Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Business Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jbusres

The impact of brand penetration and awareness on luxury brand desirability:

A cross country analysis of the relevance of the rarity principle

T

Jean-Noël Kapferera,⁎, Pierre Valette-Florenceb,c

a

b

c

INSEEC, 43 Quai de Grenelle, 75015, Paris, France

Grenoble IAE, Université Grenoble Alpes, BP 47, 38040, Grenoble, France

CERGAM, EA 4225, Aix-Marseille Université, France

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Keywords:

Luxury

Dream

Rarity

Penetration

Awareness

Negative-binomial regression

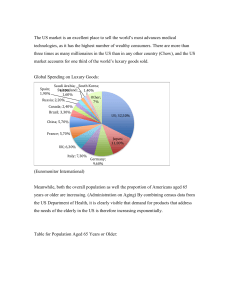

The global market for luxury brands has witnessed sustained growth in the last two decades, driven by purchases

from emerging economies such as China and rising upper middle classes. Because luxury is associated with rarity

and exclusivity, fears arise about whether continued growth might dilute the leading luxury brands' desirability.

Prior studies offer conflicting results about the effect of greater market penetration on luxury brands' desirability;

it appeared negative in the USA but not in Asia, today's highest growth luxury markets. The present research

analyzes 3200 luxury consumers' perceptions of 60 major brands across six Eastern and Western countries, both

emerging and mature. The overall effect of increased market penetration on luxury desirability remains negative,

while the impact of awareness remains always positive. This confirmation of the rarity principle has notable

implications for marketing luxury brands that seek to sustain their dream value.

1. Introduction

Once a niche sector, accessible only to the wealthy, luxury has become a thriving market, aiming at a vastly enlarged clientele, encompassing the upper middle class. After the 2008 economic crisis, the

personal luxury market began to grow again, reaching a rate of 30%

between 2011 and 2016 (Bain & Co., 2017). Although mature countries

remain the most important luxury markets, because of their purchasing

power and the flow of incoming tourists, future growth is elsewhere, in

the fast-rising, emerging countries. For example, the Chinese domestic

market for personal luxury goods currently ranks third worldwide (at

17.9 billion €), just after Japan (22 billion €), but already having bypassed France (17.1 billion €) and Italy (17.3 billion €). The United

States remains the top market (82 billion €) (Bain & Co., 2017). These

figures only measure domestic sales, yet modern consumers also shop

elsewhere in the world. Bain and Co. (2017) estimates that Chinese

consumers represent 31% of all purchases of personal luxury goods in

the world (Japanese 10% and other Asians 10%), when considering

what they buy both domestically and abroad while traveling.

Luxury, once the ordinary of extraordinary people, has become the

extraordinary of ordinary people too. Thus, the luxury market is

changing, and it appears likely to continue doing so, with global shifts

across national borders. Existing, predominantly Western luxury

brands, therefore, must determine if their traditional luxury

⁎

management approaches still apply among Eastern consumers. One

major question for the managers of highly successful luxury brands is

defining how well and how far they can generalize the notion that

luxury brands' desirability rests on maintaining some form of rarity and

exclusivity, thus on controlling the growth of brand penetration.

Continued growth and rarity seem two opposed notions.

To date, the academic literature has mainly focused on

luxury measurement (Vigneron & Johnson, 1999; Wiedmann,

Hennigs, & Siebels, 2007; de Barnier, Falcy, & Valette-Florence, 2012;

Kapferer & Valette-Florence, 2016a, 2016b), on diverse reactions to

marketing-mix variables such as price (e.g. Kapferer & Laurent, 2016;

Parguel, Delecolle, & Valette-Florence, 2016) or on luxury brand commitment antecedents (e.g. Shukla, Banerjee, & Singh, 2016). However,

in their everyday life, brand managers are more concerned with the

performance of their brand: how to create growth yet maintain its

luxury status. They monitor the growth of brand awareness and the

overall penetration of their brands on the market seen as a whole and

are sensitive to how these two parameters interact with the desirability

for luxury brands. In a sense, this point of view corresponds to a

paradigmatic shift from the study of individuality to the analysis at an

aggregate level of the interplay of brands operating on the markets.

One single pioneering study, conducted more than twenty years ago

in the United States and replicated in France, concluded that greater

market penetration dilutes the desirability of luxury brands

Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: jnkapferer@inseec.com (J.-N. Kapferer), pvalette@grenoble-iae.fr (P. Valette-Florence).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.09.025

Received 4 May 2016; Received in revised form 14 September 2017; Accepted 14 September 2017

Available online 10 October 2017

0148-2963/ © 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

2. Theoretical development

(Dubois & Paternault, 1995), but this effect did not arise in two replication studies conducted in Singapore or Hong Kong, a disconfirmation which seems to limit the generalizability of the rarity

principle to western clients. Asian consumers would be not at all the

same from that respect? This is the research gap we address: theory and

management need to know if the rarity principle is tied to the western

culture (quite individualistic) and does not apply in Asia, or if it is a

global principle. A cross country replication of the US seminal study

was designed to provide an unambiguous answer. Consequently, our

research focus is exclusively located at an aggregate level, trying to

analyze what the interplay is between luxury brand awareness and

luxury brand penetration in order to keep fueling the dream for luxury

brands.

Compared to the pioneering American study of Dubois and

Paternault (1995), our contribution is hence threefold. First, it is a replication in the USA, twenty years after the original study: since then,

many American luxury brands have been growing fast (Coach, Michael

Kors, Tory Burch, Polo Ralph Lauren, etc.) and moulded public perceptions of luxury in this country. Secondly, we extend this research to

Asian countries as well as European ones and South America, including

mature countries as well as emerging countries, which are the great

challenge for the future of the luxury industry. Thirdly, it represents an

improvement as to the measurement procedures, the statistical models

and the respondents' sample selection. Our results do confirm the hypothesis of the universality of the rarity principle, also known as the

‘dream equation’. However, they go one step further by showing that if

the overall tendency remains the same whatever the country, subtle

differences occur according to the culture, economic development of

the corresponding countries and the maturity of the luxury market in

these countries. Yet, our research does not aim at investigating the

possible intervening processes, but aims in priority at assessing or not

the validity of the rarity principle across countries and cultures, among

luxury buyers.

From a conceptual standpoint, our contribution refers to three main

theoretical approaches. First, it mostly rests on Brock's commodity

theory on the psychological effects of scarcity. Secondly, it also rests on

cultural differences between the western culture and the Asian one (for

instance as far as the need for uniqueness is concerned). Thirdly, it

makes reference to bandwagon effect versus snob effect theory.

Bandwagon effects (when one's choice follows the choice of the many)

should be prevalent in countries where conformity is rewarded (such as

China) or in new markets, where the consumers have not enough

confidence in their own choice. Snob effects may appear in luxury

mature markets where new riches need to differentiate themselves and

adopt newer and lesser known brands with less penetration.

Our results point out that although the dream equation seems to

hold true whatever is the country, hence extending the seminal work of

Dubois and Paternault (1995) to other countries than the USA, cultural

differences exist between mature countries (France, Germany and

Japan) and emerging ones (Brazil and China). Moreover, complementary and innovative statistical analyses shed light on the existence of thresholds of brand awareness and penetration beyond which

the impact of awareness and of penetration are fully operating on the

desirability of the brand, its dream value. Ultimately, and with regards

to those thresholds, managerial illustrations are provided per countries

and per brands.

Below, we first provide an overview of the theoretical background

relied on as to the interplays between luxury growth, luxury desirability, and cultural differences and rarity. We then present our research objectives, the methodology and the different stages involved in

the subsequent analyses. The article then details the main theoretical as

well as managerial contributions and concludes with a discussion of

further research avenues that warrant attention.

