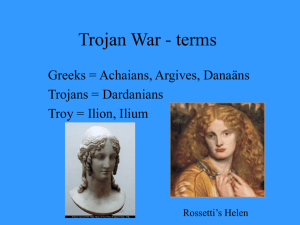

Mythology Background and Plot Summary .By Michael J. Cummings...© 2003 . Mythology Background .......In the ancient Mediterranean world, feminine beauty reaches its zenith in Helen, wife of King Menelaus of Greece. Her wondrous face and body are without flaw. She is perfect. Even the goddess of love, Aphrodite, admires her. While Aphrodite competes with other goddesses in a beauty contest–in which a golden apple is to be awarded as the prize–she bribes the judge, a young Trojan named Paris. She promises him the most ravishing woman in the world, Helen, if he will select her, Aphrodite, as the most beautiful goddess. After winning the contest and receiving the coveted golden apple, she tells Paris about Helen and her incomparable pulchritude. Forthwith, Paris goes to Greece, woos Helen, and absconds with her to Troy, a walled city in Asia Minor (in present-day Turkey). .......The elopement is an affront to all the Greeks. How dare an upstart Trojan invade their land! How dare he steal the wife of one of their kings! Which Greek family would be next to fall victim to a Trojan machination? Infuriated, King Menelaus and his friends assemble a mighty army that includes the finest warriors in the land. Together, they cross the sea in one thousand ships to make war against Troy and win back their pride–and Helen. But the war drags on and on. Weeks become months. Months become years. Years become a decade. It is in fact in the tenth year of the war that Homer picks up the thread of the story and spins his tale, focusing on a crisis in the Greek ranks in which the greatest soldier in history, Achilles, decides to withdraw from battle and allow his fellow Greeks to fend for themselves. It is Achilles who is the central figure in The Iliad. .......Homer begins with a one-paragraph invocation requesting the Muse (a goddess) to inspire him in the telling of his tale. Such an invocation was a convention in classical literature, notably in epics, from the time of Homer onward. ..... Plot Summary . .......Ten years have passed since the Greek armies arrived in Asia minor to lay waste Troy and win back their honor. Yet in all those years, neither side has gained enough advantage to force a surrender. The Greeks remain encamped outside the walls of the city, their nighttime fires mocking the glittering firmament while their generals plot stratagems and their warriors hone weapons. .......Among the Greek leaders, bloodstained and hardened to war, are Agamemnon, the commander-in-chief; Menelaus, King of Sparta and brother of Agamemnon; Odysseus, king of Ithaca and a military genius of unparalleled cunning; and Aias the Great, a giant warrior of colossal strength. With sword and spear, with rocks and fists, the Greeks have fought the Trojans–led by the godlike Hector, their mightiest warrior, and Aeneas, a war machine second only to Hector on the Trojan side–to a standoff. In time, the Greeks believe, they will prevail. They have right on their side, after all. But even more important, they have Achilles. He is the greatest warrior ever to walk the earth–fierce, unrelenting, unconquerable. When Achilles fights, enemies cower in terror and rivers run with blood. No man can stand against him. Not Hector. Not an army of Hectors. .......But, alas, in the tenth year of the great war, Achilles refuses to fight after Agamemnon insults him. No one can offend the great Achilles with impunity. Not even Agamemnon, general of generals, who can whisper a command that ten thousand will obey. The rift between them opens after Agamemnon and Achilles capture two maidens while raiding the region around Troy. Agamemnon’s prize is Chryseis, the daughter of a priest of the god Apollo. For Achilles, there is the beautiful Briseis, who becomes his slave mistress. When Chryses, the father of Chryseis, offers a ransom for his daughter, Agamemnon refuses it. Chryses then invokes his patron, Apollo, for aid, and the sun god sends a pestilence upon the Greeks. Many soldiers die before Agamemnon learns the cause of their deaths from the soothsayer Calchas. Unable to wage war against disease, Agamemnon reluctantly surrenders Chryseis to her father. .......Unfortunately for the Greeks, the headstrong king then orders his men to seize Briseis as a replacement for his lost prize. Achilles is outraged. But rather than venting his wrath with his mighty sword, he retires from battle, vowing never again to fight for his countrymen. On his behalf, his mother, the sea nymph Thetis, importunes Zeus, king of the gods, to turn the tide of war in favor of the Trojans. Such a reversal would be fitting punishment for Agamemnon. But Zeus is reluctant to intervene in the war, for the gods of Olympus