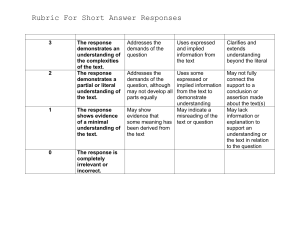

Contract Law: Implied Terms & Formation - University of Nairobi

advertisement

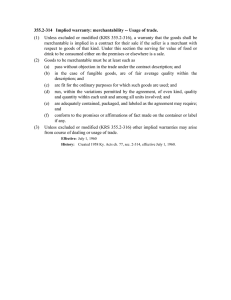

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI SCHOOL OF LAW CONTRACT LAW 1 1 Contents LIST OF CASES ......................................................................................................................................... 3 CONTRACT FORMATION AND CONSTRUCTION: IMPLIED TERMS OF A CONTRACT ..... 4 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................... 4 IMPLIED FORMATION OF A CONTRACT ........................................................................................ 5 IMPLIED TERMS OF THE CONTRACT .............................................................................................. 6 TERMS IMPLIED IN FACT................................................................................................................. 6 TERMS IMPLIED IN LAW .................................................................................................................. 9 TERMS IMPLIED BY CUSTOM ....................................................................................................... 11 TERMS IMPLIED BY TRADE USAGE............................................................................................ 11 CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................................................... 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................................................................................................................................... 13 2 LIST OF CASES Alpha Trading Ltd. v. Dunnshaw-Patten Ltd. [1981] 1 Ashington Piggeries v Christopher Hill [1972] AC 441 Beale v Taylor [1967] 1 WLR 1193 British Crane Hire Corp Ltd v Ipswich Plant Hire Ltd (1975) Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company [1892] EWCA Les Affreteurs Reunis S.A. v. Walford (1919) Luxor (Eastbourne) Ltd v Cooper (1941) 1 AC 108 Niblett v Confectioners Materials Co [1921] 3 K.B. 387 O'Conaill v Gaelic Echo (1958) O’Reilly v. The Irish Press Ltd. (1937) Priest v Last (1903)2K.B.148 Reigate v Union Manufacturing Co (Ramsbottom) Ltd [1918] 1 K.B. 592 Rowland v Divall [1923] 2 KB 500 Rubicon Computer Systems Ltd v United Paints Ltd (2000) 2 TCLR 454 Shirlaw v Southern Foundries (1926) Ltd [1939] 2 KB 206, 227 per MacKinnon LJ. Spring v NASDS [1956] 1 WLR 585 The Moorcock (1889) 14 PD 64 Trollope & Colls Ltd v North West Metropolitan Regional Hospital Board [1973] 1 WLR 3 CONTRACT FORMATION AND CONSTRUCTION: IMPLIED TERMS OF A CONTRACT INTRODUCTION Although it may be established that a contract exists and that it is enforceable, it may not always be easy to determine the terms of such a contract. The terms of a contract may have many sources, written and oral. When a court determines the scope and content of the normative relationship between contracting parties, it draws on a range of sources: the communications between the parties to the agreement, rules and principles of mandatory law (for example public policy, illegality), default rules, procedural and substantive rules that govern the ‘construction’ of the agreement.1 When there is a ‘gap’ in a contract, courts’ will effectively engage in restructuring the contract between the parties. The court applies a variety of strategies through an interpretative process (‘constructive interpretation’ in the widest sense),2 based on an assumed or hypothetical intention of the contracting parties, or supplement the agreement through substantive rules and standards outside of the agreement.3 BACKGROUND With rise of the market ascent of the contractual ‘will theory’ in the 19th Century,4 contract formation was conceptualized as the paradigmatic domain of private ordering, the very expression of private autonomy and the legal mechanism through which, on the basis of a dichotomous understanding of state and society, enterprising citizens structure their social relations mostly free from state interference.5 Thus, the role of courts was said to be limited to the enforcement of the contractual agreement as autonomously willed by the parties, i.e the lex contractus, therefore the courts do not write contracts for the parties, but merely enforces them. In constructing the contracts, the courts were guided by an intricate body of doctrine and social interactions of the parties and in so doing the courts draw not only on the ‘autonomous’ expressions of the parties’ intentions, but also on ‘heteronomous’ rules and principles of law, usage or accepted 1 PS Atiyah, The Rise and Fall of Freedom of Contract (1985) 67–85 McKendrick E, Contract Law: Text, Cases, and Materials (6th ed, Oxford University Press 2014) 3 Ibid 4 D Ibbetson, Historical Introduction to the Law of Obligations (1999) 220–61 5 J Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: an Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Polity Press, Cambridge, 161. 