In the following sections, we shall address the core points of luxury

growth, luxury brand desirability, the moderating role of cultural differences and the rarity principle.

2.1. The challenge of luxury growth

Despite ongoing discussions about its precise meaning, the general

concept of luxury is familiar and quite clear, even if one person's luxury

is not identical to another person's (Berry, 1994). It refers to high

quality, hedonistic products, often handmade, that express tradition or

heritage and are sold in selective environments, at a price far beyond

their functional utility, such that they are associated with taste, elegance and the elite (Vigneron & Johnson, 1999; Kapferer & Bastien,

2012). Luxury value consists of two elements: luxury for the self (selfreward, self-pampering, self-elevation) and luxury for others, which

stems from the emotional pleasure of flaunting prosperity. According to

self-congruency theory (Sirgy, 1982), luxury buyers can either buy

luxury brands for themselves in order to satisfy their private self or for

others to fulfill their social self. Hence, luxury brands serve signaling

functions (Sundie et al., 2011), such that the rarity or exclusivity of a

luxury product adheres to its buyers. This function is especially important in fast growing economies with a rising class of new rich who

seek to make strong statements about their own success (Han,

Nunes, & Dreze, 2010).

The challenge of luxury brands thus is to sustain the notion or

dream of privilege and exclusivity even as they diffuse and grow in

popularity. This is all the most important today as many luxury brands

can be called mega-brands: they dominate in terms of market share, of

retail distribution and brand awareness (Solca, Bertini, & Fan, 2013).

Unlike fast-moving consumer goods, which seek to extend their

penetration and grow their sales constantly (Sharp, 2010;

Romaniuk & Sharp, 2016), luxury diffusion should seek to remain limited, to maintain the sense of rarity. Yet, growing inherently means

selling to more people, increasing the penetration of the brand, whether

through more stores, more product lines, e-commerce sites, communication or more accessible prices. Thus, there is an inherent risk that

growth might dilute the desirability of the leading luxury brands, on the

basis of the following paradox: the higher the dream, the higher the

sales, but the higher the sales, the lower the dream.

2.2. Why more sales create less desirability

All definitions of luxury relate to some form of rarity and exclusivity. Historically, luxury products were reserved for the aristocracy, then later spread to the happy few or the rich who wished to

emulate them (Berry, 1994). Only recently has luxury growth relied on

extensions of sales to the upper-middle class. Despite this extension,

perceived rarity and exclusivity remain underlying factors of the luxury

concept. De Barnier et al. (2012) factor analyzed three widely used

luxury perception scales and note that they share one convergent dimension: elitism. Thus, luxury value is based on perceived rarity and

the feeling that not everyone can or should possess a specific luxury

product or brand.

Although the term “commodity” accordingly seems remote from

luxury concerns, Brock's (1968) commodity theory is pertinent because

it addresses the psychological effects of scarcity and asks: Why does

scarcity enhance the desirability of anything that can be possessed? For

Brock, the possession of scarce products creates value through feelings

of personal distinctiveness and uniqueness, because possessions are an

extension of the self (Belk, 1988). In addition, people might prefer not

to look like everyone else, as suggested by need for uniqueness theory

(Fromkin, 1970; Snyder & Fromkin, 1980). Lynn (1991) tests these assumptions and shows that the stronger the need for uniqueness, the

more scarcity enhances value, especially for products purchased mainly

39

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

2.4. The rarity principle: Previous empirical research on luxury brands

for their symbolism (e.g., luxuries). As a strong test of this effect, Berger

and Heath (2008) reveal “taste abandonment,” or a shift in preferences

due to the post hoc realization that the product no longer acts as a

viable signal of uniqueness. This effect occurs most readily when too

many others, or else “rejected others,” adopt the product, causing it to

lose its uniqueness and ability to symbolize a preferred status. Luxury

brand penetration –the percentage of people having bought it – should

negatively impact perceived brand rarity and exclusiveness. This negative impact is especially true for luxury brands. Yet, it could be argued that doubling the sales of Bentley's in China (1595 units in 2016)

would not really impact its rarity, measured in percentage of the total

number of cars sold in this giant country. But rarity is not to be understood as an absolute concept: luxury buyers do not measure themselves up to laymen, to the masses but up to their peers (Han et al.,

2010). If there are four Bentley's in front of the Peninsula Hotel Hong

Kong, this will not impact absolute rarity, nor the brand appeal among

the masses, or the lower middle class, but it could impact its perceived

rarity among the riches themselves (Solca et al., 2013). It means that

this brand could lose its distinctive power and its feelings of exclusivity

among the high end luxury buyers themselves, those who not only

contribute to the business of Bentley's but above all to its prestige!

Scarcity may stem from two sources: lack of supply or excess demand. Gierl and Huettl (2010, p. 230) explore how sources of scarcity

interact with consumption to increase or decrease perceived value and

note that, “If a product is used for conspicuous consumption, signals of

scarcity due to limited supply are advantageous compared to signals of

scarcity due to high demand.” Some luxury brands thus restrict their

diffusion to enhance their desirability: Rolls Royce produced no more

4011 cars in 2016, and Ferrari made 8014. Hermès starves the market

of high end leather bags: there is one-year waiting list for the iconic

Kelly or Birkin bags.

Three studies directly addressed the rarity principle and the associated risk of decreased desirability when luxury brands' penetration

grows. A pioneering one, conducted in the United States, concluded

that greater market penetration dilutes the desirability of luxury brands

(Dubois & Paternault, 1995). However, this effect did not arise in two

replication studies conducted in Singapore or Hong Kong, which seem

to limit its generalizability to Western clients (Wong & Zaichkowsky,

1999; Phau & Prendergast, 2000). The present research is a replication

of the American pioneering study, an extension to Asian, European and

South American countries and to both mature and emerging countries.

Finally, it is an improvement in methodology, especially that of the

consumer sample recruitment, and the width of the brand sample. It

fills a research gap: the rarity principle is often claimed to be internationally valid, but -so far- empirical evidence is contradictory. Is the

rarity principle a myth? It also answers a managerial demand: to develop global luxury brands managers need to assess the validity of their

own managerial practices across borders and cultures.

The first study to address this rarity principle (negative impact of

more penetration on luxury brands' desirability) also coined the term

“Dream Equation” (Dubois & Paternault, 1995). The luxury industry

often refers to its role as “selling dreams” (e.g., dream boats, dream

places, dream watches). Bernard Arnault (2001, p. 117), the CEO of

LVMH, the world's leading luxury group with more than 70 brands,

describes luxury products as “items that serve little purpose in the lives

of consumers except to fulfill dreams. And those dreams don't come

cheap.” A content analysis of perceptions of luxury among consumers

from six countries confirms that “dream” is a frequently used term to

define luxury brands' uniqueness (Godey et al., 2013). What is this

dream made of? Luxury brands do indeed sell more than sophisticated

products and experiences: their desirability is also tied to the quality

and exclusivity of life symbolically attached to these products as well as

the heritage and prestige of their brands, and of their most glamorous

clients.

Dubois and Paternault (1995) focus on two levers of luxury desirability, brand awareness and brand penetration. Of course, luxury desire cannot be simply reduced to these two levers, but conspicuous

consumption requires a recognizable brand logo, because without

awareness, the luxury brand cannot perform its necessary role of costly

signaling (Nelissen & Meijers, 2011). With a representative U.S. sample,

including 3000 male and female consumers aged 15 years and older,

Dubois and Paternault conducted individual interviews about 34 personal luxury brands. To measure awareness, they used a single, aided

name awareness item. Because luxury is structurally associated with

feelings of rarity and exclusivity, they also measured the level of penetration of the brand (i.e., the aggregate of individually declared

purchases over the past two years). With regard to the “dream,” they

used a lottery simulation, asking respondents to select the five brands

they would like best if given the chance to choose a beautiful present.

