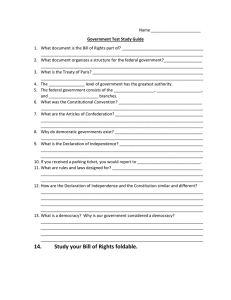

Democracy and State Capacity: Exploring a J-Shaped Relationship HANNA BÄCK* and AXEL HADENIUS** In this article we probe the effect of democratization on the state’s administrative capacity. Using time-series cross-section data, we find a curvilinear (J-shaped) relationship between the two traits. The effect of democracy on state capacity is negative at low values of democracy, nonexistent at median values, and strongly positive at high democracy levels. This is confirmed under demanding statistical tests. The curvilinear relationship is due, we argue, to the combined effect of two forms of steering and control; one exercised from above, the other from below. In strongly authoritarian states, a satisfactory measure of control from above can at times be accomplished. Control from below is best achieved when democratic institutions are fully installed and are accompanied by a broad array of societal resources. Looking at two resource measures, press circulation and electoral participation, we find that these, combined with democracy, enhance state administrative capacity. Introduction It is well known, from extensive experience, that we need a state in order to coordinate our activities and promote our welfare. Only the state, with its regulatory capacity, can furnish a number of services in general demand. In order to guarantee order, social peace, justice, and efficiency, society needs a functioning state. We need a state that works well—which does what it does in the right way, administratively speaking. But we also want a state that does the right things. By the latter we normally mean that the state conducts activities in accordance with the wishes of the citizenry. And the best way to ascertain the wishes of the citizenry is to apply the methods of political democracy. The ideal state, then, both functions well in an administrative sense and is democratic. Unfortunately, as we shall see, this combination has proved difficult to create. The global tendency over recent decades has been toward a growing gap between the two ambitions. The world has become more democratic, but the administrative capacity of states appears to have diminished. *University of Mannheim **Lund University Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions, Vol. 21, No. 1, January 2008 (pp. 1–24). © 2008 The Authors Journal compilation © 2008 Blackwell Publishing, 350 Main St., Malden, MA 02148, USA, and 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK. ISSN 0952-1895 2 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS When we examine the nature of the relationship between the two traits, we find a curvilinear, J-shaped pattern: The administrative quality is higher in strongly authoritarian states than in states that are partially democratized; it is highest of all, however, in states of a pronouncedly democratic character. This result holds when we study changes across time, and under control for a number of other factors. This points to the presence of a dynamic effect. At first, democratizing a state brings a cost: The administrative capacity of said state declines. Not until a fairly high level of democracy is reached can a successful convergence between the two traits take place. We conclude the article by developing an idea of how this curvilinear relationship could be understood. The argument in brief is that the administrative capacity of the state can be upheld through two types of steering and control: from above and from below. Authoritarian states, by virtue of their hierarchical structure and their repressive capacity, can be effective at maintaining a firm grip of the administrative apparatus from above. But when a state is democratized, this capacity deteriorates, and it is replaced only slowly by the controls exercised by various actors in society, which can be developed in open democratic states. The reason for this is that at low levels of democracy, the essential institutions of steering and control from below are only partially in place. Moreover, even if these institutions are eventually put in place, it takes time to build up the complementary resources among the citizenry, which are needed for making this form of societal involvement work. Looking at two resource measures, press circulation and voter participation, we conclude that these, combined with democracy, are important predictors of administrative advancements. This is the first study of the democracy–administrative capacity relationship to apply a composed measure of the latter phenomenon. Earlier inquires have been geared at one administrative aspect only, namely corruption. Moreover, we are the first to address this relationship by the use of time-series data, enabling us to observe dynamic effects, and to determine the direction of causality. Finally, we are the first to address the nature of the causal mechanisms at play. We propose a theory of two methods of steering and control, and data at hand seem to support vital aspects of this theory. Democracy and State Capacity: A Specification Democracy By democracy we mean political democracy in a liberal sense. Such a system requires that certain critical rights—and appropriate institutions—in respect of elections and political freedom be upheld. There are a number of indices with broad coverage, both geographically and temporally speaking, that can be used to measure the degree of democracy. Needless to say, these indices are formulated in different ways, DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 3 both conceptually and methodologically. Drawing on an assessment done in this area by Hadenius and Teorell (2005b), we employ a measurement of democracy based on an average of the two indices most widely used: the one provided by Freedom House and the one provided by Polity. In the case of Freedom House, however, we include only one component: political rights. The other component, civil liberties, bears among other things on the extent of corruption afflicting the various countries. As this is something we include in our measurement of administrative capacity, we must take care that this factor does not appear on both sides of the regression equation. State Capacity In speaking of a functioning state, we may have two things in mind. The first has to do with what we here term state-ness, that is, the capacity of the state organs to maintain sovereignty (as the ultimate third-party enforcer) over a geographical territory. This implies that the organs of the state uphold monopolistic control in a basic military, legal, and fiscal sense. In a functioning state, no competing power centers exercise control in these areas. In today’s world, in fact, there are “states” that exist in a juridical sense but that do not actually control their territory.1 In these countries, rebel forces and warlords exercise military and other forms of control over large parts of the national territory. It is this basal form of state-ness that is the first criterion for a functioning state. The second criterion has to do with how well the state organs are able to carry out their tasks. Here it is a question of how various activities undertaken by the state are actually accomplished. It is a question, in other words, of implementation capacity—something that different states may possess in varying degrees (Mann 1986). Thus, we are concerned here with the state’s administrative capacity in a broad sense. In states where this capacity is well developed, the public bureaucrats do their job in the best way.2 In addressing the problem of state administrative capacity, we are generally referring to the existence of a rational bureaucracy, in the fundamental Weberian sense. A rational bureaucracy recruits