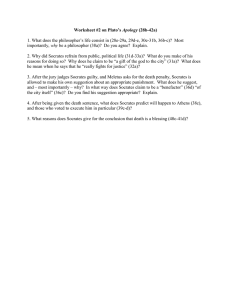

Socrates: Philosophical Life Socrates (469-399) One of the most interesting and influential thinker in the 5th Century BCE was Socrates, whose dedication to careful reasoning transformed the entire enterprise. Since he sought genuine knowledge rather than mere victory over an opponent, Socrates employed the same logical tricks developed by the Sophists to a new purpose, the pursuit of truth. Thus, his willingness to call everything into question and his determination to accept nothing less than an adequate account of the nature of things make him the first clear exponent of critical philosophy. Socrates was a stone cutter by trade, even though there is little evidence that he did much to make a living. However, he did have enough money to own a suit of armor when he was in the Athenian military. Socrates' mother was a midwife. He was married and had three sons. Throughout his life he claimed to hear voices which he interpreted as signs from the gods. It appears that Socrates spent much of his adult life in the marketplace conversing about ethical issues. He had a penchant for exposing ignorance, hypocrisy, and conceit among his fellow Athenians, particularly in regard to moral questions. In all probability, he was disliked by most of them. However, Socrates did have a loyal following. He was very influential in the lives of Plato, Euclid, Alcibiades, and many others. Socrates is admired by many philosophers for his willingness to explore an argument wherever it would lead as well as having the moral courage to follow its conclusion. Although he was well known during his own time for his conversational skills and public teaching, Socrates wrote nothing, so we are dependent upon his students (especially Xenophon and Plato) for any detailed knowledge of his methods and results. Euthyphro: What is Moral Duty (Piety)? Socrates engaged in a sharply critical conversation with an over-confident young man. Finding Euthyphro perfectly certain of his own ethical rightness even in the morally ambiguous situation of prosecuting his own father in court, Socrates asks him to define what "piety" (moral duty) really is. The demand here is for something more than merely a list of which actions are, in fact, pious; instead, Euthyphro is supposed to provide a general definition that captures the very essence of what piety is. But every answer he offers is subjected to the full force of Socrates's critical thinking, until nothing certain remains. Specifically, Socrates systematically refutes Euthyphro's suggestion that what makes right actions right is that the gods love (or approve of) them. First, there is the 1 obvious problem that, since questions of right and wrong often generate disputes, the gods are likely to disagree among themselves about moral matters no less often than we do, making some actions both right and wrong. Socrates lets Euthypro off the hook on this one by agreeing—only for purposes of continuing the discussion—that the gods may be supposed to agree perfectly with each other. More significantly, Socrates generates a formal dilemma from a (deceptively) simple question: "Is the pious act loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" (Euthyphro 10 a) Neither alternative can do the work for which Euthyphro intends his definition of piety. If right actions are pious only because the gods love them, then moral rightness is entirely arbitrary, depending only on the whims of the gods. If, on the other hand, the gods love right actions only because they are already right, then there must be some non-divine source of values, which we might come to know independently of their love. In fact, this dilemma proposes a significant difficulty at the heart of any effort to define morality by reference to an external authority. (Consider, for example, parallel questions with a similar structure: "Do my parents approve of this action because it is right, or is it right because my parents approve of it?" or "Does the College forbid this activity because it is wrong, or is it wrong because the College forbids it?") On the second alternative in each case, actions become right (or wrong) solely because of the authority's approval (or disapproval); its choice, then, has no rational foundation, and it is impossible to attribute laudable moral wisdom to the authority itself. So this horn is clearly unacceptable. But on the first alternative, the authority approves (or disapproves) of certain actions because they are already right (or wrong) independently of it, and whatever rational standard it employs as a criterion for making this decision must be accessible to us as well as to it. Hence, we are in principle capable of distinguishing right from wrong on our own. Thus, an application of careful techniques of reasoning results in genuine (if negative) progress in the resolution of a philosophical issue. Socrates's method of insistent questioning at least helps us to eliminate one bad answer to a serious question. At most, it points us toward a significant degree of intellectual independence. The character of Euthyphro, however, seems unaffected by the entire process, leaving the scene at the end of the dialogue no less self-confident than he had been at its outset. The use of