1991) 73–9 2 4 standards such as ‘good faith’ or ‘equity’.6 These standards can either inform the interpretation of the meaning of the communications themselves or operate as substantive standards that supplement the agreement.7 IMPLIED FORMATION OF A CONTRACT There are different modes of formation of a contract. The terms of a contract may be stated in words (written or spoken). This is an express contract. Also the terms of a contract may be inferred from the conduct of the parties or from the circumstances of the case. This is an implied contract.For example; If A enters into a bus for going to his destination and takes a seat, the law will imply a contract from the very nature of the circumstances, and the commuter will be obliged to pay for the journey. Offer and acceptance analysis is a traditional approach in contract law used to determine whether an agreement exists between two parties. An offer is an indication by one person to another of their willingness to contract on certain terms without further negotiations. A contract is then formed if there is express or implied agreement. A contract is said to come into existence when acceptance of an offer has been communicated to the offeror by the offeree. When it comes to offer, it may be express or implied. An offer implied from the conduct of the parties or from the circumstances of the case is known as implied offer. For Example; A owns a motor boat for taking people from Kisumu to Rusinga Island .The boat is in the waters at the dock. This is an offer by conduct to take passengers from Kisumu to Rusinga Island.. He need not speak or call the passengers. The very fact that his motor boat is in the waters near dock signifies his willingness to do an act with a view to obtaining the assent of the other. This is an example of an implied offer. With reference to acceptance, the assent may be express or implied. It is express when the acceptance has been signified either in writing, or by word of mouth, or by performance of some required act. Acceptance is implied when it is to be gathered from the surrounding circumstances or the conduct of the parties. For example; 6 7 Adams, J. N. and Brownsword, Roger, Understanding Contract Law (5th ed, Sweet & Maxwell 2007) Ibid 5 1. A enters into a bus for going to his destination and takes a seat. From the very nature of the circumstance, the law will imply acceptance on the part of A. 2. A’s scooter goes out of order and he was stranded on a lonely road. B, who was standing nearby, starts correcting the fault. A allows B to do the same. From the nature of the circumstances, A has given his acceptance to the offer by B. 3. In Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co, Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. (D) manufactured and sold The Carbolic Smoke Ball. The company placed ads in various newspapers offering a reward of 100 pounds to any person who used the smoke ball three times per day as directed and contracted influenza, colds, or any other disease. After seeing the ad Carlill (P) purchased a ball and used it as directed. Carlill contracted influenza and made a claim for the reward. Carbolic Smoke Ball refused to pay and Carlill sued for damages arising from breach of contract. Judgment for 100 pounds was entered for Carlill and Carbolic Smoke Ball appealed. The issue was whether who makes a unilateral offer for the sale of goods by means of an advertisement impliedly waive notification of acceptance, if his purpose is to sell as much product as possible? The court held one who makes a unilateral offer for the sale of goods by means of an advertisement impliedly waives notification of acceptance if his purpose is to sell as much product as possible . Thus acceptance by Mrs. Carlill took the form of her conduct by purchasing and consuming the smoke balls.8 IMPLIED TERMS OF THE CONTRACT As well as the express terms laid down by the parties, further terms may in some circumstances be read into contracts by the courts.. Sometimes it is assumed that implied terms are simply terms that the parties would have included had they thought of it. But judges very often imply terms into contracts, sometimes where it is arguable that the parties might not have agreed such terms themselves. These implied terms may be divided into four groups: terms implied in fact; terms implied in law; terms implied by custom; and terms implied by trade usage. TERMS IMPLIED IN FACT Terms implied in fact are ones which are not expressly set out in the contract, but which the parties must have intended to include. The courts have adopted two tests governing whether a term may be implied. The first is the "officious bystander" test, where a term is so obvious that its inclusion 8 Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company [1892] EWCA 6 goes without saying, and had an officious bystander asked the parties at the time of contracting whether the term ought to be included, the parties would have replied "Oh, of course". 