and promotes persons on professional grounds, and it applies clear rules for decision making, geared at impartiality, openness, and accountability. For such objectives to be accomplished, moreover, the administration needs to enjoy a high degree of autonomy. Political actors should content themselves with imparting an overall direction to the administrative activities in question; they should not intervene in the process of recruitment or the handling of specific cases (Heredia and Schneider 2003). For Weber, as for many of his successors, it was virtually self-evident that administrative bodies organized on such a basis are more efficient (Breiner 1996). More gets done; a greater number of measures of an appropriate kind are undertaken for each tax dollar. Given the patrimonial 4 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS bureaucracy that formed his frame of reference, this must be regarded as a reasonable assumption.3 Yet, the Weberian type of bureaucracy also can be seen, in turn, as less efficient than one might wish. Its emphasis on formal merits and strict procedures has a price. Objections of just this kind have tended to be raised by champions of the so-called New Public Management School, which takes its frame of reference above all from private business (Osborne and Gaebler 1992). Such superior efficiency may more reasonably be viewed, however, as a matter of administrative standards to be reached in a stepwise fashion. Step one is to leave the patrimonial stage behind; it is then, first, that a bureaucracy in the modern sense has been created. On such a basis—with an organization of administrative operators who have been recruited on rational grounds and who work in a rational way—subsequent steps in an efficiency-enhancing direction could be taken. However, introducing managerial ways of working into a basically patrimonial apparatus would not provide any happy remedy (Heredia and Schneider 2003). All functioning administrations—and thus all well-functioning states—need to be founded on a Weberian basic structure of rational recruitment and standards of procedure. The question we address here is how this capacity is affected by political democratization. Weber himself was aware that there could be risks, since political parties—the primary actors of democracy—are to a great extent driven by patronage interests (which could make them inclined to invade the bureaucracy and exploit it for rent-seeking purposes). But he was optimistic all the same. The principles of clear and impartial rules, which infuse the democratic procedures, coincide nicely with the principles of a rational bureaucracy. The parties would benefit, moreover, from the existence of an efficiently functioning state apparatus: The implementation of their programs, after all, would depend upon it (Breiner 1996; Weber 1994). Measurements of Administrative Capacity When we want to measure the administrative capacity of different states, several types of data could be consulted. The data most frequently used are those furnished by the World Bank, by Transparency International (TI), and by the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). Our study is based on the ICRG data. These have several advantages. First, some of the measurements are substantively relevant. Second, they provide a wide country coverage. Third, comparable data are available for a relatively long period—annually from 1984 onward—thus facilitating a dynamic analysis. The World Bank, too, provides several measurements that are substantively relevant and that provide a wide country coverage. The period covered, though, is relatively short: every other year from 1996 onward. In addition, the ratings presented do not involve absolute measurements of administrative performance in various respects; rather, they furnish rankorderings (i.e., data on an ordinal-scale level) that have been normally dis- DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 5 tributed. It is impossible, therefore, to carry out over-time comparisons with these data. TI, for its part, focuses on corruption, providing yearly measurements in that area for a number of countries. For us, the incidence of corruption is a relevant question, but it is not the only one about which we wish to have information. Other limitations concern the period for which the data were collected and the fairly narrow country coverage. Among the ratings done by the ICRG (2005), we make use of two. The first is clearly relevant for our purposes: It measures “Bureaucracy Quality,” which is a general assessment of the performance of the administrative apparatus. The second is “Control of Corruption.” As we see it, the incidence of corruption can be seen as an indirect measurement of the quality of administration. Corrupt decision making is an indication that rules of administrative procedures of equal treatment, openness, and control are not being upheld. Corruption also, as a rule, brings with it a misallocation of public resources, thus reducing efficiency (Della Porta and Vannucci 1997; World Bank 1997).4 These two measures are strongly correlated (Pearson’s r for the whole period is 0.69, significant at the 0.01 level). The two indicators are combined into an additive index of administrative capacity. Relationship between Democracy and Administrative Capacity over Time As is well known, democracy has made substantial advances in the world over recent decades. The global trend has been steadily upward and has encompassed a majority of regions. The striking exception is the Middle East and North Africa. Overall, that region has seen no change: The average level of democracy is as low at the start of the new millennium as it was 30 years ago. Nor is there anything to indicate that this general pattern will be changing in the near future. Factors such as Muslim religion and oil resources are clearly negative for democracy’s part. Traditional monarchies, moreover—of which there are many in the area—have shown themselves unusually resistant to change (Hadenius and Teorell 2007). Questions related to state capacity, like democracy, have attracted considerable attention in the field of international cooperation, especially after the Cold War. Far-reaching efforts have been made to improve conditions (see, e.g., World Bank 1994, 1997). One might have thought, then, that the trend of development on the global level in regard to administrative capacity would be as clearly upward as it has been in regard to democracy. Yet this has not been the case, according to the available data from the ICRG. Democracy has advanced, but the level of administrative capacity has fallen (see Figure 1a). The tendency further holds for virtually every region (Figure 1b). 