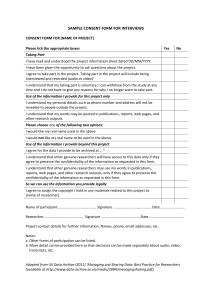

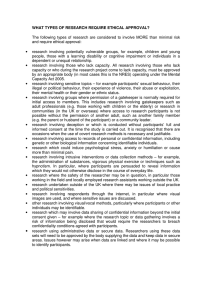

Ahmed Abelhakim Hachelaf______Master Program / Research Integrity Spring 2020 Summary of Research Miscondut from Online Training and other Insights The following summary is compiled from: Helene Lake-Bullock, Marianne M. Elliott, MS, CIP Applied Research Ethics, LLC and the University of Kentucky and is part of the Mandatory Research Training required from researchers at Syracuse University and the International University of Virginia Three Main Research Misconduct I want you to pay attention to: FABRICATION "Fabrication is making up data or results and recording or reporting them" (OSTP 2000, p. 4). Fabrication often involves creating fake data to fit a hypothesis. Fabrication could include creating fictional tables, graphs, or figures that are placed in manuscripts, grant applications, or poster presentations. Unfortunately, fabricated data have contaminated the research literature in many fields, including in physics with Jan Hendrik Schön (Reich 2009) and in psychology with Diederik Stapel (Enserink 2012). Schön was employed by Bell Labs, but he was dismissed after an internal committee found that he had committed numerous instances of research misconduct, including fabricating entire data sets. Stapel was a social psychologist and his misconduct included "the manipulation of data and complete fabrication of entire experiments" (Verfaellie and McGwin 2011). FALSIFICATION "Falsification is manipulating research materials, equipment, or processes, or changing or omitting data or results such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record" (OSTP 2000, 76260-4). Falsification includes inappropriately manipulating existing results to fit a preferred hypothesis or altering data to make them appear more convincing than they actually are. Falsification can take many forms. For example, it can occur in figures, graphs, and digital images. For example, the animal researcher, Li Chen, was found guilty of falsifying and fabricating data reported in publications and in National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant applications. Chen also falsified figures by reusing and relabeling an image and claiming that it represented different experiments, and falsely reported that the identical image represented several different experimental treatments (Grant 2014). PLAGIARISM "Plagiarism is the appropriation of another person's ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit" (OSTP 2000, 76260-4). Plagiarism can appear in a journal article, a conference paper, or many other venues; it occurs when someone else's words or ideas are used, such as in a results or discussion section, without giving proper credit or attribution to the original author. For example, Carleen Basler resigned from the Anthropology and Sociology Department at Amherst College after admitting that her written work contained plagiarized content (Reyes 2012). Basler's papers contained numerous instances of unattributed verbatim quotations. She did not properly reference the work of other scholars. WHY RESEARCH MISCONDUCT OCCURS INDIVIDUAL FACTORS There are a variety of reasons why an individual might engage in research misconduct. Stress and personality traits, such as arrogance or indifference, can be key contributing factors. Self-deception or rationalization of certain behaviors may also influence one's willingness to engage in research misconduct. For example, if researchers convince themselves that a preferred hypothesis is correct and do not collect enough data to support that hypothesis, they may find themselves heading down a path towards research misconduct. Individuals at any career stage may be tempted to engage in research misconduct. For example, a student might feel pressure to get good grades or complete a project on time. A faculty member may feel pressure to publish data and obtain grant funding in order to secure a promotion or tenure. A postdoctoral researcher might engage in research misconduct to obtain results quickly in order to move on to the next career stage. Alternatively, a researcher might pressure a collaborator into committing an act of misconduct. ORGANIZATIONAL FACTORS An organization's stance on the importance of research integrity sets the tone for its students and employees to follow. Conversely, the lack of an ethical climate within an organization can have corrosive effects. If individuals are not held accountable for bad behavior and rules are not enforced, research misconduct can become pervasive within an organization. Moreover, research misconduct is often connected to poor or inadequate mentoring (Anderson et al. 2007). For example, when a senior researcher does not spend enough time reviewing trainees' data or teaching them appropriate research methods, the occurrence of problematic behaviors is more likely. RELATED FACTORS The availability of certain kinds of technology, such as the Internet for acquiring information for writing assignments or software tools to alter digital images, can make research misconduct more common. Unfortunately, the ease with which researchers and others can copy text or manipulate data can create an opportunity to engage in research misconduct. OTHER PROBLEMATIC RESEARCH BEHAVIORS QUESTIONABLE RESEARCH PRACTICES Behaviors that closely border on research misconduct but do not fall under its strict definition are often referred to as questionable research practices (QRPs) (NRC 1992). Examples of QRPs include failing to disclose negative outcomes or stopping research prematurely if a preferred outcome seems to have been achieved. Other examples of QRPs include inappropriate research design and using a flawed statistical analysis to support a hypothesis. Other behaviors that affect research integrity include ignoring or circumventing organizational policies and not properly disclosing conflicts of interest (Martinson et al. 2005). AUTHORSHIP DISPUTES Disagreements about authorship should be referred to the appropriate entities within the organization, such as a research director, or external entities, such as a journal editor. Although authorship disputes can certainly become ethically problematic. THE EFFECTS OF RESEARCH