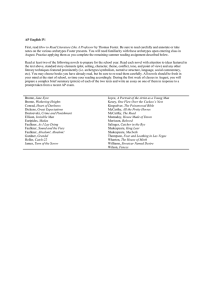

UNIT 01 Speech: Nobel Acceptance Speech by William Faulkner Names of Sub-Units Introduction to History of Novel Prize, William Faulkner’s Biography, Nobel Acceptance Speech by William Faulkner Overview The unit begins by shedding the light upon the history of novel prize. It covers the William Faulkner’s biography, famous authors, Faulkner’s major works and his achievements. Further it covers the famous speech, Nobel Acceptance Speech written by William Faulkner. In the end, unit sheds light into the critique of speech. Learning Objectives In this unit, you will learn to: Understand the Contribution of William Faulkner in Literature Know about the Faulkner’s major works and achievement Grab knowledge about the Nobel Acceptance Speech Learning Outcomes At the end of this unit, you would: Gain insight into the William Faulkner’s Life Analyse the Nobel Acceptance Speech JGI JAIN DEEMED-TO-BE UNIVERSIT Y English Language Pre-Unit Preparatory Material https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nobel-Prize https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1949/faulkner/biographical/ 1.1 INTRODUCTION Throughout its bleak history, the Nobel Prize remains one of our society’s highest honors - so much so that accepting the prize has become an art form in and of itself. Ernest Hemingway’s delightfully laconic meditation on the importance of working alone, Seamus Heaney’s study on the nature and politics of poetry, and Alice Munro’s recent perceptive interview-inlieu-of-speech on writing, gender and the pleasures of storytelling are among history’s finest. But one of the finest comes from William Faulkner, who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1949, twenty years after publishing “The Sound and the Fury”, and gave his acceptance speech on December 10, 1950 at Stockholm City Hall. 1.2 WILLIAM FAULKNER – BIOGRAPHY Absalom, Absalom!, The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying were among William Faulkner’s early works, but he became renowned for his stories set in the American South, often in his fictitious Yoknapatawpha County. Sanctuary, his controversial 1931 novel, was adapted into two films: The Story of Temple Drake in 1933 and a subsequent 1961 attempt. In 1949, Faulkner was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, as well as two Pulitzer Prizes and two National Book Awards. younger years William Faulkner was born in the little Mississippi village of New Albany on September 25, 1897. He got a Christian name which was given by Murry Falkner and Maud Butler Faulkner after his paternal greatgrandfather, William Clark Faulkner. The women in Faulkner’s household had almost as great of an impression on him as the elderly men. Faulkner’s mother and grandmother, Maud Faulkner and Lelia Butler, were passionate readers as well as outstanding artists and photographers, instilling in him the value of form and colour. As a youth, Faulkner was enthralled by drawing. He also enjoyed reading and composing poetry. School bored him, perhaps because of his remarkable brilliance, and he never finished high school. After dropping out, Faulkner began working as a woodworker and, on occasion, as a clerk at his grandfather’s bank. During this period, Faulkner met Estelle Oldham. She was well-known and energetic at the time of their meeting, and she won his heart right away. They dated for a while, though she was already engaged to another man, Cornell Franklin, when Faulkner proposed. Estelle’s parents recommended her to take the offer because Franklin was a law graduate of the University of Mississippi and came from a well-known family. After being crushed by Estelle’s engagement, Faulkner sought out a new tutor Phil Stone, a local lawyer who was enthralled by his poetry. Stone offered Faulkner to live with him in New Haven, Connecticut. There, Stone encouraged Faulkner’s passion for writing. Drawn by the European battle, he joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1918 and trained as a pilot in the inaugural Royal Canadian Air Force. 2 UNIT 01: Speech: Nobel Acceptance Speech by William Faulkner JGI JAIN DEEMED-TO-BE UNIVERSIT Y Early Writings Phil Stone convoyed The Marble Faun, a collection of Faulkner’s poetry, to a publisher in 1924. Faulkner went to New Orleans shortly after the book’s 1,000-copy run. During his time there, he contributed several essays to The Double Dealer, a local publication dedicated to uniting and nurturing the city’s literary community. Soldiers’ Pay was Faulkner’s first novel, and it was released in 1926. He travelled from New Orleans to Europe in 1925 as soon as it was accepted for publication, staying at Le Grand Hôtel des Principautés Unies in Paris for a few months. He wrote about the Luxembourg Gardens, which were a short walk from his home, during his stay. Back in Louisiana, Faulkner received some counsel from American writer Sherwood Anderson, who had become a colleague. Anderson advised the young author to publish about his home state of Mississippi, which Faulkner understood better than northern France. The premise inspired Faulkner, who began writing about the places and people he remembered from his childhood, creating a colorful cast of characters based on real people he knew or heard about, which his great-grandfather, William Clark Falkner also. For his