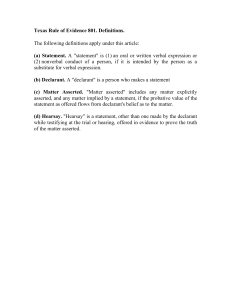

HEARSAY EVIDENCE This is a written or oral statement tendered in order to prove the truth of the matter stated and made by a person who was not a party to the case and was not called a witness. Rationale for the exclusion of hearsay Hearsay evidence is generally inadmissible because evidence is preferable when it is given orally, on oath and is subject to cross examination. Further, hearsay evidence is problematic because the court cannot observe the demeanor of the declarant (the person who made the original statement). It also argued that hearsay evidence is secondary evidence and is therefore not the best evidence. However this view has been rejected, See Vulcan Rubber Works (Pty) Ltd v SAR & H 1958 (3) SA 285 (A). COMMON LAW EXCEPTION TO THE HEARSAY RULE There are six statements by deceased persons that are included in the exceptions. These are statements against interest, statements in the course of duty, statements in the case of murder or culpable homicide, statements concerning pedigree, statements as to public and general rights, and statements as to the contents of wills by testators. STATEMENTS AGAINST INTEREST A statement by a deceased person whether oral or written was admissible as evidence if it was to his knowledge against his pecuniary or proprietary interest at the time it was made. The rationale for this exception is that a man is unlikely to make a false statement when it is against his interest. There were requirements that had to be met 1. The declarant must have died 2. The statement must have been against the proprietary interest of the declarant at the time of making it. 3. The declarant must have known that the statement was against his interests 4. The declarant must have personal knowledge of the fact stated STATEMENTS IN THE COURSE OF DUTY Oral or written statements made by a deceased person are admissible to prove the truth of the contents if made as a result of a duty to record or report contemporaneously and if made without a motive to misrepresent. See Price v Earl of Torrington and Nolan v Barnard (both Shwikkard page 267) DYING DECLARATIONS IN CASES OF MURDER OR CULPABLE HOMICIDE The rationale behind this exception is that no person would wish to be untruthful just prior to his death. The requirements are that 1. The declarant must have died 2. Declarations are accepted only in cases of murder or culpable homicide. They are accepted to prove how the deceased met his death and as such they can be used in favour of the accused where the statements exonerating him, (See for example R v Scaife where the deceased said he would not have been struck had he not provoked the accused). 3. The declarant must have had a settled hopeless expectation of death. This means that the deceased must have given up all hope of recovering; however it does not mean that the declarant must have died immediately thereafter. Where one later entertained hopes of leaving this does not affect the admissibility of the statement. See R v Nzobi where the statement was excluded because the deceased said he was weak and did not think he was going to survive. 4. The declarant must have been a competent witness at the time of making the statement. This means that an individual who because of one reason or another lacked capacity would not make an admissible statement 5. The statement must be complete. If the statement is incomplete because of supervening death or unconsciousness it would be inadmissible because it is impossible to speculate what the deceased would have said See R v Heine, were the accused was charged with murdering one Dora Van Breda by performing an illegal abortion. Two days before her death a magistrate recorded a statement from her stating that she was going to die (See shwikkard page 268) STATEMENTS CONCERNING PEDIGREE Declarations as to pedigree may be admissible as evidence. They must relate to matters actually in issue and the declarant must be a blood relation of the person whose pedigree is in issue. The common law pedigree declarations are to be found in family bibles, which may set out the family genealogy. The requirements for admission were as follows; 1. The declarant must have died 2. The declarant must have been a blood relation (a spouse of a blood relation) of the person whose lineage is in dispute and the relationship must also be a legitimate one 3. The declaration must have been made before the dispute arose STATEMENTS AS TO PUBLIC AND GENERAL RIGHTS A general right is a right that affects a class of persons e.g. grazing rights gained by immemorial use. The requirements for admission were as follows; 1. The declarant must have died 2. The declaration should deal with the disputed existence of a public or general right. See Du Toi v Lydenburg Municipality, this concerned a dispute as to the boundary of the town and an old resident had pointed them to his son. 3. The declaration must have been made before the dispute arose. The admissibility of the statement will not be affected if it was made to cover some future contingencies. 4. The declarant must have been qualified to speak. This means that only a person who has an interest in the right is competent to speak. STATEMENTS BY TESTATORS AS TO THE CONTENTS OF THEIR WILLS SPONTANEOUSS EXCLAMATIONS Oral or written statements by a deceased testator were admissible to prove the contents of the deceased testator are admissible to prove the contents of the will if made after its execution. The declaration is admissible to prove the execution of the will, its alteration or destruction animo revocandi. SPONTANEOUS EXCLAMATIONS If a sudden event had assumed such intensity and pressure that the utterances can safely be regarded as a true reflection of what was actually happening then it ought to be admitted. This does not require the absence of the declarant as statement made during the events in question carry more weight than the same statements being repeated in court by the same person who would have now composed themselves and will not be under any nervous excitement. Startling occurrence There must have been an occurrence startling enough to produce a stress of nervous excitement. Typical examples are assaults, collisions, explosions or even a robbery. There is no closed list of what constitutes a startling occurrence and as such it’s a case by case