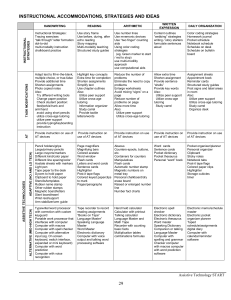

Crossing the Age Divide: Cross-Age Collaboration Between Programs Serving Transition-Age Youth Maryann Davis, PhD Nancy Koroloff, PhD Kathryn Sabella, MA Marianne Sarkis, PhD Abstract Programs that serve transition-age youth with serious mental health conditions typically reside in either the child or the adult system. Good service provision calls for interactions among these programs. The objective of this research was to discover programmatic characteristics that facilitate or impede collaboration with programs serving dissimilar age groups, among programs that serve transition-age youth. To examine this Bcross-age collaboration,^ this research used social network analysis methods to generate homophily and heterophily scores in three communities that had received federal grants to improve services for this population. Heterophily scores (i.e., a measure of cross-age collaboration) in programs serving only transition-age youth were significantly higher than the heterophily scores of programs that served only adults or only children. Few other program markers or malleable program factors predicted heterophily. Programs that specialize in serving transition-age youth are a good resource for gaining knowledge of how to bridge adult and child programs. Address correspondence to Maryann Davis, PhD, Transitions to Adulthood Center for Research, Systems and Psychosocial Advances Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 222 Maple Ave., Shrewsbury, MA 01545, USA. . Kathryn Sabella, MA, Transitions to Adulthood Center for Research, Systems and Psychosocial Advances Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Shrewsbury, MA, USA. Nancy Koroloff, PhD, Regional Research Institute, School of Social Work, Portland State University, PO Box 751, Portland, OR, USA. Marianne Sarkis, PhD, International Development and Social Change, Global and Community Health Program, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA. ) Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 2018. 356–369. c 2018 National Council for Behavioral Health. DOI 10.1007/s11414-018-9588-9 356 The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 45:3 July 2018 Introduction An estimated 3.8 million 15–25-year-olds (aka transition-age youth) in the USA are living with serious mental health conditions.*1–3 Transition-age youth with serious mental health conditions often struggle to complete their high school education,4–6 enroll and complete college,7–9 and establish adult work lives.10 They are also at high risk for homelessness,11, 12 justice system involvement,13, and cooccurring substance use disorders14 and commonly receive services in multiple public child and adult systems such as mental health, justice systems, foster care, or vocational rehabilitation. These service systems are often organized by the age group of the target population they serve. For example, child welfare services are typically provided up to age 18 or 21 years15 while adult mental health services are offered to those 18 and older.16 Therefore, services that transition-age youth encounter are found in both child and adult systems, and for 18–21 year olds, often in both simultaneously. In addition to adult and child systems serving different target populations with different eligibility criteria,16 variable funding streams, accountability structures, different service Bcultures,^ and different staff training backgrounds17 produce further system fragmentation. As a result, strong collaboration between these different services is needed to most effectively serve transition-age youth, to coordinate services when both systems are involved, to facilitate transition from child to adult services, to reduce gaps and redundancies in services, and to prevent service dropout. Unfortunately, the coordination among and transition between child and adult systems is not easy.18 More broadly, services can improve and benefit when child and adult systems work together, such as exchanging expertise that one system has and the other needs. For example, family involvement during young adulthood can be critically important to young adult success yet it is quite complicated. Child mental health providers have expertise in engaging or partnering with families that could help inform adult programs on how to maximize age-appropriate family support for young adults.19, 20 Conversely, adult mental health services have expertise supporting individuals’ vocational goals,21, 22 which could help inform child systems working with older adolescents who want to work. For these and additional reasons, it is important to support and foster more cross-age collaboration, i.e., collaboration between two programs that serve different age groups that could include transition-age youth. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) acknowledges the need to promote collaboration across child and adult services to improve the system that supports transition-age youth with serious mental health conditions (e.g., SAMHSA RFA No. SM-1401723). Based on this need, SAMHSA has initiated three separate grant programs that encourage grantees to promote collaboration across child and adult services: the Partnership for Youth Transitions (2002–2006), the Emerging Adult Initiative (2009–2014), and the Now is the Time Healthy Transitions program (2014–2019). The evaluation of the Partnership for Youth Transitions initiative documented success in the development of program models; findings suggested that interorganizational collaboration, especially among providers of adult and child mental health services, was potentially key to positive outcomes.24 Yet, little is known about the types of programs that collaborate across this particular age divide and the malleable program factors (i.e., those that can be changed) associated with greater cross-age collaboration. Knowledge from collaboration in other sectors can inform our understanding of what types of programs may collaborate well across this particular age divide and the potential malleable program factors associated with greater cross-age collaboration. One factor identified as contributing to health/human services collaboration is program specialization. Generalist and specialist programs can serve a similar population but generalists, unlike specialists, offer This figure is calculated from the 