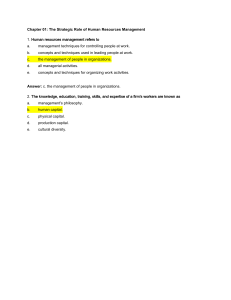

Oper Manag Res (2017) 10:148–157 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-017-0128-1 The impact of mindful organizing on operational performance: An explorative study Hung-Chung Su 1 Received: 14 July 2016 / Revised: 19 October 2017 / Accepted: 31 October 2017 / Published online: 22 November 2017 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2017 Abstract This study explores the effect of Mindful Organizing, a concept originally developed in the highreliability organizations literature. We show that mindful organizing can also be applied to ordinary organizations seeking better performance, not just to organizations seeking high reliability. Results of this study demonstrate that mindful organizing and operational performance are positively related. Further, mindful organizing benefits organizations in an uncertain environment more than organizations in a stable environment. Future research avenues of this understudied concept in operations management are discussed. Keywords Mindful organizing . High reliability organization . Operational performance . Environmental uncertainty 1 Introduction The concept of Mindful Organizing, rooted in the high reliability organizations literature, has been proposed as a practice that could help achieve reliability in operations (Weick et al. 1999; Weick and Sutcliffe 2001, 2007). High Reliability Organizations (HROs) are organizations that situate in high-risk settings where their operations are complex and the potential of error is overwhelming. Despite the high-risk conditions, HROs are consistently capable of achieving highly reliable, error-free perfor- * Hung-Chung Su hcsu@umich.edu 1 College of Business, University of Michigan – Dearborn, 19000 Hubbard Dr, Dearborn, MI 48126, USA mance (Roberts 1990; Rochlin 1993; Schulman 1993; La Porte 1996; Carroll 1998). Examples of HROs include aircraft carriers, emergency medical treatment teams, and nuclear power generation plants (Sagan 1993; Grabowski and Roberts 1997). Weick and Sutcliffe (2001) suggest that HROs "act mindfully by organizing themselves in such a way that they are better able to notice the unexpected in the making and halt its development^ (p.3). Researchers argue that HROs develop an overall collective mindfulness within organizations, which helps achieve the consistent, error-free performance (Weick et al. 1999). Mindful organizing is essentially the practice that allows HROs to organize themselves to act mindfully, to increase their collective mindfulness (Vogus and Sutcliffe 2012) and enable HROs to become the Bharbingers of adaptive organizational forms^ (Weick et al. 1999). Although the concept of mindful organizing is intriguing, empirical studies examining mindful organizing in an ordinary business setting are limited. Most recent studies are conceptual in nature (e.g. Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003; Prasad et al. 2015). In addition, previous empirical studies about high reliability organizations theory were mostly in education (e.g. Ray et al. 2011) and information systems (e.g. Anderson 2010). Recently, scholars have begun to empirically examine the effect of mindful organizing in healthcare (Vogus and Sutcliffe 2007a, b) and retailing (Ciravegna and Brenes 2016). Though few studies examine mindful organizing in operations management settings, this concept could have implications in operations management settings. In fact, Sitkin et al. (1994) pointed out that one interesting avenue for future research is to study the effective approaches used by high reliability organizations in operations management. A recent study also argues the principles of HROs can serve as role models for learning and development in manufacturing companies (Schulz et al. 2017). Following this inquiry, the main purpose of this paper is to explore the applicability of mindful organizing in an The impact of mindful organizing on operational performance: An explorative study operations management setting. We first explore the effect of mindful organizing on a business unit’s operational performance. Second, we explore the moderating role of environmental uncertainty. Developing mindful organizing could involve heavy investment in human resources (Vogus and Welbourne 2003; Vogus and Sutcliffe 2012) and could be a costly practice since it requires significant cognitive attention from organizational members (Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003; Levinthal and Rerup 2006; Ray et al. 2011). For high reliability organizations, mindful organizing is worth any costs because the consequence of failure is often catastrophic. However, for ordinary organizations, the value of mindful organizing may depend on the extent of changes in the environment (Barton et al. 2015). Third, we explore the moderating role of formalization. Several researchers argue that the existence of formal processes and procedures could help exploit benefits of mindful organizing (Vogus and Sutcliffe 2012). Figure 1 illustrates the overall conceptual model. Using a sample of 78 business units from 22 firms, the results indicate that mindful organizing has a positive effect on operational performance. Mindful organizing is also more effective in an uncertain environment than in a stable environment. The extent of formalization does not moderate the effect of mindful organizing on operational performance. 