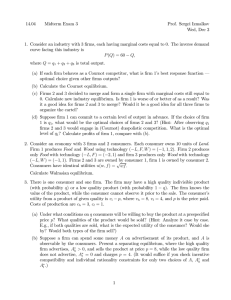

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/2040-8269.htm Corporate governance and failure risk: evidence from Estonian SME population Virgo Süsi and Oliver Lukason School of Economics and Business Administration, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia Failure risk 703 Received 6 March 2018 Revised 2 September 2018 Accepted 11 December 2018 Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this study is to find out how corporate governance is interconnected with failure risk in case of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Design/methodology/approach – The study is based on Estonian whole population of SMEs, in total 67,058 observations, and data are obtained from Estonian Business Register. Failure risk (FR) is portrayed with a well-known Altman et al. (2017) model, while seven variables reflecting corporate governance (CG) based on previous studies have been selected. As the method, logistic regression (LR) is applied with FR in the binary form as a dependent variable and seven CG variables as independent. The effect of firm size and age is studied with two separate LR models. Findings – The results indicate that with the growth in manager’s age and the presence of managerial ownership, failure risk reduces. In turn, the presence of larger boards and managers having directorships in other firms leads to higher failure risk. Gender heterogeneity in the board, board tenure length and ownership concentration by means of having a majority owner are not associated with failure risk. The obtained results vary with firm size and age. Originality/value – Unlike this study, research published on this topic earlier has used a much narrower definition of failure, mostly focused on large and listed companies, been sample based and information about corporate governance variables has often been obtained through questionnaires. All these limitations are relaxed in this population level study. Keywords SMEs, Estonia, Corporate governance, Entrepreneurship and small business management, Private firms, Failure risk Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction The purpose of firms is value creation in a sustainable manner so that they could be successful in the long-run, and thus, the leadership of companies should strive to operate the firm at the minimum in a way it would not fail. Therefore, it is vital to study, how management of firms is linked to their failure. This also enables to interconnect two mainstream areas in the business literature, i.e. corporate governance and failure risk, in a novel setting. Literature focused on firm failure has emerged decades ago and the core of this research stream since the piloting studies by Beaver (1966) and Altman (1968) has been the composition of failure prediction models. Since then, a myriad of different failure prediction models have been composed (Dimitras et al., 1996; Bellovary et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2014). This research stream started in finance domain and therefore most of these studies initially The authors acknowledge financial support from Estonian Ministry of Education and Research grant IUT20-49 “Structural Change as the Factor of Productivity Growth in the Case of Catching up Economies”. Management Research Review Vol. 42 No. 6, 2019 pp. 703-720 © Emerald Publishing Limited 2040-8269 DOI 10.1108/MRR-03-2018-0105 MRR 42,6 704 relied only on financial variables. As the field matured, various corporate governance variables were also included in the models to improve their accuracies (Chaganti et al., 1985; Daily and Dalton, 1994; Platt and Platt, 2012; Iwanicz-Drozdowska et al., 2016; Chan et al., 2016). Until recently, though, the studies about failure risk have mainly focused on large public firms and private small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) segment has been relatively unexplored. However, majority of firms globally are private SMEs and some authors (Altman and Sabato, 2007; Elshahat et al., 2015) argue that the prediction models developed on the example of large public firms are not very effective in case of SMEs, and therefore, separate models are required for that segment. Thus, recent focus in this literature domain has shifted to studying private SMEs (Altman et al., 2017). Still, the available SME failure prediction models mostly cover only financial variables (Pompe and Bilderbeek, 2005; Mselmi et al., 2017), although it is argued that the inclusion of corporate governance variables is particularly important in the SME segment, among others due to the fact that it is difficult to compose high-accuracy prediction models for SMEs based on financial ratios only (Ciampi, 2015). There exist a few studies that have included