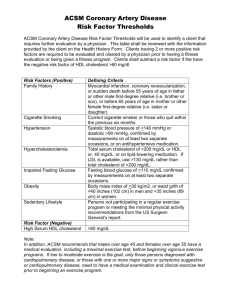

Resistance based Group Intervention Introduction In the UK obesity is on its rise and there is an increased concern to whether there are any efficient strategies to halt the problem. The U.S is estimated to be a decade ahead in terms of the evergrowing rise in obesity levels which is in-turn drastically increasing the rate of type 2 diabetes. Results show obesity contributes to £3.5bn in economy costs, 30,000 deaths and 18 million days off sick from work each year. It can also lead to major health problems such as diabetes, hypertension and several more. Obesity is an overabundance of body fat and can be defined in relation to body mass index (BMI), a BMI value >30 indicates an individual is obese and is reflected by an increased waist circumference (Haslam, Sattar, & Lean, 2006). Therefore, effective exercise prescription is essential to help with weight gain prevention and weight loss maintenance, although it is evident that encouraging obese individuals to partake in physical activity isn’t an easy task. Often people who are overweight or obese suffer from low self-esteem, possible eating disorders, depression, and anxiety (Ehrman, Gordon, Visich, & Keteyian, 2018). Low adherence to exercise is a common problem and can be due to high levels of displeasure, research states individuals perform better with self-selected intensities which elicit a more pleasurable response (Ekkekakis, 2009). Multi-component behavioural weight management programs (BWMP) have been developed and widely used most abundantly in primary care settings, they address physical activity, nutrition, and behaviour therapy, although, these programs have seen to have varied outcomes. Loveman, et al., (2011) conducted a systematic review on the effectiveness of long=term weight management schemes for adults and found the interventions had generally produced modest weight loss in overweight or obese subjects, however weight regain was common, additionally these interventions were likely to be cost-effective. An update review with a more calloborative approach used by NICE, (2013) reported the effectiveness of 44 different BWMP’s compared to control coniditons, participants in the control condition had produced acute weight loss over a 12+ month period, whereas the intervention groups produced signifcantly greater results in most cases, 2-3kg more weight reducution in a 12-18 month period. There had also been evidence that suggests interventions involving face-to-face contact, set goals and supervised exercise yielded the most benefit compared to other interventions, this indicates the the potential necessity for assistance and contact to elciit greater results. Overall, BWMP’s may play a crucial role in the assistance of adopting a healthier and active lifestyle. Referral Criteria (ethnic groups include, week 2 lecture tier systems) Participants will be eligible for the program if they match the referral criteria, this criterion is evidence based using the guidelines associated with ACSM, (2013). Their body mass index (BMI) should indicate that they’re overweight or obese, 25 – 29.9 kg/m2 (overweight), ≥30kg/m2 (obese). In addition to BMI, waist girth measurements will also be taken, an obese individual will be measured at a waist girth >102cm(40inch) for men and >88cm(35inch) for women (Executive summary of the clinical guidelines, 1998). Old age, physical inactivity and race are some of the factors that can contribute to hypertension, participants may be referred if they have levels above normal, SBP – 120-139/ DBP – 80-89 (Prehypertension), Stage 1 & 2 hypertension are excluded from criteria. An unhealthy diet with an abundant quantity of processed foods containing high saturated fat or trans fats can increase cholesterol levels – leading to dyslipidaemia. Participants may be referred if their LDL cholesterol is 130-159 mg∙dL-1, total cholesterol is 200-239 mg∙dL-1 , HDL cholesterol ≥60 mg∙dL-1 and triglycerides are 150-199 mg∙dL-1 . Individuals at risk of Type 2 Diabetes with fasting plasma glucose levels exceeding optimal levels are also considered, this is largely subject to an individual’s weight and waist circumference which can lead to insulin resistance. Prediabetic plasma glucose ranges from 100 mg∙dL-1 to 125 mg∙dL-1 for impaired fasting glucose and 140 mg∙dL-1 to 199 mg∙dL-1 for impaired glucose tolerance. Individuals with higher values than prediabetic values will more than likely be diabetic and therefore excluded from the criteria. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) potential is exacerbated due to all above criteria; therefore, all are leading causes of CVD. Additionally, cigarette smoking (or recent cessation/ in the last 6 months) and sedentary lifestyle behaviours (failure to partake in at least 30 min of moderate intensity exercise 3 times per week) are considered lifestyle factors that may lead to increased risk of CVD – and are also considered as referral criteria for this program. Workshop entry process and progress monitoring Pre-Participation Health Screening Participants are required to complete a range of pre-participation processes that indicate the physical readiness of the individual and to consider any metabolic complications one may have before engaging in physical activity. Following a similar approach to ACSM, (2013), there will be a multistage process, including AHA/ACSM Health/Fitness Facility Preparticipation Screening Questionnaire ACSM, (2009), an informed consent, a CVD risk factor assessment and classification, and medical evaluation (if required) that involves a physical examination and stress test by a reputable health care professional. All individuals will