MISCONDUCT ON SOCIETY Society contributes to the advancement of knowledge through public funding of research. When any researcher or research community engages in misconduct or allows it to occur, the public trust is betrayed and its funds squandered. Moreover, valuable resources and time are wasted when other researchers attempt to build on or replicate erroneous research. Society as a whole suffers when researchers conduct fake, deceptive, or otherwise unethical research. What makes this problem more serious is that identifying and determining the impact of a research misconduct case can sometimes take years. For example, if data relating to the side effects of a medication have been manipulated, the public may think or be told the medication is safer than it actually is. Steen (2011) examined about 200 papers in the area of medical research and clinical trials that were retracted due to questionable data; he comments that these retracted papers may have affected the medical care of thousands of patients. Along similar lines, research published by anesthesiologist Scott Reuben altered the way physicians provide pain relief to patients undergoing orthopedic surgery; however, much of his work contained partially or completely fabricated data. An investigation revealed that at least 21 of Reuben's papers were pure fiction (Borrell 2009). STRATEGIES FOR PREVENTING OR MITIGATING RESEARCH MISCONDUCT Policies and guidelines are useful tools. However, factors such as cultural influences and education level can affect perceptions of whether a particular behavior is acceptable or not. Open and ongoing discussions about proper research practices are crucial. For example, it should not be assumed that each member of a multi-national research team has the same understanding about what constitutes plagiarism. Setting the right tone and good mentoring go a long way towards enhancing research integrity. Encouraging mentoring throughout an organization is an effective strategy for preventing misconduct. Other prevention strategies, such as periodically verifying data collection methods, and discussing roles and responsibilities before and during a research project, are also essential. Seeking clarification and advice from trusted colleagues or an ombudsperson when something seems awry can also help avert misconduct. As Steinberg (2002) notes, "The smart move is to incorporate preventive strategies into your everyday business practices so staff and colleagues know what is expected of them and of you." SUMMARY Research misconduct can occur in any field of research. Strategies for preventing, mitigating, and detecting research misconduct are evolving. Organizations must have policies and procedures for handling allegations of research misconduct. Researchers have an obligation to avoid engaging in research misconduct or other behaviors that the research community would condemn and that erode public trust. Quiz: Which type of inappropriate practice most likely occurred if a researcher takes credit for someone else’s idea and does not acknowledge the original source? • Falsification • Plagiarism • Conflict of interest • Fabrication Which of the following is most likely to be considered plagiarism? • Tampering with research equipment. • Intentionally reporting the results of inaccurate statistical tests. • Using materials from a source without proper citation. • Adding extra data points without proper justification Further Insights on Researching Human Subjects (in case you are planning to use classroom research or interviews/ questionnaires/ Observations) ETHICAL PRINCIPLES OF THE BELMONT REPORT RESPECT FOR PERSONS Respect for persons incorporates at least two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection. The principle of respect for persons thus divides into two separate moral requirements: the requirement to acknowledge the autonomy and the requirement to protect those with diminished autonomy. AUTONOMY Autonomy means that people must be empowered to make decisions concerning their own actions and well-being. According to the principle of respect for persons, researchers must acknowledge the "considered opinions and choices" of research subjects. In other words, individuals must be given the choice whether to participate in research, and they must be provided sufficient information and possess the mental competence to make that choice. Respect for persons also recognizes that some individuals may not be capable of making decisions or choices that are in their best interest. Individuals with "diminished decision-making capacity" may lack the ability to comprehend study procedures or how participating in a study might adversely affect them. Special care should be taken to protect those with diminished capacity to the point of excluding individuals who are not able to give meaningful consent to participate in research. Children are a class of research subjects with limited autonomy. Typically, a parent or legal guardian must give permission for a child to participate in a study. Researchers also should ask child subjects for their assent by explaining the study in terms they can understand. VOLUNTARINES Voluntariness is an essential component of respect for persons. Research subjects must be free to choose to participate in research. They also must be free to end their participation for any reason, without consequences. Voluntariness means more than offering people the choice to participate in or withdraw from research. Researchers should be aware of situations in which prospective subjects may feel pressured to participate in a study. In situations where a relationship between the researcher and subjects already exists, such as when a volunteer at a homeless shelter decides to conduct research with that population, the lines between voluntariness and undue influence may be blurred. People might be reluctant to decline participation if they have come to know the researcher in another role. Other examples of situations in which researchers may exert undue influence because they are in positions of authority include: employers conducting research with their employees and professors conducting research with their students. INFORMED CONSENT A prospective research subject's