DATE DOWNLOADED: Mon Dec 13 21:43:25 2021

SOURCE: Content Downloaded from HeinOnline

Citations:

Bluebook 21st ed.

John Kaplan, The Limits of the Exclusionary Rule, 26 Stan. L. REV. 1027 (1974).

ALWD 7th ed.

John Kaplan, The Limits of the Exclusionary Rule, 26 Stan. L. Rev. 1027 (1974).

APA 7th ed.

Kaplan, J. (1974). The Limits of the Exclusionary Rule. Stanford Law Review, 26(5),

1027-1056.

Chicago 17th ed.

John Kaplan, "The Limits of the Exclusionary Rule," Stanford Law Review 26, no. 5

(May 1974): 1027-1056

McGill Guide 9th ed.

John Kaplan, "The Limits of the Exclusionary Rule" (1974) 26:5 Stan L Rev 1027.

AGLC 4th ed.

John Kaplan, 'The Limits of the Exclusionary Rule' (1974) 26 Stanford Law Review

1027.

MLA 8th ed.

Kaplan, John. "The Limits of the Exclusionary Rule." Stanford Law Review, vol. 26,

no. 5, May 1974, p. 1027-1056. HeinOnline.

OSCOLA 4th ed.

John Kaplan, 'The Limits of the Exclusionary Rule' (1974) 26 Stan L Rev 1027

-- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and

Conditions of the license agreement available at

https://heinonline.org/HOL/License

-- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text.

-- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your license, please use:

Copyright Information

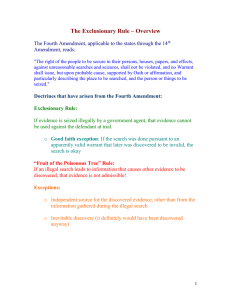

The Limits of the Exclusionary Rule

John Kaplan*

It is to Herbert Packer that we owe in their clearest forms two of our

major modern insights into the criminal system. First, it is he who most

clearly identified the major tensions in our adversary system as two fundamentally different ways of looking at the criminal process-the crime control and the due process models The crime control model focuses on the

role of the legal system in repressing criminal conduct. Its primary value

is efficiency, both in the apprehension and punishment of the guilty and

in the screening out of the innocent at as early a stage as possible. It conceives of the processes of justice in terms of managerial efficiency. The due

process model is more complex. It is designed, beyond the mere separation

of the guilty from the innocent, to assure basic rights of fairness to the

accused and to protect his personal dignity. In Professor Packer's astute

phrase, "If the Crime Control Model resembles an assembly line, the Due

Process Model looks very much like an obstacle course."'

Second, he engendered in a whole generation of criminal law scholars

an extreme skepticism about the use of the criminal sanction in the area of

nonvictim crime.3 It is his outlook, developed in The Limits of the Criminal

Sanction4 and a host of earlier writings,5 which has become the conventional wisdom among those thinking most about the criminal law.

Though across-the-board denunciations of nonvictim offenses are sometimes heard today, Packer himself was much more careful and sophisticated about the problem. His view was not that all nonvictim crimes are

a misuse of the criminal sanction. That category, after all, includes minimum wage laws and rules concerning safety appliances on automobiles.6

Rather, he pointed out that gambling, drug offenses, prostitution, and a

relatively small number of other nonvictim crimes put an undue strain upon

*A.B. 1951, L.L.B. 1954, Harvard University. Professor of Law, Stanford Law School. I would

like to express my appreciation to Andrew Lipps, Stanford Law School, Class of 1974. His research

and criticism were above and beyond the call of duty.

I. H. PACKER, THE Lrtrrs OF Tim CRnnNaL SANCTioN L49-246 (1968); see Goldstein, Reflections

on Two Models: InquisitorialThemes in American CriminalProcedure, 26 STAzq. L. REV. 1009 (x974).

2. H. PACKER, supra note r, at 163.

3. Id. at 249-366.

4. H. PACKER, supranote x.

5. E.g., Packer, The Crime Tariff, 33 Am. SCHoLtAR 55r (1964); Packer, Offenses Against the

State, 339 ANNALs 77-89 (1962); Packer, The Model Penal Code and Beyond, 63 COL-M. L. Ray.

594 (1963); Packer, The Courts, The Police, and the Rest of Us, 57 J. CRni. L.C. & P.S. 238 (1966);

Packer, Policing the Police, NEw REPurLmC, Sept. 4, x965, at 17-21; Packer, Two Models of the

Criminal Process, 113 U. PA. L. Rxv. 1 (1964); Packer, Copping Out (Book Review), NEw YoRKc

REV Ew OF Booxs, Oct. 12, 1967, at 17.

6. See Kaplan, The Role of the Law in Drug Control, 1971 DtrE L.J. o65.

1027

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26: Page 1027

our criminal enforcement mechanisms and cause societally damaging results which outweigh any gains produced by the use of criminal law.

Though the problems created by applying the criminal sanction vary with

the offense involved, one pervasive similarity emerges. Whether or not society regards him as a victim, a willing participant in a nonvictim crime

generally is unlikely to complain to the police. Regardless of how greatly

a heroin addict is exploited by his connection, the very drives that lead him

to be so exploited also prevent his voluntary cooperation with law enforcement. This lack of a complainant forces the police to use other tactics

which not only are less effective than a victim's complaint, but which also

tend to intrude upon constitutional values.

In this brief essay in Professor Packer's memory, it is particularly appropriate to discuss an area which lies near the intersection of these two

significant contributions. The exclusionary rule is probably the point of the

clearest conflict between the demands of due process and crime control

values identified.by Professor Packer. Due process values demand general

laws to protect the citizen from at least some governmental intrusions into

his privacy through searches and seizures.' The exclusionary rule, its proponents claim, is the only way to enforce such laws.' On the other hand,

any rule which makes rationally probative and often vital evidence against

a defendant inadmissible in his criminal prosecution flies in the face of

crime control values.' The relation between the exclusionary rule and nonvictim crime is also clear. As any examination of appellate reports reveals,

the great majority of cases in which the exclusionary rule is considered are

cases involving nonvictim crime. The number is far out of proportion even

to the approximately 50 percent of arrests which involve such crimes. 1 The

due process values protected by the exclusionary rule are related to nonvictim crime in yet another way. It is probable that in any modern nation in

which there is governmental respect for individual privacy many people

will engage in nonvictim crimes.' Indeed, one of the earmarks of a police

7. H. PACKER, supra note i, at 296-366.

8. "[T]he Due Process Model, although it may in the first instance be addressed to the maintenance of reliable fact-finding techniques, comes eventually to incorporate prophylactic and deterrent

rules that result in the release of the factually guilty even in cases in which blotting out the illegality

would still leave an adjudicative fact-finder convinced of the accused person's guilt." Id. at 168.

9. See, e.g., volf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25, 41 (1949) (Murphy, J., dissenting).

1o. "In theory the Crime Control Model can tolerate rules that forbid illegal arrests, unreasonable searches, coercive interrogations, and the like. What it cannot tolerate is the vindication of

those rules in the criminal process itself through the exclusion of evidence illegally obtained or

through the reversal of convictions in cases where the criminal process has breached the rules laid

down for its observance." H. PACKER, supra note I, at 167-68.

ii. N. MoRRIs & G. HAWKINS, TE HONEST POLITICIAN'S GuIDE To CRMEs CONTROL 3-4 (1970).

It is interesting to note that both Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914) (lottery tickets), and

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (g6x) (obscene materials), involved prosecutions for nonvictim crimes.

x2. The matter is actually somewhat more complex. A nation which does not respect individual

privacy might still have a nonvictim crime problem if it did not have sufficient police resources to

enforce a code of morality. Conversely, a nation with both a respect for individual privacy and a

May 19741

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY RULE

state is the absence of nonvictim crime--or, put another way, the rigid

morality enforced by the state upon its citizenry.

