Consensus Government -Principles of Team Leadership in Nunavut Canada

advertisement

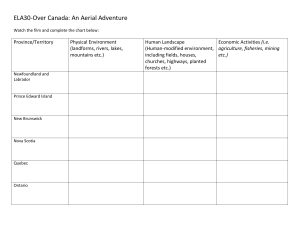

CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT: What does the Nunavut Model teach us about Leadership? Pria Ranganath Providence School of Transformative Leadership and Spirituality, Saint-Paul University HUM 5101: Leadership Theory and Practice Dr. Michael Seguin December 17, 2021 CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Table of Contents Origin of Research ........................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction: ........................................................................................................................................... 4 The Topic: ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Essay or Literary review? ......................................................................................................................... 5 Clarifications ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Context ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Consensus Government in Canada ................................................................................................. 6 Background: ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Consensus Government and Nunavut ...................................................................................................... 6 How does the Consensus Model work? .................................................................................................... 7 A Note on the Process ..................................................................................................................... 8 Please see Appendix A ............................................................................................................................. 8 Research Questions ......................................................................................................................... 8 What does Nunavut’s Consensus Government teach us about democracy? ............................................... 8 What is the difference between “Leadership-by-election” and “leadership by appointment? ..................... 8 What is “consent-of the-governed,” and why does this matter? ................................................................ 9 How does democracy fit in? ..................................................................................................................... 9 Leadership Theories, Approaches and Models ............................................................................... 9 Skills and Traits ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Behaviour, Situational, LMX and Path-Goal Method ............................................................................... 10 Authentic and Adaptive ......................................................................................................................... 11 Team Leadership ................................................................................................................................... 11 Followership: ........................................................................................................................................ 12 Was it Transformative? ......................................................................................................................... 12 How does it contribute to Scholarship? ........................................................................................ 13 Inclusion and Leadership ....................................................................................................................... 14 Where did influence originate? .............................................................................................................. 14 Importance of context: .......................................................................................................................... 15 Democracy in Leadership: ...................................................................................................................... 15 Addressing Criticisms:............................................................................................................................ 16 What are some implications for practice? .................................................................................... 17 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................... 17 BIBLIOGRAPHY .............................................................................................................................. 19 CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT APPENDIX A ................................................................................................................................... 22 Birth of a Nation - Nunavut - 1999 .......................................................................................................... 23 Location and Context............................................................................................................................. 25 Inuit Homeland: .................................................................................................................................... 25 History (1725-1921 A.D)......................................................................................................................... 26 Population (2021) .................................................................................................................................. 