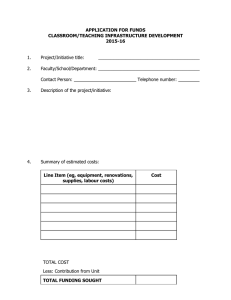

CHINA’S DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION MANSI MATE A 7075 MARWA SHERZAD A 7077 SUMAN SURESH B 7234 YASHODHARA THORAT B 7253 PRAPTI MOHANTY D 7837 ___________________________________________________________________________ RESEARCH SUPERVISOR: Uday Sinha A Project Submitted in the Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelors of Arts In Economics (2016-2019) DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS FERGUSSON COLLEGE (AUTONOUMS), PUNE. Examiner’s Certificate This is to certify that the project titled ‘China’s Demographic Transition’ submitted by students, Mansi Mate, Suman Suresh, Yashodhara Thorat, Prapti Mohanty, Marwa Sherzad have been assessed and graded towards the Partial fulfilment of the degree of B.A. Economics in the academic year 2018-2019. __________________________ (Signature) Name of Internal Examiner: _______________________________________________________________ _________________________ (Signature) Name of the External Examiner: ________________________________________________________________ Date: Time: Place: Table of Contents ABSTRACT............................................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDMENT .......................................................................................................................... iii ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................... Ошибка! Закладка не определена. CHAPTER: 1 ......................................................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER: 2 .......................................................................................................................................... 3 LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER: 3 .......................................................................................................................................... 7 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER 4 ......................................................................................................................................... 11 PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS ................................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER: 5 ........................................................................................................................................ 13 CONCLUSION: ................................................................................................................................ 13 RECOMMENDATIONS: ................................................................................................................. 13 FUTURE SCOPE: ............................................................................................................................ 14 REFRENCES ........................................................................................................................................ 15 ABSTRACT This paper analyses and explains the effects of the demographic transitions due to the “One Child policy” introduced by the Chinese government in the year 1979. This paper elaborates on the consequences of the 35-year long policy implications on Household savings, Capital investment, Gross fixed capital formation and Government expenditure on research and development. It studies the increase in capital productivity and total factor productivity contrary to the decline in surplus labour and the decline in the labour productivity in later years. Despite the weakening of the labour participation, the Chinese enterprises still had an edge on the technological advancements. The lack of efficient labour saw rise in the mobility levels from rural sector to the industrial sectors, thus having an increase in the capital allocation. ii ACKNOWLEDMENT Our research would be incomplete sans the mentorship of Uday Sir. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to him for providing his invaluable guidance, time, comments and suggestions throughout the course of the study. Our study was one that involved the exploration of complex variables and their integration and inter-linkage to arrive at the conclusion. The obtaining of this data from authorised sources was critical and a challenging yet thoroughly enjoyable task. A lot was learnt about the demographics and economic growth of the said country and we were provided with key insights on how to further study variables of other nations, if required in the future. It would be unfair to not acknowledge and thank Fergusson College and our professors for giving us the freedom to work on the vast topic that we chose and simultaneously helping us through the ups and downs of research. It was nothing but a pleasure to conduct this study. iii CHAPTER: 1 INTRODUCTION Statement of the problem: This study deals with the demographic transitions and the introduction of the “One Child Policy” in