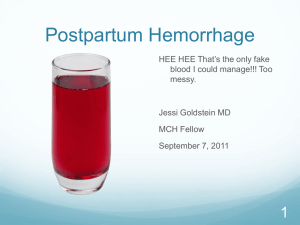

Trainee’s Corner Management of Postprocedural Uterine Artery Embolization Pain Johannes L. du Pisanie, MD1 Clayton W. Commander, MD, PhD1 1 Department of Radiology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina Charles T. Burke, MD, FSIR, FACR1 Address for correspondence Charles T. Burke, MD, FSIR, FACR, 101 Manning Drive, CB 7510 Chapel Hill, NC, 27599 (e-mail: charles_burke@med.unc.edu). Semin Intervent Radiol 2021;38:588–594 Since the first uterine artery embolization (UAE) procedures were performed by Ravina in 1995, UAE has become accepted as a safe and effective alternate method for the treatment of uterine fibroids.1–4 UAE is a minimally invasive method for treating fibroids and adenomyosis with shorter postoperative recovery times and faster returns to normal daily activities compared with hysterectomy.5 Even with a growth in its popularity, the number of UAEs performed to treat uterine fibroids compared with hysterectomies remains low.3,4 It has been postulated that one barrier to wider acceptance of UAE among providers and patients is the perception that post-UAE pain is severe and difficult to control.6 Pain is the most reported symptom associated with UAE with approximately 90% of patients experiencing some level of postoperative pain compared with 30% intraoperatively.3,7 Post-UAE pain can be accompanied by other symptoms including fever, nausea, vomiting, and malaise which has been termed “postembolization syndrome” (PES) and can be seen in up to 30 to 40% of patients postprocedurally.3,8,9 Both post-UAE pain and PES stem from inflammatory mediators released secondary to ischemia.3,8,9 The foundation of pain management for UAE involves managing pain at its various physiologic sites including the following: the reception/transmission of painful stimuli (local anesthesia, intrauterine arterial anesthesia, and nerve blocks), the production of inflammatory mediators (steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications), and the recognition of pain by the central nervous system (opiate analgesia).10 Although many periprocedural UAE pain management approaches and interventions have been proposed and studied, no consensus guidelines exist to date.11 Management styles between providers differ considerably and as such this article aims to serve as a guide for trainees through the various multimodal noninvasive and invasive approaches employed to prevent and treat peri-UAE pain. Issue Theme Advances in IR; Guest Editor, Charles T. Burke, MD, FSIR Preoperative Management Managing Expectations Preoperative pain management employs both patient periprocedural counseling and pharmaceutical prophylaxis. Post-UAE pain, which is centered in the lower abdominal and pelvic regions, is most severe within the first few hours postoperatively and usually peaks within the first 6 to 8 hours. This pain then slowly decreases over several hours before more rapidly decreasing within the next 24 hours. Over the next 2 to 3 days, the pain is usually of low level finally subsiding by 7 to 10 days.11–13 There have been attempts to predict a patient’s postprocedural pain severity using baseline uterine or fibroid volume; however, the results have not been significant.14 Managing patient expectations through preprocedural counseling on the time course and management of post-UAE pain can help better shape a patient’s understanding of their experience and may allay anxieties associated with the unexpected.6 Pharmaceutical Prophylaxis Pre-UAE pharmaceutical prophylaxis is aimed at prophylactically combating pain and nausea. Preprocedural prophylactic doses of long-acting antiemetics, anti-inflammatories, and steroids have been utilized to reduce periprocedural pain and nausea (►Table 1).6,15–17 Preprocedural regimens range from minimal to aggressive. A study published on the performance of UAE in the outpatient setting describes a more aggressive preprocedural regimen as follows: two doses of oral anti-inflammatory (naproxen: 1,000 mg), acid suppression (omeprazole: 20 mg to protect the gastric mucosa), antihistamine (hydroxyzine: 25 mg), and a stool softener medications the day before the procedure followed by IV analgesics (tramadol: 100 mg, metamizole: 2 g), IV acid suppressors (omeprazole: 20 mg), IV antiemetics (metoclopramide: 25 mg, droperidol: 0.10 mg), and an IV anti-inflammatory (piroxicam: 20 mg) medications just before the © 2021. Thieme. All rights reserved. Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, 18th Floor, New York, NY 10001, USA DOI https://doi.org/ 10.1055/s-0041-1739161. ISSN 0739-9529. Downloaded by: Albany Medical College. Copyrighted material. 588 Management of Postprocedural Uterine Artery Embolization Pain dural sedation with the goals of pain reduction, sedation, anxiolysis, amnesia, and motion control.18 Moderate sedation aims to safely generate a depression of consciousness with maintenance of response to verbal instruction, arousal upon tactile stimulation, patency of the airway, ventilatory drive, and cardiovascular function.19 Moderate sedation is commonly achieved with titrated IV doses of fentanyl and midazolam.18 In some patients, general anesthesia may be required; however, appropriate patient counseling, anesthesia evaluation, and patient selection are warranted. Local Anesthesia Injection of lidocaine at the vascular access site is essential to the management of localized pain, but it is often painful upon injection. Various injection techniques which have been shown to reduce pain associated with local lidocaine injection include pinching the skin at the injection site during injection, perpendicular needle entry, prioritizing slow subdermal and not intradermal injection, and preventing reinsertion of the needle in un-anesthetized regions when blocking a large area.20,21 The use of bicarbonate buffered lidocaine has also been shown to decrease the pain associated with the intradermal injection.6,22 Ultrasound-guided injection of tumescent anesthesia around the planned arteriotomy site is also important for reducing pain.6 procedure.16 Another study explored the use of a single dose of steroid (dexamethasone: 10 mg) compared with a control (normal saline) 1 hour before UAE along with a standard fentanyl patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) postprocedural pain control regimen. The two groups showed similar postprocedural pain medication use; however, serum inflammatory marker concentrations and pain scores at 12 and 24 hours were significantly lower in the dexamethasone group.15 Some providers advocate the use of preprocedural PCA (hydromorphone) with additional loading doses of analgesia shortly before the procedure along with preprocedural anti-inflammatories and antiemetics.6 Finally, managing preprocedural anxiety can also be aided with the use of oral benzodiazepines such as diazepam. Intraoperative Management Sedation Intraprocedural Management Moderate Sedation In the interventional radiology setting, moderate or conscious sedation is the mainstay method of achieving proce- 589 Intra-arterial Lidocaine Intra-arterial lidocaine has long been used for pain reduction in hepatic chemoembolization and peripheral arteriography and has since been applied to UAE with some efficacy.23 It is postulated that intra-arterial lidocaine has a local analgesic effect rather than a systemic effect. Due to lidocaine’s rapid onset and low toxicity, it has proven very useful and safe in this application.23 Although effective at controlling pain, a profound local vasospasm lasting approximately 10 to 20 minutes can occur.23,24 One prospective randomized controlled trial found that pain scores at 4 hours and narcotic use were significantly lower in the lidocaine groups injected during and after embolization compared with the control; however, the rate of complete infarction was decreased from 75 to 38.9% when lidocaine was injected during embolization (►Table 2).24 Similar findings were noted in another prospective control trial at 2 hours, but no significant difference was found beyond 2 hours (►Table 2).25 There is some heterogeneity in the literature concerning postembolization intra-arterial lidocaine injection with one prospective randomized control trial finding minimal to no significant difference between lidocaine and control groups (►Table 2).26 A recent systematic review of various articles studying the use of intraarterial anesthesia in hepatic embolization and UAE showed that it may slightly reduce the intensity of pain and amount of postprocedural opiates used, but their results were not significant prompting the call for further study on its efficacy (►Table 2).27 This technique is often favored by providers as it does not involve a second procedure and adds minimal time to the overall procedure. Seminars in Interventional Radiology Vol. 