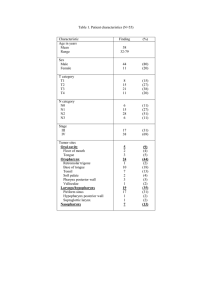

Original Article Congenital Trismus Secondary to Masseteric Fibrous Bands: A 7-Year Follow-Up Report as an Approach to Management Adrian M. Skinner, MBChB Martin J. W. Rees, FRACS Auckland, New Zealand A 7-year prospective follow-up report, which was previously presented in this journal as an initial pediatric case report, is presented as an approach to management of congenital trismus secondary to masseteric fibrous bands. Adams and Rees discussed management, including endoscopic exploration at 18 months of age with early recurrence of trismus. Under the care of the same plastic surgeon and his team, the progress of this patient over 7 years has given us an insight into management. The cause of trismus is not fully elucidated, but the condition can result in compromised caloric intake, speech development, facial appearance, dental care, and oral hygiene. The decreased oral opening may be secondary to shortening of the muscles of mastication, which may cause tension moulding and distortion of the coronoid process; yet, there is no consensus on the optimal management of temporomandibular joint trismus and all its causes. The patient presented in this report, now aged 7 years, has proceeded through to open surgery on two occasions yet, regrettably, has persistently tight masseter muscles and only 8 mm of jaw opening. Key Words: Congenital trismus, pseudocamptodactyly syndrome, masseteric fibrous bands T rismus, derived from the Greek trimos meaning “grating” or “grinding,” is an inability to open the mouth.1 It involves tonic contraction of jaw-closing muscles and is a symptom either of general disease affecting nerves or joints or of local disease leading to reduced mouth From the Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Department, Middlemore Hospital, Counties Manukau District Health Board, Otahuhu, Auckland, New Zealand. Address correspondence to Mr Rees, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Department, Middlemore Hospital, Counties Manukau District Health Board, Otahuhu, Auckland, New Zealand; e-mail: MRees@middlemore.co.nz. opening.2 The normal range of maximal mouth opening in adults, measured as the interincisal distance, varies within a range of 40 to 60 mm,1 although a lower limit of 23 mm and an upper limit of 68 mm are reported.3 Variations reflect age and sex.4 In general, males display greater mouth opening.5 The etiology of trismus includes infection, trauma, dental treatment, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, and congenital problems.1 The differential diagnosis of congenital trismus includes interalveolar synechiae most commonly,6 TMJ bony ankylosis,2 distal arthrogryposes,7,8 Hecht syndrome,9,10 and abnormalities of the muscles of mastication.11 Clinical Management The patient we discuss presented with profound congenital trismus with associated impaired feeding and sucking. 11 In addition, she had evidence of a “floppy” neck, a tendency to arch her back on crying, minor outpouching of the upper esophagus, increased tone in the anterior left leg compartment muscles, shortened leg muscles, and ocular motor dyspraxia. The pterygomandibular raphe was noted to be tight on both sides, with associated masseteric spasticity. Computed tomography showed no evidence of bony fusion, and magnetic resonance imaging was reported as normal. When she presented for endoscopic-assisted exploration at 18 months of age, the interincisal distance was measured at 4 mm actively and 12 mm passively. Under general anesthesia, mouth opening was measured at 20 mm. During this procedure, tight fibrous bands on the anterior surface of the masseter muscles were identified and released, resulting in 30 mm of opening. Histological findings confirmed the presence of fibrous tissue along with muscle atrophy. Unfortunately, trismus recurred 3 months after surgery, with early relapse noted at 6 weeks. At 29 months after this early procedure, or at 3 years of age, jaw opening was measured at 8 mm. This was preventing dental impressions for creating spring-loaded plates for jaw physiotherapy. Food 709 THE JOURNAL OF CRANIOFACIAL SURGERY / VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5 September 2004 chewing was also a problem. In addition, although the patient was developing language and speech ability, she was noted to be not fully intelligible. Neurodevelopmentally, she