Dubois and Paternault adopted brands as the object of their study:

their analyses were conducted at an aggregate level. They did not

choose to analyze at the individual level for it would have measured

another effect: the impact of knowing a name and of owning a product

on its desirability. It is evident first that one cannot dream about a

brand one does not know if only by name. As to the effect of individual

purchase on desirability, it would have measured if possessing a luxury

item dilutes its desirability, its dream value: do you still dream about

Rolex when you possess one on your wrist? Instead, the present research focuses on the impact of penetration (how many others have

bought) on a luxury brand's desirability. They selected 34 luxury brands

from diverse product categories. This choice is based three reasons:

2.3. Cultural differences

The moderating role of need for uniqueness, as posited by Brock

(1968), has another implication: luxury brands are now international,

and the importance of the need for uniqueness likely varies across international cultures. Managers of global brands thus need to know if

they can generalize their existing knowledge about luxury buyers'

psychology to consumers in Asian or emerging countries (Shukla,

Singh, & Banerjee, 2015). As Liang and He (2012) show, in China the

need for conformity is higher than in Western countries, where individualism is more prominent. Similarly, Zhan and He (2012) explain

preferences for well-known brands among Chinese luxury consumers as

functional, in that these mega-brands grant Chinese consumers a sense

of security about quality and enable the buyers to increase their face, by

enhancing their reputation and social status. This would explain the

long-lasting commercial success of Louis Vuitton in China. These results

echo Yang's (1998) study of Taiwanese fashion buyers, who do not wish

to express individualistic autonomy, as their Western counterparts do,

but rather seek to conform to contemporary mainstream norms. However, in an analysis of East Asian luxury consumers, Le Monk, House,

Barnes, and Stephan (2012) show that a face-saving norm has a negative impact on buyers' desire for exclusivity in China, but a positive

influence in Japan. Therefore, researchers cannot refer broadly to

“Asia”, but instead must account for the unique features of different

nations: China and Japan may both be Asian countries, but the former is

still a developing country, whereas the latter is one of the most developed economies in the world. Although our research is designed to

assess or not the validity of the rarity principle across countries and

continents, and does not aim at investigating the possible intervening

processes, we do expect differences in the magnitude of effects of penetration on luxury brand desirability among real luxury buyers.

• Luxury today is brought by brands. People enter not a leather bag

store, but a Prada store or a Coach store.

• Luxury brands have extended their range to many product

40

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

•

3. Research objectives, hypotheses and methodology

categories, selling a life style, thus encouraging the clients to come

back to the store or to the site

The luxury market today is concentrating itself, with many family

companies joining luxury groups (LVMH, Kering, Richemont, EPI,

etc.). Thus LVMH, world N°1 luxury group holds more than 70

brands, across 10 categories: leather, fashion, jewels, watches, cosmetics, fragrances, wine, spirits, travel and hospitality. Implicit is

the belief that beyond product category differences, there is a unique and shared way to manage a luxury brand in order to maintain

its luxury status.

The main research objectives will be first presented, followed by the

proposal of our hypotheses. Then the pursued methodology will be

detailed.

3.1. Research objectives

According to the rarity principle, high market penetration – a proxy for

perceived exclusivity within one's own social environment – is negatively

correlated to luxury brands desirability. This principle has been repeated

over and over in texts on luxury brand management (Kapferer & Bastien,

2012), such that it has become essentially a mantra of luxury brands, most

of which are European in origin. Yet, stockholders also demand that luxury

brands continue to expand their penetration worldwide, especially in fast

growing economies (e.g., China, Brazil). According to the traditional

managerial mantra and predictions, continued growth in these new

countries will put luxury brands at risk: it will dilute their feelings of exclusivity, a fundamental basis of their pricing power. Yet, as the preceding

literature review indicates, Asian consumers might be less sensitive to

rarity claims, such that more penetration would not dilute their dream as

much as it does for their Western counterparts. This would explain the

success of luxury mega-brands in Asia (Rolex, Chanel, Prada, etc.). To

determine if these cultural differences are relevant and actual in real-world

settings, as well as to help luxury managers understand how generalizable

the rarity principle is globally, this widescale study was undertaken across

six countries, with the premise that the dream equation will hold whatever

the countries.

This research then replicates the paradigm of the pioneer American

study, as well as the two disconfirming Asian studies; it extends the

research to more countries, so as to encompass both emerging and

mature markets, both Asian and Western. Finally, it aims at improving

the dependent variable measurement, the sampling selection process

and the models of statistical analysis.

When they regressed the dream value of these 34 luxury brands on

measures of awareness and purchase, Dubois and Paternault found a

significant positive beta weight for the former and a significant negative

beta for the latter. Thus, the equation known as the “dream equation”,

relating brand desirability to two major performance indicators of

brands:

Dream = 0.58 Awareness – 0.59 Purchase – 8.6 (R2 = 0.78).

This “dream equation” confirmed that brand awareness creates

value. It establishes the capacity of the brand to be recognized. Most

important -holding brand awareness constant- a brand's dream value is

negatively affected by a higher level of brand penetration in the population. The brand loses its perceived exclusivity. Therefore, to build

the dream, the difference between the levels of brand awareness and

brand penetration is of paramount importance.

These results (i.e., negative impact of more penetration on desirability) have been replicated in France (Kapferer & Valette-Florence,

2016a), despite some methodological differences (more luxury brands

from more diverse sectors, use of a binary measure of the dream value

of the luxury brands, its desirability, simpler than the lottery simulation

of the seminal study: “Does this brand make you dream?”). In contrast,

two replications conducted in Asian nations produced conflicting results regarding the rarity principle (i.e., negative effect of more penetration). Specifically, Wong and Zaichkowsky (1999) replicated the

methodology of the U.S. study in Hong Kong: they confirmed that

awareness boosts a luxury brand's desirability but uncovered no negative effect of the aggregate purchase level on dream. The methodology

they used relied on a convenience sample (n = 70, 40 men and 30

women) of relatively young Hong Kong residents (61% between 18 and

34 years), recruited as they visited popular shopping malls. The only

criterion was that they had bought at least one product among the

luxury brands on a list in the past three years; the list featured only

personal luxury goods. The authors offer no specific explanation for the

contradictory results, but they might reflect greater pressures toward

conformity in Confucian cultures, where being unique is not as valued

as it is in more individualistic, Western societies (Wong & Ahuvia, 1998;

Shukla et al., 2015). Considering the importance of conformity in Asian

societies, high brand penetration may not have the same deleterious

effects among consumers: this might explain the local continuing success of luxury mega brands such as Vuitton or Gucci. Another explanation would be that the sample was made of lower middle class

people attending popular shopping malls (not luxury shopping malls).

Among these consumers, bandwagon effect prevails (Tsai, Yang, & Liu,

2013). Bandwagon effect refers to “the extent to which the demand for

a commodity is increased due to the fact that others are also consuming

the same commodity” (Leibenstein, 1950, p189). Snob effect is just the

opposite.

Another study, undertaken in Singapore by Phau and Prendergast

(2000) and using the same methodology as Dubois and Paternault

(1995), also failed to reproduce the original U.S. findings. Brand popularity (awareness) propelled the dream value of luxury brands, but

these authors found no significant negative effect of aggregated penetration on the dream, after partialling out the impact of brand awareness. These authors refer to the local high need for conformity, to explain why mega luxury brands (high awareness and penetration) do

actually reassure buyers.

