting are seen as crucial to a modern innovation agenda, and overall Canadian policy has embraced them as such during the past two decades. Both reveal the diverse, complex ways in which red-tape and red-flag issues, tensions and role reversals emerge. Industry initially raised red-tape concerns regarding backlogs at the CIPO patent examination and Health Canada product-approval stages, and regarding the need to improve the efficiency of the approval process. Improvements have occurred but very slowly—too slowly, given that the Canadian biotechnology industry is made up largely of small and middle-sized firms. These companies generally have limited financial resources to play the long game of regulatory survival and eventually create successful products, while facing the demands of global competition. Red-tape concerns also emerged from other players in the case of access to patented genetic tests. Here the concern was partly that patents themselves, as well as excessive patenting or the emergence of Chapter 3 97 patent thickets, were harming the public health research process and hindering access by medical practitioners and their patients to new and improved genetic tests. On the red-flag side of the innovation era regulatory equation, this chapter has shown the logical flipside of the red-tape issues. Initially, NGOs and others were concerned that both the patent exam­ination and biotech approval processes were not robust enough to guarantee the safety, health and efficacy of biotech products. There were also growing ethical concerns about biotechnology. Later, as the biotech focus shifted to large volumes of new bio-health products, the red-flag concerns of these groups shifted to interest in getting quick access to all biotechnology products, including new genetic tests. The red-flag concerns of industry were initially much more muted. Of course, industry wanted an effective and safe regulatory system for biotech products, and it knew that governmental regulatory approval was essential to the market value of, and public trust in, its products. In the genetic tests realm, some of industry’s red-flag concerns centred on sustaining the integrity of the patent system and its protection role. The industry also argued that solid patent protection was essential to ensuring that Canada had a strong innovative economy. The three core forces examined in Chapter 1 have emerged strongly and interactively in the evolution of this regime. Arguably, biotechnology is the best example of an industrial sector strongly affected by the speed and complexity of technological change, particularly due to the mapping of the human genome in the last decade. Even more than in the case of drugs, as discussed in Chapter 2, consumer demand for rapid access to new life-saving products and processes has influenced the evolution of bio-health products, including genetic diagnostic tests. The complex S&T and risk-benefit aspects of regulation also emerge strongly in the intense and more in-depth arguments now emerging about whether patenting is conducive to innovation or whether it can actually harm it in certain circumstances. 98 Red Tape, Red Flags With regard to the issue of agenda setting, this chapter shows how neither the policy nor the regulatory aspects of IP or biotechnology ever regularly engaged ministers and politicians. The various biotechnology strategies and the CBAC machinery were useful, but they were also several steps removed from high-level consideration in any continuous way. The federal government has now abolished CBSec, its internal secretariat, and seems to have folded CBAC into a larger and as yet undefined S&T advisory body. So far, the discussion of genetic diagnostic tests has taken place mainly in middle-level bureaucratic and policy community circles centred on CBAC, but CBAC itself has been seemingly neutralized or downgraded in the current federal government’s S&T and innovation policy and regulatory architecture. Chapter 3 99 4 The Energy–Environment Regulatory Regime: Environmental Assessment of Energy Projects O ur third and final regulatory regime case study deals with the energy–environment sector, a realm that involves the work of upwards of 30 regulatory bodies in Canada, including at least five federal ministers and their departments. In this complex regulatory regime, at the operational level, the focus shifts from a direct emphasis on products, as in the previous two chapters, to one on energy projects, such as pipelines, new or extended refineries, offshore developments, electricity grids, and hydroelectric dams and facilities. Of course, “product” is ultimately involved as well, since all projects are related to the supply and transportation of energy sources, products and services that range from oil and gas, coal, electricity, nuclear power and uranium, to renewable fuels and sources, such as wind and solar sources, biomass, ethanol and hybrid fuels, and hydrogen fuel cells. The regime is also intricately involved in projects and products tied to exports of energy, especially to the United States, and hence also to energy and environmental regulators in the U.S. and elsewhere under key agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol. On the environment side of the regime, rule making, compliance and enforcement relate to the environmental impacts of energy production and use by consumers, by firms in all industries, and by governments and thousands of public sector organizations. Rule making has focused historically on issues ranging from lead in gasoline, fuel additives, nuclear reactor safety and long-term nuclear fuel waste storage, and fuel efficiency and emission standards in vehicles and appliances, to complex and wide-ranging concerns about climate change, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and endangered species. The environment side of the regime is clearly project-related, but it is also spatially related. Therefore, because ecosystems are involved, it crosses normal political jurisdictions, be they federal, provincial, local or international. For many years, environmental regulation focused on socalled “end of pipe” pollution and emissions control for air and water. However, from the mid-1980s on, environmental regulators became concerned about sustainable development, a policy and regulatory paradigm focused on preventive action—action that would ensure that the environment would be in a least as good a condition for the next Chapter 4 103 generation as it was for the current generation. This kind of regulation is even more complex and is also clearly characterized by debates about the nature of science-based regulation, where the hazards being assessed are ever-more interrelated. Like previous case study chapters, this chapter begins with an initial broad discussion of the regime-level interactions of the main energy–environmental regulators and of the inherent red-tape and redflag choices discussed in Chapter 1. The second section briefly examines the context and evolution of the regime as earlier problems with it were identified and criticized over the last two decades. The chapter then looks more closely at one example of regulatory regime change: namely, environmental assessment laws, regulations and processes as they relate to energy projects. Conclusions then follow. The Regulatory Regime: Core Features The section includes a list of the key agencies of the energy– environment regime. (See text box entitled, “Core Energy–Environment Regulatory Regime Agencies.”) I have also noted the key aspects of process and of project approvals. (See text box entitled, “Core Energy– Environment Regulatory Regime Project and Related Processes.”) The sectoral energy aspects of the regime refers to a set of regulatory laws, agencies, values, interests and processes that govern energy as a vertical industrial sector. The core of this system of rules consists of the federal and provincial energy boards. At the federal level, the National Energy Board is joined by the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission and by the other federal agencies, such as the Nuclear Waste Management Organization, and the offshore energy joint management bodies and agreements between the federal government and Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. 104 See G. Bruce Doern and Tom Conway, The Greening of Canada: Federal Institutions and Decisions (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), and Glen Toner, ed., Sustainable Production: Building Canadian Capacity (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006). Red Tape, Red Flags Core Energy–Environment Regulatory Regime Agencies National Energy Board Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission Nuclear Waste Management Organization Natural Resources Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans Transport Canada Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Environment Canada Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada Provincial and territorial environmental assessment agencies Provincial independent electricity system operators (such as in Ontario and Alberta) U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission North American Electricity Reliability Organization North American Electricity Reliability Council International Energy Agency Major Projects Management Office (recently announced) Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency International Atomic Energy Agency Provincial and territorial energy boards Commission on Environmental Cooperation and other energy provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement Provincial and territorial environment ministries Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change The sectoral aspects of the regime necessarily extend to the federal and provincial-territorial parent energy ministries (variously titled) where political control is centred and where ministers typically hold some share of the rule-making power with the regulatory board. At the federal level these parent ministries extend beyond Natural Resources Canada to Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), which has some key responsibilities in the North. The other key feature of the energy sectoral regime is that the core energy boards have historically dealt with an industry that had natural monopoly features. Hence, regulation was seen as a substitute for markets to protect consumers but also, quite importantly, citizens as consumers of an essential service industry. Some of these monopoly features have begun to break down in the last two decades because of new energy technologies, but also because of more market-oriented Chapter 4 105 Core Energy–Environment Regulatory Regime Project and Related Processes Energy (sectoral) aspects: Federal, provincial, territorial and Aboriginal energy board hearings on pipelines, and land and offshore energy projects National Energy Board processes regarding gas prices and adequacy of national supply and reserves Energy board dispute resolution processes Nuclear safety assessment processes for new reactors or reactor problems and refurbishment Nuclear waste disposal review and site selection processes Energy emergency and supply rules and processes under the International Energy Agency and the North American Free Trade Agreement Electricity reliability review and emergency processes Security agency and energy agency processes for ensuring security of energy installations Environmental (horizontal) aspects: Periodic hearings/processes for product quality (lead in gasoline; gas additives) CEAC and provincial environmental assessment processes on projects via screening, comprehensive study, mediation, and assessment by a review panel Federal and provincial sustainable development strategy processes and auditing and reporting International convention and protocol-setting processes (e.g., Kyoto Protocol) Citizen-triggered environmental complaints under the NAFTA Commission on Environmental Cooperation ways of thinking about how to regulate more flexibly, keeping efficiency and choice more clearly in mind for at least some consumers. The regime is intended to serve both firms and consumer-citizens. Since it is mainly private firms that ultimately deliver energy products and services, the regulators not only regulate such firms but also have obligations and commitments to such firms. In particular, the regulators have to be conscious of these firms’ ability to raise capital, which also requires firms to have the capacity to earn a reasonable rate of return 106 See Donald N. Dewees, “Electricity Restructuring in the Provinces: Pricing, Politics, Starting Points and Neighbours,” in Burkard Eberlein and G. Bruce Doern, eds., Governing the Energy Challenge: Germany and Canada in a Multi-Level Regional and Global Context (manuscript under review), Chapter 4. Red Tape, Red Flags on investments. As the energy sector has become more market-oriented but still not a fully competitive market—in effect, a managed market— the structure of firms (and therefore interests) within the purview of sectoral regulatory boards has become much more complex. As recently as the early 1990s, the typical energy regulator would deal with a small set of very large firms. In the early 21st century, such regulators must deal with some very large players but also with numerous new, and typically smaller, incumbent firms or firms seeking entry. That is especially the case in restructured electricity markets, but it also is true for the oil and gas and alternative energy industrial sub-sectors. The horizontal environmental aspects of the energy–environment regulatory regime refers to a set of regulatory laws, agencies, values and processes that govern energy from a horizontal perspective. In this area, energy is simply one among many industrial sectors governed by rules regarding environmental matters but also health, safety, fairness, and the quality of products and services, including the nature and quality of competition. This is also a vast and complex terrain. This aspect of the regime is horizontal because it typically applies across the economy and society, in a sense, regardless of sector. A proper institutional mapping of this regime would necessarily include not only particular environmental regulatory bodies and departments, federal and provincial, but also ministers of the environment with some share of rule-making powers and coverage in these realms. While considerable deregulation has occurred in relation to the sectoral aspects of this regime, rule making has expanded in relation to the horizontal aspects of the regime and there is pressure for yet more rule making there. For example, energy–environment regulation of oil and gas in the North and on Canada’s frontiers is now influenced by laws such as the Oceans Act, which covers all three of Canada’s oceans. Centred in the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), this legislation extends the authority of DFO but also is supposed to engage other northern regulators, such as INAC. Such legislation prescribes such concepts as sustainable development, the precautionary approach and the ecosystem approach, along with the need for integrated management plans. There are also newer connections between energy and Chapter 4 107 rules regarding endangered species. So there is little doubt that the environmental and sustainable development aspects of the regime are growing in scope, with regulators expected to bring a greater range of concepts to bear on energy development. Climate change is by far the most challenging of these concepts, as I discuss later in this chapter. The environment aspects of the regime can also be seen as simply a system of rules and processes for ensuring the quality of energy products and services in an essential service industry, or in an industry with essential service elements. Environmental quality can relate to any number of risks and third-party effects regarding an energy product or service, such as leaded gasoline or new fuel additives; the safety of oil and gas pipelines; environmental assessments of new production plants or coal mines; and sustainable development involving reduced use of hydro-carbon and GHG-emitting fuels. The role of firms and consumers in this horizontal aspect of the regime involves a different set of dynamics. Firms face an array of federal and provincial environmental and quality regulators. Thus industry concerns, some tactical and some principled, centre on issues such as multiple requirements for hearings, long time periods to obtain approval for the use of products, and other logistical complexities related to dealing with multiple regulatory bodies. The role of industry and consumers in horizontal issues is a central element of my analysis of environmental assessment later in this chapter. The potential consumer-citizen split becomes even sharper in the environmental realm because when consuming an essential service product, individual Canadians may think and behave as citizens as much as consumers. In short, many consumer-citizens are aware of their desire to preserve and use energy in an environmentally friendly and sustainable way. Of course, they do not behave with total consistency on these matters, but there is little doubt that many such 108 See G. Bruce Doern and Monica Gattinger, Power Switch: Energy Regulatory Governance in the 21st Century (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003), Chapter 2. See also Michael Wenig, “Federal Policy and Alberta’s Oil and Gas: The Challenge of Biodiversity Conservation,” in Bruce Doern, ed., How Ottawa Spends 2004–2005: Mandate Change in the Paul Martin Era (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004), pp. 222–244. Red Tape, Red Flags consumer-citizens are interested both in what energy they consume and use, and in the quality of that consumption. Under increasingly globalized trade and free trade arrangements, as well as global environmental protocols, an international and continental set of actors, processes and rules also has to be factored in. They include bodies such as the International Energy Agency, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the NAFTA-centred Commission on Environmental Cooperation and other provisions of NAFTA. Context, Regime Change and Evolving Criticism Five key issues have set the context for energy–environment regulatory regime change and criticism over the last 20 years: energy industry views about the need for flexible, incentive-based economic and environmental regulation in a world where energy companies compete for investment and projects on a global basis; economic arguments about the need to internalize environmental costs in energy pricing; the impact of the sustainable development paradigm as a critique of both traditional energy and environmental regulation; the climate change debate, and Canada’s failed or non-existent regulatory strategy for dealing with it; and the role of alternative, renewable energy sources. Each of these issues is profiled briefly below. Energy Industries, Project Approvals and Incentive-Based Regulatory Flexibility Both the energy industry’s own assessments and those of independent analysts look at the regulatory regime in the context of national and global energy developments and forecasts, especially in the oil and gas sector. The core of the industry discussed in this section is involved with exploration, development, production and refining; oil Chapter 4 109 and gas pipeline transportation; and electricity generation, transmission and distribution. This core energy industry is clearly a crucial one for national economic development and for exports, especially to the United States. In Alberta, it is the anchor for the province’s current and future prosperity, centred on the massive oil sands development. Every industry forecast indicates that this core industry will need to continue to invest heavily in the coming decades to increase sources of supply and refinery capacity, and improve transportation. In this context, the energy industry’s future is strongly linked to energy– environment regulatory regime matters. As a recent Conference Board study stressed, three major challenges face the oil and gas industry: First, major energy investment projects are being delayed and have higher than expected costs because of skill shortages. The industry, like many others, faces the problem of an aging workforce, which will create a human resources challenge the industry will need to address within the next decade. Second, complex, time-consuming regulatory approval processes are also having an impact on major energy projects, whether they are oil and gas plants, pipelines, or electricity power generation or transmission. These processes are delaying projects that are needed to meet growing energy demands. Public resistance during the proposal and approval stages also hinders such new energy projects. Third, the energy industry must address major environmental issues. The expansion of oil sands projects is increasing industrial water use and could tax watersheds and affect Aboriginal communities. The projected growth in fossil fuel production and consumption will lead to a rise in air pollution and GHG emissions. All three of these challenges have regulatory regime links, but they are especially pivotal in relation to the second and third challenges. See The Conference Board of Canada, Mission Possible (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2007), Volume II, Chapter 5, and House of Commons, The Oil Sands: Toward Sustainable Development, Report of the Standing Committee on Natural Resources (Ottawa: House of Commons, March 2007). The Conference Board of Canada, Mission Possible, Volume II, p. 70. 