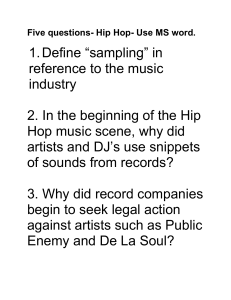

Woman's Art, Inc. !"#$%&'()*+)+&*%&,-$.$%/&'&0-"12("%)&,)(3445$ '3)6"(7+8/&9%4(*.&9%4$5#:% ;$<*$-$.&-"(=7+8/ ,"3(>$/&!"#:%?+&'()&@"3(%:5A&B"5C&DA&E"C&F&7,G(*%4&1&,3##$(A&FHIJ8A&GGC&F1K L3M5*+6$.&MN/&Woman's Art, Inc. ,):M5$&O;P/&http://www.jstor.org/stable/1357877 . '>>$++$./&QRSFTSTQFF&QD/DI Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Woman's Art, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Woman's Art Journal. http://www.jstor.org Issues and Insights Artists Women in Sweden: A Two-Front Struggle INGRID INGELMAN The year 1864 was an important one for women artists in Sweden: it was the year that the 130-year old Swedish Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, the only institution in Sweden offering an education in the fine arts, opened a class for women in its schools of painting and sculpture. 蓬勃發展的 There was a flourishing of art activity in Sweden surrounding the Academy's founding in 1735, with sculptor Johan Tobias Sergel and painters Carl Gustaf Pilo, Gustaf Lundberg, Alexander Roslin, and the family Pasch receiving national, even international renown. All, however, also studied abroad-Sergel in Rome, Pilo in Copenhagen, where he remained, and Roslin and Lundberg in Paris, where they achieved great success. Contact with mainstream European art was close, and most of the artists' works reflected current European art styles. Recognized artists were appointed members of the Swedish Academy, thus insuring their ⼯匠 social position, but many more lived and worked as artisans. By the end of the 18th century, Swedish art activity went into decline, not to revive again until the latter part of the next century. After completing their studies at the Academy, art students began going to Dusseldorf in the 流派 1860s, where they became genre painters, and later to Paris, where most identified with the plein-air landscape painters. The generation schooled in France opposed the Academy's antiquated teaching methods and in 1886 formed the Artist's Union. This was the first of the artist groups that 擴散 增⽣ began proliferating in Sweden, as elsewhere, at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. The Artist's Union introduced Romanticism to Sweden in the 1890s. 蝕刻 Associated with the group were etcher, watercolorist, and 2 Anders the late-born romantic painter Zorn; portraitist Ernst Josephson;Carl Larsson, popular painter and illustrator; Bruno Liljefors, a painter of wild animals in their natural surroundings; portraitist Richard Bergh, who reorganized the Swedish National Museum; and landscapists Nils Kreuger and Karl Nordstr6m, as well as Prince Eugen. Although women were associated with the Artist's Union, none achieved the status of their male colleagues. Even in histories of the association, the women are reduced to mere footnotes, as they are elsewhere in Swedish art history. 3Were they all poor artists or were there other reasons for this neglect? In an attempt to answer these questions, I gathered all the accessible data on students 錄取 matriculating at the Academy's schools between 1864 and 1924; some from the last group are still practicing artists. 4 After analyzing the data with a computer, a pattern emerged, which, I imagine, applies also to other countries that share similar cultural traditions, some of which are rooted in antiquity. Moreover, I found many cases of women artists struggling, as it were, on two fronts, against both external and internal resistance. 先⾏者 THE FORERUNNERS The first Swedish woman artist who managed to support herself by her art was Ulrika Pasch (1735-96). Daughter of portraitist Lorens Pasch the Elder, she was trained by her father, assisting him in his workshop and copying his portraits. She did not marry, nor did her sister, Hedvig Lovisa; 嫁妝 their father could not afford dowries for them. Their brother, Lorens Pasch the Younger, was also trained as a portrait painter by the father; he, however, was sent to Copenhagen and Paris for further study, and stayed abroad for 15 years. Meanwhile, Ulrika kept house for her father and supported him with her portrait work when he grew too old and sick to paint. After his death she also supported her sister. She received many orders because her prices were low. When Lorens returned from Paris he settled with his sisters, he and Ulrika painting, Hedvig Lovisa keeping house. He became a portraitist at the Royal Court and a leader of the Royal Academy; he was also made Knight of the Wasaorder and granted a pension at public expense. Ulrika, 代⾔ with the endorsement of her brother and his friends, applied to Parliament three times for a similar pension, but without result. Instead, she was made a member of the Academy, an honor indeed, but one that cost the government nothing. 