2 Relevant Literature and Hypotheses Development 2.1 Mindful organizing and operational performance Mindful organizing refers to the degree to which organizational members collectively engage in behaviors representing the five processes of collective mindfulness (Vogus and Sutcliffe 2007a, 2012). Weick and colleagues articulated five processes in HROs that promote collective mindfulness: preoccupation with failure, sensitivity to operations, reluctance to simplify, commitment to resilience, and deference to expertise (Weick et al. 1999). Preoccupation with failure refers to an attitude toward treating any lapse or variations in a system as a symptom of a larger 149 problem. An example behavior would be to articulate the mistakes you don’t want to make or report errors regardless of the degree of severity (Weick and Sutcliffe 2007). Near-misses also represent opportunities for learning to improve operational performance (Dillon and Tinsley 2008). Sensitivity to operations represents a constant awareness of daily operations in HROs. Example behaviors would be striving to understand an integrated big picture of operations at the moment. Reluctance to simplify refers to the tendency of resisting the urge to overly simplify. Example behaviors include encouraging organizational members to broaden their search for explanations and ongoing discussion of what’s being ignored and taken-for-granted (Weick et al. 1999). Being reluctant to simplification is a tendency to avoid classifying events into known categories. For instance, observing a near miss or unexpected issue in the operating process, employees that are reluctant to simplify might be more willing to collect more granular information and search for alternative explanations rather than discard the data point or attribute to the current system. Commitment to resilience manifests as striving to contain and correct any issues or problems before they worsen and cause more serious harm. Deference to expertise manifests as behaviors of allowing organizational members who have the most relevant expertise to address the issue at hand instead of relying on hierarchy (Weick and Sutcliffe 2001). The first three processes are the mechanisms that help anticipate potential problematic issues within operations for preventing failure. The last two processes focus on managing problems once they have taken place. Organizations with high extent of mindful organizing would exhibit behaviors that represent the five processes discussed above. They often question the status quo (i.e., preoccupation with failure) and are more alert and aware of subtle changes in the current environment (i.e. sensitivity of operations). High extent of mindful organizing requires organizations to be more suspicious about current performance and vigilant about subtle changes in operations, which allows organizations to sense and notice small anomalies that might later harm their product or service performance. For instance, mindful organizing allows organizations to detect a delivery Fig. 1 The hypothesized model Formalization Operational Performance Mindful Organizing Environmental Uncertainty 150 Su H.-C. issue before products reach customers or halt a production procedure that may later cause defects. Mindful organizing emphasizes commitment to correct anomalies and potential problems by members with relevant expertise (i.e. commitment to resilience and deference to expertise), which together enable organizations to correct problems rapidly and capture opportunities for operational improvement (Vogus and Welbourne 2003). A recent case study by Ciravegna and Brenes (2016) illustrates how the mindful organizing principles can help a food retailer, not a typical high reliability organization, to compete with the entry of a global retail giant. Some practical examples include an investment in the information system to gain a holistic picture of the current retail operations (i.e. sensitivity to operations), which help streamline internal processes and improve efficiency; the practice of a routine self-analysis and auditing to find potential issues in the retail operations (i.e. preoccupation with failure) (Ciravegna and Brenes 2016). Through routine self-auditing, the food retailer realized that even their most productive stores often reported problems. After consulting with frontline employees, the food retailer finds that the interruptions due to floods and landslides often damage the delivery routes. The food retailer then redesigns the supply network with help from internal experts and performs simulations to ensure the new delivery route is resilient to natural disasters (i.e. deference to expertise and commitment to resilience) (Ciravegna and Brenes 2016). Another example is a buyer outsourcing its maintenance function to a supplier. The buyer might lose the capability for early error detecting (i.e. preoccupation with failure) and become less mindful. The disadvantage of outsourcing call centers is that organizations may lose their capacity of getting real-time feedbacks about their products and services (i.e. sensitivity to operations) (Weick and Sutcliffe 2007). Thus, this study suggests the following: Hypothesis 1: Mindful organizing has a positive effect on operational performance 2.2 Moderating role of environmental uncertainty The effectiveness of mindful organizing may change under different types of environmental conditions as prior research suggested (Vogus and Sutcliffe 2012). Mindful organizing could be more in need Bwhere ugly surprises are most likely to show up^ (Weick et al. 1999). We posit that these ‘ugly surprises’ (e.g., supplier