some non-financial compliance and “event” variables such as delays in filing company reports, existence and contents of audit reports, legal actions by creditors (Altman et al., 2010). Still, there are only a few studies that include specifically corporate governance variables such as owner and board characteristics into failure risk modeling (Ciampi, 2015; Ciampi, 2017). Thus, the effectiveness of corporate governance variables in case of private SME segment is largely unexplored. In general, corporate governance is a system by which companies are directed and controlled (Huse, 2007). It deals with how shareholders of a company can ensure the survival and success of a company given the separation of ownership and control. The directing part deals with creating possibilities for the management to do a better job. It starts with forming a management team that is capable, with complementary skills and effective, but it also means appropriate co-operation with and support for the management team. Upper echelons theory (Hambrick and Mason, 1984; Hambrick, 2007) posits that organizational performance is influenced by the characteristics of its top executives: their personalities, beliefs, capabilities, but also the interactions among the top executives. It could therefore be assumed that failure risk also depends on the characteristics of firm’s upper echelons, i.e. the top managers. The control part of corporate governance stems from agency theory (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Fama and Jensen, 1983), where owners/principals need to monitor and motivate managers/agents to discourage shirking, self-interested behavior and other actions that might destroy value, and thus, increase the risk of failure. This study is directed to merge these two main areas in business research (i.e. firm failure and corporate governance), therefore aiming to study how corporate governance is interconnected with failure risk in case of SMEs. The selected topic is novel in several aspects. While the association of corporate governance and failure has so far been mainly studied by using a very narrow subset of failure, i.e. bankruptcy or permanent insolvency, we take a broader approach and use failure risk as a dependent variable. This enables to provide the study with remarkably wider scope, rather than focusing only on failure reflected through the legal proceedings. As failure risk measure selected for this study incorporates all important financial domains like liquidity, profitability and leverage, this study is also strongly linked to the stream focusing on the interconnection of corporate governance and firm performance. While past research has mainly focused on large and/or listed firms, this study focuses on a relatively underexplored segment of SMEs. Our data set represents the whole population of SMEs in one country, being therefore free from sampling bias. Finally, the information about corporate governance variables is procured from official business register and therefore factual, while previous research has mainly focused on questionnaires. Section 2 outlines the most widely used corporate governance variables having potential effect on firm failure from past studies and sets research questions for the empirical portion of the paper. Section 3 outlines the failure risk and corporate governance variables implemented in this study and also describes the whole population of Estonian SMEs used. Section 4 focuses on study’s empirical results, and Section 5 focuses on discussing them. The study classically ends with a conclusion including limitations, implications and some future research directions in Section 6. 2. Literature review We have systemized the previous literature about the interconnection of failure with board and owner characteristics into seven subsections. These subsections focus on the most widely used variables in the previous studies. As noted earlier, only a few previous studies exist that explore corporate governance variables specifically in the SME context. Therefore, beside SME-specific studies, we have in the literature review section mostly relied on similar studies in the large firm segment and discussed the relevance of their findings in the SME context. When generally the viewed studies have empirically considered different contexts of firm failure, then some theoretical studies and research focusing on firm performance have been referenced as well. The latter is especially topical, when previous evidence about the interconnection of failure risk and specific variable is absent. Each subsection ends with a research question (RQ), which will be studied in the empirical portion of the paper. As specifically in the context selected for this study previous results are either lacking or controversial, we