110 Red Tape, Red Flags I will say more about that later in this section and in my discussion of the environmental assessment process. For at least the last decade, federal and provincial energy boards as regulators, under pressure from energy firms and associations, have generally tended to adopt more flexible and less “command and control” approaches to regulation. These approaches include alternative dispute resolution and, more recently, “goal-oriented regulation” as an alternative to so-called prescriptive regulation. This trend has been true of the federal National Energy Board and other key regulators, such as the Alberta Energy Utilities Board—not to mention the main U.S. energy regulator, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), whose approaches have had major impacts on Canada’s regulatory system. Overall, market-led approaches have been clearly in the ascendant over the regulatory approaches that prevailed before the 1980s. Much of this evolution made overall sense and helped generate considerable energy and economic prosperity. In the context of climate change pressures, the industry has favoured voluntary approaches and emissions intensity–based systems of regulation rather than absolute mandated reductions. As the main petroleumproducing province, Alberta in particular has practised this approach within the province and advocated it nationally. Alastair Lucas has concluded that Alberta has adopted this voluntary sectoral agreement approach to addressing provincial GHG emissions, particularly energy sector emissions, for three reasons: First, the emission reductions required are relatively undemanding. The provincial GHG emission target is expressed in terms of emissions intensity—GHG emissions relative to GDP—not absolute reduction. This, it becomes clear in the review of the Alberta Plan below, is not likely to reduce emissions, but merely to reduce the rate of increase in a rapidly growing provincial See National Energy Board, Goal-Oriented Regulation: Successes and Challenges in Partnering, presentation to the Community of Federal Regulators (Ottawa: November 7, 2006). Chapter 4 111 economy. A second reason is that volun­tary compliance in the energy sector is not new, but is reflected in the long-standing government–industry collaboration in regulation of air emissions and generally in the economic, social and environmental management of energy resource development in Alberta. The third reason is that Alberta’s proposed sectoral agreements are not purely voluntary. There is an explicit regulatory backstop, thus ensuring a firm legal basis for enforcement should voluntary arrangements fail in particular cases. From this perspective, the voluntary sectoral agreements are a valuable adjunct to legal requirements. There have, of course, been criticisms by environmental NGOs and others regarding the extent to which such approaches should be permitted or should dominate. Approaches do vary considerably among the provinces, both on core energy regulation and on the environmental side of the regulatory equation. A final but important aspect of energy-environment regulation centres on the degree to which an innovation agenda informs regulatory change. We have seen that such concerns have been crucial in the two previous case study chapters. However, in energy and the overall natural resources sector, the innovation dimensions are often somewhat more subliminal, although important nonetheless. The traditional energy sectors of oil and gas are often lumped in with natural resources as part of the “old” economy, rather than as part of the new knowledge-based and innovation-centred economy centred on telecommunication and biotechnology. Federal departments such as Natural Resources Canada have tried to counteract this “old” versus “new” economy perception. It has been right to do so, because although traditional energy companies do less R&D than many other sectors of 112 Alastair Lucas, “The Alberta Energy Sector’s Voluntary Approach to Climate Change: Context, Prospects and Limits,” in G. Bruce Doern, ed., Canadian Energy Policy and the Struggle for Sustainable Development (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), p. 293. Red Tape, Red Flags the economy, they are, nonetheless, strong and continuous adapters and users of new technology in their core exploration, production and transportation segments, especially regarding innovation in production processes and plant modernization. Key federal and provincial government R&D is also targeted at energy development, including oil sands development. These kinds of innovation-based activity are closely tied to the overall regulatory regime and its efficiency, approval times and efficacy in a world where decisions about where to invest and locate the next plant are increasingly global and fast. The innovation aspects of the energy–environment regulatory regime are also tied to each of the four analytical items that follow in this section: the internalization of environmental costs in energy prices, sustainable development, climate change and alternative energy. The Internalization of Environmental Costs in Energy Prices The energy aspects of the regime deal with several energy challenges, both in a global context and in respect of Canadian energy systems functioning within national, provincial and North American milieus. These energy challenges for energy regulators and policy-makers include the following: future prices, demand and supply for oil and other fuel and energy sources; broadening notions of energy security; natural gas, including liquefied natural gas, as a global energy source; climate change, the Kyoto Protocol and efforts beyond Kyoto; electricity and industry restructuring; alternative energy sources; and nuclear energy. All of these have environmental and sustainable development aspects that are increasingly inextricably linked. In one sense, there is consensus among energy economists, many environmental economists and some national energy policy-makers about what the optimum energy system for a country ought to be in the For discussion, see G. Bruce Doern and Jeffrey Kinder, Strategic Science in the Public Interest: Canada’s Government Laboratories and Science-Based Agencies (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007), Chapter 4. For discussion, see G. Bruce Doern, ed., Canadian Energy Policy and the Struggle for Sustainable Development (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005). Chapter 4 113 first decade of the 21st century.10 Ideally, all energy sources and supplies should be fully costed, with environmental costs internalized in market prices. Then, under a market system but with vigilant regulators, all sources should be allowed to compete on a level playing field, with incumbent suppliers having no contrived forms of protection and new entrants allowed entry into markets. In principle, oil, gas, coal, nuclear, hydro and alternative energy— such as wind power, solar power, and biomass—would compete openly and fairly. This approach would not only mean that alternative energy suppliers would not be encumbered by established green energy suppliers, but also that particular forms of alternative energy would not have unfair incumbent status over other forms of alternative energy. Each form of energy would, of course, have inherent technical and physical advantages and disadvantages as an energy source. And the demand side of the energy equation would be anchored in normal market behaviour, with no concentrations of buying power and with open and fair market prices, as well as good information about energy product quality. Overall, the energy–environment regulatory regime would regulate any monopolistic aspects and leave competitive forces to operate where energy truly functioned like any other market good. It would also regulate the industry through good environmental regulation, and good and open competition law and trade law. There would be a clear recognition that energy regulation has to govern an essential, networked service industry upon which industries and individual Canadians depend.11 While many of these aspirations for a good energy–environment regime garner considerable policy and institutional support, the realworld regime in Canada and elsewhere has not yet reached this state of affairs and might well never do so. Not surprisingly, the gap between ideal and real-life energy systems is due not only to the imperfections of markets but also to conflicting interests and fundamental political 10 See Dieter Helm, Energy, the State and the Market: British Energy Policy Since 1979 (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2003), and Dieter Helm, ed., Climate Change Policy (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2005). 11 See Doern and Gattinger, Power Switch. 114 Red Tape, Red Flags power relations, in a context where governments, their regulatory agencies, companies, and individuals as citizens and consumers compete, cooperate and collide in complex ways. Sustainable Development as a Policy–Regulatory Paradigm Criticism by advocates of the sustainable development paradigm has influenced the energy–environment regulatory regime. As mentioned earlier, sustainable development policies are designed to ensure, in any number of areas of governance, that the environment is left in at least as good a state for the next generation as it was for the current generation.12 Cast somewhat more loosely, governments often see such policies as those that consider economic, social and environmental effects—the so-called “triple bottom line.”13 In more specific energy policy terms, sustainable development progress is assessed using measures of energy efficiency—for instance, whether countries such as Canada have reduced per-capita energy use over the past 20 years. In Canada, such per capita usage has increased marginally, or improved only sluggishly in certain sectors but not others, so there is clearly much more to do. When the Kyoto Protocol and its requirements for reducing GHG emissions are added as a core test of sustainable development, then the Canadian record, as discussed later in this chapter, is still dubious in basic energy terms. Sustainable development as a policy goal has been endorsed by the federal government and is part of the statutory mandate of Natural Resources Canada, but it is not typically part of the statutory mandate of federal or provincial energy regulators. The federal government has pursued various rolling three-year strategies for sustainable development. They have been 12 See William M. Lafferty and James Meadowcroft, eds., Implementing Sustainable Development (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2000), and Francois Bregha, “The Federal Sustainable Development Strategy Process: Why Incrementalism Is not Enough,” in Bruce Doern, ed., Innovation, Science and Environment: Canadian Policies and Performance, 2006–2007 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006), pp. 82–104. 13Glen Toner, “Canada: From Early Frontrunner to Plodding Anchorman,” in William M. Lafferty and James Meadowcroft, eds., Implementing Sustainable Development (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2000), Chapter 3. Chapter 4 115 exhortative in nature, with federal departments producing targets and commitments. However, the follow-up on these promises has been criticized as being very inadequate. Moreover, the strategies are very decentralized at the departmental level. They are not complemented or guided by a government-wide federal strategy, much less an actual agenda.14 Despite the weakness of sustainable development strategies and their uncertain links to any actual regulation, let alone to preventive regulation, there is little doubt that the sustainable development paradigm will increasingly influence the energy–environment regulatory regime, in relation to both parent statutes and delegated rule making. In this context, regulatory tensions and challenges are bound to grow.15 The Climate Change Debate and Policy–Regulatory Failure The climate change debate and Canada’s failure to meet its international commitments under the Kyoto Protocol regarding GHG emission reductions are very large issues for the energy–environment regulatory regime. Space does not allow a full assessment in this section, but it is important to see how the evolving debate has coloured the regime and its larger politics and economics, including national unity issues. In the last decade, climate change policy, with a focus on the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, has been the centrepiece of the core interactions between energy policy and regulation on one hand, and environmental and sustainable development policy and regulation on the other. In 2007 some action seemed much more likely, although still of a very uncertain kind. This uncertainty was due both to national politics, where the Conservatives had to make policy as a minority government and reverse their pre-election position in the process, and global climate change politics. Comparative analyses show the wide variety of commitments Kyoto signatory countries made to reducing their GHG emissions by taking domestic measures or by arranging credits for reductions achieved in 14 Bregha, “The Federal Sustainable Development Strategy Process.” 15 See The Conference Board of Canada, Sustainability and Energy Security: Wrestling with Competing Futures, briefing (Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, April 2006). 116 Red Tape, Red Flags other countries.16 Canada undertook to reduce its GHG emissions by 6 per cent below its 1990 levels, averaged over the 2008 to 2012 period. But due to a huge lag in action, that commitment now requires us to cut emissions by over 30 per cent and hence represents an embarrassing failure by Canada to meet its international commitments. The federal Liberal government of Jean Chrétien only made the crucial decision to ratify the Kyoto Protocol in September 2002, a process completed late in 2002. In real terms the practical economic and technological decisions are only now being seriously and publicly debated, though they have been discussed semi-privately in policy-making circles for several years.17 The core problem is how to achieve the reduction targets, which Canada set without reference to the cost of meeting them or any clear sense of the mixture of regulation and technology to be used to do so. The global context of Kyoto since the early 1990s has been forged around the refusal of the U.S. to sign the protocol and to opt instead, during the George W. Bush presidency, for a technology-first approach rather than any regulatory, interventionist approach. In February 2002, the Bush Administration announced its own unilateral alternative to Kyoto, centred on voluntary approaches for U.S. energy producers and incentives for developing new alternative energy technologies. The politics of the Kyoto Protocol also centred on the fact that developing countries were not part of the protocol, on the grounds that the developed western countries had essentially created the problem and that developing countries would need more energy as they grew and, hopefully, prospered economically. Increasingly, particularly following the 2005 Gleneagles G8 summit, the Bush Administration—backed by big U.S. energy interests—began forging a small, alternative, “beyond Kyoto” coalition of countries around the Asia-Pacific Partnership on 16 See Mark Jaccard, Sustainable Fossil Fuels (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2006). 17Debora VanNijnatten and Douglas MacDonald, “Reconciling Energy and Climate Change Policies: How Ottawa Blends,” in G. Bruce Doern, ed., How Ottawa Spends 2003–2004: Regime Change and Policy Shift (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 72–88. Chapter 4 117 Clean Development and Climate. It consisted of Kyoto non-signatory countries that, crucially, included China and India, the two dynamic developing economies with insatiable energy needs whose fast-growing GHG emissions could also negate climate change progress in other ways. Indeed, key advocates of the Kyoto Protocol saw the protocol, even if implemented successfully, as merely the first in a series of steps that would be needed to tackle climate change in the decades beyond the protocol’s end date of 2012. As Canadian analysts have shown, Canada’s underperformance was largely due to policy and regulatory failures. However, it was also due to Canada’s greater population growth and economic growth relative to many other countries during the last decade.18 Canada’s strategies were proceeding in tandem with international developments through new domestic institutional processes. After the 1997 Kyoto Protocol was negotiated, Prime Minister Chrétien and the first ministers directed the federal, provincial and territorial ministers of energy and environment to examine the impacts, costs and benefits of implementing the Kyoto Protocol, as well as the options for addressing climate change. However, they were to do so under a guiding principle that no region should bear an unreasonable burden due to implementing the Kyoto Protocol. Thus was implanted, at the political level, the central importance of equity considerations among Canada’s regions, analogous to the larger equity debate in the global negotiations among countries. Such a guideline was undoubtedly needed in an overall national unity sense, particularly to accommodate Alberta. Alberta was already often rhetorically casting federal policy on Kyoto as “another National Energy Program,” a reference to the highly interventionist 1980 Liberal policy that Albertans detested. Of course, Alberta knew that it was the province at the heart of the carbon-producing part, albeit not the core carbon-using part, of the Canadian economy. Central Canadian 18Nic Rivers and Mark Jaccard, “Talking Without Walking: Canada’s Ineffective Climate Effort,” in Burkard Eberlein and G. Bruce Doern, eds., Governing the Energy Challenge: Germany and Canada in a Multi-Level Regional and Global Context (manuscript under review), Chapter 11. 118 Red Tape, Red Flags industries were also major carbon emitters and, of course, Canadian consumers were also energy “polluters” in a fundamental sense. The current Conservative government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper has its power base in Alberta, Canada’s oil and oil sands heartland, and it has spoken openly about alternatives to Kyoto in two ways.19 First, the government has argued that Canada’s current Kyoto policy is based too much on using foreign credits rather than on actually taking action in Canada. Accordingly, it initially called for a “made in Canada” policy that would take action on energy and clean air, and that would foster more voluntary approaches in close consultation with the provinces and industry. It also cancelled several previous Liberal government Kyoto funding initiatives, later crafting some alternatives. Secondly, the government has joined the Bush “second front” coalition, which favours a technology-first approach. An anti-Kyoto and beyond-Kyoto position is also inherent in Prime Minister Harper’s declaration that he believes Canada is, and will remain under his government’s pro-energy policies, a global “energy superpower.” The federal government also had to backtrack quickly. In April 2007, it presented its somewhat regulation-centred climate change strategy. The strategy committed Canada to a 20-per-cent reduction in emissions below 2006 levels by 2020.20 That is a far cry from the much deeper Kyoto commitments, which the federal Conservative government argued would seriously harm the Canadian economy, especially given its trade dependence on the U.S. market where U.S. competitors did not have to deal with a Kyoto regulatory burden. These dynamics, however, are not the only ones at play in Canada. Several provinces are strongly pro-Kyoto, as are the three main federal opposition parties. Quebec has announced that it will introduce a carbon tax. City governments have also announced a pro-Kyoto alliance. 19 See Peter Calamai, “The Struggle Over Canada’s Role in the Post-Kyoto World,” in G. Bruce Doern, ed., Innovation, Science, Environment: Canadian Policies and Performance 2007–2008 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), pp. 32–54. 