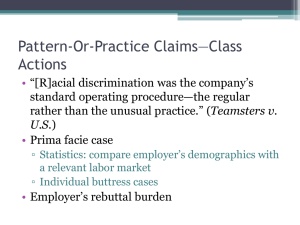

Discrimination Outline Benjamin Vanston Chapter One: Individual Disparate Impact Discrimination B. Proving Discrimination The unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people, especially on the grounds of race, age, sex… (also disability, sexual orientation, etc.) 1. What is Discrimination and How Can it be Proved? Slack v. Havens (I) Whether unlawful discrimination had occurred against the plaintiffs because of their race (F) Four black workers assigned to difficult and possibly dangerous clean-up job, which was outside of their job descriptions. White employee was excused from the assignment. Supervisor made multiple racist comments about the assignment. Workers were eventually fired. (R) Title VII – unlawful to refuse to hire, or to discharge any individual, or to otherwise discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment because of the individual’s race. (A) Causal relationship between supervisor’s conduct and the firings. Employer then ratified the discrimination with his conduct by firing the plaintiffs. Hazen Paper Co. v. Biggins (F) Biggins hired in 1977. Fired a couple weeks before his pension vested. (R) Liability under ADEA depends on whether age actually motivated the employer’s decision. ADEA commands that “employers are to evaluate employees… on their merits, not their age. The employer cannot rely on age as a proxy for various factors such as productivity, but must instead focus on these factors directly. (A) A decision by the company to fire an older employee solely because he has nine-plus years of service and is “close to vesting” would not constitute age-based discrimination. However, it is illegal under another federal employment law which involves pensions. McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green (1973) (F) Green, an African American, worked for MD in St. Louis from 1956 until 1964, when he was laid off during a general reduction of MD’s work force. Green then engaged in a protest with CORE because he thought the laying off was racially discriminatory. When he reapplied for his old position, he was not re-hired. He then sued. 1 (R) Title VII assures equality of employment opportunity and eliminates discriminatory practices and devices which disadvantage minorities. However, it does not guarantee a job to every person, regardless of qualifications. - MD-Green Factors – showing that a plaintiff (1) belongs to a racial minority (or any protected class); (2) the individual applies and was qualified for a job for which the employer was seeking applicants; (3) that, despite qualifications, he was rejected; (4) that, after his rejection, the position remained open and the employer continued to seek applicants from persons of complainant’s qualifications. - Then, the burden must shift to the employer to articulate some legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for the employer’s rejection. - Then, burden of persuasion shifts back to the plaintiff to argue that the proffered legitimate, non-discriminatory reason was pre-text for the employer’s actual discrimination. - Requirement’s for Defendant’s Rebuttal Case – First, the defendant must be able to put the reason into evidence; it is not enough to merely argue the possibility since the defendant has the burden of production. Second, the defendant must provide a sufficiently specific reason to carry its burden of production. - Pretext – the factfinder must find that both (1) the defendant’s reason is pre-textual and (2) the pretext has to be a cover-up for an underlying discriminatory motive. - General Level – Three-Step Structure – (1) the plaintiff must establish a prima facie case of discrimination, one which creates a “presumption” that the employer discriminated. Once the prima facie case has been established, the employer (2) has the burden of putting into evidence a nondiscriminatory reason for the alleged discriminatory decision. Carrying that burden destroys the presumption, but (3) the plaintiff has the opportunity to prove that the supposed reason was really a pretext of underlying discriminatory motivation. Reeves v. Sanderson Pluming Products, Inc. (2000) (R) Liability depends on whether the protected trait actually motivated the firing. If employer provides a legitimate alternative motive, the plaintiff must be afforded the opportunity to prove that these were not the defendant’s true reasons, but merely pretext. - Proof that defendant’s explanation is unworthy of credence is simply one form of circumstantial evidence that is probative of intentional discrimination, and it may be quite persuasive. In appropriate circumstances, the falsity of the explanation can cause the trier of fact to reasonable infer that the employer is dissembling a cover-up for discrimination. - Thus, a plaintiff’s prima facie case, may, combined with sufficient evidence, allow a conclusion that the employer has unlawfully discriminated. - Significance of Reeves – First, discrimination is a question of fact to be based on all the evidence in the record and the inferences that can be drawn from that evidence. Second, 2 as a party of the holistic viewpoint, ageist comments that did not qualify as “direct” evidence nevertheless could supporting drawing the inference of discrimination. Third, the Court rejected the so-called “pre-text plus” rule, that plaintiff had to adduce evidence above and beyond the prima facie case and prove the supposed non-discriminatory motive was pre-textual. 2. Everyone is Protected by Title VII McDonald v. Santa Fe Transportation Co. (1976) (R) Title VII prohibits the discharge of “any individual” because of “such individual’s race.” Additionally, Griggs v. Duke Power prohibited “discriminatory preference for any racial group, minority, or majority.” EEOC interprets it the same way. (A) (1) Santa Fe may choose to dismiss employees because of their theft of cargo, this has to be applied to members of all races alike. Crime may be a good reason for firing someone, but it is not a good reason to discriminate against someone based on their face. (2) §1981 explicitly applies to “all persons,” including white persons. The language of the bill was not meant to only protect non-whites, but whites as well. Practical Considerations (1) Employers are not always equal in their treatment – invites discrimination. (2) Employers do not always document their decisions properly. (3) Employers are not always harsh or honest in their evaluations. (4) Employers can be reluctant to admit their decisions can sometimes be arbitrary. 3. Proving Pretext Patterson v. McLean Credit Union (1989) (R) Once plaintiff established a prima facie case, an inference of discrimination is created. In order to rebut the inference, employer must present evidence that there was a legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for their actions. If they do so, petitioner has the final burden of proving the employer’s proffered reason is pretext. (A) When petitioner presents evidence of pre-text, they are not limited to presenting evidence of a certain type. The D.C. erred in instructing plaintiff that in order to succeed, she was required to show she was better qualified. In order to prove, plaintiff can present a wide range of evidence including harassment, poor treatment, etc. Ash v. Tyson Foods, Inc. (2006) - Court overturns Court of Appeals standard of determining whether the nondiscriminatory reasons for Tyson’s hiring were pre-textual. CoA stated that “pretext can be established through qualifications only when the disparity “jumps off the page and slaps you in the face.” S.C. says this is imprecise and unhelpful. Court does not adopt standard, but endorses some lower Court’s, such as “disparities in qualifications must be of such weight and significance that a reasonable person could have chosen the candidate over the plaintiff.”(citing 11th Circuit). 