bankruptcy, late shipments, labor strikes) posing a threat to operations are more likely to show up in a more uncertain environment with constant changes. Environmental uncertainty has been defined as the degree of changes in the business environment due to changes in customers’ needs and the rate of product/process changes (Dess and Beard 1984; Pavlou and El Sawy 2006; Azadegan et al. 2013). To perform well under high uncertainty environments, organizations need to be sensitive to subtle changes within their environment to allow for adaptation. In a sense, mindful organizing improves a firm’s ability to better Bnotice^ subtle shifts sooner in their situated environment, which increases a firm’s adaptability to changes in the environment. Therefore, mindful organizing should help organizations perform better under uncertain environments. On the contrary, mindful organizing might not benefit the same organizations in a stable environment, since the required adaptability is low due to slow changes in technologies and customers’ needs (Zhang et al. 2012). The cost of maintaining high extent of mindful organizing may outweigh the benefits. As a result, we posit that mindful organizing would benefit organizations poised in a high uncertainty environment more than that in a stable environment. This line of argument suggests the following: Hypothesis 2: The level of environmental uncertainty positively moderates the effect of mindful organizing on operational performance 2.3 Moderating role of formalization The effect of mindful organizing might also depend on the extent of formalization, which represents the degree to which formalized rules and procedures are in place within an organization (Deshpande and Zaltman 1982). Formalization acts as a form of organizational control to regulate behaviors in organizations (Cardinal et al. 2004). As previously discussed, mindful organizing helps detect emerging issues or problems that pose a danger to operational performance and encourages dedicated commitment to rectify issues among organizational members. Having formalized rules and procedures in place provides a readily available problem-solving structure for organizational members to use, which increases information processing efficiency (Cardinal 2001). Employees can then respond to potential issues more effectively if formal and standardized procedures are in place. Further, from a preventive perspective, prior research in risk management emphasizes the role of risk monitoring procedures on mitigating the negative effects of risk (Ambulkar et al. 2015) Scholars have found that having formalized risk management procedures reduces ambiguity during supply chain disruptions and enable quick actions to mitigate the disruptions (Ambulkar et al. 2015). When there are formal risk monitoring processes in place, members under the influence of mindful organizing might be more willing to follow and execute the formal processes hence increase the likelihood of identifying potential operational problems. In a manufacturing setting, having formalized tools such as statistical process control could enable a mindful employee to better Bsense weak signals^ and identify potential issues in the existing operations (Su et al. 2014). Moreover, mindful organizing can promote The impact of mindful organizing on operational performance: An explorative study employee mindfulness and help reduce the tendency of blindly following the suggestions of existing rules and procedures. That is, mindful employees are more likely to treat a formal procedure (e.g., statistical process control) as a powerful learning tool to find the underlying root cause. In summary, formalized rules and procedures improve information processing efficiency and allow organizational members to monitor and mitigate operational risks more effectively. Further, employees under the influence of mindful organizing would apply the existing procedures more mindfully rather than simply following the rules, which further increase the effectiveness of mindful organizing. Mindful employees could more effectively correct problems such as late shipments if formal procedures exist. At the same time, if formal supplier evaluation procedure is in place, mindful employees are more likely to treat every incident as an opportunity to re-evaluate the existing suppliers. As a result, organizational members can detect and respond to issues and problems in operations efficiently and effectively if both mindful organizing and formal rules and procedures exist. Thus, we hypothesize the following: Hypothesis 3: The extent of formalization positively moderates the effect of mindful organizing on operational performance. 3 Data and method 3.1 Sample This study is explorative and the sample is convenient in nature. We first contacted several associations that the author has connections with to solicit participations in this study. Several firms eventually agreed to participate in an online survey and allow the author to gain access to multiple business units within firms. To reduce common method bias, different informants were designated to respond to different survey items. The online survey is divided into two parts: the operation managers respond to questions related to mindful organizing since they are closer to the Bfront line^ of operations. The general managers answer the survey questions related to performance, formalization, and environmental uncertainty. The final sample consists of 78 business units from 22 firms operating in four different manufacturing industries in the U.S: Food processing, Industrial, Electronic, and Chemical. 