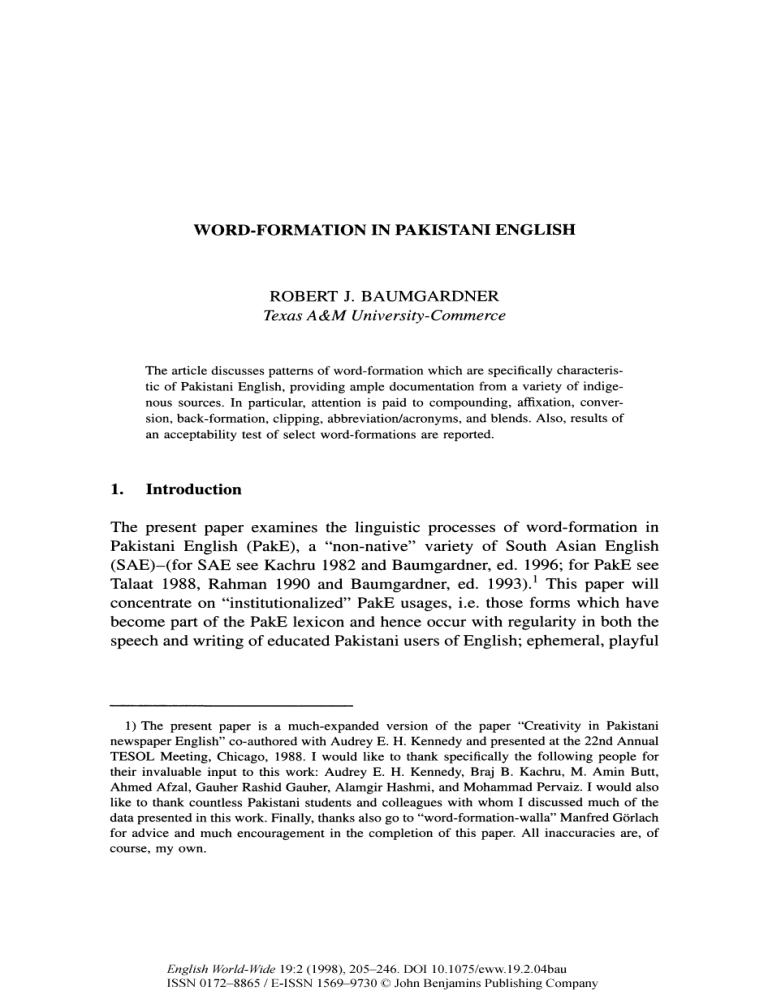

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

Texas A&M University-Commerce

The article discusses patterns of word-formation which are specifically characteristic of Pakistani English, providing ample documentation from a variety of indigenous sources. In particular, attention is paid to compounding, affixation, conversion, back-formation, clipping, abbreviation/acronyms, and blends. Also, results of

an acceptability test of select word-formations are reported.

1.

Introduction

The present paper examines the linguistic processes of word-formation in

Pakistani English (PakE), a "non-native" variety of South Asian English

(SAE)-(for SAE see Kachru 1982 and Baumgardner, ed. 1996; for PakE see

Talaat 1988, Rahman 1990 and Baumgardner, ed. 1993).1 This paper will

concentrate on "institutionalized" PakE usages, i.e. those forms which have

become part of the PakE lexicon and hence occur with regularity in both the

speech and writing of educated Pakistani users of English; ephemeral, playful

1) The present paper is a much-expanded version of the paper "Creativity in Pakistani

newspaper English" co-authored with Audrey E. H. Kennedy and presented at the 22nd Annual

TESOL Meeting, Chicago, 1988. I would like to thank specifically the following people for

their invaluable input to this work: Audrey E. H. Kennedy, Braj B. Kachru, M. Amin Butt,

Ahmed Afzal, Gauher Rashid Gauher, Alamgir Hashmi, and Mohammad Pervaiz. I would also

like to thank countless Pakistani students and colleagues with whom I discussed much of the

data presented in this work. Finally, thanks also go to "word-formation-walla" Manfred Gorlach

for advice and much encouragement in the completion of this paper. All inaccuracies are, of

course, my own.

English World-Wide 19:2 (1998), 205-246. DOI 10.1075/eww.l9.2.04bau

ISSN 0172-8865 / E-ISSN 1569-9730 © John Benjamins Publishing Company

206

ROBERT J. B A U M G A R D N E R

usages will be touched upon only peripherally.2 Because PakE is a secondlanguage, non-native variety of English and functions within a multilingual

context in Pakistan, any discussion of word-formation in this variety must

also include an analysis of processes which extend beyond the internal wordformation resources of the English language. Therefore, also included here

is a discussion of established hybrid word-formations, which have resulted

from the contact of English with Pakistani languages, principally Urdu. It is

hence hoped that the present paper will serve not only as an analysis of the

word-formation processes of the PakE lexicon but will also serve to a limited

extent as a partial record of the lexicon itself.

Data for my analysis is based upon English-language daily and weekly

newspapers published in the Pakistani cities of Islamabad (Punjab), Karachi

(Sind), Lahore (Punjab), Peshawar (North Western Frontier Province), and

Quetta (Balochistan) for a seven-year period (1986-1992).3 The data in

Section 2 will be analyzed utilizing the terminology found in the outline of

English word-formation by Bauer (1983:201-40); for clarification of specific

points, reference will also sometimes be made to other frameworks. Word-

2) No claim is made that the examples are exclusive to Pakistan; in fact, some go back to

British India and are found in word-lists of Indian English as well. For example some of the

lexemes in this paper also appear in Nihalani, Tongue and Hosali (1979), e.g. externment,

free ship, rewardee, and upgradation; the scope of that seminal work was, however, much wider

than word-formation.

3) Data in this paper is taken from the following daily, weekly, and monthly publications:

BT=(Balochistan Times, Quetta); D=(Dawn, Karachi [Dak Edition]); D/L=(Dawn, Lahore);

DE=(The Democrat, Islamabad [defunct]); DN=(Daily News, Karachi); FP=(The Frontier Post,

Peshawar); FP/L=(The Frontier Post, Lahore); FR=(Friday Review, Lahore [The Nation]);

H=(Herald, Karachi); HO=(Horizons, Lahore [The Frontier Post]; KM= (Khyber Mail,

Peshawar [defunct]); M=(The Muslim, Islamabad); MA=(Midasia, Islamabad [defunct]);

MAG=(Mag, Karachi); MC=(Men's Club, Karachi); MN=(Morning News, Karachi [defunct]);

N=(The Nation, Lahore); N/I=(The Nation, Islamabad); NL=(Newsline, Karachi); NT=(Nation

Today, Karachi); NS/K=(The News, Karachi); NS/L=(The News, Lahore); FO=(Pakistan

Observer, Islamabad); PT=(The Pakistan Times, Lahore); S=(The Star, Karachi); T=(The

Tribune, Karachi [defunct]); FT=(The Friday Times, Lahore); TR=(Tuesday Review, Lahore

[Dawn]); V=(Viewpoint, Lahore [defunct]); WE=(Weekend Magazine, Lahore [The News]);

WP=(WeekendPost, Lahore [The Frontier Post]); Y=(You, Lahore [The News]). Citations dated

1986, 1987, and through August 1988 are from newspapers purchased in Quetta; citations after

August 1988 are from newspapers purchased in Lahore. Citations of words in Appendixes 1-2

sometimes differ from in-text citations.

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

207

formation processes discussed include: compounding (2.1), affixation (2.2),

conversion (2.3), back-formation (2.4), clipping (2.5), abbreviation/acronyms

(2.6), and blends (2.7). Comprehensive lists of data (Appendixes 1 and 2)

accompany discussions of compounds (2.1) and affixation (2.2); however,

because of length considerations, I will discuss only representative data from

these lists. Forms containing Urdu in the appendixes and throughout the

paper have been glossed for readers' convenience. In Section 3 of the paper,

I report on the results of a questionnaire on the grammaticality of select

word-formations as well as discuss what light PakE can shed on wordformation in general and where it fits into the ENL:ESL:EFL distinction

(Gorlach 1989). Section 4 of the paper contains concluding remarks.

2.

Analysis

2.1. Compounding

Compound forms are words made up of two or more free elements. As

Bauer (1983: 201-2) points out, compounds are normally classified according

to the function (noun, adjective, adverb, etc.) that they perform in a sentence.

Sub-classification of each type, however, can be either structural (Bauer

1983) or semantic (Marchand 1969), while some linguists use a combination

of both (Adams 1973). In an endocentric noun compound — the prototypical

type — the first element can vary (noun, adjective, adverb, particle, etc.), but

the second element is always a noun; an adjective compound therefore is one

in which the first element again may vary, but the second is invariably an

adjective. Appendix 1 contains a select group of PakE noun (two- and threeitem), pronoun, verb and adjective compounds, both English forms as well

as hybrid English-Urdu and Urdu-English forms.