3 4. For What Actions is the Employer Liable? Staub v. Proctor Hospital (2011) (I) When an official has no discriminatory animus, but is influenced by company action that is the by-product of animus, can they be liable for discrimination? (A) Under tort law, the exercise of judgement by a decision-maker does not prevent an earlier agent’s discrimination from being a proximate cause of the harm. Often, an employer’s authority to reward or punish employees is spread out, with the ultimate decisionmaker relying on assessment from other employees. It would be improbable to shield the employer from liability completely if supervisors took actions which were designed and intended to produce adverse actions. - A biased report, for example, could be a causal factor in a discrimination case. C. Employment Terms, Conditions, Privileges of Employment, and Employment Practices Title VII bars discrimination in the “terms, conditions, or privileges” of employment. Hishon illustrates that a failure to promote may be actionable independent of discharge. Minor v. Centocor, Inc. (2006) (F) Minor worked for Centocor as basically a drug rep. Once her supervisor because Siciliano, she had to work much more, up to 70 to 90 hours per week Minor alleged Siciliano’s demands reflected both age and sex discrimination. (PH) District Court dismisses because Minor had not established a prima facie case. (R) Adverse employment action must constitute a “material difference” in employment that amounts to discriminatory terms and conditions. (A) Extra work can be a material difference. She was required for work 25% longer than previously, with the same exact pay. If this can be juxtaposed with favorable conditions to male (or younger) employees, this would be discrimination and violate federal law. - Minor ended up not winning her lawsuit because she could not prove race or sex discrimination. D. Linking Bias to the Adverse Employment Action Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989) (F) PW evaluates partner applications by taking comments from current partners. They can decide to approve, hold, or outright reject partnership. Great disparity between men and women with partnerships. Hopkins performed extremely well by objective evidence. Evidence shows very stereotypical negative remarks about “abrasive” woman. Including a remark that to obtain partnership, Hopkins should walk more femininely, talk more femininely, dress more femininely, wear make-up, etc. 4 (R) “The critical inquiry is whether gender was a factor at the time of the employment action. Title VII was meant to condemn decisions based on a mix of legitimate and illegitimate decisions. (A) (1) Employer shall not be liable if it can prove that, even if it had not taken gender into account, it would have come to the same decision regarding a particular person. (2) Hopkins proved that an important part of her evaluation was based on comments with sexbased stereotype and that PW in no way disclaimed those, in fact, gave her feedback based on those comments. Desert Place v. Costa (2003) (B) In Price Waterhouse, the “mixed-motive” case, the Court was divided over when the burden of proof may be shifted to an employer to prove the affirmative defense. -- Brennan – when plaintiff proves gender playing motivating part… plaintiff proves by preponderance of the evidence. Suggests limitations in the ways to prove “motivating part.” -- White – would have shifted the burden to the employer only when an unlawful motive was a substantial factor. -- O’Connor – agrees with White, but additionally would require only direct evidence. (I) Whether plaintiff must present direct evidence in order to obtain a mixed-motive instruction. (F) Costa employer as a warehouse worker, only female employee there. Costa experienced numerous problems with management which led to disciplinary sanctions. Terminated after a physical altercation with Gerber. Gerber had a clean record, but only received a 5-day suspension. Costa presented evidence at trial that she was (1) stalked by a supervisor; (2) received harsher discipline than men; (3) treated less favorably than men with respect to overtime awarded; (4) supervisors “stacked” her disciplinary record and tolerated sex-based slurs against her. (R) §2000e-2(m) states that plaintiff need only “demonstrate” that an employer used a forbidden consideration with respect to any employment practice. (A)(1) If Congress meant to include a heightened standard for showing, they would have included language which made it clear… like in Title 42 U.S.C. §5851(b)(3)(D). (2) Title VII’s silence suggest not to depart from “the conventional rule of civil litigation.” - S.C. seems to downplay the sexism of the actual case, which was worse than reflected in the facts. Gross v. FBL Financial Services, Inc. (2009) (I)(A) Whether the burden of persuasion ever shifts to the parting defending an alleged mixedmotive discrimination claim brought under the ADEA. (R) Court has never held the burden shifting framework applies to the ADEA. Unlike Title VII, ADEA does not provide plaintiff may establish discrimination by showing age was merely a “motivating factor.” Congress chose to add such a provision to the ADEA when it amended Title VII. (C)(A) Court’s interpretation of the ADEA is not governed by Title VII decisions. 5 (I)(B) Whether the ADEA authorizes mixed-motive discrimination claims. (R)(B) “It shall be unlawful… for an employer… to… discriminate because of his or her age.” (A)(B) “To establish a disparate treatment claim under the ADEA, plaintiff must prove that age was the “but-for” cause of the employer’s adverse decision. It follows that the plaintiff retains the burden of persuasion to establish age was the “but-for” cause of the employer’s decision. W.V.H.R.A. Barefoot v. Sundale Nursing Home (1995) (F) Nursing assistant Ratcliff reported that colleague, Ms. Lambert, stuck patient and cause a tear of skin on his arm. Ms. Lambert refused that she caused the tear but did not refute that she “tapped” the man. According to Sundale policy, the first offense penalty is a discharge. Lambert files suit, died, and the cause is taken up by Barefoot. (R) W.V.H.R.A. has the same analytical framework as Title VII – (1) Plaintiff must first create an inference of discrimination by establishing a prima facie case; (2) the burden then shift to the employer to proffer a legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for the challenged employment action; (3) Finally, the plaintiff has the opportunity to demonstrate the illegitimate factor was a determinative factor and the employer’s proffered reason is merely pretextual. Pretext may be shown the direct or circumstantial evidence. (A) Plaintiff presented a legally sufficient basis for which a jury could find the Defendant discriminated against her in violation of W.V.H.R.A. Plaintiff offered evidence that the plaintiff was consistent, but comparison employee was black, not N.A., therefore irrelevant. Defendant offered another employee that was N.A. with unsubstantiated evidence. – adopts Price Waterhouse + 703(m). (I)(B) Disparate Impact. (F)(B) Plaintiff also advanced a disparate impact claim because all five of its N.A. employees were fired within 6 to 8 months, beginning with the decedent. (R)(B) Plaintiff must demonstrate (1) the employer used a particular employment practice or policy and (2) establish that the particular practice or policy causes a disparate impact on a class protected by the W.V.H.R.A. (A)(B) Lack of statistical evidence; Plaintiff does not meet her burden. Skaggs v. Elk Run Coal Company, Inc. (1996) (F) Plaintiff applied to Elk Run, discussed his injuries and physical limitations. After three years, ER changes his position to require extensive physical labor. Job changes again, this time to lab technician, which still requires some physical labor. Some accommodations made. 6 (R) W.V.H.R.A. prohibits discrimination against a qualified individual with a disability. ADA additionally states that unlawful discrimination can occur when an employer fails to consider an applicant’s or employee’s disability where the adverse effect on the individual’s job can be avoided. Chapter Two: Systematic Disparate Treatment Systematic disparate treatment can be proven in two