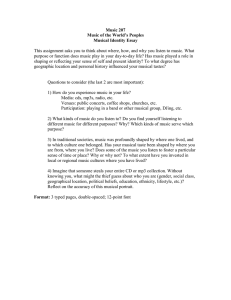

Applications of Music in Teaching Foreign Languages: Foundations and Practice Kyle Kuzman Advised by Professor Bettina Matthias, PhD An Independent Scholar Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Linguistics Spring 2021 Middlebury College Middlebury, Vermont I have neither given nor received unauthorized aid on this assignment Kuzman 1 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Introduction and Rationale 2 Literature Review Similarities Between Language and Music Applications of Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences Theory The Neuroscientific Case Cognitive Processing Similarities between Music and Language Cognitive Effects of Musical Training Music’s Cognitive Priming Potential Music’s Cognitive/Emotional Effects Hemispheric Lateralization in Musical and Linguistic Production Affective and Emotional Benefits Self-Confidence Motivation Reduced Anxiety Linguistic Benefits Phonological/Pronunciation Recall/Memory Vocabulary Acquisition Grammar Skills Foreign Language Comprehension and Oral Language Skills Conclusions 5 5 7 8 8 12 12 13 14 15 15 16 16 17 17 19 21 23 24 26 Survey of Middlebury College Language Professors Rationale and Methodology Results Teaching Experience, Self-Identified Musicality, and Teacher Training Correlations Between Musicality, Teacher Training, and Music Use Teaching Style and Approach Music Use for Specific Levels and Purposes Effects on Student Learning Attributed to Music Professor Opinions and Suggestions on Music in Language Curricula Professor Recommendations for Music Use in the Language Classroom Synthesis and Connections with the Literature 27 27 28 28 29 30 32 39 41 43 45 Conclusions, Limitations, and Suggestions for Further Research 47 Acknowledgements 50 Works Cited 52 Kuzman 2 Applications of Music in Teaching Foreign Languages: Foundations and Practice Abstract Many teachers believe that music is a very helpful tool in teaching languages, and plenty of people would agree. However, what research exists to support this notion? What do language professors at Middlebury believe about this practice, and do they utilize music in their teaching? In this project, I review literature from various academic disciplines such as neuroscience, linguistics, and pedagogy. I then provide a synthesis of the potential value of music as a language teaching resource. With this theoretical foundation, I analyze data from a survey of language faculty members at Middlebury College and its summer language schools, comparing and contrasting their perspectives with those found in the literature. Finally, drawing upon these varied sources, I aim to propose a strong conceptual foundation supporting the use of music in teaching foreign languages. Introduction and Rationale As an avid language learner and amateur musician myself, I have long found the use of music in learning a language to be one of the most motivating and effective methods to increase proficiency in a foreign language. However, I had never seriously and rigorously interrogated this belief and the potential evidentiary foundations which support it until now. My own prior knowledge came only from personal experience employing this technique in my own life, as well as anecdotal evidence from others who also find music extremely useful in their own language learning and teaching practices. For these reasons, I would here like to examine exactly which concrete, well-researched evidence exists to support the claim that music is indeed a highly effective pedagogical tool to both motivate and also significantly improve the linguistic capabilities of language students. Kuzman 3 Drawing upon my own personal experience, I consider music to be the most enjoyable way to come into contact with the sounds of a new and foreign language, especially when we cannot yet understand very much of the spoken language. Musically sung and performed language is a wonderful way to engage us not only intellectually, but also emotionally in our language learning journeys, as so many of us can strongly identify with, become excited about, and engage with music which we like and enjoy listening to. I would argue that indeed, music is truly one of the only enjoyable and interesting ways for us to come into contact with a foreign language at beginning levels, when we do not yet have enough experience to understand very much content, but rather need to focus on developing our Sprachgefühl, or “language feeling”, before we may expect to have meaningful interactions. It requires an inordinate amount of time for us to attune our ears, brains, and speech organs to the sounds of a new language before we are able to well replicate these novel sounds. An extremely efficient, effective, and enjoyable strategy to do so is by exposing ourselves to a wide variety of music in a given language. This, of course, cannot be done exclusively within the constraints of students’ school and homework time, but teachers can and should actively foster and encourage their students to explore the musics of their target language’s cultures, in the hopes of sparking joy and excitement in their students’ hearts which carry over into their lives outside of the classroom. Of course, when assigning certain songs as class- or homework, we can never be exactly sure who will appreciate a certain artist or song. However we should make the effort to consistently incorporate a wide range of musical styles, genres, and origins. This provides the best possible chance for most students to find music which they enjoy listening to and learning, and ideally, to be inspired to search for further such music in their own lives. Kuzman 4 Music is extremely effective tool to assist us in remembering specific sounds, words, and phrases. How many of us still remember songs that we heard and sang as very young children, many years and even decades later? When linguistic information is accompanied by a rhythm and a melody, it is much more likely to remain in our long term memory. Countless times, I have only successfully remembered a certain word or expression in a given language thanks to a particular line in a song which I know. Furthermore, I have also encountered the following highly motivating and satisfying benefit of listening to foreign language songs towards the beginning of our language learning journeys. While at first, we will not (and indeed, should not attempt to) understand every word, we can and should still listen to songs that we enjoy, attuning our ears to the unique flow of our target language’s prosody. Later on in our learning progression, after spending more time interacting with this language, we will be delighted to realize that we can now understand various aspects of a given song which eluded us before. This experience is very personally rewarding and reinforcing, serving as a strong example of the motivational benefits of this learning strategy. I propose music as an extremely valuable pedagogical and linguistic educational tool for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to: a strong body of neuroscientific research which shows how various structural similarities of music and language are processed in the same areas of the brain; multiple studies which display various benefits of music being integrated into language teaching, leading to significant increases in concrete, fundamental linguistic skills; and finally, the demonstrated increases in important psychological aspects of learning processes, leading to more positive learning experiences in the classroom. I believe that these benefits to language students strongly support my hypothesis that music is a highly effective pedagogical resource that can and should be effectively and widely employed in teaching foreign languages. Kuzman 5 Thus, I intend to offer a well-rounded overview of the applications of music in language teaching, supported by a robust literature review of various academic and scientific disciplines. In the second major section of this thesis, I discuss data collected from a survey of the language faculty at Middlebury College and its Summer Language Schools, in which I asked a series of questions regarding professors’ personal use (or lack) of music in their own language teaching practices. My rationale for this survey was to collect, compare, and contrast the information gathered in my literature review with experienced language professors’ beliefs and practices about the use of music in language teaching. I was also interested in understanding if professors would like to have more opportunities to employ music in their teaching, and whether they would use music more often if they could, in order to ascertain the current possibilities for educators to use such strategies. The results of this survey demonstrate strong support for incorporating music in language teaching from the great majority of professors who responded. Nearly all participants shared that they do indeed employ music in their language classrooms, at most or even all learning levels, and for a wide range of pedagogical purposes. Importantly, all but one respondent reported noticing positive effects on their students’ learning which they directly attribute to music. These survey results thus further strengthen my initial hypotheses that music-supported language teaching has concrete positive impacts on language learning outcomes and student motivation. Literature Review Similarities Between Language and Music Let us first discuss the striking similarities between the unique human forms of expression which are language and music. Patel (2003) credits Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983) with offering evidence that “[l]ike language, music is a human universal in which perceptually Kuzman 6 discrete elements are organized into hierarchically structured sequences according to syntactic principles” (674, italics mine). Thus, we may appreciate the importance that both of these systems of expression and communication may be found in every known human culture. Furthermore, they both share fundamentally similar structural and syntactic elements, in addition to relying on the same medium of audible transmission. Reflecting on the more affective aspects of these two kinds of human expression, Jett (1968) writes of the analogy that can be made between learning a language and learning music: “[like language, m]usic…also seems to mean much more than just the sum of its symbols…[and has] a feeling or emotional dimension far greater than the sum of [its] bare structures” (437). Thus, we can consider music and language to be similar and related forms of human expression, both of which which rely on sonic communication between human beings and contain far more emotional meaning and syntactic complexity than the simple sum of their parts. In a detailed comparison between the theories of time-span reduction (a method of analyzing musical structure using tree-like diagrams) and prosodic structure (prosody: the melodic flow of spoken language), Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983) found a very “significant parallelism between music and language”, perhaps more so than had ever been noticed before (329). Indeed, they proposed that there exists a notable overlap between these areas, as “both [musical and linguistic] capacities make use of the same organizing principles [‘temporal patterning’] to impose structure on their respective inputs” (330). Here we see a concrete example of a structural similarity – time-span reduction and prosodic structure – between language and music, which does not attempt to apply specific linguistic methodology to musical analysis, as had oft been the case in the past (5). Instead, these authors emphasize that temporal patterning (330) is an example of significant overlap between the fundamental structures of Kuzman 7 human music and language. This valuable contribution to the research shows that both language and music rely on extremely similar mechanisms to create order and structure within their sonic forms of communication. One further comparison we may make between music and language is in their syntax (Swain 20), the patterns and rules governing the arrangement of a [linguistic] system’s discrete components. Swain (1997) notes that “[b]oth language and music appear to create structures in a real-time stream of sound” (ibid.), musical structures being composed of sequenced arrangements of individual notes, and linguistic structure comprising the functional order of phonemes and words. Further on, Swain observes that both music and language constrain their “admissible sounds” and rhythms to a much smaller quantity than we have the capacity to understand, thereby facilitating our ability to discriminate between these sounds (25). In other words, though we technically are capable of understanding a wider range of sounds than our languages or musics contain, these systems limit their number of allowable sounds, thereby making it easier for us to distinguish between them. Swain here proposes a sound argument for the parallels between musical and linguistic syntax, which lends support to the theory that these two areas are indeed similar in multiple ways, and thus could potentially be brought together in the classroom to the benefit of language students. Applications of Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences Theory Through a pedagogical lens, many researchers have spoken to the educational benefits of pairing two different kinds of