6 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS FIGURE 1 A. Democracy and Administrative Capacity over Two Decades (All Countries) and B. Democracy and Administrative Capacity over Two Decades across Regions 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 a 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 year Average level of democracy Average level of adm. capacity b Latin America Middle East, North Africa Western Europe, North America Asia 0 5 10 Eastern Europe, Central Asia 0 5 10 Sub-Saharan Africa 1985 1990 1995 2000 1985 1990 1995 2000 1985 1990 1995 2000 Year Average level of democracy Average level of adm. capacity Graphs by World region Note: Democracy is measured as the average value of Polity and Freedom house. Administrative capacity is the average value of two ICRG indicators, corruption and bureaucratic quality. ICRG, International Country Risk Guide. DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 7 Here too, however, there is a single clear exception: the Middle East and North Africa. In that part of the world, the level of administrative capacity has been quite stable throughout the period. We also notice another pattern: These countries do substantially better in the area of administrative capacity than in that of democracy. The converse pattern obtains in Latin America, where substantial democratic advances have occurred. But when it comes to administrative capacity the level is still quite low: There is a striking gap between the two curves. Several of these graphs indicate a negative correlation between democratization and administrative capacity. The Middle East/North Africa, a region with a stable authoritarian pattern, displays a level of administrative capacity that rates rather well in an international perspective; while Latin America, a region that has seen far-reaching democratic advances since the end of the 1970s, is a clear underachiever in terms of administrative capacity. In Africa and in Eastern Europe/Central Asia; moreover, the two curves clearly cross each other during the period: Democracy goes up while the level of administrative capacity goes down. It is the actual incidence of such a negative relationship that, with the help of multivariate analyses, we explore in this article. Previous Cross-Country Research Several researchers have evaluated the relationship between democracy and corruption in a cross-national context. Some have found no effect (see, e.g., Paldam 2002; Sandholtz and Koetzle 2000). Others have found a weak, but significant, effect of democracy, at least when the number of consecutive years a country has been fully democratic is accounted for (see, e.g., Blake and Martin 2006; Bohara, Mitchell, and Mittendorff 2004; Gerring and Thacker 2004; Treisman 2000). However, these researchers have only studied the linear effects of democracy on corruption. Only two articles, by Montinola and Jackman (2002) and Sung (2004), investigate whether the relationship could be curvilinear in character. Montinola and Jackman (2002) use data from Business International (BI) in the early 1980s to measure corruption levels across 66 countries. To test the curvilinearity of the democracy–corruption relationship, a squared democracy variable is included in the regression. They conclude that the effect of democracy is nonlinear and that some authoritarian regimes actually experience lower levels of corruption than countries at intermediate levels of democracy. Sung (2004) studies corruption using TI data across 103 countries over six years (1995–2000). To evaluate the shape of the relationship between democracy and corruption, three statistical equations are used: a linear, a quadratic, and a cubic. The author concludes that democracy decreases corruption; yet, temporary upsurges in government corruption are to be expected during the early stages of the process of liberalization. 8 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS None of these studies that have looked at curvilinear effects have been based on time-series cross-sectional data. Hence, the democracy– corruption relationship has not been studied dynamically.5 Drawing on such studies, it is not possible to determine the direction of causality. All that can be substantiated is the existence of a static relationship. To remedy this problem, we base our study on data that varies over about two decades and involves evident changes in many regions of the world, both with respect to democracy and administrative capacity. Data and Method The ICRG data described above enable us to measure administrative capacity in about 140 countries over 19 years. As for the two indicators used, Corruption and Bureaucratic Quality, the first taps the actual or potential corruption in the form of excessive patronage, nepotism, job reservations, secret party funding, and so on. The other item measures the strength and the quality of the bureaucracy, defined as its “ability to govern without drastic changes in policy or interruptions in government services” (ICRG Codebook). These indicators have been rescaled to vary between zero and 10, and have been aggregated into an additive index. To measure democracy, we make an average of the yearly Freedom House (Political Rights) and Polity scores, and standardize this measure to vary between zero and 10, giving us the democracy level for 193 countries over a period from 1970 to 2003.6 In order to gauge the potential curvilinear nature of the relationship, we incorporate a squared version of the democracy variable in our regressions. After taking missing data into account, our data set includes about 125 countries, with annual observations from 1984 to 2002, resulting in about 2,000 cases. In order to avoid potential omitted variable bias, we include three control variables, which are all features that may affect both the level of democracy and the administrative capacity of a country. Several authors have claimed that a country’s level of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita could affect its level of democratization (see, e.g., Hadenius and Teorell 2005a; Przeworski et al. 2000). Most researchers trying to explain corruption also include GDP per capita as a predictor (see, e.g., Lederman, Loayza, and Reis Soares 2001; Montinola and Jackman 2002; Treisman 2000). We here take the natural logarithm of GDP per capita in constant 1995 U.S. dollars.7 Researchers interested in testing the dependency theory often include a variable measuring the openness of trade as a predictor of democratization (see, e.g., Hadenius and Teorell 2005a; Li and Reuveny 2003), and this feature is also expected to influence the costs and benefits of engaging in corrupt activities (see, e.g., Bohara, Mitchell, and Mittendorff 2004; Lederman, Loayza, and Reis Soares 2001).8 In this study we measure trade openness as the sum of exports and imports of goods and services expressed as their share of the GDP.9 Several authors have argued that British colonialism is more favorable to democratization than DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 9 other types of colonial heritage (see, e.g., Bernard, Reenock, and Nordstrom 2004; Hadenius and Teorell 2005a), and it has also been argued that British colonial heritage should lower corruption, the point being that the British passed on to their colonies a legal culture that emphasized a norm of compliance with the principles of rule-governance (e.g. Sandholtz and Koetzle 2000; Treisman 2000). Thus, we include a measure indicating whether or not a country is a former British colony. A Time-Series Cross-Section Model As argued above, the relationship between democracy and governance should not only be studied across countries, but also over time, that is, dynamically. This means we are dealing with time-series cross-section (TSCS) data. Beck and Katz have discussed issues related to using TSCS data in a series of articles (see, e.g., Beck and Katz 1995, 1996, 2004). We will follow their advice and use ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with panel corrected standard errors. Beck and Katz (1995, 634) argue that OLS estimates of TSCS model parameters are not optimal, but they “often perform well in practical research situations.” OLS standard errors, which determine the significance of our estimates, should however not be used, since they are likely to be inaccurate because errors in TSCS models are often plagued by contemporaneous correlation and heteroscedasticity. Beck and Katz (1995) provide a procedure for correcting the OLS standard errors, which is used here. In order to avoid potential endogeneity problems, we lag all independent variables by one year. This means that the independent variables are measured at t – 1, whereas