approach. Spontaneity It is required that the statement should have been made while the stress was still so operative upon the speaker that his reflective powers may be assumed to have been in abeyance. See S v Qolo (lo tsotsi) Shwikkard page 270-71. No reconstruction of past events The statement must not amount to a reconstruction of a past event. Narrative parts excluded Purely narrative matter will be excluded from a spontaneous exclamation. The rationale of this rule is also obvious, any narration is a strong indication that reflective powers were not in abeyance; that the declarant had sufficient time to think or reason and that the statement was therefore not made spontaneously. The criminal procedure and evidence Act 253 Hearsay evidence (1) No evidence which is of the nature of hearsay evidence shall be admissible in any case in which such evidence would be inadmissible in any similar case depending in the Supreme Court of Judicature in England. (2) When evidence of a statement, oral or written, made in the ordinary course of duty, contemporaneously with the facts stated and without motive to misrepresent, would be admissible in the Supreme Court of Judicature in England if the person who made the statement were dead, such evidence shall be admissible in any criminal proceedings if the person who made the statement is dead or unfit by reason of his bodily or mental condition to attend as a witness or cannot with reasonable diligence be identified or found or brought before the court. [Subsection amended by section 28 of Act 9 of 2006.] (3) The court may, in deciding whether or not the person in question— (a) is unfit to attend as a witness, act on a certificate purporting to be a certificate of a medical practitioner; (b) is dead or cannot with reasonable diligence be identified or found or brought before the court, act on evidence submitted by way of affidavit. 254 Admissibility of dying declarations (1) A declaration made by any deceased person upon the apprehension of death shall be admissible or inadmissible in evidence in every case in which such declaration would be admissible or inadmissible in any similar case depending in the Supreme Court of Judicature in England. (2) When it is made to appear to the satisfaction of any magistrate that any person is dangerously ill and, in the opinion of a medical practitioner, not likely to recover from such illness and is able and willing to give material information relating to any offence or to any person accused of any offence, and it is not practicable to examine in accordance with any other provision of this Act the person so being ill, it shall be lawful for the said magistrate to take in writing the statement on oath of such person. (3) The magistrate taking a statement in terms of subsection (2) shall sign it and set out his reason for taking the same, the date and place of taking it and the names of the persons, if any, present at the time. (4) If afterwards, upon the trial of any offender or offence to which the same may relate, the person who made a statement taken in terms of subsection (2) is proved to be dead, or if it is proved that there is no reasonable probability that such person will ever be able to travel or give evidence, it shall be lawful to read such statement in evidence either for or against the accused without further proof thereof— (a) if the same purports to be signed by the magistrate by or before whom it purports to be taken; and (b) if it is proved to the satisfaction of the court that reasonable notice of the intention to take such statement has been served upon the person, whether prosecutor or accused, against whom it is proposed to be read in evidence and that such person or his legal representative had or might have had, if he had chosen to be present, full opportunity of cross-examining the person who made the same. 255 Admissibility in criminal cases of evidence of absent witnesses in certain circumstances (1) The evidence of any witness— (a) given at a former criminal trial of an accused on the same or a different charge and recorded in a document purporting— (i) to be a transcript of the original record of the said evidence; and (ii) to have been certified as correct under the hand of the person who transcribed it; or (b) whose deposition has been verified in terms of section 115A; shall, subject to subsection (2), be admissible in evidence on the trial of the accused for any offence. (2) The evidence of a witness referred to in subsection (1) shall not be admissible unless— (a) it is proved on oath to the satisfaction of the court that the witness— (i) is dead or is incapable of giving evidence, or that he or she is too ill to attend; or (ii) is kept away from the trial by the means and contrivance of the accused; or (iii) cannot be found after diligent search, or cannot be compelled to attend; or (iv) is an expert witness whose evidence is given in his or her capacity as an expert witness, and that the nature of the witness’s professional commitments is such as to render it impossible to secure his or her attendance at the trial on any given day; and that the evidence is the same that was given at the previous criminal trial or at the conference referred to in section 115A, as the case may be, without any alteration; and (b) it appears on the record or is proved to the satisfaction of the court that the accused, personally or by his or her legal representative, had a full opportunity of cross-examining the witness, even if the accused or his or her legal representative, did not avail himself or herself of that opportunity. (3) Where is proved on oath to the satisfaction of the court that any witness, other than one whose deposition was verified as mentioned in subsection (1)(b)— (a) is dead or incapable of giving evidence, or is too ill, to attend; or (b) has been kept away from the trial by the means and contrivance of the accused; or (c) cannot be found after diligent search or cannot be compelled to attend; or (d) is an expert witness whose evidence is given in his or her capacity as an expert witness, and that the nature of the witness’s professional commitments is such as to render it impossible to secure his or her attendance at the trial on any given day; the evidence of such witness may, at the discretion of the court, be admissible in evidence on the trial of the accused for any offence.