20Environment Canada, Turning the Corner: An Action Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gases and Air Pollution (Ottawa: Environment Canada, April 2007). Chapter 4 119 Regardless of these developments—some very rapid and some not well planned—climate change issues will colour the overall political economy of the energy–environment regulatory regime. Alternative Renewable Energy Sources and Regulatory Push The final but still crucial aspect of regime context, change and criticism centres on the place—or lack thereof—in the energy–environment regulatory regime of alternative renewable energy sources. It also poses challenges for environmental assessment, to be discussed in the next section of this chapter. Alternative energy sources are the preferred energy option of most environmental lobby groups, which strongly oppose current energy policies focused on coal, oil, natural gas and nuclear energy. Such alternatives include low-impact renewables, such as some biofuels, wind, solar, biomass and small hydro (with big hydro often excluded as a “renewable” because of its major adverse environmental impacts in creating huge hydro dams). Advocates believe policies and rule making on alternative energy will meet multiple key objectives, including sustainable development, climate change reduction and protection, air quality enhancement and—because of the decentralized nature of alternative energy sources—energy security. Because they involve new technologies, these energy sources are also often advanced as part of national industrial and innovation policies.21 The general public’s views of alternative energy sources are mixed. Wind power is supported, but often only as long as proposed wind turbines are not in one’s proverbial “backyard” as environmental eyesores. Some people see renewables in a vague, overall way as small, popular and pricey. 21 International Energy Agency, Energy Technology Perspectives: Scenarios and Strategies to 2050 (Paris: International Energy Agency, 2006). 120 Red Tape, Red Flags Policies regarding renewables are mixtures of price subsidies, frontend innovation and R&D incentives, and regulatory targets for the proportion of energy supplied by such sources. Clearly, the extent to which such renewables are fostered in different countries depends on the power and influence of incumbent energy suppliers and providers relative to that of new supplier industries, in combination with environmental groups and lobbies, and regional and national political and public opinion (especially in a federation). Municipal pressure can also be at play here, especially when municipalities own and operate local electrical utilities. But despite considerable lobbying and some governmental support, renewable energy is still seen as a small (but growing) share of world energy supply. International Energy Agency forecasts see it tripling by 2030 but still only occupying 6 per cent of use globally. Germany is pre-eminent in the promotion of renewable energy sources for electricity generation.22 By 2005, Germany had installed wind power capacity of 18,427.5MW and photovoltaic capacity of 1,537MW, compared with Canada’s 683MW for wind and 14.9MW for photovoltaics. In Canada, alternative energy has been barely visible in terms of overall energy regulatory and policy practice. That is partly due to strong provincial governmental control over electricity policy and partly to the fact that there is scarcely any east–west electricity grid, which would give the federal government some policy leverage. But even if there had been pan-Canadian control and infrastructure, it is unlikely that federal initiatives would have emerged. Federal policies, as we have seen, have focused on oil, gas and nuclear power. For most of the 1980s and 1990s, they were based on strong support for liberalized markets, a view that did not extend to the necessary task of creating markets for alternative energy through “regulatory push.” In the early years of the 21st century, some initiatives 22Danyel Reiche, Handbook of Renewable Energies in the European Union: Case-Studies of the EU-15 States, 2nd ed. (Bern, Switzerland: Verlag Peter Lang, 2005). See also Herman Scheer, Energy Autonomy: The Economic, Social and Technological Case for Renewable Energy (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007). Chapter 4 121 for so-called green power began to emerge in some provinces, such as Ontario, Quebec and Prince Edward Island.23 These are likely to grow and to receive various kinds of increased technology and innovation funding. However, overall, the place of alternative energy in Canada has been very marginal in the face of interests and governments whose priorities have been elsewhere. As mentioned earlier, even Canada’s hydro power sources are rarely seen as truly renewable. In Quebec, Aboriginal groups are still engaged in lawsuits against Hydro-Québec and the Quebec provincial government for the damage caused by the earlier building of huge hydroelectric dams. Only small hydro, which is less disruptive of the environment, fits the current definitional bill of renewable energy. Illustrative Regime Change: Environmental Assessment and Energy Projects My more detailed illustrative example of regime change and inertia centres on the dynamics involved in regulation through environmental assessments of energy projects. As noted earlier, this process involves an array of regulators at several levels of government. (See text box entitled, “Core Energy–Environment Regulatory Regime Project and Related Processes.”) The mandate of the main federal agency, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA), is to “provide Canadians with high quality environmental assessments that contribute to informed decision making in support of sustainable development.”24 The president of the CEAA reports directly to the minister of the environment and functions under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, the Canada-Wide Accord 23 Judith Lipp, “Renewable Energy Policies and the Provinces,” in G. Bruce Doern, ed., Innovation, Science, Environment: Canadian Policies and Performance 2007–2008 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), pp. 176–199. 24 Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, Report on Plans and Priorities 2006–2007 (Ottawa: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, 2007), p. 3. 122 Red Tape, Red Flags on Environmental Harmonization, bilateral agreements with provincial governments, and international agreements, including the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context. The Environmental Assessment Act was amended in 2003 to consolidate the way federal environmental assessments are conducted. In 2004, the federal External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation made further recommendations about environmental assessment (as discussed later in this chapter).25 The principle of self-assessment is the basis of the federal environmental assessment regime. Thus, federal departments and agencies conduct their own assessments in their mandate areas, drawing on their expertise. Often, several departments can be involved in assessing the same project. Departments and agencies must conduct assessments before they carry out a project if they: provide financial assistance to enable a project to be carried out; sell, lease or otherwise transfer control or administration of land to enable a project to be undertaken; or issue authorizations to enable a project to go forward. The volume of assessments ranges between 6,000 and 7,000 annually, and since the Act came into effect in 1995, more than 50,000 projects have been assessed.26 There is no publicly available breakdown of these projects by sector, although energy projects are bound to comprise a reasonably significant percentage of the total. Environmental assessment is seen broadly as a project planning tool used to help eliminate or reduce potential harm to the environment resulting from the above-noted forms of federal involvement. Federal legislation provides for four types of environmental assessment: screening, comprehensive study, mediation and assessment by a review panel; but most projects are assessed through quite minimal screenings. The Comprehensive Study List Regulations under the Act identify those projects likely to result in significant environmental effects, 25 See External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, Smart Regulation: A Regulatory Strategy for Canada (Ottawa: External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, 2004), pp. 100–111. 26 Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, Report on Plans and Priorities 2006–2007, p. 9. Chapter 4 123 which thus require a comprehensive study assessment. Screenings can take several months, whereas comprehensive studies require about a year and review panels can take over a year.27 The 2003 amendments to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act resulted in several changes in response to a decade or more of criticism. These changes included: the creation of a federal environmental assessment coordinator role; a mandate to establish a quality assurance program to examine federal assessments; a requirement to create an Internet database of all federal environmental assessments; mandatory follow-up programs for specified projects; tools to deal efficiently with projects that have inconsequential effects; a more certain comprehensive study process; more opportunities for public participation in the comprehensive study process, supported by participant funding; and the use of regional environmental studies.28 In 2005, the follow-up Cabinet Directive on Implementation of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act took effect. Its purpose is to ensure that the administration of the Act results “in a timely and predictable environmental assessment process that produces high quality environmental assessments.”29 This directive was an interim measure until other legislative amendments to achieve consolidation took effect. Thus, though efficiency and timeliness were the overriding goals, the directive also had to specify that it did not fetter the powers, duties, functions or discretion of federal authorities. 27External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, Smart Regulation, p. 100. 28 Ibid., p. 101. 29 Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, Cabinet Directive on Implementing the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (Ottawa: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, November 2005), www.ceaa.gc.ca/013/010/directives_e.htm 124 Red Tape, Red Flags In Budget 2007, the current Conservative government announced that it was creating a Major Projects Management Office to streamline the review of large natural resource projects. With an investment of $60 million over two years, “the Government seeks to cut in half the average regulatory review period from four years to about two years, without compromising our regulatory standards.”30 This kind of red-tape and red-flags commitment regarding projects raises a key issue about environmental assessment as it affects energy. Energy is but one sector subject to environmental assessment processes, so such processes are not designed with only energy in mind. Even the Major Projects Management Office is designed for “natural resource projects,” which will cover mining, minerals and forestry projects as well as energy projects. In addition, major projects will have to be differentiated from minor or smaller ones in some way. Nonetheless, there is evidence that the CEAA is more sensitized to energy issues, since it notes in its Report on Plans and Priorities 2006–2007 that an “increase in demand for energy is likely to result in more energy-related development projects” and that “environmental assessment is a useful tool for ensuring that the Government’s climate change policies are considered in project development and that projects take into consideration the potential effects of changes in climate.”31 The mapping of the environmental assessment system has thus far only referred to its federal government aspects. The provinces and territories also have policies and regulations regarding environmental assessment. Space does not allow a full account of these 13 further systems, but key features need to be noted. First, most provinces carry out their environmental assessments through one agency rather than using the federal government’s selfassessment process for its departments and agencies. Second, there are inevitable areas of split and overlapping jurisdiction. Canadian federalism’s constitutional division of powers was devised well before 30Department of Finance, Budget 2007: Aspire to a Stronger, Safer, Better Canada (Ottawa: Department of Finance, 2007), Chapter 5, p. 2. 31 Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, Report on Plans and Priorities 2006–2007, p. 12. Chapter 4 125 governments even had environmental policies. The split jurisdiction nonetheless found its way into de facto practice in areas of natural resource development largely because of provincial ownership of natural resources. But even in this sphere, there are areas of federal jurisdiction for projects that cross interprovincial and international boundaries and for projects that affect fish habitat and navigable waters. Coordination problems regarding this kind of multi-level regulation have been the subject of complaints for many years. One initial response to complaints about multiple assessments of the same project, serious time delays and different assessment criteria was the establishment of the Sub-Agreement on Environmental Assessment under the previously mentioned Canada-Wide Accord on Environmental Harmonization. The purpose of this sub-agreement is to “promote the effective application of environmental assessment when two or more governments are required by their respective laws to assess the same proposed project. It includes provisions for shared principles, common information elements, a defined series of assessment stages and a single assessment and public hearing process.”32 Some progress has occurred under these coordination mechanisms, such as the joint review of some oil sands projects by the federal government and the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board. However, when the External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation reviewed environmental assessment in 2004, it heard in no uncertain terms from industry and from NGOs about serious problems regarding timing, information requirements and public participation.33 The smart regulation study’s review of federal and provincial environmental assessment regulation did not focus specifically on energy projects. However, much of its overall commentary and assessment of this system, and of the larger energy–environment regulatory regime of which it is a part, is important to note. The study stressed that “the environmental assessment process is one of the issues about which the Committee heard the most complaints and 32External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, Smart Regulation, p. 103. 33 Ibid., pp. 102–104. 126 Red Tape, Red Flags it was viewed as a key priority for regulatory reform by many industry and environmental non-governmental organizations. . . . It also heard skepticism over whether the [then] recent changes to the CEAA would make the environmental process much more effective or, in some cases, even more cumbersome.”34 The smart regulation study concluded that the remaining problems were such that a new approach was needed that moved “beyond harmonization and towards a single, nationally integrated approach encompassing federal, provincial and territorial processes” and that such an idea “was generally supported by both industry representatives and non-governmental organizations during our consultations.”35 If such reforms were not carried out, the smart regulation committee argued, the “credibility of the assessment process will continue to erode and its effective use will be jeopardized.” Moreover, the committee said, such reforms would help governments conduct “a more holistic assessment of a project and [enable] the development of expertise in this area. . . . and also improve the consideration of cumulative impacts of several projects on a single eco-system and ensure that the environmental assessment process adapts to new scientific advances and changing circumstances.”36 Clearly, such reforms would require almost unprecedented levels of cooperation and coordination within the federal government, and among the federal government, the provinces and the territories. They would also require statutory change and regulatory–legal change, not to mention significant resource commitments. At time of writing, there is clearly some level of recognition of the problems at hand. The CEAA’s three stated priorities under the Conservative government are as follows: “build a framework for a more integrated environmental assessment, assume a more active leadership 34 Ibid., p. 101. 35 Ibid., p. 104. 36 Ibid., pp. 104–105. Chapter 4 127 role in federal environmental assessment and build the capacity to deliver on existing and new responsibilities.”37 In addition, there is the newly announced Major Projects Management Office for natural resource projects, whose links to the CEAA process are still highly ambiguous, in terms of both regulatory law and practice. Conclusion The energy–environment regulatory regime presents a regulatory realm that in some respects is quite different from those explored in the two previous chapters but in other respects is very similar. The differences begin with the relatively greater focus in the energy–environment regulatory regime on projects rather than products, and with the growing need to deal with different spatial and ecosystem aspects of energy– environment interactions. The similarities centre on the need by complex sets of federal, provincial, local and international regulators to deal with the speed and complexity of energy investment and location choices. These choices are crucial for an ever more globally focused industry but also for an essential networked service industry, some aspects of which are unambiguously market centred and other parts of which are very much managed markets. In this regime, the issue of consumer and citizen demands for faster, wider access to new products does not seem as obvious as it was in the sectors analyzed in previous chapters, in part because projects rather than products seem to be the dominant initial focus. However, projects are intricately tied to providing fast access to badly needed energy products, sources and services. In addition, faster access to the right mix of energy products, services, sources and production processes is central to the politics and economics of the climate change aspects of energy–environment regulation. For instance, environmental NGOs 37 Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, Report on Plans and Priorities 2006–2007, p. 5. 128 Red Tape, Red Flags and consumer-citizens interested in the sustainable quality of the energy they use, rather than just its price, exert pressure to introduce or factor in more alternative energy sources and products through regulatory push. The complex nature of science-based regulation also does not initially seem to have as strong a connection to this case study as to our two previous case studies, in part because energy is too often easily cast as part of the old resource economy rather than the science- and innovation-based knowledge economy. This view, however, is far too simplistic, in that environmental science is crucial to understanding the issues to be addressed. Scientific evaluation of new technologies is also required to ensure they are environmentally superior. Thus, this core force for change is very much a central driver of the energy–environment regulatory regime as well. That is true in many of the ways in which regime evolution has been discussed in this chapter. First, new energy projects subject to environmental assessment are imbued with decisions and views about which new production technologies and processes are best suited to meeting environmental and sustainable development goals and requirements. The more that sustainable development values are added to the equation, the more S&T and innovative ideas emerge as a necessary corollary. Climate change issues also go to the heart of the way technology-forcing strategies become part of regulatory regime strategy. Discussions of alternative energy sources also focus strongly on the role and availability of new and improved technologies. The earlier discussion of the particular dynamics of regulating environmental assessments via the CEAA and federal departments highlighted continuing red-tape and red-flag dilemmas and choices. For at least the last decade, industry has protested about the slowness and rigidity of the federal assessment regime and of federal–provincial coordination. Environmental NGOs still focus on red-flag issues, but to a much greater extent than in the past, they too see the need for speed. That may be increasingly the case as NGOs press for new renewable energy sources whose environmental politics may produce considerable local opposition of the “okay in principle but not in my backyard” variety. Chapter 4 129 Regarding the agenda-setting argument and the need for related institutional reform, the energy–environment regulatory regime is a good example of the need for more strategic approaches to linked areas of rule making. The slowness of project approval reforms is evident. The climate change aspect of regime development is a national embarrassment, and alternative renewable energy development lags seriously behind that in other countries. There has been no serious mechanism for fully and seriously debating these issues, either in Canada’s regulatory system or in other policy realms. 