do not set hypotheses indicating the expected behavior of independent variables. Instead, we rely on an exploratory study design to discover the phenomena in the context of SMEs. 2.1 Board size The link between board size and firm failure is often discussed in the literature. However, the topic is controversial and related to the theoretical perspective applied. From the resource dependence point of view (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978), boards with larger number of members add various competences, networks, relationships and resources to the firm, and thus, improve the chances of its survival. Accordingly, some studies have concluded that larger boards decrease the failure risk (Chaganti et al., 1985). On the other hand, larger boards are more susceptible to power games and coalition buildings, which may hamper the speed of decision-making during crisis. Therefore, smaller boards are more effective in that sense. Accordingly, some studies have found that smaller boards improve firm performance, and thus, decrease the failure risk (Yermack, 1996; Eisenberg et al., 1998; Bennedsen et al., 2008; Fich and Slezak, 2008; Paniagua et al., 2018). To explain such discrepancy, some studies point out that whether small or large boards increase or decrease bankruptcy risk, depends on firm characteristics such as size and complexity (Darrat et al., 2016) or industry characteristics such as high or low growth sector (Dowell et al., 2011). Ciampi (2015) studied the effect of board size specifically in the SME context. He hypothesized that board size has a positive correlation with small company failure, however that hypothesis was not confirmed. Based on previous studies the increase in board size could either lead to an increase or decrease in failure risk, and stemming from this, the first research question is: RQ1. How are board size and failure risk interconnected in case of SMEs? Failure risk 705 MRR 42,6 706 2.2 Board gender heterogeneity Upper echelons theory (Hambrick and Mason, 1984; Hambrick, 2007) predicts that actions of board members are influenced by their experiences, values and cognitive frames. Thus, board gender heterogeneity is likely to broaden the information, knowledge and values that are used in decision-making. Furthermore, Post and Byron (2015) argue that having women on boards influences not only what information is used in decision-making but also how this is being done – females are more likely to value interdependence, benevolence and tolerance (Adams and Funk, 2012). Studies have shown that female directors tend to have more university degrees than male directors (Hillman et al., 2002; Carter et al., 2010), they are more likely to be successful in marketing and sales (Groysberg and Bell, 2013), they bring different experiences and understandings about consumer markets (Carter et al., 2003; Campbell and Minguez-Vera, 2008) and their path to board tends to be different from that of males (Hillman et al., 2002; Singh et al., 2008). As a result, board gender heterogeneity is likely to impact firm performance (Carpenter, 2002). Post and Byron (2015) have summarized studies about board heterogeneity and found in their meta-analysis of 140 papers that the relationship between female representation in board and firm financial performance is generally positive, although there are differences between countries stemming from their legal and regulatory context (namely, shareholder protection strength) and socio-cultural background (namely, gender parity in society). Their analysis predicts that having women on board has more positive effect on firm financial performance in countries with higher shareholder protection regulations, because corporate governance processes are considered to be more important in these countries, while weak shareholder protection laws may lessen the focus on corporate governance practices. Gender parity in society influences how seriously women are taken in the board and high gender parity as a contextual factor increases the impact of board heterogeneity on firm performance. Previous studies have not come to a clear conclusion about how board’s gender diversity affects failure risk in case of larger firms. To our knowledge there are no previous studies that analyze the impact of gender diversity on firm failure risk specifically in the SME segment. However, as upper echelons theory is not specific to large firms only, it could be expected that the broader range of views, experiences and cognitive frames that gender diversity creates among the key decision makers could also impact SME performance, and thus, the failure risk. Therefore, the second research question is: RQ2. How are gender heterogeneity and failure risk interconnected in case of SMEs? 2.3 Board