慣常的 It was customary for biographies to be written of the deceased members of the Academy, and that is why so much is known about Ulrika Pasch.5Otherwise she would have been forgotten, as were nearly all daughters of artists in Europe who, since antiquity, worked in anonymity in the family workshop, trained by and dependent upon a father, brother, or husband. When in the 18th century a middle class emerged in it adopted many features of noble life. Girls from Sweden,貴族 the aristocracy and nobility had, since the Renaissance, learned to draw and paint watercolors as part of their education; now these arts became part of the education of all 2 Woman's Art Journal FIG. 1. Amalia Lindegren, Sunday Afternoon in a Dalecarlian Farmhouse(1860),oil on canvas,87 x 116cm. NationalMuseumof Sweden,Stockholm.Photo:NationalMuseum. well-bred young women. Occasionally, some of them revealed talents above the ordinary and turned professional. This was so in the case of Amalia Lindegren (1814-91), also a portraitist, who had the extraordinary good fortune to study at the Academy's lower school, together with three other young women. 6They soon left the Academy, however, apparently because of bullying by the male students. Lindegren was granted a government scholarship-one of the few women so rewarded-for study abroad. She stayed for in Paris, first in the Cogniet five years-1850-56-mostly of the teaching there, studio for ladies, but, disapproving ⼯作室 transferred to Ange Tissier's atelier. She also made short visits to Duisseldorfand Munich and stayed a year in Rome, where she copied the old masters. 7On returning home she settled in the capital and supported herself-she never married-by painting portraits of royal, aristocratic, and intellectual personalities. She also executed genre paintings in the popular Dusseldorf style. Her most admired work, Sunday Afternoon in a Dalecarlian Farmhouse (1860; Fig. ⽥園詩般的 1), an idyllic scene of family country life, was bought by the state, hung in the National Museum, and became widely known through reproductions. 有利於 This painting, in fact, was used as an argument in favor of allowing women into the Academy's schools. In Sweden, as in other Western countries at the time, it was thought that women were unable to produce anything of value in the arts and sciences, as they were, by nature, passive, imitative, and dependent.8 This conservative view, however, began to be questioned by liberal opinion, which claimed the right of all individuals to develop their natural abilities freely, regardless of sex. Now that a woman had displayed artistic ability equal to a man's-which the state had admitted by purchasing Lindegren's painting-was it not fair then to give women access to the same training facilities as men? 9 But it was neither Amalia Lindegren's success nor liberal and feminist opinion that brought about the resolution carried in the Parliament in 1863, giving women access to the Academy's schools. Shifting social conditions-changes in age distribution and in the social groups, industrialization, and a lower incidence of marriage-had resulted in a surplus of unmarried women in the middle and upper classes. These women had to be given opportunities for vocational training so as to become self-supporting. Thus, the opening of the Academy's schools was one of the reforms 解放 introduced in the period 1845-80, which promoted the eman10 cipation of women in Sweden. 並不是因為單⼀個體成功、⾃由派、女性主義 使女性能夠享受教育權(藝術),⽽是因為中 產、菁英階級的離婚率上升。 RESULTS OF THE STUDY What became of the women students at the Academy? Did they manage to support themselves as independent artists and were they able to compete on equal terms with their male colleagues? The investigation points out several differences between male and female art students, in their conditions of study as well as work. From 1864 to about 1930 there were slightly more than half as many women students as men enrolled at the 上流女性 Academy, a result, no doubt, of the narrower recruiting base 才能學畫 for women. Most came from the upper and upper-middle classes, while the men were mainly recruited from the lower-middle class. Very few students of either sex had a working-class background. Of course, only well-to-do families could afford expensive educations for their daughters, and it was also primarily in the upper classes that the problem of unmarried women existed. The favorable socioeconomic conditions enjoyed by the women students explain why a higher proportion of them completed their courses at the Academy. But the difference was not very great. Fewer women actually took up professional work on comFIG. 2. AmandaSidwall,Self-Portrait(1870-71),oil on canvas,64 pleting their periods of study, however. The most likely x 53 cm. NationalMuseumof Sweden.Photo:NationalMuseum. 