It is difficult to state the exclusionary rule with great precision. In most

cases, it makes inadmissible in a defendant's criminal prosecution any evidence seized in violation of his constitutional rights." Yet when needed to

impeach the defendant's testimony at trial, evidence unconstitutionally

seized from him is admissible.' 4 And the fact that evidence illegally seized

from one person may sometimes be admissible against another leads us

directly into the morass of deciding who has standing to assert the rule.'

The difficulty in defining the scope of the exclusionary rule, however,

should not mask its importance. The fact remains that in a very large category of cases, evidence in the government's possession which may show

that a defendant has committed a crime cannot be used because it has been

illegally obtained by the police.

It is not my thesis here that the exclusionary rule should be abandoned.

Rather, it is that the exclusionary rule, as Professor Packer said of the criminal sanction itself, is "needed but nonetheless lamentable."' 6 Professor

Packer's view on the shaky justifications for the criminal sanction accounts

for his careful attention to its appropriate limits. Similarly, attention should

be directed to the appropriate limits of the exclusionary rule.

This Article asserts that (i) the exclusionary rule does not have such an

honorable or ancient lineage that it should be maintained without reference

to the validity of its justifications;17 (2) demonstrations of the value or cost

of the exclusionary rule in utilitarian terms are singularly unpersuasive; 8

(3) the political price of the rule is extremely high-so high in fact as to

jeopardize its existence, regardless of its presumed benefits;19 and (4) two

modifications may be made in the rule which would lower its political price

and, with respect to one at least, have promise of considerably increasing its

efficacy in protecting constitutional rights."

I. THE JUSTIFICATION OF THE EXCLUSIONARY RULE

The argument for the exclusionary rule must stand or fall simply on the

basis of its demonstrated utility. Its proponents gain no strength-indeed

shortage of police resources could eliminate the existence of nonvictim crimes simply by decriminalizing those offenses for which the criminal sanction is inappropriate.

13. See Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914).

14. See, e.g., NValder v. United States, 347 U.S. 62 (1954) (testimony relating to illegally

seized heroin used to impeach defendant's statement that he had never possessed any narcotics).

15. See, e.g., Brown v. United States, 411 U.S. 223 (1973); Alderman v. United States, 394

U.S. 165 (1969); Jones v. United States, 362 U.S. 257 (i96o).

16. H. PACKInt,supra note i, at 6i, quoting Vasserstrom, Why Punish the Guilty?, UNIVERSITy,

Spring 1964, at 14.

17. See text accompanying notes 21-35 infra.

18. See text accompanying notes 36-5o infra.

19. See text accompanying notes 51-75 infra.

20. See text accompanying notes 94-115 infra.

1030

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[VOL. 26: Page

IO27

they are weakened-by reference to fundamental constitutional implications, well-established traditions, or universalities of adoption such as are

sometimes relevant to other legal arguments.

Entirely apart from the case that may be made for or against the exclusionary rule, its restriction is hardly a radical step. First, the exclusionary

rule does not "look" like a constitutional doctrine. Courts could make a

direct connection to fourth amendment values by holding that the government is not permitted to benefit from the fruits of an unconstitutional

search and seizure. Yet the exclusionary rule does not fully adhere to this

tenet. The rule is limited by such constructs as standing,21 the attenuation

of taint from illegal searches,22 and the admissibility of illegally seized

evidence for impeachment." Moreover, if courts strictly enforced the notion that the government could not benefit from an illegal search and seizure by its police officers, we would return to persons subjected to an illegal

search the contraband seized from them-presumably giving them a headstart with their heroin, sawed-off shotguns, or stolen property.2 '

The fact that courts have not done so indicates that the exclusionary rule

is merely one arbitrary point on a continuum between deterrence of illegal

police activity and conviction of guilty persons. As a stopping point, it can

be justified solely on the ground that it achieves a better balance between

these twin goals than would other points. If another stopping point does

the job better, it should replace the current exclusionary rule.

This type of "quasi-constitutional" law is not unique to the fourth

amendment area. The Supreme Court recognized in Miranda25 that the

prohibitions it had laid down would stand unless and until an equally good

method of protecting the constitutional values in question was developed.

In other words, the rule is not written into the Constitution. Rather, the

Constitution demands something that works-presumably at a reasonable

social cost. The content of the particular remedial or prophylactic rule is

thus a pragmatic decision rather than a constitutional fiat.

In addition, the rule was not adopted by the United States Supreme

Court until 1914.28 While it is certainly possible that an interpretation first

See cases cited note 15 supra.

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963).

23. Walder v. United States, 347 U.S. 62 ('954); cf. Harris v. New York, 401 U.S. 222 (1971).

24. For two interesting fact situations rejecting such severe remedies, see Frisbee v. Collins, 342

U.S. 529 (1952) (murder conviction affirmed; court refused to free defendant even if he were illegally kidnapped by Michigan police in Illinois and forcibly taken across border to stand trial), and

Welsh v. United States, 220 F.2d 2oo (D.C. Cir. 1955) (money illegally seized and suppressed in

numbers game prosecution; court retained money subject to determination whether defendant owed

federal taxes for the undeclared income).

25. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

26. See Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914). Iowa was the only state which had

applied the exclusionary rule prior to Weeks. See State v. Sheridan, 121 Iowa 164, 96 N.W. 730

(1903). For a compilation of states adopting the exclusionary rule as of 1949, see Wolf v. Colorado,

388 U.S. 25, 34 table 1 (1949).

2X.

22.

May 1974]

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY RULE

made 125 years after a constitutional provision might nonetheless be an appropriate one," the time lag between the adoption of the fourth amendment

and the first appearance of the exclusionary rule is at least some indication

that it was hardly basic to the constitutional purpose.

Furthermore, the exclusionary rule was not imposed upon the states

until 196i, and then by a divided Supreme Court." Moreover, there was an

extensive period when the exclusionary rule was in effect in some states and

not in others,)" and there is certainly no convincing demonstration that

individual liberties were any better protected in the former than in the

latter. For example, there is not even a hint that civil liberties were better

protected in Illinois, which applied the exclusionary rule,"0 than in Massachusetts, which did not."

It is also worth noting that the United States is the only nation that

applies an automatic exclusionary rule. 2 Perhaps this is an appropriate response to uniquely American conditions. Our nation is more heterogeneous

than most developed countries-ethnically, economically, and culturallya fact which perhaps lessens citizen identification with the minority groups

whose privacy is most often invaded by the police. Furthermore, the United

States does not have a tradition of control of the police by the central government. Such control by the executive, whatever its dangers, places less of

a burden upon the judiciary. It also may be that the United States has the

most moralistic and puritanical system of criminal law," which requires

police efforts at enforcement that place special strains upon their respect

for the privacy of citizens. Finally, Americans may simply be less upset by

police intrusions than are citizens of other countries and thus less willing to

enforce the guarantees of privacy through political means or even as jurors.

The fact remains, however, that there are many other countries which do

not have a mandatory exclusionary rule but which seem to be at least as able

as we to prevent their police from intruding upon the rights of citizens. " In

27. Cf. Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (954); Erie R.R. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S.

64 (1938).

28. See Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (196i); cf. Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 23 (1963).

29. By 1949, 31 states had rejected the exclusionary rule and 16 had adopted it. Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25, 38 table I (i949).

392, 143 N.E. 112 (1924), cited in Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S.

30. People v. Castree, 311 Ill.

25,36 table F (1949).

31. Commonwealth v. Wilkens, 243 Mass. 356, 138 N.E. ii (x923), cited in Wolf v. Colorado,

338 U.S. 25, 37 table G (1949).

32. By 1949, the io British Commonwealth jurisdictions which had considered the exclusionary

rule had rejected it. Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25, 39 table J (i949). For a discussion of attitudes

toward the exclusionary rule in several major countries, see The Exclusionary Rule Under Foreign

Law, 52 J. CRim. L.C. & P.S. 271-92 (i96i). An argument can be made that since 1961 Italy has

adopted a modified form of the exclusionary rule. See Trihbunale of Imperia, 74 Giustizia Penale 363

(1969).