12% prevalence rate of serious emotional disturbance for children and adolescents1 applied to population of 15–17-year-olds and 6.5% prevalence rate of serious mental illness2 applied to the population of 18–25-year-olds from in the 2016 U.S. Census population estimate.3 * Cross-Age Collaboration DAVIS ET AL. 357 comprehensive services to the same population in-house minimizing their need to refer clients to outside sources. Generalist organizations tend to be bigger, have more resources, and serve more clients than specialist organizations. They tend to be more central to the network of organizations serving a population by serving a brokerage or linking role with other resources in the network.25 On the other hand, organizations may be more specialized by virtue of the population they serve, by their capacity, or the focus of their treatment (e.g., small residential treatment program for 16– 21-year-olds). Specialized organizations tend to be more limited in resources and will refer clients to bigger and more generalized organizations as a way to best benefit their clients. Thus, specialist programs may collaborate more because other organizations have resources their organization or clients need. Moreover, limitation in any single aspect of a program’s scope (e.g., funding level, number of clients, and array of services) is one of the main predictors of the types of linkages that organizations maintain with other organizations.25, 26 Other researchers have found that collaboration occurs when it is needed to meet client needs26, 27 and that reciprocal connections are often based on exchanges or competition. For example, connections may be forged in order to obtain funding or specific services that are needed to provide improved services or to fulfill a contractual obligation. Perceptions that collaboration is expected can also increase collaborative behavior.28 Thus, a program’s perception that clients will benefit from cross-age collaboration or that a funder requires cross-age collaboration should result in enhanced cross-age collaboration. Contractual or funding obligations that also include requirements for collaboration may increase program collaboration efforts. Other research in a variety of organization types (e.g., education, manufacturing, human service29–32) has described other mechanisms that foster collaboration and system change that might be present in programs that collaborate more. These include programs or groups having overlapping responsibilities, reward/accountability based on collective performance,29–33 mechanisms that make it easy to understand what each other is doing, and clear procedures that foster collaboration.29 Having shared perceptions and clear communication from leadership are also key to system change.34–36 While the general literature about collaboration is well established, little is known about programs that collaborate across age divides or across sectors, particularly when serving the needs of transition-age youth with serious mental health conditions. Understanding which types of programs collaborate more could help system reformers identify potential partners. Understanding malleable program factors (i.e., those that can be changed) associated with greater cross-age collaboration could also provide guidance for incentivizing or targeting system reform policies. The present study utilized social network analysis to examine program markers and malleable factors within programs that serve transition-age youth with serious mental health conditions as correlates of cross-age collaboration. Social network analysis has been used extensively in organizational studies as a way to understand collaboration and competition in coalition-building, alliance formation, and referral networks.27, 37–39 It describes which organizations are in a network or system, each organization’s characteristics, and the strength and direction of each organization’s relationship to other network organizations.37, 40 Social network analysis data collection methodology was established for mental health organizational systems by Morrissey and colleagues.37, 41 Details of applying this methodology to systems serving transition-age youth were published previously.18 Specifically, this study was designed to address three hypotheses about the association between cross-age collaboration rates and program markers and malleable characteristics that reflect previous findings on collaboration: 1. Programs’ demographic characteristics (markers) will be associated with different cross-age collaboration rates. Specifically, the following types of programs will have higher cross-age collaboration rates: programs serving only transition-age youth vs. programs serving only children or only adults; larger vs. smaller programs; younger vs. older programs; and more 358 The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 45:3 July 2018 vs. less specialized programs. The association of type of service provided (e.g., mental health vs. substance abuse) with cross-age collaboration was also explored. 2. Programs’ staff members’ perceptions regarding cross-age collaboration (malleable factors) will be associated with cross-age collaboration rates. Specifically, staff perceptions that crossage collaboration is achievable and that system level factors support or encourage cross-age collaboration (e.g., there are reward or accountability systems that encourage cross-age collaboration) will be associated with higher levels of cross-age collaboration. 