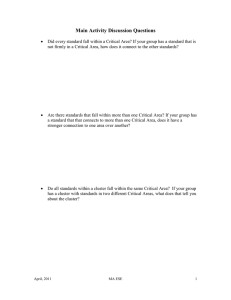

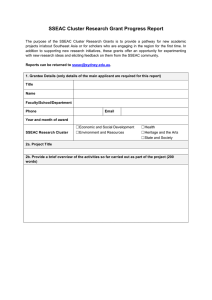

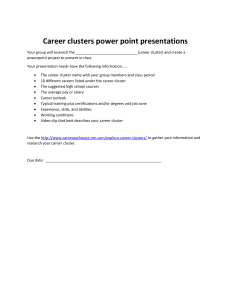

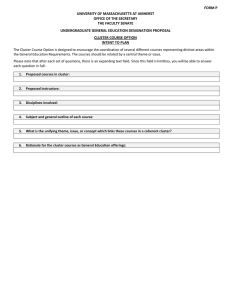

A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read MARGARET TROYER Harvard University Background: Research has shown that reading motivation is correlated with achievement. Studying motivation in older students is particularly important as reading motivation declines over the course of elementary and middle school. However, current research largely fails to reflect the nuance and complexity of reading motivation, or its variation within and across contexts. Purpose: This mixed-methods study investigates whether distinct reading motivation/ achievement profiles exist for adolescents and what key levers foster adolescents’ motivation to read. This approach was designed to produce more generalizable results than isolated case studies, while providing a more nuanced picture than survey research alone. Research Design: Seventh graders (n = 68) at two diverse public charter schools serving lowincome students were surveyed regarding reading motivation and attitude. A cluster analysis of survey results and reading achievement data was conducted. One student per cluster was selected from each school for additional qualitative analysis (n = 8), and students and teachers (n = 2) were observed and interviewed. In addition, cross-case and cross-school analyses were conducted to determine key levers which may promote students’ motivation to read. Conclusions: This study suggests that four distinct reading achievement/motivation profiles may exist. In addition, teachers have substantial influence on adolescents’ motivation to read. Teachers could benefit from gathering more information about students’ reading motivation and from promoting feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Introduction Two-thirds of American eighth graders cannot read and comprehend text at a proficient level (National Center for Education, 2015). This means that a majority of middle school students cannot, for instance, adequately provide and support an opinion about relationships between ideas in a text, or integrate details to provide an explanation. On average, AfricanAmerican and Latino students enter high school with literacy skills three years behind those of Asian and White students, and students from low-income families enter high school with literacy skills five years behind those from high-income families (Reardon, Valentino, & Shores, 2012). Clearly, something must be done to improve adolescents’ literacy outcomes – especially in schools serving low-income students and students of color. Teachers College Record Volume 119, 050306, May 2017, 48 pages Copyright © by Teachers College, Columbia University 0161-4681 1 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) One promising avenue in improving these outcomes may be to promote students’ motivation to read, as much research has demonstrated an association between reading motivation and achievement (Guthrie, Wigfield, Metsala, & Cox, 2004; Guthrie, Wigfield, & Perencevich, 2004; Mucherah & Yoder, 2008; Taboada, Tonks, Wigfield, & Guthrie, 2009). For instance, an analysis of NAEP data indicates that engaged reading predicts reading achievement even more strongly than mother’s education level; in other words, students whose mothers had not graduated high school, but who were at least moderately engaged readers, earned higher achievement scores than disengaged readers whose mothers had higher levels of education (Guthrie, Schafer, & Huang, 2001). Thus, encouraging students’ motivation to read may be an efficacious route to improving their reading skills. Studying motivation in older students is particularly important as reading motivation declines over the course of elementary and middle school (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000; Kelley & Decker, 2009; Wigfield, 2000). This decline is not inevitable, as teachers may play a critical role in supporting the development of adolescents’ motivation to read (De Naeghel et al., 2014; Legault, Green-Demers, & Pelletier, 2006). However, much current research overlooks the complexity and nuance of the relationship between motivation and achievement (Bundick, Quaglia, Corso, & Haywood, 2014). Furthermore, most large-scale survey research on reading motivation has taken place in schools that serve predominantly middle-class, White students (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004), despite the fact that low-income schools serving students of color have disproportionate numbers of struggling readers (Lesaux & Kieffer, 2010). Therefore, I undertook this study of seventh grade students’ motivation to read, in the context of racially diverse, low-income schools, in the hopes of finding ways in which teachers may adjust their instruction in order to enhance students’ motivation to read. The study is framed around the research questions: • Do distinct profiles of reading achievement and motivation exist for adolescents? • What are the key levers to fostering motivation to read in adolescents? To what extent does the relative salience of these levers vary systematically according to achievement/motivation profiles? 2 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Theoretical Framework Theoretical Perspectives on Motivation Reading motivation, defined as the “goals, values and beliefs with regard to the topics, processes and outcomes of reading” (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000, p. 405) is a complex construct which researchers have sought to define and operationalize in a number of ways. The work of the present study is informed by three major theories of motivation. Self-determination Theory Deci and Ryan (1985) distinguish between extrinsic motivation, which “refers to behavior where the reason for doing it is something other than an interest in the activity itself” (p. 35) and intrinsic motivation, “defined as the doing of an activity for its inherent satisfactions” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 56). These researchers claim that intrinsic motivation is driven by the innate need for three things: autonomy, relatedness and competence (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Autonomy means behaving with a sense of choice and exercising some control over the tasks one pursues. Relatedness describes a feeling of belonging or connectedness in interpersonal relationships. Finally, people seek activities which provide them with a sense of competence, or the belief that they will be able to succeed at a given task. Expectancy-value Theory Eccles and colleagues proposed that motivation is a function of, first, a person’s expectancy, or perceived probability of success (Eccles et al., 1983). This expectancy is influenced by the person’s “self-concept of ability” combined with his or her perception of task difficulty (Eccles et al., 1983, p. 82). Secondly, an individual’s motivation to engage in a particular task depends on how much he or she values that task. The researchers define three types of value: attainment value, which describes how important it is to a person to do well on a particular task; intrinsic value, or the enjoyment gained from the activity; and utility value, or how useful the individual perceives the task to be in achieving his or her future goals. Mindsets: A Social-cognitive Approach Dweck and Leggett (1988) asserted that people pursue specific types of goals: performance goals, which are oriented toward gaining approval and appearing competent, or learning goals, oriented toward working to increase skills and competence. These goals are linked with implicit theories of intelligence; individuals with an incremental theory 3 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) of intelligence, who believe that intelligence is “malleable, increasable [and] controllable” are more likely to set learning goals, while those with an entity theory of intelligence, believing that intelligence is fixed and unchangeable, are more likely to set performance goals (Dweck & Leggett, 1988, p. 262). Additionally, students who set performance goals are more likely to ascribe to an inverse relationship between effort and ability, believing that intelligent people can achieve success without much work, and that investing significant time and effort in a task reflects low ability. Conversely, students who set learning goals view effort and ability as positively related, since they believe that this effort will allow them to improve their skills. A Complex and Multifaceted View of Motivation Given the various and overlapping theories of motivation outlined above, the present study operationalizes motivation to read in accordance with the framework suggested by Schiefele and colleagues (Schiefele, Schaffner, Möller, & Wigfield, 2012). Based on their review of 20 years of both quantitative and qualitative empirical research on reading motivation, these researchers conclude that motivation to read is composed of nine distinct factors, theoretically rooted in both expectancy-value and self-determination frameworks. Like self-determination theory, Schiefele et al. distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. According to their research, extrinsic motivation has three components: recognition, competition, and grades. Intrinsic motivation consists of curiosity and involvement, meaning enjoyment of texts, or getting “lost in a story” (Schiefele et al., 2012, p. 433). Additional motivational factors include compliance, or “reading because of external pressure or assignments in school”; work avoidance, which is a negative predictor of motivation to read; self-efficacy, or a person’s perception of his or her own competence; and value or importance of reading (Schiefele et al., 2012, p. 433). Finally, motivation may also be either habitual or current. Someone who is repeatedly motivated to read demonstrates habitual reading motivation, whereas current motivation is context-dependent, and may be prompted by a specific text, topic or situation (Schiefele et al., 2012). Additionally, motivation is distinct from attitude and engagement. Attitude describes affect toward a task, and one may be motivated to read without liking to do so. Engagement is defined as “the act of reading to meet internal and external expectations” (Schiefele et al., 2012, p. 10), and may be behavioral, emotional or cognitive (Fredricks et al., 2004). Both motivation and attitude are addressed in this study. 4 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Relationship between Reading Motivation and Achievement Substantial research has demonstrated associations between reading motivation and reading achievement. For example, Mucherah and Yoder (2008) found that reading motivation was positively correlated with scores on the state reading assessment for sixth and eighth graders. In their study of seventh graders, Guthrie, Klauda, and Ho (2013) found that motivation predicted achievement both directly and indirectly through engagement with reading. In addition, Wolters, Denton, York, and Francis (2014) found that while gender and previous achievement explained about 13% of the variability in seventh through twelfth graders’ scores on a reading comprehension measure, motivation explained an additional 11% of the variance after controlling for gender and prior reading achievement. Thus, there is considerable evidence for a relationship between motivation to read, broadly defined, and reading achievement. Additionally, associations have been found between reading achievement and specific dimensions of motivation. For instance, in one study, intrinsic motivation, background knowledge and cognitive strategy use each independently explained variance in reading comprehension and reading growth in fourth graders (Taboada et al., 2009). In another study, which focused on 7- to 13-year-olds in England, good readers were more intrinsically motivated than poor readers, but the groups did not differ in extrinsic motivation (McGeown, Norgate, & Warhurst, 2012). In addition, Solheim (2011) found that reading self-efficacy and reading task value both uniquely predicted reading comprehension for fifth graders. This research provides support for the multifaceted nature of reading motivation, suggesting that particular dimensions of motivation—specifically intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and value—are associated with reading achievement, while other aspects, namely extrinsic motivation, may not be. Furthermore, longitudinal research suggests that motivation to read in early grades often predicts later reading achievement. One longitudinal study found that fifth-grade intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, engagement, and the importance students placed on grades significantly predicted eighth-grade reading achievement, even when controlling for gender, SES, race/ethnicity, and prior reading achievement (Froiland & Oros, 2014). In fact, the combined effects of intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and engagement were comparable to the effects of SES and far outweighed the effects of race or gender. Another longitudinal study in Germany found that third grade reading achievement positively predicted intrinsic motivation in fourth grade (Becker, McElvany, & Kortenbruck, 2010). 