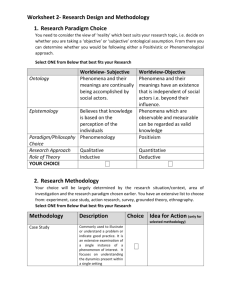

International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation Volume 8 • Issue 1 • January-March 2016 Grounded Theory and ActorNetwork Theory: A Case Study Bill Davey, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia Arthur Adamopoulos, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT This paper introduces a method of analyzing large text data in the context of an Actor-Network Theory based study. A case is used to illustrate conditions under which using an analytical technique from another philosophy seems particularly apt. A tool commonly used in Grounded Theory was applied in a manner aimed at facilitating a search for potential actors and their interactions and for evidence of specific translations of the innovation in the case used. Keywords Actor-Network Theory, Bitcoin, Case Study, Grounded Theory INTRODUCTION Those of us with an interest in Actor-Network Theory (ANT) find it easy to gain adherents to the idea of our world being formed through the interactions of socio-technical actors – there seems to be a natural resonance with the ideas of ANT in qualitative researchers. A problem that becomes apparent when one is dealing with these “new adherents” is that ANT is an “approach” rather than a method. “ANT is a material-semiotic approach for describing the ordering of scientific, technological, social, and organizational processes or events.” (Wickramasinghe, Tatnall, & Bali, 2010, p. p8). Once the ANT approach has been chosen, the next stage of applying the ideas to a research project often starts with the question, “what do I DO?” This question might be answered with intellectual honesty with “it depends on what the question is.” A quick look at relatively recent studies shows that various combinations of theoretical viewpoint and analysis technique have been used in interesting ways by those taking an ANT approach. Passoth and Rowland (2010) use state theory to define different types of Actor-Network theory outcomes. Both Fleischmann (2006) and Kéfi and Pallud (2011) use analysis steps from Grounded Theory to analyse interview data that produces an outcome familiar to ANT readers. Hedström (2007) commences a study using case studies, treating each case through the lens of Actor-Network theory and analyses the interview data using Grounded Theory methods. Although these methods include mixtures of analytical technique and new philosophical positions, there seems to be a growing desire to make explicit some methods used for identifying meaning in the data. That is, to make explicit the activities undertaken by the researcher in arriving at a conclusion. This desire is motivated by those seeking to increase trust in qualitative outcomes and those seeking to involve new researchers in ANT studies. The case of a recent convert to ANT may be of value in this discussion. This paper uses the example of a specific study to guide discussion of the nature of a question that might benefit using analysis techniques from Grounded Theory. DOI: 10.4018/IJANTTI.2016010102 Copyright © 2016, IGI Global. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited. 27 International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation Volume 8 • Issue 1 • January-March 2016 THE CASE The research team in this case was interested in the adoption of Bitcoin. The authors decided that the approach to understanding this adoption would involve identifying the important actors and their interactions and determining the nature of the translation of digital currency that came into being. This innovation is interesting as it has developed into a medium of exchange for those wishing to trade in illegal goods, but also as a speculative currency with the advantage of being almost a pure market driven currency. Having decided that Actor-Network Theory was the most appropriate approach to this question, some research design decisions were made that make this project an interesting basis for discussion. It was decided that the data most likely to lead to understanding was not the post-facto interviewing of people today, but the examination of web-based sources. Web based sources are interesting as they are statements and opinions of some historical ‘fact’ frozen in time, rather than reflective reports filtered by the need to meet publication standards. Blogs and online articles are a discourse online – a type of conversation. The research team examined a vast array of blogs, websites, commentary and news articles. As the sources were archived at the time of production, they allow the picture of the network forming in time to be captured and analysed. This source of data, and its size, is a unique aspect of the sample study. A limitation of web-based data is that it cannot be interrogated, nor can new statements be generated by asking new questions of the website (as is available with a live interview). Bitcoin as a topic of the study brings with it research questions of a particular nature. Firstly, the entire history of the innovation is short, recent and intensely studied. The origin of Bitcoin is attributed to a person using the name Satoshi Nakamoto (who has still not been traced to a real person and is possibly a fictitious name) who uploaded a white paper to the Internet in 2008 (Nakamoto, 2008). The