3. Programs with higher levels of general within- or across-program mechanisms of collaboration will have higher rates of cross-age collaboration. Methods Recruitment In social network analysis methods, respondents are recruited because they have been identified as belonging to the network of interest.42 Two SAMHSA-funded Emerging Adult Initiative grantees43 and one Partnership for Youth Transition24 grantee served as research sites. One site was a medium-sized city of 600,000, and two were suburban metropolitan areas (populations of 345,000 and 240,000), each in a different state. Each site provided one knowledgeable community informant who was deeply familiar with services for transition-age youth in their community to identify programs in the network. To make the networks comparable in the three sites, criteria for inclusion and exclusion of programs were developed and applied across all sites. Priority was given to programs that directly provided mental health and related services to individuals with serious mental health conditions between the ages of 15 and 25 in the geographic area targeted in the grant activities. Programs could serve all or part of this age range. Because of the focus on cross-age collaboration, programs that served all ages were excluded. Knowledgeable community informants were provided a list of program types often found in child or adult service delivery networks for transition-age youth with serious mental health conditions (e.g., mental health, substance abuse, vocational and educational supports, independent living, or housing supports). Community informants were then asked to generate a list of the specific programs in the geographic area targeted by their SAMHSA grant that could serve individuals between ages 15 and 25 with serious mental health conditions. Named programs were sent an invitation letter and fact sheet via email and postal mail describing the study and asking them to designate a key informant from their program to participate in the study. The key informant for a program was described as an individual who occupied a boundary-spanning role that would make him/her knowledgeable about the practices within his/her program and the working relationships of his/her program with other community programs.40 Key informants were then invited to complete a one-time web survey and phone interview that assessed information about the program. A total of 87 programs were identified across the three grant locations. In grant location A, 26 eligible programs were identified and 20 key informants were successfully recruited to complete the phone interview and web survey (3 were non- responders after repeated attempts, 2 declined participation, and 1 program was de-funded during the recruitment period). In grant location B, 28 eligible programs were identified and 21 key informants were successfully recruited (2 were non-responders after repeated attempts, 3 declined participation, 1 required a lengthy IRB application that was not feasible, and 1 program was defunded during the recruitment period). In grant location C, 33 eligible programs were identified and 28 key informants were successfully recruited (3 were non-responders after repeated attempts, 2 declined participation). The overall response rate was 80%. The 20% Cross-Age Collaboration DAVIS ET AL. 359 missing response rate had a small to negligible effect on examining the overall network, as many of the missing agencies were peripheral to the network.44–46 Instruments and Measures The structured telephone interview consisted of three sections. Sections 1 and 2 were comprised of standard social network questions for mental health systems.37 To examine Hypothesis 1, Section 1 asked eight multiple choice questions about the program’s demographic information, the services it provided, and individuals served. Questions were added to standard social network analysis program characteristics questions that asked about the age groups served by the program (e.g., BPlease estimate the age composition of your program’s clients based on the unduplicated count above^). Section 2 was used to measure the main outcome variable of collaboration and included standard social network analysis system questions37, 41 which query about the interaction of the program with each program in the network in meeting for client planning purposes, meeting to discuss issues of mutual interest, sending referrals, receiving referrals, and sharing resources. Respondents answered these questions using a five-point Likerttype scale (ranging from 1, Not at All, to 5, Very Often). Section 3 asked respondents to endorse each specific service their program provided and then to endorse the age groups it was provided to (paralleling the age groups in the age question in Part I).18 The age group that each program served was identified from the questions in Part I and Part III regarding ages served. Based on these questions, programs were categorized into one of three groups of ages served: child only (under age 18 or 21), transition-age youth only (within the range of ages 15–25), or adult only (ages 18 and older). Analyses were limited to programs that clearly served one of these populations; seven programs in the study were identified as serving all ages and were removed from further analyses. The web survey included two measures (available from the authors). To examine Hypothesis 2, the first web survey measure was a constructed questionnaire about perceptions regarding collaboration challenges and leadership perceptions or attitudes about collaboration (specific items are listed in Table 3). Individual items were rated on a Likert scale of 1–6 (1 = Strongly Agree, 6 = Strongly Disagree) and the answers were collapsed to represent agreement (scores of 1–3) and disagreement (scores of 4–6). To examine Hypothesis 3, the second web survey measure was the Mechanisms of Collaboration Questionnaire (MoCQ), a constructed questionnaire assessing program practices that represent mechanisms for collaboration. These were asked about within-program practices (e.g., BJobs in my program have overlapping responsibilities^) and across-program practices (e.g., BWe share responsibility with other programs for the well-being of clients that we share^). Responses to both were rated on a Likert scale of 1–6 with lower scores indicating better collaboration. The MoCQ yields two scale scores: Collaboration Mechanisms within Programs (intra-program) has nine items and Collaboration Mechanisms across Programs (inter-program) has ten items. Analytic Approach While traditional social network analysis characterizes the whole network and its subgroups, the current research explores dyadic relationships (i.e., relationships between any two programs) across the networks in each of the three research sites. Specifically, this research explores cross-age dyadic relationships in which a program connects with another program that serves a different age (i.e., cross-age collaboration) across five activities of collaboration: sending referrals, receiving referrals, sharing resources, meeting for client planning purposes, and meeting for shared interests. In addition to establishing the extent to which cross-age collaboration exists, this study also explores 