be required to complete at minimum, the health screening questionnaire and informed consent form. The AHA/ACSM Health/Fitness Facility Preparticipation Screening Questionnaire (see figure 1), allows individuals with multiple CVD risk factors to be properly assessed by a professional prior to engaging in physical activity, this is mandatory as part of regular effective medical practice and should progress incrementally alongside their prescribed exercise program (ACSM, 2009). A CVD risk factor assessment allows the health care professional to acquire relevant information regarding the patient’s development and on-going progression/regression. Determining the presence of metabolic and cardiovascular disease is essential for when making decisions regarding the level of medical clearance, the need for exercise testing and the level of exercise supervision and exercise frequency (ACSM, 2013). The informed consent is required before exercise in any health/fitness or clinical setting, this documentation is an important part of ethical and legal consideration. The form allows the participant to understand what is required of them and the purpose and risks associated with the exercise test/program (ACSM, 2013). Figure 1 AHA/ACSM Health/Fitness Facility Preparticipation Screening Questionnaire Note: Adopted from American College of Sports Medicine. (2013). ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p25, fig 2.2. Figure 2 and 3 adopted from ACSM, (2013) are representative of the CVD assessments that the health practioner will require from each patient. This is necessary to identify the level of risk which will therefore determine the exercise regime. For example, if the patient has numerous CVD risk factors (≥2) they will likely be classified as moderate or high risk, or a combination of both, in this case, with the given referral criteria, the individuals will more than likely be classified as moderate risk. This can then be progressed to identify which level of intensity is or isn’t advised when working with patients, In Figure 3, this model allows the practioner to address whether a medical examination, exercise test and physician supervision are necessary for pre-participation health screening, however, if not required, the patient may still be eligible to request the examination if they believe they’re at risk. Figure 2 Logic model for classification of risk Note: Adopted from American College of Sports Medicine. (2013). ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p26, fig 2.3. Figure 3 Medical examination based on risk classification Note: Adopted from American College of Sports Medicine. (2013). ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p28, fig 2.4. If the patient has answered the CV assessment (see figure 2) and shows signs of metabolic complications, they will be required to consult a physician prior to starting an exercise program, there is evidence that if an individual of whom is unaccustomed to physical activity and performs bouts of vigorous intensity exercise, the likelihood of an exercise-related event such as sudden cardiac death or acute MI is increased (Giri, et al., 1999; Siscovick, et al., 1984). Therefore, the most appropriate approach would be to start with light-to-moderate intensity levels of exercise and progress incrementally as their physical fitness increases. Pre-participation – Assessments (Physiological, Psychological & Nutrition) Once the patient has completed their initial step within the pre-participation process, they will then be taken through various assessments that will be repeated throughout the 12-week intervention, patients will be required to take part in the tests at the start, after six weeks and the twelfth week – totalling three compulsory testing events. The patients will be asked to participate in a 6-month follow up post-intervention to highlight the long-term effects and thus asked to repeat all the range of assessments below to evaluate the long-term health effects of this program. Blood Pressure (BP) Patients will have their blood pressure measurement taken before exercise participation. This is an important factor to consider when addressing an individual’s health and well-being. Prehypertensive individuals included in the referral criteria require health-promoting lifestyle alterations to prevent the progressive rise in blood pressure, as this indefinitely increases the likelihood of developing CVD (Chobanian, et al., 2003). As this intervention involves overweight and obese patients, they will most likely need modifications when undergoing a blood pressure test, one main modification is that the individual will likely require a larger cuff size. Measurement of blood pressure will follow the same methodology from Prineas, (1991). It is expected that, by the halfway point of the program, patients will see a decrease in their BP, with further reductions by the end point of 12 weeks, with the future expectation to return to normal levels (<120 mm Hg SBP, <80 mm Hg DBP) (ACSM, 2013). Numerous substantial epidemiological studies have shown that a reduction in weight leads to a BP lowering effect, likely due to improving insulin sensitivity (Mertens and Van Gaal, 2000). Cholesterol Levels Next, the patients will be required to have their blood taken to examine cholesterol levels NHS (2019), with the aim to reduce low-density lipoproteins (LDL), as this is a major risk factor for CVD, thus lowering LDL results in a significant reduction in the incidence of CVD (12), further, to increase the levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDL) to combat the chances of developing CVD (ACSM, 2013). Smoking, overweight/obese status, sedentary lifestyle, and