China, and studies if these policy changes affect the surplus labour and productivity of the country. To study this, we have explored factors including the saving, investment and capital formation patterns of the country, as also the total factor productivity. The research and development have also been taken into consideration. Purpose of the study: The “One Child Policy” was an interesting introduction to China’s policy framework. Following this, it was observed that there was a decline in China’s surplus labour. On the contrary, there was a simultaneous increase in the productivity levels of the country. The paradoxical nature of this phenomenon is what is intriguing and caused this study to be undertaken. It was also observed that there was a decline in the growth rate. The complex nature of this situation caused the study of the inter-linkage of these factors and its effects on the growth and development levels of China. Research question: Has China’s Demographic Transition and its One Child Policy led to a decline in its surplus labour and productivity? Significance of the study and treatment of the data: In a country, the changes in its Demographic patterns have direct implications on its economy. Such changes in the age structure are particularly significant in large and populous countries such as China. China has been experiencing drastic population changes over the past few decades. Previous governments had encouraged people to have more children believing that it would increase their labour workforce and growth rate. However, during 1970s, the new Chinese government introduced number of measures to reduce birth rate and slow down population growth. And thus, introducing the most controversial family planning scheme "One Child Policy" in 1979, limiting one third of the population to have only one child which prevented more than 400million births. Everything seemed to run smoothly over the years, however in 2011 the Old Age Dependency Ratio peaked and hence in 2015, the One Child Policy was officially removed. The Lewis Turning Point also caused a migration of labour from the agricultural to industrial sector. As a consequence, there was an increase in the labour productivity of the nation. These are the primary highlights of the study. 1 According to the data that we have generated, our first variable i.e. the Old Age dependency ratio of China has been increasing since the implementation of One Child Policy. On the other hand, the young age dependency ratio is decreasing. Due to the dependency structure, our second variable i.e. the Savings-Investment balance is on a rise. The third variable and the fourth variables that we are looking into, the GFCF and the expenditure on R&D are also on a rise. The working population has been dropping significantly since the implementation of the policy, owing to the decrease in labour productivity. To nullify this phenomenon, China has been investing in the improvement of Capital Productivity by focusing on capital formation. The Chinese government has increased its expenditure on the Research and Development to boost its technological progress. However, with the removal of One Child Policy in 2015, it is evident that the young dependency ratio is increasing. Method of procedure: The method of study was chiefly the collection and usage of secondary data. To do this, we collected information from secondary sources like: · · · · The World Bank OECD China’s Statistical Year book, 2017. Economic survey of China. We are trying to study the trends in the levels of Savings, Investment, Labour Productivity and finally the Total Factor Productivity during the period of Demographic Transition years i.e. 1982 to 2016. We are focusing on the Qualitative reasoning of the research. Limitations: An important limitation in carrying out the study was the retrieval of data. The frameworks regarding data privacy and statistics are very stringent in China, as they give utmost priority to data leakage circumstances and have strong legal policies backing the same. Thus, obtaining data for the study from authorised sources on the Internet was a crucial task. Another minor setback was collecting data from different periods of study and different research papers and conceptualising it into a review that represents and evaluates all time periods, so that there is no missing out on any factors studied during any time. The overview of the proposal helps us to conclude our remarks on the Demographic structure of China and its implications on the few mentioned variables of Productivity. The Proposal and the data mentioned in it clearly suggest that China can climb on the value chain by focusing more on higher productive activities through technological advancements and innovation. 