autonomy is honored through the process of informed consent. The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP 2014) offers these guidelines: The informed consent process involves three key features: (1) disclosing to potential research subjects information needed to make an informed decision; (2) facilitating the understanding of what has been disclosed; and (3) promoting the voluntariness of the decision about whether or not to participate in the research. Researchers must provide certain essential points of information, such as the purpose of the research, a description of what the subject will be asked to do, any foreseeable risks of harm, and that the study is voluntary and subjects are free to withdraw at any time. Informed consent also must be comprehensible to prospective subjects. Comprehension is the ability to understand what one is being asked to do, as well as the implications of any risks of harm associated with participating in the research. Comprehension may refer to an individual's mental capacity, but it also relates to the comprehensibility of the informed consent document, or, in the case of oral consent, the script. Researchers should create consent processes that are at an appropriate language level for the subject population. Study information can be presented in a conversational style that is easily understood by a wide range of individuals. In general, an eighth grade reading level or lower is advised. When conducting research in a language other than the researcher's native language, the researcher needs to ensure that translations are accurate and in the appropriate vernacular, and address idiomatic expressions that may not make sense in another language. BENEFICENCE Persons are treated in an ethical manner not only by respecting their decisions and protecting them from harm, but also by making efforts to secure their well-being. Such treatment falls under the principle of beneficence. The term 'beneficence' is often understood to cover acts of kindness or charity that go beyond strict obligation. In this document, beneficence is understood in a stronger sense, as an obligation. Two general rules have been formulated as complementary expression of beneficent actions in this sense: (1) do not harm and (2) maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms (The National Commission 1979). Most research in the social and behavioral sciences, education, and the humanities, does not provide direct benefit to subjects, and risks of harm tend to be minimal. The most common risks of harm are psychological distress surrounding sensitive research and inadvertent disclosure of private identifiable information. Studies of sexuality, mental health, interpersonal violence, and illegal activities may create feelings of distress as well as risk of embarrassment and reputational harm if private information that would not ordinarily be shared with a stranger or outsider becomes public. Researchers may choose to use pseudonyms in an effort to protect the privacy of subjects, but other bits of information, taken alone or in combination, may be enough to allow for re-identification of subjects. A great deal of research in the social and behavioral sciences, however, involves minimal risk procedures, such as gathering and reporting on aggregate data using surveys and interviews. Some research involves deception, which is permissible, if researchers provide justification for the deception and prepare debriefing procedures for the subjects at the end of the study that describe the deception and explain the scientific rationale for its use. Frequently, it is not the nature of the data collected but what the researcher does with the data that carries the most risk of harm for subjects. Data security and the very notion of privacy have changed dramatically with the explosion of social media, cloud storage, data mining of web-based information, and re-identification techniques. Refraining from collecting subject names is a simple way of reducing risk of harm due to inadvertent disclosure of private identifiable information. As we have seen from the Harvard T3 study, however, that is rarely sufficient as data re-identification has emerged as a growing computer science specialization. Latanya Sweeney (2000), director of the Data Privacy Lab at Harvard University, has demonstrated that 87 percent of Americans can be uniquely identified by only three bits of demographic information: five-digit zip code, gender, and date of birth. Informed Consent There is general consensus on the importance of informed consent in research. Most people have the expectation that they will be treated with respect and as autonomous individuals. They also expect that they have the right to make decisions about what will and will not be done to them and about what personal information they will share with others. However, researchers also are aware that there are circumstances in which obtaining and documenting consent in social and behavioral research may be a complex, and often challenging, process. For instance, potential subjects may be fluent in a language but not literate. Researchers may need to deceive research subjects in order obtain scientifically valid data. Asking subjects to sign consent forms linking them to a study about illegal activities could put them at risk of harm. OVERVIEW OF INFORMED CONSENT Most regulations require researchers to obtain legally effective informed consent from the subject or the subject's legally authorized representative. There are two parts to informed consent. The first is the process of providing information to prospective subjects. The second is documentation that the process took place and is a record of the subjects' agreement to take part in the study. THE PROCESS Informed consent is a process that begins with the recruitment and screening of a subject and continues throughout the subject's involvement in the research. It includes: Providing specific information about the study to subjects in a way that is understandable to them. Answering questions to ensure that subjects understand the research and their role in it. Giving subjects sufficient time to consider their decisions. Obtaining the voluntary agreement of subjects