130 Red Tape, Red Flags 5 Federal Regulatory Policy: An Annual Regulatory Agenda and Related Institutional Reform T he previous chapters have shown, in three case studies, the degree to which the real regulatory world is increasingly composed of intricate regulatory regimes rather than single regulators or simple processes. This kind of complex rule making is no longer the exception but, rather, is the norm. Regulation in the innovation age requires reform that goes beyond periodic reform exercises and beyond current federal regulatory policy statements, which are still largely centred on a one-regulation-at-a-time approach and on the stages that proposed new regulations go through. The process of dealing with both red-tape and red-flag issues and with the set of forces and pressures examined in Chapter 1 requires an actual regulatory agenda and related institutional reform as a needed chapeau for regulatory governance in Canada. Because most rule making involves multiple departments and agencies within the federal government—and among federal, provincial and foreign governments—an agenda process is needed to focus on the most crucial areas of regulation and to improve coordination, eliminate duplication and maximize the benefits of regulation. Such a process also needs arm’s-length institutional expertise and advice provided regularly through a Regulatory and Risk Review Commission, rather than just once a decade through periodic regulatory reform exercises. In this chapter, I look at several features related to establishing a fully functioning federal regulatory agenda and agenda-setting process, and a new Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. The suggested agenda-setting process would set annual priorities for new regulation more transparently than current processes do, through a Cabinet-led process that could better handle some of the regime-level coordination problems and other issues explored in this study. The Regulatory and Risk Review Commission would be an arm’s-length expert body that would monitor and report on regulatory trends and cross-governmental risk profiles. While this chapter focuses on a federal regulatory agenda, similar arguments can be mounted for each province to have an overall regulatory agenda as well. Regulation in Canada is increasingly multi-level, Chapter 5 133 and regulatory regimes clearly involve both federal and provincial governments, not to mention foreign and municipal rule-makers. The Province of British Columbia has an overall regulatory strategy that in some ways comes close to what I am suggesting in this study. It is a premier-led initiative that has focused on reducing red tape and significantly eliminating rules, and it has annual reporting requirements. (See the commentary by the lead B.C. minister at the end of this volume.) It is not a complete agenda as suggested in this chapter, in that it does not annually reveal provincial priorities for new regulations in different policy fields. However, the fact that it is a premier-led initiative is extremely important as a model for efforts that other jurisdictions might make. Chapter 1 has provided an initial look at the way the current federal regulatory system functions, but we now need to go well beyond this account to see what a regulatory agenda process would involve. To do so, this chapter proceeds in four sections. The first section looks at what is wrong with the current federal approach to regulation and makes the basic case for a regulatory agenda based on the previously discussed three forces of political, economic and democratic change, the growing need to manage complex regulatory regimes, and the broader need for democratic and more transparent agenda setting to complement processes that already exist for taxation and spending. The second section examines a key logical question: namely, “To what extent does regulatory agenda setting occur now?” The third section examines what a more complete regulatory agenda and agenda-setting process would look like and what they would consist of. The fourth section examines the need for a complementary, arm’s-length expert advisory Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. Conclusions follow. 134 Red Tape, Red Flags What Is Wrong With the Current Approach to Regulation? The Basic Case for an Annual Regulatory Agenda What is wrong with the current federal approach to regulation in relation to the growing importance of complex regulatory regimes, as discussed in the three case studies? Furthermore, if an annual regulatory agenda dealt only with new regulations, as suggested below, how would it help address the issues raised in previous chapters? The heart of the “what is wrong” question is that far too much of the current federal approach to regulation is premised on a one-regulationat-a-time approach. This approach essentially drives the official federal regulatory policy. Such an approach does not properly evaluate new regulations in relation to current ones across federal departments and agencies and in others levels of government. It fails to deal adequately with the interacting features of the regulatory environment, including a government-wide view of risk profiles and priorities, and thus falls short of meeting the requirements for regulation in the innovation age. As Chapter 1 showed, federal regulatory policy has evolved since 1986, when regulators were required to consult affected parties and the public, to conduct analysis and produce a regulatory impact analysis statement (RIAS), and to pre-publish the regulatory proposal. The policy was later expanded to include decision-making criteria, such as ensuring net benefits to Canadian society, minimizing regulatory burden, fostering intergovernmental coordination and cooperation, meeting regulatory process management standards and linking to Cabinet directives. Intergovernmental and interdepartmental coordination is mentioned in the policy, so some complex regulatory regime issues are acknowledged, but the policy does not include adequate, regular cross-governmental review and institutional support. Even the decision in the recent federal Directive on Streamlining Regulation to add a life-cycle approach to this policy, while highly desirable, still largely reflects a one-regulation-at-a-time approach. The Chapter 5 135 life-cycle approach will extend the policy past the regulation proposal and approval stages to include subsequent enforcement, compliance and evaluation stages. Can one even imagine the federal government managing its tax and spending system in the way it manages its regulatory system? Would a government have an overall tax policy or spending policy that simply said, “Each time a new tax decision or a new spending decision is contemplated, be sure to conduct a tax or spending impact assessment, consider alternatives to spending and taxation (such as regulation), use a life-cycle approach and consult with Canadians”? Such a system for taxation and spending is unthinkable, precisely because governments know that they must have an annual agenda for both these halves of the fiscal coin. Governments also assemble the required data to inform their tax and spending priority setting. This kind of agenda setting is not perfect, of course, but it is far more developed than its counterpart in the regulatory realm. In addition, it is seen to be a crucial responsibility of democratic government, all the more so in an interdependent international setting. What is wrong and inadequate about the current federal regulatory system is that—as discussed in more detail later in this chapter—the federal government has no obvious or transparent way to determine which areas of regulation are most important. Such a process would allow it to deal with priority areas in a considered, cross-governmental manner and then to implement new regulations, along with the necessary S&T underpinnings, and financial and staffing resources. The federal government does not even routinely present systematic information to Parliament or Canadians on the annual rate of growth (or contraction) of regulation. There are, to be sure, some issues regarding what kinds of further data are needed­—hence the suggestion to establish a Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. But regulatory agenda setting does not need to wait for perfect regulatory data. Historically, public spending and tax agenda setting proceeded without perfect data; later, agenda-setting needs triggered improvements in the ways governments acquired, analyzed, interpreted and debated data. The point is, however, that governments have simply been lax in making an 136 Red Tape, Red Flags equivalent effort regarding regulation. Such an effort is needed not only for normal democratic and accountability reasons, but also to support the kind of annual agenda setting suggested in this chapter. Regulation is at least a third of what governments do—but considered, transparent government-wide agendas do not openly inform it or anchor it. The difficulty with the current approach is that more and more regulation is complex. When proposing new rules and implementing current ones, multiple sets of regulators affect each other, as well as any number of firms, consumers and citizens. In short, multiple cycles, and multiple life cycles of rule making and enforcement, are increasingly the norm. For example, as we have seen, the full regulatory process for new drugs involves decisions on intellectual property (patents), clinical trials, drug review and approval, and approval for funding under medicare. The answer to the second question posed above—namely, “If an annual regulatory agenda dealt only with new regulations, as suggested below, how would it help address the issues raised in previous chapters?”—is closely linked. Such an agenda could help address complex regulatory regime problems because new regulations are almost inevitably linked to existing ones, and to past and future enforcement and compliance issues. If new regulations are reviewed and ranked in a more overt way than they are at present, and in relation to multi-agency regulatory cycles and science and risk profiles, then coordination issues are far more likely to be recognized and managed. It must be stressed that an annual regulatory agenda would not solve all coordination problems, any more than the annual tax and spending agendas fully solve tax and spending coordination problems. Some of these coordination problems undoubtedly require action at other middle and micro agency levels, or actions among agencies and stakeholders carried out through bodies like the theme tables mentioned in Chapter 1, which were established in the post-smart regulation reform period. Overall, however, government would be better able to respond to the three forces examined in Chapter 1 and revealed in more detail in the three regulatory regime case studies if it had an annual regulatory agenda. This agenda would address regulatory priorities in a strategic, integrated way Chapter 5 137 to better manage the complexity of regulation and to ensure that new regulations respond to economic and technological changes. This agenda would better balance, in a transparent way, the need to limit regulatory burden to ensure business competitiveness and the need to protect the environment and people. An annual agenda would also help better manage the challenges posed by growing consumer demand for faster access to new products and the desire for democratic regulatory processes. Finally, this agenda would better ensure that science-based and related risk analysis capacity is properly allocated to aid regulatory decisions, enforcement and compliance. The basic argument for an annual regulatory agenda reflects the interacting impacts of all three forces operating in the innovation age. However, it is also based on larger but closely related concerns about democratic agenda setting. The speed of economic and technological change, and demands to deal with both red-tape and red-flag concerns, mean that governments need to have a more concerted way to think about, set and act on regulatory priorities. In part, this call for a more explicit regulatory agenda is also an appeal for greater rationality in regulatory governance, to complement the greater sense of agenda setting that already exists regarding taxation and spending. Agenda setting for taxation and spending takes place partly via the annual budget process and partly via the SFT. The latter agenda-setting process occurs every 18 months or so, at the discretion of the prime minister. There is, of course, crucially present here an inherent democratic argument for more formal agenda setting that can be subject to scrutiny and criticism. The current federal government won power in 2006 by presenting a five-point agenda, precisely on the grounds that 138 For analyses of the rational, tactical and random nature of agenda setting, see Stuart N. Soroka, Agenda-Setting Dynamics in Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2001), and John Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd edition (Harper Collins, 1996). For a discussion of Canadian federal agenda setting or priority setting linked closely to prime ministerial leadership and preferences, see G. Bruce Doern and Richard Phidd, Canadian Public Policy: Ideas, Structure, Process, 2nd edition (Scarborough, Ontario: Nelson Canada, 1992), chapters 8 and 9. Red Tape, Red Flags government needed more focus so that Canadians could better understand what it believed were its key initial challenges. I return to this basic argument in the conclusion to this chapter; but first, more needs to be said about two logically linked questions and issues noted in the introduction to this chapter. First, does the federal government already have some kind of internal, informal annual regulatory agenda that is simply not very apparent to the rest of us? And second, what would a more complete and democratic annual regulatory agenda process look like, and how might it work? To What Extent Does Regulatory Agenda Setting Occur Now? We need to ask the first question because if such a system exists and is working well, why should the regulatory agenda argument being advanced here be carried any further? We therefore need to look at four elements that provide partial answers to this question: the agenda setting that goes on within departments that have major science-based regulatory tasks, and within other regulatory bodies; departmental reports on plans and priorities, which are submitted during the annual expenditure process; the SFT and related priorities regarding legislative bills that go before the House of Commons; and the recent launch of an experimental “triage” process, whereby departments are invited to identify high, medium and low priorities for regulation, which will then receive different levels of regulatory focus and resource support. Agenda setting within departments and individual regulatory bodies is something one is tempted to assume must “obviously” occur, somehow. Large regulatory departments, such as Health Canada, Environment Canada and Transport Canada—and major regulatory bodies, such as the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, the Therapeutic Products Directorate, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Chapter 5 139 Commission, and the National Energy Board—have to plan their activity regarding new regulations or major amendments. Senior officials within these organizations have to determine which regulatory changes should come first as they schedule their notices of proposed new regulations, their planned RIASs and other features of the overall federal policy on regulation. Research for this study suggests that some kind of agenda setting of this kind does occur at the departmental level, but it is not aggregated at the centre of government. Nor is it announced as a series of forthcoming or even implicitly ranked regulatory changes. And, of course, it is hard to know what regulatory proposals never see the light of day, having been screened out through discussion within the department or at ministerial levels. In the early 1990s, departments were required to publish annual regulatory plans, an experiment that lasted only a couple of years. It was scuttled when heavy budget cuts occurred in the battle against the then-huge federal deficit. Even these so-called plans were, in fact, just veritable “wish lists” of forthcoming new regulations. The recent federal Directive on Streamlining Regulation also indicates that departments must prepare regulatory plans, but there is no indication that an overall annual regulatory agenda will emerge from these disaggregated plans, or that it will deal with complex and changing regulatory regime issues. If informal departmental and agency planning of some kind exists, it is certainly not aggregated in any departmental documents—including the annual plans and priorities documents, which are discussed later in this chapter. And these departmental plans are not aggregated higher up at the central agency or Cabinet level, either. We might also glimpse agendas and planning in the annual plans and priorities documents that departments are required to submit as part of the annual expenditure process. These documents are supposed to aid On the related federal expenditure and tax processes, including their agenda-setting features and dynamics, see David Good, The Politics of Public Money (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007), and Geoffrey Hale, The Politics of Taxation (Guelph, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2001). 140 Red Tape, Red Flags parliamentary scrutiny, both at the level of the initial plans and during later parliamentary review of performance and results. The author’s reading of a sample of these departmental documents over the past few years reveals that regulatory items certainly may be mentioned in them. However, information on these items is cursory. Moreover, the priorities shown are an amalgam of spending and regulatory changes, with spending clearly given the dominant focus. There is little evidence of a regulatory agenda for each department and, again, there is no overall aggregation of these plans on a government-wide basis. The SFT and related legislative priority setting comprise another obvious and central part of the system. I stressed earlier that the SFT is not an annual process, but it clearly must be looked at regarding overall agenda setting. In the past, SFTs were mainly occasions to announce legislative priorities. Since such laws always contain rules in the body of the statute, they perforce reveal something about rule making, though not necessarily about delegated law. That comes later, after bills have become law. Over many years, however, SFTs have evolved to become major occasions when governments present their overall values and themes, along with some specific policy priorities, within which might well be some regulatory matters. To the extent that such regulatory matters get mentioned in an SFT, one is entitled to argue that they are somehow high priorities for the next SFT period, which lasts roughly 18 months. For example, the current Conservative government mentioned its Federal Accountability Act in its first SFT in 2006. The eventual parent law, the changes to many other laws and the new required regulations approved as delegated law were all unambiguously regulatory in nature. I will return later to the SFT’s role in revealing regulatory priorities. Suffice it to say at this point that it is a very imperfect occasion for such regulatory agenda setting. The last and most recent reform with possible agenda-setting implications is the experimental framework for the triage of regulatory submissions, a process currently underway between the Treasury Board Secretariat’s Regulatory Affairs Division and a few departments. Chapter 5 141 The External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation suggested the triage concept. The idea is that departments would ask themselves a series of questions early in the regulatory proposal stage. On the basis of the answers to these questions, they would separate their new rulemaking plans into high, medium and low priorities. These priorities would imply different levels of resources and, perhaps, different decisions about conducting RIASs, or different treatment if international obligations and regulation were involved. The triage experiment is a partial recognition that something more closely resembling a regulatory agenda is needed, at least at the departmental level. However, there is no mention here of a cross-governmental triage process. Thus, once again, there is a hint of the need for agenda setting but only quite weak or experimental follow-through in practical governance terms. These examples of partial, informal and unclear regulatory agendasetting processes and dynamics can certainly be built upon. However, they do not at present indicate that there is any full-blown or obvious agenda-setting process or arena for strategic regulation. Agenda setting is at best a hit-and-miss process, from the perspective of any outsider looking at how and why governments regulate in some areas but not in others each year. It is, without doubt, a far less explicit and transparent process than either the tax and expenditure agenda-setting processes or the overall SFT process. None of these latter processes is perfect, but they are each informed by the view that agenda setting is important and should be reasonably transparent. I will return to these issues after discussing what a more explicit regulatory