iconic 1929 novel The Sound and the Fury, he invented the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, which is strikingly similar to Lafayette County, where Oxford, Mississippi is located. After one year, in 1930, Faulkner published As I Lay Dying. Famed Author Faulkner’s dictation of Southern speech became renowned for its accuracy and faithfulness. He also aggressively revealed societal concerns like slavery, the “good old boys” club, and Southern nobility that many American writers left out of the loop. Faulkner opted to write Sanctuary, a story about the rape and kidnapping of a young woman at Ole Miss, in 1931 after much debate. Although it startled and outraged some readers, it was a commercial triumph and a watershed moment in his career. Years later, in 1950, he released Requiem for a Nun, a sequel that was a blend of traditional prose and theatrical genres. During this period in his career, Faulkner encountered both elation and heartbreaking despair. Cornell Franklin’s former flame, Estelle Oldham, divorced him between the publication of The Sound and the Fury and Sanctuary. Faulkner, still in love with her, expressed his sentiments right away, and the two married within six months. Estelle gave birth to a daughter in January 1931, whom they called Alabama. Sadly, the premature baby only lived for a little more than a week. “Estelle and Alabama” is the subject of Faulkner’s collection of short stories. Light in August (1932), Faulkner’s next work, depicts the story of Yoknapatawpha County misfits. In it, he unveils Joe Christmas, a man of ambiguous racial makeup; Joanna Burden, a woman who supports black voting rights and is eventually gunned down. Lena Grove, a vigilant and determined young woman, searching for her baby’s father; and Rev. Gail Hightower, a man plagued by visions. It was named one of the 100 finest English-language novels from 1923 to 2005 by Time magazine, with The Sound and the Fury. Screenwriting Faulkner went to screenwriting after writing numerous outstanding works. With a six-week contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer under his belt, he penned Today We Live, a movie featuring Joan Crawford and Gary Cooper, in 1933. Faulkner chose to sell the rights to the picture Sanctuary, eventually dubbed The Story of Temple Drake, after his father died and he needed money (1933). Estelle gave birth to Jill, the couple’s sole surviving child, in the same year. Between 1932 and 1945, Faulkner worked as a scriptwriter in Hollywood a dozen times, contributing to or writing many pictures. He did it mainly for financial benefit, though, as he was unimpressed by the work. 3 JGI JAIN DEEMED-TO-BE UNIVERSIT Y English Language In the course of this period, Faulkner also various novels which included the epic family tale Absalom, Absalom! (1936), the satire The Hamlet (1940), and Go Down, Moses (1942). Nobel Prize Win The Portable Faulkner, released by Malcolm Cowley in 1946, reignited interest in Faulkner’s writings. Faulkner wrote Intruder in the Dust two years later, a story about a black man wrongfully accused of murder. For $50,000, he was able to sell the movie rights to MGM. The most memorable moments of Faulkner’s life was receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1949. He was named one of the most prominent writers of American letters by the committee. With all of the attention, he received more honours, such as the National Book Award for Fiction and the Legion of Honor in New Orleans for Collected Stories. For The Collected Stories of William Faulkner, he earned the National Book Award in 1951. In 1955, Faulkner won the Nobel Prize in Literature and another National Book Award for his novel A Fable, which is set in France during WWI. Death In January 1961, Faulkner bequeathed all of his main manuscripts as well as a large number of personal documents to the University of Virginia’s William Faulkner Foundation. Faulkner died of a heart attack on July 6, 1962, which happened to be the Old Colonel’s birthday. In 1963, he received his second Pulitzer Prize for The Reivers, which was given to him unexpectedly. Faulkner left an indelible literary legacy and is still regarded as a respected writer of the rustic American South, adeptly capturing both the region’s beauty and its grim past. 1.2.1 William Faulkner’s Major Works Light in August One of Faulkner’s most blatant observations on racial strife in the South is Light in August. The theme of colour and racial distortion in the hot August sun plays a major role in the three interconnected episodes. Reverend Gail Hightower, Lena Grove, and Joe Christmas cross paths, each looking for a place to call home. The way characters see themselves frequently differs from how others see them. Although there are strong emotions present and not all of the narratives end pleasantly, this quest for self is a philosophical voyage. As I Lay Dying This is Faulkner’s sixth novel, and it is often regarded as his best. It was dubbed “a tour-de-force” by him. With fifteen narrators and fifty-nine chapters, As I Lay Dying takes us through the funeral of Addie Bundren, the Bundren family matriarch. “My mother is a fish,” is the title of one chapter, and the rest of the book is just as personal. After Addie’s death, glimpses into the fragility of children, friends, and partners are seldom less than tragic. This