38 No. 5/2021 © 2021. Thieme. All rights reserved. Downloaded by: Albany Medical College. Copyrighted material. Table 1 Pre-procedure medications that can be used to reduce peri-procedure discomfort Pisanie et al. Management of Postprocedural Uterine Artery Embolization Pain Pisanie et al. Table 2 Comparison of study outcomes related to intraprocedural pain management techniques/protocols Study (study type) Comparison (group designation) Outcome Pain or opiate value comparison (no. of patients (n), p-value) Noel-Lamy et al24 (prospective randomized) Intra-arterial lidocaine during UAE (A) vs. Intra-arterial lidocaine after UAE (B) vs. Control (C) Postprocedural pain at 4 h and opiate use were decreased in groups A and B. More incomplete fibroid necrosis in A Mean pain at 4 h A: 28.6 B: 35.8 C: 59.4 (n ¼ 60, p ¼ 0.001) Duvnjak and Andersen25 (prospective randomized) Intra-arterial lidocaine after UAE (A) vs. Control (B) Postprocedural pain at 2 h and opiate use were decreased in group A Mean pain at 2 h A: 42.7 B: 61.1 (n ¼ 40, p 0.02) Katsumori et al26 (retrospective review) Intra-arterial lidocaine after UAE (A) vs. Control (B) No significant reductions in pain or opiate use between the groups Mean pain at 3 h A: 2.2 B: 2.9 (n ¼ 100, p ¼ 0.07) Intra-arterial lidocaine Superior hypogastric nerve block Yoon et al13 (prospective randomized) SHNB (A) vs. Sham procedure (B) Postprocedural pain was significantly decreased in group A immediately after UAE but not upon arrival at PACU or beyond. Opiate and antiemetic use was decreased in group A Mean pain immediately after UAE A: 1.0 B: 2.6 (n ¼ 44, p ¼ 0.01) Park et al31 (retrospective review) SHNB (A) vs. No SHNB (B) Postprocedural opiate use was decreased in group A Mean postprocedural morphine use A: 35.9 mg B: 51.7 mg (n ¼ 88, p ¼ 0.08) Embolic agent and embolization techniques Bilhim et al32 (prospective randomized) Initial 500–700 µm particles in UAE (A) vs. Initial 350–500 µm particles in UAE (B) Postprocedural morphine use was decreased in group A. No difference in decrease in size of uterus and dominant leiomyoma or clinical outcomes Mean pain UAE (during, after) A: 0.97, 3.42 B: 1.44, 4.71 (n ¼ 160, p ¼ 0.03, p 0.0001) Spies et al34 (prospective randomized) UAE with PVA particles (A) vs. UAE with tris-acryl gelatin microspheres (B) No difference in pain severity, frequency of incompletely infarcted fibroids, symptom improvement, or patient satisfaction between groups Maximum pain score after UAE A: 3.1 B: 3.0 (n ¼ 100, p ¼ 0.87) Han et al33 (prospective randomized) UAE with PVA particles (A) vs. UAE with tris-acryl gelatin microspheres (B) No difference in pain severity fentanyl use, and incompletely infarcted fibroids. Group A had higher occurrence of transient uterine ischemia and rescue analgesia Mean pain score during first 24 h A: 7.0 B: 7.3 (n ¼ 54, p ¼ 0.55) Unilateral UAE (A) vs. Bilateral UAE (B) Mean maximum pain score, morphine dose, and fluoroscopy time were decreased in group A Mean maximum pain score A: 3.7 B: 5.7 (n ¼ 56, p ¼ 0.03) Unilateral UAE Stall et al36 (case–control) Abbreviations: PACU, post-anesthesia care unit; PVA, polyvinyl alcohol; SHNB, superior hypogastric nerve block; UAE, uterine artery embolization. Seminars in Interventional Radiology Vol. 38 No. 5/2021 © 2021. Thieme. All rights reserved. Downloaded by: Albany Medical College. Copyrighted material. 590 Management of Postprocedural Uterine Artery Embolization Pain Pisanie et al. 591 Superior Hypogastric Nerve Block The superior hypogastric nerve plexus (SHNP) innervates the uterus, bladder, and other pelvic structures in females and as such has been a favorable target for controlling pain in patients undergoing pelvic procedures and with pelvic cancer–related pain.28 The SHNP lies just anterior and inferior to the aortic bifurcation in the retroperitoneum in around 83% of patients with the remaining lying superior to the bifurcation based on cadaveric studies.28 A superior hypogastric nerve block (SHNB) with local anesthesia is commonly performed under fluoroscopic guidance with a 15-degree craniocaudal tilt. A catheter at the aortic bifurcation and the L5 vertebral body act as targets for injection. A 21- or 22gauge 15- or 20-cm Chiba needle is inserted 2 to 5 cm below the umbilicus and advanced to the anterior surface of the L4 or L5 vertebral body below the aortic bifurcation. Lack of blood aspiration, the injection of contrast, and