As in other varieties of English, noun compounds in PakE by far

outnumber other types of compounds. While some of the English noun

compounds in Appendix 1 may be comprehensible to speakers of other

varieties of English, many will be transparent only to native PakE users or

those familiar with the variety. Non-transparent forms may include: camel

kid, a young boy sent to the Middle East for use as jockeys in camel races,

apparently because they are light and more importantly their shrill cries of

208

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

terror during the races make the camels run faster: "19,000 camel kids

smuggled to Arab Emirates" (PO 8 Jul 92:1/1); chocolate hero, a boyishly

attractive film hero; heavy amount, a large amount of money: "After deliberations in the Cabinet meeting, he formulated a policy to return first amounts

of small depositors and then holders of heavy amounts gradually" (N 9 Sep

91:14/2); loot sale, large sale of surplus goods; Muslim shower, a hose and

nozzle which provides water in toilets in Muslim countries; shpotingball, a

game in which balls are fired from a gun at a figure target; side-hero/

heroine, a supporting actor/actress; soft-corner ('soft spot), a caique from

Urdu narm goshaa: "Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has shown a soft corner

for one of his ministers who resigned early this week from the Ministry of

Youth Affairs" (FP/L 10 Aug 91:1/2), and wheelcup, a hub-cap: "The

opposition is so suspicious towards us that they blame the government even

if they lose the wheelcups of their cars" (PT 19 Aug 91:11/4).

Two lexemes from Appendix 1 — childlifter and rickshaw-wallah —

are representative of two very productive compounding patterns in PakE. A

"lifter" is a thief: "A child lifter, Abdul Karim, made an attempt to kidnap

two minor children at Kambar Mohalla, Tando Bago" (D 28 Feb 88:5/3).

Other "lifters" include: autorickshaw lifters (FP 4 Jan 86:2/3), bicycle lifters

(N 12 Jul 88:3/7), baby lifters (PT 23 Dec 90:4/8), book lifters (N 13 Mar

92:3/3), camel lifters (FP/L 20 Sep 89:3/7), car lifters (D/L 9 Aug 90:1/4),

goat lifters (D/L 9 Aug 90:1/4), luggage lifters (D/L 13 Nov 89:4/8),

motorcycle lifters (D/L 24 Dec 90:3/8), shoe lifters (FP/L 1 Aug 92:5/4), taxi

lifters (S 20 Feb 88:2/3), vehicle lifters (D 9 Feb 88:8/7), wagon-lifters (N 21

Feb 88:3/3) and wire lifters (NS/L 13 Sep 91:3/1). It is possible that these

formations are modeled after cattle-lifter (N 23 Jan 89:3/1), which is cited

(1860) in the Oxford English Dictionary (Simpson and Weiner, eds. 1989,2:

994). The only other "lifter" compounds in BrE and AmE are bottle-cap

lifter and shop-lifter (Lehnert 1971), both semantically different from the

cattle-lifter type in which the first noun in the compound is the item being

stolen or lifted.

The OED (19:852) cites wallah (also spelled walla, wala, and walah

and also used in the feminine form wall) as Anglo-Indian and deriving from

the Hindi adjective suffix -wala meaning 'pertaining to or connected with'.

In its substantive usage, wallah is attached to nouns and indicates 'one who

does sth.'; hence, a rickshaw-wallah is one who drives a rickshaw and a

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

209

balloonwalla is one who sells balloons: "This baloonwalla has chosen an

ideal place to prepare the stuff' (DE 5 June 1990: 2/3). Wallah, like -lifter,

is found in a wide range of contexts: "The 'Censorship Walas' were just

obeying the orders of those who have decided to reform the society of 'see

no evil, hear no evil, say no evil'" (N 22 Aug 91:7/6). Other attested wallas

include: boxwalla (N 16 Jul 90:11/1); coachwallas (N Midweek 7 Aug

91:8/2); competition walla (N 16 Jul 90:11/1); donkey-cart-walla (T 6 July

1989:6/1); exam centre walla (MAG 14 Sep 89:9/1); film industry wallah

(WP 10 Apr 92:4/2); law-and-order-walla (N 27 Aug 91:7/4); pushcartwallah (D/L 25 Jun 89:4/5); soda-water-bottle-opener-wallah (MAG 2 Apr

92:21/5); and walkie-talkie wallah (N 11 Aug 89:6/5). Wallah is also very

productive in Urdu, and Urdu wallah formations are often used in PakE; a

gawala is one who tends cows (gao) and a paniwala is one who sells water

(pani): "The paniwalla is the preferred source of delivering the booti

[answers] to the candidates" (N 1 Sept 91:1/4).

Within compounds Bauer (1983:203) further distinguishes the subcategory

"appositional compound". In one productive type of appositional compound in

BrE and AmE "the first element marks the sex of the person" (ibid.), for example

boy-friend, manservant or woman doctor. In PakE the last pattern is very

common, except that the lexeme "lady" is used in place of "woman": "According

to details a police party raided the notorious narcotic den in Mohallah Bakhri and

arrested alleged drug traffickers, Sakina and her daughter, Aasia, former lady

teachers and lady telephone operators" (MN 13 Jan 91:3/8). A Pakistan

Times headline in December of 1988 read "Lady Drug Trafficker Held in

City" (PT 14 Dec 88:10/7). Other instances include: lady ad-hoc lecturers

(PT 25 May 89:5/7); lady complainant (M 24 Apr 91:5/6); lady councillor

(NS/L 4 Aug 91:2/4); lady doctor (PT 3 Jul 91:5/2); lady entrepreneurs (PT

4 Sep 88:10/7); lady medical officers (M 5 Jun 91:9/6); lady newscaster

(MAG 28 Nov 91:5/3); lady passers-by (FP/L 13 Aug 91:3/5); lady police

(FP/L 29 Jul 91:5/2); lady reporter (PT 28 Jun 91:1/3); lady telephone

operator (D/L 16 Nov 90:6/1); and ex-lady MPA [Member of the Punjab

Assembly] (DE 8 Aug 90:3/6). Two fixed "lady" compounds in PakE are

lady wife and house lady. "Lady wives" are wives of military personnel and

a "house lady" is a housewife: "An attempt to rob a family was foiled here

the other day due to the presence of mind of a house lady and the culprits

were overpowered and handed over to the police" (N 25 Oct 87:3/6).

210

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

Bauer (1983:204) likewise includes in appositional compounds formations like jazz-rock. In PakE compounds of this type include tractor-trolley

("The two years old son of a fruit vendor was crushed under the wheels of

a tractor-trolley near Shahdara on Monday" [N 6 Feb 92:2/5]) and the group

coat-trousers, knicker-shirt and pant-shirt. The latter three compounds are

Western dress terms fashioned after the Urdu word shalwar-khamis, the

Pakistani national dress: "The gun-slinging young men wearing pant-shirts

arrived at the Clinic" (D 18 Feb 88:8/5). Suited-booted is a PakE (and Urdu)

appositional adjective compound: "Nusrat Ali Shah, one of the "suitedbooted" (as people in three-piece suits are called in Urdu) members of the

former assembly, was less keen on talking politics" (M 20 Sep 89:3/4). A

final type of PakE appositional compound is bed sheet (Nihalani, Tongue and

Hosali 1979), where one of the elements in the compound is semantically

redundant (in this case bed): "As a result patients were lying on beds

exposed to severe risk of getting some infectious diseases because of the

dirty bed sheets" (FP/L 8 Jun 92:2/3). Hybrid appositional compounds, in

which the second noun is either an English or Urdu translation of the first,

can also be pleonastic, e.g. challan ticket, (challan 'ticket'), and fruit mandi

market, (mandi 'market'): "They will bring me a number which I shall bring

back to him after which he will issue me a challan ticket" (N 12 Dec 91:7/2).

As can be seen from Appendix 1, the majority of PakE noun compounds are of the Noun+Noun and Adjective+Noun type. Other types include

rank reduction (Kachru 1983:136), which can be regarded as postmodifications with of derived from two-item compounds, e.g. PakE cattle head, 'head

of cattle', baggage piece, 'piece of baggage', matchbox, 'box of matches'

and perfume bottle, 'bottle of perfume'. "The district police launched a

vigorous drive against cattle-lifting and recovered stolen cattle heads worth

about Rs. 2.5 lakh and arrested 24 members of the gangs" (PT 24 Oct

86:9/6). Goodself is a PakE compound pronoun and serves as a polite form:

"THE PUNJAB HEALTH DEPARTMENT requests the pleasure of the

company of your goodself alongwith your young children at the nearest

vaccination centres for immunization against fatal diseases..." (M 15 May

86:1/7). Some common PakE three-item compounds and collocations include

fair price shop, government price-controlled shops in which items of daily use

[staples] can be bought, fixed-spot hawkers, and chaddar-laying ceremony, a

ceremony in which an embellished cover (chaddar) is placed over a coffin.

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

211

There is also the pen-down strike and the tool-down strike, where workers go

to work but do not work, and the wheel-jam strike in which transport comes

to a complete halt: "Earlier, a five-hour wheel-jam strike on Thursday night

disturbed the whole train schedule" (FP/L 18 May 1992: 3/2). Multiple-word

compounds are also frequently formed using the Latin preposition cum

('with') — the type is widespread in International English, but seems to be

particularly frequent in South Asian English both in Pakistan and in India:

"Dacoits-cum-rapists still at large" (FP/L 27 Mar 92:3/1); driver-cumsalesman (D 27 Jun 88:4/3); hired assassin-cum-dacoit (MN 28 Jan 87:3/1);

kidnapping-cum-robbery (M 18 Apr 90:1/6); palmist-cum-quack (N 20 Mar

89:4/3); and "Gul Muhammad starts work at 5 in the morning, at a small

workshop-cum-factory where they make marble tiles or chips or something.