3.2 Measurements The mindful organizing construct is adapted from Vogus and Sutcliffe (2007a). This construct consists of nine items that assess the extent to which organizational members engaged in behaviors representing the five processes of collective mindfulness. The environmental uncertainty scale is adapted 151 from Jansen et al. (2006). The formalization scale is also adapted from a prior study (Deshpande and Zaltman 1982). Operational performance is measured as an organization’s product and service performance following prior research (Zu et al. 2008). All items are Likert-scale from 1 to 7. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is used to verify the reliability and validity of the constructs. Two survey items regarding mindful organizing are removed from subsequent analysis since the factor loadings are less than 0.4. All other factor loadings are significant (p < 0.01) with values ranging from 0.54 to 0.93 (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). The construct reliability and Cronbach α coefficients are higher than 0.7 for all constructs. Most fit indices are above the recommended cutoff (TLI = 0.92, CFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.082) which indicates a satisfactory fit (Bentler 1992; Hu and Bentler 1995). RMSEA is below the upper cutoff points (RMSEA = 0.066 < 0.08), which indicates an acceptable fit (MacCallum et al. 1996). The square root of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of each construct is also higher than the correlations between constructs as indicated in Table 1, which demonstrates discriminate validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981; Gefen and Straub 2005). Several control variables are considered in the analysis including: business unit size and industry types. Size is operationalized as the logarithm of the number of employees. Industry types are coded as dummy variables. Appendix Table 4 shows the measurement items of the constructs used in this study. 3.3 Analysis approach Since the survey data contains multiple business units within different firms, a random effect linear mixed model is used to accommodate unobserved heterogeneity at the firm level (Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal 2008; Cameron and Trivedi 2009). Random effect estimation method accounts for omitted variable concerns at the firm level, such as culture and policy, which can potentially affect the outcomes at the business unit level. Random effect estimation also has the advantage of considering both the within and between variations (Greene 2003). A random effect approach is preferred rather than a fixed effect approach since several firms provide only one business unit for the survey. Using a fixed effect approach will further reduce the sample size. Robust standard errors are reported to account for heteroscedasticity in all the estimated models (Cameron and Trivedi 2009). Variables are also centered to reduce multicollinearity and improve interpretations of the interaction effects (Aiken and West 1991). 4 Results Table 1 presents the summary statistics and the correlations between constructs. As expected, the correlation between 152 Su H.-C. Table 1 Mean, Standard deviations, and correlation Mean S.D. (1) (2) (3) (4) Operational Performance (1) 5.56 0.99 0.859 Firm Size (2) 5.83 2.03 −0.167† N/A Mindful organizing (3) Environmental uncertainty (4) 5.52 5.23 0.82 0.96 0.328** −0.106 −0.023 0.218* 0.685 −0.049 Formalization (5) 4.79 1.32 0.062 0.709 −0.020 0.067 0.016 (5) 0.826 † p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < .01, *** p < 0.001 The square root of AVE is shown on the diagonal of the correlation matrix mindful organizing and operational performance is positive and significant. Table 2 shows the sample distribution across industry types and size. Table 3 demonstrates the overall results of the random effect models. Model 1 contains results for control variables. Most control variables are not significant except for one industry dummy. Model 2 shows that mindful organizing has a positive effect on operational performance (b = 0.401, p < .01), which provides support for H1. Model 3 introduces the interaction terms, the results indicate that environmental uncertainty positively moderates the effect of mindful organizing on operational performance (b = 0.385, p < .001), but the interaction effect of formalization is not significant. Overall, the results support H2 but not H3. Figure 2 depicts the interaction plot to better understand the interaction effect using the 75th percentile as ‘high’ and 25th percentile as ‘low’ environmental uncertainty. As shown in Fig. 2, organizations can increase their operational performance considerably in the context of high environmental uncertainty compared to low environmental uncertainty. 