33. See N. MoRsS &G. HAWMNS, supra note ii, at 1-28.

34. See The Exclusionary Rule Under Foreign Law, supra note 32. For a discussion of the

Canadian experience, see Oaks, Studying the Exclusionary Rule in Search and Seizure, 37 U. Cm.

L. REv. 665, 70--o6 (1970), and authorities cited id. at 702.

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[VOL. 26: Page

102 7

fact, their leading legal representatives express in private, and occasionally

in public, a complete mystification that the United States would adopt a rule

which deprives the prosecution of reliable evidence of guilt." In other

words, the exclusionary rule is hardly a facet of American jurisprudence

which has aroused admiration the world over.

II. THE

UTmiTA iAN ARGUNENT

One might therefore ask with some skepticism what justifies this unique

rule. It is not reassuring to relate that the major argument adopted by the

Supreme Court for the exclusionary rule is that nothing else works." This

reasoning reminds one very much of the old vaudeville skit about the drunk

looking for his keys under a light post. When questioned he admitted that

he had lost the keys some blocks away but argued that it made no sense to

look there because it was far too dark. One may tend to forget that just because nothing else works does not justify adopting an alternative which does

not work either.

Comparing the methods of enforcing the fourth amendment guarantees

is unnecessary, however. There is no point here in discussing the mass of

literature which describes the ineffectiveness of the threat of civil damages

or of criminal prosecution in compelling police obedience to the fourth

amendment." No one has proposed to do away with civil "8 or criminal 9

sanctions, however chimerical they are in practice. It is the exclusionary

rule which is under fire and it is this we must examine.

The fundamental criticism of the exclusionary rule is that, as structured

today, its benefits in protecting the privacy of the citizen are outweighed

by its associated costs in political hostility and reduced crime control. Few

would disagree that as a device to deter police illegality, the exclusionary

rule has fallen far short of its goal. There is evidence that the exclusionary

rule is very often blunted in practice because the police, unrestrained by

lower court judges who find the facts, successfully commit perjury to uphold the legality of their searches."0 Moreover, even in those cases where

the evidence is suppressed, the policeman typically does not find out about

35. See, e.g., remarks of Lord Widgery, Lord Chief Justice of England, American Bar Association Convention, July x6, 1971, reported in N.Y. Times, July 17, 1971, at I, col. 3.

36. See Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961).

37. E.g., Edwards, Criminal Liability for UnreasonableSearches and Seizures, 41 VA. L. REv.

621 (955); Foote, Tort Remedies for Police Violations of Inditidual Rights, 39 MINN. L. REv. 493

(z955); Symposinm-Police Tort Liability, 16 CLEV.-MAR. L. REv. 397-454 (1967).

38. 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (970). For judicial discussion of civil sanctions, see Bivens v. Six Unknown

Named Agents, 403 U.S. 388 (971); Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (0946).

39. 18 U.S.C. §§ 241-42 (1970).

40.

See, e.g., P. CHEVIGNY, POLICE POWER 187-88 (1969); J. SscoLNics,

JUSTiCE wITHouT TRIAL:

LAW ENFORCEMENT IN DFMocaRA-c SocIaTY 214-15 (x966); Oaks, supra note 34, at 739-42; Comment, Effect of Mapp v. Ohio on Police Search-and-Seizure Practicesin Narcotics Cases, 4 CoLum. J.L.

&Soc. PROB. 87,95 (1968).

May 1974]

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY RULE

the matter. The crucial assumption of feedback to the police is simply belied

by experience in most, if not all, police departments.

The prevalence of the guilty plea also weakens the threat of excluding

evidence at trial. The pressures and inducements to plead guilty in modern

urban criminal systems are enormous.4 In those jurisdictions which do

not permit appeals from search and seizure decisions following a guilty

plea,' there is simply no review of the operation of the exclusionary rule

in approximately 9o percent of the criminal cases.4" In these cases, the likelihood of eventual suppression of crucial evidence is not enough to make the

risk of going through a trial worthwhile. The possible vindication on appeal after trial becomes merely one factor to be weighed in the bargaining

by prosecutors and defense attorneys; the likelihood of the defendant's remaining in jail pending trial and the possibility of a more severe sentence

upon conviction after trial must also be taken into account.

In addition, complaints have been made that the legal doctrine the rule

enforces is so complicated and abstruse that the police often honestly and

reasonably cannot determine in advance what a majority of the Supreme

Court will later find to have been the doctrine's command." Perhaps most

importantly, it has been argued that the rule is ineffective because the police

are not ordinarily motivated by the search for admissible evidence. Indeed,

the threat to exclude evidence leaves untouched a myriad of police activities

such as peacekeeping, harassment of offenders, and many intelligence activities which do not and are not intended to lead to admissible evidence in

a criminal case. "

Certainly, the empirical studies to date support the view that the impact

of the exclusionary rule on the policeman's on-the-street behavior is minimal!' Nevertheless, the rule does seem to have some effect on police behavior. According to Professor Jerome Skolnick,47 for example, the police

do pay careful attention to the laws concerning search and seizure in

planning large-scale gambling raids which they expected to result in major

41. Kaplan, The Guilty Plea, STANFORD MAGAZINE, Fall-Winter 1973, at 50.

42-. See, e.g., Tollett v. Henderson, 411 U.S. 258 (i973).

43. Annual Report of the Director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts for

the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, X972, at 394 table D7 (i973). See generally D. NEWMAN, CONvicTioN-THE DETERMINATION oF GUILT OP INNOCENCE WITHOUT TRIAL (I966).

44. See Burger, Who Will Watch the Watchman?, 14 AM. U.L. REv. I, ii (z964); Burns,

Mapp v. Ohio: An All-American Mistake, '9 DEPAuI L. REv. 8o, xoo (1969); LaFave, Search and

Seizure: "The Course of the Trie Law . . .Has Not . . .Run Smooth," 1966 ILL. L.F. 255; Oaks,

supranote 34, at 731-32.

45. See, e.g., Barrett, PersonalRights, Property Rights, and the Fourth Amendment, 196o SUP.

CT. REV. 46, 54-55.

46. See, e.g., LaFave, Improving Police Performance Through the Exclusionary Rule-Part I:

Current Police and Local Court Practices,30 Mo. L. REv. 391 (1965); Oaks, supra note 34; Spiotto,

Search and Seizure: An EmpiricalStudy of the Exclusionary Rule and its Alternatives, 2 J. LEGAL

STUDIES 243 (1973); Comment, Search and Seizure in Illinois: Enforcement of the Constitutional

Right of Privacy, 47 Nw. U.L. REv. 493 (952).

47. J.SKOLNICK, supranote 40, at 212-29.

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[VOL. 26: Page 102 7

criminal prosecutions. It is also true that neither the district attorney's

office nor the police department of Los Angeles, for example, paid any attention to the commands of the fourth amendment until the adoption of

the exclusionary rule forced them at least to consider the parameters of an

unconstitutional search and seizure. 8

Calculation of the costs of the exclusionary rule are even more difficult

to make. Undeniably, the exclusionary rule allows some criminals to escape

punishment. Perhaps for many persons, this is a sufficient reason to discard

the rule. A more sophisticated analysis, however, reveals certain problems

with such a view. First, it completely neglects the value of the rule, which

even if negligible must at least be considered. Second, it does not account

for the fact that the cases invoking the exclusionary rule disproportionately

involve nonvictim crimes, where the case for criminal punishment tends

to be weaker." And finally, over a wide range of crimes the efficacy of

punishment is by no means certain. Indeed, Professor Packer pointed out

that a major support for the due process model derives from "a mood of

skepticism about the morality and utility of the criminal sanction taken

either as a whole or in some of its applications. ' ' "° Yet skepticism is not total

disbelief. As long as the criminal sanction retains some utility, its weakening

through the exclusionary rule is a cost to society.