9 In other words, if it can be established that both parties regarded the term as obvious and would have accepted it, had it been put to them at the time of contracting, that should suffice to support the implication of the term in fact. This test was laid down by MacKinnon LJ in Shirlaw v Souther Foundries (1926) when he stated that “…that which in any contract is left to be implied and need not be expressed is something so obvious that it goes without saying; so that, if while the parties were making their bargain, an officious bystander were to suggest some express provision for it in the agreement, they would testily suppress him with a common ‘Oh, of course!’”10 The alternative test for implication is that of "business efficacy", where the contract would be unworkable without the term. The leading case in this field is The Moorcook (1989). In this case the defendants owned a wharf and jetty on the river Thames which people could pay to use to load and unload their boats. The defendants contracted with the plaintiffs for the unloading of the plaintiffs’ boat, called The Moorcock, at their wharf. Both parties knew that the water level at the wharf was low and that the boat would have to rest on the river bed when the tide was down. This would be all right if the river bed was soft mud, but would damage the boat if it was hard ground. In fact, the boat was damaged when it hit a ridge of hard ground at low tide. The contract did not expressly state that the boat would be moored safely. The plaintiffs brought an action for compensation for the damage to the boat on the basis that there had been a breach of contract. The Court of Appeal implied a term into the contract that the boat would be moored safely at the jetty. Such a term was necessary to give the contract business efficacy. Otherwise the boat owner ‘would simply be buying an opportunity of danger’. The term had been breached and the action for damages for breach of contract was therefore successful.11 The decision in The Moorcook was for a long time misunderstood. However, Scrutton LJ Reigate v Union Manufacturing Co, clarified the position when he stated that: 9 Shirlaw v Southern Foundries (1926) Ltd [1939] 2 KB 206, 227 per MacKinnon LJ. Ibid 11 The Moorcock (1889) 14 PD 64 10 7 “A term can only be implied if it is necessary in the business sense to give efficacy to the contract, i.e. if it is such a term that it can confidently be said that if at the time the contract was being negotiated someone had said to the parties: ‘What will happen in such a case?’ they would both have replied: ‘Of course so and so will happen, we did not trouble to say that; it is too clear.’12 Further, Lord Pearson in Trollope and Colls Ltd v North West Regional Hospital Board stated that: “An unexpressed term can be implied if, and only if, the court finds that the parties must have intended that term to form part of their contract: it is not enough for the court to find that such a term would have been adopted by the parties as reasonable men if it had been suggested to them: it must have been a term that went without saying, a term necessary to give business efficacy to the contract, a term which although tacit, formed part of the contract which the parties made for themselves”13 From the above decisions, it can be stated that a term will only be implied if it is found that the contract will not work without it; it will not be implied just because it makes the contract more sensible, fairer or better Perhaps the most elaborative decision on the business efficacy state is to be found in the case of Alpha Trading Ltd v Dunnshaw Patten Ltd,14where one company was acting as agent for another in sales promotion. The agent was to receive commission based on the quantity sold. After contracting with the buyer, the principal pulled out of the contract. The cement company (Principal) settled with the third party for breach of contract, however, the Court of Appeal held that the business efficacy required that there was an implied term that the Principal would not withdraw from the contract so as to avoid the sale and leave the agent without commission, without