He works as their odd-job man-cum-assistant-cum-peon-cum-chowkidar

[watchman]" (N 27 Oct 90:5/2).

Typical PakE compound verbs include:4 to airdash 'to depart quickly

by air', to head-carry 'to carry on the head' and to love-marry: "A youth,

who was taunted repeatedly by his kins for having love-married his girlfriend, shot and injured his aunt, uncle and two cousins at his house in Misri

Shah here on Friday" (D/L 30 Mar 91:2,4/4). Compound adjectives include:

country-made 'locally made', riba [interest] free, over-clever 'smart-alecky':

"When challenged by the young polling agent, the SHO [Station House

Officer] told her not to be over-clever and threatened to turn her out of the

station" (FP/L 26 Oct 90:3/4), and soft-cornered: "There are also reports that

some 'soft-cornered' Senators may also be inducted in the cabinet" (PO 26

Jun 90:12/2).5

4) For comparison, it may be noteworthy that in BrE the N+V type exists only as backformations (typewrite < typewriter).

5) There is a group of common hybridized PakE noun compounds (not included in Appendix

1) whose etymology is not always entirely clear. These include kochwan, kundiman, numberdar~lumbardar, and malgodown. A kochwan in PakE is the driver of a tonga, a horse-drawn

buggy: "It was, however, passers-by, cyclists, motorcyclists, scooterists, rickshaw walas, tonga

kochwans and wagon drivers who mainly responded to Edhi's clarion call" (N 27 Sep 91:5/8).

Qureshi (1989) labels kochwan (and alternate form kochban) as English and translates it as

'coach-driver'; Singh (1895/1983) translates the word as 'coachman' and calls it a corruption

of the English word. A kundiman in PakE is a person who cleans gutters; they are also known

as gutterwallas (N Eid Special 5 Apr 92:3/8): "Meanwhile, sewer cleaning work was carried

212

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

2.2. Affixation

2.2.1 Suffixation

Suffixation is a very productive category of word-formation in PakE.

Appendix 2 contains a select list of common PakE words formed through

suffixation. The list identifies words formed with English as the base word

as well as words with Urdu (or in a few cases a regional language) as the

base to which an English suffix is added.

English-based formations are in most instances unremarkable, in the

sense that they follow established rules of word-formation and could hence

be found in any variety of English. Some of the words, in fact, are cited by

the OED as rare or obsolete or forms used in British regional varieties of

English, e.g. evictee, collegianer ("a collegianer, was standing..." FP/L 19

Mar 92:16/6), oftenly, weighment, cowardness, and lecturership. It is

difficult to determine if words such as these are cases of colonial lag or new

formations, since historical information on PakE is lacking. The majority of

out through machines and kundimen thereby easing the problem of overflowing gutters in these

localities ..." (D 17 Jan 88:2/8). Kundiman is a combination of the Urdu word for hook

[kaanTaa], presumably after the hook on the end of the sticks with which sewermen clean, plus

the English morpheme -man. The OED defines the Anglo-Indian word lambardar as the

registered headman of an Indian village, formed from the English word number plus the

Urdu/Persian suffix -dar meaning 'possessor of. Whitworth (1885/1981) terms lumberdar a

corrupt form of numberdar. In Pakistan, both forms of the word are still in use and refer to

either a low-level government official or a prisoner in the so-called lumbedari system: "One

cannot expect a banker in the private sector to allocate loans on the recommendation of a

lumberdar, a low level government official" (N 5 Apr 92:6/1) and "Juvenile prisoners have

provided harrowing details of crimes committed either by or at the behest of lumberdars, the

so-called 'responsible' people appointed from among inmates to share the burden of administration" (N 27 Mar 91:6/1). Like many Urdu borrowings in PakE, numberdar can be pluralized

either with an English or an Urdu (Persian) -an plural: "Political gatherings like the convocation of numberdaran was held a couple of months back which ushered in thousands of

numberdars and their supporters" (NS/L 5 Apr 91:7/7) — see Baumgardner, Kennedy and

Shamim (1993) for a detailed discussion of the grammatical aspects of Urdu borrowings in

PakE. Finally, the PakE word malgodown means a warehouse or store for goods: "They were

standing on the bye-pass road near Railway malgodown when Muhammad Zahid reappeared on

a motorcycle along with two others" (PT 29 Jul 90:2/6). The word is composed of the Urdu

word mal 'goods' plus the word godown, which the OED and Yule and Burnell (1886/1985)

cite as probably coming from Malay gadang via Telugu and/or Tamil; earlier gadangs were

often subterranean, hence the folk etymology godown.

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

213

the English-based forms in Appendix 2 do not appear in the OED or in

major AmE dictionaries; in some instances, however, related forms are

attested — technicalize, for example, is cited in the OED, while technicalisation is not. In the following discussion of suffixation, I shall concentrate

on those words which have taken on special significance in the Pakistani context.

As can be seen from Appendix 2, the -ee suffix is very productive in

PakE. According to Marchand (1969:267), it originated in Anglo-Norman

law terminology, but it is now found in legal, quasi-legal as well as in

whimsical contexts (Bauer 1983: 244). A number of the PakE -ee words are

legalistic in tone and are associated with the "law and order situation" —

abscondee, affectee, afflictee, convictee, remandee, rewardee, and shiftee.

Others are found in the quasi-legal context of the "world of work": awardee,

recommendee, recruitee and promotee, while adultree is a whimsical usage.

Affectee is by far the most common PakE -ee formation, cf. blast affectees

(PT 13 Apr 88:1/1), canal breach affectees (M 17 Aug 90:6/3), earthquake

affectees (N 26 Jun 90:8/4), erosion affectees (FP/L 20 Aug 91:6/3), famine

affectees (MN 1 Jan 88:1/2), fire affectees (NS/L 2 Apr 91:8/6), flood

affectees (D/L 4 May 91:2,3/2), hail affectees (KM 8 Apr 87:3/1), investment

affectees (N 23 May 90:3/4), and riot affectees (MN 30 Aug 89:5/5), etc. A

special type of "riot affectees" are shiftees, or those affectees who must be

relocated to another area because of civil unrest: "Speaking on the occasion,

Mr Shahid Aziz, Commissioner Karachi, said that all the affectees would be

paid compensation. Each shiftee would get copies of the challan [order]

when they reach the new site and take possession of the plot" (D 26 Apr

87:1/7). The Gulf War also produced affectees: "Ejazul Haq Federal Minister

for Labour, Manpower and Overseas Pakistanis has assured the Kuwait

affectees of Pakistan that government was taking adequate steps for their

speedy return to Kuwait to facilitate their reappointments on the jobs they

were on before the Gulf war" (NS/L 3 Aug 91:8/3). As Pakistani journalist

Nasir Abbas Mirza has noted about the proliferation of this word: "Other

countries have people or populations; we have only affectees. There isn't

one among us who is not an affectee of sorts. Those who are too poor to

attract the wiles of fellow men are done in by nature" (N/I 22 Sep 92:6/2).

Within the context of the Pakistani Civil Service, a promotee is someone with less education (e.g. a diploma holder) who is first appointed in a

lower grade and is then promoted to a gazetted grade (17 or above) as

214

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

opposed to a person (e.g. a university graduate) who is appointed directly in

Grade 17 as an officer. Hence, promotee does not mean someone who is

simply promoted, e.g. from grade 6 to 7, or 17 to 18; it is a negative social

label which indicates that the promotee is not qualified for the position,

which he/she received on the basis of sifaarish or "influence". The Urdubased -ee formation sifarashee is similar in meaning; as the editorial of The

Nation (Lahore) of 28 May 1988 wrote: "That surplus workers have been

recruited is indicative of the excesses of political pressure or sifarish. In a

number of cases new posts were created to accommodate sifarishees". The

PakE word recommendee also carries the idea of political patronage (see also

related compounds shoulder promotee and sifaarishi promotee in Appendix 1).

With respect to the three basic types of -ee formations structurally

distinguished by Marchand (1969:267-8) (expressing a direct object,

prepositional object, and subject relationship, respectively) the PakE -ee data

shows that the majority of -ee formations are of the direct object type, but

there is a significant number of subject formations as well (viz. abscondee,

defectee, indulgee and optee). One of the limitations on the base of words

suffixed with -ee is that the base must be a verb (Bauer 1983:245). All of

the PakE -ee data in Appendix 2 meet this criterion except for one notable

exception — ad hocee, which is formed with an adjective base: "Ad hocees

[a part-time or temporary employee] for regularisation" (FP/L 23 Jul 89:4/8).6

Aronoff (1976:43) has noted that if a word already exists in a language, it is unlikely that another word with the same meaning will be

formed, a principle he calls "blocking". It is interesting to note that six of the

-ee formations discussed above were not "blocked" in spite of already

existing words: convertee (convert), convictee (convict), recruitee (recruit),

defectee (defector), abscondee (absconder) and indulgee (indulger). However, only two of these items — abscondee and defectee — occur with great

frequency in my database and could therefore be considered "institutionalized"

6) Bauer (1983:244) notes that absentee may have been derived from an adjective. I do not

have ad hoc used as a verb in my data base, but Simpson and Weiner (eds. 1989,1:153) cite it

as a nonce word in BrE. The adjective ad hoc is, in fact, quite prolific in PakE. There are ad

hoc teachers, ad hoc lecturers, ad hoc doctors, ad hoc lady medical officers, all the result of,

according to not a few Pakistanis, the ad hocracy (N 20 Sep 89:3/3) and the ad hocism (FP/L

24 Dec 90:2/3) of their government. The OED's (1989,1:153) first citation for ad hocism (1968)

is from a South Asian source.