ways: (1) the plaintiff may demonstrate that the employer has an announced, formal policy of discrimination; (2) the plaintiff who cannot prove that a formal policy exists may nevertheless establish that an employer’s pattern of employment decisions reveals that a practice of disparate treatment exists. B. Formal Policies of Discrimination L.A. Dep’t of Water and Power v. Manhart (1978) (F) L.A.D.W.P. administers a collection of employee benefit programs including retirement, through fees contributed to by employees and the department. After studying mortality tables, the Department determined that women will live, on average, a few years longer than their male counterparts. They then required women to contribute 14.84% more than comparable male employees and as a result, the women took home less than the men. (R) Title VII. Focused on the individual. Even a true generalization about a class is an insufficient reason for disqualifying an individual to which the generalization does not apply. (A) (1) No assurance that any individual women will actually fit the generalization on which the Dep’t policies are based. (2) Congress had decided that classifications based upon sex are unlawful. While the mortality tables could identify differences between the sexes, the statute designed to make sex irrelevant could not reasonable by construed to permit a take-home-pay differential system based on sex. (3) Separate mortality tables are easily interpreted as representing innate differences between the sexes, although a significant part of these are overlapped with other factors (such as women smoke less than men, etc.). (4) Requiring good risks to pay for the shitty risks is how all insurance works. (5) whether or not there was animus is irrelevant; however, in the particular case, there was a pretty good argument that animus was involved. C. Patterns and Practices of Discrimination Teamsters v. United States (1977) (F) Central claim was that the company had engaged in a pattern or practice of discriminating against minorities, in hiring “line-drivers.” Were given lower-paying, less-desirable jobs, discriminated against with respect to promotions and transfers. (R) Gov’t bares the burden of making out a prima facie case. Because it alleged a systemwide pattern or practice of discrimination, the gov’t ultimately must prove more than a mere occurrence. It must establish by preponderance of the evidence that racial discrimination was the Company’s standard operating procedure. 7 (A) (1) Only eight African American line drivers and 5 Spanish American line drivers, all of the AA drivers had been hired after litigation began. (2) Numerous qualified drivers who sought jobs at the company either were ignored, given false information, or not considered at all. Additionally, transfers were treated the same way. (3) Statistical analysis matters when establishing a prima facie case, and this one is stark. (C) Gov’t established a prima facie case. - “Absent explanation, it is ordinarily to be expected that nondiscriminatory hiring practices will in time result in a work force more or less representative of the racial and ethnic composition of the population in the community from which employees are hired.” (1) Plaintiff puts on evidence of discrimination, creates a presumption of racial discrimination; (2) employer has to opportunity to rebut this inference. Hazelwood School District v. United States (1977) (F) Personnel office began practice of interviewing 3 to 10 applicants when a vacancy existed. Principles had virtually unlimited discretion. A number of applicants who were not hired were AA. Hazelwood hired its first AA in 1969. Number of AA faculty increased in successive years: 6 / 957 in ’70; 16 / 1,107 in ’71; 22 / 1,231 in ’73. (R) “Establish by preponderance of the evidence that racial discrimination was the employer’s standard operating procedure. Where gross statistical disparities can be shown, they alone may constitute a prima facie case of pattern or practice of discrimination.” (A) (1) D.C. statistical comparison of teacher’s to pupils “fundamentally misconceived” the role of statistics in discrimination cases. (2) CoA totally disregarded the possibility that the prima facie statistical proof might be rebutted by statistics of how it handled hiring after it became subject to Title VII. (3) Difference between these figures may be important, it may be sufficient to weaken the government’s proof and it could be large enough to reinforce it. Factors for Labor Pool – (a) applicant flow data; (b) geographical area; (c) ease of commute / availability of public transportation; (d) skills / interests of population; (e) employers’ recruitment practices; (f) time. Bastress’s List – (1) time; (2) relevant qualifications; (3) geography Calculating Z-Score – PAGE 124 HAS ALL THE INFORMATION IF NEEDED TO ON THE EXAM. 8 D. Defenses to Disparate Treatment Cases 1. Rebutting the Inference of Discriminatory Intent Personnel Administrator v. Feeny (1979) - “’Discriminatory purpose’” implies more than intent as volition or intent as awareness of the consequences. It implies that the decisionmaker, in this case a state legislature, selected or reaffirmed a particular course of action at least in part ‘because of,’ not merely ‘in spite of,’ its adverse effects upon an identifiable group.” EEOC v. Sears, Roebuck, and Co. (1988) (F) EEOC challenged Sear’s hiring, promotion, and firing practices for systematic disparate treatment, on the basis of gender. EEOC presented, almost exclusively, statistical evidence from rejected applicants and payroll records. (R) Teamsters: “we do not… suggest that there are any particular limits on the types of evidence an employer may use.” (A) Reject EEOC’s contention that Sear’s interest evidence was insufficient as a matter of law to undermine EEOC’s statistical evidence. Not clearly erroneous: (1) commission selling was different than non-commission selling; (2) women were not interested as men in commission selling; (3) women were not as qualified for commission selling than men. 2. Bona Fide Occupational Qualifications (BFOQ) §703(e) of Title VII: “… it shall not be an unlawful employment practice for any employer to hire and employ employees… on the basis of religion, sex, or national origin in those certain instances where [the forbidden class] is a bona fide occupation qualification reasonable necessary to the normal operation of that particular business or enterprise. - Important to remember that there is no BFOQ for race discrimination. Dothard v. Rawlinson (1977) “BFOQ is an extremely narrow exception to the general prohibition of discrimination on the basis of sex.” - AL penitentiaries women could not perform “contact jobs” because they could not perform the “essence of the correctional counselor’s job.” Western Airlines v. Criswell (1985) Supreme Court approved a jury instruction hat allowed that airline to establish a BFOQ by showing (1) “it was highly impractical for Western to deal with each 2nd officer over 60 on an individual basis to determine his particular ability to perform his job safely; (2) “some 2 nd officers over the age of 60 possess traits of physiological, psychological, or other nature which preclude safe and efficient job performance that cannot be ascertained by means other than knowing their age.” - Alternative Test for BFOQ – if “all or substantially all” in the persons in the disfavored group “would be unable to perform safely and efficiently the duties of the job involved.” 