the dependent variable, that is, administrative capacity, is measured at t. We also include the lagged dependent variable in some regressions, that is, we include a variable measuring administrative capacity at t – 1. As described by Teorell and Hadenius (2007), there are several reasons for including the lagged dependent variable. For one thing, this helps to control for serial correlation in the error terms. Also, the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable helps to control for potential endogeneity bias, since this makes sure that any effects on Yi of xi “occurring previous to t – p is controlled for,” where p is the number of years that Y is lagged (see also Beck and Katz 1996; Hadenius and Teorell 2005a). Finally, we also run all regressions including country fixed effects. To this end, we add a dummy for each country on the right-hand side of the regression. In this type of analysis, time-invariant variables are excluded, since the inclusion of fixed country effects means that we are only studying the variation across time; that is, we are no longer studying the variation across countries. As described by Persson and Tabellini (2003, 45), the “fixed-effect specification has the advantage of holding constant any unobserved (omitted) country-specific (time-invariant) determinants” of the dependent variable.10 10 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS Empirical Findings A Curvilinear Relationship between Democracy and Administrative Capacity We start out by presenting a scatterplot describing the variation in democracy and administrative capacity across countries in 2002, presented in Figure 2. This plot suggests that that the two traits are associated in a curvilinear manner. Countries such as Saudi Arabia (SAU) and Cuba (CUB) score very low on the democracy scale (0.5–1), but display a fairly high administrative capacity (about 4), whereas other countries, such as Liberia (LBR) and Haiti (HTI), with slightly higher democracy levels (3–4), feature a very low administrative performance (1–2). The highest levels in both regards are for the most part found not only in Western Europe (e.g., Finland (FIN) and the Netherlands (NLD)), but also in New Zealand (NZL). An extreme outlier is the case of Singapore (SGP), with a relatively low democracy score (4.08) and a high administrative score (8.75). Table 1 contains two types of regression analyses, where the first three columns (models 1–3) present the results from the pooled time-series 10 FIGURE 2 Democracy and Administrative Capacity in 2002 FIN NZL NLD Administrative capacity (ICRG) 2 8 4 6 SGP CUB SAU LBR 0 HTI 0 2 4 6 Democracy (FH/Polity) 8 10 ICRG, International Country Risk Guide; FH, Freedom House; FIN, Finland; NZL, New Zealand; NLD, the Netherlands; SGP, Singapore; CUB, Cuba; SAU, Saudi Arabia; LBR, Liberia; HT, Haiti. 2,115 127 0.589 – 0.938*** (0.024) -0.032 (0.077) 0.433*** (0.045) 0.148*** (0.013) – 2,115 127 0.622 – 0.731*** (0.030) -0.025 (0.072) 0.438*** (0.030) -0.555*** (0.049) 0.069*** (0.005) (2) 0.927*** (0.020) 1,998 127 0.963 0.040** (0.019) -0.020 (0.032) 0.072*** (0.024) -0.055*** (0.020) 0.007*** (0.002) (3) 2,115 127 0.576 – 0.469*** (0.149) 0.275* (0.153) – 0.063*** (0.015) – (4) 2,115 127 0.605 – 0.276* (0.151) 0.298* (0.152) – -0.250*** (0.056) 0.033*** (0.006) (5) Administrative Capacity Fixed Effects Regression 0.885*** (0.011) 1,998 127 0.940 -0.248*** (0.078) 0.004 (0.076) – -0.083*** (0.028) 0.009*** (0.003) (6) Notes: Significant at *the 0.10 level, **the 0.05 level, and ***the 0.01 level. Entries are unstandardized regression coefficients with panel corrected standard errors in parentheses (obtained using STATA:s xtpcse command). GDP, gross domestic product. Number of observations Number of countries Adjusted/overall R2 Lagged dependent variable Administrative capacity at t - 1 British colony Trade openness Control variables Log GDP/capita Democracy2 Democracy variables Democracy (1) Administrative Capacity Pooled Time-Series Cross-Section TABLE 1 Democracy and Administrative Capacity (Regression Analyses) DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 11 12 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS cross-section analyses, and where the last three columns (4–6) present the results from the country fixed-effects analyses. In model 1 we include our democracy measure and the three control variables, GDP, trade openness, and British colony. All variables, except trade openness, exert significant effects in the expected direction. Thus, administrative capacity is higher the higher the level of democracy and GDP per capita and in former British colonies. In model 2 we add the squared democracy variable in order to gauge the existence of a curvilinear relationship. In this model, the democracy variable exerts a significant negative effect on administrative capacity, and the squared democracy variable exerts a significant positive effect. The inclusion of the latter variable also increases the adjusted R2 by three percentage points. In all, the outcome of this regression attests to the curvilinear character of the relationship; it holds, as we can see, under control for other explanatory conditions of importance. In model 3, we add the lagged dependent variable to our model. In this model, thus, we control for administrative capacity at t – 1. The coefficients for our democracy variables are clearly smaller in this model, but remain statistically significant. In models 4 to 6 we present the results from regressions with country fixed effects. In these specifications, accordingly, only the variation across time is taken into account. For the democracy variables, the results are quite similar to the results found in the pooled TSCS analysis. This adds to the robustness of our findings. In order to find out at what point democracy has a negative effect and at what point it has a positive effect on administrative performance, we have calculated the predicted effects at different values of the democracy variable, presented in Table 2. When the level of democracy is 0, the predicted effect of democracy on the administrative score is –0.055. This negative effect is significant at the 0.01 level, suggesting that a democratization of countries that are extremely authoritarian will lower the administrative quality. Looking at countries that are somewhat democratized, with democracy scores between three and four, the effect of further democratization does not significantly affect administrative capacity, whereas countries with democracy scores higher than five are expected to experience an improvement in the administrative capacity when they are further democratized. At these democracy scores, namely, the effect of democracy is positive and significant. Figure 3 illustrates the shape of the curve. The democracy measure has here been plotted against the predicted values from a model including democracy and democracy squared as predictors of administrative capacity. The relationship is clearly J-shaped, with a negative effect of democracy at low levels of democracy and a positive effect at fairly high democracy levels. A way to picture the fit of our regression model is to graph actual levels of administrative performance against the predicted values. In Figure 4, DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 13 TABLE 2 Predicted Effects on Administrative Capacity at Different Levels of Democracy Level of Democracy 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Predicted Effect -0.055*** (0.020) -0.042** (0.017) -0.029** (0.013) -0.016 (0.010) -0.002 (0.008) 0.011 (0.007) 0.024*** (0.008) 0.037*** (0.011) 0.050*** (0.014) 0.063*** (0.018) 0.076*** (0.022) 95% Confidence Interval –0.095 to –0.015 -0.074 to -0.009 -0.054 to -0.003 -0.035 to 0.004 -0.017 to 0.012 -0.003 to 0.024 0.007 to 0.040 0.015 to 0.059 0.022 to 0.078 0.028 to 0.099 0.034 to 0.119 Notes: Significant at **the 0.05 level, ***the 0.01 level. The predictions are made using STATA:s nlcom command after the regression of model 3, including democracy, democracy2, GDP per capita, trade openness, British colony, and the lagged dependent variable. Standard errors in parentheses. GDP, gross domestic product. we plot the predictions from model 2 for 2002. Figure 4 illustrates that the fit of this model is fairly good, with countries lining up on the diagonal.11 Thus, countries that our model predicts will perform well also do so. There are, however, exceptions to the rule. Some countries, like Italy (ITA), display a lower administrative score than would be expected according to their level of democracy and GDP per capita, and other countries, like Singapore (SGP), have higher administrative scores, than would be expected from their democratic and economic situation. Two Methods of Steering and Control Thus, a curvilinear relationship obtains between democratization and administrative capacity. As we see it, the curvilinear relationship results from the combined effect of two forms of steering and control that can be applied in public life. One is exercised from above, the other from below. 14 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS 3 Predicted level of administrative capacity 4 6 5 7 8 FIGURE 3 Democracy and Predicted Level of Administrative Capacity 0 2 4 6 Level of democracy 8 10 For efficient steering and control from above, the following instruments are needed: 1. centralized policy making, 2. centralized resources, 3. top-down modes of implementation, and 4. statutory organs of control. The direction and subsequent review of the public apparatus is easier if the more important policy decisions, together with their follow-up, are centralized to a single main arena. Coordination is enhanced and decision costs reduced thereby. Centralization, in turn, is facilitated if critical resources are controlled within one and the same decision making arena. This is particularly true with respect to tax revenues and the earnings from business activities in which the state is involved. In addition, the model involves top-down modes of implementation. Such an order is hierarchical: Powers of initiative and procedures for reporting to superiors are laid down from above. Alongside an internal administrative control in a variety of areas, there are special central agencies, such as auditing agencies, charged with the review of operations from without. DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 15 Predicted level of administrative capacity 4 6 8 2 10 FIGURE 4 Predicted versus Actual Values of Administrative Capacity in 2002 ITA SGP 0 2 4 6 8 Actual level of administrative capacity 10 In all functioning states, instruments for steering and control from above are prominently present. If there were no such instruments, there would be no functioning state. State-ness presumes a substantial centralization of public activities. In the matter of state-ness there is, one might say, a zero-sum game: The central state institutions either exercise sovereignty within their geographical territory, or they do not. Sovereign state organs possess a basic capacity of supremacy, that is, they are able to hold competing power centers at bay (Krasner 1999). Yet, the means that make state-ness possible are not always those that promote administrative capacity. As critics of the centralized model have noted, such a model has serious drawbacks at times—especially when it comes to the implementation and follow-up of various public measures. It is not always easy to get the arm of the state to reach out and to produce the intended effect in the field. The difficulty consists in being able (1) to adapt the measures taken to the conditions prevailing in different places and (2) to gather sufficient feedback on how the measures in question have actually worked. In other words, there is both an adaptation problem and an information problem. The cooperation of various actors in society can help to ease difficulties of this kind (Fox 2004; Ostrom 1990). It is such cooperation on the part of those affected that is the essence of what we here call steering and control from below. This form of direction and review is facilitated by the use of the following instruments: 16 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS 1. divided/decentralized policy making, 2. divided/decentralized resources, 3. implementation through cooperation, and 4. public review, through transparency and public participation. Cooperation on the part of the social groups affected is easier if the public apparatus is divided both vertically and horizontally—so that decentralization and checks and balances characterize every level. Opportunities for access and for public oversight are increased thereby. But for such things to be achieved, control over critical resources must be dispersed in a similar fashion. Furthermore, implementation must be accomplished to a great extent through cooperation with the groups most heavily affected. It is a matter of working out appropriate measures through dialogue and of inducing those affected to participate as partners in the practical implementation of said measures. This can make policy adaptation easier. The object, furthermore, is to involve different groups of citizens in the process of review and assessment: to get them to work as inspectors and whistle-blowers. The advantage of such an arrangement is that those who are close to the operations of a given public program tend to have a good sense of how well it has worked. This “social auditing” can take many different forms. At a general level, the aim is to create arenas and channels wherein popular reactions to public programs can come to expression. Such involvement by the stakeholders could make up for the well-known inability on the part of central organs to effectively direct and review public activities out in the field (Ackerman 2003; Fukuyama 2004; Tendler 1997). Such direction and review cannot replace the top-down kind; rather, it furnishes a complement. In the best case a synergy between the two forms can be created: The direction is applied in dialogue and cooperation, while the more professional type of statutory auditing is combined with a more popular and social form. It is when an interaction of this kind can be created that the highest level of administrative capacity can be reached. Thus, interaction between state and society is to the benefit of both (Evans 2005; Hadenius 2003; Lange 2005; Wang 1999). In contrast to the case with basal state-ness, we here have a positive-sum game: The state’s bureaucratic capacity can be enhanced if other actors in society are invited to take part in directing and reviewing the actions of the administrative apparatus. Such positive interaction between state and society can only be created, as a rule, in certain institutionally and organizationally developed democracies. These states not only have well-institutionalized organs for steering and control from above, but they are also able to make use of functioning channels for societal participation in the policy process (Hadenius 2001). It is for this reason the administrative capacity is highest among developed democracies. The establishing of well-functioning democratic institutions DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 17 could involve several advantages with respect to administrative performance. Factors like political competition and freedom of assembly and the press further transparency and accountability. This