5 Discussion 5.1 Theoretical contributions To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first study that explores the effect of mindful organizing on operational performance. Concepts from high reliability organizations theory Table 2 Sample distribution across industry Industry Number of business units % Food Processing Industrial Electronics Chemical Firm Size < 250 employees 250–499 employees 500–999 employees > = 1000 employees 26 14 21 17 33.33 17.95 26.92 21.80 35 8 10 25 44.87 10.26 12.82 32.05 have often been criticized as ‘too exotic’ to offer insights to ordinary organizations. This study, together with previous studies (Vogus and Welbourne 2003; e.g. Su et al. 2014), challenges this view. We find that mindful organizing, a practice developed by reliability-seeking organizations, is also effective for ordinary organizations seeking to increase operational performance. This result suggests that organizations situated in a less reliability-demanding environment than HROs can also benefit from mindful organizing. Interestingly, HROs are mostly situated in an external environment characterized by slow changes in customers’ needs. For instance, as typical examples of HROs, nuclear power plants and hospitals usually face stable changes in customers’ needs (customers always require stable electricity and quality healthcare) while facing limited number of competitors in a specific region (the entry barrier is typically high for building a new power plant or hospital) (La Porte 1996). Since external environments are mostly stable, mindful organizing is designed to prevent unexpected internal changes within HROs. Nonetheless, we demonstrate that mindful organizing has the potential to help ordinary organizations adapt to external changes in the environment. The moderating effect of environmental uncertainty reveals that mindful organizing is more effective in an uncertain environment. That is, mindful organizing behaviors such as being attentive to emerging changes, questioning the status quo, and committing to respond from errors do help organizations adapt to a changing environment. On the other hand, we did not find formalization moderates the effect of mindful organizing. Several studies argue that the objective of formalization is to achieve standardization, which may not be compatible with mindful organizing, a practice that fosters flexibility and adaptability within organizations (Weick 1987). Future research should further investigate this relationship to verify or rebuff this finding. Lean management has also been argued to be an antidote to “normal accidents” within organizations and supply chain disruptions (Marley and Ward 2013; Marley et al. 2014) but with a different focus compared to mindful organizing. Process management approach (e.g. Lean, Six Sigma) focuses more on simplification and standardization to reduce variations in the operational processes (Shah et al. 2008; Anand et al. 2009; Langabeer et al. 2009). In contrast, mindful organizing The impact of mindful organizing on operational performance: An explorative study 153 Table 3 Main results Dependent variable Model 1 Operational performance Model 2 Operational performance Model 3 Operational performance Firm Size −0.025 (0.063) 0.029 (0.080) 0.0316 (0.062) Industrial −0.087 (0.411) −0.062 (0.302) −0.718 (0.316) Electronics Chemical 0.491* (0.384) −0.005 (0.530) 0.592* (0.247) 0.276 (0.253) 0.447† (0.236) 0.038 (0.253) Environmental uncertainty Formalization −0.185† (0.110) 0.054 (0.051) −0.115 (0.084) 0.088 (0.057) Mindful organizing 0.401** (0.144) Mindful organizing * Environmental uncertainty Mindful organizing * Formalization N Overall R2 Within R2 Between R2 χ2 Δχ2 0.403*** (0.111) 0.385*** (0.081) 0.044 (0.105) 78 0.089 0.000 0.103 4.15 78 0.205 0.132 0.169 24.09 8.07* 78 0.276 0.248 0.252 106.66 26.60*** †p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < .01, *** p < 0.001 focuses more on increasing the variations in the Bcognitive^ infrastructure of an organization. In a sense, mindful organizing focuses on increasing the requisite variety of an organization as an antidote to normal accidents. We believe these two approaches can co-exist as an organization can implement process management to refine the internal processes and implement mindful organizing on the cognition aspect of an organization. That is, employees should strive to standardize operational procedures but still treat symptoms from an SOP with caution (i.e. preoccupation with failure) and resisting the urge to think all process problems can be resolved by standardization (i.e. reluctance to simplify) or avoid the danger of blindly follow the existing rules and procedures. This is like the simultaneous focus on flexibility and efficiency and on standardization and innovation in operations management described in previous research (Adler et al. 1999; Spear and Bowen 1999). Future research could further examine other possible antecedents discussed in the literature such as trust and heedful listening in an operations management context. Another interesting avenue of inquiry is to apply the findings to the project or team-level such as Six Sigma process improvement teams (Anand et al. 2010; Lifvergren et al. 2010). 5.5 5 4.5 Operational Performance 6 Fig. 2 Interaction plot -1.5 -1 -.5 0 .5 Mindful Organizing Low uncertainty (25th percentile) 1 1.5 High uncertainty (75th percentile) 154 In a sense, process improvement teams face a significant amount of internal and external uncertainties such as changing customer requirements, unexpected supplier issues, changing orders, and production delays. Mindful organizing may help team members engage in their work more mindfully and adapt better to uncertainties. 