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

215

(cf. Bauer 1983: 87-8). It is noteworthy that the proliferation of institutionalized PakE -ee words like affectee, afflictee, evictee, promotee, recommendee

and shifee has not gone unnoticed by Pakistanis themselves. Muslim (Islamabad) journalist N. A. Bhatti went so far as to suggest even more additions

to the ever-growing PakE -ee word stock: "As the law and order situation in

the country is the burning topic of the day, it occurred to me that we must

not miss the opportunity of introducing words such as bombee, swindlee,

tear-gassee and lathi-chargee" (Bhatti 1991:7). The fact that some of these

lexemes duplicate existing BrE words may be taken to illustrate the predicament of ESL writers who, not having the full lexicon available, may coin

words on occasion (Gorlach 1989:297-8).

Another suffix which is very productive in PakE is -(i)er with a wide

rank of meanings: denter (FP/L 21 Jul 91:2/5), daily wager (NS/L 14 Feb

92:9/5), eveninger (PO 3 Mar 90:1/5), eve-teaser (M 26 Jun 90:3/4), historysheeter (M 22 Apr 90:1/7), forklifter (MAG 6 Feb 92:14/5), morninger (DN

4 Jun 88:1/4), neighbourer (NS/L 12 Sep 91:3/1), old-ager (D 2 Feb 88:8/6)

and one-dayer (N 25 Sep 91:11/2). A denter is a person who "removes"

dents from a car: "I had to go to my denter to get the car repaired but when

I reached the workshop, it was being closed down" (FP/L 7 Mar 92:7/3). A

denter in AmE is a "bodyman", "metalman", or the more formal "auto body

technician". To dent in PakE has therefore been extended to mean, in

addition to putting dents into something, taking dents out of something:

"Ustad Baba says that he wants Noor's life to be secure, so he pays extra

attention to him while teaching him the art of denting" (FP/L 15 Apr 91:5/6).

Consider also N. A. Bhatti's (1991:7) comments on denting'. "... my car

mechanic's detailed repair and maintenance bill ... had an item 'Denting. Rs

200'. What the hell, a foreigner might think; the chap bashes in your car and

charges you Rs 200 for it! However, if he knew even a smattering of

Penglish [a blend of P(akistani)+English], he would understand that 'denting'

in this country does not mean causing a dent but removing it".

A daily wager is a person who works on a daily-hire basis and an eveteaser a youth who harasses girls (cited by Barnhart 1984:54); a housejobber is a doctor serving an internship (a house job) and an old-ager a

'senior citizen'. A one-dayer is a one-day cricket match, and morningers and

eveningers are newspapers published in the morning and evening, respectively: "After completing 16 months of publication, The Pakistan Observer,

216

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

hitherto an Eveninger of Islamabad, despite heavy odds, is very shortly

switching over to full-fledged Morninger of standard size with enlarged

editorial set-up and expanded circulation network" (PO 3 Mar 90:1/5). A

history-sheet in PakE is a criminal record (cf. BrE charge-sheet and AmE

rap sheet/yellow sheet); hence a history-sheeter is a person with a criminal

record: "I am told that nearly 10 to 15 per cent of the Members of the

Punjab Assembly are history-sheeters which means that police stations must

have record of their criminal activities" (M 24 Aug 91:4/6). Collegianer,

comperer, forklifter and neighbourer are again formations "which were not

"blocked" (Aronoff 1976:43), since -er-less variants exist (collegian,

compère, forklift and neighbour). The feminine form of the -er suffix is used

with more frequency in PakE than in native varieties of English. In the

following tender notice, gender is in fact marked twice: "Sealed tenders, only

from female contractress, are invited for running canteen at hostel F.J.M.C.

Lahore" (FP/L 18 Jun 90:4/8). Derivations with -ess and "lady" compounds

are often used interchangeably. An article in the Pakistan Times of 4 July

1987 carried the headline "Lady teacher abducted, mother looted in Sialkot";

the article went on to relate: "The accused also allegedly deprived Noor

Jehan, mother of the abducted teachress, of gold ornaments and cash of Rs.

77,000 at gun point" (PT 4 Jul 87:8/1).

The suffixes -ian and -ite are utilized in both English-based as well as

Urdu-based formations primarily to indicate affiliation with an organization,

political party, educational institution, or residence in a particular Pakistani

city. A Pipian or PPPian is a member of the Pakistan Peoples' Party, a

Jhangian is a resident of the city of Jhang, which is located in the Punjab

north of Lahore, and a Formanite is someone affiliated with Forman

Christian College in Lahore. The suffixes -il-y, -ish, -less, -ness, -like, -ly,

and -wise are used in both English- and Urdu-based formations as primarily

descriptive words, hence maliky means 'like a malik, or chief; wheatish

(also in IndE) indicates the color of wheat and is frequently used in matrimonials in the classified section of newspapers to describe skin color:

"UNMARRIED Sunni, 30 years, B.Sc, Urdu speaking, medium height,

wheatish complexion, household master, requires Sunni, independent,

educated and established with complete home address and telephone number" (D 20 Feb 87:12/1); meatless days are those days (previously Tuesdays

and Wednesdays) on which it was illegal to serve red meat; hijablessness is

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

217

the state of being without cover as applied to women in Islam: "Warning

against hijablessness of the face, body and legs, the notice listed eight types

of violation" (D/L 20 Apr 89:10/4); goonda-like is like a goonda, or thug;

and mohalla-wise is something which applies to a neighborhood (mohalla).

The suffixes -dom, -gate, -ise, -isation, -ism, -ist, -istic, -ocracy , and

-ship are often used with lexemes associated with particular political,

philosophical, or religious ideologies. Politics has added many neologisms,

both English- as well as Urdu-based, to the PakE lexicon, and a large

number of these — both English-based as well as Urdu-based — have also

been borrowed into Pakistani Urdu. It is often stated by Pakistani politicians

that there are no "isms" in Pakistan. The data in Appendix 2 contradict this

claim; every -ism formation has a direct or indirect political meaning:

brotherism and related Urdu-based biradirism refer to clan-dominated

politics, jobism to the practice of giving employment to clan members only,

and chaudryism (<chaudri), khanism (<khan), sardarism (<sardar), and

wadiraism (<wadera) to the rule of feudal lords in the Punjab, North West

Frontier Province, Balochistan, and the Sindh, respectively. The same applies

to the majority of the -ocracy lexemes: plotocracy refers to the practice of

awarding land to political cronies, begumocracy to the rule of a woman

(Benazir Bhutto), and waderacracy to the rule of Sindhi landlords: "The

source of all evils in our country — social, political or economic — is the

feudal system, the so-called 'Waderacracy' as opposed to democracy" (M 23

Jun 90:4/6). A number of the -ship lexemes also have political significance:

caretakership (as in "caretaker government"), headmanship, kingmakership,

Pathanship, and PM-ship (the abbreviation of "Prime Minister" + -ship). The

term upliftment (cited in the OED as chiefly subcontinental corresponding to

BrE/AmE uplifting) occurs with regularity in the phraseology of Pakistani

politics ("Tree plantation plays a vital role in the upliftment of the national

economy" [MN 20 Aug 87:3/2]) as does the term externment {to extern, or

expel, + -ment): "The Opposition in NWFP Assembly Wednesday strongly

criticised the PPP-led coalition government for serving externment orders on

IJI leader Senator Asif Fasihuddin Vardeg" (M 22 Jun 89:1:2).7 The related

"law and order situation" has also spawned a number of characteristic terms:

agitationist, hooliganist, kidnapocracy, kalashnikovisation, and the hybrid

7) See also the section on "Conversion" for other forms with extern.

218

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

dakoocracy (dakoo, Sindhi 'bandit'): "True Muslim society cannot come into

being without putting an end to feudalism, nor does the country need the

'dakoocracy' of a few over the masses" (NS/L 8 Aug 91:12/6). A related

example is the lexeme pointation (formed after the Urdu feminine noun

nishaan dehii 'pointing out, identification'). It is used to indicate that

someone furnishes the information which leads to the arrest of a suspected

person: "During investigation the accused disclosed that he along with his

other accomplices had committed many thefts in various parts of the city. On

his pointation police conducted raid and arrested Nadeem Khalid while their third

accomplice Mohammad Nawaz, a driver, managed to escape" (N 9 Jan 88:3/6).8

Finally, a substantial number of formations based on the word mullah,

or Islamic priest, all indicate the political influence of the mullah in Pakistan:

mullahdom, Mullahgate (after the Watergate scandal), mullahism, and mullacracry: "If Pakistan had an irreverent tabloid press, the scandal now

gripping Islamabad would have headline writers hopping with delight.