27 Constituencies and Party-system ........................................................................................................... 28 Representation in Legislature ................................................................................................................ 29 APPENDIX B ................................................................................................................................... 30 A Note on the process ........................................................................................................................... 31 Methodology used: ............................................................................................................................... 31 Literature Review .................................................................................................................................. 31 Interviews:............................................................................................................................................ 33 APPENDIX C ................................................................................................................................... 34 A note on Power and Hierarchy ............................................................................................................. 35 CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Origin of Research Introduction: On 25th Oct 2021, the territory of Nunavut in Canada officially elected its 6th Legislative assembly of representatives from 22 constituencies spread across the region. All Nunavummiut residents cast their vote in what was seen as an even balance of new community members and veteran members of the Legislative Assembly or MLAs. (S. F. CBC News, 2021) What was remarkable in this provincial election was the governance model followed in Nunavut. It differs from all of the other provinces and territories in Canada 1 since the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut is one of only two federal, provincial or territorial legislatures in Canada that has a “consensus style of government” rather than the more common Westminster system of party politics (CG | Government of Nunavut, n.d.). The creation of Nunavut was a landmark moment in the evolution of Canada. It showcased Inuit leadership in what has been a significant development in the history of the world’s Indigenous people. (Amagoalik, 2007) The Topic: This study, much like the model, originated from an awareness of the urgent need for transformative leadership in the political arena, especially in the resurrection of democracy and was the result of a chance conversation2 had in Oct 2021 with a person of Indigenous ancestry3. I hope this paper serves to increase scholarly interest in the working of the Consensus Model of government and serves the greater purpose of attracting emerging scholars of Indigenous origin and to the decolonization of scholarship through 1 Except NWT, which also follows a Consensus style Governance model. 2 For more information on how this topic came about and originated, refer to Appendix A. 3 For more details, please refer to the List of Interviewees in Appendix C CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Essay or Literary review? This paper is structured as an essay, although it incorporates and includes various references from leadership theories and practices from HUM 5101 course material and other reference materials 4 throughout the document. Clarifications: Since the Consensus Model was developed as a reflection and representation of Indigenous values and ways, and it would be amiss to talk about Consensus Government without touching on the process and people who informed and shaped it. And so, although this paper concerns itself primarily with the study CG model of governance, it includes discussion and examples of Inuk Leadership where appropriate5 because of the representative nature of the CG model in keeping with Indigenous values and culture. Context So, what is Consensus Government (or CG)? Consensus Government is a governance model of political leadership practiced as an alternative to the Westminster style of governance. It is a non-partisan democracy most closely embodied in countries such as Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Lebanon, Sweden, Iraq, and Belgium 6, where consensus is an essential feature of political culture, mainly to prevent any one linguistic or cultural group from political 4 For those interested in learning more about this topic, I provide a list of references in Appendix B 5 Since this is still an emerging area of scholarship, I refer primarily to the example of John Amagoalik, known as the “Father of Nunavut,” who was an Inuk from Nunavik (Québec) and made a significant contribution to the creation of Nunavut. For a more comprehensive discussion on Inuit leadership, kindly refer to the section on Influence. 