intelligences, the linguistic and the musical (DiEdwardo 2005; Failoni 1993; Fonseca-Mora 2000). Drawing upon Gardner’s (1987) theory of multiple intelligences, DiEdwardo (2005) suggests that pairing these two intelligences “advances student potential” (128) and “extends to motivational issues [and] comprehension goals” (130). Failoni Kuzman 8 (1993) proposes that we “could use students’ musical intelligence (and interest!) to achieve mastery of certain other skills” (97), drawing upon this specific intelligence to foster students’ learning in other areas. Furthermore, Fonseca-Mora (2000) argues that “the teacher should offer a varied gamut of activities to reach the different types of learners” (146), and also that musical intelligence “is highly relevant for language teaching” (ibid.). Here, a variety of authors speak to the belief that many benefits come from combining these two kinds of intelligences in the language classroom. However, what scientific research exists to substantiate these claims, and how might one concretely investigate such a hypothesis? The Neuroscientific Case Cognitive Processing Similarities between Music and Language In recent years, there has been much fascinating research from the field of neuroscience regarding the ways in which both linguistic and musical structures are processed in the brain. To wit, Patel et al. (1998) conducted a relevant event-related potential study (ERPs: “very small voltages generated in brain structures in response to specific events or stimuli” [Blackwood and Muir 96]). In this experiment, the researchers set out to “test the language-specificity of a known neural correlate of syntactic processing [the P600]” (717). To do so, they played participants “[m]usical sequences with out-of-key target chords” (724) as well as spoken sentences containing “syntactically incongruous words” (726), with the finding that these two stimuli elicited “statistically indistinguishable” P600 effects in the brain (ibid.). In other words, our brains react in an identical way when we hear words that do not fit properly within a certain sentence’s syntax, or musical notes which clash within their musical context. Patel et al. thus conclude that “the P600 does not reflect the activity of a speci cally linguistic (or musical) Kuzman 9 processing mechanism” (727), providing evidence that musical and linguistic cognitive processes coincide in the brain in important ways. Arguing against the notion that music and language have distinct, separate processing centers, Patel later proposed a “shared syntactic integration resource hypothesis”, or SSIRH (678). This hypothesis suggests that even though syntactic musical and linguistic representations may in fact be stored in separate, long-term posterior areas of the brain, the actual live processing of such syntactic information occurs in overlapping, frontal brain areas (674). Patel thus predicted that, if indeed this hypothesis is correct and there is significant overlap between the processing areas of syntactic information for both language and music, “tasks which combine linguistic and musical syntactic integration will show interference between the two” (679). This may raise the question of whether or not this combined processing could in fact have a potentially negative effect if we attempt to process too much linguistic and musical information at the same time. However, research on this particular question appears extremely minimal or even nonexistent currently, and so more research would have to be done in order to investigate this further. For the time being, as we shall see below, Patel’s SSIRH hypothesis has indeed proven to be highly viable according to multiple further studies. Brown et al. (2006) state that “phonological generativity is seen as the major point of cognitive parallelism between” music and language (2801) based on their PET (positron emission tomography) study on melody and sentence generation. Phonological generativity posits that “music and language are generative systems, relying on combinatorial operations to generate novel, complex and meaningful sound structures” (2798). In other words, both music and language are systems which combine basic building blocks of musical or phonemic information to generate larger strings of sound which convey more complex information. In this Kuzman 10 study, Brown et al. concur with Patel (2003) that a shared resource hypothesis indeed may be a plausible explanation for “common activations in the primary auditory cortex and subcortical auditory system for…music and language tasks” (2799), lending further support to this hypothesis. Their results were so noteworthy that they mentioned “a dramatic overlap in the areas of deactivation – principally in parieto-occipital areas – across all brain slices for both tasks” (2795, italics mine). “Deactivation” here refers to brain areas in which brain scans show less activity, which may suggest greater focus on a task at hand (Parsons et al. 211), as brain energy is concentrated in other areas. This finding strongly suggests that the cognitive processes involved in the generation of both linguistic sentences and musical melodies share a large amount of resources in the brain, which could substantiate the benefits of combining language education with musical elements. Later on, Fedorenko et al. (2009) provided further evidence for the SSIRH in their firstof-its-kind study of complex, grammatical sentences and simultaneous musical stimulation (5-6). They found that when musical integrations were more difficult (e.g. hearing out-of-key notes), so too was the processing of more complex grammatical sentences, which they interpreted as “additional evidence against the claim that linguistic processing relies on an independent working memory system” (6). Levitin and Menon (2003) also found evidence that supports the SSIRH in their study of non-musicians (2147), and similarly concluded that the “Brodmann Area 47 of the left inferior frontal cortex” is not in fact as language-centric as had been presumed before (2142). Furthermore, Maess et al. (2001) published a study indicating that musical syntax is processed in Broca’s area in the brain, “suggesting that these brain areas process considerably less domain-specific syntactic information than previously believed” (543). These various Kuzman 11 findings lend even further credence to the considerable overlap between language and music processing in the brain. Maess et al. also found that similar cognitive “effects were elicited in ‘non-musicians’… supporting the hypothesis of an (implicit) musical ability of the human brain” (544). This could provide evidence that certain cognitive musical processing abilities are indeed present in human beings regardless of their musical training or lack thereof. Similarly, Schön et al. (2008) found that “both musicians and non-musicians showed larger positivities to strong incongruities than to congruous endings in both music and language” (346-47). This means that when a grammatically highly unexpected or musically dissonant element was played for their test subjects, these subjects’ brains displayed similar strong, positive reactions, with “positive” in this case signifying “substantially activated”. Therefore, integrating music into language lessons could be extremely cognitively productive for all students, whether they identify as musical or not, as these brain activations have been shown to occur in students of all kinds. To summarize, this considerable body of evidence suggests that substantially overlapping brain areas are involved in the processing of both linguistic and musical information. However, it must be recognized that the majority of these studies were based on the brain’s reactions to unexpected stimuli, and it remains to be seen if the same results would hold true in terms of expected stimuli as well. Nevertheless, as we now know that our brains react similarly strongly to dissonance and incongruities in music and language, I propose that combining musically pleasing and grammatically correct language elements can lead to a positive and productive learning experience for all those involved. The wide range and great quantity of neuroscientific research discussed above leads me to propose that there may be a considerable cognitive connection between our linguistic and musical processing abilities. Therefore, we might then Kuzman 12 productively integrate this knowledge in practical ways: actively stimulating these brain areas in multiple ways by introducing language in musical form to our classrooms. Cognitive Effects of Musical Training As we have discussed above, musical training may not be inherently necessary to elicit reactions in the brain to dissonant musical elements. However, musical experience and expertise can indeed have a very strong correlation with enhanced linguistic processing abilities. We can see this in the work of Moreno (2009), who states that “music training influences behaviour, brain and, more specifically, auditory cortex and sound processing” (334). Moreno later elaborates on this point, noting that “musical expertise, by increasing discrimination of pitch…does facilitate the processing of pitch variations not only in music, but also in a foreign language” (338). Similarly, Schön et al. (2008) note that “musical training, by refining the frequency-processing network, facilitates the detection of pitch changes not only in music, but in language as well” (347). These findings may be put to practical use in the language classroom by incorporating music as an effective cognitive tool to train our ability to distinguish between sounds in a foreign language. The skill of pitch discrimination is an essential ability we must develop in our language students, potentially through musical repetition in order to provide initial and continued aural exposure to their target language’s sounds. This may be considered a highly beneficial and far more pleasant way of “drilling” L2 phonology, thus improving both listening comprehension and foreign language production skills. Music’s Cognitive Priming Potential One further cognitive connection between language and music was found by Koelsch et al. in an interesting study on semantic processing (2004). Employing both musical and linguistic priming techniques (priming: pre-disposing the brain to think of a certain concept), they Kuzman 13 discovered that music can “prime representations of meaningful concepts, be they abstract or concrete, independent of the emotional content of these concepts” (306), just as language can. This study consisted of playing participants multiple musical excerpts which were associated with specific words (302). One third of these determinations depended on composers’ own descriptions of their music, while the rest were related to musical characteristics, such as the words narrowness and wideness being paired with closed and open musical intervals, respectively (303). Importantly, all subjects were not musically trained (305) and were unfamiliar with the music they heard, and thus could not have any previous associations with these excerpts (303). The authors specify that they are not attempting to propose that both music and language share the same semantics; rather, they believe their results suggest that “music transfers considerably more semantic information than previously believed” (306). This study displays that music may play an important cognitive role in semantic terms: music is able to prime our minds to recall a certain word, just as an excerpt of language can do. Music’s Cognitive/Emotional Effects Finally, music has been shown to have significant effects on our brain activity and our emotions. Brown et al. (2004) created a study in which they played unfamiliar instrumental music to 10 participants while performing PET scans of their brains (2033-34). The researchers found that this exposure to novel music spontaneously activated both limbic and paralimbic brain regions (2035), which these authors surmise to be “involved in emotional processing” (2036). These activations were seen primarily in the left brain hemisphere, which is thought to support positive emotions, “perhaps reflecting subjects’ positive aesthetic responses” (2035). Brown et al. thus concluded that new and unfamiliar songs can elicit strong positive emotions through neurological reactions, just as our familiar favorite songs can do (2036). It is important to note Kuzman 14 that the songs in this study did not contain words, however we may infer that pleasant lyrical songs may also have the same effect on students. Thus, when we introduce music which students find pleasant, we may in fact be activating specific positive emotion processing centers in their brains, which can only lead to a more productive learning experience for all those involved. Hemispheric Lateralization in Musical and Linguistic Production While the previous study showed significant activation in left hemisphere regions related to positive emotion during music listening, Jeffries et al. (2003) studied the differences between brain activations when we speak song lyrics versus singing them (749). These researchers also utilized PET scans in order to study 20 subjects while they both spoke and then sang the words to a familiar song (750). Results displayed a significant difference between these two activities, in that generally, left hemisphere regions were more active for speaking, while right hemisphere regions showed more activity when subjects were