2 CHAPTER: 2 LITERATURE REVIEW: (Stratford & Cowling) in their study found that income has been a key factor in determining the household consumption and savings behaviour in China. If the propensity to consume and propensity to save of the households differs with income, then the aggregate consumption and savings at any point of time will depend on the distribution of income. The changes in the income pattern/distribution of the households over a period will affect the growth of aggregate consumption and savings, relative to if the income distribution remained unchanged. Over the past 20 years, China’s real household income has seen an annual 10% rise in the growth rate however this drastic growth has been accompanied by a rise income inequality. The Gini coefficient index of China rose from 0.3 in the 1980s to 0.5 in the mid-2000s. Since 2009, the Gini coefficient has declined a little but yet remains among the top quintile worldwide. The rise in inequality of incomes has not led to a stagnation of income in the poorer households, but has been due to the richer households having a stronger income growth. The World Bank has estimated a decline in the proportion of Chinese living in poverty from 67% in 1990 to 11% in 2010. The impact of the distribution of income affecting the level of aggregate consumption has additional effect on the composition of aggregate consumption. The growth of Chinese household consumption has been significantly strong, averaging to 9% per annum, given the increase in China’s aggregate saving rate over twenty years. This level of growth is very drastic in comparison to other economies. (Jianguo & Zhang, 2017) wrote on the share of GFCF to GDP increased from 33.8% in 1998 to 45.3% in 2014. High Investment has led to High economic growth in China. The rate of return on capital hiked up to 30.5% in 2011, hence there was sturdy Investment. Increase in saving rate has led to increase in Investment. For rate of return on capital approach (Bai et al and Lu et al; 2014) macro approach which estimated for enterprise and secondary sector was stable while micro approach estimated individual enterprise for total rate of return and total profit was U-shaped. It was found that the Industrial rate of return was greater than secondary sector rate of return. The rate of return on industrial enterprise has played a major role in china's economic growth. There was higher rate of return due to rural-urban migration and capital investment. FDI and international trade have led to market competition and technological progress, contributing to TFP and labour migration. FDI however, can increase or decrease rate of return on capital. Positive externalities had been created by rapid infrastructure investment since 1990s contributing to the rate of return on capital in China whereas lack of infrastructure increases costs and brings down development. The efficiency of government consumption of public services e.g. health and education has gone up. China has a large share in corruption hence bureaucrat actions can have a negative effect on Investment. Using Regression results the paper found TFP to have a positive effect on rate on return on capital. The variables used were the TFP, secondary sector enterprise share, capital-output ratio, real interest rate and financial deepening. Secondary sector enterprise had a positive impact on rural-urban migration; capital-output ratio and financial deepening had a negative impact on rate of return. From 1998-2013, the rate of return increased, Investment increased along with TFP. Since 3 2011, there was a decline in rate of return and also Investment due to increase in lending real interest rate. (Knight & Ding , July 2009) In his paper analysis the supply and demand for Investment in China with increase in Investment-output ratio and inventory accumulation. In 1998 rate of return on privately controlled industrial enterprise (10.2%) was greater than state-controlled enterprise (4.8%) but it increased in 2013 to 15.0% and 10.2% respectively. Boost in rate profit on existing capital had created an expectation of higher profits on new investment. The main target of the china's state-controlled enterprises was to maximize investment growth and output. Investment demand increased when China opened o WTO in 2001, whereby the profits went up by expanding export, this was the reward for investment. There were also informal sources of security to create investor confidence and less government interference. Supply sideThe savings were made up of enterprise, household and government savings. National saving rate has increased for which household's saving has been a major source. Households with son seemed to save more than the ones with daughters. One child policy with minimum social security benefits led to increase in rural household savings. Private firms rely on their savings to invest hence savings have been high due to higher profits. Government savings had also increased since 1978 as the government chose financial investment over consumption. It was found that enterprise private invested more than they saved and households saved more than they invested. The