lateral views can help confirm extravascular positioning. Local anesthesia (10 mL ropivacaine 0.75% or 20 mL bupivacaine 0.5%) mixed with a small volume of contrast is injected under fluoroscopic guidance with intermittent aspiration. Mild systemic analgesia and an antibiotic (3 g IV ampicillin/sulbactam) are also given before the procedure (►Fig. 1).3,29 The addition to overall procedure time is also minimal at around 8 to 10 minutes.10 The addition of 40 mg of triamcinolone can also prolong SHNB analgesia from around 8 to 10 hours (as is commonly reported) to 33.8 hours.29 Although SHNB has been shown to be less effective at reducing pain relative to epidural anesthesia, a recent double-blind randomized control trial showed SHNB to significantly lower mean postprocedural pain scores immediately after UAE, opiate use, and antiemetics with no major complications as compared with a sham procedure.13,30 Of note, pain reduction compared with the sham procedure was not significant on arrival at the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), or at departure from the PACU (►Table 2).13 Finally, SHNB was also shown to decrease the amount of post-procedural morphine used when compared with no SHNB by 47.2% (►Table 2).31 Embolic Agent and Embolization Techniques Choice of embolic agent and embolization techniques has been shown to affect postoperative UAE pain levels. In comparing the size of embolic particles used, one study found that the initial use of small PVA particles (350– 500 μm) as compared with larger particles (500–700 μm) resulted in significantly higher mean pain scores at 4 to 8 hours with similar postprocedural results (►Table 2).32 In assessing the relationship between commonly used embolic agents and postoperative pain scores, studies have shown that there is no significant difference between nonspherical PVA particles when compared with tris-acryl gelatin microspheres (►Table 2).33,34 A final important factor to assess is embolization technique. Although no randomized control trials have been conducted, the commonly accepted angiographic embolization endpoint of choice to reducing postprocedural pain is a “pruned-tree” appearance of the uterine vasculature. The fibroid vessels are “pruned” off by the embolization and there remains slow uterine artery flow characterized by remnant contrast within the vessel at five heartbeats.3,6,35 The physiologic rationale behind this endpoint is that this near-stasis within the uterine artery will allow partial recanalization preventing myometrial ischemia and thus a decrease in postoperative pain.35 Unilateral UAE in Select Patients Some authors have explored the efficacy of unilateral UAE in select patients to reduce embolization of normal myometrium; however, it is also thought that this may decrease efficacy of the UAE, as collaterals from the contralateral artery could maintain supply.36,37 One retrospective trial found that only embolizing the ipsilateral uterine artery in patients with unilateral disease (fibroids only supplied by a single uterine artery on preprocedural imaging and intraprocedural angiography) can significantly reduce postprocedural pain and radiation dose with similar patient satisfaction, fibroid infarction rate, and symptom resolution as compared with standard bilateral UAE (►Table 2).36 Postoperative Management Although postprocedural management varies, many previously studied protocols utilize some combination of opioids nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) acetaminophen at the core of their pain control regimen. A recent systematic review of the literature concerning post- Seminars in Interventional Radiology Vol. 38 No. 5/2021 © 2021. Thieme. All rights reserved. Downloaded by: Albany Medical College. Copyrighted material. Fig. 1 Intraprocedural fluoroscopy images of superior hypogastric nerve block: (a) Digital subtraction aortogram of the aortic bifurcation (arrow). (b) Needle (arrow) is directed toward the L4 vertebral body just below the region of the aortic bifurcation. (c) Lateral view of the lumbar spine showing extravascular contrast (arrow) pooling anterior to the L4 vertebral body. Arrowhead—needle. (d) Extravascular contrast (arrow) is noted to pool in the region of the L4 vertebral body around the level of the aortic bifurcation. Management of Postprocedural Uterine Artery Embolization Pain UAE pain control protocols compared the mean maximum postprocedural