5 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) Controlling for third grade reading achievement, fourth grade intrinsic motivation strongly predicted sixth grade reading achievement. This suggests a bidirectional relationship between achievement and motivation, such that early reading success predicts increased motivation, which then predicts higher reading achievement later. Becker et al. (2010) also found that third grade reading achievement negatively predicted extrinsic motivation in fourth grade, which weakly negatively predicted sixth grade reading achievement, controlling for third grade achievement. This supports the finding, discussed above, that good readers tend to be more intrinsically motivated than poor readers (McGeown et al., 2012), and suggests that extrinsic motivation may not promote achievement. Further longitudinal research suggests that a reciprocal relationship may also exist between reading comprehension and self-efficacy in adolescents. Retelsdorf, Köller, & Möller (2014) found that fifth-grade reading achievement predicted reading self-efficacy in sixth, eighth, and ninth grades, while fifthgrade reading self-efficacy predicted reading achievement in sixth grade. Thus, longitudinal research demonstrates that reading achievement has a bidirectional relationship with both intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy, suggesting that improving either students’ reading skills or motivation may produce benefits in both domains. Research also suggests that the relationship between reading motivation and achievement is largely mediated through the amount one reads (Guthrie, Wigfield, Metsala, et al., 2004; Schaffner, Schiefele, & Ulferts, 2013). Schaffner et al. (2013) found that the positive effect of intrinsic motivation on reading comprehension was fully mediated by reading amount, and that when controlling for intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation negatively affected reading comprehension both directly and indirectly through reading amount. In another study, the association between reading achievement and amount of reading (both in-school and out-ofschool) was even stronger for African-American than for Caucasian students (Guthrie & McRae, 2012). Thus, when considering how to improve reading achievement, reading amount seems to be an important lever. Instructional context may play a vital role in increasing the amount that adolescents read (Francois, 2013; Ivey & Broaddus, 2001; Ivey & Johnston, 2013; Kirkland, 2011; Moje, Overby, Tysvaer, & Morris, 2008). Collectively, these studies show that students demonstrate more reading and higher levels of reading motivation in schools and classrooms which provide extended time for independent reading, free choice of texts, and, perhaps most importantly, texts to which students can personally relate. Teens tend to be motivated to read texts they can relate to on the basis of their racial and ethnic identities, or texts in which the main characters are experiencing struggles similar to those in students’ own 6 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read lives. Furthermore, students then engage in talk about these texts as a way of relating to peers and adults. Finally, teacher actions can also be significant levers in promoting adolescents’ motivation to read. De Naeghel and colleagues (2014) found that 15-year-old students’ perceptions of their teachers’ support for autonomy and relatedness were associated with higher levels of intrinsic motivation. Relatedness was the strongest predictor of intrinsic motivation, with autonomy support predicting motivation for girls, but not for boys. Individual and Group Differences in Reading Motivation Much of the existing literature to date has failed to address the complexity offered by a multidimensional understanding of reading motivation. Thus far, only a few studies have generated nuanced profiles or attended to individual and group differences in patterns of reading motivation and achievement. In one such study, Baker and Wigfield (1999) identified seven distinct motivational profiles among fifth and sixth graders, ranging from very low to high reading motivation. In the middle were four groups characterized as: (a) low importance; (b) competitive and work avoidant; (c) low competition and work avoidance, high importance and compliance; and (d) low competition, efficacy and recognition. In another study, Guthrie, Coddington, and Wigfield (2009) built composite profiles of fifth-grade readers by combining work avoidance with intrinsic motivation. They named the subtypes avid (high intrinsic/low avoidance), ambivalent (high intrinsic/high avoidance), apathetic (low intrinsic/low avoidance), and averse (low intrinsic/high avoidance) readers. Avid readers had higher achievement scores than all other subtypes, and Caucasian students were more likely to be avid readers. Finally, Klauda and Guthrie (2015) found that reading motivation and engagement predicted growth in achievement more strongly for advanced readers than for strugglers. These three studies describe nuanced reading motivation profiles; they demonstrate that different factors may be key motivational levers for different students, and that reading motivation may have various effects on outcomes. In some cases, these differences may be linked to membership in racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups. Given the gaps in literacy achievement, and the strong relationship between achievement and motivation, it is important to understand the ways in which all children—particularly those from less advantaged social groups—may be motivated to read. None of these three studies included both reading achievement and motivation in creating profiles; thus, the present study expands the work of identifying achievement and motivation profiles, as well as considering how motivational levers may be best adapted to the varying needs of these groups. 7 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) Reading Motivation in Adolescence Studying motivation in older students is particularly important as reading motivation declines over the course of elementary and middle school (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000; Kelley & Decker, 2009; Wigfield, 2000). Only 21% of 13-year-olds read daily for enjoyment, as compared to 44% of 9-year-olds (Baker, Dreher, & Guthrie, 2000). Some research suggests that these declines in reading motivation may be due to declining feelings of competence. For example, a longitudinal study of students’ beliefs about their competence in reading, and the value they placed on reading tasks, showed that competence beliefs were highest in first grade and declined over time (Jacobs, Lanza, Osgood, Eccles, & Wigfield, 2002). Although girls’ and boys’ competence beliefs were the same in first grade, boys’ declined more rapidly than girls’, so that by sixth grade, girls demonstrated higher competence beliefs. The value the students placed on reading tasks also declined, but the students’ declining competence beliefs explained a large proportion of the decline in task value; although boys placed less value on reading than girls did, the gender difference in competence beliefs explained more than half of this difference. Feelings of competence may decrease with age as children’s assessment of their own abilities in reference to others becomes more accurate, either through increased perceptiveness, or through teachers’ explicit comparison of children (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000). Students’ feelings of relatedness and autonomy may decline with age as well, due to the poor person-environment fit of middle school (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). The texts selected in middle school often are not culturally relevant, especially to boys and students of color, and therefore some students may find the content difficult to relate to and disengaging (Kirkland, 2011). In addition, while middle school teachers sometimes grant students autonomy, the relationship between autonomy and motivation is usually reciprocal, meaning that the least motivated students are least likely to be given autonomy in selecting texts or activities (De Naeghel et al., 2014; Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000). Therefore, it is no surprise that as a group, adolescents are less motivated to read than younger children. Measuring Reading Motivation Empirical information about reading motivation is generally obtained through either large-scale surveys or case studies, each of which presents some drawbacks. Surveys measure only habitual motivation, treating reading motivation as a stable construct, despite evidence 8 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read that individuals’ motivation varies both between and within contexts (Alvermann, 2001; Dressman, Wilder, & Connor, 2005; Ivey, 1999; Neugebauer, 2014). In addition, surveys rely on self-report out of context, depending on a level of abstract thinking which may be difficult for adolescents. Case studies, on the other hand, emphasize context and individual difference; however, they are not generalizable and fail to provide clear implications for instruction. Present Study In order to further shed light on the construct of reading motivation, and to bridge the gap between survey and case study research, I conducted a mixed-methods study of reading motivation and achievement in the context of low-income urban schools, guided by the research questions: • Do distinct profiles of reading achievement and motivation exist for adolescents? • What are the key levers to fostering motivation to read in adolescents? To what extent does the relative salience of these levers vary systematically according to achievement/motivation profiles? Groups of seventh graders (n = 68) at two diverse public charter schools in the Boston area were given the Motivation to Read Questionnaire (Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997) and the Survey of Adolescent Reading Attitudes (McKenna, Conradi, Lawrence, Jang, & Meyer, 2012). A cluster analysis of the survey results, along with reading achievement data, was conducted in order to identify common motivational/academic profiles. One student per cluster was selected from each school for supplementary qualitative analysis (n = 8), and students and teachers were observed and interviewed, in an attempt to uncover factors that motivate particular groups of students to read. This approach was designed to produce results that are more generalizable than isolated case studies, while expanding and elaborating on the identified profiles to provide a more nuanced picture than would be possible through survey research alone. Methods Study Sites Two public charter middle schools in the Boston area were selected as sites for this study. Both schools serve diverse populations, with high percentages of low-income students (see Appendix A). Both schools have relatively high reading achievement, with more than 60% of students scoring proficient or above on the state standardized test. However, the two 9 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) schools have very different instructional contexts. School A is part of a national network of “No Excuses” schools, and provides a highly structured environment, with a stated emphasis on managing behavior. Their literacy instruction takes a traditional form: seventh graders read whole class novels with a focus on classic texts typically taught at higher grade levels, e.g., Lord of the Flies (Golding, 1955), Of Mice and Men (Steinbeck, 1937). These novels are taught largely through round robin reading, and students are expected to engage in “interactive reading,” using a writing utensil to track and underline the text being read aloud. School B uses a modified reading workshop model, where students spend one class period per week independently reading self-selected texts. Assigned whole-class novels tend to be contemporary young adult fiction, e.g., Make Lemonade (Wolff, 1993), The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (Boyne, 2006). There is no school-wide behavior management system, and, to the outside observer, students appear to engage in off-task behaviors more frequently than in School A. School B appears to better reflect the contextual factors which encourage reading motivation, discussed above; therefore, one might hypothesize that students in School B would demonstrate more reading, and more motivation to read, than students in School A. The contrasts in culture and instructional models in these two schools provide interesting grounds for investigating reading motivation among adolescents. Participants The study included 68 seventh graders from diverse ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, attending one of the two participating schools. All students for whom parent permission was obtained, and who provided assent, participated. Complete data was obtained for 60 students. The sample was 42% male and 58% female; 7% Caucasian, 62% African-American, 20% Latino, 7% Asian, and 5% mixed-race or other. This demographic breakdown is representative of urban public schools in this geographic area. One teacher from each school was also observed and interviewed; both were Caucasian females, pseudonymed Sarah (School A) and Amanda (School B). Based on my analysis of survey results, I conducted follow-up qualitative analysis of four students per school, one from each cluster (n = 8), whose individual results closely mirrored the profile of that cluster (see Table 1). This multiple case study design allowed for both literal replication (wherein students from one cluster are expected to produce similar results) and theoretical replication (in which students from different clusters are expected to produce contrasting results), allowing me to develop theory around factors which motivate students to read (Yin, 2014). 