tenure Board tenure – time spent in the board of a specific firm – is expected to increase director’s knowledge about the firm and its business environment (Vafeas, 2003) and commitment toward the firm (Buchanan, 1974). As a result, it is expected that directors with a long tenure at a specific firm should improve firm performance, and thus, decrease the risk of failure. On the other hand, some studies have discovered that extensive board tenure may be associated with corporate governance problems (Berberich and Niu, 2011) that ultimately may lead to poorer firm performance, and thus, increase the risk of failure. The third type of studies has found some contingency factors that influence the relationship between board tenure and firm performance. For example Henderson et al. (2006) found that in stable industries (such as food manufacturing) firm performance improves with longer board tenure, while in dynamic industries (such as computers’ manufacturing) the opposite happens. Compared to large firms SMEs have less resources to spend on larger boards and several layers of management. This means that fewer people have to handle more aspects of the business. In case of large firms, many board members can divide the responsibility areas (e.g. finance, marketing, operations). SME boards have fewer members and less support from several layers of management, so each SME board member should be fairly well informed about all aspects of the firm. The longer a board member stays with the firm, the more he or she learns about the firm and its environment. Furthermore, SMEs tend to have less codified knowledge compared to large firms, so it takes more time for new board members to get familiar with all relevant details about the firm. Therefore, it could be expected that board tenure has impact on SME failure risk. Thus, the third research question aims to explore the role of board tenure: RQ3. How are board tenure and failure risk interconnected in case of SMEs? 2.4 Age of top managers Age of top managers can be used as a proxy for how experienced board members are. When the previous variable – board tenure – expresses the firm-specific experience, the age variable relates to a more general life and business experience. Upper echelons theory argues that board characteristics, including the age of board members, manifest in firm actions and therefore influence firm performance. Prior studies have yielded mixed results in respect to the link between age of top managers and firm performance. For example Wang et al. (2016) conclude based on a meta-analysis of 308 studies that CEO age correlates positively with firm performance. On the other hand, it has been found that although the age influences manager’s decisions regarding risk-taking propensity, the result of that on firm performance could be either positive or negative (Bertrand and Schoar, 2003). The direction of correlation also depends on how to measure performance. For example Peni (2014) found that there is a positive relationship between executive age and firm performance when it is measured with ROA, but the relationship is insignificant when measured with Tobin’s Q. To the best of our knowledge there are no prior studies exploring the link between age of top managers and SME failure risk. Given the exploratory nature of this paper we seek to shed light in this matter and therefore the fourth research question is: RQ4. How are top manager’s age and failure risk interconnected in case of SMEs? 2.5 Multiple directorships Board members may hold director positions in several firms at the same time. Having several director positions may signal director quality and superior performance (Fama and Jensen, 1983; Ferris et al., 2003), and thus, should decrease the failure risk of a company. Such positive correlation between firm performance and multiple directorships of board members has been established in several prior studies (Geletkanycz and Boyd, 2011; Carpenter and Westphal, 2001). On the other hand, being involved in many companies at the same time may fragment director’s focus and may create a potential for shirking (Core et al., 1999; Jiraporn et al., 2008; Berberich and Niu, 2011), and as a result, multiple directorships may increase the failure risk. It is sometimes also a practice for defaulting (SME) firms to hire a new board member to go through the bankruptcy process so that the original ownermanager can save their face and have a clean track record. Thus, a person with a very large number of simultaneous directorships may also indicate a potential failure risk. To resolve Failure risk 707 MRR 42,6 the controversial issue of how holding multiple director positions and failure risk are associated in case of SMEs, the fifth research question is: RQ5. How are multiple