Socratic methods, even when they clearly result in a rational victory, may not produce genuine conviction in those to whom they are applied. Apology: The Examined Life 2 Because of his political associations with an earlier regime, the Athenian democracy put Socrates on trial, charging him with undermining state religion and corrupting young people. The speech he offered in his own defense, as reported in Plato's Apology, provides us with many reminders of the central features of the Socratic approach to philosophy and its relation to practical life. a. Ironic Modesty: Explaining his mission as a philosopher, Socrates reports an oracular message telling him that "No one is wiser than you." (Apology 21a) He then proceeds through a series of ironic descriptions of his efforts to disprove the oracle by conversing with notable Athenians who must surely be wiser. In each case, however, Socrates concludes that he has a kind of wisdom that each of them lacks: namely, an open awareness of his own ignorance. b. Devotion to Truth: Even after he has been convicted by the jury, Socrates declines to abandon his pursuit of the truth in all matters. Refusing to accept exile from Athens or a commitment to silence as his penalty, he maintains that public discussion of the great issues of life and virtue is a necessary part of any valuable human life. "The unexamined life is not worth living." (Apology 38a) Socrates would rather die than give up philosophy, and the jury seems happy to grant him that wish. c. Dispassionate Reason: Even when the jury has sentenced him to death, Socrates calmly delivers his final public words, a speculation about what the future holds. Disclaiming any certainty about the fate of a human being after death, he nevertheless expresses a continued confidence in the power of reason, which he has exhibited (while the jury has not). Who really wins will remain unclear. Plato's dramatic picture of a man willing to face death rather than abandoning his commitment to philosophical inquiry offers up Socrates as a model for all future philosophers. Perhaps few of us are presented with the same stark choice between philosophy and death, but all of us are daily faced with opportunities to decide between convenient conventionality and our devotion to truth and reason. How we choose determines whether we, like Socrates, deserve to call our lives philosophical. 3 Crito: The Individual and the State Plato's description of Socrates's final days continued in the Crito. Now in prison awaiting execution, Socrates displays the same spirit of calm reflection about serious matters that had characterized his life in freedom. Even the patent injustice of his fate at the hands of the Athenian jury produces in Socrates no bitterness or anger. Friends arrive at the jail with a foolproof plan for his escape from Athens to a life of voluntary exile, but Socrates calmly engages them in a rational debate about the moral value of such an action. Of course Crito and the others know their teacher well, and they come prepared to argue the merits of their plan. Escaping now would permit Socrates to fulfill his personal obligations in life. Moreover, if he does not follow the plan, many people will suppose that his friends did not care enough for him to arrange his escape. Therefore, in order to honor his commitments and preserve the reputation of his friends, Socrates ought to escape from jail. But Socrates dismisses these considerations as irrelevant to a decision about what action is truly right. What other people will say clearly doesn't matter. As he had argued in the Apology, the only opinion that counts is not that of the majority of people generally, but rather that of the one individual who truly knows. The truth alone deserves to be the basis for decisions about human action, so the only proper approach is to engage in the sort of careful moral reasoning by means of which one may hope to reveal it. Socrates's argument proceeds from the statement of a perfectly general moral principle to its application in his particular case: One ought never to do wrong (even in response to the evil committed by another). But it is always wrong to disobey the state. Hence, one ought never to disobey the state. And since avoiding the sentence of death handed down by the Athenian jury would be an action in disobedience of the state, it follows Socrates ought not to escape. The argument is a valid one, so we are committed to accepting its conclusion if we believe that its premises are true. The general commitment to act rightly is fundamental to a moral life, and it does seem clear that Socrates's escape would be a case of disobedience. But what about the second premise, the claim that it is always wrong for an individual to disobey the state? Surely that deserves further examination. In fact, Socrates pictures the laws of Athens proposing two independent lines of argument in favor of this claim: First, the state is to us as a parent is to a child, and since it is always wrong for a child to disobey a parent, it follows that it is always wrong to disobey the state. (Crito 50e) Here we might raise serious doubts about the legitimacy of the analogy between our parents and the state. Obedience to our parents, 4 after all, is a temporary obligation