makes it easier to detect and to actively combat abuses in the public agencies. At the opposite end—in an authoritarian setting—a satisfactory measure of direction and review from above can at times be accomplished, especially if the state is able to draw on a flourishing resource base and to take harsh measures against low performance. Such advantages can make up, to a great extent, for the meager measure found in such societies of steering and control from below. The monarchies of the Middle East would seem to be successful examples hereof. With access to vast and highly profitable natural resources, these states have been able to establish not just a large-scale repressive apparatus, but a fairly well-functioning bureaucratic system as well (Bellin 2004; Herb 1999; Ross 2001). The administrative performance of these states does not reach top-notch level, but it stands out as relatively good in comparative perspective. When authoritarian structures are relaxed, however, administrative capacity tends to decline. The reason for the downturn is that centralized forms of management, which could be used before, are not so easily maintained when the system is loosened up. Changes of the latter sort normally involve, after all, the appearance of numerous new actors on the scene, making control more difficult. At the same time, the most brutal forms of retribution can no longer be employed, weakening the forceful arm of the state. But this weakness is not made up for—at least not to a sufficient extent—by the development of institutions and social networks able to serve as vehicles for steering and review from below. At this stage, accordingly, none of the instruments that can do the job are present in a satisfactory degree. When a state has just begun its democratization, then many of the institutional requisites for democracy are still lacking. Competition between parties, for example, is still highly restricted as a rule. The governing side may still be greatly favored in respect of economic and organizational resources, and it may yet be able to influence the electoral process to its own advantage. Freedom of assembly and of the press may also be highly restricted. At this stage, the effects conducive to state capacity that democratization can yield do not appear. The administrative capacity accordingly falls. As can be seen in Figure 3, it reaches its lowest point at about level 4 on the scale of democracy. After that it moves sharply upward. It is first when the level of democracy is between 7 and 8, however, that we find an administrative quality clearly exceeding that of the strongly authoritarian states. It is a level of around 7.5 that is often taken as the categorical boundary between democracy and its absence (Hadenius and Teorell 2005b). It is first above this level, among the full-fledged democracies, that the real profits of democratization appear. From about the middle of the scale, then, higher levels of democracy bring gradually with them a higher administrative quality. But it is first 18 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS when a high level of democracy has been attained that such political changes tend to bring their reward in the administrative realm. However, even relatively well-established democracies sometimes display a mediocre and sometimes declining administrative performance. This is true to a great extent in Latin America (Argentina and Brazil are striking examples). Such differences in performance reflect differences in the quality of democracy above and beyond its purely institutional requisites. To function properly, democratic institutions must not only be accompanied by a broad array of political resources in society, such as individual resources relating to knowledge and political activation, but also collective resources, such as the development of a vital press, and of well-rooted parties and organizations, able to operate as tools of communication and representation. In many countries that have undergone democratization, the development of such features has been uneven.12 Thus, we suspect that the picture becomes clearer if we consider not only the development of democratic institutions, but also the development of various political resources. In Table 3 we present some analyses aimed at evaluating the proposed explanations of the curvilinear relationship documented above. In model 1 we present a base model, including the democracy variables and some control variables.13 In the following model we also include a measure of political activity, namely, electoral participation, using data provided by Vanhanen (2000). This of course is a less than perfect measure of political activity, since it is restricted to electoral activity and thus excludes other forms of political participation. Yet, this is the only measure that could provide a reasonable cross-country and cross-time coverage. In this model we also add a variable tapping the daily circulation of newspapers per capita, drawing on Banks (1995).14 The newspaper circulation variable exerts a positive and significant effect in model 2, suggesting that countries with a high level of circulation of newspapers also are marked by higher administrative scores. This could be due to the fact that it is easier to oust bad officeholders in such countries, since the public becomes more aware of bad administrative practices through their media usage. The effect of the electoral participation variable is positive as expected, but not significant. At the same time, in model 2, the two democracy variables still hold their own; the coefficients are only slightly reduced when the resource variables are introduced. This implies that the effect of the resource variables could only be complementary to the effect of the democratic institutions. To further evaluate this effect, we have constructed a variable that represents the interaction between newspaper circulation and the level of democracy. The idea is that the relationship between democracy and governance is conditional: When democracy is associated with the presence of certain capacities in society, this adds to the quality of administrative practices. More concretely, democratization should have a greater impact when there are favorable media conditions, enabling the citizenry to 0.666*** (0.037) 0.506*** (0.026) 1912 124 0.619 0.001 (0.002) 0.274*** (0.030) – -0.422*** (0.051) 0.053*** (0.004) (2) 0.768*** (0.031) 0.603*** (0.031) 1912 124 0.634 0.005** (0.002) –0.625*** (0.090) 0.104*** (0.009) -0.272*** (0.047) 0.029*** (0.004) (3) 1.126*** (0.057) 0.670*** (0.044) 1240 105 0.660 – – – 0.178*** (0.031) – (4) 0.885*** (0.047) 0.805*** (0.041) 1240 105 0.678 0.006** (0.003) 0.326*** (0.027) – 0.160*** (0.026) – (5) Adm. Capacity (TSCS) Only Democracies Notes: Significant at **the 0.05 level, ***the 0.01 level. Entries are unstandardized regression coefficients with panel corrected standard errors in parentheses. GDP, gross domestic product; TSCS, time-series cross-section. Number of observations Number of countries Adjusted R2 British colony 0.800*** (0.036) 0.436*** (0.016) 1912 124 0.609 – Newspaper circulation ¥ democracy Control variables Log GDP/capita – – -0.458*** (0.055) 0.059*** (0.005) Newspaper circulation Intervening variables Turnout Democracy2 Democracy variables Democracy (1) Administrative Capacity (TSCS Data)All Observations TABLE 3 Democracy and Administrative Capacity—Explaining Curvilinearity (Regression Analyses) DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 19 20 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS obtain sufficient information about the public activities, and to hold the persons in charge accountable. As can be seen in Table 3, the combined democracy/newspaper