to take part in the study. The agreement is only to enter the study, as subjects may withdraw at any time, decline to answer specific questions, or complete specific tasks at any time during the research. DOCUMENTATION Documentation of consent provides a record that the consent process took place. It generally consists of a consent form signed by the subject or the subject's LAR. In practice, this document often is used as a tool for engaging in the consent process. BASIC ELEMENTS A statement that the study involves research, an explanation of the purposes of the research and the expected duration of the subject's participation, a description of the procedures to be followed, and identification of any procedures which are experimental. A description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject. A description of any benefits to the subject or to others, which may reasonably be expected from the research. If there are no direct benefits, the researchers may tell subjects what they hope to learn, how that knowledge will contribute to the field of study or how the knowledge might benefit others if such a case can be made. A disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any, that might be advantageous to the subject. The description must include a full disclosure of any state-mandated reporting requirements, such as suspicion of child abuse and/or neglect or harm to others, when warranted by the topic under investigation. State requirements vary, so IRBs and researchers must be aware of state-specific information. For research involving more than minimal risk, an explanation as to whether any medical treatments are available if injury occurs and, if so, what they consist of, what compensation will be provided, and where further information may be obtained. An explanation of whom to contact for answers to pertinent questions about the research and research subjects' rights, and whom to contact in the event of a research-related injury to the subject. In some field research, there may not be any way for subjects to call or email anyone about their questions and concerns. Alternative means of communication must be established, such as a local contact on the research team. A statement that participation is voluntary, refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled, and the subject may discontinue participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled. Most researchers in the social and behavioral sciences are not in a position to impose penalties. However, specific study-related assurances that there will be no negative consequences associated with choosing not to take part might be appropriate. For example, parents may need to be assured that if they choose not to participate in a school-based, school-approved study their children's grades or placement will not be affected. ADDITIONAL ELEMENTS Depending upon the nature of the research and the risks involved, there may be additional required elements, including: A statement that the particular treatment or procedure may involve risks to the subject (or the embryo or fetus, if the subject is or may become pregnant), which are currently unforeseeable. Anticipated circumstances under which the subject's participation may be terminated by the investigator without regard to the subject's consent. Any additional costs to the subject that may result from participation in the research. The consequences of a subject's decision to withdraw from the research and procedures for orderly termination of participation by the subject. Subjects need to know, for example, how their compensation will be affected if they choose not to complete an interview. Discussion of what happens to data already collected if they withdraw midway through the study also may be addressed in this section. A statement that significant new findings developed during the course of the research which may relate to the subject's willingness to continue participation will be provided to the subject. This requirement applies primarily to biomedical research involving new treatments and procedures, but also may apply to research on experimental behavioral interventions. The approximate number of subjects involved in the study. INCENTIVES Incentives are payments or gifts offered to subjects as reimbursement for their participation. These must be described during the consent process as well as the conditions under which subjects will receive partial or no payment. RECRUITMENT Recruitment is part of the consent process because it begins the process of providing information about the study. All recruitment strategies such as fliers, email messages, newspaper advertisements, phone scripts, and so on must be reviewed and approved by an IRB before they are used. EXCULPATORY LANGUAGE Subjects may not be asked to waive or even appear to waive any of their legal rights. They may not be asked to release a researcher, sponsor, or institution from liability for negligence. Institutions may provide information about how liabilities will be covered. ENSURING COMPREHENSION OF CONSENT INFORMATION Researchers are required to provide information in a manner understandable to the subjects. This requires preparing material in the subjects' language at the appropriate reading level. When a study is complex and/or the reading or educational level of the prospective study population is low, the role of dialog and explanation becomes an even more crucial part of the consent process. ENSURING FREE CHOICE The principle of respect for persons requires that participation in research be truly voluntary, free from coercion or undue influence. Even when a study is innocuous, subjects must be informed that they do not have to take part, and they may choose to stop participating at any time. SETTING AND TIME Researchers should consider ways in which the setting of the consent process might include elements of undue influence. Potential subjects might not feel entirely free to choose whether to take part in a research study if they are: Adolescents whose parents are in the room Adolescents in a group of other adolescents being recruited for the same study Parents who receive a letter from the school principal asking them for permission to enroll their