that we eventually outgrow by learning to make decisions for ourselves, while Socrates means to argue that obeying the state is a requirement right up until we die. Here it might be useful to apply the same healthy disrespect for moral authority that Socrates himself expressed in the Euthyphro. The second argument is that it is always wrong to break an agreement, and since continuing to live voluntarily in a state constitutes an agreement to obey it, it is wrong to disobey that state. (Crito 52e) This may be a better argument; only the second premise seems open to question. Explicit agreements to obey some authority are common enough—in a matriculation pledge or a contract of employment, for example—but most of us have not entered into any such agreement with our government. Even if we suppose, as the laws suggest, that the agreement is an implicit one to which we are committed by our decision to remain within their borders, it is not always obvious that our choice of where to live is entirely subject to our individual voluntary control. Nevertheless, these considerations are serious ones. Socrates himself was entirely convinced that the arguments hold, so he concluded that it would be wrong for him to escape from prison. As always, of course, his actions conformed to the outcome of his reasoning. Socrates chose to honor his commitment to truth and morality even though it cost him his life. The Method and Doctrine of Socrates – Philosophy of Education Socrates would best be described as an “educator” not a “philosopher,” nor a “teacher,” because he saw his functions as being to rouse, persuade and rebuke (Plato, Apology). Hence, in examining his life’s work it is proper to ask, not What was his philosophy? But What was his theory?, and What was his practice of education? It is true that he was brought to his theory of education by the study of previous philosophies, and that his practice led to the Platonic revival. Socrates' theory of education had for its basis a profound and consistent skepticism; that is to say, he not only rejected the conflicting theories of the physicists, of whom “some conceived existence as a unity, others as a plurality; some affirmed perpetual motion, others perpetual rest; some declared becoming and perishing to be universal, others altogether denied such things,” but also condemned, as a futile attempt to transcend the limitations of human intelligence their, "pursuit of knowledge for its own sake.” Unconsciously or more probably consciously, Socrates rested his skepticism upon the Protagorean doctrine that humans are the measure of their own sensations and feelings; whence he inferred, not only that knowledge such as the philosophers had sought, certain knowledge of nature and its laws, was unattainable, but also that neither he nor any other 5 person had authority to overbear the opinions of another, or power to convey instruction to one who had it not. Accordingly, whereas Protagoras and others, abandoning physical speculation and coming forward as teachers of culture, claimed for themselves in this new field power to instruct and authority to dogmatize, Socrates, unable to reconcile himself to this inconsistency, proceeded with the investigation of principles until he found a resting place in the distinction between good and evil. While all opinions were equally true, of these opinions which were capable of being translated into act, he conceived, were as working hypotheses more serviceable than others. It was here that the function of such a one as himself began. Though he had neither the right nor the power to force his opinions upon another, he might by a systematic interrogatory lead another to substitute a better opinion for a worse, just as a physician by appropriate remedies may enable his patient to substitute a healthy sense of taste for a morbid one. To administer such an interrogatory and thus to be the physician of souls was, Socrates thought, his divinely appointed duty; and, when he described himself as a “talker “or” converser,” he not only negatively distinguished himself from those who, whether philosophers or sophists, called themselves “teachers," but also positively indicated the method of question and answer which he consistently preferred and habitually practiced. That it was in this way that Socrates was brought to regard “dialectic,” “question and answer,” as the only admissible method of education is no matter of mere conjecture. In the review of theories of knowledge which has come down to us in Plato’s Theaetetus mention is made of certain “incomplete Protagoreans,” who held that, while all opinions are equally true, one opinion is better than another, and that the “wise man” is one who by his arguments causes good opinions to take the place of bad ones, thus reforming the soul of the individual or the laws of a state by a process similar to that of the physician or the farmer; and these “incomplete Protagoreans” are identified with Socrates and the Socratics by their insistence upon the characteristically Socratic distinction between disputation and dialectic, as well as by other familiar traits of Socratic converse. In fact, this passage becomes intelligible and significant if it is supposed to refer to the historical Socrates; and by teaching