女:早早放棄,因為結婚 男:走更久,但因為學畫沒辦法維持⽣計 explanation is that a number of them married, abandoning further training and activity. More men than women practiced for a while as artists, participated in a few exhibitions, but then left the profession, seemingly because of difficulty in maintaining a livelihood. Taken together, these "terminations" are surprisingly evenly spread: about the same proportion of men as women students abandoned their profession, but at different times and apparently for different reasons. Easel painting was the predominant form of art activity for both men and women, often supplemented by drawing and/or graphic art. Most sculptors, however, were men. Female sculptors tended to produce small sculptures and handicraft products, which were easier to make and sell. Some women painters, too, changed over to applied art, ceramics and textiles, as well as miniature paintings, the last two being traditional female pursuits. None of these had the status of the fine arts, but competition was not as fierce in these markets.11 As for subject matter, there was a marked difference between the sexes. The number of men painting landscapes was more than twice that of women, while the opposite is true of portrait painting. Men retained throughout a marked preference for landscape painting. Women artists of the first 10-year period also painted genre subjects to a greater extent than did the men. The proportion of genre subjects declined for all students, but portraits continued to be the dominant subject among women artists until around 1910. Thus the women artists who continued to work into modern times were distributed fairly evenly among the different areas. This suggests that women now felt free to choose their subject matter. Almost half the men worked mainly as independent artists, but over half of them also had supplementary employment, mostly related to their artistic activities, working as teachers, illustrators, art critics, consultants, or museum officials. Of the women, 40%worked as independent artists, but 75%of them were involved in other activities, generally (since over half were married) looking after home and children. Women's opportunities for employment, both within and beyond the artistic sphere, were fewer and still restricted by social convention. Unmarried women were naturally the most active professionally. They were distributed among different fields of activity in much the same way as the men, but they seldom achieved the same recognition or status. With few exceptions, women artists generally married within their own social class, or they married artists. A marked difference can be observed between these two groups. The wives of artists were more active throughout the period. They had a stronger economic incentive, their surroundings provided more artistic stimulus, and through their husbands they came into contact with the institutions of the art world. The professional activities of the married women artists increased as time advanced, and this was paralleled by the increasing professional activity of married women as a whole from the 1930s onward. The real problems for the women seemed to arise when they wanted to compete in the open art market. There, competition was severe and the entry of women was disliked by the men just as was their entrance into other professions, especially when and where job opportunities were scarce. By Woman's Art Journal 3 tradition, men had contact with the art world as with professional life as a whole. While they ran the risk of failing totally as artists-in fact, many of them did-still they had a greater chance to reach the top. The women artists, being a new group, had difficulty infiltrating the art institutions which, of course, were dominated by men. Onthe other hand, their social safety net functioned better. Their roles as daughters or wives protected them from going under, but often prevented them from putting an all-out effort into their work. They ran the risk of remaining amateurs, and that was precisely what they were accused of being, rightly or wrongly. At the bottom lay the conservative view of women, which was held by many art buyers, critics, and dealers, and indeed sometimes by the women themselves. Their education did not encourage the qualities required for successful artistic pursuit: independence and self-confidence. Nor had they, like the men, inspiring models to imitate. They had to struggle against the disbelief of male artists, critics, and the general public, as well as against their own lack of selfesteem. THE DAUGHTER'S DILEMMA Amanda Sidwall (1844-92) was one of the first women students at the Academy. She was born into a wealthy family, and spent six years in the Academy and nine in Paris, where she studied with Tony Robert-Fleury at the Academie Julian. Robert-Fleury recognized her talent and encouraged her to send paintings to the Salon. Three-two genre subjects and a