2022-L1V6 PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT AND ETHICAL AND PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS (1)

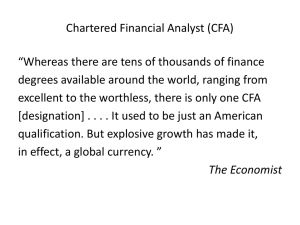

advertisement