'Mullahgate', they could trumpet" (NS/L 13 Nov 91:12/2). The inclusion of

Islamic laws (the Sharia) in the civil code is another issue in the Pakistani

political context; the editorial of Dawn (Lahore) of 4 August 1990 thus

opined: "The enactment of an all-embracing Shariat Bill — 'Shariatisation'

as it is sometimes called — [is not] a simple matter". Shariatisation would,

according to many Pakistanis, lead to chaddarism, or the state in which

women must wear a chaddar 'cover'. Two related -ocracy terms are Allahcracy and shooracracy, the latter coined by the late Pakistani President Ziaul-Haq "to characterize his regime and give it a democratic veneer" (Lemay,

Lerner and Taylor 1988:81). Urdu shoora (from Arabic) means 'advice,

consent or council': "Foiling General Zia's attempt at imposing shooracracy

in the country is a significant achievement of MRD [Movement for the

Restoration of Democracy]" (N 9 Jan 88:l/5). 9

2.2.2. Prefixation

Prefixes in PakE are used most productively with Urdu bases. Again, as in

the cases of Urdu bases plus English suffixes, many of these word-formations have also been borrowed into Pakistani Urdu. Productive prefixes

8) See Kennedy (1993) for a full discussion of the PakE "law and order" lexis.

9) See Baumgardner (1996) for a further discussion of innovation in PakE political lexis.

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

219

include: anti-, as in anti-awami, or anti-people — both occur with regularity

in the rhetoric of the party out of power in Pakistan to describe the actions

of the party in power: "This objective could only be achieved if we make the

federation more strong and foil the conspiracies being hatched by the antiawami elements" (PT 30 Apr 89:1/4), anti-mullah (MAG 14 May 92:9/2)

and anti-Shariat ("He said that this decision was anti-shariat in spirit" [FP/L

23 Apr 91:12:4/5]); counter-, as in counter-fatwa: "Mufti Naeemi and a

number of Mullahs are embroiled in a strange controversy, bringing poor

Diana [the Princess of Wales] under the cross fire of fatwas and counterfatwas" (N 3 Oct 91:5/1); non-, as in non-Karachiite ("The Sindh government is maintaining the theory that Karachi police must be run by a nonKarachiite, having no experience of service in Karachi" [MAG 28 Sep

89:13/5]); and super-, as in super-chamcha (chamcha, literally 'spoon', also

means a 'sycophant' — "He also expressed pride in his capability of being

a super-chamcha" [PT Nov 89:10/8]).

The prefix de- is also very productive in PakE, often in instances where

BrE/AmE would use the prefix un-. Attested PakE forms include de-authorise: "The government, of course, could have de-authorised the Shariat Court

only by seeking cooperation from the Opposition in the passage of a pragmatic and unambiguous Bill on the subject" (N 11 Mar 92:6/5); de-block (D

3 Aug 89:4/2); de-confirm: "Sindh inspector general of police has deconfirmed 23 inspectors who were promoted out of turn" (NS/K 18 Dec 91:3/4);

de-friend: "DEAR PERPLEXED, If I were you, I would de-friend her" (Y 24

Sep 91:5/l-advice column); de-load: "List of telephone numbers F-I to be

converted into other numbers due to deloading of F-I exchange" (PT 4 Aug

86:5/5); de-market (N 12 Apr 91:9/1); de-recognise: "He asserted that

substandard institutions would in no way be recognised. Those not maintaining the standard would also be derecognised, he added" (D 29 Apr 87:6/2)

and the headline "Derecognition of IEP [Institute of Engineers of Pakistan]

condemned" (N 23 Jul 88:2/4); and de-shape: "Good News for Woolies! No

more stretching and deshaping of your woolen clothes" (D/L 23 Nov 88:1/1).

Note that de- coinages are also considered to be a hallmark of IndE (cf.

Nihalani, Tongue and Hosali 1979); it would be interesting to see which of

the items are shared.

220

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

2.3. Conversion

As in other varieties of English, conversion (or zero derivation) is a very

productive word-formation category in PakE. In conversion, one part of

speech changes to another, and according to Bauer (1983:226) for the most

part "conversion is a totally free process [which] any lexeme can undergo".

The majority of PakE conversions are adjective-to-noun. A front-page

headline of The Nation of 22 April 1991 read: "Corrupts to be removed from

PML [Pakistan Muslim League]". The vast majority of the conversions in

my data would not normally be found in either BrE or AmE. The above

headline would most likely read the corrupt in either variety. Other PakE

noun conversions from adjectives which occur with great frequency are

faithfuls'. "The number of those Pakistani faithfuls who will perform Umra

[lesser pilgrimage] in the Holy month of Ramzan will cross the figure of

120,000 this year" (PO 7 Apr 90:1/2); influential: "A gang of students led

by the teenaged son of a Sindhi influential shot dead a classfellow" (NL Feb

92:62/1); poors: "Political and social sectors have demanded the Government

to provide shelter to poors" (N 4 May 87:8/6); and unfaithfuls: "The resolution said that JUP was not the party of unfaithfuls and would stand beside

the Muslim League leadership in the hour of need" (N 11 May 92:1/3).

Adjective-to-noun conversions also occur in the singular; a headline from

The Nation of 7 March 1992 (2/4) read: "Every landless to be given 25

acres". Other attested conversions include: ad hocs (N 27 Feb 92:2/7),

abnormals (M 11 Feb 92:7/6), affluents (M 16 Apr 91:4/4), anti-socials (S

23 Oct 86:16/4), blinds (D/L 9 Jul 89:3/1), deads (N 13 Feb 88:1/7),

decadents (N 13 Feb 88:1/7), destitutes (N 13 Feb 88:1/7), downtroddens

(FP/L 9 May 91:2/4), formers (FP/L 9 May 91:2/4), fraudulents (FP/L 26

Feb 92:5/8), gratefuls (M 24 Aug 89:4/7), injureds (N 13 Nov 87:2/5), mads

(D 7 Feb 88:5/2), nears and dears (NS/L 9 Apr 91:3/2), olds (D 22 Dec

87:2/2), populars (M 24 Oct 88:5/7), respectables (PT 17 Oct 86:1/4),

responsibles (FP/L 10 Mar 92:5/1), rurals (N 11 Jan 91:12/4), slains (FP/L

1 Aug 90:1/3), and well-offs (M 19 Jun 90:3/5).

Sign is a PakE conversion from a verb to a noun. A University of

Balochistan Vehicle Request Form reads: "The user of the above Vehicle is

requested to please sign the log book on the completion of journey immediately, otherwise the indentor will be held responsible for the consequences

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

221

due to non-sign of the log book". A verb-plus-particle-to-noun conversion is

eat-out, an outside eatery: "Yet the administration has gone for bringing an

early end to city life by ordering closure of shops and business concerns at

8 pm. The only exemptions are restaurants, eat-outs, beetle and cigarette

shops and, of course, pharmacies" (FR 12 Jul 91:42). The noun conversion

made-easy comes from the phrase "x made easy" as found in titles of books

such as "Mathematics made easy": "Students bring out publications on

various occasions and collect advertisements from various regular advertisers.

These publications vary from souvenirs on college functions to made-easies

of different subjects" (MAG 14 Sep 89:8/5). Finally, the frequently-occurring noun conversion incharge also comes from a phrase, "in charge": "The

IG [Inspector General] ordered the arrest of the incharge of the Punishment

Cell and suspension of ten others, including security guards" (DE 23 Jun

90:1/3) and "The meeting was attended by all the zonal and sector incharges

and central leaders..." (NS/L 22 Mar 92:5/6).

PakE verb conversions are derived primarily from nouns. To extern from

the BrE noun extern ('outsider, one who does not belong to, reside in') is a

representative example (see also externment above): "The teaching staff of

the university expressed their sense of shock and distress over the fact that

some students externed from the university had forced their way into the Sir

Syed Hall" (PT 6 Jul 87:3/2). A related example is to ouster: "He said

though his decision to ouster NPP was unconstitutional and illegal, but he

would not appeal against the decision and he was very happy with the

decision" (FP/L 20 Mar 92:1/6). Noun-to-verb conversions from the aviation

industry include to aircraft and to airline: "Plans to aircraft the ailing

Khudai Khidmatgar leader, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, from New Delhi to

Peshawar tomorrow have been deferred in view of the sudden and unexpected improvement in his condition on Monday" (M 4 Aug 87:8/8) and "A new

destination, Khusdar, is being airlined for the first time with Karachi and

Quetta" (N 27 Oct 87:12/4). The "law and order situation" has yielded to

arson from a noun, as in "They questioned the Prime Minister as to how

many terrorist were killing, looting and arsoning the properties of Mohajirs

[immigrants from India] in Jamshoro and other parts of interior Sindh?" (M

2 Jun 90:8/8), as well as to chargesheet from the BrE noun chargesheet: "As

many as 40 employees of engineering branch of Municipal Corporation were

charge sheeted by the Mayor following different charges" (D 28 Feb 88:5/1).