children in a study Athletes recruited by their coach Employees asked to take part by their employer Subjects must be given adequate time to consider whether they wish to take part in a study. This is particularly true if the study procedures involve more than minimal risk or will require subjects to disclose sensitive information. Compensation or incentives to participate may not be so high that they override other considerations for potential subjects. Determining whether incentives are unduly influential depends on the research context and the financial and emotional resources of the subjects. SAFEGUARDS FOR VULNERABLE SUBJECTS DURING CONSENT Most regulations ensure that appropriate safeguards are in place to protect the rights and welfare of subjects likely to be vulnerable to coercion or undue influence. Potentially vulnerable subjects include children, prisoners, pregnant women, mentally disabled persons, or economically or educationally disadvantaged persons. WAIVERS OF DOCUMENTATION Documentation of the consent process is not always required. Note, however, that waivers of documentation are not waivers of the consent process itself. For waivers of consent, see the criteria noted above. Documentation may be waived under two circumstances: The principal risks are those associated with a breach of confidentiality concerning the subject's participation in the research, and the consent document is the only record linking the subject with the research. For example: Research about women who have left abusive partners. Research on the black market capitalist economy in Cuba in which illicit vendors will be interviewed in a safe space. When the requirement for documentation is waived, the IRB may require the researcher to offer the subjects information about the study in writing. Study participation presents minimal risk of harm to the subject and the research involves no procedures requiring consent outside the context of participation in a research study, for example, a telephone survey. SUMMARY Informed consent includes both the process of sharing information and documenting that the process took place. To ensure that potential subjects can truly make informed decisions about whether to take part in research, issues of comprehension, language, and culture need to be considered in addition to the elements of information provided in the regulations. The regulations provide criteria for waiving any or all of the elements of information and the documentation of consent. PRIVACY AND CONFIDENTIALITY "Privacy can be defined in terms of having control over the extent, timing, and circumstances of sharing oneself (physically, behaviorally, or intellectually) with others. Confidentiality pertains to the treatment of information that an individual has disclosed in a relationship of trust and with the expectation that it will not be divulged to others, in ways that are inconsistent with the understanding of the original disclosure without permission." Although privacy and confidentiality are closely related, they are not identical. Privacy is related to methods of gathering information from research subjects; confidentiality refers to the obligations of researchers and institutions to appropriately protect the information disclosed to them. Confidentiality procedures, as described during the informed consent process, allow subjects to decide what measure of control over their personal information they are willing to relinquish to researchers. It is not always the case that identifiable information provided by research participants must be protected from disclosure. Some participants want to be identified and quoted. Some agree to have their photographs, audio, or video recordings published or otherwise made available to the public. CONFIDENTIALITY Researchers provide confidentiality to their subjects by appropriately protecting information the subjects disclose. The potential risk of harm to subjects if identifiable data were inadvertently disclosed is the key factor for determining what kinds of protection are needed. The ideal way to protect research data is not to collect information that could identify subjects, that is, neither direct identifiers such as names or email addresses, nor indirect identifiers such as information that could be used to deduce subjects' identities. If researchers plan to retain individually identifiable data that if inadvertently disclosed could place participants at risk of harm, researchers need to design procedures to protect the data during collection, storage, analysis, and reporting. These procedures could include creating keys linking subjects' names to unique numbers associated with the data, storing encrypted data on secure servers, removing identifiers when data collection is completed, reporting data in aggregate, and creating misleading identifiers in articles or presentations. Consent forms should clearly explain who will have access to identifiable data, both in the present and in the future, and describe any future uses of the data. For example, if researchers want to show video clips of research subjects during conference presentations or use them in a classroom, the subjects must be asked for permission to use their images in those ways. Although privacy and confidentiality deal with different aspects of a study design, how these two issues are handled translate into issues of trust and security for a research participant. Practice Questions: Question 1 Which of the following constitutes both a breach of confidentiality (the research data have been disclosed, counter to the agreement between researcher and subjects) and a violation of subjects’ privacy (the right of the individuals to be protected against intrusion into their personal lives or affairs)? In order to eliminate the effect of observation on behavior, a researcher attends a support group and records interactions without informing the attendees. • A researcher asks cocaine users to provide names and contact information of other cocaine users who might qualify for a study. • A researcher, who is a guest, audio-records conversations at a series of private dinner parties to assess gender roles, without informing participants. • A faculty member makes identifiable data