AfP Snapshot-of-Adaptive-Management-in-Peacebuilding-Programs

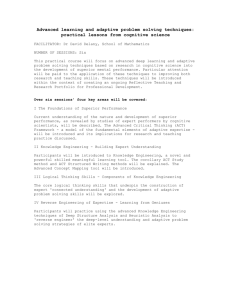

advertisement