singing (ibid.). The authors thus suggest that there is significant hemispheric lateralization in terms of spoken versus sung language, and that these two activities rely on differentiated systems in the brain (752). These findings may at first appear to contradict the previous conclusions that language and music are processed in the same brain areas; however, we are here discussing the active production of musically sung language, and not the receptive processing of musical input in the brain. Jeffries et al. conclude their study by proposing that the “[a]ctivation of these regions may also support the fluency-inducing effects of words produced in melody” (754), suggesting that musically sung language contributes to higher fluency in a given language. Further research is needed in order to continue studying the ways in which this lateralization contributes to interactions between linguistic and musical production, and the potential applications to language pedagogy. Kuzman 15 Affective and Emotional Benefits Self-Confidence The aforementioned neurological processing parallels between music and language may point to the potential cognitive benefits of pairing these two domains in the classroom. However, how might we see the evidence of these benefits in the practical terms of psychological affective and emotional benefits? Multiple studies point to positive effects which language students experience thanks to this particular pedagogical approach. Let us here consider the potential for positively influencing Krashen’s (1982) affective filters, those factors such as self-confidence, motivation, and anxiety whose respective levels may either foster or hinder our ability to successfully acquire knowledge in a foreign language (31). Krashen states that “[p]erformers with self-confidence and a good self-image tend to do better in second language acquisition” (ibid.). In terms of a potential relationship between music-integrated teaching and self-confidence, Israel (2013) found that many English learners in a secondary school language classroom in South Africa increased their level of “confidence in using their limited knowledge of English visibly” thanks to the incorporation of music (1360-61). This study further found indications that “music enhances…self esteem…and general self confidence (ibid.), effectively influencing this particular aspect of these students’ affective filters. In a personal account of his own language learning strategy employing Hip Hop, Kao (2014) found that “[s]trategically learning language with music can build up confidence and motivation” (Kao and Oxford 114). Thus, we can acknowledge the integral importance of self-confidence in learning to speak a new language, and the effective role that music may play in helping to foster such confidence in language learners. We may also consider that these findings may be strongly linked to Brown et Kuzman 16 al.’s (2004) research on music’s impact on positive emotion processing centers in the brain, as discussed in detail above. Motivation Secondly, let us discuss the increase in student motivation which music in the classroom may bring about. DiEdwardo cites music as beneficial in improving student motivation in the classroom, particularly noticing “positive transformational changes in classroom patterns” (128). In a study which tested the effects of an experimental curriculum including “word games, songs, and stories” (38), Ajibade and Ndububa found a statistically significant difference between their control and experimental groups, suggesting that these alternative activities effectively increased students’ motivation levels (37-39). The progression of art affecting motivation is succinctly summarized by Lems (2018), who draws upon Posner et al. (2008): “the process begins with curiosity, which is piqued by experiencing an art form; this curiosity creates motivation and interest and leads to heightened attention…[and] in that alert state of heightened attention, new learning occurs” (15, italics mine). Thus, we see a wide range of studies which display the positive, quantitative as well as qualitative effects which music has on students’ motivation when it is effectively integrated into their learning. Reduced Anxiety Finally, let us consider the benefits of reduced anxiety which may be brought about by incorporating music into the language classroom. To quote Lems (2018), “student choice—and the fact that the general topic is music—reduces anxiety” (19), referring to the practice of allowing students to actively engage in music selection. Employing Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope’s (1986) foreign language classroom anxiety scale (FLCAS), Dolean and Dolean (2014) performed an experiment with 60 Romanian 7th graders learning English (513). About one Kuzman 17 quarter of these students made up their experimental group, while the remaining three quarters constituted three control groups (514). After a four-week long program wherein the experimental group was taught English through songs (ibid.), only this group displayed a significant reduction in anxiety (-24%) as measured on the FLCAS versus an average of only -3% for the control groups (516-17). This provides strong support that even after only one month of musicallyintegrated language learning, foreign language anxiety may be precipitously reduced. Later, Dolean (2016) conducted a further study involving two experimental groups of 8th graders, one displaying high levels of anxiety and the other low levels, as well as two control groups with statistically similar initial FLACS results (643). After a ten-week period in which the experimental group learned one novel French song per week (644), the highest significant decrease in anxiety was found for the initially high-anxiety experimental group, with no significant decrease found for the initially low-anxiety group (646). These results suggest that music may be a highly effective tool to lower high levels of foreign language anxiety in the classroom, while not having much of such an effect on those students with initially lower levels of anxiety. Linguistic Benefits Phonological/Pronunciation Finally, we turn to the concrete linguistic benefits of learning languages with music incorporated into the curriculum. Perhaps the most apparent of these benefits is that of pronunciation in the target language, of increased phonological awareness and ability for the students engaged in this musical learning process. Lems (2018) succinctly summarizes a process by which this improvement occurs, stating that both musicians and language learners “make ever-closer approximations of the target sounds until they reach a level of ease and enjoyment, or Kuzman 18 ‘fluency’” (15). This necessary progression of approximations may well be rendered much more effective, enjoyable, and encouraging by encountering sounds within songs. In evidentiary terms, Farmand and Pourgharib (2013) conducted a study of 30 intermediate 15-17 year-old English language learners, dividing these students randomly into two groups and assigning each the same English song lyrics and vocabulary drawn from them (842). However, the experimental group received eight interactive, musical sessions of fifteen minutes each over the course of one month, learning to sing along to songs in English (ibid.). After this experiment, post-test results showed a significant improvement in pronunciation for the experimental group, compared to no improvement for the control group (843). This was measured both by recordings of the students’ pronunciation, as well as a ten-item pronunciation test (ibid.). Thus, we see a concrete example of improvement in pronunciation thanks to music, even in such a short amount of time as one month and only two combined hours of musical instruction time. In a more technical study, Moradi and Shahrokhi (2014) investigated the potential effects which listening to music could have on students’ articulation of vowels, intonation, and stress patterns (129). In their study of 30 female English learners in elementary school, the authors divided this group evenly into an experimental and a control group, each of which had 25 sessions in which 20 minutes each were allotted to the experiment (131). Students in the experimental group learned to sing along with an English language song by first receiving its lyrics, then hearing the song multiple times and attempting to memorize it (132). The control group read the written lyrics of the same song, and instead of hearing the song itself, the lyrics were read aloud multiple times by the researchers before they attempted to sing along (ibid.). Students’ pronunciation was recorded in both a pre- and post-test (131), after which the researchers scored them on various categories such as “intonation, stress recognition and Kuzman 19 pronunciation” (133). They found that music indeed has a significant effect on the children’s pronunciation (134), an even more significant effect on their intonation (135), and a similarly highly significant effect on their stress patterns (136). This study provides strong evidence that multiple important pronunciation patterns may be effectively enhanced by learning to sing songs in a foreign language, an effect which was not seen from learning to read these songs’ lyrics aloud. Recall/Memory One other important linguistic and cognitive skill which has shown positive correlations with the use of music in language teaching is that of recall. According to Mobbs and Cuyul (2018), “[w]ithin the context of L2 learning, music stimulates thinking and helps improve skills such as verbal…and auditory memory” (22). This could in part be due to the neuroscientific findings above which determined music’s power to prime certain linguistic concepts in our minds (Koelsch et al. 2004) Furthermore, Staum (1985) observed that “automaticity of speech is enhanced primarily by inflectional and rhythmic fluency. This enhancement may be benefited by tonal and rhythmic pairing” (40). In other words, in order to increase the verbal fluency of our students, we may pair music and rhythm with linguistic instruction, enhancing their learning of important linguistic skills. In this same study, Staum relates an experiment wherein 169 undergraduate and graduate students with limited to no experience with Russian were assigned to three groups, all of whom were taught ten Russian words and phrases each (32). The first group heard words paired with melodies, the second heard words with rhythmical patterns that mirrored the natural stress of the words, and the third heard simply spoken words (ibid.). Staum found that after their exposure to these unfamiliar Russian words and phrases, “the melody group achieved an average of 34% accuracy on the ten questions, the rhythm group achieved 27%, and the Kuzman 20 control group achieved 23% accuracy” (37). This provides us with convincing evidence that melodic music is the most effective way to increase vocabulary retention in a foreign language, followed by rhythmic accompaniment, with plainly spoken words being the least effective. In a study of 94 college students enrolled in beginning Spanish classes, Salcedo (2010) designated two comparison groups and one control group in an experiment on text recall when music is incorporated into the classroom (23-24). The experiment consisted of six sessions in which one comparison group listened to a song in Spanish, while the other group heard the same song’s lyrics as a spoken recording by a native Spanish speaker with similar demographic characteristics as the song’s artist (24). After completing these six sessions, students were given a cloze (“fill-in-the-blanks”) test on the lyrics they had learned soon thereafter, which was then followed up with a longer-term recall test two weeks after the end of the experiment (ibid.). In Salcedo’s results analysis, the researcher found that there was indeed a statistically significant difference for two of the three songs which had been learned, and that the musical comparison group outperformed the text group on every test which they took (24-25). No significant difference was found between groups on the delayed text recall test (25), which this author believes may be attributed to not enough time passing between the end of the experiment and the follow-up test, perhaps indicating that the material was not allowed to enter into long-term memory (26). However, the fact that the musical group performed better on every test and that these differences were statistically significant for two out of three songs further supports music’s effectiveness in increasing recall of textual items in a foreign language. Still, more research is needed on the potential effects on recall of longer language chunks than singular words, as well as questions of linguistic generativity. Kuzman 21 Vocabulary Acquisition Similarly, music has also been shown to have concrete positive effects on vocabulary acquisition. Li and Brand (2009) conducted a study of 105 ESL graduate students who had an average of an upper intermediate English level and attended a university in China (77). These students were divided into three equal groups, one of which received exclusively musical English training, the second of which had musical training half of the time, and the third of which acted as the control group (ibid.). Each group was taught by the same instructor and received six 90minute treatments over the course of the experiment after being pre-tested (ibid.). All groups