10 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Table 1. Interview Participants’ Pseudonyms, Race, Gender, and Home Language School A Teacher Cluster 1 Cluster 2 Cluster 3 Cluster 4 School B Sarah, Caucasian female Amanda, Caucasian female Lily, Latina female Charles, African-American male English and Spanish Haitian Creole and English Zoe, African-American female Kevin, African-American male English Haitian Creole and English Danny, African-American male Mariana, Latina female English and Cape Verdean Creole English and Spanish Alesha, African-American female Dashawn, African-American male Jamaican Patois English Measures Reading Achievement Each school provided reading achievement data for participating students, including students’ 2013 scores on the state standardized test (MCAS), as well as their scores on the first interim assessment (IA) of the 2013–2014 school year. Interim assessments are designed to mimic the format and content of the MCAS. Reading Motivation and Attitude Surveys. All student participants took the Motivation to Read Questionnaire (MRQ), which uses 53 items on a four-point Likert scale to measure eleven dimensions of motivation (Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997). In order to address attitude, out-of-school literacy, and digital literacy, participants also took the Survey of Adolescent Reading Attitudes (Conradi, Jang, Bryant, Craft, & McKenna, 2013; McKenna et al., 2012). The SARA is an 18-item survey using a six-point Likert scale to measure attitudes toward academic versus recreational reading, and digital versus print reading. Students completed these two surveys during a regular literacy class period. Classroom observations. After identifying focus students, I conducted multiple observations of each student in their English/language arts classes. I conducted a total of approximately 20 hours of observation over the course of three months. Each teacher taught multiple sections of English, 11 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) and target students were not distributed evenly across sections. I conducted more observations of classes with a greater number of focus students; therefore, I observed each student for a total of between two and seven hours, and each teacher for a total of between eight and eleven hours. Over the course of these visits, I observed each student engaged in multiple units of study with different assigned texts, in both reading- and writing-focused lessons, and with a substitute as well as with their regular teacher. During these observations, I recorded detailed field notes about students’ behavioral engagement or disengagement with reading, the assignments and instruction which were taking place, and students’ interactions with teachers and peers. I used these observations to develop a deeper understanding of the contexts within which these particular students make choices about whether to engage in reading (Yin, 2014). Additionally, the observations informed my interviews, allowing me to ask students concrete questions about specific observed behaviors, rather than asking them to think abstractly. Student and teacher interviews. As soon as possible after my observations, I conducted semi-structured interviews with target students to determine which factors they believed led to their level of motivation in that particular context. Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes, and interview protocols were tailored to each cluster, to investigate specific motivational factors which seemed most salient to that cluster (for example, since Cluster 2 demonstrated below average beliefs about the importance of reading, they were asked: “Tell me about a specific time when you read something that was important to you.” Since Cluster 3 demonstrated below-average compliance, they were asked: “How often do you finish your reading assignments, completely and on time?”) Finally, the two teachers were interviewed to gather their perceptions of target students’ reading motivation and factors leading to it; these interviews lasted approximately an hour. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Analytic plan. First, I analyzed descriptive statistics of survey results and achievement measures. Next, I conducted a cluster analysis, selecting data points for inclusion based on both theoretical and empirical considerations. Although the MRQ measures eleven dimensions of reading motivation, my analysis was confined to the nine factors theoretically justified by Schiefele et al. (2012). Additionally, a reliability analysis was conducted to determine internal consistency (see results in Table 2; see also Appendix C for item-level psychometrics). Cronbach’s alphas for each of the nine dimensions of motivation described above ranged from 0.52 to 0.76. Alphas for the three larger constructs (intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and self-efficacy) comprised of combinations of these dimensions ranged from 0.80 to 0.86, and alphas for the 12 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read four attitudes measured by the SARA ranged from 0.64 to 0.85. Alphas for all constructs may be considered “adequate” to “very good” except compliance and importance (Kline, 2011, p. 70). Importance is measured by only two items on the MRQ; therefore a true reliability analysis is impossible. The correlation between the two items is 0.57 (p < .001) , indicating a moderately strong relationship. Although the construct of compliance fails to empirically demonstrate adequate internal consistency in this study (a = 0.52), the variable was retained in my analysis for theoretical reasons given its importance as a dimension of reading motivation (Schiefele et al., 2012). Thus, I entered standardized data for each student for each of these measures of reading motivation and attitude, as well as the two measures of reading achievement, into a cluster analysis. I conducted a two-step cluster analysis, as recommended by Hammett, Van Kleeck, & Huberty (2003). I first used the Ward hierarchical method to determine the most appropriate number of clusters. Although cluster analysis is designed to divide a sample into multiple homogeneous groups, determining the optimum number of clusters is a matter of subjective interpretation (Hammett et al., 2003). Visual analysis of the dendrogram suggests the presence of at least four clusters (see Appendix B). I examined the descriptive statistics for the four-cluster solution, and found that each cluster displayed a distinct, interpretable pattern of achievement and motivation, with the potential to provide implications for practice. I therefore considered these profiles theoretically meaningful and selected a fourcluster solution. Although the sample could have been partitioned still further, into a six- or nine-cluster solution, given the sample size of this study, the resulting clusters seemed too small to support meaningful interpretation. A disadvantage of the Ward hierarchical method of cluster analysis is that it makes only one pass through the data, and does not allow reassignment of students after additional clusters have been developed. Therefore, after establishing the number of clusters, I conducted a second analysis using the K-means iterative partitioning method, which more accurately assigns each unit to the most appropriate cluster. Next, I selected eight focus students for follow-up observations and interviews. I used NVivo to analyze student and teacher interviews using open coding, creating codes which were grounded in the data and allowing new themes regarding reading motivation to emerge (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 2011); for example, I noticed in students’ talk the emphasis they placed on knowing the right answer. Next, I used these codes to create focused codes, or more conceptual codes which described larger chunks of data—for instance, I combined codes knowing, not knowing, knowing procedure, not knowing as aspect of self, and redoing/second 13 Construct αc Construct SARA αc Subconstruct αc 0.7 Challenge 0.76 Academic Print 0.69 Efficacy 0.8 Self-Efficacy 0.76 Involvement 0.64 Academic Digital 0.67 Curiosity 0.8 Intrinsic Table 2. Internal Reliability of Constructs 0.88 0.56 Grades 0.85 0.68 Avoidance Recreational Digital 0.77 Competition 0.86 Extrinsic Recreational Print 0.75 Recognition MRQ 0.52 Compliance r=.57 Importance Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) 14 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read chance under the focused code knowing versus not knowing—and then recoded the interview data using these focused codes (Charmaz, 2010). Finally, I engaged in theoretical coding, seeking both confirming and disconfirming evidence of the theoretical propositions which motivated the selection of focus students (i.e., the dimensions of motivation and attitude discussed above) (Willig, 2013; Yin, 2014). I then applied these theoretical codes along with the focused codes generated from interview data, to my observation field notes. I also coded observation notes and interviews by focus student, so that I could easily identify all references to a particular student. Finally, I conducted cross-case analyses to seek patterns across clusters and schools. I began by creating a matrix for each cluster, pulling all the data on the two students within that cluster into a single document, with focused and theoretical codes listed across the top, and examples of those codes found in the data listed in individual rows. I analyzed each matrix, synthesizing patterns and noting contrasts between the two students, and wrote a memo describing each cluster. For example, I noted that both students in Cluster 2 named grades as their primary motivator for reading; however, I noticed a contrast in their levels of avoidance, with the student in School A showing a far clearer pattern of avoiding work than the School B student. Finally, I created a matrix for each school, pulling all the data on that school’s teacher and four students into a single document. I analyzed this document in a similar way, seeking patterns that crossed clusters, and thus could be related to school or classroom contexts, as well as contrasts among different students within the same context. Throughout the process, I wrote memos to document my analyses. Results Descriptives The two measures of academic achievement included in the study, the spring 2013 MCAS and fall 2013 IA, were not significantly correlated with one another overall (r = 0.21, p = 0.06). Due to this lack of correlation, the two variables could not be combined, so both were included in the analysis as separate measures of achievement. Neither MCAS nor IA scores differed significantly by school or gender; the average MCAS scores for both School A (239) and School B (248) fell into the “proficient” range. Caucasian students scored statistically significantly better than AfricanAmerican students on the MCAS (β = 15.86 points, p = 0.03). There were no differences among other racial groups in MCAS scores, and no difference among racial groups on IA scores. 15 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) Overall, reading motivation as measured by the MRQ was not correlated with students’ MCAS scores (r = 0.08, p = 0.56) and only moderately correlated with IA scores (r = 0.30, p = 0.01). As illustrated in Table 3, there were no significant differences in overall motivation, as measured by the MRQ, between students from different schools, of different genders, or of different races, although there were small statistically significant differences on some subscales. RQ1: Profiles of Reading Motivation and Achievement To address the first research question, Do distinct profiles of reading achievement and motivation exist for adolescents?, I conducted a cluster analysis indicating the existence of four theoretically meaningful profiles of reading motivation and achievement. As shown in Table 4, the distribution of race and gender in each cluster is relatively consistent with the distribution across the sample as a whole. 16 4 4 Mixed/ Other 5 Caucasian Asian 41 Female 14 27 Male Latino 52 School B 41 16 School A AfricanAmerican 68 Total Sample n 17 255.33 244.00 248.00 243.14 259.00 247.71 243.20 247.50 239.17 245.83 M 15.01 5.16 14.22 13.97 15.36 11.88 16.70 14.08 12.81 14.14 SD MCAS 64.25 73.75 74.93 68.61 79.00 70.49 71.07 70.54 71.31 70.72 M 18.71 8.06 12.72 12.39 12.39 13.55 14.90 15.48 7.79 14.00 SD Interim Assessment 138.75 131.50 151.71 139.78 140.60 140.17 144.15 139.88 147.81 141.75 M SD 45.59 22.75 15.80 22.93 14.88 23.51 22.00 23.31 20.79 22.84 MRQ 3.17 2.67 3.40 2.95 3.20 2.93 3.26 3.08 3.00 3.06 M 0.88 0.72 0.46 0.65 0.51 0.66 0.57 0.61 0.75 0.64 SD Self-efficacy 3.00 2.90 3.04 2.81 2.63 2.77 2.99 2.82 3.01 2.86 M 0.71 0.56 0.35 0.60 0.47 0.55 0.52 0.55 0.52 0.55 SD Intrinsic 2.93 2.43 2.99 2.73 2.78 2.75 2.83 2.71 3.01 2.78 M 0.69 0.71 0.53 0.60 0.44 0.56 0.62 0.60 0.49 0.58 SD Extrinsic 3.00 2.63 3.18 3.06 3.30 3.05 3.11 3.04 3.19 3.07 M 1.35 1.25 0.77 0.75 0.57 0.83 0.78 0.83 0.73 0.80 SD Importance Table 3. Means and Standard Deviations for Measures of Achievement, Motivation and Attitude 2.44 1.88 2.45 2.29 2.20 2.46 2.05 2.23 2.53 2.30 M 0.47 0.33 0.61 0.78 0.78 0.76 0.57 0.71 0.70 0.71 SD Avoidance 2.91 2.25 2.76 2.69 2.92 2.76 2.62 2.66 2.88 2.71 M 0.48 0.30 0.46 0.34 0.33 0.40 0.37 0.36 0.44 0.39 SD Compliance TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read 1.05 3.60 3.88 3.90 4.40 African-American Latino Asian Mixed/Other 3.78 3.72 Female Caucasian 1.22 3.69 3.66 School B Male 1.11 18 0.63 0.93 1.13 1.17 1.12 1.15 0.99 3.73 3.88 Total Sample SD School A M Academic Print 4.38 4.15 4.70 3.99 4.48 4.20 4.23 4.12 4.53 4.21 M 1.32 0.62 0.88 0.88 0.90 0.87 1.01 0.92 0.86 0.92 SD Academic Digital 3.35 3.95 4.16 3.64 3.68 4.04 3.30 3.75 3.75 3.75 M 1.58 1.30 1.31 1.41 1.15 1.22 1.46 1.42 1.17 1.36 SD Recreational Print 4.75 4.83 5.02 4.88 4.73 4.92 4.83 4.70 5.53 4.89 M 2.50 1.73 1.11 1.19 1.66 1.40 1.14 1.36 0.78 1.30 SD Recreational Digital Table 3. Means and Standard Deviations for Measures of Achievement, Motivation and Attitude (cont.) Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Table 4. Student Demographics by Cluster Cluster 1 Cluster 2 Cluster 3 Cluster 4 Total Male 0.42 0.5 0.46 0.22 0.42 Female 0.58 0.5 0.54 0.78 0.58 Caucasian 0.08 0.08 0 0.11 0.07 African-American 0.5 0.58 0.77 0.78 0.62 Latino 0.27 0.17 0.15 0.11 0.2 Asian 0.04 0.17 0.08 0 0.07 Mixed/Other 0.12 0 0 0 0.05 Cluster 1 (Average achievement, high motivation). As illustrated in Figure 1, cluster 1 (n = 26) demonstrated average achievement/high motivation. The group’s mean achievement level on both the MCAS and IA fell within the average range for the full sample, with 81% of the cluster scoring proficient or above on MCAS. Cluster 1’s mean scores were above average for intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, importance, and attitude toward academic reading (both print and digital). They fell within the average range in avoidance and compliance, as well as in their attitude toward recreational reading. Figure 1. Standardized achievement, motivation and attitude scores for Cluster 1: Average Achievement/High Motivation (n = 26) 19 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) While the cluster analysis suggests that students in this group are highly motivated across most dimensions of reading motivation and attitude, the cluster’s two focus students, Lily (School A) and Charles (School B), seemed most motivated by extrinsic factors. Both cited grades as the reason for the importance of reading; for example, Charles described a particular project as important “because I want to get a good grade on it. So I have to try my best on it.” Both differentiated between more and less important assignments based on the weight of the grade assigned to them; Lily said that “do nows,” or brief daily warmup assignments, are “just like not a lot of our grade, and it um, it’s like review from the last time. So we already discussed it. It’s not that important.” Despite the cluster’s above-average levels of selfefficacy, only Charles perceived himself as a good reader; Lily thought her skills were just average, based on her oral reading fluency. Although the group fell within the average range in compliance, both focus students seemed motivated by compliance in work completion. For instance, in all my observations, Lily followed instructions in class, and at one point stayed in her seat after the bell to finish a classwork assignment. However, on another occasion, when students were supposed to be revising an essay, she sat quietly, neatly recopying her essay word for word. When her teacher asked her, “Where are your edits?” she replied, “I don’t have any.” Thus, her behavior in class appeared to demonstrate compliance rather than intrinsic motivation. Both students admitted that they occasionally engage in unobtrusive avoidance behaviors; for example, Lily described a time when she “just stared around” instead of following along in the text. Charles, an avid recreational reader, reported reading about one book per week outside of school, but Lily said that she rarely reads recreationally. She recalled one instance where she read Diary of a Wimpy Kid (Kinney, 2007) because she was “really bored . . . I didn’t have nothing to do so I started walking around the house going like ‘uhhh’ and then I was like, uh I’ll just read a book what the heck.” However, she didn’t finish the book, and, laughing, admitted that “whenever I’m bored, I’ll start from the beginning again,” since so much time will have passed that she won’t be able to remember what she read. Cluster 2 (High achievement, average motivation). As shown in Figure 2, Cluster 2 (n=12) exhibited high achievement/average motivation. The group mean score for achievement was above average on both measures, with all but one student (92%) scoring proficient or advanced on MCAS; however, they fell within the average range on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, avoidance, compliance, and attitude toward all types of reading. This group reported below average beliefs about the importance of reading. 20 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Figure 2. Standardized achievement, motivation and attitude scores for Cluster 2: High Achievement/Average Motivation (n = 12) Despite this cluster’s low rating of the importance of reading on the MRQ, both focus students spoke persuasively about the importance of reading; Zoe (School A) said that all assignments in English are a 10 out of 10 in terms of importance. Kevin (School B) vividly described the desired behaviors of a good reader: “what I usually do is focus, listen to the teacher and like I write down what I’m supposed to do and when I get home I remember it and then I do it,” yet during my observations, he typically displayed off-task behaviors in class, walking around the room, socializing and teasing classmates. At one point, even when he appeared to be working quietly, he was actually carefully labeling boxes and drawing blank lines on which to write his answers, rather than engaging with substantive literacy work. In contrast, Zoe was generally compliant in class, participating frequently and completing all her classwork. I often observed her working ahead of the class—for example, she frequently did not follow along with the round robin reading, instead reading ahead and marking text on the next page. However, she reported that that she has “never read” a “motivating and fun” book. Thus, the responses of the two focus students in this cluster to survey and interview questions seemed to contradict the behaviors which I observed and which they describe. 21 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) Both students demonstrated high levels of extrinsic motivation (with grades as the primary motivator) and of self-efficacy. Kevin reported seeing himself as a good reader because he often knows the answer without looking back in the book. Zoe said that she thinks of herself as a strong reader because of her oral reading fluency and the speed at which she completes work. Neither student seemed to feel much agency around reading. Kevin indicated that the book is responsible for his engagement in reading (“I usually just get a random book that I see and it doesn’t really matter to me. . . . I don’t really like pay attention to what I’m reading. . . . I just look at the words and flip the pages randomly. But . . . when it’s like a good book that I like, I usually think it’s important”); his off-task behaviors are a result of other students distracting him, and the teacher is the source of surveillance responsible for forcing him to complete work. Zoe also attributed her choices about reading to extrinsic factors; for example, when describing a text she was unmotivated to read, she said, “after a while I realized that I’m gonna have to read the book if I wanted to get the grade. So I just read it.” Both students said that they sometimes read outside of school, but neither displayed an especially positive attitude toward recreational reading. Kevin identified examples of engaging with both academic print, saying he enjoyed A Long Way Gone, and with recreational print. Although Zoe said she occasionally reads Harry Potter books outside of school, she could not describe a single instance of being motivated to read or engaged with a text. Cluster 3 (Low achievement, low motivation). Cluster 3, illustrated in Figure 3, (n = 13) demonstrated low achievement/low motivation. This group scored below average on achievement measures (31% scored proficient on MCAS), as well as on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and compliance. However, they reported scores within the average range on importance, as well as average attitudes toward all types of reading. The teachers reported that the two focus students in this cluster lack skills and confidence. For example, Sarah said of Danny (School A), “I know that when he’s acting out behaviorally, it’s often because he has no idea what to do. That’s how I know he’s really lost if he takes apart part of his pencil and throws it at someone else.” Amanda acknowledged that Mariana (School B) struggles, but felt she has been helped immensely by a reading intervention this year with the school librarian. The students, however, presented a more mixed picture of self-efficacy. Both identified instances in which they felt like good readers, and engaged with texts, as well as incidences of struggle and disengagement. Danny said he feels like a good reader when finding evidence in text because “I read it already and I know where it is at.” Mariana described feeling like a good reader when “I know most of the meanings” of words in the text. Overall, 22 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Figure 3. Standardized achievement, motivation and attitude scores for Cluster 3: Low Achievement/Low Motivation (n = 13) their self-efficacy was relatively low; Danny said he is “not so much” a good reader because “I don’t read a lot,” and “I’m not fluent.” Mariana was unsure whether she is a good reader because “I don’t know my lexile and stuff.” She also admitted to lacking confidence: “I thought like I didn’t understand it but I think I understand it, but I just don’t, I just don’t have enough confidence to understand that I understand it.” Both students tended to blame the book, question or instructions for being “confusing” or “easy,” rather than internalizing their struggles and successes. According to Amanda, Mariana is compliant, and “always” completes her work. Avoidance seems clearly linked with self-efficacy for Mariana. In all of my observations, she diligently completed her assignments; however, she described to me a time when she didn’t finish an essay “’cause it was hard and I really didn’t want to do it ’cause it took too much work.” Danny, on the other hand, demonstrated little interest in being compliant. He told me matter-of-factly that “I don’t do homework much,” that the schoolwide behavior system “don’t mean nothing to me,” and that he doesn’t mind getting detention. He mentioned leaving class for bathroom breaks as one avoidance behavior, and I also observed him fidgeting, staring off 23 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) into space, and taking pencils apart. Danny didn’t link these avoidance behaviors with challenge; he told me he was enjoying the current wholeclass text, but disliked a previous one, Fahrenheit 451 (Bradbury, 2012), because “it was in the past, so then acting like it was in the future which made no sense…I didn’t understand the robots and stuff.” However, he said there is no difference in his behavior based on whether he is asked to read an engaging or disengaging text. Although neither Mariana nor Danny seemed to engage in much recreational reading of any kind, both expressed a preference for texts other than novels. Mariana said she likes to read magazine “articles about like if the countries are in poverty like the HDI and stuff, their life expectancy and literacy rate.” Danny reported enjoying graphic novels, and said he has a number of them at home, but he hasn’t read one since last year. Cluster 4 (Average achievement, low motivation). Depicted in Figure 4, Cluster 4 (n = 9) displayed average achievement/low motivation. This group scored within the average range on both achievement measures, with all but one student (89%) scoring proficient or advanced on MCAS, but reported below average scores on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, importance, and attitude toward academic reading, as well as scoring above average on avoidance. However, they scored within the average range on compliance and on attitude toward recreational reading (print and digital). Figure 4. Standardized achievement, motivation and attitude scores for Cluster 4: Average Achievement/Low Motivation (n = 9) 24 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read The two focus students in this cluster are the only two interviewed who seemed to base judgments about the importance of schoolwork on criteria other than grades. Dashawn (School B) explained that when given assignments like test preparation passages, which he feels are “not in my interest. . . . I just want to get it done. Like not try my best.” In my observations, Alesha (School A) typically didn’t track the text being read aloud with her pencil, as she was expected to do, and she explained: “I don’t think it’s necessary sometimes . . . [Sarah] says it helps us . . . but not necessarily because you’re basically going back and just underlining words.” Instead, she draws her own conclusions about importance, saying