6 I include the Wikipedia definition here first before getting into more scholastic definitions CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT domination. It is distinct that the Cabinet is elected by the Legislature without reference to political parties, unlike more conventional models. Consensus Government in Canada Background: Nunavut is one of Canada’s three territories. Northwest Territories and Nunatsiavut7 being the other two. (Appendix A). While the Consensus form of Government is practiced in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories in Canada, the Nunavut model is different and a more independent and improved version of the NWT model. The Nunavut model was modified to be freer of its restrictions and has the advantage of being developed from scratch. It is considered by many as more representative of Indigenous values and processes to date. While Consensus Government, in general, or CG is defined as a variation of the standard model of responsible government” (O’Brien, 2003), the Nunavut model is an experiment in selfrepresentative government (Amagoalik, 2007) (Jull, 1992) facilitated by the Inuit. It is an alternative model that situates Indigenous values of consensus decision making within a Westminster-framework (White, 2006) (Campbell, 2016). Consensus Government and Nunavut Nunavut (which means "our land.” covers an area of over 2 million sq km and accounts for roughly 20% of Canada's landmass and over 50% of Canada's coastal region, approximately the size of western Europe. ((Hicks & White, 2015) p.6 It represents 35,000 Nunavummiut; the people of Nunavut spread across over 22 communities, twelve of which have fewer than 1000 7 An autonomous area of Indigenous occupation in Newfoundland and Labrador CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT residents. One of the unique challenges of Northern communities is their remoteness. They are disconnected from land routes (Appendix A), compounding a series of challenges common to remote and dispersed communities. (NWT Bureau of Statistics, n.d.) The Consensus Government in Nunavut came into existence on 1 April 1999. Nunavut’s 22 constituencies (Appendix A) are spread over its vast area that constitutes 1/5 of Canada’s landmass. Members from each constituency stand and are elected as Independents without party affiliation—elected members from the Lower House or the “Legislative Assembly” (Appendix A). The October 2021 Elections in Nunavut saw the election of 22 MLA’s to the Legislative Assembly from each constituency, which in turn elected 11 members amongst themselves, including a Premier and a Speaker of the House. (Nunavut, n.d.-b)8 (David Gunn & Steven Silcox, Jane Sponagle, 2017)(CBC News, 2021) (Tranter, 2021)(Appendix A) How does the Consensus Model work? In Nunavut, the model takes a participatory or consensus approach to leadership, allowing a more direct path to the Legislative Assembly using the direct election from each constituency. This makes it different from the more standard Westminster model of “party” politics. Cabinet members are nominated and require Legislative member support and ballot before the election to Cabinet in a process that protects both confidentialities of members and the public need for transparency. (See Appendix A, B) Power is thus retained in the lower house (Tranter, 2021). and bills are passed by the Legislature, which breaks into “caucus” or “committees” to debate, discuss, and decide specific issues like Health, Community services and Infrastructure, 8 For those desiring to learn more about the functioning of this governance model, there exist some excellent sources, many of which have been included in the Bibliography, as also the Government of Nunavut’s website: CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT etc. Meanwhile, essential decisions continue to be made through election or ballot, first in the Lower house and then in the cabinet, which holds 11 and 9 members, with the Commissioner being responsible for giving assent to the bills on the advice of the Premier. While the Premier can assign specific portfolios to his Ministers, he is still answerable to the Legislative Assembly and MLA’s and thereby the communities represented, another point of difference which will be discussed in greater detail further in this paper. A Note on the Process Please see Appendix A Research Questions What does Nunavut’s Consensus Government teach us about democracy? I analyze the Nunavut model with a view towards what lessons in leadership it offers us. I further divide the above question into three other questions and proceed as follows What is the difference between “Leadership-by-election” and “leadership by appointment? This “leadership-by-election “of the Legislative Assembly described above in the Nunavut model results in three important outcomes: it empowers the assembly, increases their sense of ownership in the outcome, and brings an element of “choice” into the equation. This makes it easier for the assembly to work within a framework of their choosing, thereby promoting improved team adhesion and leadership engagement. (Uhl-Bien 2014, N 366) (Lipman-Blumen 2005, N. p.369). A salient feature of the CG model is its participatory decision-making approaches, which is seen as an improvement over the standard model. CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT What is “consent-of the-governed,” and why does this matter? In Nunavut, all Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) are elected as independent candidates. This keeps with how Inuit have traditionally made decisions often involving community nominations and endorsement especially seen in the value placed in elders., When a community “chooses” its leadership, it is allowed to use its informal knowledge to decern what might be in its own best interest. The Nunavut model provides a more natural approach to community representation at the territorial level. I argue that choice matters and plays a vital role. One cornerstone of democracy and freedom is choice—field(Locke & Shapiro, 2003). Leadership is unsustainable without the “consent of the governed” since leaders require follower support and confidence to lead. (Burns, 