us to regard him as an “incomplete Protagorean” it supplies the link which connects his philosophical skepticism with his dialectical theory of education. It is no doubt possible that Socrates was unaware of the closeness of his relationship to Protagoras; but the fact, once stated, hardly admits of question. In the application of the “dialectical“ method two processes are distinguishable: the destructive process, by which the worse opinion was eradicated, and the constructive 6 process, by which the better opinion was induced. It was not mere “ignorance “ with which Socrates had to contend, but “ignorance mistaking itself for knowledge” or “false conceit of wisdom,“ a more stubborn and a more formidable foe, who safe so long as he remained in his entrenchments, must be drawn from them, circumvented, and surprised. Accordingly, taking his departure from some apparently remote principle or proposition to which, the respondent yielded a ready assent, Socrates would draw from it an unexpected but undeniable consequence which was plainly inconsistent with the opinion impugned. In this way he brought his interlocutor to pass judgment upon himself, and reduced him to a state of doubt or perplexity. “Before I ever met you,” says Meno in the dialogue which Plato called by his name, I was told that you spent your time in doubting and leading others to doubt; and it is a fact that your witcheries and spells have brought me to that condition; you are like the torpedo: as it benumbs any one who approaches and touches it, so do you. For myself, my soul and my tongue are benumbed, so that I have no answer to give you.” Even if as often happened, the respondent baffled and disgusted by the destructive process, at this point withdrew from the inquiry, he had, in Socrates' judgment, gained something; for, whereas formerly, being ignorant, he had supposed himself to have knowledge, now, being ignorant, he was in some sort conscious of his ignorance, and accordingly would be for the future more circumspect in action. If, however, having been thus convinced of ignorance, the respondent did not shrink from a new effort, Socrates was ready to aid him by further questions of a suggestive sort. Consistent thinking with a view to consistent action being the end of the inquiry, Socrates would direct the respondent’s attention to instances analogous to that in hand, and so lead him to frame for himself a generalization from which the passions and the prejudices of the moment were, as far as might be, excluded. In this constructive process, though the element of surprise was no longer necessary, the interrogative form was studiously preserved, because it secured at each step the conscious and responsible assent of the learner. Of the two processes of the dialectical method, the destructive process attracted the more attention, both in consequence of its novelty and because many of those who willingly or unwillingly submitted to it stopped short at the stage of “perplexity.” But to Socrates and his intimates the constructive process was the proper and necessary sequel. It is true that in the dialogues of Plato the destructive process is not always, or even often, followed by construction, and that in the Memorabilia of Xenophon construction is not always, or even often, preceded by the destructive process. There is, however, in this nothing surprising. On the one hand, Xenophon, having for his principal purpose the defense of 7 his master against vulgar calumny, seeks to show by effective examples the excellence of his positive teaching, and accordingly is not careful to distinguish, still less to emphasize, the negative procedure. On the other hand, Plato, his aim being not so much ‘to preserve Socrates' positive teaching as rather by written words to stimulate the reader to selfscrutiny, just as the spoken words of the master had stimulated the hearer, is compelled by the very nature of his task to keep the constructive element in the background, and, where Socrates would have drawn an unmistakable conclusion, to confine himself to hints. For example, when we compare Xenophon’s Memorabilia, with Plato’s Euthypliro, we note that, while in the former the interlocutor is led by a few suggestive questions to define “piety” as “the knowledge of those laws which are concerned with the gods,” in the latter, though on a further scrutiny it appears that “piety “is’ “that part of justice which is concerned with the service of the gods,” the conversation is ostensibly inconclusive. In short, Xenophon, a mere reporter of Socrates' conversations, gives the results’, but troubles himself little about the steps which led to them; Plato, who in early manhood was an educator of the Socratic type, withholds the results that he may secure the advantages of the stimulus. What, then, were the positive conclusions to which Socrates carried his hearers, and how were those positive conclusions obtained? Turning to Xenophon for an answer to Induction these questions, we note (1) that the recorded conversations are concerned with practical action, political, definition, moral, or artistic; (2) that in general there is a process from the known to the unknown through a generalization, expressed or implied; (3) that the generalizations are sometimes rules of