about sexual behavior available to graduate students, although the subjects were assured that the data would be de-identified. Data are made anonymous by • Destroying all identifiers connected to the data. • Keeping the key linking names to responses in a secure location. • Reporting data in aggregate form in publications resulting from the research. • Requiring all members of the research team to sign confidentiality agreements When a focus group deals with a potentially sensitive topic, which of the following statements about providing confidentiality to focus group participants is correct? • The researcher cannot control what participants repeat about others outside the group. • Using pseudonyms in reports removes the concern about any confidences shared in the group. • If group members know each other confidentiality is not an issue. • If group participants sign confidentiality agreements, the researcher can guarantee confidentiality. A researcher leaves a research file in her car while she attends a concert and her car is stolen. The file contains charts of aggregated numerical data from a research study with human subjects, but no other documents. The consent form said that no identifying information would be retained , and the researcher adhered to that component. Which of the following statements best characterizes what occurred? • Confidentiality of the data has been breached. • There was neither a violation of privacy nor a breach of confidentiality. • The subjects’ privacy has been violated. • There was both a violation of privacy and a breach of confidentiality. In a longitudinal study that will follow children from kindergarten through high school and will collect information about illegal activities, which of the following confidentiality procedures would protect against compelled disclosure of individually identifiable information? • Using pseudonyms in research reports. • Using data encryption for stored files. • Securing a Certificate of Confidentiality. • Waiving documentation of consent. INDIVIDUALLY IDENTIFYING INFORMATION Protecting subjects' privacy as well as the confidentiality of identifiable study data requires considering the ways people identify themselves when using the Internet. For example, individuals' Internet identities may be very different from their "real" (or offline) identities. Although researchers may not use a subject's real name, that subject's online username may serve as that subject's Internet identity. In this scenario, a subject's online name is considered a direct identifier. Similarly, if a researcher reports on the features and attributes of an individual's MMORPG character (for example, the character's race, job classification, equipment, weaponry, and ranking), this may indirectly identify the individual. Should researchers afford individuals' online identities the same protections as their offline identities? There are other re-identification methods unique to the Internet. For example, direct quotes taken from a blog post or forum response can be retrieved easily using a simple Google search and thus may reveal the identity of the author. A series of unique data points also may allow subject reidentification, specifically if these data points appear in more than one dataset. In addition, information that may not seem sensitive or identifiable at the time of collection may become sensitive or identifiable, inadvertently, as technological advances help researchers link, combine, and analyze data (Thompson 2012). One unique data point that could, conceivably, be used to re-identify someone is to use an Internet Protocol (IP) address. An IP address is a unique identification number assigned to every computer connected to the Internet, and is used by websites to send and retrieve information. It is said the Internet "runs on IP addresses," which is perhaps the reason why it is quite simple to trace an IP address. In fact, there are several sites that provide users with instructions on how to trace an IP address in a matter of steps. Though it is not always possible to track down a specific individual using an IP address alone, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule considers IP addresses direct identifiers, as does the European Union (OHRP 2010; HHS 2012b). Some online research service providers, such as the survey toolbuilder Qualtrics, offer researchers the option to be given their data without an IP address as an added measure to protect the confidentiality and privacy of respondents. APPLYING ETHICAL PRINCIPLES TO INTERNET-BASED RESEARCH Respecting the autonomy of subjects and minimizing potential risks of harm to subjects are ethical principles most relevant to internet-based research. 1. HOW CAN RESEARCHERS RESPECT THE AUTONOMY OF SUBJECTS IN INTERNET-BASED RESEARCH? Respecting the autonomy of subjects requires researchers to give prospective subjects adequate information to make an informed decision before agreeing to participate in a study. This is done through the informed consent process, which includes: Providing subjects with the information they need in order to decide whether to take part in a study Documenting that the information was provided and that the subject volunteered to take part in the study The kind of information provided on an online consent form, is identical to the kind of information provided on an offline consent form. This includes most, if not all, of the required elements of informed consent. For example, one would expect the informed consent process to provide the expected duration of the study, the procedures to follow, a description of the extent, if any, to which the confidentiality of subjects' information will be maintained, and the researcher's contact information. A description of the voluntary nature of participation also is important. This means that subjects are allowed to withdraw from the study or skip questions or study-related tasks without negative consequences. Documenting consent online is quite different from documenting consent in person. Documenting consent in person often consists of a signed form that researchers and subjects keep in their possession. The challenge in designing a consent process for online studies is that they usually