9 Customer Preference – cannot make out a BFOQ. Privacy could be an exception to this rule. Int’l Union, UAW v. Johnson Controls, Inc. (1991) (F) In the battery manufacturing process, the element lead is a primary ingredient. Occupational exposure leads to health risks, including the risk of harm to a fetus. Because of this, Johnson Controls excludes women who can become pregnant and women that are pregnant from working certain jobs. (R) §703(a) prohibits sex-based classifications in the terms and conditions of employment. Additionally, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act explicitly says that for the purposes of Title VII, pregnancy discrimination equal sex discrimination. (A) (1) Johnson Controls policy classifies on gender + fertility rather than simply fertility. JC is concerned only with the harms on female offspring, not the fertility of males. (2) Under PDA, this comes out the exact same way. (IV)(R) BFOQ is narrow. Has to be more than a danger to a women herself. Additionally, in order to qualify for a BFOQ, the qualification must relate to the “essence” of the job. (IV)(A) Unconceived fetuses are neither customers nor third parties whose safety is essential to battery manufacturing. BFOQ not so broad that is transforms social concern into an essential aspect of battery manufacturing. - Pregnant women or otherwise must be treated like others in their ability to work. Capable women may not be forced to chose between having a child and a job. Bottom Line : reasonably necessary to the normal operations of the business. (1) Occupational Qualification – “has to relate to the ability to do the job” (2) has to relate to the essence of the business (3) employer must show (a) all members of the class are unable to do the job; or (b) all or substantially all members of the class are unable to do the job AND individual determinations are not possible. - “Safety” must relate to third parties – other workers and customers – and not to the individual alone. - “Authenticity” – we think this exception exists as a BFOQ, but there is very little litigation over it. // actors + law enforcement. 3. Voluntary Affirmative Action Johnson v. Transportation Agency of S.C. County (F) TASCC adopts Affirmative Action plan to remedy a disparity in roles traditionally filled by men. Agency states that its long-term goal was to attain a work force that reflected the proportion of women and minorities in the labor force. However, the plan acknowledged that a number of factors may make it unrealistic to rely on the long-term goals for the current employment decisions. The plan based its decisions on short-term goals. - Johnson and Joyce applied for the position of road dispatcher. They are both deemed qualified. Johnson received a higher score than Joyce, by two points. Joyce contacted the County’s Affirmative Action office because she thought that she would not get a fair shake. Graebner 10 authorized to make a choice between any of the candidates which were deemed qualified. Graebner chose Joyce. (R) The existence of an affirmative action plan counts as a nondiscriminatory rationale for an employment decision. A valid plan cannot unnecessarily trammel the interests of white employees nor serve as an absolute bar to the advancement of white people within the workplace. To adopt a plan, an employer need not point to its own prior discrimination nor assemble evidence of a prima facie case. - “manifest imbalance” – in determining whether an imbalance exists, a comparison of the percentage of minority employees in the employer’s workforce with the percentage in the area labor market. However, when analyzing a job that requires special training, the comparison should be similar to Hazelwood. (A) (1) The plan was “narrowly-tailored” to remedy disparities in the employment of minorities while taking into account the realistic goals and not establishing strict quotas, but reasonable aspirations. (2) Furthermore, the plan did not “unnecessarily trammel” on the rights of majority employees, rather only authorized considerations of AA concerns. Additionally, the agency director was not limited to only hiring Joyce. - Once put at issue, the plaintiff must establish that an AA plan is invalid. Burden never shifts to the defendant. - Two-step – (1) Preliminary – whether there is a manifest imbalance; (2) unnecessarily trammel the rights of majority employees or create an absolute bar to the advancement of them. - Considerations: (1) Duration of the plan; (2) “reasonableness”; (3) no automatic disqualifications of the majority employees or applicants. Need to have a written, formal affirmative action plan, not an ad hoc one. - Diversity rationale does not apply to Title VII. B. The Relationship between Individual Disparate Treatment and Disparate Impact Often litigants try to pursue both theories; however, the disparate impact analysis is neither necessary nor relevant in a pure disparate treatment case. C. Relationship between Systematic Disparate Treatment and Disparate Impact 3. Applying the Two Systematic Theories in one case EEOC v. Dial Corp. (2006) (F) Dial owns sausage plant. Entry level employees are assigned to the sausage packing area where they are required to lift and carry loads of sausage. Employees working in this section experienced a disproportionate number of injuries. Dial implemented measures in 1996 to reduce 11 the number of injuries, all were changes to how the employees conducted their operations. Dial added additional requirement in 2000, a strength test. Percentage of women who passed decreased each year; however, injuries also declined. Testimony suggesting Dial knew of the effect but decrease of injuries warranted continued use. EEOC brings both Systematic Disparate Treatment and Disparate Impact. (R) All the SDT rules. (A) Hiring disparity was 10 standard deviations away from where it was expected. Percentage of women decreased each year of the test being used. Content validity guidelines – decrease in injuries happened before the test was adopted. Injury rate for women was lower in two out of the three years before Dial implemented the test. Chapter Three: Disparate Impact Discrimination Disparate impact discrimination has no intent requirement: it applies to employment practices that adversely affect one group more than another and cannot be adequately justified. A. The Concept of Disparate Impact Discrimination Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971) (F) At the time litigation started, Duke had 95 employees at the Dan River station, 14 of whom were African American. Prior to enforcement of the Civil Rights Act, Duke openly discriminated, only having black employees in the Labor Department. They then instituted a policy of requiring high school diplomas for every department except for Labor. Then they made it a requirement to transfer from Labor to any other department within Duke. Then they instituted a policy of needing to have satisfactory scores on two independent examinations. Neither test was directed or intended to measure the ability to learn to perform a particular job or category of jobs. (R) Under Title VII, practices, procedures, or test neutral on their face, and even neutral in their intent, cannot be maintained if they operate to “freeze” the status quo of prior discriminatory employment practices. (A) (1) Neither the high school requirement nor the test bore a demonstrable relationship to successful performance of jobs when it was used. (2) Good intent or the absence of discriminatory intent does not redeem the procedures that operate as “built-in headwinds” for minority groups and are unrelated to job performance. (3) Legislative history + EEOC regulation 703(h). 