3.2. Hypotheses

This study seeks to provide comparable, relevant results across six

major luxury markets to assess the international validity of the rarity

principle, through the dream equation. Accordingly, we formally propose two main hypotheses:

H1. Brand awareness positively affects the luxury brand dream (brand

desirability) whatever the country.

H2. Brand penetration negatively affects the luxury brand dream (brand

desirability) whatever the country, holding brand awareness constant.

This universality hypothesis is based on the dual function of luxury

consumption (Kapferer & Bastien, 2012): luxury for self (self-rewards

and pleasure) or luxury for others (brands being a marker of social

stratification and the costly signaling of exclusivity). For a strong test of

the universality of the rarity principle, we needed to select important

luxury markets (Bain & Co., 2017) that also offer a distinction between

emerging countries (China, Brazil) versus mature ones (USA, Japan,

Germany, France), all from different continents. Emerging luxury

markets showed -until now- higher growth rates than mature countries

but the latter have higher levels of luxury consumption per capita.

In this contrast, across countries, we anticipated differences in the

amount of negative influence exerted by high penetration on desirability. This could be due to a number of potential factors, first of all

cultural factors. Our review of need for uniqueness theory suggests that

Chinese luxury buyers should be less sensitive to the rarity principle

than Japanese consumers. Yet Chadha and Husband (2007) also note

the importance of luxury for the fast rising class of new riches among

Chinese consumers, compared with the rather bespoke vision of luxury

in Japan. Similarly, U.S. luxury buyers should be less sensitive to the

41

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

Within each country, respondents were randomly presented a set of

15 brands among the 60 and simply had to indicate if each brand made

them dream (or not), if they knew it more than only by name (or not),

and if they already had bought it (or not). Since this study selected real

luxury buyers, it was hypothesized that these respondents were

knowledgeable about the brands and could voice a clear cut opinion

about which of these brands were luxury brands and which were not. In

addition the choice for asking single questions was in line with Rossiter

(2016) who also advises to use single-item measures for the many

constructs in marketing that are of an abstract nature. Moreover, since

each respondent had to randomly evaluate each of 15 brands, relying

on usual rating scales would have been too time-consuming. Real

luxury consumers do not have much time for academic research: this

justifies the choice of single binary questions for each evaluated brands

instead of ratings on lengthy Likert scales. The same choice had already

been adopted by the former studies on the international relevance of

the rarity principle, examined above. Because of the number of missing

values per respondent due to the randomness of the data collection

procedure and in order to be fully in line with our main research objectives, the results were therefore averaged for each country, leading

to aggregated data in which the 60 brands represented the observations

and using the mean averages of the variables as a percentage.

Contrary to the statistical methodology of former tests of the rarity

principle, multiple regressions of the relationships between the dream

value and awareness and penetration were not relied on here for three

main reasons. First, multiple regressions are not suited to handle count

data since they produce estimates that fall outside the 0–100 range, a

situation which does not make concrete sense. Second, they ideally

require a multivariate distribution which is very unlikely to hold in our

case. Third, parameter estimates rely on the restrictive assumption of

homoscedasticity which is rarely met in practice. Hence, we decided to

rely on specialized models more suited for analyzing count data which

avoid the aforementioned problems.

Since, in our case, the conditional variance exceeds the conditional

mean, a very restrictive assumption of Poisson regressions, we chose to

perform more general and powerful binomial-negative regressions.

Negative binomial regression is similar to regular multiple regression

except that the dependent variable is an observed count that follows the

negative binomial distribution. Based on the Poisson-gamma mixture

distribution, negative binomial regression loosens the restrictive assumption that the conditional variance is equal to the conditional mean

made by the Poisson model.

In practice, the regression equations are very similar to those of

multiple regression, except that we model the log of the response

variable. The dispersion parameter in negative binomial regression does

not affect the expected counts, but it does affect the estimated variance

of the expected counts. The coefficients have an additive effect in the

log (dream) scale and a multiplicative effect in the dream scale.

Although the beta coefficients give the sign value of the incidence of the

predictors' variables, the exponential form is often preferred as it can

explain directly the relative increase or decrease in the dependent

variable. For instance, a positive β1 value of 0.215 for awareness means

that increasing by 1% awareness would lead to an increase by 0.215%

in the logs of expected counts of the dream value of the brand, while

holding the other variables in the model constant. Looking at the exponential value term, this implies in a more explicit manner that increasing awareness by one unit will induce an increase of exp. (0.215)

= 1.240 or 24% in the dream value of the brand, while holding the

other variables in the model constant.

All analyses were in addition based on Bootstrapped estimates

(5000 replications). Furthermore, we also performed systematic power

analyses. Power represents the probability of rejecting a false null hypothesis, and is equal to one minus beta, beta being the probability of a

type-II error, which occurs when a false null hypothesis is not rejected.

Ideally, values greater than 0.90 are expected for power. In our case,

results proved to be satisfactory with values for power ranging from

snob effect (Leibenstein, 1950), also known as negative externalities

(produced by high brand penetration), than their European counterparts, but for different reasons. That is, the United States produces

worldly, successful luxury brands (e.g., Coach, Michael Kors, Marc Jacobs, Calvin Klein, and Ralph Lauren) that are positioned at lower price

points than their European counterparts and often distributed in offprice outlets in an effort to extend their penetration (Solca,

Grippo, & Lucarelli, 2017). This strategy may reflect the roots of U.S.

culture and the American dream of a classless society, in which access

to material happiness ideally is open to everyone. In contrast, French

luxury brands (e.g., Chanel, Dior, and Yves Saint Laurent) take very

high price positions and restrain their distribution network as an active

signaling of their rather elitist view of luxury. As our research does not

aim at investigating the possible intervening processes but assess (or

not) the cross country validity of the rarity principle, we propose the

following complementary hypothesis:

H3. Although always negative, the impact of penetration on desirability

varies by country. For instance, it should be lower in open societies,

claiming to be classless such as the USA and higher in highly elitist

countries such as France.

3.3. Sampling, brands selection and measurement

For a strong test of the universality of the rarity principle, the

sample interviewed across all countries should be both relevant and

consistent. The selection of the samples of luxury buyers in each

country thus relied on Internet panels, determined on the basis of respondents' self-declared purchases of a list of hedonic products, at a

price above a threshold that would indicate luxury. These products

appealed to both genders (e.g., a bottle of Champagne or wine for at

least 100 Euros, shoes for men or women for at least 350 Euros, sunglasses for at least 350 Euros, jackets for men or women for at least 400

Euros). These prices reflected the median levels determined in an international study of luxury price thresholds (Kapferer & Laurent, 2016).

On the whole, 3217 luxury buyers took part in the present survey.

Through the use of quotas, each sample was representative of its

country's luxury buyers in terms of geographical localization (e.g., main

cities on the East and West U.S. coasts; major cities in France, Germany,

Japan, and Brazil; main regional districts in China). Hence, and contrary to most previous researches relying on ad hoc young respondents,

we decided to focus on respondents who had already bought luxury

products in the last months before the survey, in order to ensure that

these respondents were real consumers of luxury products, hence fully

aware of what the pursuit of luxury means. In addition, all our samples

comprise both men and women, are spread in terms of age and exhibit

rather high monthly net income. As such, we acknowledge that our

samples are not fully representative of all luxury products buyers (including for instance all those who buy only exceptionally), but rather

representative and prototypical of affluent clients in each country, susceptible to be really concerned by luxury consumption, thus knowledgeable about luxury and the luxury brands too.