agenda process might look like. A More Complete Regulatory Agenda and AgendaSetting Process: What Would They Look Like? A more complete, transparent and strategic regulatory agenda-setting process that debated, set and announced federal regulatory priorities would have several features. Some of them are similar to features of the tax and 142 Red Tape, Red Flags spending agenda-setting processes, and others are different because regulation itself is different. These features are: a process whereby all proposed new regulations from across federal departments and agencies would be aggregated annually and priorities determined at the Cabinet level; a determination of what would be included as proposed new regulations; a provision and processes for handling contingencies and emergencies requiring new regulations; an appreciation of the many possible criteria that might legitimately be used to distinguish high-priority from low-priority new regulations; and an annual ministerial regulatory agenda statement and debate in the House of Commons. In addition, consideration should be given to the question of whether such an agenda process should stand alone, or whether it should be appended to the existing tax or spending agenda process to avoid duplication in matters such as stakeholder consultation, or for other reasons. The annual regulatory agenda-setting process would have to be determined at the Cabinet level, either by a designated Cabinet committee on regulation or by processes similar to those that currently determine tax and spending priorities. This approach would anchor the process close to the prime minister and the minister of finance, and their departments and staff. However, on regulatory matters, there would have to be mechanisms to feed in S&T advice and expertise on risk, neither of which are part of the capacities and expertise of the prime minister or the minister of finance and their immediate supporting central agencies. That is the reason why some kind of Cabinet committee with a broader mandate for regulatory priority setting may be needed—keeping in mind, of course, that choices of Cabinet committee structure and mandate are entirely the prerogative of the prime minister. The purpose of this process would be, as with the taxing and spending process, to give at least some key ministers and officials some sense Chapter 5 143 of the volume of proposed new regulations bubbling up from below, and to allow them to set priorities as to which new regulations would proceed and which would not. As I have noted, departments already have some idea of which new regulations are queuing up and which are more important, and some screening will have occurred at that level. There are numerous coordination and capacity issues among regulatory agencies involved in almost all new regulations or in operational compliance. The committee could crucially flag and discuss these issues as the agenda took shape. That would not be an easy process, of course. However, it would be much more likely that the government would deal with complex regulatory coordination and capacity issues if ministers focused annually on a smaller sub-set of regulatory agenda proposals, rather than using the current highly uncertain and narrower one-regulation-at-a-time approach. The issue of defining regulation is an important one. As noted in the introduction to this study, overall federal rule making can be revealed and contained in laws, delegated legislation (the “regs”), guidelines, standards and codes. To keep the proposed regulatory agenda process manageable, it may make sense to focus only on the “regs” per se. However, the inclusion of new statutes warrants serious attention, for the simple reason that many new laws contain serious rule-making provisions in concert with delegated authority, which will in turn produce more “regs.” A provision for contingencies and emergencies would have to exist so that new regulations to deal with crises or hazards could still go forward from ministers or Cabinet, even if they were not on the annual regulatory agenda. A contingency budget exists in the federal spending process and there would have to be a functional equivalent for unforeseen regulatory requirements. It must also be stressed that normal emergency procedures in regulatory governance would continue at the operational level for product approvals, compliance and enforcement under existing regulations. Thus, any operational crises or contingencies would still be handled in the established ways under numerous regulatory programs. Such operational 144 Red Tape, Red Flags actions occurred in relation to the Canadian “mad cow disease” crisis, the SARS crisis and other hallmark crises. In other words, it must be kept fully in mind that the regulatory agenda being discussed in this chapter refers to new regulations. The criteria for setting a regulatory agenda are also important. The arguments mounted as to why a given new regulatory proposal should be ranked high and should proceed to adoption will, without doubt, reflect the same diversity of rationales, values and ideas as arguments for new tax and spending proposals. The minister of finance and the prime minister control tax priority setting, whereas new spending, though tightly controlled by a few ministers, does involve a formal and informal bidding process by all ministers. Proposals for new regulations would undoubtedly come from many ministers as well. The rationales and criteria would include risk assessments of diverse kinds, and levels of real and perceived severity. I will return to this issue in the discussion later in this chapter on the rationale for additional institutional change via a suggested arm’s-length Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. There would also, in any given year, be criteria related to electoral promises, international obligations, regional pressures, and numerous health, safety, environmental and sustainable development values. In a complex Cabinet of more than 30 ministers representing a federation, the criteria for pride of place on the regulatory agenda will be as diverse as they are for spending and taxation. As indicated above, agenda setting inevitably reflects a mixture of political and economic rationality, but also involves tactical and opportunistic behaviour by political and economic players inside and outside of government taking advantage of windows of opportunity. Current federal regulatory policy already contains quite diverse criteria reflecting political, economic and public interest concerns. Any reading of past budget speeches and documents, and of SFTs, reveals a mixture of criteria—some hard and rigorous, and some softer and based on the fine arts of tactical political judgment. Criteria that included relative regulatory burden and benefits, degrees of risk, international obligations, election promises and normal political judgment Chapter 5 145 would—and should—undoubtedly apply. Regulatory agenda setting would be very much a function of complex political–economic judgments, as is the case with spending and tax agenda setting. The notion of an annual regulatory agenda speech or statement could also be part of a proposed federal regulatory agenda. This could be a stand-alone statement by a lead minister or the prime minister leading to a two- or three-day debate in the House of Commons, as happens after the budget speech and the SFT. The intent here would be to draw attention to, and focus debate on, the government’s strategic regulatory agenda, in somewhat the same manner as the current taxing and spending process. The SFT, presented every 18 months or so, would also reflect the annual regulatory agenda statement. Finally, it is important to raise the issue of whether such an agenda process should be a stand-alone one or one that is appended to the existing tax or spending agenda process so as to avoid duplication in matters such as stakeholder consultation, or for other reasons. I argue strongly for a separate process to ensure that complex regulatory regime issues and overlap issues can be examined more seriously. However, others may well argue that the process should be married to these other agenda-setting processes. If so, tying it to the budget speech and its prior processes may make sense. If it was tied to the current formal spending plans and priorities process discussed earlier, that process would need major reform to capture the regime-level issues that are increasingly the norm in modern regulation. An annual regulatory agenda would need to link new regulations with current ones to minimize duplication and overlap, and to ensure that the right agencies and departments are accountable, responsible and transparent. Related Institutional Reform: A Regulatory and Risk Review Commission While the discussion of an annual regulatory agenda is the key feature of this chapter, consideration also needs to be given to the previously 146 Red Tape, Red Flags mentioned need for an arm’s-length expert Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. The premise of this chapter is that governments will, and should continue to, use both the requirements of the federal regulatory policy and the new Directive on Streamlining Regulation. Periodic, oncea-decade regulatory reform exercises will also undoubtedly be used. The analysis above also stresses that the criteria that might inform agenda setting are likely to be varied, and that the federal government and its departments and agencies—pressured by their varied stakeholder groups and constituencies—will largely drive the suggested agenda-setting process. The case for a complementary Regulatory and Risk Review Commission is based on the argument that external, arm’s-length expert public input is needed. Some of this advice is needed to provide a regular overview of regulatory regime changes and challenges emanating from new international pressures and from emerging technologies. Specific advice is also needed on risk profiles that cut across government and society, which may then require regulation, or other forms of non-regulatory action or information. At present, risk assessment is necessarily and properly focused in departments and agencies, but there is scarcely any capacity for forming views and setting priorities related to real and perceived risk across the government. Such a review commission would not be involved in any regulatory approval decisions, nor should it function as some kind of appeal body. (These tasks would properly be the job of front-line regulators and the courts.) Rather, it would review information, conduct research and advise regulators on the above types of cross-governmental developments, all linked to the nature of regulatory regimes in the innovation age. Such an advisory commission could also assemble—and advise the government on assembling, through agencies such as Statistics Canada—further systematic data on regulatory growth, regulatory change, and related risk matters and issues, both on Canada itself and on how Canada compares with other countries. The implication in this argument for complementary institutional change is that the commission would be a federal agency. However, a case could be made for it to be a federal–provincial agency funded by both levels of government. Chapter 5 147 Conclusion This chapter has examined further what is wrong with the current federal approach to regulation in relation to the growing importance of complex regulatory regimes, as discussed in the three case studies. It has also explored the question, “If an annual regulatory agenda dealt only with new regulations, how would it help address the issues raised in previous chapters?” Canada needs a much more strategic approach to modern regulatory governance in the innovation age. Accordingly, this chapter has made the case for establishing a fully functioning federal regulatory agenda and agenda-setting process, one that more transparently sets annual priorities for new regulations through a Cabinet-centred process. It has also argued that consideration should be given to establishing complementary institutional change via the suggested Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. The red-tape and red-flag realities of regulation in the innovation age make such strategic regulatory agenda-setting and review capacities essential. So, too, do the interacting effects of the three forces discussed in Chapter 1 and highlighted in the case studies. Because most rule making involves multiple departments and agencies within the federal and provincial governments, as well as at international levels, an agenda-setting process is needed to focus on the most crucial areas of regulation; to achieve better coordination, economic efficiency and innovation; to eliminate duplication wherever possible; and to maximize the benefits of regulation. Complementary external review capacity is also needed. The chapter has looked broadly at how regulatory decision making compares with taxation and spending decision making—two federal processes that are anchored in an annual agenda-setting process. It has explored whether there is an existing, latent regulatory agenda that is simply not very transparent, and whether aspects of it could be built upon to create a more explicit regulatory agenda. 148 Red Tape, Red Flags The analysis above also laid out briefly what a formal regulatory agenda and an agenda-setting process might look like and how they might work. In addition, it has made the case for the advantages of such a system compared with the status quo. It also raised the issue of whether such a process could be appended to existing processes, such as the tax and spending agenda processes. The analysis concludes that there is still a strong case for a separate regulatory agenda process to deal with growing regulatory regime-level issues, with the three interacting forces and pressures examined earlier, and with the need for more transparent democratic regulatory governance. Chapter 5 149 6 Conclusion T his study has examined the nature and growing importance of complex regulatory regimes and the changing dynamics of redtape and red-flag regulation in the innovation age. The three key interacting forces examined in Chapter 1 are propelling regulatory change, shifting the shape and contours of regulatory regimes and their mix of multiple agencies, statutes, processes and stakeholders at the federal, provincial, international and local levels of regulatory authority. The study has also examined overall federal regulatory policy and periodic federal regulatory reform exercises with a view to assessing the capacity of federal policy and reform to deal with complex regulatory regimes in an innovation era. Three conclusions flow from the analysis, each of which draws on the findings of the three case study regulatory regimes and the related weaknesses of regulatory policy and past reform exercises: The red-tape and red-flag regulatory issues that concern Canadians are no longer in as continuous opposition to each other as they once were. Rather, in the innovation age and to a much greater extent than before, they are integrative and reinforcing in nature. In many specific situations, business and social stakeholders have a mutually reinforcing interest in efficiency and in effective risk management. Some tensions, of course, still exist between these two concerns, but the configuration of political interests and their concerns can be on either side of the red tape/red flag equation, in different circumstances and situations. What is wrong with current federal regulatory policy is that it is based far too much on a one-regulation-at-a-time approach combined with periodic, once-a-decade regulatory reform exercises. More effective ways of managing complex regulatory regimes are needed. Regime-level issues need more focused examination, both when new regulations are proposed, and when product and project approvals—and compliance and enforcement issues—are addressed under existing regulations. Chapter 6 153 The federal government needs to develop a transparent annual regu- latory agenda whose priorities and resource needs are announced, debated and agreed upon annually in ways that already broadly exist for governmental taxation and spending decisions and plans. For some time, governments have had overall policies on regulation and how regulation should be conducted, and have thought about aspects of regulatory agenda setting. However, they have not even come close to establishing a transparent annual regulatory agenda that would complement their spending and tax agendas. The architecture of federal regulatory governance also needs access to more transparent, arm’s-length expert advice provided through a suggested Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. Red Tape, Red Flags: Complex Interactions, Integration and Role Shifts With regard to the first conclusion, my analysis in Chapter 1 showed how three interacting forces have had a major impact on the nature of regulatory governance. Fast, complex economic and technological change, by its very nature, creates both new products and production processes whose proponents are anxious to find an unencumbered route to market success. However, it also inevitably creates concerns about health, safety and the environment. Consumer demands for increased access to new products are premised on a significant reduction of red tape but always with red-flag concerns never very far from the surface. My discussion of the science-based nature of risk regulation—and thus of the overall interactions between regulation and innovation— highlighted the delicate balancing acts involved. Caught up in these complex processes are core concepts such as “safety” and “risk-benefit,” where different notions of what red flags and risk might actually be are central, often unclear and often subject to variation in particular situations. 154 Red Tape, Red Flags In the not-so-distant past, the conventional summary political logic suggested that business was the stakeholder that most often expressed concern about red tape. Environmental and consumer NGOs, on the other hand, were the stakeholders most associated with concerns about red-flag health, safety and fairness issues. Government regulators and their political masters seemed broadly to accept this summary logic of core regulatory politics and were, in some sense, caught in the middle. In varied and more specific ways, each of the three case study chapters revealed the changing red-flag and red-tape dynamics, integrating forces and roles. More and more, business, NGOs and Canadians overall are concerned about similar red-tape and red-flag issues. Integrative and reinforcing behaviour can increasingly occur in specific situations where innovative products are involved, because both business interests and NGOs have a common interest in reducing red tape and in getting access to efficacious products that are safe or that can be sensibly managed on a risk–benefit basis. Of course, spirited debates still arise between these groups. However, it is important in regulatory governance not to instinctively pigeonhole these stakeholders into easy and often unconsidered political categories. Specific situations and cases do matter, as do the nature of the risks and where interests sit. Modern regulatory governance requires good casebased political intelligence in these situations, rather than simplistic prior categorization. In both the drugs–public health and biotechnology–IP regime case studies, speedier access (less red tape) to safe or risk–benefit-managed drugs and diagnostic tests (red flags) was increasingly the concern of business, NGOs and Canadian consumer-citizens. “Access” became the watchword of all of these stakeholders, albeit in different specific ways and contexts. The fact that core stakeholders could shift sides on particular redtape and red-flag aspects of complex regulatory regimes was revealed in the biotechnology–IP case study, where businesses’ excessive patenting was seen by some stakeholders as growing red tape for patients, Chapter 6 155 health professionals and public researchers. Businesses, meanwhile, saw the protection of the integrity of the patent system and the latter’s role in enhancing innovation as their red-flag concern. The analysis of the energy–environment regulatory regime also showed complex role adoptions on either side of the red tape/red flag equation. In the realm of environmental assessments, NGOs often historically sought slower deliberative processes when energy projects were oil, gas or nuclear projects. However, when energy projects involve renewable energy such as wind, solar and other sources, NGOS often prefer speedy decision making and assessments, because these forms of energy are seen as more sustainable. None of the above arguments is intended to imply that there are no remaining tensions and traditional divisions in the red-tape and red-flag debates. What is central to the argument is that stakeholder dynamics are often more integrated than in the past, in particular circumstances. Circumstances do matter, as does the design of particular regulatory instruments to deal with problems where key players have complex interests, not simplistic ones. Therefore, regulatory regimes—in both their new regulation aspect and their operational approval and compliance aspect—need to be able to both observe and respond to such changes. In