12 Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio (1989) (Read Again) (F) Disparate impact claims from salmon canneries in remote Alaska. Jobs at the canneries are two types: (1) Cannery jobs, which entail unskilled labor and (2) “Non-Cannery,” which entails skilled labor. Cannery jobs are primarily filled with nonwhites. Non-Cannery jobs are predominately filled with white workers, mostly hired out of the company’s offices in Oregon and Washington. (R) the proper comparison is between the racial composition of [the at-issue jobs] and the racial composition of the qualified… population in the relevant labor market. Alternatively, in cases where such labor market statistics would be too difficult to ascertain, other statistics – such as measures indicating the racial composition of “otherwise qualified nonapplicants” for the at-issue jobs – are equally probative for this purpose. (A) Measuring the “skilled” non-cannery positions by comparing the number of nonwhites filling cannery jobs is nonsensical. Must make a comparison between the relevant labor pool and the positions filled. - Burden of persuasion always with the plaintiff Gone from the touchstone being “business necessity” to “a reasoned review of the employer’s justifications for his use of the challenged practice.” B. Disparate Impact Law after the 1991 Civil Right Act 1. Plaintiff’s Prima Facie Case a. Particular Employment Practice The plaintiff carries the burden of persuasion that the employer “uses a particular employment practice that causes disparate impact on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. - Two questions: (1) is every employment-related action of an employer a qualifying “employment practice?”; (2) how does the plaintiff establish that a disparate impact resulted from a “particular practice” as opposed to a congeries of causes? Watson v. Fort Worth Bank and Trust (1988) (1) A facially neutral practice, adopted without discriminatory intent, may have effects that are indistinguishable from one that has been. Does not follow that a subjective consideration is always without discriminatory intent or effects. (2) If employer’s undisciplined system of decision-making has precisely the same effects as one of intentional discrimination, Title VII should apply in the same way. Connecticut v. Teal (1982) (F) To attain permanent status as supervisors, the selection process required a written exam. Administered to 329 candidates, 48 black and 259 white. 54.17% of blacks passed, 68% of whites passed. In choosing from the list, defendant considered several other factors. 46 individuals were promoted, 11 black and 35 white. The overall result was 22.9% of original black applicants were promoted and 13.5% of whites were promoted. Thus, the “bottom-line” result was more favorable to blacks, even though the test had a disparate impact. 13 (A) No “bottom-line” complete defense to disparate impact. A racially balanced workforce cannot immunize from liability for specific acts of discrimination. b. The Employer Uses the Practice §703(k)(1)(A)(i) requires that the plaintiff prove that the employer “uses a particular employment practice that causes a disparate impact. Dothard v. Rawlinson (1977) (F) Rawlinson applied to be a correctional counselor and was refused because she did not meet a height and weight requirement. Alabama women held only 12.9% of counselor positions. The height and weight requirements would exclude 41.13% of females, while only excluding less than 1% of males. (R) Plaintiff needs to show the facially neutral standards in question select applicants for hire in a significantly discriminatory pattern. Once this burden is met, the employer must show the requirement has a manifest relationship to the employment in question. If the employer meets that burden, the plaintiff may show other selection devices without a similar discriminatory effect would also serve the employer’s legitimate interests. (A) (1) No requirement that the statistical showing of disparate impact must always be based on the characteristics of actual applicants. Reliance on more general statistics was not misplaced when there is no reason to think Alabama men and women significantly differ from the rest of the country. c. The Quantum Impact Plaintiff must prove that the practice challenged “causes a disparate impact,” but it does not define “disparate” in terms of the quantum impact that suffices. - EEOC will only challenge substantial adverse impact – means will only investigate when the selection rate is 80%. You can also inverse pass rates and fail rates and make meaningful changes. Look at notes for more details. - This line is less clear when it comes to private cases. 2. Defendant’s Options a. Rebuttal: The Employer’s Use does not cause impact An employer may try to undermine the plaintiff’s showing of a prima facie case by introducing evidence that the data the plaintiff relied on was flawed. b. Business Necessity and Job Relatedness El v. S.E. PA Trans. Auth. (2007) (F) At-issue practice is the disqualification of anyone convicted of a violent crime. (A)(1) Court refuses to accept “common sense” assertions of business necessity and requires some empirical proof that the challenged hiring criteria accurately predicted job performance. (A)(2) Court rejects the “more is better” argument… that some abstract notion of a good given quality is better when there is more… is insufficient to justify discrimination. 14 (A)(3) Hiring criteria must effectively measure the minimum qualifications for successful performance of the job in question. However, hiring policies need not be perfectly tailored to be consistent with business necessity. - require that a discriminatory hiring policy accurately – but not perfectly – ascertains an applicant’s ability to perform successfully in the job in question. 3. Alternative Employment Practices “If an employer does then meet the burden of proving the tests are “job-related,” it remains open to the complaining party to show that other test or selection devices, without similarly undesirable racial effects, would also serve the employer’s legitimate interest. Such a showing would be evidence that the employer was using its tests merely as a “pre-text” for discrimination.” Jones v. City of Boston (2016) (F) Boston PD administered drug-test to thousands of applicants, cadets, officers. (I) Whether the tests’ results could be meaningfully relied upon. Some evidence that cosmetic products used by black people generate false positives. Additionally, tests may be triggered through environmental exposure. (A) Plaintiff must demonstrate a viable alternative and give the employer time to adopt it. Suggests this means the alternative exists and the employer is free to adopt it. Two Lines of Cases – (1) “Alternative practices” means establishing intentional discriminatory reason for not adopting the alternative OR (2) just that there was an ulterior motive to use the test other than the proffered reason. C. §703(h) Exceptions 1. Professional Developed Tests §703(h) provides that “notwithstanding any provision of Title VII, it shall not be an unlawful employment practice of an employer to give and to act upon the results of professionally developed ability tests provided that such a test, its administration, or action upon the results is not designed, intended, or used to discriminate because of color, race, or national origin. Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody (1975) (F) Company had a long history of overt discrimination. Discontinued that but established two different tests which workers needed to pass in order to transfer departments. Few black workers passed. Not required for those who already transferred, but some white incumbents who could not pass were retained anyways. Also, Company established a high school grad requirement and kept it, even after finding it did not improve the workforce. Hired an expert, but they did their own study without the expert’s supervision. Study dealt with 10 group from near the top of nine lines of progression. No attempt was made to analyze the jobs in terms of the particular skills they required. (R) Griggs. EEOC guidelines. 15 (A) (1) Even if otherwise reliable, the patchwork study would not entitled Defendant to continue the testing program. The study does not analyze the skills required for the job. No basis for concluding that “no significant differences exist” along the lines of progression. (2) Supervisors were given extremely broad and subjective criteria to rank in test validation, no way of knowing what the precise criteria was. (3) The fact that the best employees working near the top of a line progression score well does not necessarily mean that the test is a permissible measure of the minimum qualifications of new workers entering entry level positions. - EEOC guidelines now provide three generally accepted validation strategies: (1) criterion; (2) content; or (3) construct. Content validation used a sample of the work done on the job as the test. If the sample is really representative of the job, success on the test necessarily implies success on the job. 2. Bona Fide Seniority Systems §703(h) provides an exception to Title VII liability for seniority systems: “It shall not be unlawful… to apply different standards of compensation, or different terms, conditions, or privileges of employment to a bona fide seniority or merit system. Int’l Brotherhood of Teamsters v. U.S. – S.C. held that the mere perpetuation of earlier discrimination does not make a seniority provision in a collective bargaining agreement illegal. 