portrait-were shown in the Salons of 1877, 1881, and 1882. She also contacted two private dealers who agreed to sell her work. Sidwall's letters to her sister at this time express pleasure in her work and belief in her future: Now, I can say, that I have a future here, becausethese art-dealersare quiteinfluential.... I havealreadya certain reputationto maintain. ... Mydreamhas cometrue;I will live in Paris and go to Swedenfor vacations,but I am not producinganythingfor the Swedishpublic.12 Shortly thereafter her parents became sick and called her home. The dutiful daughter, she stayed on to help out, thus giving up the career that seemed to lie ahead. She continued to paint, mostly pastel portraits of her relatives and friends. From time to time she had her own studio and accepted female students, but she never exhibited. As she died rather young, it is difficult to say how her talent would have developed. Her situation was not unusual, however, as many of the Academy's first women students became "daughters living at home,"whose production is more or less hidden, since they seldom exhibited. Some did sell privately, but they ran the 枯萎 risk of withering away for want of adequate stimuli and criticism. Sidwall's Self-Portrait (1870-71; Fig. 2) shows a seriouslooking young woman painted in a manner that was for that time unusually broad and bright. Like countless other gifted women, Sidwall was given that ultimate compliment: she was told she was a real colorist, and painted in the broad manner of a man.13 Not all daughters were so loyal to their parents. About four decades later, in 1920, Signe Pettersson (1895-1982) came to Paris for art studies, not without some resistance from her father, a high government official. In 1922 she married a Swiss artist, Amad6 Barth, but was widowed four years later. About the same time her father became a widower, and he thought it convenient that his daughter should 4 . Woman's Art Journal CT'.-r ' . ..... _. FIG. 3. HannaPauli,BreakfastTime(1887),oil oncanvas,77 x 107 cm. NationalMuseumof Sweden.Photo:NationalMuseum. return home and keep house for him. Signe Barth lived a life of near poverty in Paris; at home she could have led a carefree, rather comfortable existence. She hesitated for a long time, but realized that as a daughter living at home, she would not be free to study and paint. So she stayed in Paris. 14 During the Depression when the art market in Paris worsened, Barth returned to Stockholm and in 1940 started a painting school for beginners. The school existed for about 20 years, and its success enabled Barth to lead an independent life. She painted and exhibited continuously, through the 1970s, mostly small landscapes, interiors, and still lifes that reveal her debt to Cezanne. A critic wrote of her work: 樸實無華 but solid "There is in her small paintings an unpretentious in concentration the essence of her she seeks quiet quality; vision." 5 On the board of the Swedish Artists' Union for more than 20 years, she was, for much of that time, the only woman. 16 ARTIST AND ARTIST'S WIFE For women artists who were the wives of artists-and there were many-there arose a special problem: should they compete with their husbands in the same field? In fact, most of the artist/wives directed their talents to adjacent domains, such as illustration, lithography, miniature painting, or textile art. In a few cases, husband and wife had equal status; for example, Georg Pauli and Hanna Hirsch and Sigrid Hjerten and Isaac Grunewald. Hanna Hirsch's (18641940) reputation as a gifted artist was secure when she met Georg Pauli in Paris in 1885. They married in 1887, returned to Sweden in 1888, and had three children. Their home in Stockholm became a gathering place for the city's cultural elite. Georg Pauli was a versatile artist, creative in many genres and styles; he also wrote pieces on art theory and criticism. Hanna was almost exclusively a portraitist and a very fine one, especially when she painted her family, her children, and her friends-Stockholm's artists, intellectuals, musicians, and writers.7 The work for which she is most famous is the large group portrait Friends (1900-07), done in the style of Rembrandt's group portraits. Another such painting is TheArt Committeeof TheFriends of Textile Art (1912-20), showing women committee members discuss突出 feature is the powerful ing a work of art. The most salient of the women's contrasting temperaments, which portrayal shows clearly the artist's capacity for character study. Hanna Pauli also painted scenes of domestic life and interiors. Breakfast Time (1887; Fig. 3) uses the old motif in a new way: the perspective with the large still life in the foreground and the too-small housemaiden in the background refers both to Japanese woodcuts and to camera angles. Although primarily a painter of