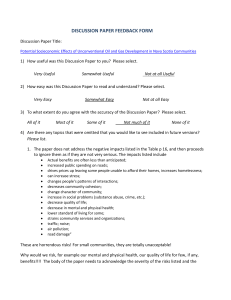

Aseel Rawashdeh United States Government 29311 Fracking Waste Safety Act: Bill Proposal & Research The name of my bill is the “Fracking Waste Safety Act”. The primary motivation for drafting this bill is my current HS Policy Debate topic, which is about the protection of water resources in the United States. I debated the impacts of fracking wastewater and methane leaks in many rounds and wanted to examine the currency political discussions around this issue. As a background, fracking is the process of pumping water mixed with special chemicals underground at high pressure to force out oil or natural gas. The problem is that these fluids, once they return to the surface, usually contain metals, dissolved solids, salts, and naturally occurring radioactive material [1]. This wastewater is usually left in designated pits or abandoned wells where it almost always infiltrates groundwater, aquifers, streams, or other aquatic habitats. This infiltration of water sources is detrimental to humans and wildlife, with chemicals resulting in health hazards and significant biodiversity loss. The EPA’s current regulations are vague and ineffective, allowing for many loopholes for polluters from the oil and gas industry, with non-punitive fines levied in cases when polluters are ‘held accountable’ [2]. Therefore, in this bill, I would like to propose the establishment of a national fracking waste disposal regulatory commission (abbreviated FWDRC). Because this bill recognizes the immensely hazardous--and sometimes radioactive--nature of fracking wastewater, the FWDRC will be modeled and modified based on the current (and, for the most part, successful) US government agency, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) established in 1974 to regulate nuclear waste disposal. Similar to the NRC, the FWDRC would also increase oversight, accountability, and monitoring in main three areas: 1) onsite fracking processes 2) fracking chemicals used (currently kept secret under trademark claims), and 3) transportation, storage, and disposal of fracking waste. Another similarity the FWRC would have to the NRC is establishing regional offices/headquarters in relevant locations. For example, fracking locations (and fracking accidents) are common in states like California, Colorado, North Dakota, Ohio, and Texas. Having several offices stationed a short distance from fracking sites combined with regular visits from trained compliance investigators deters polluters and decreases the likelihood of wastewater spills and methane leaks. Additionally, like the NRC and other regulatory agencies, individuals with a history working for (or having ties with) the oil and gas industry will not be appointed as investigators, board members, etc… to avoid bias from preventing accountability. Initially, I thought about making my bill just a ban on fracking (there was a congressional bill proposed by Rep. Ocasio-Cortez similar to this) but I figured that a comprehensive national ban on fracking will not be feasible soon (next 3-8 years), so a regulatory commission is the most pragmatic short term solution. 1 There has been a similar bill (H.R.436) proposed in the 116th congress in January 2019 by Rep. Darren Soto [D-FL]. It is called the ‘Fracking Disclosure and Safety Act’. H.R.436 eliminates specific exemptions for oil and gas operations from environmental requirements, such as requirements concerning stormwater runoff, hazardous air pollutants, solid waste disposal, and drinking water sources. Also, the bill requires the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to issue regulations governing the use of hydraulic fracturing under oil and gas leases for federal lands. Under this bill, the EPA must also issue a policy that adds hydrogen sulfide to the list of hazardous air pollutants and publish a list of categories of major sources and area sources of hydrogen sulfide (which includes oil wells) [3]. H.R. 436 was not passed in congress. Although H.R. 436 is similar to my bill in that it regulates fracking waste by eliminating loopholes for companies, my bill focuses on establishing a new commission dedicated specifically to fracking waste regulation called the national fracking waste disposal regulatory commission (FWDRC) as opposed to utilizing existing environmental regulatory agencies. The reason this is advantageous is that it centralizes the regulation of fracking waste disposal in one commission to avoid inefficiencies associated with working in a large and complex bureaucratic regulatory agency like the EPA, which is vital when dealing with hazardous and radioactive fracking waste. This method has proven effective in regulating nuclear waste with the establishment of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in 1974. When it