that she marks the text when something “sticks out to me.” For instance, Alesha made a note in her book at one point when Sarah modeled marking a specific example of foreshadowing. Additionally, both students reported experiencing involvement with texts: Dashawn said he has enjoyed reading A Long Way Gone (Beah, 2007) because it is “dramatic” and “crazy,” while Alesha said she dislikes Of Mice and Men (Steinbeck, 1937) because the treatment of Lennie “makes me sick inside.” Furthermore, the behavior of both Cluster 4 students seemed to belie the low motivation indicated by their survey results. In my observations, Dashawn was compliant in work completion, displaying an impressive ability to engage socially with peers while getting his work done at the same time. He told me that he likes to get work done ahead of deadline: “like pretend homework is like, you have two days to do it, I’ll just finish it right away so I won’t have to deal with it anymore.” During one observation, I saw him being reprimanded for trying to work faster than the rest of the class, and thus failing to follow instructions. However, he also reported a belief that effort is the key to success and that spending time on tasks is indicative of effort. He used the phrase “my best effort” over and over again, and spending time on his work, “extra long,” seemed to be the way he measured whether he had applied his “best effort.” Dashawn also described engaging enthusiastically in recreational reading at least sometimes; specifically, he bragged that when he got the new Diary of a Wimpy Kid book, he “read it in the first day.” Thus, Dashawn’s talk and behavior seemed to contradict the survey results which placed him in this cluster— perhaps he felt that the survey was “not in his interest,” and rushed to get it done rather than supplying thoughtful answers. Alesha declared several times over the course of our interview, “I don’t like reading.” She reported struggling with the reading tasks expected of her, and internalized the struggle with comments like, “I’m not that good at symbolism.” She described avoiding tasks when she believes she doesn’t know the answer, even going so far as to miss a day of school. Yet in the past, Alesha has been an avid recreational reader. She immigrated 25 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) to the United States from Jamaica less than two years ago, and told me that “when I was in Jamaica . . . I used to read so much books, it wasn’t even funny.” She described several books with which she deeply engaged, because she found them “inspiring.” She wasn’t sure what had changed, but offered three possible reasons: first, access to books. In Jamaica, she borrowed books from her aunt’s office; in the United States she wasn’t sure where to obtain books she might enjoy reading. Second, distraction: in Jamaica, she lived with only her aunt, whereas in the United States, she lives with “so much sisters.” Finally, like the other students at School A, she equated reading with reading aloud, and explained: I have a very very strong accent so like when I read . . . I get very nervous cause I just don’t like reading because I like think that when I like say my accent people don’t understand what I say so I might be very scared. So I’m like very shy sometimes. . . . I think a girl got suspended for like making fun of my accent and I was crying that day because, I don’t know. It was my first year at school and I was- it was horrible . . . like that’s why I don’t like reading honestly because my accent too. I don’t really like to read because when I read people like laugh at me. I don’t really like to read honestly. So that’s kinda like the motivation not to read. Conclusions. This analysis suggests that four distinct reading motivation/achievement profiles may exist among adolescent readers in diverse low-income public schools, and that the relationships between reading achievement and motivation are more complex than the correlations described in previous research. Particularly surprising, and worthy of further exploration, is the finding that students with low motivation may demonstrate average, rather than low, levels of achievement. However, in addition to variability across clusters, qualitative analysis indicates that significant variability exists both within clusters (e.g., Cluster 1’s overall average attitude toward recreational reading obscures the contrast between Lily’s and Charles’ reading habits) and within individual students (e.g., the difference between Alesha’s reading behaviors in Jamaica and the United States, the difference between the way Kevin talked about reading and the way he behaved toward it). This underscores the importance of the mixed-methods approach of this study, as either a quantitative or qualitative analysis alone would have missed these important, seemingly contradictory findings. Therefore, in the next section, I will expand on the findings described above, using the study’s qualitative data to examine contextual factors which may be related to students’ reading motivation. 26 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read RQ2: Reading Motivation Levers: Reports from Teachers and Students To address the second research question, What are the key levers to fostering motivation to read in adolescents? To what extent does the relative salience of these levers vary systematically according to achievement/motivation profiles?, I conducted cross-case analysis within each cluster and within each school to explore school-, teacher-, and classroom-level factors which could be key levers in promoting or detracting from students’ motivation to read. First, as in other research where students value what teachers convey is important (Wilson, Martens, & Arya, 2005), all eight focus students described feeling successful when they knew the correct answer to the teacher’s questions, particularly when they could get the answer quickly and without much effort. For example, Kevin described a specific assignment which made him feel like a good reader because “I knew everything and I didn’t really have to look back in the book that much.” In all the direct instruction I observed, both teachers followed a traditional Initiate-Respond-Evaluate pattern of classroom discourse (Cazden & Beck, 2003), and always seemed to have a correct answer in mind. For example, in the following excerpt from my field notes: “Amanda asks how many opportunities for descriptive writing they will have. The students wildly guess numbers. The correct answer is seven (I don’t know why).” Teachers in both classrooms responded to students’ answers with a brief: “No,” or “Exactly,” or occasionally, “Almost. You’re dancing with the correct answer.” Yet both teachers emphasized their desire for students to participate more. In her interview, Amanda said: “participation in general is more important to me than being right. So I like students to take risks and I like them to feel like it’s okay to be wrong.” In class, Sarah encouraged students more than once: “I want more participation. Don’t be afraid to guess,” and in her interview, she described students who “see themselves as scholars” being “brave enough to say it and get it wrong, who cares.” Although both teachers reported believing philosophically in encouraging students to take risks, in my observations, both were brusque in acknowledging correct or incorrect answers, and more importantly, they did not acknowledge that some questions, particularly in literary analysis, have more than one possible right answer. This instructional practice seemed to be reflected in students’ statements about the importance of getting the right answer, and their apparent belief in their ability to get this answer as a sign of their cognitive ability. Furthermore, given the emphasis on round robin “interactive” reading in School A, all four School A students defined their own success as readers based on their oral reading fluency. In Danny’s words, being a good reader means “reading it without, you know, stopping all the time. And reading at the punctuation marks.” Lily described herself as a reader “like 27 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) average students this age would be. Like not too slow and not too fast,” while Zoe said that she is a good reader because “I try not to mess up on words so much.” In Alesha’s case, this emphasis on oral reading fluency seems to have turned her against reading entirely. Secondly, despite the critical role of reading amount in promoting achievement (Guthrie & McRae, 2012; Guthrie, Wigfield, Metsala, et al., 2004; Schaffner et al., 2013), neither teacher tracks whether students read outside of class. When I asked the teachers in interviews whether specific students read recreationally, they responded “Um, I don’t know the answer to that,” or, “I can’t say, but I don’t think so.” When probed, the teachers offered guesses about whether students read recreationally based on their achievement in school. For example, Amanda said that she thinks Kevin reads outside of school “just based on the thoroughness of his answers and the level of comprehension that I see, and [his] confidence in sort of engaging with texts.” When asked if Deshawn reads recreationally, she replied, “I don’t know this for a fact, [but] I am tempted to think yes based on how he engages with text, and that’s something that only comes with exposure.” In contrast, she said that Mariana “doesn’t strike me as an avid reader,” and that Charles probably doesn’t read recreationally, except maybe graphic novels. Actually, all four School B students reported reading outside of school sometimes, and Charles reported the most avid reading of all interviewed students. Sarah insisted that School A students don’t have much time to read recreationally, because of their workload, but guessed that Zoe probably reads outside of school because “with the way that she, like, uses inflection in her voice when she reads fluently and whatnot, . . . it’s clear that in the past she has and that it’s not a bizarre thing for her to be reading,” and that Lily probably reads recreationally because “she last year used to come in with free reading books every once in a while. She doesn’t as much this year.” Although all focus students from School A said they read outside of school occasionally, none reported engaging in regular recreational reading. Both teachers said that they teach some students (although none whom I interviewed) who “walk around with their own personal books . . . who just have this love of reading and will read at any point if they can.” At School B, students have one period per week of independent reading time and a flourishing school library—three of the four students from School B mentioned the librarian as a source for helping them select engaging books. As in other contexts which promote students’ extensive independent reading (Francois, 2013), Amanda told me that she frequently engages in leisure reading of young adult novels. All four focus students in School B, despite their varying levels of motivation, reported more reading outside of school than any student interviewed from School A. The 28 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read amount of recreational reading School B students reported varies according to level of motivation—Charles reads much more than Mariana—but even Mariana, according to her interview, reads more than any School A student. This pattern suggests that, consistent with the literature (Francois, 2013; Ivey & Broaddus, 2001; Ivey & Johnston, 2013; Kirkland, 2011; Moje et al., 2008), these contextual factors (e.g., class time for independent reading, access to high-interest texts, adult support in text selection) may play a role in promoting students’ motivation to read. Third, teachers’ beliefs about which students were motivated and successful did not always align with survey results or students’ perceptions of themselves. The two teachers described Zoe, Mariana, and Dashawn as intrinsically motivated, based largely on their compliant behavior. For example, Amanda said she knows Mariana is intrinsically motivated because “she just does what you ask her to do and there’s never any pushback.” According to survey results, my observations and their selfreports, these three students demonstrated the highest level of compliance in work completion, but were not necessarily motivated to read by curiosity or involvement with texts. The teachers seemed to use participation in class as an indicator of motivation. Sarah said that Zoe is “self-motivated” because “she always wants to participate,” while Amanda reported that Kevin and Dashawn are confident and motivated because they are “really participatory.” They viewed the other students as less motivated because they participated less. Although Charles, according to his survey and interview results, is a highly motivated and avid reader, Amanda didn’t see him this way. She acknowledged that “his grades in general are okay, I mean he’s often in the 80s,” but “I just think the affect in class tends to read that it feels challenging or that he’s not super confident.” Thus, even Charles’ demonstrated ability to achieve good grades did not outweigh his lack of participation in Amanda’s estimation of his comprehension and motivation. Therefore, it seemed that the two teachers focused on behavioral engagement, indexed by compliance in work completion and participation in class, to identify which focus students they believed were intrinsically