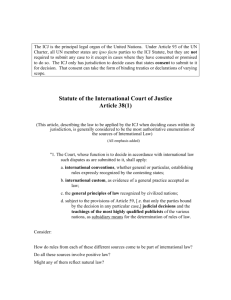

Department of Law Formative Coursework Cover Sheet This form MUST be completed and submitted as the front page of any non-assessed coursework submitted to the Department of Law – coursework without a suitable coursework cover may not be passed on to the correct member of staff for marking. Student ID: 210764521 Student Name: Charles D'Haene Module code: LAW6032 Module Title: Public International Law Tutor Group: 2 Tutor name: P. OKOWA Word Count: 2995 Read the following statement carefully and sign below: I hereby confirm that the submitted document represents my own work in all respects, except in so far as is indicated either in the text or in the footnotes; and that I have acknowledged by express reference any use of material derived in whole or in part from any other published source. Signature of student: QUEEN MARY UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW ACADEMIC YEAR: 2021-2022 To what extent are the sources in article 38(1) of the ICJ statute to be applied in a hierarchical order? A critical examination of the role of hierarchy in the doctrine of sources in international law. Professor: P. OKOWA Formative Assessment submitted by Charles D'HAENE ii Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER I. SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW .................................................... 2 SECTION I. MATERIAL SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW .......................................................... 2 SECTION II. FORMAL SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW............................................................. 2 §1. Article 38 (1) of the ICJ Statute ...................................................................................... 2 A. Treaty law .................................................................................................................... 3 B. Customary law ............................................................................................................. 3 §2. Peremptory norms ........................................................................................................... 3 §3. Soft law ............................................................................................................................ 4 CHAPTER II. IS THERE HIERARCHY BETWEEN THE SOURCES IN ARTICLE 38 (1)? .................................................................................................................................................... 4 CONCLUSION......................................................................................................................... 7 iii INTRODUCTION 1. The question of the hierarchy of sources in international law is an important one, and definitely not as easy as one might think at first sight. In domestic law, the question where law derives its content and authority from is rarely asked as the answer is usually quite straight forward. The primary source of law is usually the legislature. Aside from that, the government can make secondary law and law can also be established over the years by decisions by courts.1 2. International law on the other hand, derives it authority from more than one source, so it is not uncommon for certain obligations to derive their authority from different sources. This is not always a problem as these different norms don't necessarily conflict. They may contain the same obligation and thus they can easily coexist. The real problem occours when two different sources contain conflicting obligations. The question then is: Which source prevails over the other? And does it prevail every time or does it vary from case to case? 3. In this short assessment I will examine this question as thoroughly as the word limit allows me to. First I will define what exactly a source of international law is, which types of sources there are and where article 38 (1) ICJ Statute comes into play. Afterwards I will attempt to answer the question whether article 38 (1) ICJ Statute does in fact contain a hierarchy of sources. In a conclusion I will then wrap up all of my findings. To come to this conclusion I have done a literature review where I closely examine various sources from different authors such as THIRLWAY, PELLET, HERNANDEZ, WOUTERS and SHAW. 1 H. THIRLWAY, Sources of International Law, Oxford University Press, 2019, 2. 