these fluid situations, interests shift in complex ways; effects are dispersed among many phases or aspects of regulation; and, almost inevitably, multiple regulators are as involved in interpreting these political interest groups’ shifts as they are in the science and economic aspects of regulation. The Gaps in Current Regulatory Policy and Governance The discussion in chapters 1 and 5 of federal regulatory policy, the current regulatory decision-making process and the way that process evolved through add-on elements of suggested good regulatory practice showed what is wrong with the basic federal one-regulation-at-a-time 156 Red Tape, Red Flags approach. Exhortations to consider interdepartmental coordination were a later part of these official policy “add-ons,” but they were still essentially buried inside a one-regulation-at-a-time logic. The analysis of past formal regulatory reform initiatives showed how each initiative dealt in its own way, in different time periods, with different accumulated problems of regulation and regulatory governance. In the case of the recent federal smart regulation initiative, these problems were more explicitly linked to innovation itself and to the growing need for Canada to compete in the knowledge-based economy. It must be stressed that there is nothing inherently wrong with having such approaches in the architecture of Canadian regulatory governance. Guidance on how to make each regulatory decision is undoubtedly needed and useful. Periodic, once-a-decade regulatory reform can be useful. Governments will undoubtedly use such exercises in the future, if for no other reason than that new governments of different partisan makeup will want to conduct even larger periodic reviews. However, what is wrong is that neither of these ways of addressing regulation and governing capacity on regulatory regime matters can now keep pace with actual regulatory change or with the speed and complexity of economic and technological change. Again, the three regulatory regime case studies showed the inherent sluggishness and inertia of decision making, as problems accumulated but spilt over the cracks of these two partial approaches. It took a decade or more to even begin to deal with the backlog and approval times lag in the drugs–public health regime, and even longer to begin to address the overall common drug policy issues tied to access via the funding of new drugs. Part of the problem was also the lack of scientific capacity to review new drugs. The biotechnology–IP regime analysis showed similar delays of a decade or more in dealing with the different notions of access related to both bio-health products overall and genetic diagnostic tests. The energy–environment regime chapter also showed the absolute debacle of Canada’s climate change responses, regulatory and otherwise, over a decade or more, and the snail-like responses to the reform of environmental Chapter 6 157 assessment law and assessment processes, both within the federal government and among levels of government. There was a clear lack of political leadership to tackle the climate change issue, partly because changes would adversely affect some individuals and some regions of Canada more than others. The standard response to these kinds of inertia is often that they are just the price to be paid for democratic processes. The problem is that real democracies must also be able to make timely decisions that address real problems in effective ways. The current regulatory architecture does not do this, nor is it particularly democratic in the sense of direct accountability and transparency, given the nature of complex regulatory regime problems and characteristics. A Strategic Regulatory Agenda and Related Institutional Reform Canada needs a much more strategic approach to modern regulatory governance in the innovation age. Accordingly, this study has made the case for establishing a fully functioning federal regulatory agenda and agenda-setting process, one that more transparently sets annual priorities for new regulations through a Cabinet-centred process. If the federal government on its own approves about 50 new major regulations a year, then a linear projection for the next decade is 500 new regulations. If parent laws are added, these numbers of new rules are even greater. At present, it is virtually impossible for ministers, Parliament, or Canadians and their stakeholder groups to have any clear sense about what regulatory priorities are or ought to be. It is virtually impossible to have a strategic view of regulation. An annual regulatory agenda is needed to complement and complete the current regulatory governance architecture. This analysis has also made the case for some kind of arm’s-length Regulatory and Risk Review Commission. This body would support cross-governmental 158 Red Tape, Red Flags regulatory agenda setting with ongoing, arm’s-length expert advice and data dealing with regulatory regimes, priorities and risk profiles. The red-tape and red-flag realities of regulation in the innovation age make such a strategic regulatory agenda and such cross-governmental advice a necessity. So do the interacting effects of the three forces discussed in Chapter 1 and highlighted in the case studies. Because most rule making increasingly involves multiple departments and agencies within the federal and provincial governments, as well as at international levels, an agenda-setting process is needed for the following reasons: to focus on the most crucial areas of regulation; to achieve better coordination, economic efficiency and innovation; to eliminate duplication wherever possible; and to maximize the benefits of regulation. Accordingly, I have looked briefly at how regulatory decision making compares with tax and spending decision making—two federal processes that are anchored in an annual agenda-setting process. This study has discussed whether there is an existing latent regulatory agenda that is simply not very transparent, and whether aspects of it could be built upon to create a more explicit regulatory agenda. The analysis has also laid out briefly what a formal regulatory agenda and agenda-setting process might look like and how they might work. In addition, it has made the case for the advantages of such a system compared with the status quo. It has also raised the issue of whether such an agenda process could be appended to existing processes, such as the tax and spending agenda processes. Overall, I conclude that there is still a strong case for a separate regulatory agenda process to deal with growing regulatory regime-level issues and with the three interacting forces and pressures examined. There are, of course, counter-arguments and cautionary tales about such an agenda for new regulations. As we saw in Chapter 5, all systems of political agenda setting are partly rational in a formal sense but are also tactical and opportunistic, as players take advantage of moments of opportunity. That is certainly true of the tax and spending Chapter 6 159 agenda-setting processes and of overall SFT agenda-setting processes as well. But no one would argue that the federal government should make its spending or tax decisions without an agenda-setting process— in short, by making tax and spending decisions simply on the basis of a one-tax-at-a-time or one-expenditure-at-a-time approach. A spokesperson for the telecommunication industry (see the three commentaries at the end of this volume) pronounced such an agenda idea as “overkill” and impractical. She preferred a sectoral approach. Many problems of regulation do need attention at sectoral levels. An annual regulatory agenda is not a panacea, but it is, nonetheless, a key missing part of the overall regulatory architecture. A sectoral-only approach easily translates into excessive stovepipe regulatory governance and is, quite literally, impractical given the growing cross-governmental need for a strategic view of regulation. Thus, if anything is overkill, it is the status quo governance of regulation. The status quo is by no means a fully effective system for dealing with complex regulatory regimes and strategic rule making, nor for handling red-tape and red-flag issues and diverse notions of risk and riskbenefit that exist across a complex government, economy and society. Many regulatory departments and agencies may well oppose a formal regulatory agenda on the grounds that it would centralize new rulemaking decision processes too much. Regulators also enjoy their stovepipe status and independence; feel that their work is already complex; may think that the current federal policy on regulation is already too complicated; and may believe that they are already pulled and stretched by the varied demands of stakeholders, international treaties and other governments. However, in the final analysis, they are part of one government, be it federal or provincial, affecting all Canadians. There are, of course, many regulatory jurisdictions such as British Columbia, where efforts to reduce regulatory burdens are underway and, as noted in Chapter 5, where a premier-led strategy is in evidence. The federal Smart Regu­ lation review process also yielded some useful changes and recognition of problems. 160 Red Tape, Red Flags Still others—inside government and outside it among NGOs—may fear that a regulatory agenda may simply mean, on balance, less regulation. For other interest groups, that would be a virtue. In both cases, having a formal annual agenda and new advisory institutions increases the odds that new regulations will be based on a more considered assessment—at the centre of elected government—of the most important regulatory challenges, linked to assessments of relative risk, of complex regime issues, of the precise kinds of rule making that should be applied, and of the costs and benefits relative to lower-ranked priorities. It must also be stressed that new regulatory proposals can also include proposals to reduce rule making or, indeed, to deregulate in specific industrial or social realms. Red-tape and red-flag regulatory challenges are entrenched in the innovation age. Canada’s current regulatory governance system is not at all well suited to addressing the country’s strategic need to deal with complex regulatory regimes and the changing stakeholder coalitions on both sides of the red tape and red flags regulatory coin. Canada’s political democracy and its economic prosperity will both be diminished unless more open regulatory agendas and risk review institutions become a normal part of the way we govern ourselves in the innovation age. Chapter 6 161 From the Lecture: Richard Thorpe’s SIRP Lecture Comments These commentaries were delivered at the Scholar-in-Residence lecture on May 23, 2007, in response to a presentation by G. Bruce Doern that consisted of excerpts mainly from Chapter 5 of the larger report published in this volume. I t’s a pleasure for me to be here tonight to bring British Columbia’s perspective to Professor Doern’s presentation on Regulation in the Innovative Age. If one accepts his assessment that one-third of the role of the government is making regulations and enforcing compliance, then a strategic, government-wide approach to regulatory reform is essential. Economic competitiveness depends on it. And, as Professor Doern has noted, citizens are very concerned about the mounting red tape at all levels of government. The cost to individuals and business of complying with regulation rivals the cost of taxation—both of which are key competitiveness factors. If you accept this fact, which I do, then you must agree with Professor Doern that governments should put as much effort into their annual regulatory agenda as they do into their annual fiscal agenda. Allow me to share with you British Columbia’s experience in addressing regulatory reform. Since 2001, our government, under the leadership of Premier Gordon Campbell, has developed what we believe to be one of the most innovative and comprehensive regulatory reform initiatives. British Columbia’s approach to regulatory reform has included the elements of an effective regulatory reform agenda, one that both the Canadian Federation of Independent Business and the Advisory Committee on Paperwork Burden Reduction have recommended that other governments follow. Premier Campbell’s vision and commitment was to reduce our regulatory burden by one-third over a three-year period. We knew we had to understand the magnitude of the regulatory burden in British Columbia, and thus we needed to establish a baseline count of that burden. Our journey began with a very comprehensive account of all regulatory requirements contained in legislation, regulation and interpretive policies in British Columbia. To achieve our goal of a one-third reduction over three years, each minister was required to develop a three-year regulatory reform plan as part of his or her ministry’s threeyear service plan—what are known in the private sector as business plans. Priority was given to regulations viewed as impeding economic competitiveness; but, at the same time, we committed to ensuring that health, safety and the environment were not compromised. From the Lecture: Richard Thorpe’s SIRP Lecture Comments 165 Regulatory reform achievements are reported publicly through British Columbia’s annual budget, and quarterly reports for all ministries are posted on my ministry site. As well, each ministry must provide a regulatory update in its annual service plans and a monthly report to Cabinet. I keep the scorecard, and it is discussed every month in Cabinet. Achieving a positive regulatory environment requires the highest level of political commitment—in our case, Premier Campbell’s vision and commitment. For our government’s first two and a half years, regulatory reform was given its own portfolio, with the Minister of State being responsible for deregulation (similar to the January 2007 appointment by Prime Minister Harper of the Honourable Gerry Ritz as Secretary of State for Small Business and Tourism). We’ve succeeded in cutting more than 41.19 per cent of regulatory requirements faced by citizens, small business and industry in British Columbia—a total of just under 158,000 regulations. That’s a lot of red tape. British Columbia is committed to being Canada’s most smallbusiness-friendly jurisdiction. Reducing red tape plays a key role in achieving this goal and helping us with our goal to lead the nation in job creation. In April 2006, British Columbia and Alberta signed the British Columbia–Alberta Trade Investment Labour Mobility Agreement. This agreement, over time, reconciles regulations and standards to ensure that businesses and workers in both provinces have seamless access to a larger range of opportunities across sectors. A recent report by The Conference Board of Canada has suggested that lowering tariff trade barriers could help narrow the Canada–U.S. productivity gap. In view of this and other regulatory innovations in our province, last year the Canadian Federation of Independent Business presented Premier Campbell with an award recognizing him for his leadership and for British Columbia’s groundbreaking work in promoting regulatory reform and accountability. More recently, recognition of British Columbia’s efforts came in the March 2007 federal budget, in which Minister Jim Flaherty said, “We will reduce the business paper burden 166 Red Tape, Red Flags by 20 per cent by November 2008, following the excellent example set by the government of British Columbia.” It’s very encouraging to see the federal government acknowledging British Columbia’s efforts. British Columbia is committed to working with the Prime Minister, ministers Flaherty and Ritz, and their government to enhance Canada’s and British Columbia’s global competitiveness. Our government’s ongoing commitment is to have a zero per cent increase in regulation—a target we continue to meet and, in fact, exceed. As I mentioned earlier, health, safety and environment remain paramount. In fact, we have maintained environmental integrity and improved environmental protection through a new Environmental Management Act. This Act came into force in 2004, replacing a 23-year-old Waste Management Act. A key aspect of it is the adoption of a scientifically based, principled approach to environmental management, one that ensures sustainability, accountability and responsibility. This allows our province to address the cumulative impacts of pollution, penalize violators quickly and encourage environmentally responsible behaviour through innovative new approaches. Building on our success, we recently introduced Track II of our Regulatory Reform Plan. It’s called Citizen-Centred Regulatory Reform—or, as I like to call it, Saving People Time. The Saving People Time approach is all about saving time from the perspective of the individual and small business. Small businesses have told us that they want to spend less time on red tape and more time on what’s important: running and building their successful small businesses. We agree. We’re seeing the results of this at work in British Columbia, where small business is booming. Fifty-seven per cent of all private sector jobs come from the small business sector in British Columbia, which is seeing record-setting job creation and the lowest unemployment rate in 30 years. For 15 quarters, nearly four years now, British Columbia has led Canada in business confidence. Two-thirds of British Columbia’s small businesses and industry expect stronger performances in the year ahead, and more than one-third expect to hire more staff. This has been reported by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business. From the Lecture: Richard Thorpe’s SIRP Lecture Comments 167 Through our continued work on regulatory reform, we will continue to take steps, in partnership with small businesses, to help turn their expectations into reality. In October 2006, I received the government’s first Small Business Roundtable Annual Report. This permanent Small Business Roundtable has provided a very successful platform for ongoing dialogue with small business in British Columbia. The small business lens, a key recommendation of the Small Business Roundtable, was developed to ensure that the needs of small business are fully explored each and every time our government proposes new or amended laws and regulations. It poses to ministers and public servants a number of tough questions related to regulatory criteria, and is included in our regulatory checklist. We are also building exciting new streamlining initiatives with other levels of government. In April, British Columbia and the federal government became the first jurisdictions to sign a new five-year memorandum of understanding regarding BizPal. This user-friendly, time-saving tool builds on our government’s commitment to cut red tape and make it faster and easier to do business in British Columbia. BizPal is a partnership of three levels of government—municipal, provincial and federal—working together to reduce the regulatory burden on individuals and small businesses. In British Columbia today, each and every one of our 23 ministries is currently working on time-saving and streamlining regulatory reforms to help to improve the lives of our citizens. To conclude, British Columbia has seen success in regulatory reform, but there is still more work to be done, especially by all levels of government. British Columbia believes in partnerships, and we have indicated to the federal government that we are willing to work on a provincial–federal pilot project to look at how overlap in regulations (in such areas as mining, fisheries, oceans and the environment) can be addressed. Working together, governments can save citizens and businesses time, money, confusion, unnecessary paperwork and red tape, while enhancing Canada’s competitiveness. 