Yet one may dispute this proposition as well. The fact that deterrence

generally increases with the number of persons convicted does not mean

that it does so proportionately. Empirical observations may show that while

deterrence is great where convictions are many and small where convictions are few, the change in deterrence is minimal in many places in between these poles. More precisely, assume that the number of crimes is a

function of the number of convictions. The number of crimes may vary

enormously at extremes, so that a ioo percent chance of conviction might

produce noticeably fewer crimes than a 99 percent chance. And a zero

48. Compare People v. Cahan, 44 Cal. 2d 434, 445, 282 P.ad 905, 9ii ('955), with Parker,

POLICE 117, cited in Paulson, The Exchionary Rule and Misconduct by the Police, 52 J. Came. L. &

P.C. 255 n.3 (1961).

49. There are certainly a few areas, primarily involving nonvictim crime, in which the use of

the criminal law is so grossly inappropriate that even the roughest calculation will reveal costs con-

siderably exceeding benefits. See, e.g., J. KAPLAN, MARIJUANA-THE NEw PRoHIBIIor (197o). Yet

it cannot be said that nonvictim crime must always be relatively trivial or that such laws always fail

to command strong public approval. See text accompanying note io9 infra.

50. H. PACKER, supra note I, at 170. Professor Packer characteristically understated the matter

when he referred to mere skepticism. Others have gone further and have reached the conclusion that

the criminal sanction is unjustifiable both in utilitarian and moral terms. Professor Paul Bator

has phrased this criticism well: "[W]e are told that the criminal law's notion of just condemnation and

punishment is a cruel hypocrisy visited by a smug society on the psychologically and economically

crippled; that its premise of a morally autonomous will with at least some measure of choice whether

to comply with the values expressed in a penal code is unscientific and outmoded .... Bator, Finality

in Criminal Law and FederalHabeas Corpus for State Prisoners, 76 HARv. L. REv. 441, 442 (1963),

cited in H. PACKER, supra note I,at 170.

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY

May 1974]

RULE

1035

conviction rate might result in many more crimes than a one percent rate.

Nonetheless, the amount of deterrence may vary very little along the domain of an intermediate number of convictions. If this is so, then releasing

a few more criminals will have little effect on deterrence.

This argument, however, is based on two hypotheses: that such an intermediate domain exists in which the change in deterrence with increasing

punishment is minimal and that present rates of punishment are on that

domain. Because neither of these assumptions is necessarily true, the conclusion that the exclusionary rule does not reduce deterrence of crime is

highly speculative at best.

Others argue that the exclusionary rule does not significantly affect society's interest in isolating dangerous individuals. They think unimportant

the relatively small number of such individuals freed by the exclusionary

rule, especially compared with the substantial number at large in the population at any one time. Even granting the validity of this claim, one still

reasonably might respond that the release of even one dangerous person

is a cost to society.

Finally, one must acknowledge that the exclusionary rule often allows

a criminal to escape punishment. Though one may scoff at the need for

retribution as irrational, hypocritical, and old-fashioned, it seems to lie deep

within the human psyche. The frustration of a popular need for retribution

is another factor that must be considered in making a utilitarian calculation

of the cost of the exclusionary rule.

III. Tim

PoLIcIAL PicE oF THE ExcLusioNARY RULE

The criminal system, therefore, is a political necessity in any democratic

country even if its costs and benefits cannot be calculated in a convincing

way. In fact, the political requirement of punishment for the sake of felt

justice indicates that something resembling our present criminal system

would survive a convincing demonstration that its utilitarian justifications

are inadequate and that criminals could be handled in nonpunitive ways.

It is precisely this feeling of justice that is outraged when an obviously

guilty person is released through application of the exclusionary rule. Unlike procedural protections such as the rights to counsel and to a fair trial,

which can be defended as preconditions to a reliable factfinding process,

the exclusionary rule lessens the probability of a rational determination of

guilt. The solid majority of Americans rejects the idea that "[t]he criminal

is to go free because the constable has blundered."51 Indeed, this public

dissatisfaction has recently become a major political force. Public opinion

5x. People v. Defore, 242 N.Y. 13, 21, 15o N.E. 585, 587 (1926) (Cardozo, J.).

io36

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26: Page 1027

polls have shown an extremely high rate of disapproval of the courts for

their role in "coddling criminals,""2 and the prototype of these complaints

is enforcement of the exclusionary rule.

Popular hostility toward the rule arises from much more than the fact

that it interferes with our punishing people we regard as guilty. The disparity in particular cases between the error committed by the police officer

and the windfall given by the rule to the criminal is an affront to popular

ideas of justice. Indeed, this lack of proportionality demonstrates why the

exclusionary rule cannot be justified as a moral imperative preventing the

courts from soiling themselves with tainted evidence. 3 Proportionality is

a major element of our sense of justice. The lack of proportionality between

the crime and the punishment was shocking when Jean Valjean received

what amounted to a life sentence for stealing a loaf of bread, 4 and a similar

sense of injustice arises from the disparity between the police officer's error

and the failure because of it to punish one who has committed a serious

crime. One can, of course, conceive of many trivial police errors in the search

and seizure area that may end in the acquittal of guilty and, more significantly, dangerous persons. For instance, the police practices revealed in

Coolidgev. New Hampshire" are hardly incompatible with a moral society;

yet letting the defendant in that case go free perhaps is.

It is undeniably true, however, that in practice the exclusionary rule

rarely allows dangerous defendants to go free. In serious cases, there are

often other charges not weakened by the exclusionary rule, or sufficient

evidence of the crime charged apart from that unconstitutionally seized.

Moreover, the courts have shown a remarkable ability in the most serious

cases to stretch legal doctrine to hold doubtful searches and seizures legal.

The courts have often avoided applying the exclusionary rule in situations

in which the consequences of so doing would offend their own sense of

proportionality or reach beyond their view of what the public would toler52. GALLUP OPINION INDEx, REP. No. 45, at 12 (1969). Of those sampled, 2% thought that

courts deal too harshly with criminals; 75% thought that courts are not harsh enough.

53. One can admittedly defend the proposition that the exclusionary rule serves the interest

of judicial integrity over and above the interests of the particular defendant and of the deterrent

effect on police violations of constitutional rights. The rule, however, has been so justified by only

three Justices. See United States v. Calandra, 94 S.Ct. 613, 624 (1974) (dissenting opinion). Moreover, in actual operation, the rule would seem to injure judicial integrity far more than it serves

that end. And finally, any moral end that is served in the name of judicial integrity must be

balanced against our sense of injustice not only at letting a serious criminal go free, but at letting

him go free because of what may be a trivial error by the police.

54. V. HUGO, LEs MISgRABLES. Although his case is often cited as an example of draconian

punishment, jean Valjean actually received only a relatively short sentence for the theft. The conditions of his imprisonment then drove him to attempt escapes which resulted in his further punish-

ments.

55. 403 U.S. 443 (971) (conviction for "particularly brutal" murder of 14-year-old girl reversed on fourth amendment grounds; evidence from police seizure and subsequent search of defendant's parked car unconstitutionally obtained, where search warrant defective since not issued by

neutral magistrate, and search not within any recognized exception to warrant requirement).

May 1974]

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY RULE

ate. It is very hard to believe, for example, that the decision in Abel v. United

States" would have been reached by the Court in any case other than one

involving a Russian spy. One cannot know, of course, whether the Court

was more influenced by the lack of proportionality itself or by its fears of

adverse public reactions to the obvious amusement which would pervade

the Kremlin if one of its chief spies were acquitted on the basis of an American constitutional right completely alien to Soviet jurisprudence.

In Wayne v. United States, 7 where a dead body was found illegally, the

relatively liberal Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia refused

to order its suppression, on the theory that it eventually would have been

discovered legally. The problem with this reasoning, of course, is that it

would make the exclusionary rule inapplicable to a high proportion of

presently unconstitutional searches and seizures. The decision should not

be particularly surprising, since courts often stretch and strain in serious

cases to avoid applying the exclusionary rule."