ratio of GFCF increased from 36% to 42% from 1998-2007, increase in national income from 27% to 37%. Therefore, increase in investment was funded through redistribution of income from wages to profits. Private sector funded investment from their profits left or other informal sources at a high cost whereas the state sectors were given easy bank loans at low interest rates. Foreign firms had favourable licensing policies than the ones domestic private firms had to confine with which decreased their profit levels. Increase in capital accumulation would have led to a decline in marginal productivity but not happened so in China. Both investment and marginal productivity have been on a rise. Alongside Human capital and compulsory basic education had contributed to increase in economic growth. (Avuk, Benkova , & Vojtka , May 2012) One child policy by the People’s Republic of China brings out a huge change in the socioeconomic status of the country. This brings out enormous change in the economy of whole country which also has its effect in the world’s economy. This policy has its own pros and cons in the present and future. One of the major advantages of this policy is that it helps in reducing the population of china which is increasing in an alarming rate leading to unemployment, scarcity of resources, environmental threats and poor standard of living. Due to single child the economic and social condition of the family improved, the individual savings rate increased which results in better standard of living as there is no need for dividing the wealth among progeny. As the competition gets reduced the unemployment problem also gets reduced. Due to this policy the people are getting rich before getting old. There will be reduced demand on natural resources. It will have the availability of cheap labour which leads to low cost production. On the other hand, The One Child Policy had reduced the population of younger generation and the population is aging rapidly. The productive labour is decreasing at the same time government must provide pension for more pensioners. There will be fluctuation of price for the goods manufactured in China due to consolidation. Financial inflow is shrinking. In future 4 the One Child Policy will lead to have lowest dependency ratio. We may realise in future how sustainable and proactive the policy is and what effect it made to the welfare of its citizen and their economy. (Ozyurt, Total Factor Productivity growth in the chinese Industry, 2005), has described China has seen rapid industrialization in the recent decades and how it has grown as an economy in terms of productivity. He uses the parametric approach to support his data. This paper points out the various reasons which lead to the industrialization. The major reason was reallocation of resources and productive factors. The paper illustrates the increase in capital formation due to increase in investment, domestic savings and FDI flows. Furthermore, it shows the increase in capital productivity and capital-labour ratio due to the substitution of labour with capital. According to the paper, labour productivity also increased due to expansion of small-scale enterprises in rural areas and decrease in barriers of labour migration between urban and rural areas. Therefore, China has faced an increasing trend in terms of total productivity in this period. (Fang & Dewen ) explained about the predictions regarding the effects of demographic transitions. They had mentioned about the decrease in young age dependency ratio and increase in working population and its benefits on the growth of China. But on the other hand, the paper gives predictions which stated the change of demographic dividend into demographic debt. They predicted that due to the decrease in fertility rates due to the one child policy, the working population will shrink, whereas, the old age dependency ratio will keep increasing. Due to this the government’s expenditure on the well-being of the aged population will increase and the savings rate per household will also see a rise. These predictions by Fang and Dewen were proved to hold true as China went through the demographic transition. One paper focuses on the how the saving- investment balance will evolve in the decades ahead (Kuijs, 2006). China sees high household savings compared to other OECD countries. That being said, the primary source of the high economy-wide saving is owing to strangely high enterprise and government saving. The saving and investment in China is higher than expected, even post adjusting economic structural differences. As of 2006, analysts observed that saving and investment both would only mildly deteriorate in China in the following 2 decades, on the basis of projected structural developments including urbanization and demographics. On the other hand, the saving-investment balance of several policy adjustments could be large. Once the policies are identified, it is suggested