do not provide an opportunity for the researchers and subjects to directly interact. Fortunately for researchers, the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) allows them to obtain an electronic signature as a way to document consent (HHS 2012a). An electronic signature can be an embedded image of a subject's signature, a handwritten signature produced by a tablet computer, or encrypted digital signature (Thompson 2012). Nonetheless, the Common Rule allows IRBs to waive the requirement to document consent from subjects, as long as the study presents no more than minimal risk of harm to subjects and the research does not involve procedures requiring consent outside the context of participation in the study (Protection of Human Subjects 2009). However, waiving the requirement to document consent does not waive the requirement for providing a consent process. One method of providing a consent process is to design an online consent form that includes a "live button" that subjects can click to demonstrate their consent. This version of an online consent form should include a statement to the effect of, "Clicking below indicates that I have read the description of the study and I agree to participate in the study." This way, subjects are actively demonstrating their consent to participate. Note that this process does not produce a signed consent form for subjects or researchers to store as part of their research records. Other methods for securing consent for online studies include obtaining an electronic signature, as noted above, or sending a paper consent form to the subject via mail. Although the latter method produces a signed consent form, it also requires that the researcher collect personally identifiable information about their subjects that may not be necessary (Thompson 2012). Securing consent online also raises issues regarding children. In the U.S., each state determines the age of legal majority, and the age of legal majority differs from country to country. Unfortunately, researchers recruiting via the Internet cannot know where respondents reside or whether respondents are 15 or 51. Researchers may use informal age verification measures, such as asking subjects to provide their age or year of birth, or by stating that subjects must be considered an adult to participate. However, these techniques do not guarantee honest responses or compliance. Researchers could make use of several age verification methods that may prevent minors from participating in research, such as age verification services (AVS). Nonetheless, Internet research experts argue that these products, though robust, are not infallible (Thompson 2012). Thus, in the absence of a foolproof method for determining the ages of Internet users, researchers and IRBs should carefully consider approval of some of the types of online studies endeavored. Another issue related to respecting the autonomy of subjects and internet-based research includes incomplete disclosure, deception, and the complete absence of an informed consent process. The Internet offers researchers compelling opportunities to study behavior unmediated by the presence of an observer. The Internet also provides unique opportunities for observational research in private settings. For example, a researcher can register as a member of a closed group with relative ease to observe interactions among the members, while concealing his or her identity as a researcher, or use public blog posts about a group of individuals' private lives for research purposes without the individuals' consent. An IRB also may approve studies in which the informed consent process is completely waived, if it determines that the waiver is justified. For example, if a researcher wanted to study behavior and interactions among users of online virtual worlds, such as Second Life, the IRB could waive the requirement to obtain consent because consenting might alter the subject's behavior, thus making the consent process impracticable. In these types of studies, researchers "lurk" to collect data. In some instances, researchers may even adopt a false identity or create a fictitious website in order to observe private behavior. Nonetheless, the relative ease of collecting data without consenting subjects calls for more discussion about applying ethical guidelines to research conducted in Internet environments. As discussed earlier, other issues pertaining to respecting the autonomy of subjects include whether researchers bear the responsibility to interpret their subjects' expectations of privacy and how to recognize those expectations. 2. HOW CAN RESEARCHERS MINIMIZE POTENTIAL RISKS OF HARM TO RESEARCH SUBJECTS IN INTERNET-BASED RESEARCH? The greatest risk of harm to subjects taking part in social and behavioral sciences research is the inadvertent disclosure of private identifiable information that could damage their reputations, employability, insurability, or subject them to criminal or civil liability. However, several factors need to be considered when assessing potential risks, and because it may be difficult to determine where online subjects reside, assessing potential risks of harm becomes problematic. But in most internet-based research, the primary risk of harm is loss of confidentiality. Re-identification of Data Re-identification methods are unique to internet-based research. Two examples of re-identifying presumably de-identified datasets are the Harvard University study "Taste, Ties, and Time (T3)" in 2008 and the America Online (AOL) search data leak in 2006. The T3 study was a longitudinal study conducted by a group of researchers at Harvard University and the University of California, Los Angeles. The team was investigating the nature and dynamics of social networks using Facebook data from an entire cohort of undergraduate students at a university in the northeastern U.S. The researchers began collecting data in 2006 and continued data collection through 2009, at one-year intervals for each year of the cohort's college career. The result was a dataset that included "machine-readable files of virtually all the information" from 1,700 students' Facebook profiles (Lewis et al. 2008). Because the project was funded in part by an award from