Such decisions may actually lower any adverse impact of the exclusionary

rule on crime control. But since the reasoning behind them is unacknowledged, covert, and usually disingenuous, public dissatisfaction with the rule

is not reduced. The exclusionary rule is still viewed as a statement that

evidence will be suppressed no matter how slight the police error in seizing

it (providing the error is of a constitutional dimension) and no matter how

crucial it is to conviction. It is not surprising that the rule's political price is

quite high.

Probably the major reason for the high political price of the exclusionary

rule is that, by definition, it operates only after incriminating evidence has

already been obtained. As a result, it flaunts before us the costs we must

pay for fourth amendment guarantees. Of course, the command of the

fourth amendment itself contemplates less than complete efficiency in criminal law enforcement. The problem is that the exclusionary rule rubs our

noses in it. In contrast, a sanction which actually prevents police violations

of the fourth amendment would permit many criminals to remain free

who would be caught either in a society which had no fourth amendment

rights or in a society, such as ours, where the rights are observed so imperfectly. Where guarantees of individual rights are actually obeyed by the

56. 362 U.S. 217 (ig6o). The Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, affirmed the conviction of

Rudolph Abel for conspiracy to commit espionage. The Court held a warrantless search of Abel's hotel

room by the FBI valid because Abel had abandoned the property. The only problem with the use of

the abandonment doctrine in this case is that Abel "abandoned" the hotel room only after being

arrested by federal authorities armed only with an administrative warrant for deportation. In his dissent Justice Brennan noted: "This is a notorious case, with a notorious defendant. Yet we must take

care to enforce the Constitution without regard to the nature of the crime or the nature of the

criminal." Id. at 248.

57. 3x8 F.2d 205 (D.C. Cir. x963).

58. I personally have never known of a case where a dead body was ultimately ordered suppressed.

io38

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26: Page 1027

police, criminals are not discovered and thus no shocking cases come to

public consciousness. When we apply the exclusionary rule, however, we

know precisely what we would have found had constitutional rights been

violated (because, of course, in these cases they were violated), and we

are forced to witness the full, concrete price we pay for these guarantees.

It is true that many criticisms of the exclusionary rule mask fundamental objections to the rights it protects." One does not have to oppose fourth

amendment values, however, in order to object to the exclusion of evidence.

There are many cases where police have both the cause and the opportunity

to get search warrants but fail to do so. Sometimes a warrant is obtained but

subsequently held to be defective. And often the police fail to knock appropriately before making an otherwise legal search. In these situations, it

is probable that the criminal would have been caught even if the police had

followed fourth amendment requirements." It is in such cases that application of the exclusionary rule is most clearly a windfall to the criminal.

The political price of the exclusionary rule, it should be made clear, is

not limited to the silent majority. The police also believe the rule is illegitimate and, as a result, it lacks the moral sanction which is so important to

effective deterrence. It is true that the police often do not hold the requirements of the fourth amendment itself in great esteem-in part because of

their very complexity; in part because they are seen to be made by judges

who have little conception of reality on the streets; in part because they

are so easy to evade; and in part because they so often are the result of

split decisions among judges all of whom, the police feel, should know

the law equally well 1 There are many other reasons rooted in the police

force's organizational structure and the policeman's conception of his role

which lead him to regard the constitutional restraints upon him as illegitimate.9 There are, however, degrees of illegitimacy, and the exclusionary

rule is regarded as even less legitimate than the restraints it is intended to

enforce. The result is that a substantial percentage of policemen take the

view that two wrongs make a right and that perjury is a permissible method

of avoiding the sanction.63 In addition, many trial judges, who are generally

59. E.g., Inbau, Public Safety v. Individual Civil Liberties: The Prosecutor'sStand, 53 1. Capm.

L.C. & P.S. 85 (x962); Statement of Chief of Police of Los Angeles, L.A. Times, Apr. 28, 1955,

cited in Barrett, Exclusion of Evidence Obtainedby Illegal Searches-A Comment on People v. Cahan,

43 C.LIF. L. Rav. 565, 567 (1955).

6o. Compare Sibron v. New York, 392 U.S. 40 (1968) (frisk without reasonable suspicion;

heroin found in defendant's pockets), and Davis v. Mississippi, 394 U.S. 72X (1969) (detention

without probable cause; incriminating fingerprints taken), with Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403

U.S. 443, 449-55 (197) (search warrant issued by prosecutor; neutral magistrate available), and

Spinelli v. United States, 393 U.S. 410 (1969) (affidavit underlying search warrant invalid because

unreliable; facts showing informant's reliability presumably could have been stated).

61. See J.SKOLNICK, supra note 40, at 2X2-29.

62. See W. LAFAvE, ARREST: THE DEcIsION TO TAKE A SUsPer Iro CUSTODY 210-I (1965);

J. SKoNICK, supra note 40, at 219-29.

63. See generally J. WAmBAuG5H, THE BLUE KNIrr 178-220 (972), and sources cited note 40

supra.

May 1974]

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY RULE

1039

less removed than the Supreme Court from popular opinion and the political process, share police attitudes. At best they are ambivalent, and in

many cases they are eager to believe the police where doing so will prevent

the imposition of the exclusionary rule.6"

As a result, the United States Supreme Court is under constant pressure

to shape its substantive rules in order to minimize the number of opportunities for sabotage by the lower federal and state judiciaries through their

control of factfinding. The effect of this pressure has been most dramatic

in the fifth amendment area. There the Supreme Court repeatedly was

presented with findings of voluntary confessions in situations where the

records made coercion quite likely. Powerless to overturn such findings of

fact, the Supreme Court stretched the definition of coercion to include the

lower courts' factual determinations. As a result, the Supreme Court found

coercion in progressively less aggravating situations." Gradually this procedure became almost as disingenuous as the lower courts' decisions.

In the fourth amendment area the best example of this process does not

come from the Supreme Court, but from the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, one of the relatively few intermediate appellate courts

which vigorously enforces the exclusionary rule. In a number of cases, police

had justified otherwise illegal searches on the basis of a consent which was

hotly denied by the defendant. The court of appeals accepted the lower

courts' factual determination that the policeman had told the truth, but

ordered exclusion of the evidence by applying a definition of consent

which was at best artificial. In Judd. v. United States,"6 for example, the

court distinguished true consent from "the false bravado of the small time

criminal."

In both the fifth and the fourth amendment contexts, the pressure on

appellate courts to prevent lower court sabotage has disturbed the nature

64. See Amsterdam, The Supreme Court and the Rights of Suspects in Criminal Cases, 45

N.Y.U.L. R:Ev. 785, 792 (970).

65. Compare Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278 (936) (confession made following hanging

from a rope and repeated whipping held involuntary), with Haynes v. Washington, 373 U.S. 503

(1963) (confession made following 16-hour incommunicado detention held involuntary), and Greenwald v. Wisconsin, 39o U.S. 519 (1968) (confession made x2 hours after arrest, during which

time defendant was questioned periodically, held involuntary). For a more complete development of

this thesis, see Amsterdam, supra note 64, at 803-1o.

66. 19o F.2d 649, 651 (D.C. Cir. x951). The defendant was arrested on suspicion of grand

larceny, and police questioned him in jail. They asserted that he had volunteered his consent to their

searching his apartment for evidence of the crime. Despite the defendant's denial of the police version

of the conversation, the judge believed the police, held consent had been given, and refused to exclude

the incriminating evidence found. The police testified that "he said he had nothing to conceal or hide

out there, and it was perfectly all right for us to go out there." Id. at 650.

In reversing the trial court, the court of appeals took note of the remarks of the trial judge:

"The two police officers impressed the Court as gentlemen of probity. The defendant is unworthy

of belief, because of his past conflicts with the law.

"He certainly is not entitled to ask the Court to accept his word as against officers of the law."

Id. at 652 n.8. The court refused to overturn the findings of fact, but did not interpret them as consent.