poor nutrition habits all contribute to the raise in cholesterol levels (NHS, 2019). The program hopes to reduce cholesterol levels, seeing a decline by week 6 and further reductions by week 12 – with the expectation to reach normal levels by the end of the intervention. Normal levels = LDL – 100-129 mg∙dL-1, Total cholesterol <200 mg∙dL1 , HDL – 40-60 mg∙dL-1, Triglycerides <150 mg∙dL-1 (NCEP, 2004). Plasma Glucose Levels Testing for glucose levels can be done via blood samples NHS (2020), like testing for cholesterol levels, therefore both can be checked simultaneously. Prediabetic patients within this program will have both impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and are at a significantly high risk for developing diabetes (10). Reduction in weight can make it easier to achieve a lower blood sugar level, leading to improved insulin response and sensitivity, this program aims to reduce body weight and improve blood sugar levels week by week with appropriate diet and exercise. By the end of the 12 weeks, the patient will have lowered both (IGT & IFG) levels appropriately, aiming for close to 100 mg∙dL-1. Anthropometric Measures Patients would have already identified their BMI and waist circumference (WC) prior to joining the program, their BMI and (WC) will be recorded at the point of starting the program, in the middle and at the end (1,6,12 weeks). Along with BMI, circumference measures will be taken by the practioners using a measuring tape, measures of the waist, upper arm, hips, calf, mid-thigh, neck, and calf will all be required for recording at the same intervals throughout the program (1,6,12 weeks). Using the same methodology seen in the manual of Callaway and colleagues, (1988). It is essential that all patients achieve reduction in girth measurements, with the addition of a lower BMI score throughout the program, with the emphasis of reducing WC to prevent the probability of CVD, hypertension, diabetes, and early death (Pi-Sunyer, 2004). According to the guidelines addressed by ACSM (2013), normative values of WC for men and female are as follows: 28.5–35inch / 31.5– 39.0inch, therefore these values will be the target for individuals of this program, achieving a reduction in both BMI and WC respectfully. Resting Heart Rate (RHR) In addition to the measures above, practioners will need to take a resting heart rate from all participants, this is not included in the referral criteria, so a varied range of RHR are expected. However, it is known that a RHR ≥90 beats per min(bpm) compared to <60bpm yields at least a twofold increase in CVD mortality, the method associated with taken RHR is adopted from Cooney, et al., (2010). 6 Minute Walk Test (6MWT) To test exercise capacity, this program will involve a 6-minute walk test, the distance the individual covers is the prime outcome measure of the test, secondary measurements will include fatigue and dyspnoea that will be rated via a borg scale Williams (2017), and will be administered at the start, middle and end of the intervention. The method for this specific test is adopted from Enright (2003) and inherits a non-intrusive approach to gaining knowledge as to where the patient is in terms of their fitness level. Furthermore, this test requires no equipment and can be performed anywhere if the patient has a means of recording distance travelled via electronic device plus a stopwatch. The table below contains an equation that is an acceptable method to predict VO2 peak from the 6MWT: Table 1: VO2 peak equation Note: Adopted from Cahalin, et al., (1996) Strength Testing To test muscular strength, a gym facility will be used, all participants will partake in a six-repetition max test (6RM) using both a leg press and chest press machine. They will be supervised by a practioner to ensure adequate technique and methodology behind the test will be adopted from Logan and colleagues (2000). A 6RM can be deemed more appropriate than singular maximal rep due to the population used for this study; as they’re at risk to developing CVD and other health conditions. This test will commence at the start, middle and end of the exercise program, practioners will record the weights lifted for each patient and the goal will be to increase the weight used for each future test. Psychological Testing/Questionnaire Each patient will fill and complete a quality-of-life questionnaire (QOLQ) created by Moorehead and colleagues (2003). It will be assigned to patients at the start and end of the intervention, this questionnaire covers multiple areas of an individual’s life and can be used to assess whether some if not all elements have improved. Further, the QOLQ can be completed in less than one minute, and can be administer to patients via email, Nutritional Analysis Participants will be asked to provide a 3-day food diary at the start of the intervention for the health practioner to assess, it is very likely that there should be amendments to the participants eating habits to allow for progressive weight loss. The diary should provide all food and beverages with as close to exact measures of each. 12-Week Program Content and Delivery Week 1: Day 1 •Screening & Testing Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 You should clearly outline content of the 12-week mutli-component BWMP and how it will be delivered. Make reference to equipment / facilities that are required. Also ensure that you choose an underpinning psychological model for your programme to follow. (Transtheoretical Model) Programme content must include elements of diet, physical activity and behavioural therapy. You should be making individuals aware of the consequences and prevalence of obesity, acknowledging