3. Bona Fide Merit and Piecework Systems Systems that measure compensation by quality of production. The more a worker produces, the more he/she gets paid. Chapter Four – Interrelation of the Three Theories of Discrimination A. Interrelation between Individual and Systematic Disparate Treatment Baylie v. FED of Chicago “Statistic analysis does not tell us – in any civil litigation – where the plaintiff’s burden is to show more likely than not he was harmed by a legal wrong, data of this kind will not get him over the threshold. It must be coupled with other evidence.” Here, plaintiff’s evidence showed a disparate impact; however, when the data was narrowed to only full-time employees, black workers were slightly more likely to be promoted. Relationship of the Systematic Theories - Proof of impact can make out both plaintiff’s initial showings, but rarely will be sufficient to make out a showing of intentional discrimination. - **Sometimes a defense rebutting systematic disparate treatment can make out the plaintiff’s disparate impact prima facie showing** 16 D. Reconciling the Tension between Disparate Treatment and Impact Ricci v. DeStefano (2009) (F) NH hired firm who specializes in written examinations for fire and police departments. After developing through an extensive process, city gives out exam to candidates for promotion. The results statistically make out a disparate impact claim. City is forced to choose between facing a disparate impact claim and a disparate treatment claim from candidates who were successful on exam. - Analysis begins with premise the City would violate disparate treatment absent a valid defense. Because the City chose not to certify the exam results because an existing disparity in racial statistics. - Whatever the City’s intentions, it made an employment decision because of race --- Adopts strong-basis-in-evidence standard because it leaves room for employer compliance and appropriately constraints employer discretion in race-based decisions. ---- No SBIE because there is no dispute that the exams were job-related and consistent with business necessity. Additionally, lacked the same standard for an alternative test. Chapter Five – Special Problems in Applying Title VII, §1981, and ADEA B. Coverage Who is an employer? Is there a “employer relationship” between the employer and the adversely affected individual? Employer: 15 or more employees for twenty or more weeks – Title VII; 20 or more employees for 20 or more weeks – ADEA; - State and local governments, generally, are subject to the employer role. ADEA does not requires 20/20 rule. WVHRA does not either. Title VII is extraterritorial. However, they have affirmative defense for obeying laws in other countries. Employees include applicants and former employees fired for discrimination No individual liability under Title VII, only the agency. Same with ADEA. WVHRA does have individual liability, but it is a totally open ended tort. §1981 has individual liability as well, ongoing dispute whether is applies to local governments. 17 C. Sex Discrimination 1. Discrimination “because of sex” Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc. (1998) (H) Nothing in Title VII bars a claim of discrimination because the plaintiff and defendant are of the same sex. (A) (1)**Critical issue is whether members of one sex are exposed to disadvantageous terms or conditions to which members of the other sex are not.** (2) Title VII does not turn into a “general civility code…” it only forbids behavior so objective offensive as to alter the “conditions” of the victim’s employment. a. Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation Harassment based on the failure on conform to gender-stereotypes is “because of sex.” However, long and equally firm consensus that Title VII does not bar discrimination based on sexual orientation. Cases uniform until about six years ago, represents a crazy fast change. Hively v. Ivy Tech Comm. College (2017) (I) Court decides whether actions taken on the basis of sexual orientation are a subset of actions taken on the basis of sex. (A) (1) Here, the workplace practice does not reach every man and woman, but it is based on assumptions about the proper behavior for someone of a given sex. The discriminatory behavior does not exist without taking the victim’s biological sex into account. (2) If we change the sex of one partner in a lesbian relationship, the outcome would be different. Reveals the discrimination rests on assumptions about sex. - (1) Comparative method; (2) Associational theory; (3) Stereotype conformity; (4) Sex+ cases… the sex of the employee, plus some other consideration. b. Personal Relationships What happens when employee uses his/her sexual attractiveness to obtain an advantageous relationship with the employer? – DeCintio v. Westchester – unfair, but not actionable. c. Grooming / Dress Codes Jespersen v. Harrah’s (2006) As long as no grooming / dress codes requirements are more burdensome on one employee than the other, they can differ on the basis of gender. 18 d. Discrimination Because of Pregnancy Young v. UPS The Act requires courts to consider the extent to which an employer’s policy treats pregnant workers less favorably than it treats nonpregnant workers similar in their ability or inability to work. Additionally, it requires courts to consider legitimate, nondiscriminatory non-pretextual justification for these differences in treatment. The plaintiff, in turn, show that the employer’s proffered reasons are pre-textual. Ultimately, the court must determine whether the nature of the employer’s policy and the way in which it burdens pregnant women shows that the employer has engaged in intentional discrimination. 2. Sexual and Other Discriminatory Harassment Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (1986) “For sexual harassment to be actionable, it must be sufficiently severe or pervasive to alter the conditions of employment and create an abusive working environment.” - “Voluntary” not a defense – “unwelcome” is the key threshold a. Severe or Pervasive Harassment Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc. (1993) (1) Hostile and abusive can be determined by looking towards all the circumstances; (2) we can say that whether an environment is “hostile” or “abusive” can be determined by looking at the (1) frequency of the discriminatory conduct; (2) its severity; (3) whether physically threatening, humiliating, or a mere offensive utterance; and (4) whether it interferes with employment. National R.R. v. Morgan – S.C. holds that “the entire scope of a hostile work environment claim, including behavior alleged outside the statutory time period, is permissible for the purposes of assessing liability, so long as any act contributing to that same hostile working environment takes place within the statutory time period.” d. Vicarious Liability Burlington Industries v. Ellerth (1998) Vicarious liability arises with aid, negligence, or apparent authority. “An employer is subject to vicarious liability to a victimized employee for an actionable hostile work environment created by a supervisor with immediate (or successively higher) authority over the employee. When no tangible employment action is taken, a defending employer may raise an affirmative defense to liability or damages, subject to proof by preponderance of the evidence. The defense comprises two necessary elements: (a) that the employer exercised reasonable care to prevent and correct promptly any sexually harassing behavior; (b) the plaintiff unreasonably failed to take advantage of any preventative or corrective opportunities provided by the employer or to avoid harm otherwise.” 