See also Higgins v. United States, 2o9 F.2d 819 (D.C. Cir. 1954).

1040

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[VOL. 26:

Page 1lO27

of the rules applied. The result, however, has been rules which are less defensible on rational grounds and thus less acceptable to both police and the

public.

Probably the most important political price inherent in the administration of the exclusionary rule, however, is simply that the Supreme Court

is only temporarily isolated from public opinion. Whether it is true in the

words of Finley Peter Dunne that "the Supreme Court follows the election

returns,"67 it is clear that the Presidents who appoint Supreme Court Justices follow the election returns.68 Before his appointment, our present Chief

Justice had publicly called for the restriction and eventual abolition of the

exclusionary rule." It is fairly clear that this position, together with his related attitudes on crime control, was a major factor in his attractiveness to

the President."0 His and other appointments were defended as an effort to

give a kind of balance to the Court on crime control versus due process

issues7 So far as the exclusionary rule was concerned, however, it did not

appear to be balance that the President was seeking, but rather the victory of

crime control values. For the time being, the exclusionary rule has escaped

destruction at the hands of the appointment process, but only the greatest

accidents of fate have allowed its survival. Had fate decreed that two additional vacancies appear on the Supreme Court before Watergate and its related imbroglios, the exclusionary rule already could have met a swift and

untimely end. For the present it probably is protected not only by a majority

of the present Supreme Court,;2 but also by a considerable weakening of the

President's power to work his will through the appointment process.

Actually, the results of Watergate have been quite complex. It has caused

those in power, who had won their mandate in great part on a law and

order ticket, to reexamine the premises of their own views. As of the 1972

elections, it would have been inconceivable for then Vice President Agnew

to denounce publicly what he felt to be government excesses in overreaching

an accused. Interestingly, the two major examples of overreaching he cited,

the promise of immunity to prosecution witnesses and the fact that a pro67. F. DUNNE, MR. DOOLEY ON THE CHOICE OF LAW 52 (compiled by E. Bender i963).

68. See L. KOHLMEIER, JR., GOD SAVE THis HONORABLE COURT: THE SUPREME CoURT Cuss

(1972); Kahn, On the Appointment of Justices to the Supreme Court (Book Review), 26 STAN.

L. Rav. 689 (i974).

69. See Burger, supra note 44. The Chief justice has reiterated these views in Supreme Court

opinions. See Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, 403 U.S. 388, 411-24 (971)

(dissenting

opinion).

70. N.Y. Times, May 22, 1969, at i, col. 8; id., May 23, 1969, at x,col. i.

7x. Id., May 23, 1969, at x, col. i.

72. Justices Douglas, Brennan, and Marshall have indicated their satisfaction with the exclusionary rule. For a recent expression of their view, see United States v. Calandra, 94 S. Ct. 613, 624 (1974)

(Brennan, J., dissenting). Justices White and Stewart have been reluctant to overturn or restrict past

decisions, even those with which they originally disagreed. See, e.g., Kirby v. Illinois, 4o6 U.S. 682,

705 (1972) (White, J., dissenting).

May 1974]

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY RULE

1041

spective defendant has no right to cross-examine witnesses before a grand

jury,'" are both practices as old as the Republic. Presumably they were

known to the Vice President since his bar examination days and were entirely unobjectionable until he himself became a prospective criminal defendant.' Similarly, the President's dedication to the rights of privacy

would have seemed equally incomprehensible at the time of his enormous

mandate, and it is fairly clear that he, too, has had second thoughts about

the rights of the criminal defendant.

We should not forget, however, that the events of the past year have been

more than unusual in our constitutional history. If the exclusionary rule is

temporarily safe, the political unpopularity of the rule remains; it is likely

that with another one or two swings of the pendulum, it will be in great

jeopardy again.

IV.

PROPOSED

MODIFICATIONS

OF THE EXCLUSIONARY RULE

The present exclusionary rule, therefore, has many obvious and serious

defects. Increasing attention is being given to its future. The remainder of

this Article will be devoted to exploring the modifications that might profitably be made in the rule.

A. The Amsterdam Suggestions

In his recent Holmes Lectures, my colleague, Anthony Amsterdam, has

suggested a number of major changes in our whole way of looking at the

fourth amendment. He has suggested, for instance, that the basis of fourth

amendment interpretation be changed from an atomistic view, which asks

whether the particular rights of the individual defendant have been violated, to a regulatory view, which asks whether the police practice in question, taken as a whole, is unreasonably intrusive. As a result, he would

expand the exclusionary rule to cover those cases where the particular individual taking advantage of that rule had not himself suffered an unconstitutional search or seizure. 6

Secondly, Professor Amsterdam would use the exclusionary rule as a

prophylactic measure to confine a legitimate police practice to its theoretical

justification. He would, therefore, apply the rule not only to punish police

who had behaved improperly, but also to make sure that there is no incentive for them to do so." Thus, if police observed a sawed-off shotgun on

73. N.Y. Times, Oct. x6, 1973, at 34, col. x.

74. Compare statements made by Mr. Agnew during the 1968 campaign. Id., Sept. 16, 1968, at

x6, col. i.

75. 1974 State of the Union Address, reprinted in id., Jan. 31, 1974, at 20, col. I.

76. Amsterdam, Perspectives on the Fourth Amendment, 58 MINN. L. REv. 349, 367-72 (1974).

77. Id. at 433-38.

1042

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[VOL. 26:

Page 102 7

the floor of an automobile during a legitimate vehicle stop for a license

check, the evidence would be suppressed. The reason for this would not

be to punish the police for behaving improperly, but rather to assure that

their decisions to institute license checks would not be tainted by any impermissible motive.1 8 Similarly, Professor Amsterdam would restrict the admissible evidence produced by a stop-and-frisk to that related to the only theoretical ground for the police practice-a search for weapons. For example,

if the "hard object which felt like a weapon" turned out to be a container of

heroin, it would be suppressed not because it was found illegally, but because otherwise the police would have an incentive to frisk when they were

not in fact concerned about weapons."9

Professor Amsterdam's suggestions are administrable and thoughtful

answers to the problem of insuring privacy and preventing evasion of fourth

amendment commands. In both cases, however, they seem politically impossible to implement. The trend is in quite the opposite direction. It is likely

that no matter how well articulated and argued such propositions might be,

they simply could not secure the consensus which would be required not

only for adoption by the Supreme Court but also for lasting public acceptance. It is difficult enough to apply the current formulation of the exclusionary rule to let an apprehended criminal escape justice where the police

have done something wrong and where the defendant's rights have been

violated. Where neither is the case, the political costs of the exclusionary

rule simply price it out of the market. Indeed, the society enlightened

enough to apply such rules might not need an exclusionary rule at all.

Professor Amsterdam's most significant suggestion, however, raises a

more complicated issue. He urges that the fourth amendment be held to

require the police to develop departmental rules governing the activities

of its officers in the search and seizure area. 0 Starting with Professor Kenneth Culp Davis, a number of commentators have underlined the importance of written police rules in the governance of police conduct.8 Certainly,

such rules are enormously important in restraining the police. There is

no doubt that the adoption of detailed departmental rules of police conduct

78. Id. at 438.

79. Id. at 436-38.

8o. Id. at 4s6-3s.

81. See, e.g., K. DAvis, DIscREIoNARY JusrIE-A PRELIMINARY INQUIRY (971); McGowan,

Rule-Making and the Police, 70 MiCH. L. Rav. 659 (1972); Wright, Beyond Discretionary Justice

(Book Review), 8i YAaE L.J. 575 (x972).

82. Professor Amsterdam lists many advantages of a requirement of rules promulgated by the

police. These include the following: (I) it provides a pervasive safeguard against arbitrary searches

and seizures without creating new exceptions to the fourth amendment, (a) it generates none of the

problems of unclarity and unintelligibility which plague a graduated fourth amendment, (3) it

would restrict the proliferation of police practices which arise in part out of a desire to avoid courtmade rules, and (4) it would permit courts to extend the coverage of the fourth amendment to police

activities which require controls other than warrants and probable cause requirements. Amsterdam,

rupranote 76, at 418-22.