novel, like others by Faulkner, includes a physical trip in addition to the philosophical one. “For range of effect, intellectual weight, uniqueness of style, diversity of characterisation, comedy, and tragic depth of Faulkner’s writings are without rival in our time and country,” said Robert Penn Warren. Absalom, Absalom! Faulkner’s novel Absalom, Absalom! is one of the few in which he addresses the idea of location outside of the South. It is recounted by Quentin Compson and his Harvard companion, Shreve and concentrates 4 UNIT 01: Speech: Nobel Acceptance Speech by William Faulkner JGI JAIN DEEMED-TO-BE UNIVERSIT Y on the story of Thomas Sutpen, who arrives in Mississippi in the 1830s to establish a plantation and an empire. The reader is left with a frightening uncertainty due to the distance between the narrators and their experiences. Who had the upper hand? Who can we put our faith in? Although no one who narrated the narrative got the facts right, according to Faulkner, the reader can seek out the truth. It’s a long book (1,300 words each sentence), but it’s a great opponent. The Sound and the Fury The setting is Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, which is the backdrop for several of Faulkner’s writings, and the focus is on the Compson family (as shown above in Absalom, Absalom!). It’s broken down into four sections (five if you count the appendix, which isn’t included in certain updates), each focusing on a different family member. The Compson family’s and their social order’s slow, agonising demise tugs at the heartstrings. Adultery, mental issues, and honour are all themes that run through their lives, wreaking chaos and mayhem. “They endured,” is the last sentence of the appendix. A Fable While Faulkner regarded A Fable to be his finest achievement, he worked on it for over a decade, and critics gave it mixed response, thus it is recognised as a lesser novel. Despite winning the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award in 1955, it remains unpublished. It is, nevertheless, worth reading because of the abrupt departures from his usual fare: set in France during World War I, it follows a sergeant and his comrades as they confront the concepts that underpin war. The metaphor of the Christ narrative is evident, but it is no less heart-breaking because Faulkner subtly makes it his own. It may be difficult to read at times, but the stories all come together in a thrilling conclusion. The Reivers The Reivers is part of Faulkner’s favorite family, the McCaslins, and is little known but highly regarded by those who have read it. The Reviers is a story within a story, told to a youngster by his grandfather, about Lucius and Boon Hogganbeck’s voyage to Memphis in Lucius’s grandfather’s shiny new car. While the rest of the family is away, Boon, the family’s tag-along servant, invites Lucius (not yet eleven) on a thrilling adventure, and the two battle, strive, and bet their way across the South. The Reivers is undoubtedly Faulkner’s funniest work, full of wild hilarity that is only enhanced by the unexpected twists that characterise all of his writing. 1.2.2 William Faulkner’s Achievements, Collections and Critical Reception Achievements For his ‘significant contribution to the modern American novel’, he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949. In 1951, he was awarded the title of “Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur.” In 1955 and 1963, he earned two Pulitzer Prizes for his books, “A Fable” and “The Reivers,” the latter of which was awarded unexpectedly. Collections At the time of his death, the University of Virginia was designated as the keeper for William Faulkner’s important manuscripts and documents. His stated goal was realised when the William Faulkner Foundation was established, to which he bequeathed his papers. 5 JGI JAIN DEEMED-TO-BE UNIVERSIT Y English Language They were eventually moved to the University of Virginia Library with the help of Faulkner’s friend Linton R. Massey, the benefactor of the University of Virginia Library’s huge collection of Faulkner first editions, adaptations, and all writings pertaining to the writer’s life and work. Audio recordings of Faulkner’s speeches during his term as writer-in-residence at the University of Virginia are also included in the collection. Jill Faulkner Summers, Faulkner’s daughter, donated two pieces of his personal library to Special Collections in July 1998 and October 2000. Critical Reception William Faulkner’s work has had a long and complicated critical acclaim. Faulkner is one of the most widely discussed authors in the English language, with works ranging from biographies to the most scholarly criticism. Every year, a large number of books and articles are produced, making it impossible for even the most dedicated Faulkner fans to keep up. Given the intimidating nature of this body of work for someone new to the field, the goal here will be to acclimate the reader, not only in terms of what has been printed, but also in terms of the broad trends that have emerged over the six decades since a recognisable society of Faulkner scholars arose and the eight decades since people have been making comments on his work. This initial essay is organised to fit both the historical and thematic evolution of this critical response as much as possible. It has a recursive quality to it, like any other discipline of academia, in that it returns to topics. Scholarly debates frequently return to specific places, even when new interests emerge, just as families relate the same stories or sports fans debate critical referee decisions years later. 