was reported as making good progress at about 6 months behind her peers. At 43 months after her initial endoscopic procedure, shortly after turning 5 years of age, the patient’s jaw opening was measured at 5 to 6 mm. Five months later, she proceeded to surgery under general anesthesia in an attempt to free up this limited opening. An incision was made in the upper buccal sulcus on both sides of the mouth taken laterally just outside the pterygomandibular raphe. Access was then gained to the lateral border of the coronoid process; from there, the deep surface of the masseter muscle on each side was dissected, including the outer surface. There were some small fibrous bands in each muscle that were divided, but this made no difference to jaw opening. The stiffness of the jaw was quite profound, and it appeared to be ankylosed because of fibrosis around the TMJs, which were free at the previous procedure. Unexpectedly, apart from some minor masseteric bands, these bands had not reformed. Ten units Clostridium botulinum type A toxin (Botox) and 0.4 ml saline were injected in four positions into each masseter muscle through the intraoral incision. Incisions were closed with interrupted 5/0 absorbable sutures. Fig 1 Muscles involved in congenital trismus. M (masseter): T (temporalis): MPt (Medial Pterygoid). The endoscope was introduced in two places (a) deep to the upper pole of the ear, thence deep to the deep temporal fascia, and (b) through the buccal mucosa lateral to the pterygomandibular raphe anterior to the coronoid process of the mandible. Fibrous bands were seen in the anterior border of the masseter, medial pterygoid and the temporalis. The latter looked normal but there were bands to the underside of the maxillary buttress and zygomatic arch which were divided ‘blind’ after dividing the masseteric and pterygoid bands under direct vision. Release of all three bands on each side permitted the jaw to be fully opened. 710 After a further 5 months, the patient proceeded to further surgery, again under general anesthesia, to open release of fibrosis scarring subsequent to previous findings. An incision was made in front of the coronoid process and vertical ramus of the mandible, taking it down to the lateral aspect of the angle of the mandible. The masseter muscles were freed up from the lateral surface of the mandible right down to their insertion on the angle of the mandible on both sides, allowing an additional 10 mm of jaw opening. A further dissection of fibrous scarring around the pterygomandibular raphe gave a little extra movement. The coronoid processes were then traced up into the infratemporal fossa, and further fibrosis in this area was released. Then, by exerting pressure on the mandible, it suddenly came free as some of the residual fibrosis tissue gave way, resulting in a 40mm opening. Botox was then used to paralyze the masseter, medial pterygoid, and temporalis muscles, with 10 U being injected into both masseters and both medial pterygoids and 5 U into each temporalis muscle in its anterior part, leaving the posterior part for some weak closure. Finally, dental impressions were taken to make dental models and splints to protect the patient’s teeth when using a Therabyte to help maintain jaw opening. The patient’s family moved, and she was seen by a pediatrician at 61⁄2 years of age. At this stage, baseline jaw opening was noted to have decreased to 15 mm, with an increase to 18 mm achieved via Therabyte. Although still allowing for an electric toothbrush, it was noted that the patient was choking on food of a “more lumpy consistency.” Language was reported to be good and even above average for the patient’s age in spite of some intermittent staccato delivery of speech. At this stage, daily Therabyte was still being applied to maintain or improve jaw opening. Nevertheless, it should be noted that although jaw opening was being sustained after surgery with the use of the Therabyte initially, this first Therabyte broke, with a resulting delay of at least 3 weeks before replacement. During this stage, the amount of jaw movement was reported by the patient’s parents to decrease significantly, and they were subsequently unable to recover this movement. At 7 years of age, the patient was referred back to her original plastic surgical consultant for followup. Jaw opening was now reported to be disappointing at only 8 mm. Her