circulation variable has an evident individual impact. What is telling, moreover, is the effect on the two democracy variables. For both of them, the coefficients are reduced considerably. This implies that the influence of democracy on administrative performance is due to an important degree to an interaction between democratization and improvements in the field of newspaper circulation. In the remaining models (4–5) we concentrate on the upturn-side of the J-curve. As it is here a matter of a mainly linear relationship between democracy and governance, we only apply the original democracy variable. Moreover, only observations higher than four on the democracy index become relevant in this analysis.15 Using this sample, we present a new base model (4). In model 5 we add the intervening variables. In this test the variables measuring electoral participation and newspaper circulation both exert significant effects, suggesting that countries that have a high level of electoral participation and a high level of newspaper circulation perform better administratively. As before, the democracy variable is strongly significant, while the coefficient is slightly reduced. This illustrates, again, that there is no clear-cut trade-off between democracy development and resource development. For administrative improvement, these features should be developed in conjunction. Conclusion The question addressed in this article is the following: Does democratization affect the state’s administrative capacity—and if so, in what way? Previous efforts to give an answer to this question have given fairly inconclusive results. That is due to two deficiencies, which have marked earlier studies in the field. One relates to the object of investigation. Previous researchers have concentrated on the effects of democracy on one particular aspect of administrative performance: the incidence of corruption. The other, more fundamental deficiency is methodological in nature. Previous research has been based only on cross-sectional analyses, which could only give a static portrayal of the relationship. To say something about the dynamic effects, time-series data need to be utilized. Our study is the first to apply a more composed measure of administrative capacity and of addressing the democracy–administrative capacity relationship by the use of time-series data. Our results point to the existence of a curvilinear—J-shaped— relationship between democracy and administrative performance. Democratization of a highly authoritarian country leads to a reduction in the administrative capacity, whereas further democratization of a semi-authoritarian country does not yield any effect on this capacity. However, in more democratic countries, further democratization tends to DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 21 have a positive, and increasingly significant, effect on the state’s administrative capacity. We propose that the curvilinear relationship could be better understood in view of two forms of steering and control that can be applied, one from above and another from below. The fact that administrative performance decreases when an authoritarian country is democratized could be explained by the fact that the ability of the state to perform successful steering from above is weakened when old structures of power concentration and repression are loosened up. Before the development of more full-fledged democratic institutions—which are combined with the development of essential political resources in society—the necessary conditions for effective steering and control from below are still wanting. Hence, at an intermediary stage of democratization, no improvements on the administrative side are accomplished. In consequence, administrative performance stays at a low point. It is only at higher levels of democracy, and when such advancement is followed by the evolution of political resources, that the positive effects in the administrative realm are realized. We evaluate this argument by introducing two measures of political resources in society: electoral turnout and press circulation. Our results generally support the proposed argument. Besides the effect of democracy itself, the emergence of resources count. We conclude that the best breeding ground for administrative improvement is the simultaneous establishment of democratic institutions and the development of vital political societal resources. Sometimes, however, such parallel development is not achieved; the basic institutions are put in place, but no equivalent improvements take place in the realm of societal resources. This, in our understanding, is the key to the particular administrative underperformance that marks the region of Latin America. Notes 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. By “states,” in a juridical sense, we mean those that are internationally recognized by the UN and by other states. In certain cases, however, this capacity in terms of international recognition is not matched by any domestic capacity in terms of state-ness (Jackson and Rosberg 1982; Krasner 1999). This distinction between basal state-ness and bureaucratic capacity is very clear in Weber (1994) and Breiner (1996). In later research, however, these two capacities have sometimes been confounded (e.g., Migdal 1988; Nettle 1968). Not many studies, based on systematic empirical evidence, have been made in this field. One exception is Putnam’s (1993) study of the quality of governance of the regions of Italy. Another ICRG measurement is “Law and Order.” The degree to which the rule of law is respected indeed lies close to our focus. The problem here has to do with “Order,” which registers illegal protests. In a more or less authoritarian context, popular protests may indicate a weak political legitimacy. Some authors have studied the relationship between political variables and corruption across time (see, e.g., Lederman, Loayza, and Reis Soares 2001; 22 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Persson, Tabellini, and Trebbi 2003), but they have not investigated the curvilinear nature of this relationship. The Polity index has a lower country coverage than the Freedom House index and therefore we have replaced some missing values with the imputed value for Polity (using the Political Rights index as a predictor of Polity). Source: World Development Index, World Bank National Accounts data, and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development National Accounts data files. See Bohara, Mitchell, and Mittendorff (2004) for a number of arguments why trade openness should reduce corruption. Source: see footnote 7. As argued by Beck and Katz (2004, 5), omitting fixed effects when they are needed can create severe omitted variable bias. The problem is that fixed effects “makes it difficult for variables that change only slowly to show their impact (when their impact is by and large inter- and not intra-unit).” We exclude the trade variable because it contains some missing values. See, for example, Stokes (2001) and Altman and Pérez-Liñán (2002). As we are here only interested in studying how much the effect of the democracy variable is reduced when some variables are added, we exclude the lagged dependent variable. This variable has been rescaled by dividing it by 1,000. The rationale for only including the democracy variable is that we are now focusing on explaining the positive effect of democracy among the more democratic observations. We chose the cut point 4 because it is only at democracy scores above 4 that the effect of democracy is positive (the effect is positive at a democracy level of 4.2 and above, and the effect is positive and significant from 5.1). References Ackerman, John. 2003. “Co-Governance for Accountability: Beyond ‘Exit’ and ‘Voice.’” World Development 32: 447–463. Altman, David, and Aníbal Pérez-Liñán. 