Table 1 displays the sample characteristics in terms of size, age,

gender, and net income. On average, 90% of the respondents lived in

households of at least two people, and approximately one-third earned

more than 5000 Euros per month (3.4% earned more than 15,000 Euros

per month).

Sixty worldly known and internationally distributed luxury brands

were included, spanning a high diversity of luxury sectors and representing both products and services. These brands were drawn from

lists of the members of Comité Colbert in France, Fondazione Altagamma

in Italy, and their equivalents in the United Kingdom and Germany.

These professional national organizations collectively promote the luxury

brands of their own country, in their domestic market as well as abroad.

Several Swiss and U.S. luxury brands also were included. Appendix 1

presents the list of 60 brands used in each country's survey.

42

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

Table 1

Gender, age and net income characteristics per countries.

Size

Gender

Men

Women

Total

Age

18–24

25–34

35–44

45–54

55–75

Total

Net income per month

< 3000 Euros

3000–4999 Euros

5000–9999 Euros

10,000–14,999

Euros

> 15,000 Euros

Total

Country

Total

France

USA

China

Brazil

Germany

Japan

N

%

N

%

N

267

50,1%

266

49,9%

533

313

62,5%

188

37,5%

501

324

48,2%

348

51,8%

672

337

62,6%

201

37,4%

538

292

57,0%

220

43,0%

512

283

61,4%

178

38,6%

461

1816

56,5%

1401

43,5%

3217

N

%

N

%

N

%

N

%

N

%

N

74

13,9%

106

19,9%

117

22,0%

99

18,6%

137

25,7%

533

66

13,2%

145

28,9%

121

24,2%

99

19,8%

70

14,0%

501

86

12,8%

204

30,4%

188

28,0%

141

21,0%

53

7,9%

672

107

19,9%

196

36,4%

124

23,0%

80

14,9%

31

5,8%

538

91

17,8%

140

27,3%

127

24,8%

121

23,6%

33

6,4%

512

56

12,1%

179

38,8%

57

12,4%

80

17,4%

89

19,3%

461

480

14,9%

970

30,2%

734

22,8%

620

19,3%

413

12,8%

3217

N

%

N

%

N

%

N

%

N

%

N

203

38,1%

177

33,2%

88

16,5%

18

3,4%

16

3,0%

533

96

19,2%

142

36,1%

181

24,2%

59

11,8%

28

5,6%

501

206

30,6%

201

29,9%

162

24,1%

41

6,1%

15

2,2%

672

236

43,9%

160

29,7%

62

11,5%

18

3,3%

19

3,5%

538

117

22,9%

188

36,7%

144

28,1%

24

4,7%

13

2,5%

512

106

22,9%

169

36,6%

117

25,4%

32

6,9%

19

4,1%

461

964

29,9%

1037

32,2%

754

23,4%

192

5,9%

110

3,4%

3217

sometimes rather low in magnitude, all regression parameter estimates

are statistically significant, all confidence intervals not incorporating

zero. The rarity principle is indeed relevant worldwide.

0.87 up to 0.98. All analyses have been performed per country by

means of Maximum Likelihood (ML) Estimation relying mainly on the R

package1 and Stata 14. ML being subject to interpretation, standard R2

should be regarded with caution and hence are not reported. Hence, we

decided to assess prediction by computing R2 on a replication sample.

Due to the rather limited sample size (N = 60) per country, we opted

for a K-fold random cross validation procedure. Hence, performing

multiple random drawing (K = 1500) of 40 brands in order to estimate

the predicted values on the remaining 20 brands in each country enabled us to compute mean R2 estimates on the replication samples. In

addition, as stated above, while using count data regression, a directly

analogous R2 for multiple regressions is not available. However,

Cameron and Windmeijer (1996), and more recently Mbachu, Nduka,

and Nja (2012), suggest relying on the deviance R-squared, which will

be hence reported as a benchmark and another supplementary means

for assessing the overall predictive power, along with a likelihood ratio

chi-square test which provides a test of the overall model comparing

this model to a “null” model without any predictors.

4.1. Checking the validity of the results

Hence, with regard to our assessment of the universality of the relationship of brand awareness and brand penetration with the luxury

dream, the results in Table 2 suggest a remarkable and similar pattern

across all countries, whether mature or emerging, Eastern or Western.

These findings do confirm the research hypotheses, H1 and H2. All

countries (though the United States to a lesser extent than expected

compared to the original research published in 1995) indicate that

higher penetration rates negatively influence the brand dream power,

whereas higher awareness reinforces it. Thus, unlike the two former

studies run in Hong Kong and Singapore on convenience samples,

which had disconfirmed the validity of the rarity principle in Asia, our

study based on larger samples of real luxury buyers assess the international validity of the rarity principle. In addition, we notice that

globally, the inhibitor effect of penetration is always lower than the

catalyst effect of brand awareness.

These results are striking, especially because we did not include

small, poorly known brands in our final sample of 60 brands, nor did

the sample feature masstige brands (Silverstein & Fiske, 2005) who use

communication to create a halo of prestige while pursuing ‘growth

without end’ (Schaefer & Kuehlwein, 2015, p 203). Including these

types of brands would have accentuated the regression weights of both

independent variables: (a) unknown brands cannot spark dreams while

well known ones can (b) masstige brands being more accessible in

price, have a less selective distribution, and thus enjoy a higher penetration rate while sparking less luxury dream. In the present study the

rarity effect actually does affect all luxury brands, even the most iconic

ones.

4. Main results

Table 2 presents the results of all the negative binomial regressions

run for each country separately, along with their corresponding K-fold

random R2 and pseudo-R2. Moreover, all the likelihood ratio chi-square

tests indicate a significant improvement over a “null” model as a baseline. They confirm our hypotheses: despite cultural differences between

countries as well as maturity differences between markets the beta

weights attached to the independent variables of the dream equation

appear as predicted: positive impact of brand awareness on the luxury

brand's dream value and negative impact of brand penetration. Although

1

glm.nb {MASS}.

43

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

Table 2

Negative binomial regression parameter estimates per country.

France : Bootstrapped parameter estimates

R² K-Fold=28.55%; R²deviance=30.05%

Likelihood ratio Chi-square: 25.875;

(df=2; Sig=.000)

Intercept

Penetration

95 % Confidence interval

B

Std. error

Lower

15,397

,145

3,1046

,0288

Awareness

,215

,0358

Negative binomial

,1 0 1

,0246

21,482

Upper

9,313

,201

,088

,145

,285

,0 6 3

,1 6 3

Hypothesis test

Exp(B)

Wald ChiSquare

S i g.

24,597

,000

2,056E-07

95 % Confidence interval for

Exp(B)

L o we r

U p pe r

4,681E-10

9,029E-05

25,296

,000

,865

,818

,915

36,011

,000

1,240

1,156

1,330

USA: Bootstrapped parameter estimates

R² K-Fold = 16.36%; R²deviance = 17.13%

Likelihood ratio Chi-square: 14.360;

(df=2; Sig=.000)

Intercept

PENETRATION

95 % Confidence Interval

B

0,523

,071

Std. error

1,4249

,0157

AWARENESS

,083

,0163

Negative Binomial

, 05 1

,0 1 6 0

Hypothesis Test

Exp(B)

Lower

Upper

Wald ChiSquare

S i g.