1979) (Northouse, 2022b) (Shields, 2018a) How does democracy fit in? Canada is a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy in that its executive authority is vested formally in the Queen through the Constitution. Every act of government is carried out in the name of the Crown, but the accountability for those acts rests with the Canadian people. While there are differences in the Westminster and CG models of provincial governance, the common factor is that both are deeply committed to representative democracy and the notion of “responsible government.” Leadership Theories, Approaches and Models Leadership is often conceptualized in multiple ways (Burns, 1979)(Northouse, 2022)(Shields, 2018)(Scharmer, 2007), rending it impossible to classify in neat and orderly categories, with the current state of scholarship calling for greater cognizance and synergies. CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT (Clark & Harrison, 2017). Attached below is an attempt to evaluate the Nunavut CG model against some more prevalent leadership theories. (Northouse, 2022) Skills and Traits The CG model, in many ways, is a reflection of Indigenous values and preferences. (Jull, 1992) (Amagoalik, 2007) (Hicks & White, 2015) (Scharmer, 2007). It is, in some ways, a representation of its people, as also Inuk leadership, which contrary to conventional leadership theories, was modest and unassuming, and we never see abusing any privilege. Inuit community prioritizes relationships, and it is perhaps no surprise that in the Oct 2021 elections, the Inuit valued connections to community and heritage over some of the more conventional traits of looks, height, education, experience, fluency etc. (Nunavut Voters Head to the Polls Monday in 6th General Election | CBC News, n.d.) Behaviour, Situational, LMX and Path-Goal Method In many ways, the Nunavut model results from a process of navigation through complex challenges set in a profoundly relational context. Therefore, I argue that this presents many examples of community leadership in Behaviour and Situational contexts. For example, we see Inuk representation in acting ethically and deciding to postpone CG negotiations even if to their detriment to make time to involve the community more fully (Jull, 1992)(White, 2006)(Amagoalik, 2007), thereby showcasing situational and ethical leadership While the behavioural approach prescribes directive leadership as a practical approach to ambiguous tasks, I argue that this was not the case for the Inuit, whose early experience of Federal administration left them unsatisfied, disillusioned and in some instances worse off than before with regards to CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT the ambiguity of land rights and ownership issues. (Northouse, 2022c) (Joseph, n.d.) Contrasting this with the LMX framework of In-and-Out-Groups, we see how the process for CG and the Inuit community largely emerged out of an “out-group” experience with the early relationship between settlers and the Inuit, affecting aspects of their trust, respect, obligations and even emotions to date. Authentic and Adaptive Aspects There is a vital authenticity element to the CG model in the transparency of the process that led to its creation. Adaptable leadership is represented through Inuk leaders like John Amagoalik who have reflected Inuit values of openness, inclusion, and trust throughout the process. We see how critical incidents (Northouse, 2022)(Shields, 2018), such as residential school experience and the extermination of husky population experiences, shaped their struggle in powerful and unexpected ways. We also see the leadership of those like John Amagoalik taking a “balcony view,” supporting people in their adaptative journeys of coming to terms with “extinguishable rights” and educating the community and teaching them of the value of self-governance. Team Leadership We see how the CG model extensively uses the principle of lateral decision making (N.p.463) and how this affects inclusion and participation in group processes. The CG model shows leanings towards “heterarchy” (Aime, Humphrey DeRue & Paul 2014) in its functioning, and this speaks to shifting power in teams and how this can lead to improved positive outcomes. A proof of this shift is the recent election of Nunavut’s premier. This shift in elected choice reflected changing demographics and preference for youth representation and came out of a CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT lateral decision-making structure. (CBC · 2021) (White, 2006) The Nunavut model also offers additional opportunities to advance and inform emerging scholarship in the area of Team and Group Leadership, Followership: We are aware of the role of followers in getting the job done (Carsten et al. 2014) and the vital relational component of Followership (Uhl-Bien 2014, N 366). When leadership does not emerge from or is removed from or is not representative of the led- population, sometimes there is a difference between leaders’ interpretation of needs and real needs. (Lipman-Blumen 2005, N. p.369) For example, in the case of Nunavut, Federal leaders framed follower priorities primarily around safety and inclusion while followers identified recognition of rights, equal access to employment and cultural representation. (Jull, 1992) (Amagoalik, 2007) (GOC ESDC, 2018). Similarly, youth representatives identified access to computer and leadership training, while the government has yet to assist with the issue of internet access and equitable supplies. (NWT Bureau of