motivated. Finally, both teachers cited engaging text choices as key factors in motivating students to read, but they used different criteria in selecting texts for students. The teachers, in collaboration with colleagues, had substantial leeway in choosing texts to assign. Both mentioned difficulty level as well as interest level; however, where Amanda said she seeks texts which are “accessible, but not too easy and definitely not out of reach to the point where it’s challenging and turns kids off to reading,” Sarah said she chooses “grade level and then above grade level texts.” Amanda’s selections consisted mostly of high-interest young adult novels, such as Make Lemonade 29 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) (Wolff, 2006) and Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (Alexie, 2009). She said, “I am always really sad . . . that we don’t do the classics in middle school. . . . There are so many books that I wish we taught and probably aren’t a good fit for our kids.” At School A, students read “classics” almost exclusively; I observed them reading Of Mice and Men (Steinbeck, 1937) and Lord of the Flies (Golding, 1955). Sarah explained that she chose these texts because they “are sort of classics that they probably will see again in high school, so it’s kinda nice for our kids to have had a touch with them already. . . . It just gives them sort of at bats with these classic novels.” She further explained that: you don’t have to understand every single thing to get the gist of what’s happening, and I think Alesha and Danny and some other kids are just, they hear these phrases and whatnot, and it’s hard to move past the fact that whoa, that I have no idea what she’s talking about there or what Golding’s talking about there and so now I’m totally lost, as opposed to other kids who will just be like, oh I don’t get it but I get this, okay this is now what’s happening. Interestingly, I didn’t observe a vast difference in students’ perceptions of the two types of texts, as all four students from School B and three of the four from School A described specific instances of being engaged with assigned texts. Discussion This study was designed to produce a description of adolescent reading motivation and achievement that is more generalizable than isolated case studies, while providing a more nuanced picture than would be possible through survey research alone. Findings suggest that four distinct reading motivation and achievement profiles may exist among a diverse group of adolescents. This study presents several interesting contrasts with previous research, as well as providing important implications for practice. In particular, the present study suggests that teachers could benefit from gathering more information about students’ reading motivation, beyond observations of work completion and class participation—and that teachers should continue to gather such information over the course of days and weeks, paying close attention to the contexts within which students are motivated to read, rather than relying on a single static measure. While recognizing the pressures middle school teachers face with limited time and many students, gathering information about students’ motivation through self-report in brief informal conversations would be invaluable. This might help teachers tap into the unrealized potential of students like Kevin, who 30 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read spoke so eloquently about the importance of reading but didn’t enact it; like Zoe, who completed all assigned work without truly engaging with text; and certainly of students like Charles and Alesha, whose current or former avid recreational reading went unrecognized and unrewarded. Survey data from this study suggests several interesting contrasts with previous research on adolescent reading motivation. First, reading motivation as measured by the MRQ is not correlated with students’ state standardized test scores as might be expected. This result has been found in other research (e.g., Guthrie, Wigfield, & Humenick, 2006; Neugebauer, 2014), and may reflect the disadvantage of using a context-general measure which treats reading motivation as stable. Alternatively, it may reflect the relatively shallow level of comprehension measured by the MCAS, on which highly skilled students can perform adequately even when they are not highly motivated (Neugebauer, 2014). Finally, the relationship between reading motivation and achievement is complex and indirect, often mediated through reading amount, which was not measured in this study (Guthrie & McRae, 2012; Guthrie, Wigfield, Metsala, et al., 2004; Schaffner et al., 2013). This finding underscores the importance of going beyond quantitative analysis to explore the multifaceted relations among context, motivation and achievement. Secondly, previous research suggests that on average, girls are more motivated to read than boys (Baker & Wigfield, 1999; Mucherah & Yoder, 2008; Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997). Compared to Baker and Wigfield’s (1999) study of fifth and sixth graders, the girls in the present study scored lower on all dimensions of motivation except avoidance; however, the boys in this sample scored similarly on intrinsic motivation and importance, the same or slightly higher in self-efficacy, and lower in compliance, avoidance, and some aspects of extrinsic motivation (grades and recognition). Thus, the absence of a gender gap in the present study resulted from the girls being less motivated than girls in previous research, rather than the boys being more motivated. Recent research suggests that while the gap between African-American males and other race and gender groups exists in middle-income samples, low-income African-American females are, on average, no more motivated than low-income African-American males (Guthrie & McRae, 2012). Therefore, while this finding could be explained by the small sample size in this study, it also could have occurred because this sample was drawn from a low-income population consisting predominantly of students of color. Finally, although this sample’s mean attitude toward recreational digital reading was not significantly different from the seventh graders in McKenna and colleagues’ original study (McKenna et al., 2012), and attitude toward recreational digital reading was not a distinguishing factor among clusters, in interviews only two focus students (Lily and Dashawn) 31 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) reported sometimes reading friends’ Facebook statuses, and only one (Alesha) said she engages in more extended digital reading, reading news about celebrities and occasionally researching topics of interest on Wikipedia. The other students said they never access text digitally, and neither teacher reported using digital text in class. This stands in contrast to much recent research which has emphasized that despite middle school students’ general lack of reading motivation in school, they often engage in frequent and highly motivated reading of digital texts outside of school (e.g., Alvermann & Heron, 2001; Moje et al., 2008). Motivation/Achievement Profiles Cluster analysis suggests that four distinct reading motivation and achievement profiles exist, and that key levers for promoting reading motivation may differ according to students’ achievement/motivational profiles. Brophy’s (1998) concept of optimal matching, described as “a motivational analog of the ‘zone of proximal development,’” (p. 258) may be instrumental in considering how to best match motivational strategies to students’ needs. Brophy suggests that in an optimal learning environment, students would perceive the self-relevance of material, and appreciate that there are good reasons to learn this material. However, the way in which teachers build self-relevance and appreciation may look different for different students. For instance, students in Clusters 1 (average achievement/high motivation), 2 (high achievement/average motivation), and 3 (low achievement/low motivation), despite their varying levels of achievement and motivation, all demonstrate high levels of extrinsic motivation, with grades as the primary motivating factor. All six focus students in these clusters articulated an orientation toward performance goals, with an emphasis on demonstrating competence (by earning a good grade) rather than increasing competence (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). This was often associated with a belief in an inverse relationship between effort and intelligence as all six reported feeling successful when they could achieve correct answers quickly and with minimal work. This is concerning given that current research suggests that intrinsic motivation may be more beneficial to achievement than extrinsic motivation (Becker et al., 2010; McGeown et al., 2012; Schaffner et al., 2013). Thus, students in Clusters 1 and 2 could benefit from teachers’ modeling, coaching, and scaffolding in appreciation in order to build their belief in the value and importance of reading, above and beyond earning good grades (Brophy, 1998). For instance, teachers might introduce learning activities in engaging ways which convey their purpose, model curiosity and interest 32 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read in their subject matter, provide constructive feedback, and convey the expectation that students behave as engaged learners (Brophy, 1998). Furthermore, Cluster 2 students might be provided with more challenging work since they are able to succeed academically without authentic engagement with texts. While students in Cluster 3 could also benefit from the appreciationbuilding activities described above, their generally low self-efficacy must also be addressed. Teachers should minimize performance anxiety by promoting the beliefs that intelligence is incremental, and that effort leads to success (Brophy, 1998; Dweck & Leggett, 1988). Importantly, teachers should also recognize that these students do sometimes experience feelings of success in reading, and teachers should reinforce these occasions with positive feedback. Finally, students in Cluster 4 (average achievement/low motivation) may benefit from understanding the self-relevance of learning opportunities. Since these students tend to choose whether or not to complete tasks based on their personal beliefs about the tasks’ importance, rather than external factors like grades, it is critical that they understand how each learning opportunity relates to their personal goals (Brophy, 1998). However, the variation in reading motivation within individual students (e.g., the difference between Alesha’s reading behaviors in Jamaica and the United States, and the difference between the way Kevin talks about reading and the way he behaves toward it) is so great that the implications of these profiles may be difficult to implement in practice. Recent research suggests that 31% of variation in reading motivation scores is due to “daily within-student fluctuations” (Neugebauer, 2014, p. 171). Thus, teachers should recognize that students’ apparent motivation or lack thereof is likely highly dependent on context. Rather than assuming that some students (like Zoe or Mariana) are highly motivated, while others (like Charles or Alesha) are less so, teachers could benefit from gathering information about the contexts within which particular students are motivated or unmotivated, and working to adapt their instruction accordingly. This within-student variability may further explain the surprising finding, in contrast to prior research, that students may be average or high achievers without correspondingly high levels of motivation. Most previous research has relied on either self-report via survey and interview (e.g., Baker & Wigfield, 1999; Ivey & Broaddus, 2001) or classroom observation (e.g., Raphael, Pressley, & Mohan, 2008), which would lead researchers as well as practitioners to be unaware of the inconsistencies in seventh graders’ presentations of reading motivation. 