directorships and failure risk interconnected in case of SMEs? 708 2.6 Ownership concentration Firms with concentrated ownership have one or a few large shareholders that own majority of shares in the firm. Such large shareholders in private firms tend to have most of their wealth and income connected to the firm (Ciampi, 2015). That makes them especially interested in the performance of the specific firm. They monitor activities of managers and performance of the firm more actively and effectively than in case of dispersed ownership (Shleifer and Vishny, 1986). Such scrutiny reduces shirking and self-serving behavior of managers (Jensen and Meckling, 1976) and thus reduces potentially value destructive activities, i.e. decreases failure risk. Previous studies provide mixed evidence regarding the link between ownership concentration and failure risk. Some studies find that concentrated ownership is positive for firm performance, i.e. it reduces failure risk (Perrini et al., 2008; Kapopoulos and Lazaretou, 2007; Pursey et al., 2009; Paniagua et al., 2018). Other studies (Thomsen and Pedersen, 2000; De Miguel et al., 2004) have established a bell-shaped non-linear association between ownership concentration and performance. A third set of studies (Demsetz and Villalonga, 2001) has concluded that the relationship between ownership structure and firm performance is insignificant. In his study of 934 Italian SMEs, Ciampi (2015) found that in case of SMEs there is a significant negative correlation between ownership concentration and company default. Our dependent variable – failure risk – is broader than Ciampi’s firm default. Logically, it could be expected that ownership concentration also has influence on the broader failure risk, and to disclose this phenomenon, our sixth research question is: RQ6. How are ownership concentration and failure risk interconnected in case of SMEs? 2.7 Managerial ownership Two separate forces are expected to influence the relationship between managerial ownership and failure risk. Convergence-of-interest hypothesis posits that as the portion of shares owned by managers increases, their interests with other shareholders converge, which should result in avoidance of value destructive behaviors predicted by agency theory (Morck et al., 1998), i.e. higher proportion of shares held by managers should decrease the failure risk. Entrenchment hypothesis, however, states that when the proportion of shares held by managers is substantial to give them enough voting power or influence, they might start to maximize their personal objectives at the expense of other shareholders, which could be harmful for the firm as the whole, and thus, increase its failure risk (Morck et al., 1998). Previous studies have established a non-linear relationship between managers’ shareholding proportion and firm performance. Some studies (McConnell and Servaes, 1990; Han and Suk, 1998; Coles et al., 2012) have found a quadratic relationship between the size of managerial ownership and firm performance, i.e. initially firm performance improves as managerial ownership increases due to the convergence-of-interest effect and after a certain point the performance decreases due to the entrenchment effect. Other studies (Morck et al., 1998; Short and Keasey, 1999; De Miguel et al., 2004) have found the relationship between firm performance and managerial ownership to be more complex (in the cubic form), where initially the performance improves as the managerial ownership increases, at a certain point the performance starts to decrease and at very high managerial ownership levels starts to increase again. The relationship between managerial ownership and failure risk has not been studied specifically in case of SMEs, and thus, to disclose the connection between managerial ownership and failure risk, the seventh research question is: RQ7. How are managerial ownership and failure risk interconnected in case of SMEs? 3. Data, variables and method The analysis is based on 67,058 Estonian SMEs, using data procured from the Estonian Business Register (EBR), which contains firms’ annual reports and up to date information about firms’ boards and owners. Estonian Commercial Code (2018) permits several legal forms for firms. Two main legal forms are Private Limited Company (in Estonian “osaühing”, i.e. OÜ, later referred to as PrLC) and Public Limited Company[1] (in Estonian “aktsiaselts”, i.e. AS, later referred to as PuLC). Other types (General Partnership, Limited Partnership and Commercial Association) are relatively rare in practice. Our sample consists of 64,561 PrLC-s (96.3 per cent of sample) and 2,497 PuLC-s (3.7 per cent of sample). In terms of corporate governance, PrLCs have a very simple structure where the firms are governed by a one-tier