the National Science Foundation (NSF), the researchers were obligated by the terms of the award to share some of their data. In an attempt to protect the privacy of their subjects, the researchers did not identify the institution, removed student names and identification numbers from the dataset, and delayed releasing the cultural interests of subjects, such as movies, books, TV shows, and music. Additionally, the researchers required other researchers to agree to a "terms and conditions for use" that prohibited any attempts to re-identify subjects, disclose any identities that might be inadvertently reidentified, or otherwise compromise the privacy of the subjects. On September 25, 2008, the researchers made the first wave of de-identified data available to the public (Zimmer 2010, 31325). Within days, a researcher from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee was able to determine that the data came from Harvard University, and he did so without accessing the full dataset (Zimmer 2010, 313-25; Parry 2011). Although he did not identify individual students, it was clear that the dataset included enough unique indirect identifiers to re-identify the students (Zimmer 2010, 313-25; Parry 2011). In the AOL search data leak of 2006, the Internet service provider, AOL, released a dataset that included the search records of 500,000 of its users. AOL, in good faith, had intended to make the data available to benefit academic researchers. AOL had stripped the names from the data released and provided only what were supposed to be unidentifiable user numbers. However, within days, journalists from the New York Times were able to discover the identity of user number 4417749 by simply investigating the unique search queries, which were notable for various reasons. The company eventually removed the data (Hafner 2006; Jones 2006; Zeller 2006). DATA STORAGE How the data are stored also raises confidentiality issues. As technologies such as cloud computing, for example Dropbox, develop to facilitate research, researchers can expect more challenges. Cloud computing is the storage and delivery of resources, software, and information over an online network, rather than a physical product (Mell and Grance 2011). Resources, software, and information are uploaded to and stored on "cloud servers" in the U.S. and abroad. Users can then access and share these files remotely, and with relative ease. Encrypting data before uploading it to a cloud server is a recommended security measure. Data Mining New technologies are paving the way for careers and professions in data mining. Data mining is a field of computer science that involves methods such artificial intelligence, statistics, database systems management, and data processing to detect patterns from large data sets (Chakrabarti et al. 2006). Academic institutions now offer training to individuals who want to use statistical methods to extract useful information from large, multiple datasets that can be used for research purposes, including marketing (Boston University 2012; Northwestern University 2012). It is important to consider the source of the data before mining it. Unauthorized Access Researchers may use data scraping techniques to collect information from Facebook or public blog posts without consent. This is particularly concerning if email communications, although a popular method to recruit subjects, are not secure and may provide a record of subjects' identities. Similarly, hacking and unauthorized computer access has become an everyday possibility that researchers need to anticipate when conducting research in the digital age. Encrypting data while it is stored on a researcher's server is a recommended security measure. It is for these reasons that researchers should collaborate with information technology (IT) professionals to develop a data security plan. However, even the most careful security procedures used by a researcher can be voided if the subjects' computers are not secure. Describing Risks to Subjects As mentioned in the previous section, the informed consent process should describe the extent, if any, to which the confidentiality of subjects' personally identifiable information will be maintained. It is clear that ensuring the confidentiality of personally identifiable information is challenging in internet-based research. Some internet-based research experts have identified several "best practices" for describing confidentiality protections to subjects. Some of these best practices include an explanation of how data are transmitted from the subject to the researcher, how the researcher will maintain and secure the data, and a discussion to emphasize that there is no way to guarantee absolute confidentiality (Thompson 2012 ; Office for the Protection 2012). SUMMARY Though the Internet has much to offer researchers, researchers using it have several issues to consider before designing an online research study. Some of these issues include user expectations about the privacy of their information, informed consent processes, potential for reidentification of collected data, and that there are no absolute guarantees to ensure the confidentiality of personally identifiable information. Navigating these issues becomes much more intricate and complex when adding the fluid nature of the online world and the rapid development of new Internet technologies into the equation. It is for these reasons that experts in the field of Internet research ethics have described internet-based research as a "moving target." MORE RESOURCES Some helpful resources include: MichaelZimmer.org - the blog of Dr. Michael Zimmer, assistant professor in the School of Information Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and co-director of the Center for Information Policy Research. MichaelZimmer.org offers relevant commentary on information ethics, privacy, new media, and values in design. The University of California-Berkeley guidance on internet-based research - an eight-page document created by the University of California-Berkeley Institutional Review Board.

![Informed Consent Form [INSERT YOUR DEGREE]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007051752_2-17c4425bfcffd12fe3694db9b0a19088-300x300.png)