Statistics, n.d.) Was it Transformative? There are different ways to evaluate the transformative aspects of the CG journey. (Northouse, 2022). Previous scholars of Transformative work (Burns 1978, Bass 1985, Bennis and Nanus 1985, 2007, Kouzes and Posner 2002, 2017) have highlighted aspects of Transformational. Leadership is when the community is engaged and collectively exercised and is non-partition (Bass and Riggio 2006). We also know that it is built on a common identity and offers followers (or participants) a more direct path towards participation in the decision-making (Tranter, 2021). CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT We are reminded of leadership that comes out of followership and includes the raising of morality in others (Burns, 1979), while also consistently emphasizing the collective good (Northouse, 2022d) (Shields, 2018b). We are reminded that transformative leadership seeks to include not merely transactional (cash for land). (Amagoalik, 2007) (Bass & Steidlmeier 1999 ) Howell & Avolio) but also continued interest in the welfare of the community (Shields, 2018b). then, In summary, the creation of the Nunavut model showcases an authentic and adaptable trajectory that gains momentum and traction both within and outside of the community (even if much later). Inuk leadership emerges out of this process and serves as a reflection of closely held community beliefs, values, and traits. We see the collective influence in the creation of a product or model and how this articulates a people’s vision. CG model offers living proof that an alternate leadership model for political governance exists and that it is possible to have a government both by and for the people. The Nunavut model serves as an example of how marginalized people can overcome odds and engage in transformative self-representation without alienating others and promote cultural preservation in peaceful yet powerful ways. How does it contribute to Scholarship? So, in what ways does the study of the CG model in Nunavut add to the already existing body of scholarship? It makes a significant contribution by extending the boundary of underresearched aspects of Team Leadership and Followership while also informing the theoretical frameworks of LMX theory, Path-Goal Method, Authentic and Adaptable Leadership as well as and other participatory approaches. It specifically contributes to the dialogue of decision-making in Group or Team settings where conventional models have resulted in poor or unsatisfactory outcomes by showing us how the sum of the parts can be better leveraged in service of the whole. CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Inclusion and Leadership The CG process offers us tangible proof that the most significant push for inclusion of Indigenous representation comes not always from leadership appointments but from those excluded and overlooked. This has also been noted by other scholars (Jull, 1992) (Wilson, 2016). This shifts the paradigm by placing the “setting of direction” or “leadership” not on one individual leader but on the collective, as a way of transforming the whole.9 Where did influence originate? The CG model shows us that influence evolved from the followership in response to challenges that the leadership framework was unable to address in previous years satisfactorily. Leadership scholarship reminds us that calls for ‘leadership’ have often arisen due to moral, social, political and economic trends or events deemed problematic. (Wilson, 2016) ‘Leadership,’ whatever form it may take, has been repeatedly proffered as a solution to matters that are understood as troublesome, threatening, and needing fixing. I argue that the impetus for change came from within the community. Be it Charlie Watt, co-chair of ICNI who played a central role in the selfdetermination struggle, Mark Gordon of Makivik Corporation, who was responsible for the 1982 constitution amendment 35(3) concerning land claims and "treaty rights" or Zebedee Nungak from Nunavik and John Amagoalik from Nunavut who met when representing at the three first ministers conference on Aboriginal Constitution Rights in 1884-87, (Marc Malone and 9 1 Corinthian 12:15-20 “as it is there are many parts, but one body.” CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Carole Levesque, 1994) (Amagoalik, 2007) influence and leadership in case of Nunavut rose from the bottom10. Importance of context: It is essential to recall Shield’s observation and admonition in the taking on models without a critical understanding of context at this junction. It would do good for us to remember that the NWT government (unlike Nunavut) failed and alienated indigenous peoples precisely because it took on southern models uncritically. Nunavut should continue not to repeat this mistake, and there is a continued need for scholarship to ensure this. (C. M. · C. CBC News, 2017)(Shields, 2018a)(Scharmer, 2007) (Jull, 1992) Democracy in Leadership: When we return to the original definition of the word “Democracy,” we notice how its translation from its Greek and Athenian roots translate as “demos,” meaning “people” and “Kratos,” meaning “rule” or “power,” reminding us again of a government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation either directly (direct democracy) or through the choice of representative governing officials (representative democracy), which is precisely what the CG model is set up to do. 10 All these examples offer significant opportunities for further research. CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Source: Online definition, Wikipedia, accessed 9 Dec2021 Addressing Criticisms: While it is impossible to address all criticisms within the scope of this paper, this is an attempt to address the most significant one that is often levelled against the Inuit community. This one emerged in the interview process in response to a question that solicited honesty and a settler perspective. When asked about what (in their opinion) constituted the most significant criticism of the Inuk experiment, I was then informed long-term Pond Inlet resident11 of their still “livingoff hand-outs.” I have a threefold response to this, the most important one being that the Inuit population’s journey has been to claim back what was rightfully theirs and to reframe this as a hand-out is erroneous. Framing it this way typifies precisely the kind of “deficit thinking” that Shields warns us against (Shields, 2018). Secondly, the Inuit population pay 3 to 5 times the base tax rate of other provinces for sustenance supplies while settling for reduced investment in infrastructure (land access is still non-existent, as is clean water, proper housing, schools, and health care, all of which continue to be challenges to this day). Third, the Nunavut is no different from other provinces like Quebec, which still rely on and benefit from equalization payments, except that Nunavut is more inclusive of outsiders and religiously and linguistically tolerant. 11 Known through association with faith-group. See Appendix for a List of Interviews conducted. CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT What are some implications for practice? There are various lessons that we can glean from our observations. The Nunavut model raises an important question – that of viewing leadership as something that originates from hierarchically superior people. (p.127) The journey of the Inuit towards self-determination has shown us that, often, influence came not from those with titles or in positions of power, but that locusts of force or inspired action came from the community, i.e., the followership. The CG model supports this kind of influence by setting up a direct path to democracy through election by geography/ jurisdiction since the process of standing for election is a simple one and through community nomination. Following a “leadership-by-election” model of government incorporates inclusion and sets up a precedent for a more participant-led style approach to democratic decision-making. This truth has important implications for group leadership processes, as also other team processes, including faith groups, corporations, working groups and other team processes in an increasingly VUCA world where all are required to lead from the future. Conclusion So how does all this fit together? What and how does this impact us? CG model shows us that change is possible when viewed through the lens of oppression and injustice, by offering a blueprint in how this journey can evolve, offering hope and promise. We also see how marginalized peoples can, in a single generation, overcome barriers of physical isolation, distance, lack of economic development, alien language and culture, discreet racism, neglect, and sullen derailments by well-placed officials to gain political recognition and self- CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT government in their ancient homeland (Jull, 1992), offering hope to those who find themselves stuck in similar situations of under-representation and disempowerment. It shows us how upholding democratic values such as" leadership by-election" doesn't have to come from an “established” leadership hierarchy (although it could, and probably should) but from the follower community and helps redirect value and scholarship to where it truly belongs. Additionally, the model shows us a direct path to democracy instead of " leadership by appointment" which was designed by and for power retention in the upper hierarchical realms. It helps us understand the importance of the “consent of the governed” by reminding us that leadership cannot exist without the support and confidence of the “led”. So, do we take this to mean that Nunavut’s CG is perfect or assures all of what has been intended? By no means since it is still an experiment in progress. Just as a well-designed house is only one part of the equation and does not automatically translate into a home, it will take conscious and sustained action to ensure its continued success. There is still room for the furthering of scholarship with regards to the inner workings of the consensus model to continue to learn what works and what needs to be improved. My hope is that this paper inspires a cohort of new emerging leadership scholars who will be able to move the scholarship forward and address some of the gaps that team leadership and participatory processes present. I believe that the Consensus model of Government in Nunavut can hold transformative power if we let it, both for our personal journeys aa also for participatory processes in leadership. In a world that is rapidly witnessing the death of democratic leadership and a desperate need for inspirational and CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT credible examples, we have the Inuit to thank for their formidable example of representative leadership and for showing the rest of Canada and the world how to also get there. BIBLIOGRAPHY Amagoalik, J. (2007). Changing the face of Canada: The life story of John Amagoalik. Nunavut Arctic College. Burns, J. M. (1979). Leadership. Harper & Row. Campbell, A. (2016). Made in Nunavut: An Experiment in Decentralized Government, by Jack Hicks and Graham White. Artic. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311248308_Made_in_Nunavut_An_Experiment_in_D ecentralized_Government_by_Jack_Hicks_and_Graham_White CBC News, C. M. · C. (2017, October 26). Why this political science professor says a consensus government wouldn’t fly on P.E.I. | CBC News. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/prince-edward-island/pei-politics-government-parties1.4592900 CBC News, S. F. (2021, October 25). Nunavut’s new government sees even split of newcomers and returning MLAs | CBC News. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/nunavut-election-2021-results-1.6224306 Consensus Government | Government of Nunavut. (n.d.). Retrieved October 19, 2021, from https://www.gov.nu.ca/consensus-government David Gunn & Steven Silcox, Jane Sponagle. (2017). What is Consensus Government? [Vedio]. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1082027075674 Govt. of Canada ESDC. (2018). Nunavut: Inuit Labor Force Analysis Report. HRSDC- CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT RHDCC.gc.ca. canada.ca/publicentre-ESDC Hicks, J., & White, G. (2015). Made in Nunavut: An Experiment in Decentralized Government. UBC Press. Joseph, B. (n.d.). The Red Paper: A Counterpunch to the White Paper. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/the-red-paper-a-counter-punch-to-the-white-paper Jull, P. (1992). An Aboriginal Northern Territory: Creating Canada’s Nunavut, North Australia Research Unit. Locke, J., & Shapiro, I. (2003). Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration. Yale University Press. Marc Malone and Carole Levesque. (1994). Nunavik Government (Paper FE 05/05/95). Royal Commission on Aboriginal People. Northouse, P. G. (2022a). Adaptive Leadership. In Leadership Theory and Practice Ninth Edition (9th Edition, p. p.285-321). SAGE Publications, Inc. Northouse, P. G. (2022b). Authentic Leadership, In Leadership Theory and Practice (9th Edition, p. p.221-251). SAGE Publications, Inc. Northouse, P. G. (2022c). Leadership: Theory and practice (Ninth edition.). SAGE Publications, Inc. Northouse, P. G. (2022d). Path-Goal Theory. In Leadership Theory and Practice Ninth Edition (9th edition, p. p.132-156). SAGE Publications, Inc. Nunavut, G. of. (n.d.). What is Consensus Government? Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories [Public Service]. Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories. Retrieved November 19, 2021, from https://www.ntassembly.ca/visitors/what-consensus Nunavut voters head to the polls Monday in 6th general election | CBC News. (n.d.). CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/nunavut-votes-oct-25-1.6221101 NWT Bureau of Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved November 16, 2021, from https://www.statsnwt.ca/ O’Brien, K. (2003). Some thoughts on Consensus Govt in Nunavut. Canadian Parliamentary Review, 26(No.4). http://www.revparl.ca/english/issue.asp?param=60&art=26 Scharmer, C. O. (2007). Addressing the Blind Spot of Our Time. Society for Organizational Learning. Shields, C. M. (2018a). Changing Knowledge Frameworks to Promote Equity. In Transformative leadership in education: Equitable and socially just change in an uncertain and complex world (2nd Edition, p. p.28-46). Routledge. Shields, C. M. (2018b). Fostering Democracy and Global Citizenship: Understanding Justice and Interconnectedness in our Global Community. In Transformative leadership in education: Equitable and socially just change in an uncertain and complex world (2nd Edition). Routledge. Unofficial elections results | Elections Nunavut. (n.d.). https://www.elections.nu.ca/en/2021-territorial-election White, G. (2006). Traditional aboriginal values in a Westminster parliament: The legislative assembly of Nunavut. Journal of Legislative Studies, 12(1), 8–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330500483930a Wilson, S. (2016). Questioning Leadership Knowledge. Edward Elgar Publishing. CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT APPENDIX A CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Birth of a Nation - Nunavut - 1999 Nunavut’s CG came into operation on 1 April 1999 Image Source CBC News TV Broadcast Nunavut Elections: 25 October 202 CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Location CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Connection to the South- land routes: Source CBC Location and Context Inuit Homeland: Source: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT History (1725-1921 A.D) CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT CANADA'S POPULATION up more than half a million people (+531,497). 37.6 million The largest annual growth in history. JULY 1 2019 on July 1, 2019, Canada's population growth rate was also the highest among all G7 countries. Demographic growth 2018/2019 +1.4% Canada +0.6% Y.T. > 1.7 % (2021) Nvt. -0.3% N.W.T. +1.4% B.C. +1.6% Alta. +1.0% Sask. -0.8% N.L. +1.2% Man. +1.7% Ont. +1.2% Que. +2.2% P.E.I. +0.8% N.B. higher than Canada lower than Canada +1.2% N.S. Same as Canada International migration was the main driver of population growth over the last year. On July 1, 2019, there were 6,592,611 Canadians aged 65 and over. For the first time, baby-boomers make up the majority (51%) of seniors. Factors of growth in 2018/2019: Temporary and permanent immigration. More than 10,000 centenarians in Canada. Because of increased life expectancy, the number of centenarians (10,795) has grown very fast in recent years. 