360 The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 45:3 July 2018 program characteristics and malleable factors that are correlated with cross-age collaboration. Because of this focus, the dependent variable is based on two constructs: the age category of the program (i.e., what ages the program serves) and the degree to which the program collaborates with programs that serve other ages. For social network analysis, each program’s relationship with each other program in their network was dichotomized into unconnected or connected for each of the five questions. Key informant responses of Don’t Know, Not at All, and Rarely were categorized as unconnected between programs while responses of Occasionally, Fairly Often, and Very Often were categorized as connected. Consistent with typical social network methodologies, responses to each question were included in a square matrix with binary data that indicated the presence or absence of a relationship (connected or unconnected) between any two agencies. A matrix was created for each question resulting in five matrices. Using UCINET 6.0,47 the five matrices were summed into one aggregate valued matrix indicating the strength, or weight, of the relationship. Homophily,48 a common measure in social network analysis, refers to the similarities in attributes or dimensions that exist among members of a network. In social network analysis, the homophily ratio is calculated by counting the number of a program’s connections with sameattribute programs (i.e., ages served) and dividing by the total number of the program’s connections. Thus, heterophily, the inverse of homophily, is the extent to which programs connected with programs serving a different age group. Percent heterophily is calculated by number of ties between an agency and another in a different attribute category divided by the agency’s total number of ties: H% ¼ E T where H% = percent heterophily, E = external connections (or cross-age attribute connections), T = total number of connections. For example, in the above formula, the number of connections a program that only serves children has with programs that serve transition-age youth only or adults only is represented by E. The total number of programs with which they have a connection is represented by T. For this analysis, the homophily algorithm in UCINET 6.0 for Windows47 was used to analyze the similarities of all outgoing relationships (i.e., relationship that a program reported they had with another program and not the reverse) for each program in the network regarding the ages served attribute. The inverse of that value (i.e., outgoing heterophily) was used to measure the level of cross-age (i.e.,, different ages served attribute) outgoing collaboration. In this sense, the heterophily measure could be used to identify cross-age collaborations, the extent to which organizations collaborate with agencies that serve different age groups from their own.25 A program’s heterophily score can range from 0 to 1 and is interpreted in this study as the percent of all of the outgoing connections in a network that are with cross-age programs. For example, a heterophily score of 0.6 indicates that 60% of all connections that program has to other programs are with programs that serve a different age group than it does. Analysis of variance was used to examine predictor variable group differences in heterophily scores (Hypotheses 1 and 2), and Pearson r was used to examine the relationship between continuous predictor variables and heterophily scores (Hypothesis 3). All three grant locations had programs in each of the three ages served categories. However, since programs serving transition-age youth only are a relatively new phenomenon18, they may not exist in most communities. In order to understand cross-age collaboration in more traditional child only and adult only programs, analyses were conducted first with all programs and then by excluding the transition-age youth only programs. This analytical process allowed us to examine factors that were relevant to child only and adult only programs without the effect of transition-age youth only programs. Cross-Age Collaboration DAVIS ET AL. 361 Results Program Descriptions Table 1 presents frequencies for the characteristics of the 69 programs. Comparable proportions were child only and adult only, with a smaller proportion being transition-age youth only. As can be seen from Table 1, there was a wide dispersion of program sizes (i.e.,, number of clients served per year) and a wide variety of services were offered. Across all programs in all three locations, the mean heterophily score was the middle of possible scores (Mean = 0.49 ± 0.27 SD). The three communities were located in three different states, so while there was a weak effect of grant location on heterophily scores (p G .05), post hoc analyses revealed no significant differences between any two pairs of grant locations on variables of relevance to this study. For this reason, data were combined across all three locations for all remaining analyses. Programs’ Demographic Characteristics Will Be Associated with Different Cross-Age Collaboration Rates Heterophily scores were markedly different depending on the ages a program served. Transitionage youth only programs had significantly higher heterophily scores (X = 0.69 ± 0.18 SD) than either child only (X = 0.44 ± 0.21 SD) or adult only programs (X = 0.42 ± 0.32 SD; F (2, 66) = 6.22, p G .005). These heterophily scores demonstrate the high proportion (69%) of connections that transition-age youth only programs have with programs serving other age groups, whereas fewer than half of the programs that child only and adult only programs connected with served other age groups. When transition-age youth only programs were removed from the analysis, mean heterophily scores dropped (X = 0.28 ± 0.24 SD) and heterophily scores were not significantly different between child only (X = 0.26 ± 0.20 SD) and adult only programs (X = 0.31 ± 0.29 SD; t(df = 49) = 0.65, p 9 .10). Thus, something in the nature of programs serving only transition-age youth contributes to high levels of collaboration with programs serving other age groups. Table 1 Participating program characteristics Variable Ages served (N = 69) Child only (G 18) Transition-age only (primarily 16–25) Adult only (primarily 18 and older) Years providing services (N = 65) 0 to 10 years 11 to 19 years Over 20 years Number of clients served in FY 2012 (N = 64) Less than 50 clients 51 to 199 clients 200 to 1000 clients Over 1000 clients 362 n (%) Variable n (% Yes) 28 (41%) 15 (22%) Services provided Mental health service Housing service 34 (50%) 22 (32%) 26 (38%) 28 (42%) 21 (31%) 19 (27%) 11 22 18 13 Independent living service Vocational service Substance abuse services Education services Recreation services Delinquency rehabilitation services 20 (29%) 18 (27%) 18 (27%) 15 (22%) 12 (18%) 9 (13%) (18%) (33%) (29%) (20%) The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 45:3 July 2018 Other program demographic characteristics were also examined including program size (number of clients served per year), program tenure, types of services provided, and specialization. As can be seen from Table 2, programs that served less than 50 clients and those who served over 1000 clients annually had the highest mean heterophily scores (F (3, 65) = 3.5, p G .05). This effect remained even when transition-age youth only programs were removed from the analysis (F (3, 52) = 2.7, p G .06), programs with over 1000 clients still had high heterophily (i.e., ≥ .50). This suggests that the high scores in small programs were primarily due to overrepresentation of transition-age youth only programs within small programs. Heterophily scores were not significantly different between programs that had existed for different tenures with or without the inclusion of transition-age youth only programs (F (2, 66) = 1.7, p 9 .10; F (2, 51) = 0.8, p 9 .10, respectively). With the exception of substance abuse services, there were no statistically significant differences in heterophily scores between programs that offered different types of services (see Table 2). Those programs that offered substance abuse services had lower heterophily scores than those that did not offer substance abuse services (p G .05). When transition-age youth only programs were removed from the analyses, there were no significant effects of service type on heterophily scores. Program specialization, defined as the number of different types of services offered (e.g., MH services plus vocational services = 2 types), did not significantly affect Table 2 Mean heterophily scores by program demographic characteristics Variable Program size* Less than 50 clients 51 to 199 clients 200–1000 clients Over 1000 clients Program tenure 0 to 10 years 11 to 20 years over 20 years Program specialization 1 service type 2 service types 3 service types Services provided Mental health Housing Independent living Vocational Substance abuse Education Recreation Juvenile justice All programs Child only and adult only programs X ± SD (n = ) X ± SD (n = ) .58 ± .28 .39 ± .20 .48 ± .28 .63 ± .19 .27 ± .22 .25 ± .20 .32 ± .29 .50 ± .25 (12) (22) (19) (13) (7) (21) (15) (10) .52 ± .27 (28) .42 ± .22 (21) .57 ± .23 (18) .35 ± .28 (19) .26 ± .19 (20) .34 ± .30 (13) .47 ± .26 (28) .50 ± .21 (11) .61 ± .24 (15) Yes (n=) .53 ± .26 (34) .55 ± .22 (22) .55 ± .27 (20) .41 ± .28 (18) .38 ± .27 (18)* .56 ± .33 (15) .44 ± .29 (12) .46 ± .23 (9) .30 ± .28 (22) .29 ± .18 (9) .43 ± .28 (11) Yes (n=) .33 ± .26 (28) .33 ± .27 (15) .24 ± .24 (13) .22 ± .21(14) .25 ± .27 (17) .35 ± .37 (9) .24 ± .20 (9) .26 ± .25 (8) No (n=) .47 ± .24 .48 ± .26 .48 ± .24 .53 ± .23 .54 ± .23 .48 ± .22 .51 ± .24 .51 ± .26 (34) (46) (48) (50) (50) (53) (56) (59) No (n=) .29 ± .25 .30 ± .25 .33 ± .26 .34 ± .26 .34 ± .25 .30 ± .23 .32 ± .26 .32 ± .26 (25) (38) (40) (39) (36) (44) (44) (45) *p G .05 Cross-Age Collaboration DAVIS ET AL. 363 heterophily scores with or without transition-age youth only programs (F (3, 67) = 1.3, p 9 .10; F (3, 52) = 1.3, p 9 .10, respectively, Table 2). Programs’ Staff Members’ Perceptions Regarding Cross-Age Collaboration Will Be Associated with Cross-Age Collaboration Rates Table 3 presents the mean heterophily scores for those who agree versus disagree with statements about collaboration between child and adult mental health. There were no significant agree/disagree differences in mean heterophily scores on these six items when all programs were included in the analysis. When transition-age youth only programs were excluded from analyses, one statement (BMy program funders want to see more collaboration^) was significant. Those who agreed with this statement had higher mean heterophily scores than those who disagreed with the statement. The proportion of programs that agreed with each statement were quite similar whether transition-age youth only programs were included or not. Programs with Higher Levels of General Within- or Across-Program Mechanisms of Collaboration Will Have Higher Rates of Cross-Age Collaboration Scores for the intra-program and inter-program subscales of the MoCQ were not significantly correlated with program heterophily scores ((N = 67), Pearson r = .09, p 9 .10; Pearson r = − .06, p 9 .10, respectively). Removing transition-age youth only programs from the analyses did not change these findings ((N = 53), Pearson r = − .02, p 9 .10, Pearson r = − .07, p 9 .10, respectively). Discussion The purpose of this study was to explore program characteristics and malleable program factors associated with variability in cross-age collaboration levels within networks of services that transition-age youth access. Of special interest was the extent to which programs serving only children and programs serving only adults were engaging in cross-age collaboration. Our findings regarding programs’ demographics, perceptions, and collaboration mechanisms revealed one strong finding: compared to child only and adult only programs, programs that serve transition-age youth only engaged in high levels of cross-age collaboration. The high level of cross-age collaboration exhibited by programs that serve transition-age youth only may be due to several factors. First, transition-age youth only programs may function as specialized programs in their networks (i.e., serving a small population defined narrowly). Previous literature on collaboration suggests that specialized organizations tend to be more limited in resources and will refer clients to bigger and more generalized organizations as a way to best benefit their clients.25, 26 Thus, the limited service capacity of transition-age youth only programs may promote their collaboration with