have taken sides, actively meddling in daily combat. For him to support one army over the other would be to foment celestial discord. Among the deities favoring the Trojans are Ares, Aphrodite, Apollo, and Artemis. On the side of the Greeks are Athena, Poseidon, and Hera–the wife of Zeus. There would be hell-raising in the heavens if Zeus shows partiality. In particular, his wife’s scolding tongue would wag without surcease. But Zeus is Zeus, god of thunder and lightning. In the end, he well knows, he can do as he pleases. Swayed by the pleas of Thetis, he confers his benisons on the Trojans. .......However, when the next battle rages, the Greeks–fired with Promethean defiance and succored by their gods–fight like madmen. True, their right arm, Achilles, is absent; but their left arm becomes a scythe that reaps a harvest of Trojans. Aias and Diomedes are especially magnificent. Only intervention by the Trojans’ Olympian supporters save them from massacre. Alas, however, when the Trojans regroup for the next fight, Zeus infuses new power into Hector’s sinews. After Hector bids a tender goodbye to his wife, Andromache, and little boy, Astyanax, he leads a fierce charge that drives the Greeks all the way back to within sight of the shoreline, where they had started ten years before. Not a few Greeks, including Agamemnon, are ready to board their ships and set sail for home. Such has been the fury of the Hector-led onslaught. .......Then Nestor, a wise old king of three score and ten, advises Agamemnon to make peace with Achilles. The proud commander, now repentant and fully acknowledging his unjust treatment of Achilles, accepts the advice and pledges to restore Briseis to Achilles. When representatives of Agamemnon meet with lordly Achilles, the great warrior is idly passing time with the person he loves most in the world, his friend Patroclus, a distinguished warrior in his own right. Told that all wrongs against him will be righted, Achilles–still smoldering with anger–spurns the peace-making overture. His wrath is unquenchable. However, Patroclus, unable to brook the Trojan onslaught against his countrymen, borrows the armor of Achilles and, at the next opportunity, enters the battle disguised as Achilles. .......The stratagem works for a while as Patroclus chops and hacks his way through the Trojan ranks. But eventually Hector’s spear fells brave Patroclus with no small help from meddlesome Apollo. The Trojan hero celebrates the kill with an audacious coup de grâce: He removes and puts on Achilles’ armor. Grievously saddened by the death of his friend and outraged at the brazen behavior of Hector, wrathful Achilles–with a new suit of armor forged in Olympus by Hephaestus at the behest of Achilles' mother, Thetis–agrees to rejoin the fight at long last. .......The next day, Achilles rules the battlefield with death and destruction, cutting a swath of terror through enemy ranks. Trojan blood mulches the fields. Limbs lie helter-skelter, broken and crooked, as fodder for diving raptors. Terrified, the Trojans flee to the safety of Troy and its high walls–all of them, that is, except Hector. Foolishly, out of his deep sense of honor and responsibility as protector of Troy, he stands his ground. In a fairy tale about a noble hero with an adoring wife and son, Hector would surely have won the day against a vengeful, alldevouring foe. His compatriots–and the gallery of sons and daughters and wives peering down from the Trojan bulwarks–would surely have crowned him king. But in the brutal world of Achilles–whose ability to disembowel and decapitate is a virtue–Hector suffers a humiliating death. After Achilles chases and catches him, he easily slays him, then straps his carcass to his chariot and drags him around the walls of Troy. Patroclus has been avenged, the Greeks have reclaimed battlefield supremacy, and victory seems imminent. .......However, old Priam, the King of Troy and the father of Hector, shows that Trojan valor has not died with Hector. At great risk to himself, he crosses the battlefield in a chariot and presents himself to Achilles to claim the body of his son. But there is no anger in Priam's heart. He understands the ways of wars and warriors. He knows that Achilles, the greatest of the Greek soldiers, had no choice but to kill his son, the greatest of the Trojan warriors. Humbly, Priam embraces Achilles and gives him his hand. Deeply moved, Achilles welcomes Priam and orders an attendant to prepare Hector's body. To spare Priam the shock of seeing the grossly disfigured corpse, Achilles orders the attendant to cloak it. Troy mourns Hector for nine days, then burns his body and puts the remains in a golden urn that is buried in a modest grave. (The Iliad ends here.)