- No category

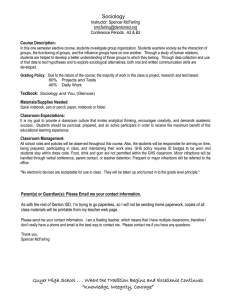

Herbert Spencer's Sociology: Theories & Moral Philosophy

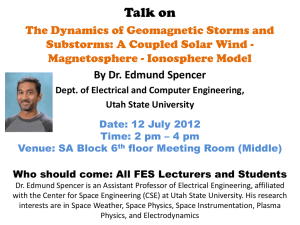

advertisement