1 4. CHAPTER I. SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW SECTION I. MATERIAL SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 5. Material sources of international law are those sources that are not legally binding on itself but do provide evidence of existence consensus among states and thus of a legally binding rule.2 These sources can be found in various places such as judgments from international courts, a textbook or a resolution by a political organ. BESSON even argues that moral and social processes such as power play, cultural conflicts and ideological tensions should be included in the definition of material sources of international law.3 SECTION II. FORMAL SOURCES OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 6. Formal sources of international law are the methods used to create rules of general application. These rules of general application are binding on their addressees and are the source from which a legal rule derives its legal validity.4 The term might be deemed misleading as it seems to be associated with the manner in which domestic legal orders make laws and the constitutional machinery of law in which that happens. In international law this constitutional system does not exist. Instead, international law is solely made by consent or acceptance. §1. Article 38 (1) of the ICJ Statute 7. International law has many enumerations of sources of international law. The most prominent of these enumerations can be found in article 38 (1) of the ICJ Statute. It lists the formally recognized sources of international law. This article stipulates that: The Court, whose function is to decide in accordance with international law such disputes as are submitted to it, shall apply: a. international conventions, whether general or particular, establishing rules expressly recognized by the contesting states; b. international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law; c. the general principles of law recognized by civilized nations; 2 J. CRAWFORD, Brownlie's Principles of Public International Law (Ninth Edition), OUP, 2019, 18-19; G. HERNANDEZ, International Law (1st Edition), OUP, 2019, 32; A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 864; H. THIRLWAY, Sources of International Law, Oxford University Press, 2019, 6. 3 S. BESSON, "Theorising the Sources of International Law" in S. BESSON and J. TASIOULAS (eds.), The Philosophy of International Law, OUP, 163. 4 J. CRAWFORD, Brownlie's Principles of Public International Law (Ninth Edition), OUP, 2019, 18-19; G. HERNANDEZ, International Law (1st Edition), OUP, 2019, 32; R. JENNINGS and A. WATTS, Oppenheim's International Law, Ninth Edition, Longman, 1996, 23; A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 864. 2 d. subject to the provisions of Article 59, judicial decisions and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations, as subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law. 8. This enumeration is a list of four formal, recognized sources of law. Treaty law, customary law, general principles of law and judicial decision and teachings of qualified publicists. 9. Even though this stipulation is quite old, as it stems from the early 1920s, it provides a good framework of the sources that are still actively used in international law today. Because of its age, the article does show a few vital flaws. As many of the more modern sources are not included in the article, it is often said to be dated and misleading A. Treaty law 10. A treaty is a formal source of law where States and sometimes other international actors can, through a written agreement, agree that certain obligations will be binding between them.5 Treaties are by far the most important formal source of international law.6 Treaty law finds its codification in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969. B. Customary law 11. All around the world, societies may develop certain standards of behaviour to govern certain relations between them. These standards of behaviour are not codified, but simply develop as social practises which the members of that society all accept. §2. Peremptory norms 12. Peremptory norms or norms of jus cogens are a special class of norms which are regarded as possessing a higher status to 'ordinary rules'.7 Article 53 VCLT defines these norms as "a norm accepted and recognized by the international community of States as a whole as a norm from which no derogation is permitted and which can only be modified by a subsequent norm of general international law having the same character."8 Any ordinary rule, either in treaty law or customary law, is null and void if it is in conflict with a rule of jus cogens.9 5 M. SHAW, International Law (Eighth Edition), Cambride University Press, 2017, 684-685. J. CRAWFORD, Brownlie's Principles of Public International Law (Ninth Edition), OUP, 2019, 28-29; G. HERNANDEZ, International Law (1st Edition), OUP, 2019, 44-45; M. SHAW, International Law (Eighth Edition), Cambride University Press, 2017, 70; D. SHELTON, "Normative Hierarchy in International Law", The American Journal of International Law 100, no.2 2006, 295; H. THIRLWAY, Sources of International Law, Oxford University Press, 2019, 37; J. WOUTERS, Internationaal Recht in Kort Bestek (3e editie), Intersentia, 2020, 15. 