May 1974]

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY RULE

in the search and seizure area would considerably help control police misbehavior and protect fourth amendment values. Since Professor Amsterdam

is the first person to have suggested that the fourth amendment commands

the promulgation of such rules, it is hard to predict whether his suggestion

will soon be adopted. In our jurisprudence, where many extremely important decisions are already made by judges far from the political arena, the

very fact that a sweeping principle is completely new may be enough to

doom it, at least for awhile."3 On the other hand, it certainly is not beyond

the realm of possibility that federal legislation could be passed imposing

such a requirement upon the police. Whether or not the drawing of rules

in this area is required by the fourth amendment, the suggestion is certainly

related closely enough to the enforcement of constitutionally protected

values to make the requirement of police rules an appropriate subject for

congressional legislation under section five of the L4 th amendment."'

How then would the requirement of police regulations affect the exclusionary rule? Professor Amsterdam comprehends that a search and seizure

made in violation of the commands of the police regulations would itself

lead to the exclusion of evidence." Since presumably conduct which is

presently illegal would not be legalized even under appropriate regulations,

evidence would be excluded in an additional category of cases. Such a solution, however, might only aggravate the problem. Even though police regulations, drafted and publicized, would almost inevitably produce some

improvement in police behavior in the search and seizure area, litigation

over their meaning and applicability could produce an even more complicated morass than at present. Regulations, at least in their early years, would

often be extremely vague and subject to differing interpretations. In addition, the regulations inevitably would fail to cover certain unanticipated

situations or else simply contain errors. Anyone who has attempted to start

almost from scratch to draft disciplinary regulations for a university or to

bring law to any area in which it has not developed over the years knows

how difficult and fraught with error the job is.8" These caveats do not argue

against drafting police regulations; they merely emphasize that expanding

the exclusionary rule to cover conduct violative of the regulations would

only increase an already excessive strain upon the rule.

83. The recent rejection of a constitutional attack on school financing is just one example of

this phenomenon. See San Antonio Indep. School Dist. v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973).

84. Cf. Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970); Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (x966).

In these two cases, the remedies referred to rights explicitly granted by the x4 th amendment. Whether

§ 5 extends to rights which are incorporated in the 14 th amendment is still unsettled. Since the

exclusionary rule is designed as a remedy against police abuses, however, it seems particularly suited

to the purposes of § 5. Of course, it is by no means certain that such a legislative intrusion into police

governance ispolitically feasible today.

85. Amsterdam, supra note 76, at 416-3i.

86. Cf. Linde, Campus Law: Berkeley Viewed from Eugene, 54 CALIF. L. REv. 40 (x966).

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[VOL. 26: Page

10:27

B. The InadvertenceTest

What then can be done to ease the burden on the exclusionary rule while

still attempting to protect fourth amendment values? One superficially

tempting modification would be to hold the rule inapplicable where the

constitutional violation by the police officer was inadvertent." The exclusionary rule, we are usually told, is intended to deter violation of constitutional rights by police.88 Presumably, a policeman will be deterred either

because the rule simply informs him that there is no point in conducting

an illegal search and seizure or because the department will turn its anger

on him for allowing a criminal to go free. 8 If these are the reasons for the

exclusionary rule, it makes little sense to apply it to cases in which the policeman did not know his violation was illegal." Moreover, if one regards the

exclusionary rule as a moral imperative, it certainly seems less of one where

the policeman's offense is inadvertent and hence less culpable.

There are, however, basic problems with such a modification of the rule.

It would put a premium on the ignorance of the police officer and, more

significantly, on the department which trains him. A police department

dedicated to crime control values would presumably have every incentive

to leave its policemen as uneducated as possible about the law of search and

seizure so that a large percentage of their constitutional violations properly

could be labeled as inadvertent. Nor would it suffice further to modify the

rule and require that the police error be reasonable as well as inadvertent.

While such a standard would motivate a police department to insure that

its officers made only reasonable mistakes, it is hard to determine what

constitutes a reasonable mistake of law. Moreover, the exclusionary rule is

already held inapplicable where a policeman makes a reasonable factual

mistake. 1

87. I use inadvertent to refer to those actions which the police do not know are illegal at the

time they commit them. This terminology should not be confused with the type of inadvertence

defined by Justice Stewart in Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443, 469-73 (1971): the police

had been sufficiently unaware of the existence of items seized in a plain view search that their failure

either to get a warrant for them or to describe them in a warrant already obtained did not amount to

avoidance of fourth amendment requirements. Obviously, this situation is entirely different from one

in which the police were unaware of the illegality of their action.

88. See, e.g., Elkins v. United States, 364 U.S. 206, 217 (ig6o): "The rule is calculated to

prevent, not to repair. Its purpose is to deter-to compel respect for the constitutional guaranty

in the only effectively available way-by removing the incentive to disregard it."

89. See, e.g., Elkins v. United States, 364 U.S. 206, 217 (I96O); Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S.

25, 47 (1949) (Murphy, J., dissenting).

9o. Courts generally do not focus upon the policeman's inadvertence. Yet this consideration

may be viewed as a sub silentio basis for the Supreme Court's opinion in Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S.

293 (1967). The usual rule in nonretroactivity cases makes the relevant date that of the trial itself,

irrespective of when the police practice in question occurred. See, e.g., Johnson v. New Jersey, 384

U.S. 719 (x966). By holding in Stovall that the rules announced applied only to those lineups conducted after the date of decision, the Court implied that police knowledge of the illegality of the

lineup is an important factor. See Schaefer, The Fourteenth Amendment and Sanctity of the Person,

64 Nw. U.L. Rav. 1, 15-17 (i969).

gi. E.g., United States v. Robinson, 94 S. Ct. 467 (i973) (hard object seized during a traffic

May 1974]

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY RULE

1045

There is a more serious problem with exempting searches made through

inadvertent errors of law from the exclusionary rule. To do so would add

one more factfinding operation, and an especially difficult one to administer, to those already required of a lower judiciary which, to be frank, has

hardly been very trustworthy in this area. It is difficult enough to administer

the current exclusionary rule, since police perjury can, and often does, prevent accurate findings of fact." So long as lower court trial judges remain

opposed on principle to the sanction they are supposed to be enforcing, the

addition of another especially subjective factual determination will constitute almost an open invitation to nullification at the trial court level. In

order to suppress evidence, the trial judge would have to find a deliberate

constitutional violation, and evidence of the officer's state of mind would

be generally difficult to come by apart from the officer's self-serving and

generally uncontradicted testimony. And since the necessary finding requires proof that a policeman actually has engaged in a criminal act, the

defendant's burden of proof would be increased, as a psychological or perhaps even as a legal matter."

C. Two PracticalModifications

There are two ways, however, in which reduction in coverage will improve the exclusionary rule. The first is aimed primarily at reducing the

political and enforcement costs of the exclusionary rule. The second is

much more complicated and is directed toward increasing the benefits of

the rule in reducing the number of fourth amendment violations in our

society. These two modifications are independent, so that a disagreement

with one does not require rejection of the other.

For those who are wedded to the present rule, and even more for those

who would expand it, any restriction would be a retreat in the face of the

enemy, a cutting back when it is most necessary to hold firm.94 A cutting

back of the exclusionary rule, however, can also be regarded as a pruning,

a method of making it more acceptable and hence more lasting; it is indeed a method of giving more, not less, protection to fourth amendment

values.

arrest and subsequent search for weapons held admissible, although actually a cigarette package containing heroin); see text accompanying note 79 supra.

92. See sources cited note 40 supra.

93. It is always easier to convince jurors that a person's illegal action was inadvertent than it is

to convince them it was purposeful. See R. KETON, TRiAL TAcaics AN MEaos 291-92 (2d ed.