222

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

When Benazir Bhutto married in 1987, the popular magazine Mag published

an article entitled "Benazir Better Halved" (6 Aug 87:16/1). Other attested

PakE noun-to-verb conversions include: to deadline (FP/L 5 Aug 91:4/1), to

firecracker (WP 4 Jan 91:8/4), to foulmouth (N 1 Dec 91:10/1), to hostage

(N 21 May 91:2/5), to pilferage (NS/L 30 Aug 91:20/6), to pot-shot (WE 28

Jun 91:3/2), to red-carpet (N 21 Feb 92:4/4), and to slogan (N 31 May

89:1/1).

A number of conversions are found in PakE which the OED cites as

archaic, rare, or obsolete usages, e.g. the lexeme aghast as a verb, labeled

"obsolete" (1596 citation). "What actually aghasted and infuriated me was

the fact that the food which could not occupy the stomach was treated in the

most abominable fashion" (MAG 5 Dec 91:46/5). Similarly, the OED cites

to coy as archaic (1828 citation): "There is a powerful lobby in Pakistan

today that says we should detonate a nuclear device and we should not coy

about it" (N 28 Apr 91:1/5), and to scarecrow meaning 'to frighten' (1593

citation) as obsolete: "Here're some more of awe inspiring, hair raising,

blood chilling and flesh creeping examples to scarecrow you away" (M

Magazine 28 Jun 91:7/4). Similar usages include: to creed (FP/L 22 Feb

92:16/2) [OED, 1652, obsolete]; to disrepute (NS/L 22 Mar 92:2/2) [OED,

1697, obsolete]; to influx (N 19 Jan 88) [OED, 1684/1710, obsolete/rare]; to

mischief (N 18 Jan 89:2/2) [OED, 1836, archaic]; to public (N 2 Dec 87:8/2)

[OED, 1570, rare/obsolete]; to sacrilege (FP/L 15 Feb 92:4/2) [OED, 1866,

rare]; to sympathy (PT 4 May 91:1/1) [OED, 1634, obsolete], to threat (NS/L

21 Jul 91:2/5) [OED, 1642, obsolete]; and to true (FP/L 17 Aug 91:16/4)

[OED, 1888, rare/obsolete]. It is unclear, as previously stated regarding PakE

suffixed forms, whether these are examples in PakE of neologistic conversions or colonial lag.

PakE also contains a substantial number of Urdu or bilingual noun-toverb conversions, i.e. Urdu nouns which are shifted to verbs in PakE. The

most well-known example of this process is the PakE verb to gherao, which

means 'to surround in protest': "Later several hundred persons gheraoed

Market Police Station, demanding immediate arrest of the robbers" (D 1 Feb

88:3/4). Gherao comes from the Urdu noun and verb with the same meaning

and is cited in both the OED as well as the Concise Oxford Dictionary of

Current English (Allen, ed. 1990). Another common bilingual conversion is

to challan (see also challanable discussed above). A challan (cited also in

W O R D - F O R M A T I O N IN PAKISTANI E N G L I S H

223

the OED) is a citation: "The traffic police in its campaign challaned 237

drivers for violation of traffic rules and recovered more than Rs 18,000 as

fine" (NS/L 15 May 91:4/5). However, any Urdu noun can undergo the

process. A 1992 headline in Dawn (Lahore) read: "Two-year remission for

convicts who 'hifz' [memorize] Quran"; the article went on to explain: "The

Punjab Government has decided to grant two years special remission to each

prisoner learning the Holy Quran by heart during their confinement in jail

throughout the province" (D/L 28 Mar 92:2,4/5).10

The adjective-to-verb conversion to tantamount occurs frequently in

PakE: "Ms Bhutto too cannot accept such an option as that tantamounts to

an open admission of guilt and fear of punishment which will destroy her

party forever" (M 17 Aug 90:1/3) and "The critical remarks...were denied as

tantamounting to undermine the personality of the said Deputy Mayor" (N 6

Mar 90:2/1). The OED cites tantamount first as a verb (1628), then as a

noun (1637) and subsequently as a predicate adjective (1652), its current use.

Other examples of PakE adjective-to-verb conversion include fast asleep: "A

pir [spiritual guide] stabbed to death one Sajjad Ahmed and his mother in

Mohallah Abbaspura at the time when the deceased were fast asieeping" (NS/L

27 Feb 92:8/1) and roughshod: "Speculation about rough-shoding over the

Army's dissent is a canard spread by interested quarters" (N 12 Mar 92:6/5).

10) A related process is one in which the suffix -fy can be added to the imperative form of

an Urdu verb to produce a hybrid verb, hence jhoomofy is formed from jhoomo, the imperative

of jhoomna 'be enraptured, sway to and fro', plus the suffix -fy: "They all jhoomofy and roll

on the scented gao-takias [round, elongated cushions] in ecstasy" (FP/L 10 Jun 92:7/4).

Compound Urdu verbs can also undergo this process; seedha karnaa is Urdu for 'to correct, set

right, chastise'. The imperative form seedha karo serves as the base for this -fy formation:

"They really need to be seedha karofied too" (FT 4 Apr 91:24/5). To ratafy is formed from the

imperative form {rata) of the Urdu verb ratnaa meaning 'to cram (AmE) or mug up (BrE) for

an examination' plus the suffix -fy: "The paper was very simple. Students used to 'ratafying'

could not do it because one had to use one's brain" (N 13 Feb 90:7/6). Rattalization (rata + l

+ -ization) is the noun form of ratafy: "There is a common saying that 'rattalisation is the best

preparation for the matriculation examination'. If the students start appearing in separate exams

then they are going to forget the learning very soon as the 'ratta' does not last long" (HO 15

Oct 91:13/1). Finally, other suffixes are sometimes added to Urdu nouns in order to create new

formations. The Urdu word for tyrant is hilakoo; during the Persian Gulf War the following

sentence appeared in MAG in reference to Saddam Hussain: "Don't Let Him halaku-ise

Baghdad" (14 Feb 91:10/1). For a full treatment of bilingual conversion and related forms in

PakE, see Baumgardner (1992).

224

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

Urdu adjectives can also be shifted. The adjective sabakdosh in Urdu means

'unburdened, absolved of responsibility', hence the adjective-to-verb form to

sabakdosh: "He has announced that he is more than eager to 'sabakdosh'

himself from the 'farz' [responsibility] of having her well-settled in matrimony" (Y 11 Feb 92:9/2). A PakE adverb-to-verb shift is up-hill: "He maintained that the image of the country had been up-hilled at international level

as a result of recent elections, and Pakistan was being ranked among cultured

countries" (N 20 Jan 89:12/2).

2.4. Back-formation

Back-formation, according to Bauer (1983:64), "is the formation of a new

lexeme by the deletion of a suffix, or supposed suffix, from an apparently

complex form by analogy with other instances where the suffixed and nonsuffixed forms are both lexemes" (cf. Pyles and Algeo 1982:277; Quirk et

al. 1985:1579).

Typical PakE back-formations include: to character-assassinate from

"character assassination": "To character assassinate, demean and belittle the

other seems to be a necessity for our politicians" (WP 4 Jan 91:8/3); to

loadshed (N 16 Jun 91:2/3) from "loadshedding" (the temporary curtailment

of electricity); to metal-detect from "metal detector"; and to thumb-impress

from "thumb impression": "Under the Qanun-e-Shahadat (Law of Evidence),

1984, lady lawyer preparing a document cannot attest it as a complete human

being; she has to call the illiterate peon to thumb-impress the attestation"

(FP/L 12 Aug 89:5/6). Other PakE back-formations, such as to scrute (FP/L

9 Feb 92:16/1) from "to scrutinize" or "scrutinization" and to renunciate

from "renunciation", are attested in the OED as seventeenth, eighteenth and

nineteenth century usages, but cited as now obsolete or rare: "Leaders of the

Minorities Front for equal rights have urged the government to enforce

special law against, as they alleged, current tendency of renunciating their

religion by the Christians for personal gains" (M 8 May 90:3/3). Again, it is

difficult to tell in such cases whether words such as these are instances of

colonial lag or new back-formations. If, however, English literature from

these centuries is still read and "memorized" in PakE classes, as Kennedy

(1993) has pointed out, then it is likely that obsolete words like to renunciate

are older formations. It is such usages, as Husain (1992) has also pointed

out, that give PakE its stilted, archaic style.

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

225

2.5. Clipping

In clipping, part of a word is removed either from the beginning (foreclipping), middle (mid-clipping), or end (hind-clipping); the clipped form

retains both its form class as well as its meaning, although there may be a

change in stylistic level from more to less formal (Bauer 1983: 233). Supple

is an institutionalized hind-clipping meaning 'supplementary examination';

the editorial of The Nation (Lahore) of 1 April 1989 wrote: "Exams in many

universities are in arrears because students (not the studious type because

they don't count) get them postponed. Pakistan has given a new word to the

world of academics: the 'supplees'. A student can be endlessly taking

supplementary exams because of the student power behind him". Other

established PakE compounds with clipping include: admit card <

admitt[ance]: "A large number of parents also visited the college but left in

disappointment, without collecting admit cards of their sons and daughters

for the coming examination" (MN 23 May 1990:5/4); bio-data <

bio[graphical] (FP/L 1 May 91:12/2); Cantt < cant[onment] (MN 23 May

90:5/7); copy < copy[book] (NS/L 28 Mar 92:8/5); gynae hospital/ward/unit

< gynae[cological] (NS/L 16 Oct 91:3/1); homoeo college < homoeo [pathic]

(FP/L 4 Feb 92:8/6); kleshy < Klash[n]i[kov] (WE 7 Jun 91:8/1); and Thanks

God < Thanks [be to] God (MAG 16 Oct 86:41/5). Common Urdu clippings

found in PakE include Pak < Pak[istan] (MN 9 Jun 88:6/3); Pindi < [Rawal]pindi, city near Islamabad (MA 26 Apr 90:4/5); Muj < Muj[ahideen], Afghan

resistance fighters (FT 23 Apr 92:24/6); and naka < naka[bandi] 'cordon,

blockade': "Receiving a tip-off, a raiding party held a naka at 3.30 am 200

yards from the Indian border" (N 16 Jun 90:12/3).