parents were no longer able to use a normal-sized toothbrush for teeth cleaning and were using a “cut-down” modified toothbrush. In addition, the patient was now unable to chew her food adequately. This may also have been caused by a muscular coordination problem with her tongue CONGENITAL TRISMUS / Skinner and Rees and cheeks, probably attributable to her syndrome. On examination, the masseter muscles were noted to be tight again, despite use of Botox at the previous surgery. The patient was again noted to be slightly delayed for her age developmentally. At this stage, further Botox treatment is under consideration. In addition, the patient is undergoing tongue exercises with a speech therapist to improve chewing. She will continue to be followed up. DISCUSSION his is an interesting case of trismus in a patient with presumed sporadic trismus-pseudocamptodactyly syndrome. Lefaivre and Aitchison12 note that only two cases of pediatric patients with this syndrome who have proceeded to surgery are reported in the literature. Trismus-pseudocamptodactyly, or Hecht, Hecht-Beals, or Hecht-Beals-Wilson syndrome, a rare autosomal dominant condition with variable penetrance, is a disorder of muscle development and function involving short muscle and tendon units that limit range of motion.12 The most consistent feature of this syndrome is trismus, but upper and lower extremities are affected also.13 Not all deformities are present in each affected person, with limited mouth opening and pseudocamptodactyly occurring most frequently.14 Trismus presents the most serious threat to these individuals, with resulting compromise to caloric intake, speech development, facial appearance, and dental care and oral hygiene.1,13 In addition, intubation can be difficult and hazardous.15,16 Affected individuals have been reported to take twice the usual time to consume a meal.9 Some infants are unable to accept a conventional rubber nipple between their gums,17 and tonsillectomy is difficult.17 Furthermore, general anesthesia does not relieve the trismus.17,18 It is noted, however, that in old age, affected individuals have a larger mouth opening, thereby allowing dentures to be worn, perhaps because of resorption and remodeling of the mandible.17 The cause of trismus is not fully elucidated. No radiographic evidence of abnormality of the TMJs has been found.9,17,19,20 De Jong21 suggested the presence of an abnormal maxillomandibular ligament. Ter Haar and Van Hoof20,22 described enlargement of the coronoid process confirmed radiologically. This same abnormality was noted by Mabry et al,17 but unlike Ter Haar and Van Hoof,20,22 they found no correlation between extent of coronoid enlargement and degree of limited movement. They suggested that decreased opening may be secondary to T shortening of the muscles of mastication, particularly of the temporalis, which could cause tension moulding and distortion of the coronoid process. They note that in pronounced cases of trismus, the coronoid process is enlarged by extensive pull of the temporalis muscle tendon unit, which decreases mandibular excursion.20 In turn, the enlarged coronoid process impinges on the body of the zygomatic bone and inner margin of the arch, explaining limited mandibular excursion.23 The most frequently reported upper extremity abnormality involves pseudocamptodactyly, which presents as a bending of the fingers on dorsiflexion at the wrist because of shortening of the flexor tendonmuscle unit.14 Unlike camptodactyly, this deformity is neither fixed nor progressive.13 Children may crawl on clenched fists with their weight resting on the knuckles.17 About 5% of affected individuals have foot and leg problems.17 Lower extremity anomalies may include short hamstring muscles, short gastrocnemius and hamstring muscles with associated pelvic tilt, talipes equinovarus, “clubfeet,” “hammer toes,” metatarsus varus, and calcaneovalgus deformity.13,17 Other deformities have also been noted. Stature is reduced in some individuals, although they are normally proportioned.4 Others have reported prognathism,10 blepharochalasis,21,24 a quilted appearance of the cheeks,21 ptosis,17 and micrognathia.14 Our patient, although displaying no clear evidence of the typical autosomal dominant inheritance pattern or of pseudocamptodactyly, does have evidence of trismus with normal radiological findings with shortened leg