7 G. HERNANDEZ, International Law (1st Edition), OUP, 2019, 58-59 and 71; J. WOUTERS, Internationaal Recht in Kort Bestek (3e editie), Intersentia, 2020, 59. 8 Article 53 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties; R. JENNINGS and A. WATTS, Oppenheim's International Law, Ninth Edition, Longman, 1996, 7-8. 9 Article 53 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties; G. HERNANDEZ, International Law (1st Edition), OUP, 2019, 58-59; H. THIRLWAY, Sources of International Law, Oxford University Press, 2019, 163; J. WOUTERS, Internationaal Recht in Kort Bestek (3e editie), Intersentia, 2020, 59. 6 3 13. There is a lot of debate concerning which exact norms constitute norms of jus cogens. Only the prohibition of genocide, prohibition of aggression, injust use of violence, racial discrimination, slavery, piracy, torture and colonialism are widely recognized as peremptory norms.10 §3. Soft law 14. In international relations, States or international organisations often draft instruments, and documents that are not treaties, but still arrange relations.11 This phenomenon is called 'soft law'. 15. These documents or instruments are not binding but still play a very important role in international law. They help contribute to the development of new 'hard law' 12 and generate an expectation of compliance, even if there is no legal binding.13 A good example of soft law is the UN Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, an intergovernmental agreement drafted to present a non-legally binding14, cooperative framework addressing migration in all its dimensions.15 CHAPTER II. IS THERE HIERARCHY BETWEEN THE SOURCES IN ARTICLE 38 (1)? 16. The question of hierarchy between sources of international law most of the times refers to the situation where a rule deriving from a particular recognized source conflicts with a rule deriving from another source of international law. In theory there is a strong presumption against normative conflict in international law.16 In the Right of Passage case the ICJ stated that "it is a rule of interpretation that a tekst emanating from a Government must, in principle, be interpreted as producing and intend to produce effects in accordance with existing law and not in violation of it".17 A lot of the times this is not the case, though. What would happen if two norms of different sources conflict? 17. The question of hierarchy between the sources of article 38 (1) ICJ Statute is not as simple as it might seem at first glance. The article itself does not make mention of a hierarchical order which to some might answer the question of a hierarchy rather quickly. In reality, it is not as simple as it seems. The fourth source of the article, judicial decisions and writings, obviously 10 Barcelona Traction Case, (Belgium v Spain) (Second Phase), 1970, ICJ Rep. 3, para. 33-34; Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States) (Merits), 1986, ICJ Rep. 14, para. 190; Case Concerning Armed Activities on the Terrirtory of the Congo (New Application: 2002), (Democratic Republic of Congo v Rwanda), (Jurisdiction and Admissibility), 2006, ICJ Rep. 6, p64; ILC, "Draft Articles on the Law of Treaties with Commentaries (1966)" in II, Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 187, 248; J. WOUTERS, Internationaal Recht in Kort Bestek (3e editie), Intersentia, 2020, 48. 11 J. WOUTERS, Internationaal Recht in Kort Bestek (3e editie), Intersentia, 2020, 79. 12 H. THIRLWAY, Sources of International Law, Oxford University Press, 2019, 186-187. 13 H. THIRLWAY, Sources of International Law, Oxford University Press, 2019, 189. 14 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, 2018, para. 7. 15 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, 2018, para. 4. 16 "Fragmentation of International Law: Difficulties Arising From the Diversification and Expansion of International Law", Report of the Study Group of the International Law Commission (Finalised by M. KOSKENNIEMI), A/CN.4/L.682, 2006, 25; H. THIRLWAY, Sources of International Law, Oxford University Press, 2019, 152. 17 Case concerning the Right of Passage over Indian Territory (Preliminary Objections) (Portugal v. India) ICJ Reports, 1957, 142. 4 has a subsidiary function, as its description states clearly.18 The third source is often said to merely be a 'non-liquet' or 'gap-filler' and a 'transitory source of international law'. 19 The hierarchical order of the treaties and customary law on the other hand, are heavily debated. 