5.2 Managerial implications Practitioners can benefit from this exploratory study as well. This study presents a set of cognitive processes to enable an infrastructure for reliability performance such as safety and security. This cognitive infrastructure is often underdeveloped in ordinary organizations Bwhere people tend to focus on success rather than failure and efficiency rather than reliability^ (Weick et al. 1999). Weick et al. (1999) further suspect process improvement programs such as Total Quality Management often fail because the cognitive infrastructure is underdeveloped. This study provides preliminary empirical evidence showing that mindful organizing is an effective practice, which managers can apply to the field of operations management despite its origin in high-risk settings. The ever increasing complexity, generated by high coupling and interdependency, of today’s operations systems, increases the likelihood of accidents, errors, and mishaps (Perrow 1999). A system is unlikely to become completely free from accidents and errors, but applying mindful organizing related practices could be a solution for practitioners. In fact, accidents occur Bbecause the humans who operate and manage complex systems are themselves not sufficiently complex to sense and anticipate the problems generated by those systems^ (Weick 1987). Mindful organizing can be viewed as a way to increase the requisite variety (Ashby 1956) of organizational members to manage the complexity of systems. Most operations management tools and techniques such as Lean or Six Sigma often emphasize standardization and the reduction of wastes for process efficiency. La Porte and Consolini (1991) contended that mindful organizing and the pursuit of adherence to the standard operating procedure should co-exist. They argued that employees in high reliability organizations also follow standard procedures while simultaneously being alert to the small errors that could cascade into major system failures (p. 28). A prior study indicates that organizations which employ lean management may tend to overlook the risk posed from tight coupling in a complex system by eliminating too many non-value-added activities (Eroglu and Hofer 2011). Finally, managers can use this study’s measurement to assess the current extent of mindful organizing in their firms. One can foster the extent of mindful Su H.-C. organizing by enhancing the five underlying cognitive processes. Managers could foster preoccupation with failure by encouraging the employees to treat and report any error or near-miss as a warning signal of the future danger of the system; no matter how small the error is or how standard the procedures are. Managers could foster reluctance to oversimplify by ensuring time to learn about the near-miss or unexpected event and provide tools for collecting and analyzing such information. Sensitivity to operations can be enhanced by communicating frequently with the frontline personnel. Acknowledging that the frontline personnel are more experienced in understanding the current stage of the system and value their feedbacks. To foster the commitment to resilience, managers could encourage and allow decision-making to migrate to those with the highest expertise rather than relying on rank to ensure resiliency. 6 Conclusions and Limitations This study is not without limitations. The main limitation is the convenience nature of the sample and the small sample size because of the exploratory orientation of this study. Due to the nature and size of the sample, the empirical results should be viewed as explorative and not be viewed as conclusive. Also, the cost of generating mindfulness is not included in our empirical analysis of its impact on performance. Mindful organizing, environmental uncertainty, and operational performance are represented as single dimension constructs. The main constructs of this study can be much richer constructs since the measurement scales do not include all the dimensions. Future research can increase content validity by measuring the main constructs with multiple dimensions. Future research can also consider the implications of different individual aspects of environmental uncertainty and mindful organizing, and the effects on different dimensions of operational performance. Finally, the sample is limited to only certain industries and we use perceptual measures of performance. The operational performance for each unit is measured based on perceptions of single respondent so the external validity was not verified in this study. Even so, this study is the first step to demonstrate a promising concept that may have broad applicability in operations and supply chain management. We encourage future research to collect a more representative sample from a larger set of industries and objective performance data to confirm or reject our findings. We hope this article will encourage future studies to examine synergies between high reliability organizations and the operations management literature. The impact of mindful organizing on operational performance: An explorative study 155 Appendix Table 4 Measurements Mindful Organizing (CR = 0.86, alpha = 0.88, AVE = 0.47) To what extent do the following statements characterize your current business unit? We communicate information about our operations activities across all units We talk about mistakes and ways to learn from them * Factor loadings 0.54 We continue to seek areas of improvement in our current operations function * We discuss alternatives as to how to go about our normal work activities When discussing emerging problems with coworkers, we usually discuss what to look out for 0.60 0.71 When attempting to resolve a problem, we take advantage of the unique skills of our colleagues People here spend time identifying activities we do not want to go wrong When mistakes happen, we discuss how we could have prevented them 0.72 0.71 0.68 When a crisis occurs, we pool our collective expertise to attempt to resolve it 0.82 Environmental Uncertainty (CR = 0.75, alpha = 0.82, AVE = 0.504) How would you rate the following statements regarding dynamics in the business environment of your business unit? Environmental changes in our local market are intense. 