board, which is subject to firms’ owners. The board members have legal right to do transactions on behalf of the firm. PuLC type of firms have a two-tier board with a clear separation of supervisory board and management board. The management board is responsible for daily management of the firm. It reports to the supervisory board and not directly to shareholders. The role of supervisory board is to plan the activities and organize the management of the firm and supervise the activities of the management board. The consent of supervisory board is required for transactions beyond the scope of everyday activities of the firm. Members of one board cannot be members of the other board at the same time (which eliminates one of the key variables usually analyzed in corporate governance analyses, namely the CEO-duality). Estonia is a member of European Union (EU) since 2004, which means that Estonian legislative system and key institutions are harmonized with overall EU regulations, which increases the comparability of Estonian SMEs to firms with comparable sizes from other EU countries. Globally, Estonia ranks high in several business rankings, for example in World Bank (2018) Doing Business rankings Estonia has 12th place in “Ease of doing business” and “Starting a business”, 11th place for “Enforcing contracts” and 14th place for “Paying taxes”. These rankings place Estonia in the same range with countries like Finland, Sweden and Norway. So also in terms of general business environment Estonia is quite comparable to other Northern European countries. The focus in this study is on private SMEs (not exceeding the EU set size limits for these firms[2]). The median SME in the population of 67,058 Estonian SMEs used in the analysis is a very small firm, with total balance sheet of e33,000 and age 7.5 years at the balance sheet closing date. For 98 per cent of firms total assets remain below e2m; thus, these firms are classified as micro firms. The largest firm in the analysis has total assets e40.2m. The age distribution of firms indicates that a 1st percentile firm is 0.65 and 99th percentile firm 19.6 years old, the first and third quartiles being 3.59 and 13.08 years, respectively. The highly aggregate sectoral breakdown of observations is as follows: 7.1 per cent primary, 9.5 per cent manufacturing, 18.4 per cent construction, 18.8 per cent sales and 46.2 per cent service sector firms. Failure risk 709 MRR 42,6 710 The variables used in the analysis with their coding and calculation details have been presented in Table I. Seven independent variables are applied, which reflect the domains outlined in the literature review. Most of the independent variables have been calculated based on their common usage in the literature, although we acknowledge that some domains are used less in the literature, and thus, the specific variables portraying them (e.g. BTENURE and MDIRECT) are not as frequent as others. For calculating the dependent variable portraying failure risk, we will use the most universally applicable failure prediction study by Altman et al. (2017). This multisector study included millions of European firms for estimation and has a high classification accuracy in Estonia, thus being directly applicable for this study. Moreover, there are no multi-sector models available in the Estonian scientific literature. We will apply Model 2 from Altman et al. (2017) study, which is the only logit model without control variables (see Table AI for this model). For each firm, we have detected whether the failure risk is over 0.5 (i.e. 50 per cent) based on this model, leading to the binary dependent variable SCORE. The firms with failure risk >0.5 will be coded with 1, the opposite situation with 0 respectively. Unlike previous failure prediction studies, we use a broader term of failure (i.e. having >50 per cent of failure risk, not for instance the bankruptcy fact), which enables better linking of the results with the research focusing on firm performance. Altman et al. (2017) model includes all main financial domains, such as liquidity, profitability (annual and accumulated) and leverage. Thus, when a firm has failure risk over 50 per cent, it is evident that it is performing poorly at least in one of these domains. In the sample of 67,058 Estonian SMEs, 12,219 firms have SCORE = 1, i.e. failure risk over 50 per cent based on Altman et al. (2017) model. From EBR we use all firms in analysis, for which the dependent and independent variables could be calculated. Thus, the sample represents the majority of Estonian active firm population, which according to Statistics Estonia for the selected year was 79,668. We have chosen year 2015 for Variable domain Variable coding Calculation Board size (IV) Board gender heterogeneity (IV) Board