pain scores between 26 different studies with a total of 3,353 patients. The analysis splits the postprocedural pain regimens into four different groups which all included opioids NSAIDs acetaminophen with no additional therapy (16 studies, 2,632 patients), SHNB (4 studies, 313 patients), intra-arterial lidocaine (3 studies, 238 patients), and other (steroids, ketamine, or α2 adrenergic receptor agonists; 3 studies 170 patients). When comparing mean maximal pain scores of the four groups, the authors found no significant difference, concluding that opioids NSAIDs acetaminophen may be adequate in controlling pain post-UFE. However, the authors also note that there is large heterogeneity in the included studies and that more investigation is needed.11 Patient-Controlled Analgesia Some providers incorporate PCA into their regimens as an effective opiate-based method for controlling pain.6 Although effective, opiate PCA is associated with nausea, drowsiness, and constipation prompting some providers to employ more local methods of pain control such as SHNB, which has been shown to decrease the need for PCA.38 Many studies have been conducted analyzing variations on medications in the PCA regimen and its effect on post-UAE pain. A prospective nonrandomized trial showed that morphine PCA was superior to fentanyl PCA at controlling pain with the possibility of increased nausea.39 Another study found that the addition of dexmedetomidine to a fentanyl PCA may also decreased the need for fentanyl.40 Interestingly, the above describe systematic review of the literature on post-UAE pain treatment performed a subgroup analysis of the four groups studied and compared the same groups now including the variable of PCA or no PCA. The analysis showed that the addition of PCA did significantly decrease pain in patients in the included studies; however, it again noted that further analysis is needed to support these findings.11 IV Nonopiate Analgesia Due to the side effects associated with opiate medications including nausea, drowsiness, itching, constipation, and respiratory depression, there has been move toward multimodal pain control regimens. The nausea experienced by some patients may make it difficult to deliver oral medications and as such some providers utilize IV NSAIDS and acetaminophen to help ensure a sustained multimodal regimen. One double-blind randomized control trial studied the effect of four different pain regimens on post-UAE pain and nausea: IV acetaminophen 1 g, IV ibuprofen 800 mg, IV acetaminophen þ IV ibuprofen, and IV ketorolac 30 mg given prior to the procedure and every 6 hours up to 24 hours along with hydromorphone IV PCA. The study showed that the IV acetaminophen þ ibuprofen group provided similar pain control with less opiate use compared with the ketorolac group (28.09 mg compared with 40.33 mg of morphine equivalents); however, there was more nausea experienced in the IV acetaminophen/ibuprofen group.41 Seminars in Interventional Radiology Vol. 38 No. 5/2021 Pisanie et al. Discharge Medications Discharge medications rely on over-the-counter options such as NSAIDs and acetaminophen with the addition of oral opiate analgesia (oxycodone 5 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg) for break through pain. Antiemetics and stool softeners are also commonly provided.6 Conclusion Although no consensus guidelines exist to date, a breadth of literature exists exploring a wide variety of multimodal approaches to managing and controlling post-UAE pain. With the knowledge of the literature, trainees can tailor pain control regimens which best suit their own practice style and skillset as well as better modulate therapy on an individual basis to provide adequate and safe post-UAE pain control for their patients. References 1 Ravina JH, Herbreteau D, Ciraru-Vigneron N, et al. Arterial emboli- sation to treat uterine myomata. Lancet 1995;346(8976):671–672 2 Narayanan S, Gonzalez A, Echenique A, Mohan P. Nationwide 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 analysis of hospital characteristics, demographics, and cost of uterine fibroid embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017;28(02):S48 Kohi MP, Spies JB. Updates on uterine artery embolization. Semin Intervent Radiol 2018;35(01):48–55 Pron G, Bennett J, Common A, Wall J, Asch M, Sniderman KOntario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Collaboration Group. The Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Trial. Part 2. Uterine fibroid reduction and symptom relief after uterine artery embolization for fibroids. Fertil Steril 2003;79(01):120–127 Hehenkamp WJK, Volkers NA, Birnie E, Reekers JA, Ankum WM. Pain and return to daily activities after uterine artery embolization and hysterectomy in the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: results from the randomized EMMY trial. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2006;29(02):179–187 Spencer EB, Stratil P, Mizones H. Clinical and periprocedural pain management for uterine artery embolization. Semin Intervent Radiol 2013;30(04):354–363 Pron G, Mocarski E, Bennett J, et al; Ontario UFE Collaborative Group. Tolerance, hospital stay, and recovery after uterine artery embolization for fibroids: the Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2003;14(10):1243–1250 Goodwin SC, McLucas B, Lee M, et al. Uterine artery embolization for the treatment of uterine leiomyomata midterm results. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1999;10(09):1159–1165 Ganguli S, Faintuch S, Salazar GM, Rabkin DJ. Postembolization syndrome: changes in white blood cell counts immediately after uterine artery embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;19(03): 443–445 Rasuli P, Jolly EE, Hammond I, et al. Superior hypogastric nerve block for pain control in outpatient uterine artery embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004;15(12):1423–1429 Saibudeen A, Makris GC, Elzein A, et al. Pain management protocols during uterine fibroid embolisation: a systematic review of the evidence. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2019;42(12):1663–1677 Basile A, Rebonato A, Failla G, et al. Early post-procedural patients compliance and VAS after UAE through transradial versus transfemoral approach: preliminary results. Radiol Med (Torino) 2018; 123(11):885–889 Yoon J, Valenti D, Muchantef K, et al. Superior hypogastric nerve block as post-uterine artery embolization analgesia: a randomized and double-blind clinical trial. Radiology 2018;289(01): 248–254 © 2021. Thieme. All rights reserved. Downloaded by: Albany Medical College. Copyrighted material. 592 14 Roth AR, Spies JB, Walsh SM, Wood BJ, Gomez-Jorge J, Levy EB. 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Pain after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata: can its severity be predicted and does severity predict outcome? J Vasc Interv Radiol 2000;11(08):1047–1052 Kim SY, Koo BN, Shin CS, Ban M, Han K, Kim MD. The effects of single-dose dexamethasone on inflammatory response and pain after uterine artery embolisation for symptomatic fibroids or adenomyosis: a randomised controlled study. BJOG 2016;123 (04):580–587 Pisco JM, Bilhim T, Duarte M, Santos D. Management of uterine artery embolization for fibroids as an outpatient procedure. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2009;20(06):730–735 Bilhim T, Pisco JM. The role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) in the management of the post-embolization symptoms after uterine artery embolization. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2010;3(06):1729–1738 Martin ML, Lennox PH. Sedation and analgesia in the interventional radiology department. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2003;14(9, Pt 1):1119–1128 Tuite C, Rosenberg EJ. Sedation and analgesia in interventional radiology. Semin Intervent Radiol 2005;22(02):114–120 Fosko SW, Gibney MD, Harrison B. Repetitive pinching of the skin during lidocaine infiltration reduces patient discomfort. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;39(01):74–78 Strazar AR, Leynes PG, Lalonde DH. Minimizing the pain of local anesthesia injection. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;132(03):675–684 Hanna MN, Elhassan A, Veloso PM, et al. Efficacy of bicarbonate in decreasing pain on intradermal injection of local anesthetics: a meta-analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009;34(02):122–125 Keyoung JA, Levy EB, Roth AR, Gomez-Jorge J, Chang TC, Spies JB. Intraarterial lidocaine for pain control after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2001;12(09): 1065–1069 Noel-Lamy M, Tan KT, Simons ME, Sniderman KW, Mironov O, Rajan DK. Intraarterial lidocaine for pain control in uterine artery embolization: a prospective, randomized study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017;28(01):16–22 