innovation is almost completely online, although the physical conversion of Bitcoins to other currencies was available from 2010 (Yermack, 2013). The scrutiny of Bitcoin is intense, partly because the possibility exists for disruption of global currency markets with an alternative unregulated by any government or organization that could be easily controlled (Böhme, Christin, Edelman, & Moore, 2015). Bitcoin was adopted by various groups in very different ways: both legal and illegal. This is recognized by the wide differences in legal approach: from patents to make the coin legal in some way (Guthrie, 2014) through to attempts to stop illegal use of the currency (Slattery, 2014). These aspects of the topic invited the research team to think in terms of different translations and to seek to identify the actors involved and the interactions that formed possible stable networks supporting those translations. THE ACTOR-NETWORK LENS Passoth and Rowland (2010), and many others, have identified that ANT is described by researchers in different ways and many methods have been used under this banner. Passoth and Rowland (2010) make a distinction between those researchers who seek to understand the nature of the actors in the network and those researchers who seek to understand the nature of the network. One might characterize these as those searching for the particular and those searching for the general. The “particular” would be intent on identifying who were actors with strong interactions and the detail of the translation that became stable. The “general” would seek to understand the network as a whole. A quick perusal of the Actor-Network Theory literature shows a continuum between those intent on the particular and those determined to understand the general. The particular might focus on the nature of actors and their interactions, and the general are more interested in understanding the story revealed by the research. This can be seen in the beginnings of ANT in the differences between the studies of (Latour, 1996) 28 International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation Volume 8 • Issue 1 • January-March 2016 and (Callon, 1986). In the case of this study, the researchers were intent on identifying the sociotechnical actors, the strength of their interactions and the nature of the translation(s) of the innovation. This is a specific interpretation of ANT and the comments made here should be seen in this light. GROUNDED THEORY AND A.N.T. This paper is not suggesting an amalgamation of two research philosophical approaches. A brief representation of Grounded Theory will be discussed with the intention of showing our view of the differences, rather than educating the reader in an alternative qualitative approach. For a proper description of Grounded Theory, refer to Strauss and Corbin (1998). Grounded Theory and Actor-Network Theory can be seen as co-habiting the space of Phenomenology, in that both acknowledge the power of examining the perceptions of humans to shed light on a world “directly experienced” (Heidegger, 1988; Husserl, 1970). Both Grounded Theory and ANT include the assumption that “all my knowledge of the world, even my scientific knowledge, is gained from my own particular point of view, or from some experience of the world…” (MerleauPonty & Smith, 1996). It is at this point that Grounded Theory and ANT diverge. Two key theoretical concepts that are fundamental to Grounded Theory analysis are those of objectivity and sensitivity. Objectivity means maintaining an objective stance when analysing the data. “In qualitative research, objectivity does not mean controlling the variables. Rather, it means openness, a willingness to listen and to ‘give voice’ to respondents” (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In this case, respondents are usually only humans. The researcher taking a Grounded Theory approach seeks only to be “sensitive” to the meaning within the data – presuming only that this can be sensibly related to the researcher’s life experience. The researcher has prior knowledge that is not simply put aside but instead acknowledged and understood so as to better uncover the concepts in the data. “There is a difference between an open mind and an empty head” (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). This acceptance of the involvement of the researcher in the data analysis is part of the process, but the process also seeks to make sure that meaning is not missed. This is done through “coding.” The key task of analysis in Grounded Theory is one of coding data into concepts, categories and themes. A concept is a labelled phenomenon (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Elements in the data are broken down into discrete incidents, ideas, events and acts and are given a name. The name may be one placed on the objects by the analyst, or the name may be taken from the words of the respondents themselves, known as in-vivo codes (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The analysis begins with what is known as ‘Microscopic Examination of Data’, which is “the detailed line-by-line analysis necessary at the beginning of a study to generate initial categories (with their concepts and themes) and to suggest relationships among categories; a combination of open and axial coding’ (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The initial interviews are analysed line by line and any concepts of interest are identified and coded. This is the step called “open coding.” This is followed by “axial coding”. The purpose of axial coding is to begin the process of reassembling data that were fractured during open coding. In axial coding, categories are related to their subcategories to form more precise and complete explanations about phenomena (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The basic tasks of axial coding include (Strauss, 1987): • • • • Laying out the properties of a category and their dimensions, a task that begins during open coding. Identifying the variety of conditions, actions/interactions and consequences associated with a phenomenon. Relating a category to its subcategories through statements denoting how they are related to each other. Looking for cues in the data that denote how major categories might relate to each other. 29 International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation Volume 8 • Issue 1 • January-March 2016 It is not until the major categories are finally integrated to form a larger theoretical scheme that the research findings take the form of a theory. Selective coding is the process of integrating and refining categories. Concepts that reach the status of a category are abstractions; they represent the stories of many persons reduced into several highly conceptual terms. They should have a relevance for, and be applicable to, all cases in the study (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). This process seeks to develop a theory as closely as possible from the data – theories “grounded in the data.” By contrast, ANT starts from beliefs about the way the world works. ANT researchers look for meaning arising from socio-technical actors and look for evidence of those actors and the interactions between them. They are also bound by the data but look for patterns in the data that “listen” to both human and non-human actors. AN ANALYTICAL APPROACH INSPIRED BY GROUNDED THEORY The researchers gathered an enormous quantity of textual data from the Internet and saw a problem in absorbing all the data. The quantum of the data was so large that even a team of researchers would have been tempted to identify sources corresponding with their predetermined biases. This was particularly tempting as there have been histories of the adoption of Bitcoin and the researchers were familiar with the themes of those histories. As the team were familiar with a standard tool used for Grounded Theory that could deal with large amount of text, it was decided to enter all the data into that tool, which can be done automatically, and to use the tool in a constrained way. The very large dataset was loaded into the tool and analysis commenced using a variation on the analysis method that would normally be used in Grounded Theory. The key task of analysis in grounded theory is one of coding data into concepts, categories and themes. In this case we were not interested in general concepts but in identifying only indications of the existence of an actor, the interactions of the actors and clues as to the relationships between actors and possible translations of Bitcoin. Our “in-vivo codes” were to be those we identified as actors, interactions or aspects of the translation. The initial stage of Grounded Theory analysis is open coding, described in the previous section. This first step was performed by the team, taking separate blocks of documents and trying to identify, in an open way, anything that might later become an actor, an actor interaction or an aspect of the translation. The “openness” was only expressed by a determination to not censor ourselves as to potentially strong or weak evidence, but to quickly record all ‘candidates’. The next stage of Grounded Theory analysis is axial coding. In our case, the next stage, supported by the software we used, was to look at the initially coded actors, interactions and translations and find properties and interrelationships between the ‘candidates.’ If an actor was found often and with similar interactions described by different sources, then it became more likely to be a final rather than a candidate. Themes were initially ascribed to potential translations, and each potential aspect of a translation assigned to each theme. Themes with coherent properties became strong candidates for a description of a final translation. As we used a team to perform these tasks it was possible for each final statement of actor and interaction, and each set of properties of a final translation, to be examined by a team member not involved with the initial identification. The team felt that this process provided significant value to the final outcome. The usual goal of coding in Grounded Theory analysis is to develop a unified theory as the outcome. In our case, we were not interested in new theories but in identifying the specific ANT inspired aspects of the innovation of Bitcoin: actors, interactions and translations. 