that rebalancing could reduce current and saving account surpluses, even though it is not likely that saving surpluses will turn into a deficit anytime soon. The paper explores how China’s saving, investment, and the saving-investment balance can evolve in the decades ahead. Household saving in China is relatively high, compared to OECD countries. The paper proves that households in China contribute greatly to national saving. The household saving rate, as a percentage of household disposable income, rose steadily from about 5 % before 1978 to over 30 % in the mid-1990s. Thereafter, it declined gently to around 25 percent in 2000, at which it broadly remained since. As a share of GDP, household saving is estimated to have been around 16% in recent years. This is significantly more than in OECD countries, but less than in India, the other large developing country currently undergoing a rapid integration in the world economy, but with much lower overall saving and investment and a very different sector composition of saving. 5 As mentioned above, the literature has primary focus on households. While this misses’ multiple factors driving saving, the paper investigates possible reasons for China’s relatively high household saving rate, compared to OECD countries. Those that are commonly seen as having had a major role in China are demographics; high economic growth; (lack of) government policy and spending on health, education, and social safety; and (lack of) financial sector development. Relatively high household saving in China also appears to be a result of the “withdrawal of the government” in many spheres during the transition. International evidence suggests such effects on precautionary saving occur. Chou, Liu, and Hammitt (2003) found that introduction of a National Health Insurance in Taiwan reduced household saving by an average of 9-14%. For China, surveys appear to confirm that household saving is motivated by precautionary motives. (Zhi, 2015) uses regression results to analyse the determinants of China's Household Savings using variables like Long Term Per Capita Growth, Demographic Structure, Inflation, Housing prices and pension based on sample data from 1978-2012. The study found a positive relation between household saving and long. Term Per Capita Growth (15 years period) as Income growth was steady, people had more money to save. Demographic Structure also showed a positive relation, a one percent point increase in Dependency can lead to 4.86 percentage point increase in Household Saving. The enactment of One Child Policy will cause an increase in Old Age Dependency and hence increase in Household Savings. With fewer children, consumption will decrease and savings would rise because younger population would tend save for their own old age. Inflation would affect saving behaviour but it is frail in explaining. Housing prices seemed to have a positive relation. As housing prices increase people save to buy more houses, decrease their consumption to some level but limited data could not statistically prove the same. After adding Pension data, dependency ratio (demographic structure) will not be significant. As pension distribution grew, people to increase their consumption more now and save less for future. Hence, keeping reliable with Modigliani method, Longs Term Income Growth and Demographic are two main determinants for household saving. (Chamon, Lui , & Prasad, December 2010) mentioned the reason behind the increase in household savings in their paper on Income Uncertainty and Household Savings in China. According to them, the main reason behind the rising savings in the younger households is the uncertain transitory shocks to the levels of income. The pension reforms post the demographic transition reduced the pension replacement income as the old age dependency increased on the declining working population. These made the older households save more as they approached retirement. (Nofri, 2015) observed that labour productivity in China has improved on YoY (year on year) basis in December 2017 by 6.85%, compared with the growth of 6.49% in the previous year. It was observed that by 1970, by primarily exploiting labour cost advantages, China has risen to middle income status. But these advantages vanish once the pool of surplus labour is exhausted and wages start to accelerate. The trend of rural migration to urban centres is creating a steady and growing supply of low-cost labour, thus the numbers are falling downward, rapidly. The wages are rising faster than the GDP. 6 CHAPTER: 3 METHODOLOGY The data used in this paper is taken up from World Bank open data, International Monetary Fund and Chinese yearbook, 2017. Table 1: Dependency Ratio and Labour Force Participation Years 1982 1987 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Old Age Dependency Ratio (%) 8.0 8.3 8.3 9.0 9.3 9.2 9.5 9.2 9.5 9.7 9.9 10.2 9.9 10.1 10.4 10.7 10.7 10.7 11.0 11.1 11.3 11.6 11.9 12.3 