comes to fracking oversight legislation, most support comes from the left. A good number of democratic representatives, such as Rep. Ocasio-Cortez, support a full fracking ban and have introduced such legislation into congress. In many cases, these representatives also vote for fracking regulation legislation when it is presented. Many Democrats are opposed to a full fracking ban, yet support tighter regulations on fracking waste; these include POTUS Biden, senator and chair of the Senate Rules Committee, Amy Klobuchar, and former representative, Beto O'Rourke [4]. On the other hand, republican party members tend to oppose any sort of federal oversight on oil and gas. Research by Wharton finance professor Erik Gilje has shown that shale booms tend to result in increased political power for the republican party, which of course, leads to increased fracking support by republican lawmakers [5]. Representatives and senators from states with a large fracking industry tend to support fracking the most. For example, Pennsylvania Sen. Gene Yaw, chair of the Senate Environmental Resources and Energy Committee, called the fracking industry ‘one of the most regulated in the United States [5]. Despite the positions of lawmakers on fracking, public support for fracking is tanking, and with it, popular support for regulations and oversight is increasing as reported by various public polls conducted by Gallup, the University of Michigan, and the Ohio River Valley Institute [6,7,8]. This comes as the public is learning more about the dangerous effects of fracking on the environment, public water, and air quality from popular media and news sources. In terms of interest groups, Americans Against Fracking (AAF; a national coalition of anti-fracking groups) is the most well-known interest group that supports fracking regulations and eventually phasing out/banning fracking. AAF cites the hazardous effects of fracking as a 2 justification for their position, arguing that climate-devastating methane, cancerous wastewater, and biodiversity loss are caused by poorly regulated fracking wells [9]. AAF organizes conferences centered around the national, state, and local fracking issues, such as a call to end fracking in Colorado. The AAF collaborates with groups like Local Control Colorado, which don’t advocate for a fracking ban, but “local control” and “regulation” of wells. On the other side, many interest groups oppose fracking regulations. Usually, these groups will argue that the benefits of fracking outweigh the risks, and regulations will deter the spread of fracking or lead to further restrictions or a future ban. The most common rallying point is the contribution of fracking to state economies, which makes fracking a big political issue in many state and national elections. Other argued benefits include a shift away from coal, increased job opportunities, and decreased water requirements compared to alternative fossil fuel production. The most common pro-fracking interest group is the Interstate Oil and Gas Commission (IOGCC), a self-proclaimed “government agency” that has played a tremendous role in blocking fracking regulation legislation [10]. The agency pays no taxes, registers no lobbyists, and regularly converses with policymakers. They take major contributions from the fracking industry. The IOGCC makes a big impact on fracking decisions nationally; it is made up of oil and gas lobbyists and executives as well as appointees from oil and gas producing states, usually the top oil and gas regulator from each state. These lobbyists and regulators meet multiple times a year at conferences funded by the fracking industry, where they write legislation together, which the state regulators take back to their states and pass into law. For example, in 2009, the IOGCC passed a resolution intended to keep Congress from overturning the Halliburton Loophole (a gap in the Safe Drinking Water Act that allows companies to inject toxic petroleum products without any permitting requirements or safeguards). Within a few months, ten states had passed resolutions mirroring the IOGCC’s language exactly. There are also many state-specific pro-fracking interest groups. In Texas, Texans For Natural Gas states that environmentalists against fracking are “extreme and fringe” and fear that regulations on the oil and gas industry will lead to a termination of fossil fuel use [11]. The courts have mostly only ruled on issues of fracking when it comes to local fracking bans and trespassing laws (i.e., companies drilling in surrounding land). However, in 2015, U.S. District Judge Scott Skavdahl in Wyoming struck down the Obama administration’s regulation rules for hydraulic fracturing on public lands [12]. Skavdahl ruled that the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lacked Congressional authority to set fracking regulations for federal lands. In other words, the issue before the court was not whether fracking oversight is good or bad, but whether Congress gave the Interior Department’s BLM legal authority to regulate the practice. The BLM’s proposed rules included a requirement for companies to provide data on chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing and to take steps to prevent leakage from oil and gas wells on federally owned land. Although this ruling struck down national fracking regulations, it was not a decision on their validity as much as their method of implementation (i.e., through the BLM). 