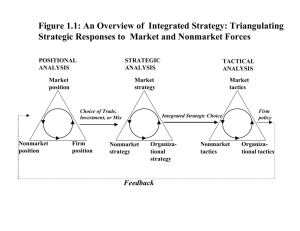

The News Media and Nonmarket Issues - Baron highlighetd

advertisement