82% Natural increase (difference between the number of births and deaths). 18% © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Industry, 2019 Source: Annual Demographic Estimates: Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2019. www.statcan.gc.ca Population (2021) Catalogue number: 11-627-M | ISBN: 978-0-660-32195-0 CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Constituencies and Party-system Spread of 22 Constituencies in NU. Source: CBC News TV Broadcast 2017 CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Representation in Legislature CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT APPENDIX B CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT A Note on the process Methodology used: The process followed in the completion of this paper follows the Research Ethics Board (REB) and Research Integrity, ASA -412 REB and the stipulations thereof. This work is also situated within the Responsible Conduct of Research commitment that St Paul’s University undertook on March 28th, 2018. Given the higher standard of International Best Practices in humanitarian relief, a voluntary commitment has been made to the SPHERE 2020 9 Edition benchmark, which mandates the “no harm” principle. The tutorial TCPS 2: Course on Research Ethics (CORE) and Module 9, Research involving First Nations, Inuit, and Metis people of Canada12 have been completed and all University Instructions on the subject were followed on and up to 14 Dec 2021. Literature Review Attached are some additional recommendations for those interested in learning more about Consensus Government and/ or its workings: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/nunavut-votes-oct-25-1.6221101 https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/elections/nunavut/2021/results/ https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/nunavut-votes-oct-25-1.6221101 https://www.elections.nu.ca/en/2021-territorial-election https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/nunavut-election-2021-results-1.6224306 TV Broadcast: https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1082027075674 https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/prince-edward-island/pei-politics-government-parties1.4592900 12 For those desiring to learn more, these links provide more information: https://ustpaul.ca/uploadfiles/AdminGov/ASA/en/ASA-412_Research_Ethics_Board.pdf, https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/education_tutorialdidacticiel.html and https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/research-recherche_module9.html CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Recommended Readings: Dec 2021 1. Creating Canada’s Nunavut – Peter Jull 2. Changing the Face of Canada – John Amagoalik 3. Made in Nunavut – An Experiment in Decentralized Government – Jack Hicks and Graham White 4. Some thoughts on the CG in Nunavut – Kevin O’Brien, Canadian Parliamentary Review http://www.revparl.ca/english/issue.asp?param=60&art=26 5. Nunavik Government – Marc Malone and Carole Levesque (Paper presented as part of a research program of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People (October 1994) 6. Government of Nunavut website: https://www.gov.nu.ca/consensus-government 7. What is CG: https://www.ntassembly.ca/visitors/what-consensus Image credits: macmedia.ca CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT Interviews: Since the scope of this work was restricted to that of a term paper in size and time, the interview component was limited to 7 people (see Appendix B), some of which were conducted remotely due to Covid and when possible, in-person, following safety regulations. Due to limited scope, an REB clearance application for community-based work was informed as unnecessary. All those interviewed were happy to share their experiences and offered valuable insights, and I owe much to their support and kindness. Any faults or miscommunication is the authors alone. CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT APPENDIX C CONSENSUS GOVERNMENT IN NUNAVUT A note on Power and Hierarchy There is a correlation between power and colonial thinking and the systems and frameworks that came out of this era. Colonialism is defined as the “practise or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, generally with the aim of economic dominance. Power is defined as the capacity or ability to direct or influence the behaviour of others or the course of events. Research has shown us that when this power is reduced, it enables further follower participation. (Laccharo, Rittman & Marks p.26) There is a correlation between influence and power in that power is influence, no matter where its origin. We have also seen how influence stemmed from the community in the Inuit journey and found representation through Inuit Leadership. And therefore, by correlation, we see how power did as well rest within the Inuk people and learn of how it was handled. Leadership, at least in the external sense with its title, hierarchy, and perks in the old colonial model, still refers to upper hierarchy. This shows us how Leadership without its core of influence can end up being merely a shell of what it purports to be. The CG model fixes this one errant feature of the Westminster model by redirecting power to where it truly belongs- to the Legislative assembly and then by extension, to its people. • Due to technical reasons, the Comparison Sheet evaluating the two models (Nunavut’s CG vs more Standard) has been separately enclosed as an attachment.