Duvnjak S, Andersen PE. Intra-arterial lidocaine administration during uterine fibroid embolization to reduce the immediate postoperative pain: a prospective randomized study. CVIR Endovasc 2020;3(01):10 Katsumori T, Miura H, Yoshikawa T, Seri S, Kotera Y, Asato A. Intraarterial lidocaine administration for anesthesia after uterine artery embolization with trisacryl gelatin microspheres for leiomyoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2020;31(01):114–120 Shiwani TH, Shiwani H. Intra-arterial anaesthetics for pain control in arterial embolisation procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CVIR Endovasc 2021;4(01):6 Eid S, Iwanaga J, Chapman JR, Oskouian RJ, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. Superior hypogastric plexus and its surgical implications during spine surgery: a review. World Neurosurg 2018;120:163–167 Stewart JK, Patetta MA, Burke CT. Superior hypogastric nerve block for pain control after uterine artery embolization: effect of 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Pisanie et al. addition of steroids on analgesia. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2020;31 (06):1005–1009.e1 Malouhi A, Aschenbach R, Erbe A, et al. Effectiveness of superior hypogastric plexus block for pain control compared to epidural anesthesia in women requiring uterine artery embolization for the treatment of uterine fibroids - a retrospective evaluation. RoFo Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Nuklearmed 2021;193(03): 289–297 Park PJ, Kokabi N, Nadendla P, Lindsey T, Dariushnia SR. Efficacy of intraprocedural superior hypogastric nerve block in reduction of postuterine artery embolization narcotic analgesia use. Can Assoc Radiol J 2020;71(01):75–80 Bilhim T, Pisco JM, Duarte M, Oliveira AG. Polyvinyl alcohol particle size for uterine artery embolization: a prospective randomized study of initial use of 350-500 μm particles versus initial use of 500-700 μm particles. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22(01): 21–27 Han K, Kim SY, Kim HJ, et al. Nonspherical polyvinyl alcohol particles versus tris-acryl microspheres: randomized controlled trial comparing pain after uterine artery embolization for symptomatic fibroids. Radiology 2021;298(02):458–465 Spies JB, Allison S, Flick P, et al. Polyvinyl alcohol particles and trisacryl gelatin microspheres for uterine artery embolization for leiomyomas: results of a randomized comparative study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004;15(08):793–800 Spies JB. Recovery after uterine artery embolization: understanding and managing short-term outcomes. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2003;14(10):1219–1222 Stall L, Lee J, McCullough M, Nsrouli-Maktabi H, Spies JB. Effectiveness of elective unilateral uterine artery embolization: a casecontrol study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22(05):716–722 Bratby MJ, Hussain FF, Walker WJ. Outcomes after unilateral uterine artery embolization: a retrospective review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008;31(02):254–259 Pereira K, Morel-Ovalle LM, Wiemken TL, et al. Intraprocedural superior hypogastric nerve block allows same-day discharge following uterine artery embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2020;31(03):388–392 Kim HS, Czuczman GJ, Nicholson WK, Pham LD, Richman JM. Pain levels within 24 hours after UFE: a comparison of morphine and fentanyl patient-controlled analgesia. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008;31(06):1100–1107 Kim SY, Chang CH, Lee JS, Kim YJ, Kim MD, Han DW. Comparison of the efficacy of dexmedetomidine plus fentanyl patient-controlled analgesia with fentanyl patient-controlled analgesia for pain control in uterine artery embolization for symptomatic fibroid tumors or adenomyosis: a prospective, randomized study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24(06):779–786 Hoffman CH, Jahr JS, Kim GJ, et al. Reducing post procedural pain and opioid consumption using IV acetaminophen and IV ibuprofen following uterine fibroid embolization: a prospective, double blind, randomized controlled study. J Imaging Interv Radiol 2018; 01(01):1–6 Seminars in Interventional Radiology Vol. 38 No. 5/2021 © 2021. Thieme. All rights reserved. 593 Downloaded by: Albany Medical College. Copyrighted material. Management of Postprocedural Uterine Artery Embolization Pain