1.3 SPEECH: NOBEL ACCEPTANCE SPEECH By WILLIAM FAULKNER Ladies and Gentlemen, I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work – a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before. So, this award is only mine in trust. It will not be difficult to find a dedication for the money part of it to commensurate with the purpose and significance of its origin. But I would like to do the same with the acclaim too, by using this moment as a pinnacle from which I might be listened to by the young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will someday stand here where I am standing. Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat. He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed – love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labours under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands. Until he relearns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last dingdong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock 6 UNIT 01: Speech: Nobel Acceptance Speech by William Faulkner JGI JAIN DEEMED-TO-BE UNIVERSIT Y hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail. From Nobel Lectures, Literature 1901-1967, Editor Horst Frenz, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1969 Source: MLA style: William Faulkner – Banquet speech. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2021. Fri. 24 Sep 2021. <https://www. nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1949/faulkner/speech/> 1.3.1 Speech Summary and Analysis In December 1950, the Willaim Faulkner was honored with the Novel Prize in Literature and his acceptance speech got a title of “ The Writer’s Duty”. Faulkner’s post-World War II address aims to persuade young authors of the significance of literature. To achieve his goal of encouraging young authors, he methodically arranges the speech, chooses specific style aspects to employ, and appeals to his readers in a variety of ways. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “The Writer’s Duty,” William Faulkner methodically structures his speech to best show his goal. He opens his speech by presenting his topic, writing, and explaining how the process requires a lot of effort, “but to my work - a life’s labour in the agony and misery of the human spirit,” later referring to writing as “anguish and travail.” Then, by discussing the flaws in present literature, he begins to demonstrate his target audience: The youngsters writing today have forgotten the issues of the human heart in battle with itself, which alone may generate good writing because only that is worth writing about. He then goes on to explain why his goal is legitimate. Because of the way he arranges his sentences, Faulkner is able to convey his message to the audience without having them feel as if he is shoving it down their throats. To convey his message, Faulkner employs a variety of metaphorical language and stylistic aspects. He uses crucial terms like agony, pity, compassion, honour, endurance, and courage repeatedly in his speech. He accentuates these words by repeating them, which draws the reader’s attention to them. The words he chooses to emphasise are also terms that elicit strong emotional responses. People take words like perseverance and courage seriously because they generate feelings and experiences. Faulkner is well aware of this and makes use of it. These words also serve to convey his speech’s tone. Words like sacrifice and love indicate that Faulkner is using a serious tone in his writing. All of Faulkner’s stylistic features in his essay work together to show his point of view. In order to appeal to his audience and achieve his goal, Faulkner intentionally arranges and employs aesthetic components in his essay. “Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it,” he says, rationally appealing to his audience by referring to something they all comprehend. There are no longer any spiritual issues. Only one question remains: “When will I be blown up?” His audience could all connect to this because they had all gone through WWII, and he knew what they were thinking. Throughout the speech, he makes numerous references to his audience’s morality, such as “It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage, honour, hope, pride, compassion, pity, and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past.” 7 JGI JAIN DEEMED-TO-BE UNIVERSIT Y English Language Faulkner places a high value on writing while also convincing his readers that doing the right thing for humanity is a moral imperative. Faulkner makes multiple emotional pleas to the audience; he utilises such strong emotional diction throughout the speech that it draws the listener’s attention and tugs at their heartstrings. Although Faulkner employs a variety of appeals to reach his target audience and achieve his goal, it is the combination of all of them that makes his appeal so effective. William Faulkner was mainly successful in communicating his objective and reaching his audience in “The Writer’s Duty,” but no text is faultless. Faulkner excelled in appealing to the emotions and morals of his audience. He frequently utilised emotionally charged language and made assertions that were directed at the audience’s morals. Faulkner, on the other hand, did not rely heavily on the reader’s logic. This is a minor flaw in an otherwise excellent speech. This speech would have been much stronger if Faulkner had rationally explained in greater depth how literature ties to humanity’s resilience. Faulkner achieves his goal in “The Writer’s Duty” by combining the structure of his speech, stylistic aspects, and appeals to his intended audience. William Faulkner’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “The Writer’s Duty,” is a powerful and insightful speech that has affected many authors and continues to inspire others. 