168 Red Tape, Red Flags With respect to Professor Doern’s powerful presentation, British Columbia actually has fixed election dates, fixed Throne Speech dates and fixed budget dates. So British Columbia fully supports the view that governments need a strategic approach to regulatory reform. We believe very strongly that this strategic approach should be tied directly to individual ministries, government annual business plans and the annual budget process. We do not believe that it should stand alone; you’ve got to link the money and the accountability on regulatory reform or, in our opinion, it won’t happen. This, we believe, will result in accountability, transparency and real regulatory reform that will build Canada’s competitiveness. Thank you very much. From the Lecture: Richard Thorpe’s SIRP Lecture Comments 169 From the Lecture: Elizabeth May’s SIRP Lecture Comments These commentaries were delivered at the Scholar-in-Residence lecture on May 23, 2007, in response to a presentation by G. Bruce Doern that consisted of excerpts mainly from Chapter 5 of the larger report published in this volume. F ollowing Minister Thorpe’s remarks, I want to give you a small insight into my own experience with small business. My father was a manager and the CEO of our vast empire, which at that time was a restaurant and gift shop on the Cabot Trail, employing 30 people seasonally. He took up the challenge, and he enjoyed all the notices he got from the Government of Canada. He enjoyed them so very much that he thought he should share them with the travelling public. So he maintained a bulletin board right next to our coffee shop that was titled “The Government of Canada Never Sleeps,” and every time he received a new notification of some new regulatory provision (some of these were just regulations, some of them were the tariffs on Bangladeshi textiles and whatever else was going on), he would post it. He also kept track of how much of his time as a small businessman was spent doing the work that he regarded as his time working for the government unpaid, and that was generally about a third of his time. In other words, I was not brought up to love laws and regulations. I do, though, coming from the environmental movement, probably stand for the red flags side of the red flags–red tape equation—which is to say, by all means let’s get rid of the red tape, but let’s not so undo those essential functions of government that we actually lose our ability to regulate and to protect human health and the environment at a time when these issues are increasingly critical and our margin for error is increasingly small. So it becomes a real challenge to get regulations right. There have been various government efforts—I am sure they have been advertised as smart regulation—often seen and sometimes misunderstood by the environmental movement, I think, as translating into deregulation. There are certainly ways in which we can reduce unnecessary burdens. I want to focus on another aspect of the paper, though, and that’s the question that Professor Doern raised about there not being a central process within government—a failure to centralize what’s going on. I put it another way as well: there is a lack of policy coherence, and not just in regulation setting. The fiscal framework often is set for different reasons than the regulatory framework, and that’s just speaking about the federal government. When you look at the lack of policy coherence around certain of the issues with which I am most familiar, you are looking at one From the Lecture: Elizabeth May’s SIRP Lecture Comments 173 set of rules and regulations at the federal level, sometimes another at the provincial level, sometimes one as well at the municipal level and sometimes another at the international level. This does tend to create a pulling in different directions and in­effective regulation, which by definition can’t be smart regulation. We see this happening in a number of ways, and I want to speak about them specifically. But before that, I also want to suggest that we shouldn’t just oppose tough regulations and competitiveness as if they are working in opposition. We know from the studies conducted by Harvard Business School Professor Michael E. Porter that those countries and those companies that have the highest required achievement of regulatory standards in terms of the best environmental performance are also the most competitive. This is not a real surprise. It means that the companies that avoid regulation, that continue to pollute, that plead for extra time, are the ones that are not modernizing; they are falling behind. And by definition, if you are falling behind, you are not competitive. So we need to uncouple these issues, making sure we have not just adequate but robust policies in regulatory reform, and fiscal frameworks that work together with policy coherence to deliver the best results with the least excess red tape. It’s important to see that serving the public interest in health and safety and the environment is very congruent with the public objective of competitiveness. So what’s the key driver for regulation? What is the primary driver for public policy when, for instance, you go to regulate pesticides? Well, there really isn’t a primary driver. If you ask the minister of health, who now has the responsibility for the Pest Control Products Act, you will probably hear that protecting the health of Canadians is his or her number one concern. But that isn’t evident when you look at the decisions that are made. There is also the pressure from the agricultural community: “We need to be competitive because on the other side of the border something might be regulated and we want to get access to it and maybe it will be better.” Meanwhile, you also have pressure from the pesticide manufacturers. I was once on the advisory committee to the minister of health, an advisory committee that was dominated by representatives of user groups and industry, and I was the only representative from an environmental group. I was really struck when the only medical doctor in the group said, 174 Red Tape, Red Flags “Don’t you find this a little funny as an advisory group? How would it be if the government structured a group to advise the minister of health on the problem of peanut allergies, and the com­mittee struck was composed of the people who grew peanuts, the people who grind up peanuts, the people who sell peanuts, the people who market peanuts and one doctor?” So there is an imbalance there. There are so many competing interests, even in this one area of pesticide policy, and that is just at the federal level. We have the Pest Control Products Act, and manufacturers may well say that there are onerous regulations. There are certainly hoops through which they must jump, but the actual effectiveness of our regulations in protecting public health is very much in doubt. Every time the Commissioner for the Environment and Sustainable Development (under several different watches) examined whether this system was working and protecting Canadians’ health, he or she found the regulatory system sadly wanting—it wasn’t driven by protecting public health. So that’s why you see the provincial governments coming to their own decisions: “Well, it may be regulated federally, but we don’t have to use it provincially, because we can make our own determination of whether it’s safe or not.” Then you get to the municipal level, where increasingly the most proactive preventative work is being done through bylaws to say, “We don’t want chemicals that cause cancer used on our lawns.” Then you get to another whole level of government, which are the bi-national or regional trade agreements. Ever since the North American Free Trade Agreement, Canada has tried to harmonize our regulations with the United States. And every time, there has been a harmonization toward the maximum residue levels of pesticides on fruits and vegetables. Canada insists that our fruits and veggies have to have less pesticide than U.S. law allows, but the harmonization means that Canadians are allowed to have more pesticide in their fruits and vegetables, never that people in the United States should have lower levels in order to harmonize with us. That is quite different from, for instance, the way the European Union trade bloc works, where the highest standards are the ones that must be adhered to. On another topic (which could easily be more than the whole 10 minutes I have)—the climate issue. We are not seeing effective use From the Lecture: Elizabeth May’s SIRP Lecture Comments 175 of regulations in dealing with our Kyoto commitments. Obviously, we are not seeing any effort at all to reach the Kyoto commitments; that is now official government policy. But there was one item that I thought worth raising tonight, which is the so-called economic study that Minister John Baird brought forward. If any of you happened to look at it, you will have noted that there were a number of assumptions built into that study about how much it would cost to reach Kyoto targets, and the assumptions predetermined the outcome that it would mean economic ruin. One of the things that was stated was that “for the purposes of this economic study, we will assume no new regulations on anything”— with the excuse that it takes too long to pass regulations. That’s quite interesting when you have a government body, Environment Canada, with the mandate to act on an international, legally binding treaty. Of course, I do think that there was a bias in the way the assumptions were selected—that is, in saying essentially that we are not even going to try to use regulations for the purpose of the study, because they take too long. That’s an admission of failure. If you are going to have a proper regulatory process, and you are going to engage, as Bruce Doern’s paper says, you need to have public input. There is a very clear demand by Canadian citizens, I think, for transparent regulations that protect public health and the environment. And that demand is a good deal stronger than their demand for, for instance, new products (unless those products are connected to new drugs needed for medical treatments). So we do need to get to a better system. My plea actually goes beyond Bruce Doern’s excellent proposal that we have a regulatory agenda that’s systematic and well developed; that meets expectations throughout the government system and the private sector; and that protects the health and environment of Canadians. I would add that the linkages to the Speech from the Throne in the fiscal framework also need to be thought through. And please—as we have heard Minister Thorpe say is possible—we need federal–provincial cooperation to ensure that regulations coming forward are both sensible and coherent. Thank you. 176 Red Tape, Red Flags From the Lecture: Janet Yale’s SIRP Lecture Comments These commentaries were delivered at the Scholar-in-Residence lecture on May 23, 2007, in response to a presentation by G. Bruce Doern that consisted of excerpts mainly from Chapter 5 of the larger report published in this volume. I want to thank Anne Golden and the Conference Board for putting on a very stimulating talk and for inviting me to be a part of this discussion and presentation. Given my background, I really appreciate the opportunity to comment on Bruce Doern’s lecture on Regulation in the Innovation Age, and the issue of regulatory reform in particular. I may as well say at the outset that while I applaud the red tape/red flags distinction in the paper, I have some big issues with the manner in which he is proposing to set a regulatory agenda. Let me start by saying that regulation, as you know, is a topic that’s near and dear to my heart, and to those of my colleagues at TELUS. And when I use the word “dear,” I don’t mean “loved,” I mean “costly,” because for us, regulation is all about the cost of doing business. Let me also start by positioning my comments in the context of how we at TELUS see regulation in the innovation age. We are really living, I think, what Dr. Doern is lecturing about, in that regulation is happening in an incredibly innovative environment. We in the telecom business certainly see that innovation as a key to success and staying alive. If you just look around, I am sure that some of the innovation we have provided at TELUS is in your pockets as we speak, in the form of a small handheld device that lets you make phone calls, surf the Internet, now watch TV, listen to music, navigate to unfamiliar locations and, of course, check your e-mail—all of that from almost anywhere in the world. That innovation isn’t cheap. It takes billions of dollars of investment and the willingness to undertake that kind of risk capital. Just as a small example of the kind of money we are talking about, we bought a national wireless network for $6.6 billion, at a time when others were exiting the wireless business. That risk has paid off for us big time, but the point is a simple one: innovation and the willingness to make those kinds of investments are about seeing the right signals in the marketplace. For us, that is about an environment governed more by market forces than regulation. The second reason that regulation is near and dear to us at TELUS is that for many years we have continued to labour under what we call the yoke of restrictive economic regulation, while our competitors—cable companies who are offering telephone service—have been free to take From the Lecture: Janet Yale’s SIRP Lecture Comments 179 market share away from us completely unencumbered by any regulatory restrictions, whether on their pricing, marketing, restrictions in terms of service, or whatever. When we can’t make our best offers to customers, those costs of regulation are borne in fact by consumers in the form of higher prices and less innovation. Government has begun to recognize that this kind of regulation ultimately hurts consumer welfare and productivity. Still, I think we have miles to go in terms of regulatory reform. We welcome fighting for consumers in the marketplace, but we have had to spend a huge amount of our attention on fighting the regulator for the freedoms that would allow us to compete. The good news for us and for the telecom sector, as you may be aware, is that we expect to be deregulated for local service in 2007, hopefully by the end of the summer in markets where we face competition from two or more carriers. That is going to be a real sea change in the telecom environment. As you may know, long-distance wireless and Internet services were deregulated years ago. Wireless service, in fact, has never been regulated; and from our perspective (I hope you will agree), innovation has really been a hallmark of that service. Internet access is another service that’s never been regulated, and Canada is a world leader when it comes to high-speed Internet access. So the bottom line is really simple: look to competition, not to regulation, when you want to see innovation and investment. That is where I am coming from when I look at papers like Dr. Doern’s. I was pleased, frankly, to hear him acknowledge that regulation can harm or prevent product, process and institutional innovation. That’s certainly been our experience with regulation. But the heart of his proposal is for federal and provincial governments each to create an annual regulatory agenda, whereby new regulations from across departments and agencies would be aggregated annually and priorities determined through a central process at Cabinet level, with regulatory statements that would be debated for up to three days in the House of Commons and provincial legislatures. When I hear about that kind of process, I think “overkill.” In my view, the centralization of new regulatory initiatives would be very cumbersome and very time consuming, in light of the diverse and complex array of 180 Red Tape, Red Flags government activities. You just have to hear Elizabeth May’s discussion of the single issue of trying to get a coordinated regulatory strategy around the environmental agenda, and pesticides in particular. You think about trying to do that for every department and every issue, and I think the thing would collapse of its own weight. But more importantly, I think, it’s not necessary to approach it in that way in order to achieve the rationale for Dr. Doern’s approach: the goal of a visible and openly debated opportunity to discuss regulatory changes that are addressed in an integrated way. Let me give you an example. Canada has recently gone though a major review of the regulatory regime that governs the provision of telecommunication services, a review that led to much less reliance on regulation and much greater reliance on market forces in the provision of telecom services. The primary goal of that change was to foster innovation. In April 2005, the Government of Canada appointed a three-person Telecommunications Policy Review Panel to review the regulatory framework for telecom service. The panel conducted public policy forums, considered more than 200 submissions and issued its final report in March 2006. In this process, there was visible and open debate, and the proposed changes were debated in an integrated way. The panel heard, for example, from the Competition Bureau, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), and 10 provincial and territorial governments. Reflecting all of those recommendations, in December 2006 the government for the first time issued a policy direc­tion to the CRTC under the Telecom Act, directing the Commission to rely on market forces to the maximum extent feasible. That direction was considered by Cabinet, and I think it is fair to say that Cabinet considered its direction in relation to its other regulatory priorities. Last month, the government issued the CRTC another key direction—to implement the new test for deregulation. Prior to doing so, the government invited public comment on the direction and a parliamentary subcommittee held public hearings. Again, there was visible and open debate, with integration in terms of input from the Competition Bureau, the CRTC and many other parties. This is not to say that, due to the much-improved approach to telecom regulation, everything is fine and nothing more remains From the Lecture: Janet Yale’s SIRP Lecture Comments 181 to be done. What I would like to leave you with is the notion that a comprehensive review of the regulatory framework for particular industries—as was done for telecom—is a terrific idea. We have advocated a similar approach in the area of broadcasting regulation, and the new Chair of the CRTC, Konrad Von Finckenstein, has launched a review of the existing statutory and regulatory framework for broadcasting. It’s being done quickly, in four months, and I would anticipate that the document will be the subject of a public consultation process in which a variety of issues can be addressed in order to develop a prioritized agenda for regulatory reform in broadcasting services. In addition to thinking things through on a sectoral and crossgovernment basis, I believe that the process of developing and proposing new regulations would benefit from what we do as a matter of course in the private sector: namely, disciplined risk assessment. Risk assessment brings more certainty and predictability to new areas of risk—to so-called red-flag issues—by assessing the likelihood that a particular event or action will occur, and then assessing the impact associated with that particular risk. The results of a risk assessment can be used to develop priority areas for regulatory intervention, including the elimination of regulation where necessary. That kind of disciplined risk assessment is a matter of course for us at TELUS. Every year, we conduct an enterprise-wide risk assessment that uses interviews and web-enabled surveys to develop and prioritize our approach. We integrate the results of that exercise into our strategic planning process and our internal audit and compliance programs. This ensures that when we think about deploying scarce resources on priorities, we are doing it where the need for risk mitigation is highest. In my view, that kind of comprehensive and disciplined approach to risk assessment would bring similar benefits to governments, particularly with red-flag issues such as the environment and health care. That’s just some food for thought. Let me conclude by congratulating Dr. Doern for focusing our attention on the need for regulatory reform and the role of regulation in the innovation age. Thank you very much. 182 Red Tape, Red Flags From the Lecture: Panel Discussion and Q & A Allan Gregg: Bruce, I want to start with you. You heard Janet: she said that your proposal for regulatory review is overkill, and there are other ways of doing this. She uses the example of sector-wide or industry-specific regulatory reviews that put an industry under the microscope and make assessments. What is your response? Bruce Doern: Well, they are not mutually exclusive. There are many things you need to do at a sectoral level, and I agree it is difficult. [Creating] a regulatory agenda is, in my view, inherently not more difficult than what we now do for taxation and spending. Spending is a very aggregated process. There is a smaller set of ministers who actually make the final choices in a massive bidding process on the spending side. So if one is thinking about a regulatory agenda system, one has to imagine what kind of politics would occur around it. Some sectors might not like some of the politics, because if they are not on the high-priority list, that may itself be a problem. I think one has to imagine ways in which interest groups would behave and ministers would have to talk to each other in moving toward having a more explicit agenda. I am not arguing that this is an easy process, because they will have to figure out some fairly tough priorities. The other view that I want to state is that the usual way one tends to think about how governments function in a 30-member Cabinet is that they have a system that’s there to make decisions and to set priorities. But in fact, a lot of the time what they are doing is finding new ways to say “no.” They have to say “no” most of the time because otherwise we’d have 10 times the taxation, 10 times the spending and 10 times the regulation. In fact, there are processes now where they try to figure out ways to say “no”—but my proposal would make it much more explicit, and they would have to defend their positions much more demo­cratically and transparently. From the Lecture: Panel Discussion and Q & A 185 Allan Gregg: Elizabeth, when it comes to environmental protection, is all regulation good regulation? Elizabeth May: No, of course not. Some regulations are not—if, for instance, you were to regulate in a way that curtailed the ability of companies to seek the very best technology and move faster than the bare minimum. I think you need to pick a bit of both. You need regulations to