and quantifying lifestyle and risk factors associated with overweight / obesity. Promote healthy lifestyle options. This can be delivered in a commercial or non-commercial setting such as those delivered in primary care setting. Delivery of the programme needs to be made clear and may include group workshops or individual consultations on a range of topics that would be beneficial for the patients. You may also provide them with supplementary materials that you feel is important. There may also be online aspects of the programme. Where possible use peer-reviewed scientific research to compliment your choice of methods and content. References Ehrman, J. K., Gordon, M. P., Visich, P. S., & Keteyian, S. J. (2018). Clinical Exercise Physiology. Human Kinetics, 282. Ekkekakis, P. (2009). Let them roam free? Physiological and psychological evidence for the potential of self-selected exercise intensity in public health. Sports medicine, 857–888. Haslam, D., Sattar, N., & Lean, M. (2006). ABC of obesity. Obesity--time to wake up. Clinical research ed, 640-642. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. (1998). Obesity research, 6 Suppl 2, 51S– 209S. Stamler J. (1991). Blood pressure and high blood pressure. Aspects of risk. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979), 18(3 Suppl), I95–I107. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.18.3_suppl.i95 DeFronzo, R. A., Ferrannini, E., Groop, L., Henry, R. R., Herman, W. H., Holst, J. J., ... & Weiss, R. (2015). Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nature reviews Disease primers, 1(1), 1-22. Stanner, Sara & Coe, Sarah & Frayn, Keith. (2019). Cardiovascular Disease: Diet, Nutrition and Emerging Risk Factors, John Wiley & Sons Ltd Second Edition. 293-309. 10.1002/9781118829875.ch12. Glyn-Jones, S., Palmer, A. J. R., Agricola, R., Price, A. J., Vincent, T. L., Weinans, H., & Carr, A. J. (2015). Osteoarthritis. The Lancet, 386(9991), 376-387. American College of Sports Medicine. (2013). ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. (1998). Archives of internal medicine, 158(17), 1855–1867. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.17.1855 American College of Sports Medicine, Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(7):1510–30. Siscovick DS, Weiss NS, Fletcher RH, Lasky T. The incidence of primary cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise. N Engl J Med. 1984;311(14):874–7. Giri S, Thompson PD, Kiernan FJ, et al. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of exertion-related acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1731–6. Chobanian, A. V., Bakris, G. L., Black, H. R., Cushman, W. C., Green, L. A., Izzo, J. L., Jr, Jones, D. W., Materson, B. J., Oparil, S., Wright, J. T., Jr, Roccella, E. J., National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, & National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee (2003). The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA, 289(19), 2560–2572. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.19.2560 Prineas R. J. (1991). Measurement of blood pressure in the obese. Annals of epidemiology, 1(4), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/1047-2797(91)90043-c Mertens, I. L., & Van Gaal, L. F. (2000). Overweight, obesity, and blood pressure: the effects of modest weight reduction. Obesity research, 8(3), 270-278. NHS England, (2019). Cholesterol levels. High cholesterol - NHS (www.nhs.uk) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cholesterol Education Program; 2004 [cited Mar 19]. 284 p. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/index.htm NHS England, (2020). Type 2 Diabetes. Type 2 diabetes - NHS (www.nhs.uk) Callaway CW, Chumlea WC, Bouchard C, Himes JH, Lohman TG, Martin AD. Circumferences. In: Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R, editors. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 1988. p. 39–80 Pi-Sunyer F. X. (2004). The epidemiology of central fat distribution in relation to disease. Nutrition reviews, 62(7 Pt 2), S120–S126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00081.x Cooney, M. T., Vartiainen, E., Laatikainen, T., Juolevi, A., Dudina, A., & Graham, I. M. (2010). Elevated resting heart rate is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease in healthy men and women. American heart journal, 159(4), 612–619.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.029 Enright P. L. (2003). The six-minute walk test. Respiratory care, 48(8), 783–785. The Six-Minute Walk Test (rcjournal.com) Williams, N. The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale, Occupational Medicine, Volume 67, Issue 5, July 2017, Pages 404–405, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqx063 Cahalin, L. P., Mathier, M. A., Semigran, M. J., Dec, G. W., & DiSalvo, T. G. (1996). The six-minute walk test predicts peak oxygen uptake and survival in patients with advanced heart failure. Chest, 110(2), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.110.2.325 Reynolds, J. M., Gordon, T. J., & Robergs, R. A. (2006). Prediction of one repetition maximum strength from multiple repetition maximum testing and anthropometry. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 20(3), 584–592. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-15304.1 Logan P, Fornasiero D, Abernathy P. Protocols for the assessment of isoinertial strength. In: Gore CJ, editor. Physiological Tests for Elite Athletes. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2000. p. 200–21. Moorehead, M. K., Ardelt-Gattinger, E., Lechner, H., & Oria, H. E. (2003). The validation of the Moorehead-Ardelt quality of life questionnaire II. Obesity surgery, 13(5), 684-692.