3 In the discussion board, everyone who responded to my discussion post voted yes for my bill. They all agreed that the devastating effects of unregulated fracking on environmental and human health were terrible and needed to be addressed. Some students agreed with me that a fracking ban was necessary to make way for more sustainable renewable energy to fill in. Something interesting was that many students stated that they did not really understand what fracking was before they read my discussion post, indicating that there need to be more public education campaigns about fracking. Generally, people know of fracking, but don't understand the technical aspects of it and its harms. I think that in a real US Senate, this bill has a good chance (no guarantee) of passing. In January 2021, three new Democratic senators were sworn in, which resulted in 50 seats held by Republicans, 48 held by Democrats, and two held by independents (who tend to caucus with the Democrats). This basically created a 50–50 split, which had not occurred for almost two decades. However, with Vice President Kamala Harris serving as a tiebreaker in the Senate, the Democrats gained control of the Senate. With this democratic control, fracking regulations are more likely to pass given historical support for these policies from the left. Given that my bill only introduces regulations on fracking waste and no restrictions on the growth of fracking, there may be a few Republicans in the senate that support the bill (especially if they are not from fracking states) given public views on fracking. 4 Works Cited 1. Hammer, Becky. “Fracking's Aftermath: Wastewater Disposal Methods Threaten Our Health & Environment.” NRDC, Natural Resources Defense Council, 15 Dec. 2016, https://www.nrdc.org/experts/becky-hammer/frackings-aftermath-wastewater-disposal-m ethods-threaten-our-health-environment. 2. Morrison, Curtis. “Federal Fracking Waste Regulatory Commission, or Nah?” Vermont Journal of Environmental Law, VJEL, 2016, https://vjel.vermontlaw.edu/federal-fracking-waste-regulatory-commission-nah. 3. Soto, Darren. “H.R.436 - Fracking Disclosure and Safety Act.” Congress.gov, 1 Oct. 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/436?r=8&s=1. 4. Washington Post, Graphics. Fracking Ban: Where 2020 Democrats Stand, The Washington Post, 8 Apr. 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/politics/policy-2020/climate-change/fracking-b an/. 5. Gilje, Erik. “The Link between Fracking and Republican Power in Congress.” Knowledge@Wharton, 24 Mar. 2016, https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/the-surprising-link-between-fracking-and-re publican-power-in-congress/. 6. Lachapelle, Erick. “Public Opinion on Fracking: Perspectives from Michigan and Pennsylvania.” University of Michigan Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy, May 2013,https://closup.umich.edu/issues-in-energy-and-environmental-policy/3/public-opinio n-on-fracking-perspectives-from-michigan-and-pennsylvania. 7. de Place, Eric. “Public Opinion Is Moving against Natural Gas and Fracking.” Ohio River Valley Institute, 9 Aug. 2020, https://ohiorivervalleyinstitute.org/public-opinion-is-moving-against-natural-gas-and-fracki ng/. 8. Swift, Art. “Opposition to Fracking Mounts in the U.S.”, Gallup, 30 Mar. 2016, https://news.gallup.com/poll/190355/opposition-fracking-mounts.aspx. 9. BGR. “Americans against Fracking.” Big Green Radicals, 2013, https://www.biggreenradicals.com/group/americans-against-fracking-colorado/. 10. Coleman, Jesse. “Meet the Shadow Lobbyists Protecting Fracking from Regulation: The IOGCC.” Greenpeace USA, 4 Sept. 2018, https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/shadow-lobbyists-protecting-fracking-regulation-iogcc/. 11. TFNG. “Reports & Studies.” Texans for Natural Gas, https://www.texansfornaturalgas.com/messing_with_texas_study. 12. Bailey, David, and Ernest Scheyder. “Court Strikes down Obama Fracking Rules for Public Lands.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 22 June 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-fracking-injunction/court-strikes-down-obama-frac king-rules-for-public-lands-idUSKCN0Z81P7. 5