had approximately the same level of English before the experiment began (79), however post-test results showed that the all-music group scored significantly higher than both other groups on measures of “vocabulary, language usage, and meanings” (79-80). These results offer evidence that music may provide significant benefits even to more advanced foreign language learners in terms of vocabulary acquisition. In a well-constructed study involving 26 native French speakers with a mean age of 23, Schön et al. (2008) ran a series of three experiments which employed “six three-syllable nonsense words (hereafter words)” which are plausible within French phonological constraints, played in a pseudo-random order (977). In their first experiment, participants heard these words repeated continuously in a spoken stream of syllables for seven minutes, and were instructed to listen carefully but not try to analyze them (978). They were then requested to determine whether one previously-heard “word” or one “part-word” composed of the same syllable set “was most likely to be a word from the language” (ibid.). Part-words combined a syllable pair and a syllable from the beginning and end of “words” that had been played in sequence in the experiment, thus testing word boundary discrimination abilities. Results showed that participants did not Kuzman 22 successfully identify words significantly more often than chance would dictate after seven minutes of auditory exposure (ibid.). That is to say, listening to these words being spoken continuously for seven minutes did not cause any significant effect on the participants’ ability to discriminate between their boundaries. In the second experiment, these same syllables were sung instead of spoken to participants (978), each word following the same melodic contour of either three rising or falling notes (979). This meant that in 12 out of 30 transitions between words, the pitch contour was continuous – in other words, it either continued rising or falling, thus rendering word boundary discrimination more difficult. However, results proved that participants in fact successfully learned and identified the words 64% of the time when they were set to musical notes, a statistically significant increase over the first experiment. Thus, the researchers concluded that “the simple addition of musical information allowed participants to discriminate words from part-words” (ibid.), strongly supporting the potential power of music to aid in linguistic discrimination. In order to parse out why exactly this was the case, the researchers conducted one final study in which the same words were played, this time however with musical phrase boundaries not directly mapped onto the words as in the previous experiment (980). Results showed that participants performed significantly better than by chance, answering correctly 56% of the time and thus placing the third experiment’s results exactly in between those of the previous two (981). We can thus conclude from this study that music is indeed highly effective at facilitating our acquisition and discrimation abilities for novel words, even when linguistic and musical boundaries do not line up. Kuzman 23 Grammar Skills One further linguistic area in which music may significantly aid educators in their teaching is that of grammar. Indeed, “[m]usic is a great natural introduction to new grammar forms, in many ways resembling our effortless first-language acquisition” (Lems 18), a quite astute observation. In a study of 38 university students, Kara and Aksel (2013) performed a tenday experiment over eight lessons on the effects of musical grammar instruction on half of these students, while the other half served as the control group (2741-42). A limited number of specific English language grammar points were selected for both groups to learn concurrently, and instructors employed the same teaching methods with each group, differing only in the use of English language songs in the experimental group (2742). Students in the musical group heard English songs twice per lesson for ten minutes, and in the last lesson had the chance to sing along with songs played on guitar by a music teacher (ibid.). After the conclusion of the experiment, post-test results showed a statistically significant difference between the increases in both groups’ grammatical recall abilities, with the experimental group gaining seven points versus a gain of only four points for the control group (2743). So we observe here an important gain in grammatical ability when a group of students is given the chance to learn certain grammar points through songs rather than traditional methods, even in a very short experiment such as this one. In a study of 72 ESL students in an elementary school, Fagerland (2006) tested the effect of lyrical musical instruction on the learning of four grammar structures determined to be difficult for these grade levels. The music used in this study was designed by the researcher personally, who considers pre-recorded or traditional music not to be ideal pedagogical tools for this purpose (50-51). This study was conducted over the course of five weeks, with one half-hour Kuzman 24 class each day. After the first week was dedicated to a pre-test, one each of the four chosen grammar points was taught each week thereafter (51). Both experimental and control groups received the same instruction materials and activities, with the pedagogical songs being the only difference between them (52). Post-test results showed that for three of the four tested grammar points, the experimental group indeed outgained the control group, with the control group only performing better in terms of the plural “s” construction (53). The other grammar points in question were: singular and plural reflexive pronouns; “there is” vs. “there are”; and naming “another and I” (48). Fagerland thus hypothesized that the plural “s” was not easy for students to identify within the complex flow of musical input; in this context, word boundaries merge together and this morpheme may have seemed attached to beginnings rather than ends of words (56). Overall however, all three of the other and arguably more difficult grammar points showed consistently more improvement for the group which received musical instruction, further supporting the hypothesis that music may effectively aid in learning grammatical concepts. Foreign Language Comprehension and Oral Language Skills One further linguistic capability with which music may have a positive correlation is that of foreign language comprehension. Swaminathan and Gopinath (2013) investigated this relationship in a study of 76 schoolchildren, of whom roughly half had significant musical training of at least three months and spoke a language other than English at home (165). The researchers tested their subjects on both the “Malin’s Intelligence Scale for Indian Children verbal subscales (MISIC 1969)” as well as an adapted version of the Schonell Reading Test’s word list (Schonell and Schonell 1950) in order to compare these children’s English language abilities (166). Both groups were demographically extremely similar, however the musicallytrained group displayed significantly better verbal, comprehension, and vocabulary skills in Kuzman 25 English (167). In order to remove the possibility of interference from Western and other kinds of musical training with potential connections to English, only the scores of children trained in classical Indian music were considered in the second part of these authors’ analysis (ibid.). Their findings were similar to the initial results, in that the classically-trained children displayed higher competence in both comprehension and vocabulary subtests (ibid.). These results may indicate that musical training is beneficial to students’ linguistic abilities in any foreign languages, regardless of musical experience in the target language, or lack thereof. In a long-term study of eighty elementary school students, all of whom spoke Spanish at home and were enrolled in a bilingual school program, Fisher (2001) randomly assigned all of these students to four different classroom teachers for a period of two years (41). Two of these four teachers consistently employed music in their classrooms while the other two did not, however all teachers planned their curriculum together, and so they all taught the same content at the same time (ibid.). The teachers who used music led activities such as singing songs together with students at the beginning of each class (44), integrating word scramble games based on song titles (45), and introducing books with accompanying musical CDs as opposed to just traditional audiobooks (46). Students were assessed on their oral language skills and reading achievement at the beginning of this experiment and then again towards its end, some 19 months later (41-42). When tested after two school years of participation in this experiment, students who attended the musically-integrated classrooms displayed significantly higher scores on the Student Oral Language Observation Matrix (developed by the California Department of Education, 1981), with an average score of 13.2 compared to only 8.2 for students in non-musical classrooms (43). This suggests that having music integrated into their language classrooms considerably helped students to improve their oral language abilities. Similarly, on the Yopp- Kuzman 26 Singer Test of Phoneme Segmentation [proper discrimination of individual phonemes] (Yopp, 1995), the average score for the music-integrated classes was 19.5 compared to 17.1 for nonmusic-integrated students (44). Finally and perhaps most notably, in terms of the Developmental Reading Assessment (Beaver, 1997), fully “ten students in the music rich classroom read at grade level in English and Spanish whereas only one student in the non-music classroom read at grade level in English and Spanish” (43), a tenfold difference between these two experimental groups. It is important to note that when pre-tested before beginning this experiment, no significant differences were found in the results for any of the three above-named tests (ibid.). And within the span of a mere two school years, the number of students reading at grade-level in the music-integrated group grew by a full order of magnitude more than those who did not learn English with music. Conclusions As we have seen in the above literature review, a wide range of research exists concerning the connections and concrete benefits of the integration of music in the language learning process. These findings span the gamut of musical and linguistic theory, neuroscience, practical pedagogy, and applied linguistics. We have discussed the striking structural similarities between language and music in their organization of sound elements. We have reviewed how both music and language are processed in very similar or identical areas in the brain, and that this may be a boon to the combination of language and music in educational settings. We have considered the multiple psychological benefits of integrating music, namely increased selfconfidence and motivation and reduced anxiety among students. And finally, we have determined that music may provide myriad concrete linguistic benefits in terms of phonology and pronunciation, memory and vocabulary recall, grammar skills, and foreign language Kuzman 27 comprehension. These varied sources of research provide a strong base of support for the hypothesis that music effectively increases student motivation and leads to improved language learning outcomes. Now, how might we further investigate the real-world practical applications of these findings and their use by experienced professionals? Survey of Middlebury College Language Professors Rationale and Methodology In order to gather real-world data from practicing and experienced language professors, I drew inspiration from the above literature review to design a survey on beliefs and practices regarding music in their language teaching. My primary goal with this survey was to gather the opinions and advice of experienced professors in order to better inform our understanding of the practical applications of music in language education. Additionally, I then compared and contrasted these professors’ responses with the information collected in my literature review, in order to propose a synthesis based on these two different types of data. The end goal was to propose a synthesis of the findings common between the literature review and novel survey, and provide encouragement to language teachers who may be hesitant or feel that they lack the experience or expertise to use music in their classrooms. My survey, entitled “Music in Language Teaching”, contained 14 questions with a mix of multiple-choice, open-ended text-entry, and Likert scale answer options. I attempted to strike a sound balance between question formats, and frame my questions simply and clearly to make the survey straightforward and facilitate completion. I emailed the finalized survey to each of the 9 language department chairs (representing 10 languages) at Middlebury College (VT) and the directors of Middlebury’s summer language schools (12 languages), requesting that they please forward my message and survey on to their respective language professors. Twenty-two Kuzman 28 complete and two incomplete responses were received; the latter were discarded as to maintain integrity for data analysis. Qualtrics was used as the survey instrument, and