1973). This is particularly true when the actor is a police officer. The defendant's burden might be

increased even as a matter of law. For example, the burden of proof to justify a warrantless search is

on the prosecution. If the defendant must show that the police have engaged in a criminal act in conducting the search, then the burden of proof would shift to the defendant. See CAL. Evro. CODE § 520

(West x966).

94. See text accompanying note 117 infra.

io46

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26: Page io27

The "seriouscases" exception.

The first proposed modification of the exclusionary rule is a simple one.

It would provide that the rule not apply in the most serious cases-treason,

espionage, murder, armed robbery, and kidnaping by organized groups.

Even in such cases, some police violations would still invoke the exclusionary rule. The Rochin v. California'sstandard would still survive, so that

evidence would be suppressed if the violation of civil liberties were shocking enough. The modified exclusionary rule, then, would at least preclude

exclusion of evidence where the police misconduct was far less serious than

this. It may be, however, that a set of "core" rules, more specific than the

Rochin test, could be developed, violations of which would lead to invocation of the exclusionary rule. Yet under either variation, the mere fact of

a fourth amendment violation would not require the exclusion of evidence

in the relatively small class of the the most serious cases.

One can, of course, argue against such a rule as unnecessary since the

courts are following it anyway," albeit covertly. Insofar as this is true, it is

a good reason for adopting the rule straightforwardly. For by purporting

to apply the exclusionary rule in all classes of cases without actually doing

so, the courts are paying the full political price without any real gain. Unfortunately, a major disadvantage of an empty threat is that sooner or later

its objects realize its hollowness. Finally, the lack of integrity inherent

in a false threat seriously weakens respect for the judicial process. On the

other hand, if the courts are in fact presently applying the exclusionary

rule to the most serious crimes, the political costs of the rule, the possibility

of releasing serious and dangerous offenders into the community, and

the disproportion between the magnitude of the policeman's constitutional

violation and the crime in which the evidence is to be suppressed are suffident reasons to modify the rule now.

The suggestion that the exclusionary rule not apply to the most serious

crimes is quite different from that made some 25 years ago by Justice Jackson in Brinegarv. United States." In his Brinegardissent, Justice Jackson

proposed that the content of police practices under the fourth amendment

should depend in part upon the crime under investigation. To use his example, an undiscriminating roadblock might be justified in searching for a

child-kidnaper, but never justified "to salvage a few bottles of bourbon." 8

Certainly, the purpose of the police is one factor in determining the reasoni.

95. 342 U.S. 165, 172 (1952) (police's illegally breaking into bedroom of defendant, struggling

to open his mouth to remove pills swallowed, and forcibly extracting his stomach's contents is "conduct that shocks the conscience").

96. But tee, e.g., Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443 (1971).

97. 338 U.S. 16o, i8o (1949) (dissenting opinion).

98. Id. at 183.

May 1974]

LIMITS OF EXCLUSIONARY RULE

ableness of their actions, and reasonableness implies a proportionality between means and ends. Yet the Supreme Court has never adopted Justice

Jackson's view, presumably because such a rule would raise grave problems

of administrability. Often the court would simply have to take the policeman's word as to what crime he was investigating. Administrative difficulties in the stop-and-frisk area illustrate this point. Regardless of what

they find, policemen almost always claim to be looking for weapons.99

The suggestion that the courts refuse to apply the exclusionary rule in the

most serious cases does not raise the same problem. All any court need do

to apply the variation suggested is to look at the crime charged.

There is admittedly one serious problem with this proposed modification of the exclusionary rule. Police departments, freed from the constraints

of the rule in the most serious cases, might actively encourage violation of

the fourth amendment. If so, the "core values" could be held to be violated

and the exclusionary rule applied. The invocation of the exclusionary rule

in such cases, however, may not be necessary. In investigations of the most

serious offenses, unlike the ordinary instances of police invasion of the citizen's fourth amendment rights in less serious cases, remedies other than the

exclusionary rule may be effective. The political consequences to the police

department, the threat of damage suits by large numbers of people against

top-level police officers,"' and the possibility of injunctive relief 10' might

well be at least as good a check upon this kind of wholesale police misconduct as is the present exclusionary rule.

It must frankly be admitted that the deterrent effect of such restraints

is a matter of conjecture. The effect of eliminating the exclusionary rule

in the most serious cases might possibly be to give the police somewhat more

liberty to violate the fourth amendment. Though such an effect, if it existed,

would be a serious disadvantage, it might still be preferable to the enormous

lack of proportionality and other costs evident in the present shape of the

exclusionary rule.

In addition, there are clear advantages in not applying the exclusionary

rule to the most serious crimes. Freed of the concern that the fourth amendment doctrine they announce would later result in the release of people

guilty of the most serious crimes, judges would be able to interpret more

fully and honestly the commands of the fourth amendment in all the remaining cases. Such a result would not be surprising. Increases in the range

of the exclusionary rule sanction tend to cause the contraction of the substantive rights protected. After Mapp v. Ohio,' for example, the Court

99. See, e.g., United States v. Robinson, 94 S. Ct. 467 (1973).

ioo. See 4 2U.S.C. § x983 (1970).

zoi. See, e.g., Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F.2d 197 (4th Cir. 1966).

102.

3

67U.S. 643 (196i).

STANFORD LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 26: Page 1027

seemed reluctant to expand the scope of the fourth amendment." 3 In fact,

Mapp's expansion of the exclusionary rule to include state as well as federal

enforcement officials arguably has produced a decrease in the kind of police

behavior held illegal.""

The application of a more stringent exclusionary rule to prosecutions

for certain crimes is different from the sliding scale model which Professor

Amsterdam discusses and then properly rejects. 0 5 Under that model, degrees of increasing governmental intrusion into an individual's privacy

must be supported by ever greater showings of cause. Professor Amsterdam

rightly dismisses this approach as unadministrable, at least in today's world

where we can hardly count upon full cooperation from the lower courts."'

Focusing, however, on the crime in which the exclusionary rule operates

is certainly no less and probably more administrable than our present exclusionary rule.

There are, moreover, several possible doctrinal rules one might adopt

concomitant with a decision not to apply the exclusionary rule in the most

serious cases. One could, for example, apply the rule more vigorously in all

the remaining cases. As a result, the constructs of standing and attenuation

of taint, which now operate almost randomly to narrow the exclusionary

rule, might be eliminated. Alternatively, one could divide the remaining

crimes into two categories: victim crimes, for which the present exclusionary rule would be retained; and nonvictim crimes, to which the application of the exclusionary rule would be more vigorous. As Professor Packer

has pointed out, in the nonvictim crime area police activity usually represents a considerably more significant intrusion into the privacy of the citIO3. See, e.g., United States v. Calandra, 94 S. Ct. 613 (1974) (witness may not refuse to

answer questions of grand jury on ground that questions are based on evidence illegally seized); Terry

v. Ohio, 392 U.S. i (1968) (warrant and probable cause requirements do not fully apply to stopand-frisk); Camara v. Municipal Ct., 387 U.S. 523 (1967) (specific probable cause requirement does

not apply to administrative inspections for housing code violations).

104. See, e.g., United States v. Robinson, 94 S. Ct. 467 (x973). See generally Ker v. California,

374 U.S. 23, 44 (1963) (Harlan, J., concurring).

io5. Amsterdam, supranote 76, at 376-77, 390-95.

io6. See text accompanying note 40 supra. Even more unadministrable and hence similarly to

be rejected is the solution suggested by the American Law Institute Model Code of Pre-Arraignment

Procedure.It suggests that the exclusionary rule not be invoked unless the violation is "substantial,"

and goes on to provide: "In determining whether a violation is substantial the court shall consider

all the circumstances, including:

(a) importance of the particular interest violated;

(b) the extent of deviation from lawful conduct;

(c) the extent to which the violation was willful;

(d) the extent to which privacy was invaded;

(e) the extent to which exclusion will tend to prevent violations of this Code;

(f) whether, but for the violation, the things seized would have been discovered; and