0.76 Our customers regularly ask for new products and services. In our local market, changes are taking place continuously. 0.61 0.75 Operational performance (CR = 0.91, alpha = 0.91, AVE = 0.741) The following statements indicate your business unit’s level of product and service performance compared to the major competition in your industry over the last year. The quality of our products and services Customer satisfaction with the quality of our products and services The delivery of finished products and services to customer Conformance to customer specification Formalization (CR = 0.86, alpha = 0.89, AVE = 0.679) 0.81 0.87 0.91 0.85 How well do the following statements describe your business unit? Whatever situation arises, written procedures are available for dealing with it. Rules and procedures occupy a central place in this business unit. 0.75 0.93 We had standardized rules and procedures stating how to perform normal daily activities 0.78 *Removed due to low loading References Adler PS, Goldoftas B, Levine DI (1999) Flexibility versus Efficiency? A Case Study of Model Changeovers in the Toyota Production System. Organ Sci 10:43–68 Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage, Newbury Park Ambulkar S, Blackhurst J, Grawe S (2015) Firm’s resilience to supply chain disruptions: Scale development and empirical examination. J Oper Manag 33–34:111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2014.11.002 Anand G, Ward PT, Tatikonda MV, Schilling DA (2009) Dynamic capabilities through continuous improvement infrastructure. J Oper Manag 27:444–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.02.002 Anand G, Ward PT, Tatikonda MV (2010) Role of explicit and tacit knowledge in Six Sigma projects: An empirical examination of differential project success. J Oper Manag 28:303–315 Anderson CL (2010) It is risky business: Three essays on ensuring reliability, security and privacy in technology-mediated settings. University of Maryland, College Park Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: A review of recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103:411–423 Ashby WR (1956) An Introduction to Cybernetics. Chapman & Hall, London Azadegan A, Patel PC, Zangoueinezhad A, Linderman K (2013) The effect of environmental complexity and environmental dynamism on lean practices. J Oper Manag 31:193–212. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jom.2013.03.002 Barton MA, Sutcliffe KM, Vogus TJ, DeWitt T (2015) Performing Under Uncertainty: Contextualized Engagement in Wildland Firefighting. J Conting Crisis Manag 23:74–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/14685973.12076 156 Bentler PM (1992) On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychol Bull 112:400 Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (2009) Microeconometrics Using Stata, 1st edn. StataCorp, College Station Cardinal LB (2001) Technological innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: The use of organizational control in managing research and development. Organ Sci 12:19–36. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12. 1.19.10119 Cardinal LB, Sitkin SB, Long CP (2004) Balancing and Rebalancing in the Creation and Evolution of Organizational Control. Organ Sci 15: 411–431. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0084 Carroll JS (1998) Organizational Learning Activities in High-Hazard Industries: The Logics Underlying Self-Analysis. J Manag Stud 35:699–717. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00116 Ciravegna L, Brenes ER (2016) Learning to become a high reliability organization in the food retail business. J Bus Res 69:4499–4506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.015 Deshpande R, Zaltman G (1982) Factors Affecting the Use of Market Research Information: A Path Analysis. J Mark Res 19:14. https:// doi.org/10.2307/3151527 Dess GG, Beard DW (1984) Dimensions of Organizational Task Environments. Adm Sci Q 29:52–73 Dillon RL, Tinsley CH (2008) How Near-Misses Influence Decision Making Under Risk: A Missed Opportunity for Learning. Manag Sci 54:1425–1440. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1080.0869 Eroglu C, Hofer C (2011) Lean, leaner, too lean? The inventoryperformance link revisited. J Oper Manag 29:356–369. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jom.2010.05.002 Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J Mark Res 18:39–50 Gefen D, Straub D (2005) A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-GRAPH: Tutorial and annotated example. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 16(1):91–109 Grabowski M, Roberts K (1997) Risk Mitigation in Large-Scale Systems: LESSONS FROM HIGH RELIABILITY ORGANIZATIONS. Calif Manag Rev 39:152–162 Greene WH (2003) Econometric Analysis, 5th edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River Hu L-T, Bentler PM (1995) Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle RH (ed) Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Sage, Thousands Oaks, pp 76–99 Jansen JJP, Van Den Bosch FAJ, Volberda HW (2006) Exploratory Innovation, Exploitative Innovation, and Performance: Effects of Organizational Antecedents and Environmental Moderators. Manag Sci 52:1661–1674 La Porte TR (1996) High Reliability Organizations: Unlikely, Demanding and At Risk. J Conting Crisis Manag 4:60 La Porte TR, Consolini P (1991) Working in practice but not in theory: Theoretical challenges of High-Reliability Organizations. J Public Adm Res Theory 1:19–47 Langabeer JR, DelliFraine JL, Heineke J, Abbass I (2009) Implementation of Lean and Six Sigma quality initiatives in hospitals: A goal theoretic perspective. Oper Manag Res 2:13–27 Levinthal D, Rerup C (2006) Crossing an Apparent Chasm: Bridging Mindful and Less-Mindful Perspectives on Organizational Learning. Organ Sci 17:502–513. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc. 1060.0197 Lifvergren S, Gremyr I, Hellström A et al (2010) Lessons from Sweden’s first large-scale implementation of Six Sigma in healthcare. Oper Manag Res 3:117–128 MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM (1996) Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods 1:130 Su H.-C. Marley KA, Ward PT (2013) Lean management as a countermeasure for BNormal^ disruptions. Oper Manag Res 6:44–52. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s12063-013-0077-2 Marley KA, Ward PT, Hill JA (2014) Mitigating supply chain disruptions – a normal accident perspective. Supply Chain Manag Int J 19:142– 152. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-03-2013-0083 Pavlou P, El Sawy O (2006) From IT Leveraging Competence to Competitive Advantage in Turbulent Environments: The Case of New Product Development. Inf Syst Res 17:198–227 Perrow C (1999) Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies. Princeton University Press, Princeton Prasad S, Su H-C, Altay N, Tata J (2015) Building disaster-resilient micro enterprises in the developing world. Disasters 39:447–466. https:// doi.org/10.1111/disa.12117 Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A (2008) Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata, 2nd edn. Stata Press, College Station Ray JL, Baker LT, Plowman DA (2011) Organizational mindfulness in business schools. Acad Manag Learn Educ 10:188–203. https://doi. org/10.5465/AMLE.2011.62798929 Roberts KH (1990) Some Characteristics of One Type of High Reliability Organization. Organ Sci 1:160–176 Rochlin GI (1993) Defining Bhigh reliability^ organizations in practice: A taxonomic prologue. In: Roberts KH (ed) New challenges to understanding organizations. Princeton University Press, Princeton Sagan SD (1993) The Limits of Safety: Organizations, Accidents, and Nuclear Weapons. Princeton University Press, Princeton Schulman PR (1993) The negotiated order of organizational reliability. Adm Soc 25:353 Schulz K-P, Geithner S, Mistele P (2017) Learning how to cope with uncertainty. J Organ Chang Manag 30:199–216. https://doi.org/10. 1108/JOCM-08-2015-0142 Shah R, Chandrasekaran A, Linderman K (2008) In pursuit of implementation patterns: the context of Lean and Six Sigma. Int J Prod Res 46: 6679–6699 Sitkin SB, Sutcliffe KM, Schroeder RG (1994) Distinguishing control from learning in total quality management: a contingency perspective. Acad Manag Rev 19:537–564 Spear S, Bowen HK (1999) Decoding the DNA of the Toyota production system. Harv Bus Rev 77:96–108 Su H-C, Linderman K, Schroeder RG, Van De Ven AH (2014) A comparative case study of sustaining quality as a competitive advantage. J Oper Manag 32:429–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2014.09. 003 Sutcliffe KM, Vogus TJ (2003) Organizing for resilience. In: Cameron KS, Dutton JE, Quinn RE (eds) Positive Organizatoinal Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, pp 94–110 Vogus TJ, Sutcliffe KM (2007a) The impact of safety organizing, trusted leadership, and care pathways on reported medication errors in hospital nursing units. Med Care 45:997–1002 Vogus TJ, Sutcliffe KM (2007b) The safety organizing scale: development and validation of a behavioral measure of safety culture in hospital nursing units. Med Care 45:46–54 Vogus TJ, Sutcliffe KM (2012) Organizational mindfulness and mindful organizing: A reconciliation and path forward. Acad Manag Learn Educ 11:722–735. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle. 2011.0002C Vogus TJ, Welbourne TM (2003) Structuring for high reliability: HR practices and mindful processes in reliability-seeking organizations. J Organ Behav 24:877–903. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.221 Weick KE (1987) Organizational Culture as a Source of High Reliability. Calif Manag Rev 29:112–127 Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM (2001) Managing The Unexpected: Assuring high performance in an age of complexity, 1st edn. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco The impact of mindful organizing on operational performance: An explorative study Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM (2007) Managing The Unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty, 2nd edn. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM, Obstfeld D (1999) Organizing For High Reliability: Processes of Collective Mindfulness. In: Staw BM, Cummings LL (eds) Research in Organizational Behavior. JAI Press, Greenwich, p 81 157 Zhang D, Linderman K, Schroeder RG (2012) The moderating role of contextual factors on quality management practices. J Oper Manag 30:12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2011.05.001 Zu X, Fredendall LD, Douglas TJ (2008) The evolving theory of quality management: The role of Six Sigma. J Oper Manag 26:630–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2008.02.001