no identifying information was requested from participants in order to maintain full anonymity and allow for the most honest and candid responses from all parties. It must be taken into consideration that this survey was self-selecting, and so does not contain an entirely representative sample of all language professors at Middlebury College. Additionally, we must recognize that this college represents only a very small subset of all language educators, as it is an elite, private, US institution and thus does not nearly encompass the entirety of perspectives the world over. Nevertheless, we may still gain valuable insight into language education practices from this data, as respondents possess considerable practical teaching experience, which they generously contributed to this research. After the survey closed, data was exported and cross-tabulated for analysis. Coding was based on the following research questions: How, when, and why do professors use music in language teaching? What effects have they seen on their students? Based on these findings, how might language teachers be successful in using music in their classrooms? Results Teaching Experience, Self-Identified Musicality, and Teacher Training Respondents displayed a wide range of professional language teaching experience, at least 3 years and at most 40 years, with an average and median length of 21 years of teaching experience. Participants were then asked whether they self-identify as a musical person, to which 2 selected “not at all”, 6 “a little”, 10 “somewhat”, and 4 “very”. Thus, we see that the majority of respondents consider themselves to be at least “somewhat” musical, with this response and “very” encompassing 64% of responses. It is also noteworthy that the vast majority (over 90%) Kuzman 29 describe themselves as at least “a little” musical, which we must keep in consideration as we discuss the remaining results of this survey. One further question asked whether participants had received any recommendations to use music during their educational training, to which 12 responded “yes”, 7 “no”, and 3 “I can’t remember”. So the majority (63%) of those who could recall had indeed encountered music as a suggested pedagogical tool during their teacher education. However, of these professors, how many actively incorporate music into their language classes, and what are their reasons for doing so? Correlations Between Musicality, Teacher Training, and Music Use Next, a correlational analysis was conducted of answers to the previously-discussed questions “To what extent do you consider yourself a ‘musical person’?”, “Did you encounter any recommendations to use music during your educational training?”, and “How often do you use music in your language courses?” No causal relationship was thought to be possible between self-identified musicality and teacher training recommendations, and so these two variables were not analyzed comparatively. However, both other possibilities were indeed analyzed and displayed the following results: firstly, there appears to be no positive correlation between educational recommendations and frequency of music use among professors. The data showed that among the seven respondents who remembered not encountering recommendations to use music in language teaching, the majority (57%) use music either “often” or “very often” in their language classes. The remaining 43% use music “sometimes”, while no respondents reported “never” using music at all to teach languages. Of the ten respondents who did in fact remember hearing music recommended as a teaching tool in their education, half shared that they use music “often” and half “sometimes”, with no responses of “never” or “very often”. These data demonstrate that those language professors at Middlebury College who responded to this survey Kuzman 30 have majoritarily decided to use music in their language classrooms, independently of whether they were recommended to do so in their education. In terms of the second pair of variables, that of self-identified musicality and frequency of music use, we can recognize a more positive correlation between the two. The most common pair of responses to these two questions was “somewhat” [musicality] and “sometimes” [music use], represented by six participants (27%). These two responses were equivalent in this survey, and thus may suggest a correlation between respondents’ self-reported musicality and their use of music to teach languages. The second-clearest example of this pattern is found in the response pair “very” [musicality] and “often” [music use], which was the case for three respondents (14%). These two responses are not exactly equivalent, as “very” musical was the most affirmative possible response to its question, while “very often” was a further possibility for music use, respectively. However, we can consider these two responses functionally similar, as their commonly-understood definitions are extremely proximal. Similarly, we have the example of the response pair “a little” [musicality] and “sometimes” [music use], equivalent responses which were also represented by three respondents (14%). This displays the result that a majority (54%) of respondents’ self-reported musicality directly or functionally corresponds with their respective use of music in language instruction. This may suggest that a language professor’s personal opinion of their own musicality either influences and/or is correlated with the frequency of their use of music in language teaching. Teaching Style and Approach In order to better understand the underlying pedagogical practices of those professors who responded to this survey, participants were asked to briefly “describe [their] teaching style or approach”. In a word frequency analysis of these responses, by far the most common was Kuzman 31 “communicative”, with fully one half (11 out of 22) of respondents mentioning this teaching approach in their answers. Syarief (2016) defines communicative language teaching (CLT) as an approach which “views language as a socially-embedded phenomenon” (12), as well as centering “interaction and meaning-makings” (ibid.). This author also notes CLT’s focus on the importance of developing communicative and functional competencies in a foreign language (ibid.), all values which strongly support the integration of music as a pedagogical tool. (For further discussion of the communicative approach to language teaching, see also: Littlewood 1981; Savignon 1987). The second most common response mentioned by participants was “student-centered” or “learner-centered”, which combined were reported in 8 out of 22 answers, or by 36% of respondents. The next most common response, “interactive”, was half as common as the former, with four professors (18%) describing their teaching style thusly. And finally, two participants (9%) each mentioned “group work” or “group activities”, or “in context” teaching, respectively. Importantly, all of these above approaches can be considered to align well with the pedagogical approach of employing music in language teaching, and none appear to be mutually exclusive or stand in opposition to this recommendation. After a review of all responses to this question, no other significant patterns were found across multiple respondents, displaying that there is a wide variety of individual teaching styles among these particular language professors. It is striking that fully half of all respondents described their teaching style (at least in part) as communicative, indicating that this specific pedagogical methodology is by far the most common among this sample, as no other comparable or competing method was mentioned more than once. This is most likely in large part due to the era in which most of these professors earned their degrees, as the communicative approach first gained popularity in the 1980s before entering somewhat of a decline in more recent years. Kuzman 32 For a visual representation of the above-mentioned results, please see the word cloud below (Fig. 1.1). Extraneous words and phrases which do not directly describe a teaching style were sorted through and removed, and small typos and omissions of punctuation were edited to improve readability and categorization. Importantly, the responses “student-centered” and “learner-centered” were considered practically identical, and thus were grouped together under the former, more common term. It is important to note that a great number of the further approaches mentioned are also aligned with the practice of musically-integrated language teaching, including but not limited to: “authentic materials”, “experiential”, and “multi-medial”. Fig. 1.1: Word Cloud of Teaching Style and Approach Responses (created with worditout.com) Kuzman 33 Music Use for Specific Levels and Purposes Next, respondents were asked to select whether they introduce music at beginning and/or intermediate and advanced levels of language courses. Results were striking, in that fully 21 out of 22 responding professors answered that they use music in both beginning and intermediate level language classes, representing more than 95% of our sample size. At advanced levels, fewer respondents still rely on music in their language classes, however a very significant number still do so: 18 out of 22, or 82%. When we cross-reference all three possible answers, we see that fully 17 out of 22 professors surveyed (77%) use music at beginning, intermediate, and advanced language levels. These results suggest that of the 22 Middlebury College language professors who responded to this survey, the vast majority employ music as a practical pedagogical tool, regardless of language level. This displays high regard for music in language teaching for learners of all ability levels, expanding upon our previous suggestion to use music at beginning levels in order to introduce and habituate students to their target language’s sounds. We now turn to the question, “For which specific purposes do you employ music in the classroom?”, to which five multiple choice options were provided, with a sixth option for respondents to enter their own responses. These options were: 1) “To improve phonological skills/pronunciation”; 2) “To increase vocabulary acquisition/retention”; 3) “To practice specific grammar points”; 4) “To motivate my students”; 5) “As a cultural learning experience”; and 6) “Other - Please elaborate”. These proposed responses were inspired by patterns found in the above literature review, as well as personal experience and conversations with practicing professionals in the field of language pedagogy. The most common response was that respondents use music as a cultural learning experience, with 19 out of 22 professors (86%) selecting this option. However, nearly the same number (18 out of 22, or 82%) indicated that Kuzman 34 they use music to motivate their students or to practice certain grammar points. The next most common response, selected by 14 out of 22 respondents (64%), was employing music to increase vocabulary learning. The least common provided response was using music to improve phonological and pronunciation skills of students; however, this option was still selected by a majority of respondents (13/22, or 59%). Notably, every one of the 22 professors surveyed use music for at least one of the provided pedagogical reasons, indicating a broad base of rationales which support this practice. Finally, 8 out of 22 participants (36%) chose to enter their own responses which did not correspond to any of the provided options. These included: music as a mnemonic device to help remember patterns in the language; to have fun with students and give them a break and change of pace; analysis of music and video performances; preparation for karaoke social activities; illustration of themes and musical references encountered in class; and listening comprehension practice. Interestingly enough, one respondent said that they use music “to introduce traditional culture”, but did not select the cultural learning experience response. This may indicate that they consider “traditional culture” and “cultural learning” to be different, however if we consider them to be functionally similar, this would then increase the number of option 5 responses to 20 out of 22, or 91%. Importantly, it was found that an overwhelming majority of respondents (19 out of 22, or 86%) use music for at least three distinctly different reasons, while fully half cited five or six reasons for doing so. Judging by these responses, we may conclude that the great majority of these professors utilize music in their language classrooms for a large variety of different purposes, most of which align with the five responses provided in the survey. Between the eight responses entered by participants of their own accord, no clear pattern can be established, which may indicate that Kuzman 35 music is a highly flexible and versatile pedagogical tool which different professors employ in multiple, unique ways. It is telling that almost all of these respondents reported using music for three or more of the suggested reasons, and half of them for five or even six reasons. Also important to note is that with such a small sample size, it is difficult to encounter consistent and statistically significant patterns which may be generalized. And we may also pose the question of whether these professors generally utilize music simply in order to teach linguistic aspects or rather as cultural content in its own right, which was not