3,316

2,270

0,135

,713

,086

,055

,063

,105

, 0 28

,0 9 4

5,926E-01

95 % Confidence Interval for

Exp(B)

L o we r

U p pe r

3,630E-02

9,676E+00

3,988

,046

,931

,918

,946

7,171

,007

1,086

1,065

1,111

China: Bootstrapped parameter estimates

R² K-Fold = 37.36%; R²deviance = 40.57%

Likelihood ratio Chi-square: 32.863;

(df=2; Sig=.000)

Intercept

Penetration

95 % Confidence Interval

B

1,644

,036

Std. error

0,2452

,0034

Awareness

,032

,0034

Negative binomial

,0 4 0

, 01 5 8

Hypothesis Test

Exp(B)

Lower

Upper

Wald ChiSquare

S i g.

1,163

2,124

44,944

,000

,052

,012

,012

,044

,0 1 8

, 0 87

5,175E+00

95 % Confidence Interval for

Exp(B)

L o w er

U p pe r

3,200E+00

8,368E+00

3,830

,050

,965

,949

,988

29,562

,000

1,033

1,012

1,045

Brazil: Bootstrapped parameter estimates

R² K-Fold = 45.92%; R²deviance = 47.09%

Likelihood ratio Chi-Square: 47.127;

(df=2; Sig=.000)

Intercept

Penetration

B

Std. error

1,524

0,2632

,045

,0019

Awareness

,047

,0033

Negative binomial

,0 1 5

, 0 09 2

95 % Confidence interval

Hypothesis Test

Lower

Upper

Wald ChiSquare

S ig .

1,008

2,040

33,523

,000

,054

,011

,030

,056

, 00 4

,0 5 0

Exp(B)

4,590E+00

95 % Confidence Interval for

Exp(B)

L o we r

U p p er

2,740E+00

7,689E+00

59,335

,000

,956

,948

,989

64,957

,000

1,049

1,030

1,057

Germany:Bootstrappedparameterestimates

R² K-Fold = 23.32%; R²deviance = 24.80%

Likelihood ratio Chi-Square: 18.672;

(df=2; Sig=.000)

Intercept

Penetration

95 % Confidence Interval

B

Std. error

Lower

6,938

,074

2,2693

,0228

Awareness

,113

,0263

Negative binomial

,0 6 6

,0198

11,385

Upper

2,490

,086

,054

,071

,139

, 03 7

,1 1 9

Hypothesis Test

Exp(B)

Wald ChiSquare

Si g.

9,346

,002

9,707E-04

95 % Confidence Interval for

Exp(B)

L ow e r

U p pe r

1,136E-05

8,292E-02

5,798

,016

,928

,918

,947

18,627

,000

1,120

1,074

1,149

Japan:Bootstrappedparameterestimates

R² K-Fold = 22.04%; R²deviance = 23.39%

Likelihood ratio Chi-square: 17.420;

(df=2; Sig=.000)

Intercept

Penetration

95 % Confidence interval

B

3,296

,069

Std. error

2,3749

,0175

Hypothesis test

Exp(B)

Lower

Upper

Wald ChiSquare

Si g.

7,950

1,359

1,926

,165

,085

,055

Awareness

,084

,0265

,070

,126

Negative binomial

, 01 4

, 0 0 87

, 00 3

,0 43

3,705E-02

95 % Confidence interval for

exp(B)

L o we r

U p pe r

3,526E-04

3,893E+00

2,896

,089

,933

,919

,946

7,850

,005

1,087

1,073

1,135

NB 1: Figures in bold type and framed in black refer to France only

NB 2: Figures in bold type and italics and framed in red refer to non different parameter estimates (Germany, Japan and US)

NB 3: Figures in italics and underlined and framed in blue refer to non different parameter estimates (Brazil and China).

Germany, the corresponding β is 0.275 inducing a R2 increase of 8%.

Not surprisingly, Germany which holds a long tradition of manufacturing high-end luxury cars has the highest impact of luxury cars on

dream, as luxury buyers are used to be in touch with, to possess and to

drive them more than in any other countries. Ultimately, we also did

the analysis without Ferrari and Rolls Royce which both enjoy having

the smallest penetration in each country, the highest brand awareness

level and also being held as the most “dreamable” cars in the world.

This did not change the results which remain remarkably the same

across all the countries. Hence, all the aforementioned methodological

precautions give full support to our interpretations.

Despite the similarities of the overall patterns though, some

Now it could be argued that the above results are spuriously created

by the presence of 12 luxury automobile brands within the sample of 60

luxury brands. These brands are by definition very expensive, thus have

little penetration and spark high dreams. To offset this remark, an

analysis holding cars as dummy variables was undertaken. This did not

change the results since the overall pattern of regressions coefficients

remains unchanged across the countries. More precisely, penetration

still negatively impacts the dream, while awareness still shows a positive incidence on the dream.

Being a luxury car always positively and significantly impacts the

dream, resulting in an increase of R2 ranging from 4 to 8% (full results

are available upon request, in order to preserve space). For instance, in

44

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

Table 3

Homogeneous subsets tests of negative binomial regression coefficients.

Penetration

Country

Homogeneous subsets α = 0.05

1

France

Germany

USA

Japan

Brazil

China

Sig.

2

3

-0.145

-0.074

-0.071

-0.069

1.000

0.648

- 0.045

- 0.036

0.181

2

3

Awareness

Country

Homogeneous subsets α = 0.05

1

China

Brazil

USA

Japan

Germany

France

Sig.

0.032

0.047

0.083

0.084

0.113

0.185

0.115

differences exist, as predicted by H3. To assess the differences across

countries, we relied on bias-corrected bootstrap difference tests (5000

replications) of regression coefficients across countries. Results strongly

support hypothesis H3, showing that the impact of penetration on desirability varies by country.

More precisely, we identified three groups based on the beta

weights measuring the impact of awareness and penetration on the

dream value of the brand:

•

•

• China and Brazil – the two emerging markets of our study- exhibit

very close beta weights (framed in blue, table 2);

• Germany, Japan and US form another group (framed in red, table 2).

These are both western and Asian countries, but mature markets;

• France stands alone (framed in black, table 2). In addition, Table 3

displays the corresponding homogeneous subsets tests.

There are also striking differences between countries (Tables 2 and 3):

• The negative effect of penetration on the dream value is strongest in

France. This is evidenced by the β2 value (measuring the impact of

penetration on the logarithm of dream, β2 = − 0.145). If one now

looks at the exponential value term (Exp β2 = 0.865), the result

indicates that holding awareness constant, one increase of one unit

in penetration would induce a decrease of 13.55% (1–0.865) in the

dream value of the brand. This negative impact is far above the one

of German clients (β2 = −0.74), Japanese clients (β2 = − 0.69) as

well as US clients (β2 = −0.71). This is probably reflecting France's

very elitist vision of luxury, as already identified by a research

comparing attitudes toward luxury between 20 countries (Dubois,

Laurent, & Czellar, 2005). Although competing against each other,

French luxury brands such as Dior, Chanel, Hermès or Louis Vuitton

collectively promote the same specific idea of what is luxury, based

on three pillars of highest product quality, being very expensive and

prestigious brands (Kapferer, 2015). France has never produced

“accessible luxury” brands. Here luxury brands should not sell to too

many people, otherwise they cannot claim to be luxury brands. This

is a paradox for a country whose 1789 Revolution promoted

•

45

0.215

1.000

equalitarianism. Yet many French luxury brands stress their legendary history, linked to France's former kings and emperor.

Looking at these four countries altogether (France, Germany, USA,

and Japan), luxury clients from these mature countries are all quite

sensitive to higher brand penetration, all negatively, meaning that

for them luxury growth needs to remain strictly under control, if the

brand wants to sustain its feelings of exclusivity which underpin

luxury desirability.

Chinese and Brazilian luxury buyers also are negatively sensitive to

the effect of penetration on the dream of luxury (respectively

β2 = − 0.045 and β2 = − 0.036). These two negative and significant beta weights reflect the conspicuous role of luxury consumption in Asia (Chadha & Husband, 2007) as well as in fast

moving emerging Latin American countries. Yet as indicated in

Table 3, luxury buyers from these two emerging countries are less

negatively sensitive to increased market penetration than their

counterparts from mature countries. As discussed in the theoretical

part of this article, in the Chinese culture the need for uniqueness is

less strong. In a country where conformity is still rewarded, bandwagon effects are operating (Kastanakis & Balabanis, 2012). As a

result brands have to reach higher levels of penetration to stimulate

the snob effect. In the case of Brazil, one cannot invoke conformity

pressures to explain the data. Rather the state of development of the

luxury market. At this time, despite the importance of its population, Brazil is not yet a strong luxury market (Bain & Co, 2017):

brands are still to be pushed if luxury consumption is to take off. It

may be too early to witness snob effects, leading clients to abandon

their luxury brands when their penetration is felt as excessive.

The positive effect of awareness is by far the strongest in France

(β1 = +0.215, impact on the logarithm of the brand dream value).

In other words, it means that holding penetration constant, one

increase of one unit in awareness would induce an increase of exp.

(0.215) = 1.240 or 24% in the dream. The French love demonstrations of power where everyone knows you but few can access.

Once again, German (β1 = + 0.113) and to a lower extent Japanese

(β1 = +0.084) as well as US (β1 = + 0.083) luxury buyers are also

sensitive to higher brand awareness.

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

Table 4

Penetration and awareness threshold points by country.

France: P* = 3 and

A** = 88

USA: P = 6 and

A = 91

Japan: P = 6 and

A = 92

Germany: P = 6 and

A = 92

Brazil: P = 29 and

A = 87

China: P = 33 and

A = 92

Brands below the threshold points

Brioni

Coach

Donna Karan

Ermenegildo Zegna

Grey Goose

Harry Winston

Mandarin

Marriott

Martell

Mikimoto

Patek Philippe

Peninsula

Tom Ford

N = 13

Brioni

Boucheron

Breitling

Christian Louboutin

Ermenegildo Zegna

Guerlain

Harry Winston

Mandarin

Martell

Maserati

Mauboussin

Mikimoto

Patek Philippe

Peninsula

Tod's

N = 15

Brands always

concerned by the dream

equation

Brands above the

threshold points

Brioni

Aston Martin

Boucheron

Donna Karan

Ermenegildo Zegna

Grey Goose

Guerlain

Hyatt

Mandarin

Marriott

Martell

Maserati

Mauboussin

Patek Philippe

Relais & Châteaux

Tod's

Tom Ford

N = 17

Brioni

Baccarat

Boucheron

Christian Louboutin

Coach

Donna Karan

Ermenegildo Zegna

Grey Goose

Guerlain

Harry Winston

Hyatt

Lexus

Mandarin

Marc Jacobs

Maserati

Mauboussin

Mikimoto

Patek Philippe

Peninsula

Relais & Châteaux

Tod's

Tom Ford

N = 22

Brioni

Baccarat

Boucheron

Breitling

Coach

Daslu

Donna Karan

Ermenegildo Zegna

Guerlain

Harry Winston

Hennessy

Hyatt

Mandarin

Marc Jacobs

Marriott

Martell

Maserati

Mauboussin

Mikimoto

Patek Philippe

Peninsula

Tod's

Tom Ford

N = 23

Brioni

Aston Martin

Baccarat

Boucheron

Breitling

Burberry

Cartier

Coach

Dolce & Gabbana

Dom Perignon

Donna Karan

Ermenegildo Zegna

Givenchy

Grey Goose

Harry Winston

Hyatt

Jaguar

Mandarin

Marc Jacobs

Marriott

Martell

Mauboussin

Mercedes

Mikimoto

Moet & Chandon

Montblanc

Patek Philippe

Peninsula

Prada

Qeelin

Ralph Lauren

Ritz Carlton

Shang Xia

Tiffany

Tod's

Tom Ford

Versace

Yves Saint Laurent

N = 38

Armani

Audi

BMW

Bulgari

Cadillac

Chanel

Dior

Ferrari

Gucci

Hermès

Lacoste

Louis Vuitton

Mercedes

Omega

Porsche

Rolex

Rolls Royce

Swarovski

N = 18

P* = Penetration threshold; A** = Awareness threshold; N = Number of brands below the threshold points.

Brands in bold type are always below the threshold points whatever are the countries, whereas those in bold italics are always above the threshold points.

Brands in italics (Qeelin and Shang Xia) are specific to China.

• Chinese and Brazilian luxury buyers are also sensitive to the positive

sample of 60 brands in each country. Now one might ask: above what

level of brand awareness AND of market penetration is the dream

equation significant, while for all brands below these awareness AND

penetration levels, i.e. below both thresholds, the dream equation

would not hold.

To answer, systematic heuristic searches give these points displayed

in Table 4, along with the corresponding brands below these points,

that is to say, not yet affected by the impact of either awareness or

penetration on the luxury brand dream value.

Globally, and supporting previous results, three main clusters of

countries emerge:

effect of brand awareness on the luxury dream (logarithm) (respectively β1 = 0.047 and β1 = 0.032). But in comparison with

their mature countries counterpart examined above, they are less

sensitive to this positive effect of awareness on the dream of luxury.

In the emerging countries, luxury diffusion is progressive: it is first

bought by a minority, but this minority who travels is quite

knowledgeable about the brands. As these consumers learn more

about different luxury brands, they evaluate the best-known brands

more negatively as uniqueness-seeking becomes a more important

goal. (Zhan & He, 2012).

• France still stands aside the other countries. The threshold point for

4.2. Threshold analyses: Diagnosing which brands are most concerned

penetration is the lowest among all countries (P = 3%), as well as the

threshold point for brand awareness (A = 88%), also smaller than the

other western developed countries. France holds a very long-lasting

relationship with luxury brands and promotes a quite aristocratic and

elitist vision of luxury (Dubois et al., 2005): as a result, luxury brands'

dream value is soon negatively impacted by penetration. As shown in

the first column of Table 4, the dream equation (in other words the

rarity principle) is impacting the great majority of the brands (47/60

Ultimately, and mirroring recent techniques performed in mediational analyses (Spiller, Fitzsimons, Lynch, & Mcclelland, 2013) relying

on the Jonson-Neyman point (1936), we performed a threshold analysis

with the aim of uncovering the threshold points related to the impact of

BOTH awareness and penetration on the luxury brand dream value.

How does this relate to former analyses examined above? The nonlinear

regressions - sources of Table 2- were estimated across the whole

46

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

•

•

our results confirm that the rarity principle is relevant to luxury buyers

across countries, Eastern and Western, emerging and mature. As expected from the theoretical discussion, a positive and significant effect

of awareness on the luxury brand's dream, as well as a negative effect of

penetration, emerged. The discrepancy with the two disconfirming

former Asian studies (run in Hong Kong and Singapore) can be explained by variations in the nature of their samples (small and convenience). When the sample consists of real luxury consumers, selected

on the basis of the same behavioral criteria (buying specific products

priced above a certain level) greater penetration leads to lower desirability. In all countries, luxury exists because not everybody can access

it.

Greater brand penetration causes the luxury brand to change its

status and suffer negative externalities, similar to those that result from

the presence of counterfeits (Grossman & Shapiro, 1988). The brand no

longer fully acts as a signal of distinction or the superiority of the

owner; instead, it becomes an integrative means for followers to mimic

the tastes of the rich (Han et al., 2010). When too many people buy a

luxury brand, the elites abandon those options and seek to recreate

their symbolic distance from followers (Amaldoss & Jain, 2005): this is

called the snob effect. Yet the happy many hope that luxury remains

accessible and are not bothered by its increased diffusion; the happy

few clearly do not share this vision.

Beyond this overall picture, we find some idiosyncrasies across

different countries. In contrast with Dubois and Paternault's (1995)

initial findings, we find a significant yet lower negative impact of penetration on the luxury dream in the U.S. sample. This discrepancy may

reflect the impact of the successful U.S. luxury brands which have been

launched since then: they compete through lower price points, e-commerce sales as well as extensive outlet networks. Doing so they promote

a more accessible vision of luxury, at least more accessible than the

vision of their European counterparts, where more penetration is less of

a problem than for instance in France, up to a tipping point where they

do lose distinctiveness (Solca et al., 2017). The other mature countries

follow the same rules quite similarly, which is remarkable since we also

included Japan. Finally, there is a homogeneous group made of emerging countries, Brazil and China behaving more in the same way

compared to the remaining mature countries. In these two countries the

luxury market is more recent. Consumers have to learn. Bandwagon

effects prevail over the snob effect: this is why -in these two countriespresent clients are only slightly negatively sensitive to luxury brands'

growing penetration rates.

or 78%). Very few luxury brands (13) are not yet subject to the

threats implied by the rarity principle. The latter brands should invest

in growing their dream: they still lack saliency (deficit of brand

awareness) and visibility (deficit of commercial presence and market

penetration). These brands are bespoke brands (at least in this

country), such as Brioni (expensive suits for men), E. Zegna, Patek

Philippe, Tom Ford, Mikimoto pearls, or D. Karan and The Peninsula

Hotel which opened only recently in Paris.

A second group comprises the three remaining developed countries

(USA, Germany, Japan), with almost identical threshold points for

awareness and penetration. For these countries the penetration

threshold point turns around 6% and the threshold of awareness

around 92%. Compared to France's extremely elitist vision, those

countries don't have such constraints. Consequently, penetration has

to be higher before it can damage the dream. Noticeably, the same

brands still need to boost their dream by means of more penetration

and more awareness (Brioni, Patek, Zegna).

Lastly, Brazil and China belong to a third group, characterized by

much higher thresholds of penetration (P ≥ 23%) along with a rather higher threshold of awareness (A ≥ 87%). Indeed, in these

developing countries, the luxury market is growing, step by step

(Chadha & Husband, 2007). It has not diffused too much below the

boundaries of the upper middle class: as a consequence, at an aggregate level, penetration –as measured within this sample of luxury

buyers – has to reach a higher level before damaging the dream. This

is why in China 38 brands among the 60 (63.3%) still need to grow

their penetration and awareness: the rarity principle does not impact them yet, they are perceived as too confidential to create enough value, enough luxury dream. The number of such brands is

also high in Brazil (23/60 or 38.3%).

Globally, across all countries, three brands are not creating enough

dream and are not subject to the impact either of awareness nor penetration. Brioni and Ermenegildo Zegna are still far too confidential

than the other brands encompassed within this research and hence are

not suffering any form of excessive penetration. The same reasoning

seems to apply for the high-end luxury manufacturer Patek Philippe.

These brands have hence still room to develop in all countries (except

Switzerland) whatever their dream level is.

On the contrary, across all six countries, there are eighteen luxury

brands on which bear the Damocles' sword, the rarity principle, implying a negative impact of penetration on the brand dream power,

holding awareness constant. These brands are Armani, Audi, BMW,

Bulgari, Cadillac, Chanel, Dior, Ferrari, Gucci, Hermès, Lacoste, Louis

Vuitton, Mercedes, Omega, Porsche, Rolex, Rolls Royce and Swarovski:

they stand always above the two thresholds. They are what Solca et al.

(2013) call the “luxury mega-brands” with high revenues, extended

penetration and visibility. The brand managers of these brands should

be aware of the risks and start at least stopping the retail expansion if

not downsizing the retail network.

The presence of Ferrari among the brand most concerned by the

dream equation could be a surprise. Isn't this brand starving the market

by limiting its production of automobiles? The answer is that only two

thirds of Ferrari operating profits are attributable to automobiles and

engines. A third is produced by media rights and also the multiplication

of licenses (Saviolo, 2011). All around the world, Ferrari megastores

sell licensed articles (apparel, belts, T shirts, eyewear, watches, toys,

mugs,...) to the masses: their proliferation could dilute the halo of exclusivity of the brand.

5.2. Implications for management: Shrink to grow?

This research confirms the paradox: The more desirable a luxury

brand is, the more it sells. The more it sells, the less desirable it becomes. As a luxury brand expands its sales, its dream value gets diluted

by greater penetration. A luxury brand cannot invoke dreams if it is too

unknown or if its brand penetration is too high. In operational terms,

these results confirm that managing a luxury brand requires sensitivity

to the different parameters fueling the dream value of a luxury brand.

The rarity principle has proven valid across the Eastern and Western

markets analyzed in this study. A luxury brand might confront various

situations that require different distribution and communication responses.

For example:

• Low brand awareness, below the threshold, in which case the luxury

brand cannot perform its signaling function. Regardless of the

quality or exceptionality of the product or service, the brand cannot

leverage the renown of its name as an essential marker of value

among consumers who are not buyers but who nevertheless might

recognize the brand displayed by a luxury owner. In this case, it is

time to invest in communication, going beyond the core target

market.

5. Conclusion and discussion

5.1. Theoretical contributions

Overall, our three hypotheses are confirmed. Rooted in both commodity theory (Brock, 1968) as well as need for differentiation theory,

47

Journal of Business Research 83 (2018) 38–50

J.-N. Kapferer, P. Valette-Florence

• As

•

•

•

•

2

most expensive lines. Chanel thus overinvests in advertising its most

expensive jewelry items. Finally, luxury brands growing through

accessible extensions should do so outside their core business while

also launching highly publicized, expensive, limited editions of their

core products. Hermès, to increase its market penetration and attract new consumers, sells silk shawls at 350 euros and silk ties at

150 euros. But it also strictly limits the volume of its iconic leather

bags (leather is Hermès's core business), charges very high prices for

them, and controls their retail presence tightly (Kapferer & ValetteFlorence, 2016a).

awareness increases, luxury brands should open new stores

progressively. There is no need to “burn the brand” through excess

communication, an ubiquitous Internet presence, or too many store

openings in the same city or district. The optimal number of shops is

specific to the product category: for fragrance brands, a frequent

purchase, consumers may want shops close enough to their home or

workplace, but this demand is less pertinent for men's luxury suits.

High penetration also results from an excess of accessible lines (licenses, accessories) or counterfeits. The essence of luxury is rarity,

which applies not only to the product but also to buyers. Selling to

many consumers disrupts the signaling function and price justification for luxury. Luxury brands therefore must regain their selectivity by reducing the number of shops, refraining from entering

China's Tier 3 cities, reinvesting in their core business, emphasizing

a premium strategy, and increasing the average price of their products. Then, they can attempt to reengage with cultural elites, such

as by cooperating with avant-garde artists or renowned designers to

endow the brand with a renewed image. They could also create a

secret private club for their best clients, allowing them access to

exceptional events organized for them by the brand.

If a brand becomes too diffused, it still can grow its sales and profits,

but the core luxury customers may leave, which limits the value of a

key asset of any luxury brand, namely, its clientele as a source of

prestige. In this situation, some brands may decide to shrink their

penetration in order to regain desirability. Others prefer to change

their business model, leave the luxury market, and grow their distribution further. For example, Mauboussin jeweler, a formerly