CreativityAnOverviewofthe7CsofCreativeThoughtLubartThornhill-Miller2019inPsychofHumanThoughtSternbergFunke2019Chptwcoverbib2fullsize

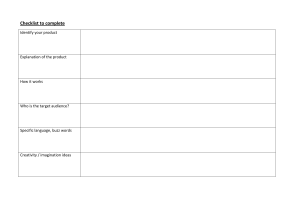

advertisement