values, the exquisite play of light over the scene clearly shows the influence of Impressionism. The critics, however, were sour; one of them asked if the artist had wiped her brushes on the tablecloth. Though Hanna Pauli lived for 76 years, her production was small. She was self-critical and worked slowly and hesitantly, exhibiting on her own only once, in 1923, when she was 57 years old. "Georg is a much better artist than I am," she wrote, 1but a contemporary critic disagreed: "She has held her position much better than her husband."19 Both Sigrid Hjerten and Isaac Grunewald studied in Matisse's Paris studio from 1909-11, and Sigrid (1885-1948) is said to have been Matisse's favorite pupil because of her introfine sense of color.20Upon their return home, they 前衛 duced Matisse's style to Stockholm, forming the avant-garde artist group The Eight in 1911, with Sigrid the only female member. 21Isaac, an extrovert with a charming and dominant personality, led the group. He was often involved in 論戰 polemics, for the new art encountered severe attacks from both critics and the public. Sigrid received her share of negative criticism, but was considered an imitator of her husband-and a poor one at that. View of Slussen (1919; Fig. 4) is a rather typical Swedish Matisse-Expressionist painting. It is a view of central Stockholm from her studio window. The buildings are easily recbut since they are put together in a seemingly ognizable, 任性的 capricious manner, with perspective distorted, the painting provoked both critics and the public. Colors are bright and strong: red and yellow against blue, warm against cold. The painting expresses the dynamic of city life, which the Matisse students preferred to the national romantic landscapes of the preceding generation. Gradually the Matisse Expressionists overcame critical and public resistance, and Isaac became one of Sweden's more celebrated artists. Sigrid did not receive as great a share of the fame, as she was still considered an echo of her well-known husband. Depressed, she withdrew from public life. She continued, for a time, to exhibit with her husband and in group shows, but had only one solo exhibition, in 1936. (Issac held his first one-man show in 1911.) Her depressions increased, Isaac divorced her in 1937, and from 1938 to her death 10 years later she was a patient in a mental hospital. In the early 1930s, before her illness became manifest, she had an outburst of productivity, creating more than 100 works in a visionary style, the forms dissolved in showers of intense colors, On exhibiting these works with Isaac in 1935, she received the usual negative reactions, but some of the critics now began to discern her merit. One wrote: Sigrid Hjertknis the greatestsurprise.Withher 100paintings from the last three years she occupiesthe big room totally. You will in vain search for a paintingof inferior quality.Comparedwith hers,the paintingsof Isaac Grinewald seem moreunevenin quality.22 Woman's Art Journal 回顧性的 After viewing the nearly 500 works in her 1936 retrospec⼀致的 歡呼 / 招呼 tive, the critics were unanimous: the exhibition was hailed as one of the most remarkable of the season and Sigrid Hjerten was honored as one of Sweden's greatest and most original modern artists. Thus, she gained recognition-but too late. BREAKTHROUGH AT 70 Two women artists, who gained recognition late in their lives were Eva Bagge (1871-1965) and Esther Kjerner (18731952). They were companions in the Academy's schools and on many study trips in Europe; they shared a home and studio in Stockholm for about 50 years. Bagge specialized in genre subjects and interiors, Kjerner in still life and floral motifs. They participated in group exhibitions in the capital as well as in the provinces, but their works, sometimes refused, sometimes badly hung, did not draw the critics' attention until an art dealer arranged one-woman shows for each of them in 1941, when they were about 70 years old.23 Suddenly, they were "discovered," but by that time their motifs and styles were rather old-fashioned. Their realism and refined sensibilities were overwhelmed by the modernism that had by then taken hold in Sweden. To draw attention to one's work, it is still necessary for an artist to have a one-person show. Why did women artists do this so seldom? Probably due to lack of confidence and fear of being attacked by the critics. Eva Bagge, for instance, when asked why she had not exhibited solo before, answered: "If you love your work, you are afraid that scathing criticism will spoil your zeal."24 The circumstances surrounding the careers of Sigrid Hjerten, Eva Bagge, and Esther Kjerner probably made critics more willing to consider women's work. And as women's confidence and professional activity increased, most broke with the tyranny of genre. They introduced new motifs into their art, were identified with new art movements, and by the 1940s began to receive positive critical and public response. They were also supported by feminist periodicals and unions, and organized to be better represented in exhibitions. 