2.6.

Abbreviations/acronyms

In the word-formation process of abbreviation, two or more words are

reduced to their initial letters or syllables and are pronounced as individual

letters; acronyms are similar to abbreviations, except that the resulting

letters/sounds are pronounced not as individual segments, but together as a

word (Bauer 1983:237). Some common PakE abbreviations are: CCI <

"Chamber of Commerce and Industry" (MN 13 Jan 91:8/7); d/o < "daughter

o f ("In another incident a young girl Rabia Bibi d/o Karim jumped into

226

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

Lower Jhelum Canal" [D/L 2 Jun 90:4/7]); f/o < "father of (N 3 Nov

90:10/8); FIR < "First Information Report" (FP/L 9 May 91:1/2); m/o <

"mother o f (N 2 Apr 92:3/5); NOC < "No Objection Certificate" (N 10 May

90:6/1); PBUH < "Peace Be Upon Him" (N 28 Sep 91:12/5); PO < "Proclaimed Offender" (NS/L 31 Mar 92:9/4) — a calque from Urdu ishtahari

mujrim; r/o < "resident o f (N 2 Apr 92:2/1); s/o < "son o f (N 24 Apr

91:4/6); SHO < "Station House Officer" (DE 26 May 90:8/3); TA/DA <

"Travel Allowance/Daily Allowance" (N 20 May 91:6/3); SM (and ASM) <

"(Assistant) Station Master" (N 6 Jan 90:1/5); and w/o < "wife o f (D/L 2

Jun 90:4/7). Urdu abbreviations used in PakE include the Arabic expressions

RA < Raziullah Anha 'God is pleased with him' (FP/L 23 Jul 91:3/2) and

SAW(S) < Salalaho alehe wasalam 'Peace be upon him' (N 25 May 90:4/6).

Established PakE acronyms include WAPDA < "Water and Power Development Authority" (FP/L 23 Jul 91:3/2) and WASA < "Water and Sanitation

Agency" (FP/L 23 Jul 91:3/2).

2.7. Blends

A blend, according to Bauer (1983:234), is "a new lexeme formed from

parts of two (or possibly more) other words..."; Marchand (1969:451) for

that reason defines blending as "compounding by means of curtailed words".

Algeo (1980) further classifies blends according to whether they are formed

according to the processes of overlapping and/or clipping. PakE blends

formed by overlapping include bushirt (< bush + shirt), where the sound [ʃ]

in both words overlaps to form the blend: "The prices of cotton shirt (boy)

and cotton bushirt (boy) ...showed lower increases of 5.3 percent and 5.6

percent during 1986-87" (Annual Report 1986-87, State Bank of Pakistan: 126). Another blend is flitterati < flitter + literati — " There was even

a sprinkling of the 'flitterati' people who spend their lives flitting from one

city to the next attending parties" (NS/L 11 Nov 91:2/5).

Cholestratti < cholesterol + glitterati (itself a blend in BrE and AmE <

glitter + literati) is another playful PakE blend with partial overlapping (-er-)

and clipping (hind clipping of cholesterol and fore-clipping of glitterati),

which is attributed to Pakistani humorist Khalid Hasan, who avers that some

Pakistani glitterati should probably be called this because of their eating

habits. Another such established blend is Lollywood < hind-clipping of

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

227

Lahore + fore-clipping of Hollywood. The majority of Pakistani movies are

made in Lahore: "The movie is a refreshing change from the run of the mill

Lollywood melodramas" (Y 10 Sep 91:9/1). Popular Pakistani magazines are

also filled with reports of Bollywood stars (MAG 26 Sep 91:42/5) as they are

known in India where Bombay is the center of Indian film-making. So-called

"sandwich words" are blends in which a word is inserted into another with

partial overlapping. Three socio-political PakE blends of this type include the

Urdu-English blend Islumabad < Urdu Islamabad + inserted English slum

(PO 28 Jan 90:2/1), politricking < politicking and inserted trick (FT 15 Mar

90:1/2), and refraudum < referendum and inserted fraud: "Then the selfrighteous dictator Gen Ziaul Haq was the perpetrator of the biggest rigging

in the referendum, popularly called 'refraudum'" (M 23 Jun 91:5/3).

PakE blends which involve only clipping with no overlap include the

common hybrid blend gymkhana and hydel, an English blend with hindclipping of hydro and electric. "The World Bank is still ready to finance

hydel power projects because of the western bias against atomic energy"

(FP/L 19 Sep 89:6/1). Hawkins (comp. 1984) defines a gymkhana as a sports

meeting or sports club: "The incumbent managing committee of the Lahore

Gymkhana may soon face a move of no confidence because a prominent

political figure was allowed to use the club's facilities without being a

member" (NS/L 20 Jul 91:2/6). Lewis (1991), the OED, Whitworth (comp.

1885/1981) and Yule and Burnell (comps. 1886/1985) all analyze gymkhana

as the possible combination of the hind-clipping of gymnastics (or gymnasium) plus the fore-clipping of the Urdu word gend-khana, or 'ball-house'.

Two political terms involving hind-clipping of the first morpheme and foreclipping of the second are consembly < constituent + assembly ("Call for

New Consembly on Party Basis" [D 9 Dec 87:5/6]) and coup-gemony < coup

d'etat + hegemony, a term coined by the late Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: "the

greatest threat to the unity and progress of the Third World is from coupgemony" (MAG 6 Jul 89:9/1,4).

In some blends only one morpheme is clipped. PakE blends with hindclipping of the first morpheme include by-polls < by-election + polls (PT 28

Dec 90:5/3); parawise < paragraph + wise (FP/L 6 Aug 91:3/1); photomachinist < photocopy + machinist, the person who makes photocopies in

Pakistani offices and businesses (N 9 Dec 87:2/6); and telemoot < television

+ moot [meeting]. Blends with fore-clipping of the second morpheme include

228

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

cricketomacy < cricket + diplomacy and freeship <free studentship. Pakistani

and Indian politicians use what the Pakistani press calls cricketomacy when

they attend cricket matches between the two rivals to show that the political

channels between the two countries are open (D/L 6 May 1992: 8/8) The

Handbook of Universities of Pakistan (1987:289) explains a freeship in the

following manner: "The Vice-Chancellor awards each year full or half

freeships to deserving students. A full freeship means total remission of the

tuition fee of Rs. 200 per annum and half freeship means remission of half

of the tuition fee i.e. Rs. 100 per annum". Finally, there is a class of PakE

blends in which a middle element is deleted, for example articleship <

article + of+ apprenticeship, in which both the word o/and the fore-portion

of the second morpheme are clipped; Pakistani firms advertise for employees

with articleships, i.e. a certificate which shows one has fulfilled an apprenticeship (PT 2 Jan 91:3/8). Unikarian (< University of Karachi + -ian) is

another such blend; here the word of plus the hind-portion of the first

morpheme are clipped and the suffix -ian is added: "Unikarians have also

helped their University in building a school for the children of University

employees and in some other projects" (TR 1 Oct 91:11/2). Similarly,

students at King Edward Medical college in Lahore are called Kemcolians <

King Edward Medical College + -ian, in which all but the first letter of the

first three words are hind-clipped + hind-clipped college + -ian. In some wordformation frameworks, these last two words would be classified as acronyms.

3.

Discussion

We have seen from analysis of the above data that PakE conforms for the

most part to established morphological rules in English, i.e. that it follows

what Katamba (1993:72) has termed rule-governed (vs. rule-bending)

creativity. Except for those instances where an Urdu element is involved in

the word-formation process, the vast majority of the lexemes discussed

above could be found in any variety of English. We have, however, seen

some cases of "rule-bending": (i) the creation of certain words was not

blocked (Aronoff 1976:43) by the presence of an already existing word, e.g.

abscondee for "absconder", collegianer for "collegian", defectee for "defector" and neighbourer for "neighbour"; (ii) instances of "rank reduction"

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

229

(Kachru 1983:136), where liquor bottle and matchbox are created from

"bottle of liquor" and "box of matches" in spite of the potential resulting

semantic confusion; and (iii) the use of an adjective as an -ee derivational

base, as in ad-hocee. The data also contains lexemes, which, while they

"accord with the norm" of English word-formation, violate some other

related constraint, for example, (i) the use of a Germanic rather than a

Latinate base in -ism derivations, e.g. brotherism, buddyism, jobism and

unclism, (ii) the occurrence of pleonastic compounds such as bed sheets and

challan ticket and (iii) the extensive use of cum in contexts where "it is the

combination of the particular two elements rather than the pattern that makes

the word unusual" (Gorlach 1989:300). Instances of such "violations" can

also be found in native varieties of English, but not to such a degree. Hence,

it would be accurate to say that Katamba's (1993: 72) rule-bending creativity

applies in only a minority of cases in the PakE data; the vast majority of

words discussed above conform to established patterns of English wordformation.