12.7 13.1 13.7 14.3 15.0 Young age Dependency ratios (%) 54.6 43.5 41.5 41.8 41.7 40.7 40.5 39.6 39.3 38.5 38.0 37.5 32.6 32.0 31.9 31.4 30.3 28.1 27.3 26.8 26.0 25.3 22.3 22.1 22.2 22.2 22.5 22.6 22.9 Labour Force Participation (%) 79.13 79.05 78.98 78.92 78.83 78.69 78.50 78.26 77.96 77.62 77.22 76.49 75.69 74.85 74.07 73.38 72.79 72.30 71.88 71.45 70.97 70.74 70.53 70.30 70,04 69.74 69.37 Source: China’s Statistical Yearbook 2017, worldbank.org 7 The above table shows the trend between the old age dependencies, young age dependencies and Labour force participation due to the introduction of the ‘One Child Policy’ in China. Post the implementation of the policy, the Old age dependency ratio started increasing vis-à-vis the young age dependency ratio, which was on a decline. Due to the decline of the working population as a consequence of the said policy, the participation of efficient labour in the country can be seen to have been decreased. Since 2011, the industrial and agricultural sector faced a severe shortage in the labour force. After this phenomenon, the ‘One Child Policy’ was abolished (in 2015) to avoid the risk of further weakening in the labour force participation in China. As the Dependency ratio was on a rise, the households started saving for the future precautionary motive. This led to the increase in saving behaviour among the population. Figure 1: Dependency Ratios 60 50 40 30 OADR YADR 20 10 0 8 Table 2: Savings, Capital Investment, Inventories, GFCF Years 1982 1987 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Household Savings in % of Disposable Income 33.98 31.72 33.86 29.61 31.04 31.77 32.23 29.69 28.25 28.01 27.21 30.22 30.57 31.51 34.35 35.80 37.32 37.84 38.99 38.10 38.11 38.46 37.99 37.07 _ Savings, Capital In billion Investment, dollars In billion dollars Changes in Inventories In billion dollars Gross fixed Capital Formation In Billion dollars 72.83 105.5 138.23 153.74 178.44 190.83 241.96 296.68 343.94 377.20 402.94 409.29 441.64 512.29 585.75 730.83 921.66 1094.17 1389.76 1845.92 2387.25 2611.35 3141.66 3746.07 4259.02 4700.96 5205.18 5354.52 5175.54 7.67 18.46 36.69 36.54 37.24 27.53 31.66 47.72 50.95 43.46 19.87 17.20 12.06 27.96 16.10 22.62 45.31 21.03 32.60 91.94 147.37 78.80 159.90 211.34 168.54 179.92 206.14 181.97 166.36 59.48 85.68 88.64 100.95 132.82 169.22 199.42 243.78 280.48 305.96 347.27 365.31 405.00 459.87 529.14 651.98 793.42 925.15 1094.02 1381.08 1842.03 2294.33 2745.12 3400.00 3875.00 4373.21 4721.00 4841.09 4787.00 67.16 104.14 125.34 137.5 170.07 196.76 231.08 291.5 331.44 349.42 357.15 382.51 417.06 487.84 545.24 674.6 838.74 946.19 1126.54 142.85 1989.48 2373.13 2904.64 3611.04 4043.53 4552.65 4927.52 5023.46 4962.41 Source: worldbank.org 9 The trends above firstly show the perpetual increase of the savings of the country as a whole from USD 72 billion just 3 years after the implementation the Policy to about a whopping USD 5175 billion as of 2016. With the increase in savings, there was a subsequent increase in fixed assess investment. There was an expected increase in the rate of return on capital. This rate of return was also consistent due to technological improvements. This further increased investment which boosted the formation of capital in the country, showing a USD 4787 billion GFCF figure as of 2016. This figure comprised structure, building machinery and equipment. Another major reason for the steady increases was the positive externalities. The contribution to capital formation was also made by FDI and international trade. A sharp increase in internal competition led to an increase in exports, which boosted inventories. Table 3: Expenditure on Research and Development Years 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 R&D expenditure % of GDP 0.56 0.64 0.65 0.75 0.9 0.94 1.06 1.12 1.21 1.31 1.37 1.37 1.44 1.66 1.71 1.78 1.91 1.99 2.02 2.07 Source: China’s Statistical Yearbook, 2017 The research and development consist business enterprise, higher education, government and private non-profit sectors. The Government expenditure on research and development was 188.20 USD million in 2012 which further increased to 269.56 USD million in 2016. As a % of GDP, its share rose to 2.07% in 2015 from a mere 0.56% in 1996. The number of R&D projects rose from 79343 in 2012 to 100925 in 2016. 10 CHAPTER 4 PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS Table 4: Total Factor Productivity Years 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Factor Productivity (Index 2011=1, not seasonally adjusted) 0.707 0.716 0.679 0.683 0.691 0.709 0.752 0.784 0.821 0.847 0.898 0.954 0.952 0.977 0.993 1.000 1.014 1.029 Source: Chinese yearbook 2017 Initially, the labour force participation was low. There was a vacancy of efficient labour in the industrial sector, which caused a migration and subsequent efficient allocation of labour from the rural to urban sectors. This led to an increase in the labour per output. Capital productivity saw a decline as investments were high and inefficient, and improperly allocated. Investment is SOEs were negligible. Eventually, surplus labour nearly vanished. Capital productivity increased and replaced labour. Proper distribution of capital was seen, and there was also availability of capital to the SOEs. Thus, labour replaced capital. The total factor productivity increased because of a compensation of lack of labour by capital, as also improvement in technology and education. 