5 selling infrequently. Nevertheless, she attracted critical attention and was one of the few women artists invited to join the artist group Phalanx (1922) and its successor, Form and Color (1932).2She was appointed a member of the Academy in 1954.29 Siri Derkert (1888-1973) became a member of the Academy in 1960. She and Vera Nilsson were recognized artists and could plead the cause of women in this male preserve. Both were single parents forced to provide for their families by their work. Like many other women artists, they painted their children. However, they portrayed them without sentimentality, often emphasizing the child's clumsiness and helplessness, even its homeliness. Although paired, their work was quite disparate; Derkert, the more disharmonious, constantly experimented with techniques, developing from Fauve surface painting to analytical then back to a personal form of Cubism, to Expressionism, 致⼒於 Cubism. Deeply committed to the feminist movement as well 重新武裝 as to protests against rearmament and environmental pollution, Derkert expressed her opinions in her monumental works. She and Nilsson were commissioned in 1956 to decorate two pillars in Stockholm's central metro station. Nilsson depicted city motifs in colored mosaics, while Derkert carved into the concrete the faces of feminist pioneers, anonymous women workers, and a girl carrying the "dove of peace." It is appropriately called Woman Pillar (Fig. 6). In her 80s, Derkert designed two other wall decorations, a metal sculpture, and cartoons for two Gobelin tapestries, all with the themes of peace, freedom, and a clean environment. She used carved and colored concrete, collage of metal 25 THREE MODERN ARTISTS Vera Nilsson (1888-1978) is considered Sweden's most important Expressionist.26Her form is explosive, her colors intense, her work tender when depicting a child's fragility or excited and pathetic when turning the Swedish landscape, traditionally depicted as idyllic, into a symbol of doom. She did not leave the old genres, she merely gave them new content. She also turned her considerable talent to political art: MoneyAgainst Life (1938; Fig. 5), a monumental work, was painted during the Spanish Civil War and has been called "a Swedish Guernica." It is a protest against war, symbolized by the central black tank smashing all life in its way. The faceless men standing upon it, high-hatted and dressed in black, represent the war industry, its links with financial powers symbolized by the bills and stock certificates floating in the air. Crowds of soldiers, crying women, children's corpses, their expressive gestures distorted in agony, fill the painting. Only a small boy in the foreground rises to defy the machinery of war. The colors are strong, the forms distorted-and the public was shocked. The painting was purchased by the state for the Culture House of Skovde in 1964. Nilsson lived a simple, withdrawn life, 2exhibiting and FIG. 4. Sigrid Hjerten-Griinewald, View of Slussen (1919), oil on canvas, 108 x 90 cm. Museum of Modern Art, Stockholm. Photo: National Museum. ..... . , Woman's Art Journal 6 r+srM'; "'! :|\''5j~ ; :' *,, :' ','' - ,,: - $ _ ,;: - n i e - : 3. ~ *'f - v X,...I "L,t - Ii V7, . 5. Vera Nilsson, M<ey Against Life(1938), 400x 600c.m.Photo:"H.Doverholm. ~?FIG. "I; plates, and carvings. She made reliefs out of strings of stainless steel, which on the wall.Neverbeforehad she bentandformedto createchanging.shadows Lundgren (1897-1979) studied painting, sculpture, and ceramics, her even- theGustaLife (1938),400x 600 .m. Photo:H. Doverhom. beFIG. 5. VeraNilsson,MoneyAgaingconditionst studied in Sweden and Europe. Since she never tual married, specialty,wherever andshe and worked she chose. She designed glass in Finland Germany;. which plates, of sta iness Swedene, andcarvings.monumental buildstrings stoneware reliefs to decorate public worked in the Arabia porcelain factories in Finland, and in ,Sevres, .,France; !-'\ i,' hasformed the largest carvng rock shadows ing in thEurope power plantd/ Stone Age,ntand wall. NevThe so boldly a Sw artist has edishwo been there since 1940. ... the mateural uses man her studios, works, and friends in Europe, ^;?; .~ ;.international recognition,led.to her beinggrantedfavorable working c onditionsat theGustafsberg factoriesin . S he large-scale polychrome stoneware sculpture Sweden began producing andmonumental stoneware reliefs to decoratepublic buildings in Sweden \: "- ,' * J v '.t ;,.:l ^, v1' ^/t. r *t* . ? *1.. the Gustafsberg factories | f.1,i, ^?" ,. . ' s .. .... T N :) -i at . ..' ' . ...