ensure that the laggards are not so far behind the curve that they are actually contributing to creation of pollution havens. At the same time, though, you want regulations and a mix of fiscal instruments that will allow innovation to happen, because that’s what’s going to make the difference. The companies that have set the pace on previous environmental issues are the ones that decided not to wait for the regulations but to do more than what’s required of them. If regulation required you to make a certain minimal effort and no more, if it didn’t leave you free to excel, that would be bad regulation. But you generally can get regulations right, particularly if you have taken the time to think through what the policy objective is. Picking up on Bruce’s point, one thing that happens a lot is that there are people within a bureaucracy working on new regulations who are largely uncoupled from their political masters. And then you end up having a politician who thinks, “I want to make an announcement—what’s lying around?” Regulation for the purpose of press release is a very bad idea. Rick Thorpe: I totally agree with that—and I am not just a politician but also an elected official, a mirror reflection of those who have voted for me three times. I want to pick up on something Elizabeth said on the environmental side, because we’ve been doing this now for about six years in British Columbia, and we did have some people say that the world would come to an end; surprisingly, it hasn’t. You may be familiar with a very bad contaminated site in British Columbia, the Britannia 186 Red Tape, Red Flags Mine site, which has been there for a long time through many governments. If we had approached it in the traditional way through the public service, I think the clean-up bill was estimated at $75 million, which probably would have turned out to be about $125 million. Instead, we had somebody come forward with an innovative, creative public partner proposal. The minister of the environment, the minister responsible for integrated land management and the Treasury Board (of which I am the vice-chair) all looked at it, and we decided to go with a new, innovative approach. I think it ended up costing $10 million; and more importantly, we got a disaster cleaned up. I think that was what Elizabeth was saying in suggesting that our approach can’t be so restrictive, and that we have to take innovative approaches. With respect to environmental and climate action, we in British Columbia believe that we can achieve a reduction of 33 per cent in greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2020, and that doing so can actually turn out to be a great economic activity for us. It just depends on how you want to look at the picture. We look at it and see the blue sky. Allan Gregg: Janet, same kind of question with a different spin: when it comes to the telecommunication sector, is all regulation bad regulation? Janet Yale: No, absolutely not. I think there are three buckets of regulations generally: economic regulation (which is what you can and can’t do in the marketplace in terms of retail); regulation on prices and the terms and conditions under which you offer service; and technical regulation that enables our networks to talk to each other and interconnect appropriately. There are all kinds of technical rules that have to exist to make sure that we don’t duplicate investment just because we can’t agree on how to connect our networks. Social regulation is about all of the things we do from an affordability perspective to help those who have disabilities and need special telecom services. From the Lecture: Panel Discussion and Q & A 187 It’s the economic regulation piece that I was most focused on in terms of whether or not you can increasingly rely on market forces rather than regulation to protect consumers. At the end of the day, regulation is only a substitute for market forces where there isn’t sufficient competition to protect consumers. I don’t quarrel with the need for a regulatory agenda and I don’t quarrel with the need for a systematic approach to eliminating red tape. To your point, Rick, it may be great to have government mandating the elimination of red-tape regulation and making that a priority, because then you can make it happen. I am saying that in telecom and broadcasting, there can be the will to undertake that overhaul of red tape. I don’t see why it has to be done on a governmental, enterprise-wide basis. It’s just happening, sector by sector, in the sectors that I worry about. Maybe this is not true so much on red-flag issues, where you need a strategic framework in which to do it; but I don’t think you need to wait for a government-wide view of where red tape needs to be eliminated in order to get moving sectorally on its elimination. Bruce Doern: Well, there are lots of things that do go on at a sector level, so I think that’s quite appropriate. However, there is a difference when you start thinking about what the government does. For example, let’s suppose you have 50 regulations a year and you decide to really focus on 10 of them for the following year or two. Those 10 will have different consequences for different industries. They have different economic impacts and they have different social impacts. It seems to me, on balance, especially in the era we are living in, that you need to have a strategic view of what those ought to be; and it may then mean that you don’t work on other regulations that year. Allan Gregg: That’s your argument for why government should reduce its agenda—so it can set priorities in a strategic way? 188 Red Tape, Red Flags Bruce Doern: Corporations do it in a certain way already, so the other argument is that governments need to be strategic in the same sense. It’s an addon to the current system. I don’t think that it in any way prevents lots of other good things from being done sectorally or in the environment. They will live lives of their own—for example, on things like product approvals. There’s a lot that can be done there that doesn’t require new regulations, just better coordination. Elizabeth May: I want to come back to one of the things that Janet said about economic regulations and social regulations, and how they are different. This is a big difference when it comes to the issue of market forces. The reason we need to have regulations to protect human health and to reduce greenhouse gases, and the reason why regulations are a tool that people look to so often, is that we’ve allowed these to be externalities in the marketplace. If we had full-cost accounting, if we had carbon taxes, if we got the prices right, it would be a lot easier to say there should be a lesser regulatory burden. Then it’s more like getting the prices right, and letting market forces prevail. Just to make the obvious point: the reason that social and economic regulations are so different is that when you come to the issue of “Is this chemical carcinogenic?” that’s a good enough reason to ban it, even if the farmers want it. These are real-life examples where human health has lost out. But if you are able somehow to internalize the cost of cancer in society into the regulatory decision making, it might be very different. Rick Thorpe: I want to talk on two points. One is the social aspect. Unfortunately, when you start on regulatory reform, some people think you are trying to hurt those people who can’t defend themselves. I can tell you that as a minister, but more importantly as an MLA, I had a constituent, a disabled constituent, who phoned me one day with an issue having to do From the Lecture: Panel Discussion and Q & A 189 with homeowner grants, and what he was telling me that the government was doing didn’t seem fair to me. As I started unpeeling the onion, I really became quite irritated, because five or six different ministries in our government are dealing with people with disabilities, but we found out they’re not actually talking to each other. So we undertook our Citizen Centred Reform Track II—or, as I call it, Saving People Time. I pushed, as an economic minister and a revenue minister, for something to be done with folks with disabilities, because of my constituent. Five ministries were involved, and there were 17 different items that the individual had to deal with. We brought those ministries together, breaking down the silos. There is now one contact point, and it takes 10 minutes. So it can be done. The biggest reason why I believe strongly that it has to be done is that if you let it be a stand-alone thing, it becomes the flavour of the day and will just go away some day; but if it’s integrated and part of a budget process, then that’s scrutinized and people have to put forward their regulatory accounts and what they’re trying to achieve as part of a business plan. In British Columbia, the government is a $40-billion organization, the largest organization in British Columbia. Why should we not be disciplined in how we approach these issues? I don’t know what the federal budget is now, but I’m going to guess it’s $200 to $225 billion. But there will be resistance—this was our experience in British Columbia, I don’t know if it’s going to be in Ottawa— because when you start talking about regulatory reform, you’re talking about change, and the first thing that goes through people’s minds when you talk about change is, “I’m going to lose my job.” It’s not about people losing their jobs, but it is about providing effective customer service and protecting health care, safety and the environment. It’s a journey that I believe strongly that the country has to get on, and we’re very hopeful that Canada will work with British Columbia on a couple of pilot projects we’ve proposed on mining, the environment, and fisheries and oceans. It can be done, but Professor Doern is right: it’s not an easy task. 190 Red Tape, Red Flags Allan Gregg: Janet, you said in your remarks that at TELUS you go through a systematic assessment of risk, and that this same methodology could be applied to all regulatory frameworks. Would you expand on that? Janet Yale: Obviously, you have to look at the need for interventional regulation. The issue is whether it’s an end or a means. When I talk about risk assessment, it’s not looking at risk in isolation from a strategic agenda. We have our three- to five-year strategic plan and our business plan for the year. We make that risk assessment in the context of our business agenda and our business priorities; it’s not about looking at risk in isolation from the key imperatives that we’re trying to deliver. We identify all of the risks that we think might stand in the way of our being able to achieve our business plans and priorities. We do internal and external stakeholder assessments, and we look at the likelihood of those risks materializing, as well as the impact if those risks happen. Every year, for example, we have weather impacts, and we have to have disaster recovery plans in the case of floods. Some of the risks are weather related and some aren’t. And then we have risk mitigation plans with respect to all of the risks that have a high potential of occurring and significant impacts if they do occur. Allan Gregg: And the same process could be used to gauge the benefits or liabilities of regulation? Janet Yale: That’s right. Then you can say “Okay, these are the areas that need priority attention.” I was thinking of them in the context of health care and the environment, where you can use that kind of approach to say, “Given all of the issues we can focus on in the area of health care or the environment, which are the ones that, based on a disciplined assessment, require us to get the prior claim on resources?” At the From the Lecture: Panel Discussion and Q & A 191 end of the day, if you don’t know what your top priorities are relative to the list of 200, you don’t really have a sense of what you’re trying to accomplish. Allan Gregg: Bruce, one of the areas in your lecture that interested me most was your comment that you can set up a framework and a process, but when it comes to science-based regulations—that is, regulations that require science to say whether this is good or bad, needed or not needed—the government often does not have the capacity to make those evaluations, because it just doesn’t have the scientific horsepower. Given that, what kind of framework or process is going to make any difference? How do you deal with that? Bruce Doern: My overall argument is that there needs to be significant reinvestment in the government’s in-house science and technology in order to be able to do some of that work. The problem with the science and technology is that the higher up in the government you go, the less literacy there is about science. It’s just the way the system is. I think it’s very closely related to the business of an agenda on the red-flags side of things. Try to imagine if any one of you were appointed tomorrow in the federal government as minister of risk, and you had to figure out what risks you would actually focus on as a government in the next three or four years. Well, in a sense, when the red-flags part of the agenda emerges, it could be that groups of ministers would in fact be talking, because it literally could be the risks of climate change on the one hand versus the risks of bungee jumping on the other, because somebody may want laws against bungee jumping. Now that ought to be a fairly easy choice as to which you may give priority, but nonetheless there is a whole series of issues at play, some informed by good science and some where the science is controversial. And you certainly have to have government investment in the science. I don’t think you can rely, in most areas of regulation that governments have to do, on placing all your marbles on either universities or industries to do this 192 Red Tape, Red Flags kind of work. The research, the science and the monitoring have to be available in a timely way to governments and decision-makers. It has to be framed in a certain way. That’s why the in-house science really has to be supported, even if there is no political capital, no votes in that at all. That has to be a part of this equation—building up the scientific capac­ity and then having some kind of agenda that flows from it. Q & A With Audience Audience member: Professor Doern, when considering a public policy, one often hears that the greatest consequences are the unanticipated ones. Can you comment on how your system might, in fact, do better at taking into account the risk mitigation [element] of regulation, which I assume often has the same type of unintended consequence? Bruce Doern: All analytical government regulatory impact assessments and so on would be geared to narrowing those senses of unanticipated consequences. You never get it perfectly, because the issues do change and new products come up that you’re not familiar with. But I do think that the probabilities of getting more of this risk caught increase the more that you spend serious time on it. By that, I mean ministers spending some serious time even though they’re busy, as well as senior officials. Of course, interest groups, NGOs and business groups will also be engaged, because once they know they’re either ranked high or low on this kind of list, stuff will happen. One has to imagine that kind of process occurring, along with lots of other issues that will be raised across a wide spectrum of activity. And Minister Thorpe is quite right that you can have a strategy for regulatory priorities that says we are really going to focus on this area in the next two or three years, which does in turn have budgetary implications. It means that if you really are going to staff this area, the budget has to kick in with the resources. One of my biggest concerns about federal regulation is that Canada has been From the Lecture: Panel Discussion and Q & A 193 signing onto all sorts of international treaties and agreements that we nobly wish to achieve, but there is no automatic follow-up with a consideration of what kind of resources you will need to do a really good job on execution, as opposed to a sort of good job. We need a change in terms of paying more attention to this arm of government. Audience member: Every year, the Canadian government is bringing hundreds of thousands of new Canadians with skills and talents into this country. However, we know that most of these people are not utilizing their skills in the job market. Do you think that this is a problem of red tape or something else? We new Canadians don’t understand if it is something else. Rick Thorpe: We do many of our immigrants a disservice in attracting them to Canada and not telling them what they have to go through when they get here. I don’t think that’s right. In British Columbia, we are working very closely with the minister of immigration to see how we can streamline the processes. I don’t think that if people can show that they are qualified doctors, they should be driving taxicabs in Vancouver or Victoria. It’s been a long-standing issue, and we have to work with the professionals in the province. I think we have to start by providing a better service to people before they come into the country, so that they are made aware of some of the hurdles they’ll encounter in fulfilling their dreams. We should also be doing better at understanding what the hurdles are, so we can get rid of them. In British Columbia and Alberta, we need more and more very qualified technical people in all walks of life, so it’s an issue that we should be addressing. Elizabeth May: It’s an issue that occupies some space in the Green platform as well, and we’re very concerned about it. I don’t think it comes down to red tape in the sense of government red tape; it would take government creativity to undo the red tape of professional associations. I have been 194 Red Tape, Red Flags a lawyer, admitted to the bar in Manitoba and then in Nova Scotia and Ontario, and I had to go through many hoops that really didn’t have to do with my legal qualifications. They had to do with creating barriers to entry to the legal profession in Ontario because I was a mere lawyer in Nova Scotia. The reality of closed shop unions from one province to another is quite extreme. As for one country to another—well, the medical profession wants to retain its standards and the legal profession wants to retain its standards. We could commit to work with the professional associations to find a way to expedite the accreditation of qualified new Canadians so they can gain positions as doctors and nurses and architects and engineers and all the things that they’re skilled and trained to do. I will mention one flip side that niggles at my brain as a concern: we mustn’t, in a wealthy country like Canada, rob developing countries of their best brains and bring them here as cheap and fast additions to our professional societies. We must expedite it for new Canadians, but at the same time be cognizant that we don’t want to rob developing countries of their best people. We need to ensure that we raise the standards of living for everyone globally through the elimination of poverty, which is a much bigger question than what we are talking about tonight. Audience member: This is a question for Elizabeth May: Could the Government of Canada, specifically Environment Canada, improve its effectiveness vis-à-vis protecting the environment with fewer regulations—and, if so, how? Elizabeth May: It certainly could. I want to pick up a point here that gives me a chance to agree vigorously with what Bruce Doern said about science capacity. Environment Canada is a shadow of its former self in terms of its brainpower, its ability to understand the science and the issues that it has to oversee. We have lost core competence in science throughout the Government of Canada, but in Environment Canada in particular. When I worked in the minister of the environment’s office 20 years From the Lecture: Panel Discussion and Q & A 195 ago, we had some national experts in their field; we no longer have that, we have managers. This is not a universal state—there is some good science—but there is not anything like what we used to have. Regulations aren’t even the beginning of the issue of what Environment Canada needs to do. We are no longer even tracking the issues well enough to be able to put together the kind of state-of-the-environment reports that used to be done 15 years ago and that were cancelled in the budget-slashing of the early ’90s. We couldn’t put together that kind of report now because we are not tracking the same indicators. We don’t know about freshwater health across Canada, since we have closed the research stations. So it’s not a question of fewer regulations to do a better job. I think we need to have a better capacity within the department. We certainly could do a better job if we enforced the regulations we have. We could do a much better job if we reviewed all the regulations to see if they are consistent with one another. And why don’t we focus on best practices? Global best practices—for instance, in pesticide regulation—would say that we should regulate fewer products, understand them better and know what we are doing, rather than being on a constant treadmill of how many new pesticides we should register. We’re behind the eight ball with thousands of commercial chemicals that have not been properly assessed. 196 Red Tape, Red Flags