child only or adult only programs because those programs have services or service capacity (e.g., openings in their services) that transition-age youth need. In addition, these programs’ Bmiddle^ position, in terms of ages served, would also make cross-age collaboration more likely. Child only programs would likely refer aging-out youth to these programs, and these programs would likely refer those that age-out of their services to adult programs. These referrals and activities associated with referral (such as meeting for client planning purposes) likely lead to forging some relationships with both child only and adult only programs. While the exact cause of the high heterophily scores among transition-age youth only programs cannot be determined by the current study, it is clear that this group of programs is likely to have developed skills for cross-age collaboration that are valuable to the system as a whole in enhancing better collaboration between child only and adult only programs. 364 The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 45:3 July 2018 Cross-Age Collaboration DAVIS ET AL. 365 *p G .05 There are significant barriers to coordinating across child/adolescent and adult services in the system. Think about 10 programs most important to your program. Leadership from those 10 programs, as a group, wants to see my program coordinate better across child/adolescent and adult services on behalf of transition-age youth and young adults. Our funders want to see the programs they fund coordinate more between child/adolescent and adult services on behalf of transition-age youth and young adults. System leadership has developed ways for child/adolescent and adult services to share responsibility for transition-age youth and young adults. System leadership has set up accountability mechanisms that require both child/adolescents and adult program coordination in order to achieve the targets. System leadership rewards programs that have coordinated well across child/adolescent and adult systems. Statement Table 3 .51 ± .25 .52 ± .24 .50 ± .22 .56 ± .17 .48 ± .20 76 58 45 36 .51 ± .26 Agree 84 84 % agree X ± SD All programs .51 ± .28 .46 ± .30 .50 ± .29 .45 ± .29 .46 ± .26 .47 ± .22 Disagree 43 38 − .4 (65) 58 − .1 (65) 1.6 (65) 77 83 85 % agree 0.9 (65) 0.6 (65) 0.4 (65) t (df) X ± SD .32 ± .19 .38 ± .16 .33 ± .23 .35 ± .24 .33 ± .25 .32 ± .26 Agree .32 ± .28 .27 ± .3 .30 ± .28 .19 ± .24 .24 ± .26 .29 ± .17 Disagree − .02 (51) 1.5 (51) 0.4 (51) 2.0 (51)* 1.1 (51) 0.4 (51) t (df) Child only and adult only programs Mean heterophily scores by agreement with statements about collaboration between adult only and child only programs This research identified only one malleable program factor that was positively associated with cross-age collaboration: the perception that funders wanted more cross-age collaboration among the programs they fund. Among child only and adult only programs, this finding suggests that funders could enhance cross-age collaboration through this mechanism. Given that none of the other malleable factors were significantly correlated with heterophily scores, this mechanism is a starting point for system reformers while other reliable mechanisms are yet to be discovered. System reformers, thus, have two mechanisms that these findings suggest may enhance cross-age collaboration: establish transition-age youth only programs and ensure that the child only and adult only programs perceive that their program funders want to see more cross-age collaboration. The only program marker of cross-age collaboration among child only and adult only programs was the finding that substance abuse treatment providers were less likely to engage in cross-age collaboration than those programs not providing substance abuse treatment. It may be that this type of service has more concrete program requirements or higher levels of governmental regulation that interferes with the flexibility that may be required to engage in cross-age collaboration. If substance abuse treatment providers are to be integrated into the network of programs serving transition-age youth, gaining a better understanding of the barriers to their cross-age collaboration would be valuable. Limitations Generally, the number of programs in networks of services that transition-age youth can access is small, as was reflected in the size of the networks the current program participants were recruited from. When categorized by the ages served by the program, the number of programs in each category became even smaller. While the sample size for this study was underpowered to detect weak effects, the 20% missing response rate had a small to negligible effect on examining the overall network, as many of the missing agencies were peripheral to the network.44–46 A second limitation comes from the lack of prior research into relationships among programs that serve transition-age youth. To date, there has been no metric established to measure the level of cross-age collaboration that exists within a service system. The work presented here is one of the first efforts to use data generated by social network analysis to measure this construct. One of the challenges in this new research area is that there is no commonly accepted way of measuring cross-age collaboration that can be used for validation. Without a separate Bgold standard^ that establishes what a Bgood^ or Bweak^ heterophily score is, researchers are dependent on face validity of the measure to prove its worth and are limited to simply describing higher or lower levels without any guidelines about concerning or strong levels. Heterophily, as an index, makes sense as a good measure of cross-age collaboration but whether it will become useful in making decisions about programs depends on validating it further, establishing guidelines for its valence, and understanding how programs with strong and weak heterophily function in networks. Because few of the variables demonstrated a significant relationship to heterophily scores, the causes of higher or lower heterophily are still unexplained. While these findings demonstrated higher levels of heterophily in transition-age youth only programs, the study does not elucidate why these programs had high heterophily scores, leaving this question to future research. Implications for Behavioral Health As the motivation to and knowledge about how to