muscles. There is some similarity to this case with the presentation of a 53-year-old female patient with this syndrome described by Mercuri,24 as noted previously by Adams and Rees.11 Several features of the syndrome, including trismus and pseudocamptodactyly, were noted at the time of this woman’s dental surgery, and she proceeded to open surgery, during which fibrous bands found bilaterally anterior to the masseter muscles were cut and reported as consistent with tendon. Her family history is unavailable, however. Adams and Rees11 also note some lesser similarities to a patient presenting with arthrogryposis congenita multiplex type II subtype E (a syndrome of sporadic inheritance characterized by a distinctive hand abnormality, trismus, other contractures, short stature, micrognathia, webbed duck scoliosis, and mental retardation).8 There is no consensus on the optimal management of TMJ ankylosis in this patient population. Lefaivre and Aitchison12 recently presented the case of a 28-month-old boy with trismus-pseudocampto711 THE JOURNAL OF CRANIOFACIAL SURGERY / VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5 September 2004 dactyly syndrome and a limited mouth opening of 6 mm whose initial treatment involved an open surgical approach after no improvement with jaw physiotherapy. This patient underwent extensive subperiosteal dissection of the mandible, bilateral coronoidectomy (because of bilateral impingement on the zygomatic arch), and TMJ exploration. An initial intraoperative opening of 18 mm was achieved, although mouth opening decreased to 12 mm in the weeks immediately after surgery. This was corrected with physical therapy, and 1 year after surgery, the authors report a successful outcome with active mouth opening at 25 mm. They also note that the patient’s father, who was diagnosed with the same syndrome, displayed a similar range of motion without surgery. Follow-up of our patient and of the patient presented by Lefaivre and Aitchison12 will be interesting. In addition to the relapse after the endoscopic procedure in our patient, other authors have described progressive relapse after correction.14,15 It is interesting to note that Lefaivre and Aitchison12 have attributed the absence of relapse in their patient to continuous jaw physiotherapy independent of surgical technique. They note that long-term therapy may be the most important variable affecting long-term outcome and advise waiting until cooperation is optimal to avoid otherwise necessary intervention. Hirano et al6 also note the importance of postoperative manipulation after initial surgery in achieving normal mouth opening, especially because the TMJ may have been restricted in its movement during the fetal period.25–27 Markus4 operated on a 23-year-old man with a mouth opening of 11 mm, which increased to 30 mm after bilateral coronoidectomy and was measured at 27 mm at 2 years of follow-up. He also attributed sustaining mouth opening to compliance with postoperative therapy. This is interesting, because the patient we present here was initially unable to comply at a young age with physiotherapy and splinting initiated after the endoscopic procedure. In addition, her jaw opening decreased after subsequent open surgery while waiting 3 weeks for a replacement Therabyte. CONCLUSION t is interesting to note the different approaches to management of trismus in the pediatric population. We present a patient who initially underwent an endoscopic procedure at 18 months of age but, subsequently, has required two open surgical procedures. Lefaivre and Aitchison12 present the case of a patient, also in the pediatric population, who under- I 712 went initial open surgical procedure at 28 months of age. There are advantages associated with both procedures. From reviewing these two cases, it is clear that although the early endoscopic approach may allow minimally invasive access,28 decreased scarring, less postoperative pain, shortened hospital stay, and earlier rehabilitation,11 the early open approach may allow for avoidance of the early relapse described in our patient and also for stability of correction.12 Subsequent open surgery at 5 years of age in the patient presented has also, unfortunately, resulted in relapse. The management of future additional cases and follow-up of the two pediatric cases reported to date will hopefully provide some answers to the complex and interesting issue of care for patients with trismus. In any case, compliance with therapy and optimal age for surgery seem to be important considerations. REFERENCES 1. Dhanrajani PJ, Jonaidel O. Trismus: aetiology, differential diagnosis and treatment. Dent Update 2002;29:88–94 2. Poulsen P. Restricted mandibular opening (trismus). J Laryngol Otol 1984;98:1111–1114 3. Nevakari K. ‘Elipsio prearticularis’ of the temporomandibular joint. A pantomographic study of the so-called physiological subluxation. Acta Odontol Scand 1960;18:123 4. Markus AF. Limited mouth opening and shortened flexor muscle-tendon units: ‘trismus-pseudocamptodactyly.’ Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1986;23:137–142 5. Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, LeResche L, et al. Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders: clinical signs in cases and controls. J Am Dent Assoc 1990;120:273–281 6. Hirano A, Iio Y, Murakami R, et al. Recurrent trismus: twentyyear follow-up result. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1994;31:309–312 7. Hall JG, Reed SD, Greene G. The distal arthrogryposes: delineation of new entities—review and nosologic discussion. Am J Med Genet 1982;11:185–239 8. Reiss J, Sheffield L. Distal arthrogryposis type II: a family with varying congenital abnormalities. Am J Med Genet 1986;24: 255–267 9. Hecht F, Beals RK. Inability to open the mouth fully: an autosomal dominant phenotype with facultative camptodactyly and short stature. Birth Defects Orig Art Ser 1969;V:96–98 10. Wilson RV, Gaines DL, Brooks A, et al. Autosomal dominant inheritance of shortening of the flexor profundus muscletendon unit with limitation of jaw excursion. Birth Defects Orig Art Ser 1969;V:99–102 11. Adams C, Rees M. Congenital trismus secondary to masseteric fibrous bands: endoscopically assisted exploration. J Craniofac Surg 1999;10:375–379 12. Lefaivre J-F, Aitchison MJ. Surgical correction of trismus in a child with Hecht syndrome. Ann Plast Surg 2003;50:310–314 13. O’Brien PJ, Gropper PT, Tredwell SJ, et al. Orthopaedic aspects of the trismus pseudocamptodactyly syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop 1984;4:469–471 14. Yamashita DD, Arnet GF. Trismus-pseudocamptodactyly syndrome. J Oral Surg 1980;38:625–630 15. Seavello J, Hammer GB. Tracheal intubation in a child with trismus pseudocamptodactyly (Hecht) syndrome. J Clin Anesth 1999;11:254–256 16. Nagata O, Tateoka A, Shiro R, et al. Anaesthetic management CONGENITAL TRISMUS / Skinner and Rees 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. of two paediatric patients with Hecht-Beals syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth 1999;9:444–447 Mabry CC, Barnett IS, Hutcheson MW, et al. Trismus pseudocamptodactyly syndrome: Dutch-Kentucky syndrome. J Pediatr 1974;85:503–508 Lano CF, Jr, Werkhaven J. Airway management in a patient with Hecht’s syndrome. South Med J 1997;90:1241–1243 Horowitz SL, McNulty EC, Chabora AJ. Limited intermaxillary opening—an inherited trait. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1973;36:490 Ter Haar BGA, Van Hoof RF. The trismus-pseudocamptodactyly syndrome. J Med Genet 1974;11:41 De Jong JGY. A family showing strongly reduced ability to open the mouth and limitation of some movements of the extremities. Humangenetik 1971;13:210–217 Ter Haar BGA, Van Hoof RF. Trismus also onderdeel van enkele weinig bekende syndromen. Maandsschrift voor Kindergeneeskunde 1973;41:180 23. Van Hoof RF. Enlargement of the coronoid process with special reference to the trismus-pseudocamptodactyly syndrome (family studies by Dr B. G. A. Ter Haar). Tandheelkundige Monografiee XIV. Leiden, Stafleu: An Tholen BV, 1973:1–120 (Dutch translated by F. G. Hardman) 24. Mercuri LG. The Hecht, Beals and Wilson syndrome: report of a case. J Oral Surg 1981;39:53–56 25. Miskinyar SAC. Congenital mandibulo-maxillary fusion. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992;29:89–91 26. Randall P. Discussion of Verdi GD and O’Neal B. Cleft palate and congenital alveolar synechia syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg 1983;74:686 27. Sternberg N, Sagher U, Golan J, et al. Congenital fusion of the gums with bilateral fusion of the temporomandibular joints. Plast Reconstr Surg 1983;72:385–387 28. Vasconez L, Core G, Oslin B. Endoscopy in plastic surgery: an overview. Clin Plast Surg 1995;22:585–589 713