such a term, it would have been pointless for the agent to be a party to the contract. Thus the cement company had breached this term and so the agent was entitled to an award of damages. It is clear that both the by stander and the business efficacy tests are subjective in nature: they ask what the parties in the case would have agreed, and not what a reasonable person in their position 12 Reigate v Union Manufacturing Co (Ramsbottom) Ltd [1918] 1 K.B. 592 Trollope & Colls Ltd v North West Metropolitan Regional Hospital Board [1973] 1 WLR 14 Alpha Trading Ltd. v. Dunnshaw-Patten Ltd. [1981] 1 13 8 would have agreed.15 Accordingly, efforts to imply terms in fact commonly fail for one of two reasons. First, a term will not be implied in fact where one of the contracting parties is unaware of the subject matter of the suggested term to be implied, or the facts on which the implication of the term is based.16 Second, a term will not be implied in fact if it is not clear that both parties would have agreed to its inclusion in the contract.17 TERMS IMPLIED IN LAW These are terms which the law dictates must be present in certain types of contract, regardless of whether or not the parties want them. For example, in a Sale of Good contracts there is an implied condition on the part of the seller that in the case of a sale he has a right to sell the goods, and that in the case of an agreement to sell he will have a right to sell the goods at the time when the property is to pass.18 Effect of the condition is that the seller transfers property/title in goods to the buyer. The Contract can be rescinded and the buyer has the right to recover monies paid (purchase price) as there is total failure of consideration. In Rowland v Divall,19the Plaintiff buys a car and sells it to sub buyer. It eventually turns out that the car had never belonged to the person that he had bought it from (the defendant). The Original owner claims the car and the plaintiff refunds the sub buyer. He then seeks to recover the whole purchase price from the defendant. The court held that the plaintiff is entitled to recover the whole purchase price. Further in Niblett v Confectioners’ Materials Co,20the Defendants sold 3,000 tins of preserved milk to the Plaintiffs. The goods arrived in England and were detained by customs authorities as they infringed the trademark of Nestle which was found to have the right to restrain the sale of the goods. The court held that the sellers had no right to sell the goods even though they had the power to confer good title to the buyer and thus the buyers were entitled to succeed in an action for damages. Further, there is an implied warranty in a sale of good contract that the buyer shall have and enjoy quiet possession of the goods.21 In Rubicon Computer Systems Ltd v United Paints Ltd,22 the 15 Catherine Elliott and Frances Quinn, Contract law (10th edn, Pearson Education 2015) Spring v NASDS [1956] 1 WLR 585 17 Luxor (Eastbourne) Ltd v Cooper (1941) 1 AC 108 18 Sale of Goods Act Cap 31 Laws of Kenya, s 14. 19 Rowland v Divall [1923] 2 KB 500 20 Niblett v Confectioners Materials Co [1921] 3 K.B. 387 21 Sale of Goods Act Cap 31 Laws of Kenya, s 14 (b) 22 Rubicon Computer Systems Ltd v United Paints Ltd (2000) 2 TCLR 454 16 9 supplier was installing a computer system for a buyer and wrongfully included a time-lock to it which denied the purchasers access to it. The court held that the claimants were in breach of warranty of quiet possession. In addition, there is an implied warranty that the goods shall be free from any charge or encumbrance in favour of any third party, not declared or known to the buyer before or at the time when the contract is made.23 Where the disturbance of the buyer’s possession is by a third party the buyer may be entitled to treat this disturbance as the responsibility of the seller if, as a result of any acts or defaults of the seller, some third party with whom the seller is in contractual relations with asserts an encumbrance or lien on the goods. In a contract of sale of good, there are certain terms that are implied by law. These terms are exceptions to the caveat emptor (Buyer beware) rule. First, there is an implied condition that the goods sold correspond with their description.24 If the sale is by sample as well as by description, it is not sufficient that the bulk of the goods correspond with the sample if the goods do not also correspond with the description.25 In Beale v Taylor,26 a second hand car was delivered for sale in a newspaper where Mr Taylor believed his car was a 1961 herald and advertised it for sale as such. Beale bought it and later found it was half of a 1961 herald and half of an older one welded