better serve transition-age youth with mental health conditions has grown, so too has the awareness of difficulties erected by the age divide between child and adult services. One way to help remedy those barriers is by better linking programs that serve these different age groups. Collaborations among programs foster innovation and the exchange of knowledge about the other services, as well as improving services for transition-aged youth. Thus, the 366 The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 45:3 July 2018 ability to measure cross-age collaboration accurately and the ability to increase cross-age collaboration in some programs are critical factors in the planning and administration of mental health services for this population. Programs that serve transition-age youth may naturally be inclined to collaborate across the age barrier because it is clear that their clients need the services and supports available in the adult or child system. However, planners and administrators need strategies to encourage programs that serve children only or adults only to collaborate across the age divide. To encourage cross-age collaboration in these programs, managers may need to create external incentives or pressures. The present findings suggest that one such incentive is for funders to clearly communicate the expectation for cross-age collaboration. This could be achieved through mechanisms such as contract language or RFA criteria that require cross-age collaboration. Other approaches might include financial incentives, access to special consultation or training resources, or special recognition within the service delivery system. Finally, research that explores additional program factors that can be modified is needed in order to understand how to increase cross-age collaboration. For example, staff training that focuses specifically on services within the adult mental health system and how to access these services might increase crossage collaboration from both the child only and transition-age youth only programs. The research reported here represents a beginning step toward measuring cross-age collaboration and thinking about programmatic interventions that will support better services for transition-age youth. Acknowledgements This manuscript was developed under a grant with funding from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research and the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Grant H133B090018, to the first author, The Learning and Working During the Transition to Adulthood RRTC). We are grateful to John Coppola, Pnina Goldfarb, Bruce Kamradt, and DeDe Sieler for their help with this project and the programs and their respondents who participated in this research. The contents of this paper do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR or SAMHSA and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Compliance with Ethical Standards Conflict of Interest There are no conflicts of interest to report. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A. 10-Year Research Update Review: The Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders: I. Methods and Public Health Burden. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005; 44(10): 972–986. U.S. Government Accountability Office. Young adults with serious mental illness. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2008. U.S. Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population by single year of age and sex for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014. Available online at https://www.census.gov/popest/data/datasets.html. Accessed March 15, 2017. Vander Stoep A, Beresford SA, Weiss NS, et al. Community-based study of the transition to adulthood for adolescents with psychiatric disorder. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000; 152(4): 352–362. Armstrong KH, Dedrick RF, Greenbaum PE. Factors Associated with Community Adjustment of Young Adults with Serious Emotional Disturbance: A Longitudinal Analysis. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2003; 11(2): 66–76. Wagner M, Newman L, Cameto R, et al. Changes over time in the early postschool outcomes of youth with disabilities. A report of findings from the national longitudinal transition study (NLTS) and the national longitudinal transition study-2 (NLTS2). Menlo Park, CA: SRI International, 2005. Cross-Age Collaboration DAVIS ET AL. 367 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 368 Wagner M, Newman L. Longitudinal transition outcomes of youth with emotional disturbances. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2012; 35(3): 199–208. Hartley, MT. Increasing resilience: Strategies for reducing dropout rates for college students with psychiatric disabilities. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2010; 13(4): 295–315. Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, et al.. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: Educational attainment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995; 152(7): 1026–1032. Davis M, Delman J, Duperoy T. Employment and careers in young adults with psychiatric disabilities. Worcester, MA: University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Psychiatry, Center for Mental Health Services Research, Transitions RTC; 2013. Fernandes-Alcantara AL. Runaway and homeless youth: Demographics and programs. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2013. Cauce AM, Paradise M, Ginzler JA, et al. The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents age and gender differences. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2000; 8(4): 230–239. Davis M, Banks S, Fisher W, et al. Arrests of adolescent clients of a public mental health system during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Psychiatric Services. 2007; 58:1454–1460. Sheidow AJ, McCart M, Zajac K, et al. Prevalence and impact of substance use among emerging adults with serious mental health conditions. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2012; 35(3): 235–243. National Conference of State Legislatures. Extending Foster Care Beyond 18. Available online at http://www.ncsl.org/research/humanservices/extending-foster-care-to-18.aspx. Accessed March 15, 2017. Davis M, Koroloff N. The great divide: How mental health policy fails young adults. In: Fisher WH, ed. Community Based Mental health Services for Children and Adolescents. Vol 14. Oxford, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2006: 53–74. Davis M, Hunt B. State adult mental health systems’ efforts to address the needs of young adults in transition to adulthood. Rockville, MD: U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2005. Davis M, Koroloff N, Johnsen M. Social network analysis of child and adult interorganizational connections. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2012; 35(3): 265–272. Friesen BJ, Koroloff N, Walker J, et al. Family and Youth Voice in Systems Care: The Evolution of Influence. Best Practices in Mental Health. 2011; 7(1): 1–25. Cox K, Baker D, Wong MA. Wraparound retrospective: Facotrs predicting positive outcomes. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2010; 18(1): 3–13. Holwerda A, Fokkens AS, Engbers C, et al. Collaboration between mental health and employment services to supportr employment of individuals with mental disorders. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2016; 38(13): 1250–1256. Swanson SJ, Courtney CT, Meyer RH, et al. Strategies for integrated employment and mental health services. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2014; 37(2): 86–89. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. BNow is the Time^ Healthy Transitions (HT): Improving Life Trajectories for Youth and Young Adults with, or at Risk for, Serious Mental Health Conditions: Request for Applications. Available online at https:// www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/grants/pdf/sm-14-017_0.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017. Haber MG, Karpur A, Deschênes N, et al. Predicting improvement of transitioning young people in the partnerships for youth transition initiative: Findings from a multisite demonstration. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2008; 35(4): 488–513. Wholey DR, Huonker JW. Effects of generalism and niche overlap on network linkages among youth service agencies. Academy of Management Journal. 1993; 36(2): 349–371. Provan KG, Sebastian JG. Networks within Networks: Service Link Overlap, Organizational Cliques, and Network Effectiveness. The Academy of Management Journal. 1998; 41(4): 453–463. Valente TW, Coronges KA, Stevens GD, et al. Collaboration and competition in a children's health initiative coalition: A network analysis. Evaluation and program planning. 2008; 31(4): 392–402. Bunger AC. Administrative Coordination in Non-Profit Human Service Delivery Networks: The Role of Competition and Trust. Nonprofit Volunteer Sector Quality. 2013; 42(6): 1155–1175. Majchrzak A, Wang Q. Breaking the functional mind-set in process organizations. Harvard Business Review. 1996; 5:93–99. White CM, Conway AM, Schoettker PJ, et al. Utilizing improvement science methods to improve physician compliance with proper hand hygiene. Pediatrics. 2012; 129: 1042–1050. Uchida M, Stone PW, Conway LJ, et al. Exploring infection prevention: Policy implications from a qualitative study. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice. 2011; 12: 82–89. Cook-Sather A. From traditional accountability to shared responsibility: The benefits and challenges of student consultants gathering midcourse feedback in college classrooms. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 2009; 34(2): 231–241. Vangen S, Huxham C. Nurturing collaborative relations: Building trust in interorganizational collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2003; 39(1): 5–31. Glisson C, Landsvert J, Schoenwalk S, et al. Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: Implications for research and practice. Administration & Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008; 35: 98–113. Kreger M, Brindis CD, Manuel DM, et al. Lessons learned in systems change initiatives: Benchmarks and indicators. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007; 39(3–4): 301–320. Salem DA, Foster-Fishman PG, Goodkind JR. The adoption of innovation in collective action organizations. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002; 30(5): 681–710. Morrissey JP, Calloway M, Bartko WT, et al. Local mental health authorities and service system change: Evidence from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Program on Chronic Mental Illness. The Milbank quarterly. 1994 72:49–80. Nicaise P, Tulloch S, Dubois V, et al. Using social network analysis for assessing mental health and social services inter-organisational collaboration: Findings in deprived areas in Brussels and London. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013; 40(4): 331–339. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 45:3 July 2018 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. Milward HB, Provan KG, Fish A, et al. Governance and collaboration: An evolutionary study of two mental health networks. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2009: 20(1): i125-i141. Van de Ven AH, Ferry DL. Measuring and assessing organizations. New York: Wiley. 1980. Morrissey JP, Johnsen MC, Calloway MO. Methods for system-level evaluations of child mental health service networks. In: MH Epstein, K Kutash, A Duchnowski (Eds). Outcomes for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders and their families: Programs and evaluation best practices. Austin, TX: PRO-ED, 1998, pp. 297–327. Laumann EO, Marsden PV, Prensky D. The Boundary Specification Problem in Network Analysis. In: Freeman LC, White D, Romney AK, eds. Research methods in social network analysis. Fairfax, VA.: George Mason University Press, 1989: 18–34. Walker J, Koroloff N, Mehess S. Community and state systems change associated with the healthy transitions initative. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2015; 42(2): 254–271. Kossinets G. Effects of missing data in social networks. Social Networks. 2006; 28(3): 247–268. Borgatti SP. On the robustness of centrality measures under conditions of imperfect data. Social Networks. 2006; 28(2): 124–136. Costenbader E, Valente TW. The stability of centrality measures when networks are sampled. Social Networks. 2003; 25(4): 283–307. Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC. Ucinet 6 for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies; 2002. McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review Of Sociology. 2001 27: 415–444. Cross-Age Collaboration DAVIS ET AL. 369