conduct, justified by examination of known instances, sometimes definitions similarly established. Thus in Memorabilia, Socrates argues from the known instances of horses and dogs that, the best natures stand most in need of training, and then applies the generalization to the instance and discussion of men; and he leads his interlocutor to a definition of “the good citizen,” and then uses it to decide between two citizens for whom respectively superiority is claimed. Now in the former of these cases the process which Aristotle would describe as “example “and a modern might regard as “induction” of an uncritical sort sufficiently explains itself. The conclusion is a provisional assurance that in the particular matter in hand a certain course of action is, or is not, to be adopted. But it is necessary to say a word of explanation about the latter case, in which, the generalization being a definition, that is to say, a declaration that to a given term the interlocutor attaches in general, a specified meaning, the conclusion is a provisional assurance that the interlocutor may, or may not, without falling into inconsistency, apply 8 the term in question to a certain person or act. Moral error, Socrates conceived, is largely due to the misapplication of general terms, which, once affixed to a person or to an act, possibly in a moment of passion or prejudice, too often stand in the way of sober and careful reflection. It was in order to exclude error of this sort that Socrates insisted upon its basis. By requiring a definition and the reference to it of the act or person in question, he sought to secure in the individual at any rate consistency of thought, and in so far, consistency of action. Accordingly he spent his life in seeking and helping others to seek “the what” or the definition, of the various words by which the moral quality to actions is described, valuing the results thus obtained not as contributions to knowledge, but as means to right action in the multifarious relations of life. While Socrates sought neither knowledge, which in the strict sense of the word he held to be unattainable, nor yet, except as a means to right action, true opinion, the results of observation accumulated until they formed, not perhaps a system of ethics, but at any rate a body of ethical doctrine. Himself blessed with a will so powerful that it moved almost without friction, he fell into the error of ignoring its operations, and was thus led to regard knowledge as the sole condition of well doing. Where there is knowledge, that is to say, practical wisdom, the only knowledge which he recognized, right action, he conceived, follows of itself; for no one knowingly prefers what is evil; and, if there are cases in which men seem to act against knowledge, the inference to be drawn is, not that knowledge and wrongdoing are compatible, but that in the cases in question the supposed knowledge was after all ignorance. Virtue, then, is knowledge, knowledge at once of end and of means, irresistibly realizing itself in act. Whence it follows that the several virtues which are commonly distinguished are essentially one. Piety, justice, courage and temperance are the names which wisdom bears in different spheres of action: to be pious is to know what is due to the gods; to be just is to know what is due to men; to be courageous is to know what is to be feared and what is not; to be temperate is to know how to use what is good and avoid what is evil. Further, in as much as virtue is knowledge, it can be acquired by education and training, though it is certain that one's soul has by nature a greater aptitude than another for such acquisition. But, if virtue is knowledge, what has this knowledge for its object? To this question Socrates replies, Its object is the Good. What, then, is the Good? It is the useful, the advantageous. Utility, the immediate utility of the individual, thus Theory becomes the measure of conduct and the foundation the Good of all moral rule and legal enactment. Accordingly, each precept of which Socrates delivers himself is recommended that 9 obedience to it will promote the comfort, the advancement, the well being of the individual; and Prodicus' apologue of the Choice of Heracles, with its commonplace offers of worldly reward, is accepted as an adequate statement of the motives of virtuous action. Of the graver difficulties of ethical theory Socrates has no conception, having, as it would seem, so perfectly absorbed, the lessons of what Plato calls political virtue, that morality has become with him a second nature, and the scrutiny of its credentials from an external standpoint has ceased to be possible. His theory is indeed so little systematic that, whereas, as has been seen, virtue or wisdom has the Good for its object, he sometimes identifies the Good, with virtue or wisdom, thus falling into the error which Plato perhaps with distinct reference to Socrates, ascribes to certain cultivated thinkers. In short, the ethical theory of Socrates, like the rest of his teaching, is by confession unscientific; it is the statement of the convictions of a remarkable nature, which statement emerges in the course of an appeal to the individual to study consistency in the interpretation of traditional rules of conduct. 10