33 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) READING MOTIVATION LEVERS Self-determination theory suggests that intrinsic motivation may be promoted through building autonomy, competence and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Interview and observation data suggest that the two teachers in this study are aware of, and trying to implement, some but not all of these three key levers. Both teachers recognized the importance of relatedness. Amanda said that she tries to achieve this through choosing texts about engaging topics like teen pregnancy and through frequent group work. Despite Sarah’s choice of classics, she believed that “the themes were exciting enough that it would keep them invested.” However, neither teacher discussed the importance of her own relationship with her students, despite evidence that this may be the factor most strongly associated with intrinsic motivation (De Naeghel et al., 2014). Both teachers spoke about the importance of feeling competent, and about trying to instill these feelings in their students—for example, Sarah said she prompts struggling students before calling on them to be sure they aren’t “lost in the text” and that their answers are “somewhere in the ballpark”—but in practice, both teachers’ brusque acknowledgment of right and wrong answers may detract from students’ competence beliefs. One motivational lever largely unobserved in either classroom is autonomy. Although School B students did have some choice in the texts they read during their weekly reading workshop, they were provided with little support in exercising this autonomy. Amanda did not appear to “deliberately attempt to identify what is relevant for students” and recommend books accordingly (Ivey & Johnston, 2013, p. 272). Francois (2013) suggests that schedules and resources alone cannot create a reading culture, but are merely the structures which allow engagement with literacy to occur. This lack of autonomy support may explain why the greater amount of recreational reading reported by students at School B as compared to School A is not associated with higher average levels of motivation to read. At both schools, students reported feeling very little agency regarding reading. In interviews, students tended to blame the text, question or instructions for being easy or confusing (“That book was, it was longer. And it was like confusing; even the librarian told me it was confusing”); they tended to hold texts responsible for being engaging or disengaging (“I just didn’t like it; it was stupid”); they tended to name grades as the factor which forced them to read (“they usually are really important, because the assignments she gives us are like big parts of our grade”); and they tended to hold the teacher responsible for determining whether they had achieved the right or wrong answer. Some research has found an association between teachers’ autonomy support 34 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read and students’ intrinsic motivation for girls, but not for boys (De Naeghel et al., 2014). This is especially relevant given the fact that the girls in this sample were less motivated, on average, than girls in other research, while the boys reported about the same levels of motivation. Thus, the lack of autonomy support provided by Amanda and Sarah might be especially detrimental to their female students. Implications for Practice Seventh graders’ increasing desire for autonomy may productively be met by allowing choice in some aspects of task, time, technique and team: in other words, in the tasks they pursue, along with how, when and with whom those tasks are accomplished (Eccles & Roeser, 2011; Pink, 2009). Ideally, teachers might expand students’ ability to self-select texts, and provide them with support in choosing texts which are relevant and in using talk about those texts to engage with peers and adults (Francois, 2013; Ivey & Broaddus, 2001; Ivey & Johnston, 2013; Kirkland, 2011; Moje et al., 2008). However, even if schools and teachers are not willing or able to make a major overhaul of their curricula, one important area where students may begin to experience autonomy is in interpretation of texts; teachers could work to convey that there is more than one correct answer to many questions of literary analysis. By encouraging effort more than rewarding students who achieve the right answer, teachers may build students’ motivation through increasing their self-efficacy. Additionally, teachers should be aware of the influence of their own relationships with students. Middle school teachers who face large numbers of students and increasing pressure to cover content may not recognize the importance of time spent building relationships, and the relevance of these relationships to students’ motivation and achievement. Finally, teachers could benefit from the understanding that their students’ motivation may vary in different contexts and could work to understand which contexts motivate which particular students (Neugebauer, 2014). Since supporting students’ intrinsic motivation is an important goal, teachers should look beyond obvious indicators of behavioral engagement such as class participation and compliance in work completion to discover which contexts foster true involvement and curiosity for individual students. LIMITATIONS First and most importantly, there is significant debate about the reliability and validity of the MRQ; Watkins and Coffey (2004) and Bozack (2011) were unable to replicate the MRQ’s dimensions of reading motivation using confirmatory factor analysis with three different samples. To combat 35 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) this, I confined my analysis to the nine factors contributing to reading motivation which were theoretically justified by Schiefele and colleagues (2012), rather than the full eleven measured by the MRQ, as well as using qualitative measures to further develop my understanding of students’ reading motivation. Secondly, the schools, teachers, and students were not randomly selected for participation. Schools were recruited through personal contacts, and teachers and students were chosen for scheduling reasons. Furthermore, since students had to return a signed permission slip in order to participate, those with the lowest levels of academic motivation may have self-selected out of the study. This, combined with the small sample size, means that these results may not generalize to other populations. Third, the MRQ focuses primarily on fiction reading, asking students to agree or disagree with statements like, “I feel like I make friends with people in good books”; in addition, I only observed students reading fiction in class. Some research suggests that dimensions of reading motivation may play out differently for informational texts (Ho & Guthrie, 2013); given recent increased emphasis on nonfiction reading (Common Core State Standards, 2010), this is an important area for future research. Despite these limitations, it is worth investing time in determining which factors promote reading motivation for particular groups of students, since motivation to read is a strong predictor of students’ reading achievement. While the students in this study demonstrated complex and variable motivations to read, which may not be captured on a single, static survey measure, they also demonstrated responsiveness to teachers’ (often implicit) beliefs about what is important. This suggests that teachers have substantial influence over adolescent student populations. By encouraging their students’ feelings of competence in reading, by building personal relationships with students as well as providing them with engaging, relatable texts, and by allowing students some autonomy in the texts they read and tasks they engage in, teachers may be able to increase reading motivation in middle school students. 36 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read References Alexie, S. (2009). The absolutely true diary of a part-time Indian (1st paperback ed.). New York: Little, Brown and Company Alvermann, D. E. (2001). Reading adolescents’ reading identities: Looking back to see ahead. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 44(8), 676–690. Alvermann, D. E., & Heron, A. H. (2001). Literacy identity work: Playing to learn with popular media. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45(2), 118–122. Baker, L., Dreher, M. J., & Guthrie, J. T. (2000). Engaging young readers: Promoting achievement and motivation. Solving problems in the teaching of literacy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Baker, L., & Wigfield, A. (1999). Dimensions of children’s motivation for reading and their relations to reading activity and reading achievement. Reading Research Quarterly, 34(4), 452–477. doi:10.1598/rrq.34.4.4 Beah, I. (2007). A long way gone: Memoirs of a boy soldier (1st ed.). New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Becker, M., McElvany, N., & Kortenbruck, M. (2010). Intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation as predictors of reading literacy: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 773–785. doi:10.1037/a0020084 Boyne, J. (2006). The boy in the striped pajamas : A fable (1st American ed.). New York: David Fickling Books. Bozack, A. (2011). Reading between the lines: Motives, beliefs, and achievement in adolescent boys. High School Journal, 94(2), 58–76. Bradbury, R. (2012). Fahrenheit 451 (1st Simon & Schuster trade paperback ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. Brophy, J. E. (1998). Motivating students to learn. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. Bundick, M. J., Quaglia, R. J., Corso, M. J., & Haywood, D. E. (2014). Promoting student engagement in the classroom. Teachers College Record, 116(4), 1–34. Cazden, C. B., & Beck, S. (2003). Classroom discourse. In A. C. Graesser, M. A. Gernsbacher, & S. R. Goldman (Eds.), Handbook of discourse processes (pp. viii). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Charmaz, K. (2010). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In W. Luttrell (Ed.), Qualitative educational research: Readings in reflexive methodology and transformative practice (pp. xi). New York, NY: Routledge. Common Core State Standards, I. (2010). Common core state standards for English language arts & literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Retrieved from http://ezpprod1.hul.harvard.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=tru e&db=eric&AN=ED522008&site=ehost-live&scope=site and http://www.corestandards. org/assets/CCSSI_ELA%20Standards.pdf Conradi, K., Jang, B. G., Bryant, C., Craft, A., & McKenna, M. C. (2013). Measuring adolescents’ attitudes toward reading: A classroom survey. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56(7), 565–576. doi:10.1002/jaal.183 De Naeghel, J., Valcke, M., Meyer, I., Warlop, N., Braak, J., & Keer, H. (2014). The role of teacher behavior in adolescents’ intrinsic reading motivation. Reading & Writing, 27(9), 1547–1565. doi:10.1007/s11145-014-9506-3 Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum. Dressman, M., Wilder, P., & Connor, J. J. (2005). Theories of failure and the failure of theories: A cognitive/sociocultural/macrostructural study of eight struggling students. Research in the Teaching of English, 40(1), 8–61. 37 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256 Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values and academic behaviors In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and sociological approaches. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman. Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence (Wiley-Blackwell), 21(1), 225–241. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Francois, C. (2013). Reading in the crawl space: A study of an urban school’s literacy-focused community of practice. Teachers College Record, 115(5), 1–35. Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. doi:10.3102/00346543074001059 Froiland, J. M., & Oros, E. (2014). Intrinsic motivation, perceived competence and classroom engagement as longitudinal predictors of adolescent reading achievement. Educational Psychology, 34(2), 119–132. doi:10.1080/01443410.2013.822964 Golding, W. (1955). Lord of the flies, a novel ([1st American] ed.). New York, NY: Coward-McCann. Guthrie, J. T., Coddington, C. S., & Wigfield, A. (2009). Profiles of reading motivation among African American and Caucasian students. Journal of Literacy Research, 41(3), 317–353. doi:10.1080/10862960903129196 Guthrie, J. T., Klauda, S. L., & Ho, A. N. (2013). Modeling the relationships among reading instruction, motivation, engagement, and achievement for adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(1), 9–26. Guthrie, J. T., & McRae, A. (2012). Motivations and contexts for literacy engagement of African American and European American adolescents. In J. T. Guthrie, A. Wigfield, & S. L. Klauda (Eds.), Adolescents’ engagement in academic literacy. Retrieved from http://www. corilearning.com/research-publications Guthrie, J. T., Schafer, W. D., & Huang, C.-w. (2001). Benefits of opportunity to read and balanced instruction on the NAEP. Journal of Educational Research, 94(3), 145–162. doi:10.1080/00220670109599912 Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. In P. D. Pearson, R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, & P. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 3, pp. 403–422). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & Humenick, N. M. (2006). Influences of stimulating tasks on reading motivation and comprehension. I(4), 232–245. doi:10.3200/joer.99.4.232-246 Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Metsala, J. L., & Cox, K. E. (2004). Motivational and cognitive predictors of text comprehension and reading amount. In R. B. Ruddell & N. J. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading. Fifth edition. (pp. 929–953). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & Perencevich, K. C. (2004). Motivating reading comprehension: Concept-oriented reading instruction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Hammett, L. A., Van Kleeck, A., & Huberty, C. J. (2003). Patterns of parents’ extratextual interactions during book sharing with preshool children: A cluster analysis study. Reading Research Quarterly 38(4), 442–468. Ho, A. N., & Guthrie, J. T. (2013). Patterns of association among multiple motivations and aspects of achievement in reading. Reading Psychology, 2, 101–147. doi:10.1080/0270271 1.2011.596255 38 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Ivey, G. (1999). A multicase study in the middle school: Complexities among young adolescent readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 34(2), 172–192. Ivey, G., & Broaddus, K. (2001). “Just plain reading”: A survey of what makes students want to read in middle school classrooms. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(4), 350–377. Ivey, G., & Johnston, P. H. (2013). Engagement with young adult literature: Outcomes and processes. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(3), 255–275. doi:10.1002/rrq.46 Jacobs, J. E., Lanza, S., Osgood, D. W., Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Changes in children’s self-competence and values: Gender and domain differences across grades one through twelve. Child Development, 73(2), 509–527. Kelley, M. J., & Decker, E. O. (2009). The current state of motivation to read among middle school students. Reading Psychology, 30(5), 466–485. doi:10.1080/02702710902733535 Kinney, J. (2007). Diary of a wimpy kid: Greg Heffley’s journal. New York, NY: Amulet Books. Kirkland, D. E. (2011). Books like clothes: Engaging young black men with reading. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 55(3), 199–208. doi:10.1002/jaal.00025 Klauda, S., & Guthrie, J. (2015). Comparing relations of motivation, engagement, and achievement among struggling and advanced adolescent readers. Reading and Writing, 28(2), 239–269. doi:10.1007/s11145-014-9523-2 Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. Legault, L., Green-Demers, I., & Pelletier, L. (2006). Why do high school students lack motivation in the classroom? Toward an understanding of academic amotivation and the role of social support. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(3), 567–582. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.3.567 Lesaux, N. K., & Kieffer, M. J. (2010). Exploring sources of reading comprehension difficulties among language minority learners and their classmates in early adolescence. American Educational Research Journal, 47(3), 596–632. McGeown, S. P., Norgate, R., & Warhurst, A. (2012). Exploring intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation among very good and very poor readers. Educational Research, 54(3), 309–322. McKenna, M. C., Conradi, K., Lawrence, C., Jang, B. G., & Meyer, J. P. (2012). Reading attitudes of middle school students: Results of a U.S. survey. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(3), 283–306. doi:10.1002/rrq.021 Moje, E. B., Overby, M., Tysvaer, N., & Morris, K. (2008). The complex world of adolescent literacy: Myths, motivations, and mysteries. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 107–154. Mucherah, W., & Yoder, A. (2008). Motivation for reading and middle school students’ performance on standardized testing in reading. Reading Psychology, 29(3), 214–235. National Center for Education. (2015). The nation’s report card: Mathematics and reading assessments. Washington, DC: National Center for Education. Neugebauer, S. R. (2014). Context-specific motivations to read for adolescent struggling readers: Does the motivation for reading questionnaire tell the full story? Reading Psychology, 35(2), 160–194. doi:10.1080/02702711.2012.679171 Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. New York, NY: Riverhead Books. Raphael, L. M., Pressley, M., & Mohan, L. (2008). Engaging instruction in middle school classrooms: An observational study of nine teachers. Elementary School Journal, 109(1), 61–81. Reardon, S. F., Valentino, R. A., & Shores, K. A. (2012). Patterns of literacy among U.S. students. Future of Children, 22(2), 17–37. Retelsdorf, J., Köller, O., & Möller, J. (2014). Reading achievement and reading self-concept— Testing the reciprocal effects model. Learning & Instruction, 29, 21–30. doi:10.1016/j. learninstruc.2013.07.004 39 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. doi:10.1006/ ceps.1999.1020 Schaffner, E., Schiefele, U., & Ulferts, H. (2013). Reading amount as a mediator of the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation on reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(4), 369–385. doi:10.1002/rrq.52 Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., & Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(4), 427–463. doi:10.1002/rrq.030 Solheim, O. J. (2011). The impact of reading self-efficacy and task value on reading comprehension scores in different item formats. Reading Psychology, 1, 1–27. doi:10.1080/02702710903256601 Steinbeck, J. (1937). Of mice and men. New York, NY: Collier. Taboada, A., Tonks, S. M., Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (2009). Effects of motivational and cognitive variables on reading comprehension. Reading & Writing, 22(1), 85–106. doi:10.1007/s11145-008-9133-y Watkins, M. W., & Coffey, D. Y. (2004). Reading motivation: Multidimensional and indeterminate. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(1), 110–118. Wigfield, A. (2000). Facilitating children’s reading motivation. In L. Baker, M. J. Dreher, & J. T. Guthrie (Eds.), Engaging young readers: Promoting achievement and motivation. Solving problems in the teaching of literacy. New York, NY: Guilford Publications Inc. Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of children’s motivation for reading to the amount and breadth of their reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 420–432. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.420 Willig, C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology (3rd ed.). Maidenhead, UK: McGraw Hill Education, Open University Press. Wilson, P., Martens, P., & Arya, P. (2005). Accountability for reading and readers: What the numbers don’t tell. The Reading Teacher, 58(7), 622–631. doi:10.2307/20204285 Wolff, V. E. (1993). Make lemonade. Harrisonburg, VA: Square Fish. Wolters, C., Denton, C., York, M., & Francis, D. (2014). Adolescents’ motivation for reading: Group differences and relation to standardized achievement. Reading & Writing, 27(3), 503–533. doi:10.1007/s11145-013-9454-3 Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE. 40 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Appendix A School Site Demographics School A School B Race/ethnicity African-American: 53.2% Hispanic: 42.1% Caucasian: 1.5% Asian: 0.5% Multi-race: 1.6% African-American: 56.6% Hispanic: 19.9% Caucasian: 13.4% Asian: 6.7% Multi-race: 3.1% Low income 71% 63% MCAS Scores–% proficient and above 2012 – 65% 2011 – 78% 2010 – 77% 2009 – 82% 2008 – 83% 2012 – 80% 2011 – 78% 2010 – 84% 2009 – 89% 2008 – 74% 41 42 0 L2squared dissimilarity measure 100 200 300 400 1 7 13 22 15 8 2 53 10 23 52 3 4 14 20 11 17 18 5 12 16 19 54 6 46 9 21 24 25 26 27 28 37 29 39 42 30 38 34 40 33 51 47 43 44 48 31 32 35 55 36 41 45 49 50 56 59 57 58 60 Dendrogram for Ward’s Cluster Analysis, Indicating Existence of Four Clusters Appendix B Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Appendix C Psychometrics for Survey Measures Table C1: Results of Reliability Analysis for Survey Measures n Sign item-test corr. item-rest corr. interitem cov. alpha Q7: I know that I will do well in reading next year. 68 + 0.82 0.56 0.24 0.51 Q15: I am a good reader. 68 + 0.78 0.52 0.28 0.58 Q21: I learn more from reading than most students in the class. 67 + 0.78 0.44 0.33 0.71 0.29 0.69 Item Motivation to Read Questionnaire: Construct: Self-efficacy Scale Construct: Self-efficacy (Challenge) Q2: I like it when the questions in books make me think. 68 + 0.71 0.49 0.25 0.65 Q5: I like hard, challenging books. 68 + 0.79 0.60 0.21 0.59 Q8: If a book is interesting I don’t care how hard it is to read. 68 + 0.47 0.23 0.36 0.73 Q16: I usually learn difficult things by reading. 68 + 0.70 0.52 0.27 0.64 Q20: If the project is interesting, I can read difficult material. 67 + 0.68 0.46 0.27 0.65 0.27 0.70 Scale Construct: Intrinsic (Curiosity) Q4: If the teacher discusses something interesting I might read more about it. 68 + 0.62 0.43 0.22 0.62 Q10: I have favorite subjects that I like to read about. 67 + 0.65 0.43 0.21 0.62 Q14: I enjoy reading books about people in different countries. 68 + 0.51 0.28 0.26 0.66 Q19: I read to learn new information about topics that interest me. 68 + 0.80 0.65 0.16 0.53 Q25: I like to read about new things. 68 + 0.57 0.38 0.24 0.63 Q29: I read about my hobbies to learn more about them. 67 + 0.59 0.30 0.24 0.67 43 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) Item n Sign item-test corr. item-rest corr. Scale interitem cov. alpha 0.22 0.67 Construct: Intrinsic (Involvement) Q6: I enjoy a long, involved story or fiction book. 68 + 0.69 0.54 0.36 0.71 Q12: I make pictures in my mind when I read. 68 + 0.53 0.32 0.42 0.75 Q22: I read stories about fantasy and make believe. 68 + 0.79 0.62 0.30 0.68 Q30: I like mysteries. 67 + 0.63 0.43 0.38 0.74 Q33: I read a lot of adventure stories. 67 + 0.78 0.62 0.30 0.68 Q35: I feel like I make friends with people in good books. 67 + 0.57 0.39 0.41 0.755 0.36 0.76 Scale Construct: Extrinsic (Competition) Q1: I like being the best at reading. 67 + 0.60 0.44 0.43 0.76 Q9: I try to get more answers right than my friends. 68 + 0.70 0.47 0.37 0.73 Q41: I am willing to work hard to read better than my friends. 67 + 0.80 0.68 0.34 0.70 Q44: It is important for me to see my name on a list of good readers. 68 + 0.62 0.38 0.42 0.76 Q49: I like being the only one who knows an answer in something we read. 66 + 0.66 0.46 0.39 0.75 Q52: I like to finish my reading before other students. 67 + 0.72 0.57 0.36 0.72 0.38 0.77 Scale Construct: Extrinsic (Grades) Q3: I read to improve my grades. 67 + 0.67 0.38 0.22 0.46 Q38: Grades are a good way to see how well you are doing in reading. 67 + 0.69 0.39 0.21 0.46 Q50: I look forward to finding out my reading grade. 67 + 0.69 0.43 0.21 0.44 Q53: My parents ask me about my reading grade. 68 + 0.62 0.23 0.30 0.62 0.23 0.56 Scale 44 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read n Sign item-test corr. item-rest corr. interitem cov. Q18: My parents often tell me what a good job I am doing in reading. 66 + 0.70 0.50 0.40 Q28: I like having the teacher say I read well. 68 + 0.71 0.52 0.42 Q37: My friends sometimes tell me I am a good reader. 67 + 0.62 0.39 0.45 Q43: I like to get compliments for my reading. 67 + 0.82 0.66 0.31 Q47: I am happy when someone recognizes my reading. 66 + 0.74 0.57 0.37 Item alpha Construct: Extrinsic (Recognition) Scale 0.39 0.72 0.72 0.76 0.66 0.69 0.75 Construct: Avoidance Q13: I don’t like reading something when the words are too difficult. 67 + 0.78 0.56 0.28 Q24: I don’t like vocabulary questions. 68 + 0.66 0.41 0.39 Q32: Complicated stories are no fun to read. 68 + 0.78 0.55 0.28 Q40: I don’t like it when there are too many people in the story. 68 + 0.64 0.34 0.42 Scale 0.55 0.64 0.55 0.69 0.34 0.68 0.52 Construct: Compliance Q23: I read because I have to. 67 - 0.58 0.28 0.15 Q34: I do as little schoolwork as possible in reading. 67 - 0.49 0.20 0.17 Q36: Finishing every reading assignment is very important to me. 68 + 0.48 0.15 0.12 Q46: I always try to finish my reading on time. 67 + 0.62 0.36 0.12 Q51: I always do my reading work exactly as the teacher wants it. 67 + 0.64 0.41 0.12 Scale 0.14 0.53 0.45 0.42 0.42 0.52 Construct: Importance Q17: It is very important to me to be a good reader. 68 r=0.57 45 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) Item n Q27: In comparison to other activities I do, it is very important to me to be a good reader. 67 Sign item-test corr. item-rest corr. interitem cov. alpha p<.001 Survey of Adolescent Reading Attitudes: Construct: Academic Print Q3: How do you feel about doing research using encyclopedias (or other books) for a class? 65 + 0.76 0.59 0.86 0.69 Q6: How do you feel about reading a textbook? 67 + 0.75 0.58 0.89 0.70 Q14: How do you feel about using a dictionary for class? 65 + 0.71 0.49 0.93 0.73 Q17: How do you feel about reading a newspaper or a magazine for a class? 67 + 0.60 0.40 1.09 0.75 Q18: How do you feel about reading a novel for class? 67 + 0.75 0.58 0.90 0.70 0.93 0.76 Scale Construct: Academic Digital Q1: How do you feel about reading news online for class? 66 + 0.51 0.21 0.69 0.67 Q5: How do you feel about reading online for a class? 67 + 0.78 0.60 0.40 0.49 Q7: How do you feel about reading a book online for a class? 67 + 0.66 0.39 0.52 0.59 Q12: How do you feel about working on an internet project with classmates? 67 + 0.59 0.33 0.59 0.62 Q16: How do you feel about looking up information online for a class? 66 + 0.68 0.46 0.48 0.55 0.54 0.64 Scale Construct: Recreational Print Q2: How do you feel about reading a book in your free time? 67 + 0.88 0.81 1.51 0.83 Q8: How do you feel about talking with friends about something you’ve been reading in your free time? 66 + 0.60 0.43 2.07 0.91 46 TCR, 119, 050306 A Mixed-Methods Study of Adolescents’ Motivation to Read Item n Sign item-test corr. item-rest corr. interitem cov. alpha Q9: How do you feel about getting a book or a magazine for a present? 66 + 0.85 0.73 1.52 0.85 Q11: How do you feel about reading a book for fun on a rainy Saturday? 66 + 0.90 0.82 1.40 0.82 Q13: How do you feel about reading anything printed (book, magazine, comic books, etc.) in your free time? 67 + 0.85 0.76 1.61 0.84 1.62 0.88 Scale Construct: Recreational Digital Q4: How do you feel about texting or emailing friends in your free time? 67 + 0.91 0.83 1.37 0.70 Q10: How do you feel about texting friends in your free time? 67 + 0.91 0.80 1.27 0.70 Q15: How do you feel about using social media like Facebook or Twitter in your free time? 66 + 0.84 0.57 1.61 0.96 1.42 0.85 Scale 47 Teachers College Record, 119, 050306 (2017) MARGARET TROYER is a doctoral candidate at Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research interests include adolescent literacy, older struggling readers, and reading and writing instruction. 48