2002. “Assessing the Quality of Democracy: Freedom, Competitiveness and Participation in Eighteen Latin American Countries.” Democratization 9: 85–100. Banks, Arthur. 1995. Political Handbook of the World 1994–1995. Birmingham: CSA Publications. Beck, Nathaniel, and Jonathan Katz. 1995. “What to Do (and Not to Do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data.” The American Political Science Review 89: 634– 647. ———. 1996. “Nuisance vs. Substance: Specifying and Estimating Time-Series Cross-Section Models.” Political Analysis 6: 1–36. ———. 2004. “Time-Series–Cross-Section Issues: Dynamics, 2004.” Working Paper, The Society of Political Methodology. Bellin, Eva. 2004. “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Exceptionalism in Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Politics 36: 139–157. Bernard, Michael, Christopher Reenock, and Timothy Nordstrom. 2004. “The Legacy of Western Overseas Colonialism on Democratic Survival.” International Studies Quarterly 48: 225–250. Blake, Charles H., and Christopher G. Martin. 2006. “The Dynamics of Political Corruption: Re-Examining the Influence of Democracy.” Democratization 13: 1–14. Bohara, Alok K., Neil J. Mitchell, and Carl F. Mittendorff. 2004. “Compound Democracy and the Control of Corruption: A Cross-Country Investigation.” The Policy Studies Journal 32: 481–499. DEMOCRACY AND STATE CAPACITY 23 Breiner, Peter. 1996. Max Weber and Democratic Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Della Porta, Donatella, and Alberto Vannucci. 1997. “The ‘Perverse Effects’ of Political Corruption.” Political Studies 45: 516–538. Evans, Peter. 2005. “Harnessing the State. Strategies for Monitoring and Motivation.” In States and Development. Historical Antecedents of Stagnation and Advance, ed. Lange Matthew and Dietrich Rueschemeyer. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Fox, Jonathan. 2004. “Empowerment and Institutional Change: Mapping ‘Virtuous Circles’ of State–Society Interaction.” In Power, Rights, and Poverty: Concepts and Connections, ed. Ruth Alsop. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Fukuyama, Frances. 2004. State Building. Governance and World Order in the TwentyFirst Century. London: Profile Books. Gerring, John, and Strom C. Thacker. 2004. “Political Institutions and Corruption: The Role of Unitarism and Parliamentarism.” British Journal of Political Science 34: 295–330. Hadenius, Axel. 2001. Institutions and Democratic Citizenship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ———, ed. 2003. Decentralization and Democratic Governance. Experiences from India, Bolivia and South Africa. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. Hadenius, Axel, and Jan Teorell. 2005a. “Cultural and Economic Prerequisites of Democracy: Reassessing Recent Evidence.” Studies in Comparative International Development 39: 87–106. ———. 2005b. “Assessing Alternative Indices of Democracy”. C&M Working Papers, IPSA. ———. 2007. “Authoritarian Regimes: Stability, Change, and Pathways to Democracy, 1972–2003.” Journal of Democracy 18: 143–158. Herb, Michael. 1999. All in the Family. Absolutism, Revolution, and Democracy in the Middle Eastern Monarchies. New York: State University of New York Press. Heredia, Blanca, and Ben Ross Schneider. 2003. “The Political Economy of Administrative Reform in Developing Countries.” In Reinventing Leviathan. The Politics of Administrative Reform in Developing Countries, ed. Ben Ross Schneider and Blanca Heredia. Coral Gables, FL: North-South Press Center. International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). 2005. A Business Guide to Political Risk for International Decisions. New York: The PRS Group. Jackson, Robert, and Carl Rosberg. 1982. “Sovereignty and Underdevelopment Juridical Statehood in the African Crisis.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 24: 1–31. Krasner, Stephen. 1999. Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Lange, Matthew. 2005. “The Rule of Law and Development: A Weberian Framework of States and State–Society Relations.” In States and Development. Historical Antecedents of Stagnation and Advance, ed. Lange Matthew and Dietrich Rueschemeyer. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Lederman, Daniel, Norman Loayza, and Rodrigo Reis Soares. 2001. “Accountability and Corruption. Political Institutions Matter.” Policy Research Working Paper, 2708. Washington DC: The World Bank. Li, Quan, and Rafael Reuveny. 2003. “Economic Globalization and Democracy: An Empirical Analysis.” British Journal of Political Science 33: 29–54. Mann, Michael. 1986. “The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins, Mechanisms and Results.” In States in History, ed. John Hall. New York: Basil Blackwell. Migdal, Joel. 1988. Strong Societies and Weak States. State–Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Montinola, Gabriella R., and Robert W. Jackman. 2002. “Sources of Corruption: A Cross-Country Study.” British Journal of Political Science 32: 147–170. 24 HANNA BÄCK AND AXEL HADENIUS Nettle, J. P. 1968. “The State as a Conceptual Variable.” World Politics 20: 559–592. Osborne, David, and Ted Gaebler. 1992. Reinventing Government. Reading, MA: Adison-Wesley. Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Paldam, Martin. 2002. “The Cross-Country Pattern of Corruption: Economics, Culture and the Seesaw Dynamics.” European Journal of Political Economy 18: 215–240. Persson, Torsten, and Guido Tabellini. 2003. The Economic Effects of Constitutions. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Persson, Torsten, Guido Tabellini, and Francesco Trebbi. 2003. “Electoral Rules and Corruption.” Journal of the European Economic Association 1: 958–989. Przeworski, Adam, Michael Alvarez, Jose Antonio Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi. 2000. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and WellBeing in the World, 1950–1990. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Putnam, Robert. 1993. Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Ross, Michael. 2001. “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” World Politics 53: 325–361. Sandholtz, Wayne, and William Koetzle. 2000. “Accounting for Corruption: Economic Structure, Democracy and Trade.” International Studies Quarterly 44: 31–50. Stokes, Susan. 2001. Mandates and Democracy: Neoliberalism by Surprise in Latin America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Sung, Hung-En. 2004. “Democracy and Political Corruption: A Cross-National Comparison.” Crime, Law and Social Change 41: 179–194. Tendler, Judith. 1997. Good Governance in the Tropics. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Teorell, Jan, and Axel Hadenius. 2007. “Determinants of Democratization: Taking Stock of the Large-N Evidence.” In Democratization: The State of the Art, ed. Dirk Berg-Schlosser. Farmington Hills, MI: Barbara Budrich. Treisman, Daniel. 2000. “The Causes of Corruption: A Cross-National Study.” Journal of Public Economics 76: 399–457. Vanhanen, Tatu. 2000. “A New Dataset for Measuring Democracy, 1810–1998.” Journal of Peace Research 37: 251–265. Wang, Xu. 1999. “Mutual Empowerment of State and Society: Its Nature, Conditions, Mechanisms, and Limits.” Comparative Politics 31: 231–249. Weber, Max. 1994. Political Writings. ed. Peter Lassman and Ronald Speirs. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. World Bank. 1994. Governance: The World Bank’s Experience. Washington, DC: World Bank. ———. 1997. World Development Report 1997. The State in a Changing World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.