19 Vance v. Ball State (2013) Holds that under the Ellerth / Faragher framework, an employee is a “supervisor” for purposes of vicarious liability if he / she is empowered by the employer to take tangible employment actions against the victims. D. Discrimination on Account of Religion Title VII prohibits discrimination based on religion; however, the statute goes further to introduce the duty to reasonably accommodate religious practices and observations. EEOC v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, Inc. Statutory language does not require knowledge. Intentional discrimination prevents motives, therefore, an employer acting with the motive of avoiding religious accommodation would violate Title VII even if based on a mere suspicion. The Duty to Reasonably Accommodate The broad formulation of the “reasonable accommodation” clause suggest that religious observations are privileged as opposed to secular practice. However, not necessarily the case. “Undue Hardship” – anything more the de minimus. Rationale is that anything more than that, it might be favoring one religion over the other. When an employer does offer a reasonable accommodation, that satisfies their Title VII duty even if another accommodation may be viewed as better. Hosanna-Tabor v. EEOC (2012) (A) Requiring a church to accept or retain unwanted minister is more than a mere employment decision, it interferes with the internal governance of church. Establishment clause overpowers it. Ministerial exception to ADA, E. National Origin and Alienage Discrimination Title VII has been held not to bar alienage discrimination, despite its close connection with national origin. Espinoza v. Farah Mig. Co. (1973) §1981 prohibits much of what might now be called national origin discrimination because of the broader meaning of “race” at the time of its passing. §1981 has been held to prohibit alienage discrimination. Public employers must do equal protection analysis. States and local gov may insit on citizenship for positions that promote some civic purpose. (law enforcement, public school teachers, elected/policy making positions) F. Union Liability 20 G. Age Discrimination Plaintiff claiming age discrimination must prove that discrimination was a determinative factor in the challenged decision. Gross v. FBL Services. ADEA has a BFOQ exception. Disparate impact is actionable, but is subject to much looser scrutiny because of the “reasonable factors other than age” language. 1. Exception for Policemen and Firefighters ADEA permits states and political subdivisions to set age limitations both for hire and for discharge after 55 for law enforcement and firefighters. 2. Bona Fide Benefit Plans General Dynamic Land Sys. (2004) – held that favoring older workers over younger workers in the protected class is not prohibited by the statute. BFEBP – an employer will not violate the statute if it either (1) provides its workers with equal benefits or (2) practices age-differentiated benefits but incurs equal costs in doing so. 3. Early Retirement Incentive Plans ADEA permits these, subject to certain limitations. See page 404. Chapter 6 – Retaliation In addition to prohibiting discrimination on certain grounds, Title VII, §1981, and ADEA also creates a remedy for certain retaliatory conduct. B. Who is Protected? Thompson v. North American Stainless, LP (2011) (F) Thompson gets fired after his fiancée filed charges against the same company through the EEOC. (I)(1) Does NAS’s firing of Thompson constitute unlawful discriminatory retaliation? (R) Title VII’s antiretaliation provision prohibits any employer action that “well might have dissuaded a reasonably worker from making or supporting a charge of discrimination.” (A) Obvious that a person would be dissuaded from bringing a charge of discrimination if they knew their fiancée would be fired for it. (I)(2) Whether Thompson may sue NAS for its alleged violation of Title VII. (R) A civil action may be brought… by the person claiming to be aggrieved.” (A) Establishes “zone of interests” test. Plaintiff cannot sue “if the plaintiff’s interests are so marginally related that it cannot reasonably be assumed that Congress intended to permit the suit.” --- Thompson falls within the zone of interest. He is not an accidental victim of an 21 employer’s unlawful act. The employer intended to harm him in order to retaliate against his fiancée. C. Distinguishing Participation from Opposition Clark County School District v. Breeden (2001) (F) Breeden met with two supervisors who were reviewing job applications. One applicant admitted to making derogatory jokes about women in the past. Two supervisors laughed. Breeden sued on two different grounds of retaliation. She was up to transfer after this incident, but it was unrelated. (R) Sexual Harassment must be “severe and pervasive.” (A) Nobody could reasonably believed this incident was in violation of Title VII. It is in her job description to review applicants. At best, it is slightly inappropriate. (2) Plaintiff must show the existence of a causal connection between protected activities and the transfer. Respondent did not serve the employer with complaint until a day after her supervisor said she was considering a transfer for Breeden. (3) There is no evidence supervisor knew about the right-to-sue letter, but if she did, you would also have to presume that she knew about it almost two years before the protected action. Such a length of time between two events could not be reasonably construed to have a causal connection. • Plaintiff invoking the opposition clause must demonstrate, at the least, a reasonable, good faith belief that the conduct complained of is unlawful. The participation does not have that requirement. D. The Scope of Participation Protection Participation involves formal activities, such as filing a EEOC charge or testifying. Courts are very protective of this kind of conduct. Laughlin v. MWAA (1998) (F) Really complex facts. Essentially L thought there was a cover-up effort by an EEOC officer at MWAA. She made copies of an unsent warning letter with newspaper clippings of the person’s promotion to the original complainant. L was fired for revealing classified information. (R) To establish a prima facie case of retaliation, plaintiff must prove that she: (1) engaged in protected activity; (2) that an adverse employment action was taken against her; (3) that there was a causal link between the protected activity and the adverse employment action. (A)(1)(part.) Evidence does not support the assertion that L participated. There was no ongoing formalized investigation or lawsuit. Complainant had no requested L’s assistance. (A)(2)(opp.) Balancing Test: Employer’s interest in maintaining security and confidentiality against individual’s interest in reasonably engaging in activities opposing discrimination. Here, L’s actions were not reasonable. 22 E. Adverse Action Burlington R.R. v. White (2006) (1) Retaliatory discrimination does not have to be confined to the workplace. Title VII’s goals would not be achieved otherwise because there are plenty of adverse actions an employer can take against an employee from outside the workplace. c (2) Anti-retaliation provision protects an individual not from all retaliation, but one that produces injury or harm. - Plaintiff must show that a reasonable employee would have found the challenged action materially adverse which “would have dissuaded a reasonable worker from making or supporting a charge of discrimination.” F. Causation Retaliation must be proved according to traditional principles of but-for causation. This requires proof that the unlawful retaliation would not have occurred in the absence of the alleged wrongful action or actions of the employer. Texas Southwestern v. Nassar WVHRA – expressly prohibits retaliation, sub §(b) prohibits obstruction of a claim and sub§(a) prohibits a course of conduct “designed to injure.” Chapter Seven – Disability Discrimination ADA – First, the statute protects only an individual with a disability who is qualified, which means that employers are permitted to engage in disparate treatment when the disabled employee is unable to perform the essential functions of the job with or without reasonable accommodation. Counterbalancing this, disabled individuals are entitled to the employer’s affirmative duty to provide “reasonable accommodation” (short of “undue hardship”) to ensure that individuals with disabilities have equal employment opportunities. B. The Meaning of “Disability” §12103(1) defines “disability” as (a) a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of… an individual; (b) a record of such impairment; or (c) being regarded as having such an impairment. 1. Actual Disability First, we consider whether there is a physical or mental impairment. Second, we identify the life activity upon which the plaintiff relies and determine whether it constitutes a major life activity under the ADA. Third, we ask whether the impairment substantially limits the major life activity. 23 - The Act “indisputably applies to numerous conditions that may be caused or exacerbated by voluntary conduct such as alcoholism, AIDS, diabetes, cancer, etc. 2. Record of Such an Impairment Obvious meaning. Does not have to be currently “substantially limiting” but did need to be at the time of the disability. These people are entitled to reasonable accommodations. (ex. Routine checkups) 3. Regarded as Having Such an Impairment Sutton v. United Air Lines, Inc. (1999) (R) Under Subsection (C) individuals who are “regarded as” having a disability are disabled within the meaning of the ADA. Subsection (C) provides that having a disability includes “being regarded as having” … “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of such individual. There are two apparent ways in which individual may fall within the statutory definition: (1) a covered entity mistakenly believes that a person has a physical impairment which substantially limits one or more major life activities; or (2) a covered entity mistakenly believes that an actual, nonlimiting impairment substantially limits one or more major life activities. Alexander v. WMATA (D.C. 2016) Plaintiff must establish he has a disability with regard to the ADA under the Rehabilitation Act. C. The Meaning of Qualified Individual Establishing a disability is not enough, must also show they are qualified. - Numerous decisions reject claims because a plaintiff’s disability prevent them from performing essential functions which cannot be accommodated. - However, ADA protects those who can perform the essential tasks of their jobs even if they cannot do the marginal or relatively unimportant aspects. - Necessary to distinguish between essential functions and those which are not. 1. Essential Job Functions Rehrs v. The Iams Company (R) An individual is qualified if he satisfies the requisite skill, experience, education, and other job-related requirements, and “can perform the essential job functions with or without reasonable accommodation.” Essential functions are the fundamental job duties but not the marginal functions of a particular job. An employer has the burden of showing a particular job function is an essential function of the job. (A) All factors weigh on the side of Iams Company. Shift requirements upheld. Kind of bullshit, but whatever. 24 EEOC v. The Picture People (6th Cir. 2012) (R) Whether such skills are an essential function depends in part upon whether the employer “actually requires all employees in the particular position to satisfy the alleged job-related requirementd.” Factors to consider are: (a) the employer’s judgement as to which functions are essential; (b) written job descriptions prepared before advertising or interviewing applicants for the job; (c) the amount of time spent on the job performing the function; (d) the consequences of not requiring the incumbent to perform the function; (e) the terms of a collective bargaining agreement; (f) the work experience of past incumbents in the job, and / or; (g) the current work experience of incumbents in similar jobs. 2. The Duty of Reasonable Accommodations A qualified individual with a disability is one who can perform the essential functions of the job she holds or desires with or without reasonable accommodation. In appropriate circumstances, the employer must take affirmative steps that will allow disabled employees to perform their jobs. U.S. Airways v. Barnett (R) ADA says that discrimination includes an employer’s not making reasonable accommodations to the known physical or mental limitations of an otherwise qualified… employee, unless the employer can demonstrate that the accommodation would impose an undue hardship on the operation of its business. ADA says that reasonable accommodation may include reassignment to a vacant condition. - Seniority systems trump the requirement to provide reasonable accommodations unless the plaintiff shows special circumstances that make an exception from the seniority system reasonable in the particular case. Van Zande v. State of Wisconsin Department of Administration (7th Cir. 1995) Bullshit case. Gambini v. Total Renal Care, Inc. (2007) Conduct resulting from a disability is considered a part of the disability, rather than a separate basis for termination. As a practical result of that rule, where an employee demonstrates a causal link between the disability-produced conduct and the termination, a jury must be instructed that it may find that the employee was terminated on the impermissible basis of her disability. (A) Gambini had bi-polar disorder. Had outbursts. Employer fired her for those outbursts. Employer must be found liable if there is a causal link between her outburst and her bipolar disorder. 25 3. Undue Hardship A claimed failure to accommodate can be defended on the ground that even an otherwise reasonable accommodation would pose an “undue hardship” on the operation of the employer’s business. The ADA provides that an “undue hardship” is an accommodation requiring “significant difficulty or expense,” which must be determined by considering all relevant factors, including the size and financial resources of the covered entity. Burden on the employer. D. Discriminatory Qualification Standards 1. Direct Threat ADA §103(b) provides that “the term ‘qualification standards’ may include a requirement that an individual shall not pose a direct threat to the health and safety of other individuals in the workplace.” The EEOC requires the “direct threat” determination to be based on a reasonable medical judgement that considers such factors as the duration of the risk, the nature and severity of the potential harm, the likelihood of potential harm, and the imminence of the potential harm. Chevron, USA v. Echazabal (2002) EEOC regulation authorizing refusal to rehire an individual because his performance on the job would endanger his own health, owing to a disability. Court holds the regulation is allowed. 2. Job Relatedness and Consistent with Business Necessity E. Special Problems of Disability Discrimination 1. Drugs or Alcohol Employer cannot discriminate against an individual who has a history of drug or alcohol abuse. However, they can discriminate against someone who is currently abusing drugs or alcohol. 2. Medical Examinations and Inquires An employer is prohibited from using a medical examination or inquiry to determine whether a job applicant has a disability or the nature and severity of such a disability. However, the employer (1) may inquire into the applicant’s ability to do the job before making a job offer; and (2) may condition an offer of employment on results of a medical examination if certain conditions are met. These include subjecting all new employees to medical examinations and keeping the results confidential. Such medical examinations given after an offer of employment has been made but prior to the commencement of employment need not be job related or consistent with business necessity. 26 27