Guides and Knowledges Reviews - 2011.pdf - Utila Dive Centre

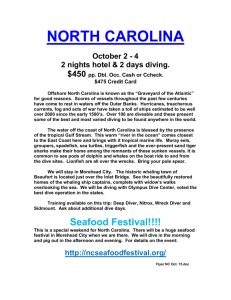

advertisement