investigated in this survey. However, these responses do indeed suggest that among language faculty at Middlebury College, music is an extremely widely-used and multi-faceted tool in language classrooms for a wide range of reasons. This therefore supports the argument that music is recognized as a valid and valuable pedagogical tool in the foreign language classroom. Evolution of Music Use in the Foreign Language Classroom and Pedagogical Underpinnings In the following section of the survey, participants were first asked, “How has your use of music evolved over the course of your teaching career?” This question sought to understand individual professors’ personal and pedagogical evolution over time in regards to their use of music, and to identify any common patterns that may exist among them. One respondent did not provide an answer to this specific question, which may have been intentional but could also have been an oversight. And one professor mentioned being newer to teaching and so not having “had much time to evolve”. Of the remaining 20 participants who responded, 5 of them (25%) reported that their use of music really has not changed much “except for incorporating newer materials” or noting that “only the technology has [changed]”, as well as mentioning that “it is maybe more a [teaching] unit now”. However, the remaining 15 professors did indeed recognize Kuzman 36 and report changes in their use of music over time; their answers were thus coded and categorized for comparitive analysis. The most common response to this question was simply that participants use music in their teaching more often now than in the past, with 4 out of 20 (20%) directly mentioning this specific change. Equally as common in these responses were references to cultural learning, with multiple direct mentions of the use of music to teach cultural aspects in language classes. However, of these responses, only two concretely stated that they now use music more to teach cultural aspects; one has done so from the beginning on, while the other simply believes that music aids in understanding “cultural aspects at many levels”. The next most common theme was professors having expanded their musical repertoires over time, with 3 out of 20 (15%) of respondents giving a response along these lines. Two of these answers mentioned expanding beyond solely contemporary music into other genres, while the third spoke of using a “mix and match” approach to find songs that are most appropriate for a variety of students. This has reportedly “helped to increase their in-class engagement and [this professor’s] appreciation of their language-specific needs”, a strong endorsement of appropriate and appreciated music as a way to actively involve and engage students more thoroughly. Three participants (15%) spoke of the practicality of using music with students at varying levels of ability: one mentioned that their music’s “level of lyrical complexity increased” as they began to teach higher levels of ability. In a similar vein, another has “become more likely to use music with older and more advanced students”, and not just beginners and younger learners. A further participant believes that “music helps understand language learning…at many levels”, providing support for their above-mentioned colleagues’ use of music at higher levels. Similarly, one of their fellow respondents mentioned that they now employ music for linguistic teaching Kuzman 37 ends, rather than purely cultural ones. Two participants (10%) mentioned that earlier, they would have students try to understand song lyrics, e.g. by reading them and filling in blanks, but have now ceased to perform this activity, either because this was “not contextualized enough” or “they can do this on their own”. Instead, one now shared that they tend to rather “focus more on the ideas or themes present in the lyrics”. This example demonstrates that perhaps typical musical language learning exercises such as the cloze/fill-in-the-blanks activities cited above are not the most effective in practice in the classroom, and that language teachers could focus more on broader applications such as the linguistic content which music can bring to their students instead. It is advisable to further investigate the exact kinds of activities for which language educators use music in their classrooms, however this was outside the scope of the present survey. No clear patterns can be found between the remaining responses, which nevertheless also contain valuable insight into the teaching practices of those language professors who responded to this survey. One participant shared that their use of music has evolved “organically - based on theme or popular[ity]” over time, thus adapting their music choices to best match their teaching material and current trends. Another respondent has quickly realized the “importance of addressing the…political/social/historical background” of songs, in addition to using them as a tool to capture student interest and teach some grammar and pronunciation. Furthermore, recently this same individual has found that music affords them ways to address “issues of gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, ability, and more”, an extensive range of important and pressing themes in the present-day classroom and world at large. One respondent remarked that they found it more difficult to incorporate music during the pandemic over Zoom, perhaps because of reduced audio quality and latency, suggesting that this format may function best as an Kuzman 38 in-person activity. However, there is not enough data in the present survey to draw any such concrete conclusions. Finally, a certain professor noted that although they are not a very musical person, they have discovered that “this is no impediment to enjoying music with [their] students and sharing [their] passions!” This displays a strong support for music as a tool for any and all language educators to use, not just those who consider themselves to be very musical individuals. As responses to the question “What are some pedagogical underpinnings of your use of music?”, three predetermined and one text-entry options were provided: 1) “Affective - It may improve students' motivation, engagement and comfort, reduce anxiety, etc.”; 2) “Linguistic - It may enhance students' language skills such as pronunciation, vocabulary, etc.”; 3) “Cultural - It may increase students' cross-cultural awareness and knowledge”; and 4) “Other - Please elaborate”. Of these options, the highest number of respondents (21 of 22, or 95%) selected cultural reasons for their underlying pedagogy in using music, followed closely by affective and linguistic reasons, each of which received 19 responses (86% of respondents). These results are quite significant, in that the vast majority of these professors’ musical language teaching pedagogies are supported by all three of these rationales. This indicates very strong experiential evidence for the use of music in language teaching among the professors surveyed. Only three participants selected Option 4, indicating that the vast majority found the three provided options adequate to describe their pedagogical reasons for using music. However, one of these additional responses made reference to cultural knowledge “from different eras and in different countries”, apparently further specifying Option 3 (which this respondent also selected). Another emphasized their creative use of “mostly non-didacticized” music, which they select from their own repertoire and not from textbooks, in addition to selecting all three of the given options. And the third and final respondent was the only one not to select Option 3, offering the Kuzman 39 viewpoint that it is difficult for them to choose songs which they “can accurately claim represent the culture”. This professor believes that “too often songs are used to display ‘culture’, when they are really displaying just one artist's intentions with that one work”. Furthermore, they stated that they do not have the time or the training to survey the vast amount of music necessary to make a valid claim about culture. This is an important caveat to note: we must be prudent when making claims about the cultural content of our chosen songs, and be careful not to overgeneralize their cultural representations. However, we can and should still consider songs to be important cultural artifacts which allow learners to come into contact with the cultures of their target languages, and not shy away from using music as a cultural learning experience. Effects on Student Learning Attributed to Music The vast majority of professors surveyed (21 of 22, or 95%) shared that they have noticed positive effects on their students’ learning which they attribute to music, while only one (5%) saw “no noticeable difference”, and none noticed any negative effects. However, of the 21 who chose the “positive effects” option, two did not elaborate on this choice, leaving us with 19 responses to this option which may be analyzed. The most common theme found among responses to this question was that of musical interest being sparked among students and continuing even outside of class time, with 9 of the 19 respondents who provided an answer (47%) mentioning this. Importantly, multiple participants stressed the importance of students’ listening to music regularly and on their own in order to create these positive effects, suggesting that if music is limited only to classroom contact, it does not have the same volume of positive effects. On a similar note, two respondents emphasized the importance of creating playlists in our target languages, which students can then take with them and listen to on their own time, fostering connections with the language outside of class. Kuzman 40 The next most common theme encountered is that music has effectively increased student motivation, which was mentioned by six professors (32%) in their responses. This aligns with the findings in the above literature review, which determined that music is indeed a highly effective motivator in language learning settings, in addition to supporting our initial hypothesis. Another commonality between responses is that of the cultural impact of music in language education. Four respondents (21%) brought up the cultural aspects of musical language learning, stating that their students “enjoy the cultural encounter”, “feel” culture in addition to just hearing it, and become “more emotionally connected to the language and culture”. These are important and impactful points which emphasize the cultural significance that music can have in the language classroom, helping to connect students with cultures other than their own. Some further positive effects of incorporating music noticed by individual professors may be categorized along two lines. First were positive emotional effects, which included: improved student engagement; a “great atmosphere”; emotional responses to music; student relaxation; and increased curiosity. These effects support the similar benefits discussed in the literature review above under the category “Affective and Emotional Benefits”, providing reallife data from current practicing professors who have seen such positive impacts on their own students. Secondly, respondents recounted multiple more tangible linguistic benefits, such as: higher retention [of information]; easier memorization and recall of language “chunks”; and students’ observing the real-life practicality of linguistic forms. These findings correspond very closely to the results discussed above in the section “Linguistic Benefits”, adding further credence to the aforementioned research by bringing in the perspectives of active language professors. However, an important question that remains is how exactly these professors determined such results, whether by their own anecdotal experience and/or concrete and testable Kuzman 41 results which they methodically observe in their classrooms. This should be further investigated in future research in order to provide more concrete, quantitative research regarding these results. Professor Opinions and Suggestions on Music in Language Curricula In this section of the survey, the intention was to gather information on respondents’ opinions of current language curricula and whether or not they feel that they have enough possibilities to incorporate music within them. To this end, participants were asked: “Do you wish that curricula afforded you more opportunities to teach languages through music?”, to which no one responded “Not at all”, one person (5%) each selected “Not really” or “Absolutely”, and 10 respondents (45%) each chose either “I’m neutral” or “I’d like that”. These responses demonstrate that the professors surveyed tend not to have highly polarized opinions on this subject, skewing more towards the neutral middle in their responses. If we group together neutral and negative answers, we then see that the number of participants who did not actively express a desire for more chances to incorporate music in language curricula is exactly equal to those who would in fact appreciate such opportunities. However, when we do not consider neutral responses, as they represent the midpoint of possible answers, it becomes clear that there are many more affirmative responses to this question than negatory (11 as opposed to 1). These results display that of the professors surveyed, only one would actively not like curricula to afford more chances to teach through music, and