18. In the preparatory works by the Advisory Committee of Jurists, however, we see that Baron Descamps proposed the following: "the following rules to be applied by the judge in the solution of international disputes; they will be considered by him in the undermentioned order".20 Even though this proposition was eventually scratched from the draft during the final discussion in the League of Nations,21 the usual approach of the Court still follows his reasoning for the proposition.22 19. Courts might choose to apply treaty law over customary law and general principles for a few reasons:23 a) The norms in article 38 (1) ICJ Statute are listed in a decreasing order of ease of proof: General principles are more difficult to prove than customary law and customary law is more difficult to prove than a written treaty. b) The enumeration in the article goes from most specific to to most general24: Customary law is often deemed to be quite 'fuzzy and imprecise', leaving the judge a large margin of appreciation. Because of this, treaty law will often be applied as the lex specialis.25 c) The order in the article goes from more consensualist to least consensualist26: Treaties are 'expressly recognized' by States, customary law is only 'accepted as law' and general principles are merely recognized by national systems of law. 18 Article 38 (1) d) ICJ Statute; G. HERNANDEZ, International Law (1st Edition), OUP, 2019, 50; M. SHAW, International Law (Eighth Edition), Cambride University Press, 2017, 92. 19 G. HERNANDEZ, International Law (1st Edition), OUP, 2019, 46-47; A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 934-935 & 941; H. THIRLWAY, Sources of International Law, Oxford University Press, 2019, 160. 20 Procès-Verbaux of the Proceedings of the Advisory Committee of Jurists, 1920, Annexe 3, 306; A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 932; J. WOUTERS, Internationaal Recht in Kort Bestek (3e editie), Intersentia, 2020, 83. 21 A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 932. 22 North Sea Continental Shelf Cases, Judgment, ICJ Reports, 1969, para. 25. 23 A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 932-933. 24 Dispute Regarding Navigational and Related Rights, Judgment, ICJ Reports, 2009, para 35; J. CRAWFORD, Brownlie's Principles of Public International Law (Ninth Edition), OUP, 2019, 20. 25 A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 934. 26 P.-M. DUPUY, "La Pratique de l'Article 38 du Statut de la Cour Internationale de Justice dans le Cadre des Plaidoiries Ecrites et Orales" in Collection of Essays by Legal Advisers of States, Legal Advisers of International 5 20. This means that in theory, there is no formal hierarchy between conventions and custom. Courts are in principle allowed to use their own discretion in choosing which source prevails over the other. In practise courts do, more often than not, apply the sources in successive order, meaning that treaties supersude customary law.27 In rare cases custom might supersede treaty law because of the lex posterior derogat priori rule.28 In the Nicaragua case it was even decided that customary law should not be set aside when its rules are identical to those of treaty law,29 and can even apply customary law without taking the UN Charter into consideration.30 Organizations and Practitioners in the Field of International Law, United Nations, 1999, 381 & 388; H. LAUTERPACHT, International Law. Being the Collected Papers of Hersch Lauterpacht, Volume 1, CUP, 1970, 86-87. 27 R. JENNINGS and A. WATTS, Oppenheim's International Law, Ninth Edition, Longman, 1996, 25-26; A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 932. 28 Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276, Advisory Opinion, ICJ Reports, 1971, para 22. 29 Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States) (Merits), 1986, ICJ Rep. 14, para. 177; A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 935. 30 Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States) (Merits), 1986, ICJ Rep. 14, para. 181; A. PELLET and D. MÜLLER, "Part Three: Statute of the International Court of Justice, Chapter II. Comptence of the Court, Article 38" in A. ZIMMERMAN, C. J. TAMS, K OELLERS-FRAHM and C. TOMUSCHAT, The Statute of the International Court of Justice: A Commentary (3rd Edition), OUP, 2019, 935-936. 6 CONCLUSION 21. International law has many problems where the answer to said problem cannot be found in one simple answer. The hierarchy of sources in article 38 (1) ICJ Statute is one of these problems. As has now been made clear, the hierarchy of sources in article 38 (1) is not as straight forward as one might think. While there is no formal hierarchy in article 38 (1), different hierarchies still get applied in different circumstances. 22. In most circumstances, the courts follow the order in which article 38 (1) ICJ Statute is stipulated. This means that treaties supersede customary law, and customary law supersedes general principles. This is not always the case though. In some cases the courts may decide to have customary law prevail over treaty law, if they believe this would be the best course of action. 7