^ > - :' /"AJ ??, 1~,.! ,'..':-' '~-;'.. elbarovconditions af ;'I _ Yt _ ':.t..-1 ,X . .. '* ' ,. C ? hasbeent.ere.since. wh-.i.house the,mural , gnieb dworking etnarg :. .t. in /I \ ';:'? :--, - :: -!S:!J F'1~~~~~~~~~~~~' -?,:' o ?:;.Y ' .~.~.': Sweden, S:. . '.du . i~'~ ".lag-cl ~yhoestnwrcltr :;,......:t?~cI ,orked Arabia inthe porcelainfactoriesin Finland,andin S~vres,France; r"~f~~JX e~l~j ~ ''. .~ .:T: ' :. --~dios, ,orks,,,dfriends in Europe, her international recognition led to her U '"" '- "' 'slg.^ 'V,- ' ,:~. e'X"":' "a" ' Xfc-pj^f K^BMBIP'^jyFIG. 7. Tyra Lundgren, History of theRiver (1950), polychrome stoneware relief, 7.5 x 4.8 m. Namforsen Power Station, Angermanland. Photo: Tyra Lundgren, Ett liv i konst (1978). FIG. 6. Siri Derkert, Woman Pillar (1956-58), carved concrete, Stockholm Central Metro Station. Photo: Rolf Soderberg, Siri Derkert (1974). Woman's Art Journal Tyra Lundgren exhibited collectively and singly all over the world and is represented in Swedish, European, and American museums. In her last retrospective exhibition, held in Stockholm in 1978, she exhibited 40 paintings from 1920 to 1939, including a series of 15 self-portraits, none of which had been shown before because of the artist's selfdoubts. 32Even this highly successful artist was not free of woman's pervasive scourge: lack of self-confidence. ? 無孔不入、無處不在的禍害 1. About 30 artist groups based on the European model were formed in Sweden during this period. They varied greatly regarding the number of members, longevity, art style, and influence on art policy. For instance: the school of Smedsudden was naivistic, that of Goteborg coloristic, the Halmstad group surrealistic, etc. The Phalanx dominated art politics in the 1920s;it was replaced by Form and Colorin the 1930s, which worked practically for exhibitions and sales, and ideologically for social engagement in art. 2. Anders Zorn visited the U.S. several times, painting President Cleveland and industrialists Adolphus Busch and James Deering. 3. For instance: Sixten Strombom, History of theArtist's Union 1-2(Stockholm: Albert Bonnier, 1945, 1965) treats exhaustively (1000 pages) the male artists cited, but has little to say about the women. Hanna Pauli, for example, was at one point vice-president. The Dictionary of Swedish Artists 1-5 (Malmo: Allhem, 1952-67) has biographical data of artists active throughout Swedish history. Here too the treatment of women is less detailed. 4. Ingrid Ingelman, WomenArtists in Sweden: A Study of the Students Matriculating at the Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, 1864-1924, Their Recruitment,Education and Activity (University of Uppsala, 1982). 5. Thure Wennberg, "To the Memory of Ulrika Fredrika Pasch." Documents of The Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm, 1798. 6. The others were sisters Jeanette and Josephine Holmlund and Lea Lundgren. Jeanette Holmlund (1825-72) studied genre painting with Vautier in Paris between 1851-54,and taught a class of women students in Stockholmfrom 1854-60. She married Norwegian artist Niels Moller and moved to Dfisseldorf in 1860, where she painted genre subjects in a style similar to Lindegren. Josephine remained unmarried and joined her sister and brother-in-law in Dusseldorf in 1863. She painted landscapes, Norwegian and Swedish fields and streams, archipelagoes, and idyllic scenes. Lea Lundgren was the daughter of Ludvig Lundgren, an engraver of coins and medals. She was instructed by her father and succeeded him-for want of a qualified male candidate-and thus became the first woman in the service of the Swedish state; Dictionary of Swedish Artists. 7. Eva-Lena Bengtsson, "Amalia Lindegren"(B.A. seminar paper, Institute of Art History, University of Uppsala, 1979). 8. Asta Ekenvall, Male and Female: Studies in the History of Ideas (Archive for Women'sHistory, 5, Malmo:Gumpert, 1966),has traced the roots of these pervasive ideas back to the philosophers of antiquity. Based on a misunderstanding of the sexual act-the female ovum was discovered first in 1827-it was taken for granted that man created life, woman only received and cared for the manly seed. Thus the analogy between sexual creativeness and intellectual creativeness: as man is creative in sexual intercourse, it is he alone who is creative in art, science, and social life. Womencould only receive ideas. This theory both explained and legitimatized existing sexual roles. 9. The feminists were fully aware that women were not formally excluded by the constitution of the Academy; the very notionof training women to be artists was completely foreign to the Academy's founders. 10. The Swedish Academy was the second in Europe to give women access; the first was the English Royal Academy (1861). 