those who are neutral on the issue are slightly fewer than those who would indeed appreciate this opportunity. Thereafter, respondents were asked the open-ended question, “If you had the option of including more music in curricula, how would you employ music?” Five participants did not elect to answer this question, and so only 17 responses were recorded, of which 11 shared their ideas for how they would utilize music more in their language teaching. However, six stated that Kuzman 42 they would not, either because they already have enough liberty to do so (four responses, or 24%), because they are “not a musicologist”, or because they see that music only “engages like 1/3 of the learners, but not all of them…[and] is just one tool in a toolkit”. These are important caveats to note, as multiple professors at this university level reported having the autonomy to use music to the level they desire, which we can presume is closely linked to the neutral responses in the question above. However, importantly the great majority still reported diverse ways in which they would use music if their language curricula afforded them more such opportunities, displaying that not all professors at this level feel the freedom to do so already. Three respondents (18%) mentioned a desire to incorporate more rap or popular music into their classes. Rap was cited because “it reflects and expresses the cultural and social complexity of certain issues better than other materials can” and includes storytelling elements which can “replace written texts” in a more interactive way. One participant proposed popular music because of positive personal experience, expressing a strong desire to work with music not necessarily relevant to the current topics in class, for which there is not much time now. Two respondents (12%) said that they would use music more often and earlier on as a tool to improve pronunciation at beginning levels, mirroring previously discussed findings that music is highly effective in teaching pronunciation. At higher levels, participants would teach cultural issues and content through song, further strengthening the cultural argument for musical language education discussed above in multiple sections. Finally, five professors shared opinions that were not easily categorized, but merit mention nonetheless. One has considered teaching a J-Term class based around folk music, which would (presumably) be a fully music-centered language class that would be worthy of further investigation. This begs the question of whether such a course would primarily be a Kuzman 43 language-centered class or more strongly focused on the folk culture in this language. Another would use music “as an object to foster conversation and start a task”, incorporating music in order to begin dialogue in a foreign language and get students talking. Someone else would prefer to assign music tasks as homework for students to do in their free time, as they “can take longer than other exercises” in the classroom. And two professors suggested various interactive, music-based activities for classrooms, for example: listening sessions and discussions about music where guests could perform and share their favorite music; or reenacting and interpreting songs in their own words, writing about their meaning, and eventually choosing their own songs and presenting their findings to the class. These are all insightful and important ideas and suggestions which we would do well to keep in mind when discussing foreign language curricula and class design. Professor Recommendations for Music Use in the Language Classroom To conclude the survey, professors were asked, “What advice would you give to an aspiring language teacher on how best to use music in the classroom?”, which yielded a wide variety of valuable advice for those of us looking to become better language educators through the use of music. One person did not enter a response, leaving us with a sample size of 21 for this question. The most common theme that came up (from six participants, or 29%) was the importance of not foisting our own musical tastes upon learners, but rather allowing them to contribute their own input to musical selection and making sure to select songs that are relevant and interesting to them. However, on the other hand, one professor did stress the importance of choosing music that “‘speaks’ to you most loudly”, reminding us of the importance of selecting music which we also connect with, and another similarly said to “pick what you like”. Two respondents (10%) mentioned using music to teach phonetics and pronunciation, further Kuzman 44 strengthening previous arguments to this effect. The same number of participants (2 of 21) recommended that we not “overdo it”, and that “a little goes a long way”, warning us against the danger of too much music use. However, both of these professors also did support using music in language classrooms, with one saying that we should “definitely use songs to improve mood”, alluding more to affective benefits. Along similar lines, another respondent mentioned that music “creates [a] fun…[and] very focused atmosphere”, mentioning the positive changes in mood which music can bring about, as discussed above. Among these responses, two professors (10%) suggested playing music at the beginning of class, setting the tone for the lesson to come and in order to “ritualize the use of music”, as one other put it. Similarly, another suggested that we “get them used to singing from the very first language class in 101”, and someone else recommended that we “go for it and sing loudly even if you're bad at it so students know that it's OK :)” These responses all espouse a culture of musical learning and sharing from our very first contact with a language class, normalizing and integrating music as a fundamental and essential part of our lessons. In terms of the pedagogical practice of musical activities, two further participants spoke to the importance of “the structure and emphasis of the activity” and “creating a pedagogical activity around it”. These professors make the important point that activities involving music must be carefully and mindfully created, warning us against simply playing a song for a class without any other context surrounding it. Similarly, someone else discussed not using music “as a disconnected distraction”, instead proposing that we “go deep” into our musical content. Thus, we encounter here various recommendations for using music in language classrooms, with a focus on the importance of consistent and contemplative pedagogical practices. Kuzman 45 The remaining responses were more resistant to classification, however still contain valuable suggestions. One professor recommended frequent consultation with teaching colleagues, paying attention to professional organizations and attending conferences, and keeping a list of songs and databases we have used in the past. Another suggested searching lyrics databases in order to find “the linguistic structures and functions you are teaching that day”, an insightful way to link class content directly to song lyrics. A different participant proposed using a tool such as music videos, which “allows students to engage on multiple levels”, offering multiple means of access to learners of different kinds and abilities. A further respondent recommended repeatedly listening to the same audio, especially at beginning levels, as they “have found that students absorb more through repetition”, an important insight into students’ musical learning. This mirrors suggestions encountered in the above literature review to incorporate repetition of music with beginners in order to increase sound discrimination abilities. One participant noted that “you can add grammatical exercises, but for me it's never the main point”, supporting the perspective that music is a way to teach much more than just grammar. A different respondent mentioned the importance of choosing songs with “not too many swear words”, though acknowledging that some are indeed acceptable as students do need to learn them, an oft-forgotten or willfully ignored fact in traditional language classrooms. However, the clearest and most direct recommendation was the most succinct and pointed of all: “Do it!” Synthesis and Connections with the Literature In the above survey results and discussion, we have encountered a very wide range of personal pedagogical practices and approaches, many of which directly support the initial hypotheses of this thesis. To reiterate, these are: that music as a pedagogical tool effectively Kuzman 46 increases student motivation, as well as positively impacts concrete linguistic learning outcomes. Both of these have been supported by the previous literature review, and are now lent further credence by the opinions of the language professors collected in this survey. Notably, multiple respondents mentioned that they have indeed noticed increases in their students’ motivation and engagement in class, in addition to other heightened affective benefits such as emotional responses to music. This represents an important overlap between the literature and this survey in terms of multiple affective aspects in the language classroom, which may be successfully improved through the use of music. Furthermore, positive linguistic benefits have also been observed by these professors, including but not limited to: improved retention, memorization abilities, and recall, all three of which were indeed found in the former literature review as well. One final noteworthy finding which was not proposed in the initial hypotheses is the potential for music to significantly improve students’ foreign language pronunciation, especially at beginning levels. Both authors reviewed in the literature and survey participants cite the efficacy of repeated musical exposure to positively impact pronunciation, especially at beginning levels. These responses mirror and solidly support similar findings in the literature review which show that music is efficacious at positively impacting student performance in class. Thus, we can conclude that all of the particular points above are underpinned by both academic research as well as practicing language professionals’ personal experience with their language students. One further pattern which appears significant is the recommendation of multiple survey respondents that we need not be musical professionals or consider ourselves highly musical people in order to successfully employ music with our students. Multiple professors who were surveyed referenced this suggestion, with one encouraging us to sing in class (even if badly) in Kuzman 47 order to convey to students the acceptability of doing so. This sentiment was echoed by another participant, who was happy to have discovered that their self-described non-musicality was not an impediment to having a positive experience using music with their students. Thus, we can see that employing music in the classroom can truly be a positive experience for teachers of all described musicality levels, and that they need not be professionals or have considerable musical experience to do so. This, I believe, is the most important and impactful recommendation to emerge from this survey: all language educators can, and should, successfully incorporate music into their classrooms in order to enjoy the multiple benefits of doing so. Conclusions, Limitations, and Suggestions for Further Research The goal of this thesis has been to successfully synthesize and bring together a variety of valuable sources from a wide range of disciplines, providing concrete research examples as well as personal and practical recommendations from experienced language professionals. We have taken a journey through the fields of pedagogy, neuroscience, and musical and linguistic theory, which on the whole decidedly point to the practicality and effectiveness of combining music and language education. The experiences and encouragement from the professors surveyed further strengthen the conviction that this is indeed both a highly effective as well as enjoyable manner of teaching and learning languages. We can confidently say that both initial hypotheses have been soundly supported by solid and varied evidence, and that in fact we have discovered considerably further benefits which may come from this approach as well. In other words, music is indeed a highly effective pedagogical tool when applied to language education, increasing student motivation and positively affecting students’ emotional state. Neurologically, music and language are processed in the same brain areas, and so we may consider that combining these two domains serves to support the cognitive processing of both. Additionally, music is Kuzman 48 considerably efficacious in concretely improving a large variety of foundational linguistic skills, which are essential in learning to speak and understand a foreign language well. However, it must be acknowledged that this study has some important limitations as well. The survey sample size was notably small, and thus its results cannot be overgeneralized or considered overly significant. Furthermore, it must be recognized that these professors teach at a small, elite liberal arts college in the USA, and thus do not constitute a representative sample of language educators around the world or even the country. It may also have been a vacuous oversight not to directly ask respondents in which specific ways and with which activities they employ music in their language teaching, which should be investigated in future research. This would allow us to more concretely and productively compare the specific manners in which professors utilize music in their language classrooms. A cursory overview of published research on the topic reveals a great many such reports in which language educators describe in detail their particular pedagogical practices regarding music-based activities; however, these rather anecdotal accounts were outside the purview of the current research, and may best be investigated in further studies. It would be a considerable and valuable task to perform a comprehensive study of such resources and synthesize them in a productive manner which affords language educators a varied “toolbox” of practical activities that they may utilize in their teaching. Such a survey could then be compared to the scientific findings reviewed in the present study in order to determine the most efficacious, as well as intuitive, resources for practicing language educators to design and use. In the future, more rigorous and detailed applied pedagogical studies should be conducted which put these and further hypotheses to the test in longer-term experiments with language classes. It is currently difficult to ascertain from existing studies the specifics of music use in Kuzman 49 terms of content areas and activities, and so it would be beneficial to study such precise questions more consistently in order to facilitate analysis and comparison. It would be advisable to gather more detailed data on particular music use and pedagogical activities, which would be invaluable information in order to measure certain methodologies’ effectiveness. Such rigorous research could help us to better put into practice the theoretical knowledge which has been gleaned from the current study, and to determine which particular strategies and advice seem to be the most effective and enjoyable for students. Furthermore, it would be important to study whether these findings apply to all languages equally, especially those which already are taught primarily through audio-aural means, and those which do not have a large repertoire of recorded musical materials readily available. In conclusion, music indeed appears to be a highly effective and enjoyable tool with which to teach language, with extensive practical applications beyond those proposed in our initial hypotheses. We may say that many of the traditional woes associated with language education could be remedied in large part by the addition of more, pedagogically sound music practices. Without overly pontificating, this is a very personally important subject, and the goal of this thesis is to communicate and support this passion in a very clear, concrete, and convincing manner. This project has only served to further strengthen the conviction that musical language education is an extremely valid and valuable pedagogical tool, which we would do well to integrate into our teaching practices. Hopefully this work has exposed the reader to a wide range of new insights which spark new personal and professional curiosity, as well as a desire to implement this method with our students. In parting, let us reflect upon and appreciate the very wide range of academic, scientific, pedagogical, and practical knowledge synthesized in the current study. Together, this considerable collection of knowledge clearly displays that music Kuzman 50 can, and indeed should, be used as a principally important instrument in the field of language education. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor and first reader for this thesis, Professor Bettina Matthias. Professor Matthias was an extremely active, engaged, and endlessly supportive advisor for this project, and has strongly supported me with these hypotheses for many years. Her very broad knowledge and expertise of both foreign languages as well as the use of the arts to teach them were very valuable throughout this whole process. She was an especially responsive and dedicated advisor, contributing much of her own time to assist with this thesis each and every week over the course of the semester and even before. Vielen, vielen Dank Bettina, aus tiefstem Herzen, dank Dir ist diese Thesis überhaupt möglich. Professor Shawna Shapiro deserves special mention as my academic advisor, third thesis reader, and most important supporting faculty member during the long and arduous process of becoming an independent scholar in linguistics. Professor Shapiro has wholeheartedly supported me in this independent path over the last few years, always providing personal and professional support whenever needed. She was also instrumental in providing feedback on the survey questions for this study, taking time during her sabbatical to offer valuable insight which considerably improved the quality of the questions and data collected. Thank you so much Shawna, I could never have completed this major without all of your help and encouragement. Professor Florence Feiereisen merits my sincere gratitude for introducing me to the academic study of linguistics, showing me that it can be so much more than just grammar analysis and syntax trees. Her personal teaching pedagogy and methods remain an inspiration Kuzman 51 and motivation for me to improve my own, as she always brings out only the best from her students, making learning truly enjoyable. Professor Feiereisen also kindly and skillfully advised the independent study which supported this thesis over the course of the previous semester, and contributed valuable research material to this project. Danke Florence, dank Dir habe ich schließlich Linguistik studiert. Professor Per Urlaub must be gratefully acknowledged for graciously offering to be the second thesis reader as well as advise the previous semester’s independent study. Professor Urlaub contributed extremely helpful and detailed input concerning the procedures and structure of this thesis, which I highly appreciate. His wide range of expertise in second language acquisition is very gratefully accepted and valuable in this entire thesis process. Vielen Dank Per, ich weiß es, Deine Hilfe zu schätzen. I would also like to express my appreciation for the contributions of Ms. Diane DeBella of the Middlebury College CTLR, whose expertise in all formatting and citing matters were indispensable during this thesis project. When even my millennial googling skills were ultimately unsuccessful in locating specific and necessary information, I turned to Ms. DeBella multiple times, and she promptly and patiently proposed possible solutions to my problems. Thank you very much for your skills, kindness, and patience with me during this work. Finally, I would like to respectfully recognize the contributions of Mr. John Hoffman, Jr. for his shrewd and insightful comments regarding language use in this thesis. Mr. Hoffman also warrants particular gratitude as my most senior-ranking active acquaintance, having first had the privilege of meeting pre-grade school. Thanks so much for your friendship and input John, this thesis is indubitably a much more interesting read as a direct and indisputable result of your astute observations. Kuzman 52 Works Cited Ajibade, Yetunde and Kate Ndububa. “Effects of Word Games, Culturally Relevant Songs, and Stories on Students' Motivation in a Nigerian English Language Class.” TESL Canada Journal 26 (2008): 27-48. ERIC. Web. 1 Apr. 2021. Blackwood, D. H. R., and W. J. Muir. "Cognitive Brain Potentials and Their Application." British Journal of Psychiatry 157.S9 (1990): 96-101. Cambridge Core. Web. 31 Mar. 2021. Brown, Steven, et al. "Music and Language Side by Side in the Brain: A Pet Study of the Generation of Melodies and Sentences." European Journal of Neuroscience 23.10 (2006): 2791-2803. ResearchGate. Web. 5 Mar. 2021. Brown, Steven, et al. “Passive Music Listening Spontaneously Engages Limbic and Paralimbic Systems.” NeuroReport 15 (2004): 2033-2037. BrainMusic. Web. 20 Apr. 2021. DiEdwardo, MaryAnn P. "Pairing Linguistic and Music Intelligences." Kappa Delta Pi Record 41.3 (2005): 128-130. ResearchGate. Web. 5 Mar. 2021. Dolean, Dacian Dorin. “The Effects of Teaching Songs during Foreign Language Classes on Students’ Foreign Language Anxiety.” Language Teaching Research, 20.5, (2016): 638– 653. SAGE. Web. 4. Apr. 2021. Dolean, Dorin Dacian, and Ioan Dolean. "The Impact of Teaching Songs on Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety." Philologica Jassyensia 10.19 (2014): 513-518. Semantic Scholar. Web. 4. Apr. 2021. Fagerland, Rhoda. "Can Music Be Used Effectively To Teach Grammar?" A Journal for Minnesota and Wisconsin Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages 41 (2006): 41-58. ResearchGate. Web. 12 Apr. 2021. Kuzman 53 Failoni, Judith W. "Music as Means to Enhance Cultural Awareness and Literacy in the Foreign Language Classroom." Mid-Atlantic Journal of Foreign Language Pedagogy 1 (1993): 97-108. ERIC. Web. 5 Mar. 2021. Farmand, Zahra and Behzad Pourgharib. “The Effect of English Songs on English Learners Pronunciation.” International Journal of Basic Sciences & Applied Research 2.9 (2013): 840-846. ResearchGate. Web. 4 Apr. 2021. Fedorenko, Evelina, et al. "Structural Integration in Language and Music: Evidence for a Shared System." Memory & Cognition 37.1 (2009): 1-9. ResearchGate. Web. 7 Mar. 2021. Fisher, Douglas P. “Early Language Learning With and Without Music.” Reading Horizons 42 (2001): 39-49. ResearchGate. Web. 11 Apr. 2021. Fonseca-Mora, Carmen. "Foreign Language Acquisition and Melody Singing." ELT journal 54.2 (2000): 146-152. ResearchGate. Web. 29 Mar. 2021. Israel, Hilda F. “Language Learning Enhanced by Music and Song.” Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal (2013): 1360-1366. ResearchGate. Web. 4 Apr. 2021. Jeffries, Keith, et al. “Words in Melody: An H215O PET Study of Brain Activation During Singing and Speaking.” NeuroReport 14 (2003): 749-754. BrainMusic. Web. 20 Apr. 2021. Kao, Tung-an, and Rebecca L. Oxford. "Learning Language through Music: A Strategy for Building Inspiration and Motivation." System 43 (2014): 114-120. ScienceDirect. Web. 4 Apr. 2021. Kara, Zehra, and Aynur Aksel. “The Effectiveness of Music in Grammar Teaching on the Motivation and Success of the Students at Preparatory School at Uludağ University.” Kuzman 54 Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 106 (2013): 2739-2745. Semantic Scholar. Web. 12. Apr. 2021. Koelsch, Stefan, et al. "Music, Language and Meaning: Brain Signatures of Semantic Processing." Nature Neuroscience 7.3 (2004): 302-307. ResearchGate. Web. 4 Mar. 2021. Krashen, Stephen D. Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. Pergamon, 1982. Print. Lems, Kristin. "New Ideas for Teaching English Using Songs and Music." English Teaching Forum. 56.1 (2018): 14-21. US Department of State. ERIC. Web. 8 Mar. 2021. Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. MIT, 1983. Print. Li, Xiangming, and Manny Brand. “Effectiveness of Music on Vocabulary Acquisition, Language Usage, and Meaning for Mainland Chinese ESL Learners.” Contributions to Music Education 36 (2009): 73-84. Semantic Scholar. Web. 8. Apr. 2021. Littlewood, William. Communicative Language Teaching: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press, 1981. Print. Maess, Burkhard, et al. “Musical syntax is processed in Broca's area: an MEG study.” Nature Neuroscience 4.5 (2001): 540-545. ResearchGate. Web. 22 Mar. 2021. Mobbs, Andrew, and Melinda Cuyul. "Listen to the Music: Using Songs in Listening and Speaking Classes." English Teaching Forum. 56.1 (2018): 22-29. US Department of State. ERIC. Web. 13 Mar. 2021. Moradi, Fereshteh, and Mohsen Shahrokhi. "The Effect of Listening to Music on Iranian Children's Segmental and Suprasegmental Pronunciation." English Language Teaching 7.6 (2014): 128-142. ResearchGate. Web. 5 Apr. 2021. Kuzman 55 Parsons, L. et al. “The Brain Basis of Piano Performance.” Neuropsychologia 43 (2005): 199215. ResearchGate. Web. 18. Apr. 2021. Patel, Aniruddh D. "Language, Music, Syntax and the Brain." Nature Neuroscience 6.7 (2003): 674-681. Springer Nature. Web. 13 Mar. 2021. Patel, Aniruddh D., et al. "Processing Syntactic Relations in Language and Music: An Eventrelated Potential Study." Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 10.6 (1998): 717-733. ResearchGate. Web. 14 Mar. 2021. Salcedo, Claudia S. “The Effects Of Songs In The Foreign Language Classroom On Text Recall, Delayed Text Recall And Involuntary Mental Rehearsal.” Journal of College Teaching & Learning 7 (2010): 19-30. Clute Institute. Web. 8 Apr. 2021. Savignon, Sandra J. "Communicative Language Teaching." Theory Into Practice 26.4 (1987): 235-242. JSTOR. Web. 27 Apr. 2021 Schön, Daniele, et al. “Songs as an Aid for Language Acquisition.” Cognition 106 (2008): 975983. ResearchGate. Web. 11 Apr. 2021. Staum, Myra J. “The Use of Music to Teach Foreign Language.” Contributions to Music Education 12 (1985): 31–41. ResearchGate. Web. 11 Apr. 2021. Swain, Joseph P. Musical Languages. Norton, 1997. Print. Swaminathan, Swathi, and Jini K. Gopinath. “Music Training and Second-Language English Comprehension and Vocabulary Skills in Indian Children.” Psychological Studies 58 (2013): 164-170. ResearchGate. Web. 8 Apr. 2021. Syarief, Kustiwan. “Communicative Language Teaching: Exploring Theoretical Foundations and Practical Challenges.” Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan 12 (2016): 1-14. ResearchGate. Web. 27 Apr. 2021.