30 International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation Volume 8 • Issue 1 • January-March 2016 CONCLUSION The study that was used as the basis of this discussion has specific characteristics. The research was designed with a very specific outcome in mind: determining actors, interactions and their relationship with the various translations. The data consisted of a very large block of text rather than interviews. In interviews the data is “mutable” to the extent that the interview can be directed according to information within the interview. Historical text is obviously a special type of data and not often the basis for ANT studies. The particular case is one which has been discussed widely and about which histories have been written. This last peculiarity raises the potential problem of the research team being overwhelmed by the quantity of data and unconsciously using a technique to filter the data for concepts “known” to be true. The use of the Grounded Theory tool is unique. We used the tool not to search for the traditional themes and theories of Grounded Theory but to search for socio-technical actors and information about the interactions of the actors. This gave us the confidence those actors and interactions exist in the data and, if they contradicted histories, that it would be possible for us to find them. Although silly to generalize from this one case, the research team found that this way of approaching a very large dataset allowed us to “accumulate” a picture of the network that arose to support the innovation. The accumulation happened as each member of the team coded different pieces of data for the predetermined and restricted themes of actor, interaction and translation, allowing more of a “team” effort than is normally associated with methods where the researcher becomes “immersed” in the data. This picture of the network differs from the traditional histories in interesting ways in that it is based on commentaries, each of which was frozen in time through the Internet archiving process. 31 International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation Volume 8 • Issue 1 • January-March 2016 REFERENCES Böhme, R., Christin, N., Edelman, B., & Moore, T. (2015). Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(2), 213–238. doi:10.1257/jep.29.2.213 Callon, M. (1986). The Sociology of an Actor-Network: The Case of the Electric Vehicle. In M. Callon, J. Law, & A. Rip (Eds.), Mapping the Dynamics of Science and Technology (pp. 19–34). London: Macmillan Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-07408-2_2 Fleischmann, K. R. (2006). Boundary objects with agency: A method for studying the design–use interface. The Information Society, 22(2), 77–87. doi:10.1080/01972240600567188 Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter. Guthrie, N. (2014). The End of Cash? Bitcoin, the Regulators and the Courts. Banking & Finance Law Review, 29(2), 355–367. Hedström, K. (2007). The values of IT in elderly care. Information Technology & People, 20(1), 72–84. doi:10.1108/09593840710730563 Heidegger, M. (1988). The basic problems of phenomenology (Vol. 478). Indiana University Press. Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy. Northwestern University Press. Kéfi, H., & Pallud, J. (2011). The role of technologies in cultural mediation in museums: An Actor-Network Theory view applied in France. Museum Management and Curatorship, 26(3), 273–289. doi:10.1080/096477 75.2011.585803 Latour, B. (1996). Aramis or the Love of Technology. Cambridge, Ma: Harvard University Press. Merleau-Ponty, M., & Smith, C. (1996). Phenomenology of perception. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Consulted, 1(2012), 28. Passoth, J.-H., & Rowland, N. J. (2010). Actor-network state integrating actor-network theory and state theory. International Sociology, 25(6), 818–841. doi:10.1177/0268580909351325 Slattery, T. (2014). Taking a Bit out of Crime: Bitcoin and Cross-Border Tax Evasion. Brooklyn Journal of International Law, 39(2), 44. Strauss, A. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/ CBO9780511557842 Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. Wickramasinghe, N., Tatnall, A., & Bali, R. K. (2010). Using Actor-Network Theory to facilitate a Superior Understanding of knowledge Creation and knowledge Transfer. International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation, 2(4), 42. doi:10.4018/jantti.2010100104 Yermack, D. (2013). Is Bitcoin a Real Currency? An economic appraisal. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 19747. doi:10.3386/w19747 32 International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation Volume 8 • Issue 1 • January-March 2016 Bill Davey is a Senior Lecturer at RMIT University in Australia. Bill has published over 100 papers in a range of information systems related topics varying from design methods to applications. He is currently researching aged care with colleagues in the United States and hospital systems in Australia and Germany. Bill is particularly interested in Actor-Network theory and Phenomenography as research methods for uncovering explanations for uptake of technology and the conceptual frameworks that are formed by people using technology. Dr Arthur Adamopoulos is a Lecturer in the school of Business Information Technology and Logistics at RMIT University in Australia. He is currently researching the adoption and usage of technologies in a range of contexts including Online Investing, eHealth, Cloud Computing and Crypto Currencies. 33