This is precisely the conclusion drawn in two comparative studies of

word-formation processes in English as a Native Language (ENL), English

as a Second Language (ESL), and English as a Foreign Language (EFL)

varieties. Gorlach (1989) found few differences between the two former

types of Englishes; his later study on emigrant Englishes (Gorlach 1996)

reached a similar conclusion. The author does note, however, that in ESL

varieties [like PakE] there "are frequently more 'exotic' [formations] as a

consequence of a much looser understanding of the underlying word-formation rules" (Gorlach 1996:130). That this is the case is, however, to be

expected in such a language contact setting. English in Pakistan functions in

a multilingual context of use; therefore, any discussion of structural norms in

PakE must also include a consideration of linguistic rules in Urdu and the

other languages of multilingual PakE speakers of English. Take as an

example the propensity in PakE to convert freely adjectives to nouns {the

poors) and nouns to verbs (to firecracker) as discussed in the data above. In

Urdu, nouns can be shifted to a verb by the simple addition of a restricted

set of verbs to the noun; adjective-to-noun conversions are also common in

Urdu, and there are no structural restrictions on their use as there are in

English (Bauer 1983:230). This structural ease is surely a part of the UrduEnglish speaker's bilingual competence. Cook (1992), for example, believes

230

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

that bilingualism (or multilingualism) is not simply the sum total of two (or

more) linguistic systems. None of the languages of the bi-/multilingual will

be exactly the same as that of monolingual speakers of those languages —

the languages co-exist in a symbiosis where linguistic boundaries can be

extended. What we have here then is a set of structural norms which are the

result of a language contact situation, and studies from Weinreich (1953) to

Gumperz and Wilson (1971) to Kachru (1983) to Milroy and Milroy (1985)

have aptly demonstrated what happens to linguistic systems at all levels in

such contexts. Yet another factor in this symbiotic linguistic relationship

between the two languages is the fact that Urdu is replete with English

borrowings. The majority of the compounds found in the English portion of

Appendix 1, for example, are also used in Urdu, which certainly reinforces

their use in English. It is not inconceivable that some of these as well as

some of the hybrid compounds in fact originated in Urdu.

The acceptability of these PakE lexemes — and the rise of an endonormative standard PakE — will of course ultimately depend upon the

acceptance of educated users of the variety itself. As Greenbaum (1996: 243)

has pointed out:

That English in South Asia has acquired its own characteristics cannot be

disputed. ... What is in dispute is the acceptance of the national characteristics

and their institutionalization. By acceptance I do not mean approval by native

speakers of English. Speakers of English in South Asian countries have to

become sufficiently self-confident and assertive about their own national

varieties. They do not require — and they will not receive — legitimization

by outside bodies.

And regarding the future of emigrant languages in general, Görlach (1996: 137)

further observes:

The stigma of local forms of English will disappear, with New Zealand, South

Africa, and the Caribbean following the lead of the U.S., Canada and Australia where national standards of English are already well-established. This

process will take much more time for, say, India or Nigeria, but there will be

no choice for these countries but to accept national norms at least for internal

communication.

In an earlier study (Baumgardner 1995), I reported on the results of three

questionnaires designed to measure the acceptability of various aspects of

PakE to Pakistani journalists, teachers and students. The results of that study

231

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

Table 1: Questionnaire acceptance rates: Urdu lexis

Lexical item

Total %

Male

Female

Clipping

Pak

Subtotal

.908

.908

.957

.957

.860

.860

Suffixation

goondaism

Ravian

Subtotal

.909

.842

.875

.971

.867

.919

.848

.818

.833

Compounds

lathi-charge

sehri-awakener

rickshaw-walla

police thanna

Subtotal

.948

.864

.858

.775

.861

.985

.898

.869

.800

.888

.912

.831

.848

.750

.835

Bilingual

conversion

to challan

to gherao

Subtotal

.874

.644

.759

.900

.671

.785

.848

.618

.733

Total

.851

.887

.815

showed that while on the one hand speakers of PakE were still to some

extent under the influence of the exonormative "colonial cringe" (Gorlach

1996: 124), a Pakistani norm is also beginning to emerge. One of the three

questionnaires discussed in that article was administered to 150 teachers of

English (80 females and 70 males) in teacher training sessions conducted in

the cities of Islamabad, Karachi and Lahore during the three-year period of

August 1989 to August 1992. That questionnaire contained a total of ninetyfour items, forty-eight of which were related to PakE word-formation. Tables

1 and 2 present the results for individual lexical items in that questionnaire

(only overall category percentages were discussed in the 1995 study).11

Table 1 shows the acceptability of nine Urdu-based formations (compounding, suffixation, conversion, and clipping), and Table 2 presents forty

11) Data in Tables 1 and 2 has been somewhat re-categorized from that in the 1995

publication in order to fit the word-formation framework of the present paper. The exact

wording of the questions which the subjects were asked to respond to was as follows: "In the

sentences below, please indicate by encircling YES or NO whether you consider the underlined

item part of Pakistani English".

232

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

Table 2: Questionnaire acceptance rates: English lexis

Lexical item

Total %

Male

Female

Compounds

guess paper

law and order situation

death anniversary

wheel-jam strike

bed tea

flying coach

pen-down strike

move-over

lady newscaster

soft corner

child lifter

marriage party

Kalashnikov culture

cent percent

eartops

heavy amount

eve-teasing

airdash

Subtotal

.981

.945

.919

.914

.891

.891

.879

.858

.857

.855

.847

.839

.819

.813

.724

.484

.459

.404

.798

1.000

.942

.927

.956

.885

.869

.921

.957

.867

.823

.913

.928

.913

.857

.753

.500

.446

.391

.825

.962

.949

.911

.873

.898

.886

.831

.760

.848

.887

.782

.750

.725

.769

.696

.468

.472

.418

.771

Clipping/

Abbreviation/

Acronyms

Wapda

SHO

admit-card

SM/ASM

CCI

Subtotal

.893

.875

.766

.727

.695

.791

.914

.956

.753

.746

.705

.814

.873

.794

.779

.708

.685

.767

Blends

biodata

bushirt

hydel

Subtotal

.964

.795

.453

.737

.942

.785

.523

.750

.987

.805

.383

.725

Conversion

charge sheet (v.)

undertrial (n.)

faithful (n.)

extern (v.)

tantamount (v.)

Subtotal

.759

.756

.705

.542

.528

.658

.869

.797

.753

.647

.671

.747

.649

.716

.658

.438

.386

.569

233

WORD-FORMATION IN PAKISTANI ENGLISH

Suffixation

Lexical item

Total %

Male

Female

sweeperess

denter

affectee

history sheeter

de-shape

eveninger

museumize

freeship

pointation

Subtotal

.872

.843

.838

.714

.617

.552

.528

.458

.370

.636

.910

.914

.911

.884

.671

.537

.552

.454

.391

.691

.835

.772

.766

.545

.564

.520

.416

.462

.350

.581

Total

.724

.765

.682

English items, including compounds, suffixation, conversion, clipping,

abbreviations, and acronyms (see Appendix 3 for the list of sentences in

which the items were presented). The last rows of the two tables present the

combined results of the Urdu lexis and English lexis questionnaires respectively.

Tables 1 and 2 are arranged according to the order of acceptance of

word-formation categories. In Table 1, we see that the order of acceptance

(ranging from 91% to 76%) was clipping (91%), hybrid suffixation (88%),

hybrid compounds (86%), and finally bilingual conversions (76%). These are

extremely high percentages of acceptance; there can be no mistake that these

are local Urdu-based innovations. Ironically, the one lexeme {to gherao) which

was accepted the least (64%) is the one found in not only the OED but also in

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English (Allen, ed. 1990).

In Table 2, the order of acceptance of English-based lexemes (ranging from

80% to 64%) is compounds (80%), abbreviations (79%), blends (74%), conversions (66%) and suffixation (64%). Most noteworthy here is the fact (as seen in

the total values at the ends of the tables) that these English-based forms

received less overall approval (72%) than the Urdu-based forms (85%).

Respondents are more inclined to accept "foreign" borrowed lexemes than

English ones which appear to them to be "unBritish". Overall acceptance of

most individual lexemes, however, is still high — remember too that these

are teachers. Again, as Bauer (1983: 88) has pointed out, the mere creation

of a lexeme is only the first step; what is pivotal is the form's ultimate

acceptance, or institutionalization, by the language community which uses it.

234

4.

ROBERT J. BAUMGARDNER

Conclusion

John Algeo, in a 1996 review of South Asian English (Baumgardner, ed.

1996), noted that in only one of the ten British and American dictionaries he

had consulted for the review (not the OED) had he found "South Asia"

appropriately defined. Algeo (1996:408) writes: