Creativity Research: Review of Traits, Influences, and Perspectives

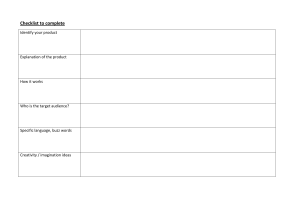

advertisement