11 Figure 2: Trends in Total Factor Productivity TFP 1,2 1 0,8 0,6 TFP 0,4 0,2 0 12 CHAPTER: 5 CONCLUSION: For 35 years, the “One Child Policy” has been affecting China. It has affected the nation socially, politically and economically. It has affected the country in more ways than one. It has taken away the Chinese people’s basic right. The Chinese government has taken away their choice. Due to all these concerns faced by them, reforms were made to abolish the policy in the year 2015. However, the policy saw a major impact on the Chinese economy during its time period. In the initial years of the policy implementation, the old age dependency ratio was increasing, with no addition to the labour force of the country. The lack in efficient labour force found in the industrial sector saw a rise in the mobility levels of labourers from the agricultural sector to the industrial sector. This rise in the formal sector workings led to an increase in the labour productivity in the country. During these years of the policy, the capital productivity levels slowed down as a consequence of excess levels of investment and insufficient capital allocation among the sectors especially the SOEs. Since 2011, the Chinese economy saw various negative effects of the policy, such as the decrease in the labour productivity. On the contrary, the capital productivity increased due to increase in the capital formation and proper distribution of capital resources in the various sectors, especially the small-scale industries. Similarly, the technological advancements in the country raised the productivity levels. This was the main reason that allowed China to maintain its increasing trends of high productivity in spite of the drop-in labour productivity levels. RECOMMENDATIONS: 1. The working age of the population should be increased, i.e. the retirement age should be decreased. 2. Increase the levels of investment in public infrastructure, such as, public healthcare, social security, education and employment. 3. There should be an increase in the Research and Developments in the country. 4. The government should be more favourable to domestic private enterprises. 5. Due to lack of surplus labour, the labour costs i.e. wages have increased. For this reason, they should encourage import of cheap labour. 13 FUTURE SCOPE: If the policy were to be continued, There would have been a further increase the old age dependency which would then burden the limited working population therefore, increasing the precautionary savings among the households. This would have then reduced the consumption levels and thus the decrease the aggregate demand of the country, increasing the inflationary pressures. However, with the withdrawal of the policy, The above-mentioned consequences aren’t seen. The country might regain its initial levels of surplus labour and have a more efficient labour productivity in the coming years. Higher levels of investment usually lead to lower marginal productivity of capital investment but this was not the case in China. They managed to keep their capital productivity by channelizing their capital in an efficient manner. They have invested substantial amounts in human capital which has been creating efficient units of labour further increasing the profitability of investment. This is how China kept an overall increasing trend in the Total Factor Productivity. 14 REFRENCES Avuk, A., Benkova , K., & Vojtka , M. (May 2012). Economic Impact of One Child Policy In People's Republic of China. Chamon, M., Lui , K., & Prasad, E. (December 2010). Income Uncertainity and Household Savings in China. IMF Working Paper . Fang, C., & Dewen , W. Demographic Transition and Economic Growth in China . Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Jianguo, Y. T., & Zhang, X. (2017). China's Investment and Rate of Return on Capital. Journal of Asian Economics . Knight, J., & Ding , S. (July 2009). Why does China invest so much? Department of Economics, Oxford University. Kuijs, L. (2006). How will China's Savings-Investment Balance Evolve? World Bank China Research Paper . Nofri, E. M. (2015, July 13th). Alberto Forchieli blog. Retrieved from http://www.albertoforchielli.com Ozyurt, S. Total Factor p. Ozyurt, S. (2005). Total Factor Productivity growth in the chinese Industry. Stratford, K., & Cowling, A. Chinese Household Income Consumption and Savings. Zhi, N. (2015). The Determinants of Chinese Household Savings During 1978-2012. Honor Thesis. 15