11. In 1917, young women artists were advised to go over to applied art, since there were far too many painters already in the Swedish market; Ellen Jolin, "Thoughtson Exhibitions," Hertha (Stockholm, 1917), 140. 12. Quoted from Amanda Sidwall's letters. Archives of the National Museum, Stockholm. 13. Ibid. 14. Interview with Signe Barth, Stockholm, November 24, 1974. 15. Tord Baeckstrom, "Women Artists," Goteborgs Handels- och Sjifartstidning, December 13, 1952. 16. The Swedish Artists' Union was founded in 1890 as an alternative to the 7 1886 Artist's Union. It was meant to include all active artists and accepted women artists but it was not until the 1940sthat a woman was admitted to its board. 17. Information on Hanna Pauli can be culled from biographies, diaries, letters, memoirs, and reviews, but a monographhas yet to be written. A B.A. seminar paper on Hanna Hirsch Pauli (1979) written by Lena Soderlund is at the Institute of Art History, University of Uppsala. 18. Quoted from Hjalmar Lundgren, My Remembrance-Book(Lindblads: Uppsala, 1950), 105. 19. Quotedfrom an art review signed G.T., in Skanska Dagbladet,October 10, 1933. 20. Four colleagues of hers have given witness; quoted in Birgitta Berg, "Sigrid Hjerten: A Swedish Pupil of Matisse" (B.A. seminar paper, Institute of Art History, University of Uppsala, 1983). 21. Women artists seldom were invited to join the artist groups formed in Sweden during the first half of the 20th century unless, like Sigrid Hjerten, they were connected with male group members. Nor were lone women invited to join the avant-garde artist groups forming in other European countries during this period. See Lea Vergine, et al., L'altra metd dell'avanguardia 1910-40 (Milano: Gabriele Mazotta editore, 1980), Swedish translation: Andra hdlften av avantgardet 1910-40 (Stockholm:Bokomotiv, 1981), with a supplement by Anna-Lena Lindberg and Barbro Werkmaster,"Kvinnori svenskt avantgarde 1910-40" ("Womenin the Swedish Avant-garde 1910-40"),290-93. 22. Martin Stromberg, "TheGriinewald'sExhibition," GoteborgsMorgonpost, October 10, 1935. 23. The art dealer Gosta Stenman had moved to Stockholm from Finland, where he had succeeded in launching another neglected woman artist, Helen Schjerfbeck, now enjoying a growing reputation. After their successes, two books on the artists were issued by Nordic Rotogravyrin Stockholm: Gerda Boethius, Eva Bagge's Art (1944) and Otto G. Carlsund and Marita Lindgren-Fridell, Esther Kjerner'sArt (1943). 24. Interview with Eva Bagge, Svenska Dagbladet, November 7, 1941. 25. In 1884 the first women's union was formed taking its name from the Swedish feminist writer Fredrika Bremer. Since 1914 the Fredrika Bremer Union has edited Hertha, a review named after a novel by this author. From 1911-18 three women edited the periodical Art, which gave support to women artists. The Union of Swedish Women Artists was founded in 1910,and still exists. Its aim has been to further women's art and economic interests. 26. Noted in the Dictionary of Art, 1-3 (Nordic Dictionaries Inc., 1958), which has a rather long and respectful article on her, as well as shortcr notices of all the women artists mentioned here. Handbooks such as Gosta Lilja, Swedish Painting in the 20th Century (Stockholm: Wahlstrom & Widstrand, 1968)deal with Derkert, Hjerten,and Nilsson. Rolf Soderberg, Siri Derkert (Sweden's general art union's publication, LXXXIII, Stockholm, 1974)is the only monographof a woman artist in a long series of artist biographies. Monographson Sigrid Hjerten, Tyra Lundgren, and Vera Nilsson remain to be written. 27. For about 50 years she lived in an outmoded flat, which was also her studio, and made her monumentalworkson the floor. Knowingfrom her own experience the vital importance of a studio, she worked to provide young artists with studios in Stockholm; Artist's Studio (Catalogue, House of Culture, Stockholm, 1981). 28. She did not stay with these groups very long as the obligation to exhibit regularly did not suit her working pace; Lena Hovelius, "Vera Nilsson (B.A. seminar paper, Institute of Art History, University of Uppsala, 1972). 29. Before this year, no Swedish woman artist had been appointed an Academy member since 1889, when a portraitist of ordinary quality, Hildegard Norberg, was asked to join. Archives of Swedish Academy of Fine Arts. 30. Tyra Lundgren, "A Life in Art" (Catalogue, Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm, 1978). 31. In the 1940s and 1950s she executed 13 large-scale polychrome stoneware reliefs; for example Famous Womenin SodermalmGirl'sLyceum, Stockholm; and Life Survives, in the entry hall of the South Hospital, Stockholm. 32. Maj Modin, "Tyra Lundgren's Self-Portraits" (B.A. seminar paper, Institute of Art History, University of Uppala, 1977). INGRID INGELMAN received her Ph.D. from the University of Uppsala in 1982. She has worked as a journalist and a teacher.