1.3.2 Critique of William Faulkner’s Nobel Prize Speech William Faulkner, a writer from Oxford, Mississippi, won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1949. Since the outbreak of World War II, he was the first American novelist to earn this distinguished honor. It’s crucial to understand the context of his acceptance speech. World War II was recently concluded by the use of nuclear weapons, the cold fight with the Soviet Union is still ongoing, and there are rumors of a war with Korea. The threat of a nuclear holocaust is a global issue. He explains why he is optimistic about the human race’s future. Faulkner challenges young authors to write about “the human heart in conflict” in his address. He claims that it is their responsibility to show us that there is reason to be optimistic. A less evident objective of this speech is to emphasise that we all have a say in how our future turns out. The appeal is mostly emotional. Given the state of the world at the time, Faulkner does combine emotion with logical argument. He admits the general fear of nuclear disaster as he wonders, “When will I be blown up?” He then warns the young poets and authors that they must not let their worries stifle their efforts to write about man’s virtues. When Faulkner says that it is a “duty” and “privilege” to “help man endure” whatever problems we may encounter, he is appealing to the sentiments of aspiring authors as well as the rest of us. His claim that “heart in conflict” concerns are the only topics worth writing about is exaggerated, but it does support his thesis. We need to think about and reflect on the values that offer us reason to be hopeful. We do, he says, have the potential for “compassion, sacrifice, and endurance.” Mr. Faulkner used loaded language to elicit the audience’s support. Conclusion 1.4 CONCLUSION The central theme of Faulkner’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech is that writers must rise beyond the terror that characterised the Cold War era; they must focus on the only thing worth writing about, which is “the human heart in struggle with itself.” William Faulkner was a misunderstood author who 8 UNIT 01: Speech: Nobel Acceptance Speech by William Faulkner JGI JAIN DEEMED-TO-BE UNIVERSIT Y went on to become one of the most well-known. He utilises his Nobel Prize acceptance speech to convey his views on how great and significant works of literature should be written to his audience. His efficacy was aided significantly by rhetorical tactics. Persuasive appeals, figurative language, syntax, tone, and diction are all rhetorical tactics that add to the speech’s efficacy. 1.5 GLOSSARY Prose: A verbal or written language that follows the natural flow of speech. Mayhem: It refers to needless or willful damage or violence. 1.6 SELF-ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS A. Essay Type Questions 1. Write about the life of William Faulkner in short. 2. Write a note about William Faulkner’s Achievements and Collections. 3. Explain in short, the message that William Faulkner tries to convey through his acceptance speech. 1.7 ANSWERS AND HINTS FOR SELF-ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS A. Hints for Essay Type Questions 1. William Faulkner was born in the little Mississippi village of New Albany on September 25, 1897. He got a Christian name which was given by Murry Falkner and Maud Butler Faulkner after his paternal great-grandfather, William Clark Faulkner. The women in Faulkner’s household had almost as great of an impression on him as the elderly men. Refer to Section William Faulkner – Biography 2. For his ‘significant contribution to the modern American novel’, he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949. In 1951, he was awarded the title of “Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur.” Refer to Section William Faulkner – Biography 3. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “The Writer’s Duty,” William Faulkner methodically structures his speech to best show his goal. He opens his speech by presenting his topic, writing, and explaining how the process requires a lot of effort, “but to my work - a life’s labour in the agony and misery of the human spirit,” later referring to writing as “anguish and travail.” Refer to Section Speech: Nobel acceptance speech by William Faulkner @ 1.8 POST-UNIT READING MATERIAL https://studylib.net/doc/8996910/rhetorical-analysis-of-william-faulkner-s-acceptance-spee... 1.9 TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION FORUMS Discuss the role and duty of young minds to contribute to the field of Literature. 9