together. Beale sues for a refund. The court held that the sale is by description and buyer was entitled to refund less scrap value. Moreover, there is an implied condition that where goods are bought by description from a seller who deals in goods of that description, there is an implied condition that the goods shall be of merchantable quality, provided that if the buyer has examined the goods, there shall be no implied condition as regards defects which that examination ought to have revealed.27 Furthermore, where the buyer, expressly or by implication, makes known to the seller the particular purpose for which the goods are required, so as to show that the buyer relies on the seller’s skill or judgment, and the goods are of a description which it is in the course of the seller’s business to supply (whether he be the manufacturer or not), there is an implied condition that the goods shall be reasonably fit for that purpose.28 Where goods have only one purpose or if it is the obvious 23 Sale of Goods Act Cap 31 Laws of Kenya, s 14 (c) Ibid, s 15 25 Ibid. 26 Beale v Taylor [1967] 1 WLR 1193 27 Sale of Goods Act Cap 31 Laws of Kenya, s 16(b) 28 Ibid, s 16(a) 24 10 purpose the courts will take it as a given that this was the particular purpose meant. E.g. food is for eating and milk for drinking. If no purpose indicated goods would be taken to be ordered for their normal purpose.29 Where goods are capable of use for a number of purposes particular purpose is deemed to be any purpose that could have reasonably been foreseen.30 In addition, there is an implied condition that the goods correspond with the sample. In the case of a contract for sale by samples there is an implied condition that, first the bulk shall correspond with the sample in quality.31 Second, that the buyer shall have a reasonable opportunity of comparing the bulk with the sample.32 Finally, that the goods shall be free from any defect rendering them unmerchantable which would not be apparent on reasonable examination of sample.33 TERMS IMPLIED BY CUSTOM Evidence of custom is admissible to add to, but not to contradict, a written contract. Terms can be implied into a contract if there is evidence that under local custom they would normally be there. In Ó Conaill v. Gaelic Echo,34there was no express term in the contract that stated that Dublin Journalist were entitled to pay holidays, however the court held that custom entitled Dublin journalist were entitled to paid holidays. The onus of proving a custom lies on the person claiming it.35 Custom must not contradict express terms: if it does, parties must be taken not to have intended the customary practice.36 TERMS IMPLIED BY TRADE USAGE Where a term would routinely be part of a contract made by parties involved in a particular trade practice or business, such a term may be implied by the courts. In British Crane Hire v Corp Ltd v Ipswich Plant Hire Ltd,37the owner of crane hired it to a contractor, who was engaged in the same sort of business. The court held that the hirer was bound by the owner’s usual terms, even though these was not stated expressly at the time of the contract. The reasoning of the court was that the owner’s terms were based on a model supplied by a trade association and were common 29 Priest v Last (1903)2K.B.148 Ashington Piggeries v Christopher Hill [1972] AC 441 31 Sale of Goods Act Cap 31 Laws of Kenya, s 17 (2)(a) 32 Ibid, s 17 (2) (b) 33 Ibid, s 17 (2) (c) 34 O'Conaill v Gaelic Echo (1958) 35 O’Reilly v. The Irish Press Ltd. (1937) 36 Les Affreteurs Reunis S.A. v. Walford (1919) 37 British Crane Hire Corp Ltd v Ipswich Plant Hire Ltd (1975) 30 11 in the trade and could therefore be implied into the contract in much the same ways as terms implied by custom. CONCLUSION The general position in law is that courts do not rewrite contracts and as such its role is to enforce the agreements between contracting parties. However, the court has discretion to establish implied terms of the contract, either created by facts, or by law (especially under public policy) or by customs or by trade usage. 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY Adams, J. N. and Brownsword, Roger, Understanding Contract Law (5th ed, Sweet & Maxwell 2007) Catherine Elliott and Frances Quinn, Contract law (10th edn, Pearson Education 2015) D Ibbetson, Historical Introduction to the Law of Obligations (1999) 220–61 J Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: an Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Polity Press, Cambridge, 161. 1991) 73–9 McKendrick E, Contract Law: Text, Cases, and Materials (6th ed, Oxford University Press 2014) PS Atiyah, The Rise and Fall of Freedom of Contract (1985) 67–85 13