tenure (IV) BSIZE BGENDER Number of board members in the firm If both genders are present in the board then 1, otherwise 0 BTENURE Ratio of tenure’s time of the longest serving board member and firm agea Biological age of the oldest board member Age of top managers (IV) Multiple directorships (IV) Ownership concentration (IV) Managerial ownership (IV) Failure risk (DV) MAGE MDIRECT OCONC MOWN SCORE The number of board memberships the board members altogether have in other firmsb If one owner has over 50% of the shares then 1, otherwise 0 Ratio of share capital owned by board members to total share capital 0 if Altman et al. (2017) Model 2 transformed logit score #0.5, 1 if Altman et al. (2017) Model 2 transformed logit score >0.5 Notes: IV – independent variable, DV – dependent variable; athe maximum of the ratio is 1, indicating that Table I. the longest serving board member has been in the firm for the whole firm lifetime. bIf a firm has, for Variables used in the instance, two board members, and both of them are board members in another firm as well, the value for the analysis variable is 2 analysis, as this is the last year during the study’s composition about which we could obtain information. In such study design, we can use only a single year, as the boards and owners of SMEs do not change often, making the values of independent variables repeat in case of using multiple years. As binary dependent variable (SCORE) is concerned, we will use logistic regression method with other variables listed in Table I as independent variables. Logistic regression is the most widely used method in case of binary dependent variables, therefore suiting for this study well. Marginal effects of independent variables and multicollinearity statistics are also provided. Firm size and age effects on corporate governance variables are considered with two separate logistic regression models. Namely, the firm population is divided into two based on either firm size (total assets in 2015) or age (time from foundation to the end of year 2015) and additional logistic regression models are composed (see Table AII and Table AIII). As 98 per cent of the firms are micro firms by size, the usage of for instance quartiles in dividing the population is not reasonable. Failure risk 711 4. Empirical results Descriptive statistics (see Table II) indicate that the median firm in the data set has one 45year-old board member, who has been in the board for the whole firm’s lifetime and is also the majority owner of the firm. Concerning BSIZE, 74 per cent of firms have single-person boards, while 22.1 per cent of boards have two persons. Thus, a vast majority of boards are non-heterogeneous and only in case of 11.6 per cent of boards BGENDER = 1. Board members have mostly no or a few other business ties, namely MDIRECT = 0 for 44.9 per cent of observations, 1 for 23.1 per cent and 2 for 12.2 per cent. For 81.1 per cent of firms there is a majority owner (OCONC = 1). The median age of oldest board member (MAGE) is 45 years, the first and third quartiles being 37.3 and 54.2 years, respectively. In 80 per cent of firms, the oldest serving board member (BTENURE) has been there at least for 90 per cent of firm’s lifetime and owns (MOWN) 100 per cent of the firm. Preliminary statistical tests (Table II) for studied seven variables indicate, that two of them (BGENDER and BTENURE) SCORE 0, (N = 54839) Statistic Mean Std. deviation Median Minimum Maximum 1, (N = 12219) Mean Std. deviation Median Minimum Maximum Total, (N = 67058) Mean Std. deviation Median Minimum Maximum BSIZE BGENDER MAGE MDIRECT BTENURE OCONC MOWN 1.30 0.56 1.00 1.00 7.00 1.32 0.58 1.00 1.00 6.00 1.31 0.57 1.00 1.00 7.00 0.12 0.32 0.00 0.00 1.00 0.12 0.32 0.00 0.00 1.00 0.12 0.32 0.00 0.00 1.00 46.22 11.70 45.24 17.62 93.60 45.77 11.59 44.75 18.93 92.28 46.14 11.68 45.14 17.62 93.60 1.47 2.16 1.00 0.00 10.00 1.57 2.28 1.00 0.00 10.00 1.49 2.18 1.00 0.00 10.00 0.90 0.22 1.00 0.03 1.00 0.90 0.22 1.00 0.03 1.00 0.90 0.22 1.00 0.03 1.00 0.81 0.39 1.00 0.00 1.00 0.80 0.40 1.00 0.00 1.00 0.81 0.39 1.00 0.00 1.00 0.89 0.27 1.00 0.00 1.00 0.87 0.30 1.00 0.00 1.00 0.88 0.28 1.00 0.00 1.00 Notes: For BSIZE, MAGE, MDIRECT, MOWN the Brown-Forsyth ANOVA test (p-value < 0.01) for BTENURE 0.589 (with SCORE as factor). For BGENDER Pearson chi-square test p-value 0.941, for OCONC 0.000 (with SCORE as other variable in contingency test) Table II. Descriptive statistics of variables MRR 42,6 712 do not associate with failure risk[3]. Thus, it could be suspected that these variables are not significant in the follow-up logistic regression analysis. The logistic regression analysis conducted (Table III) indicates that as expected based on the statistical tests, BGENDER and BTENURE, but also ownership concentration (OCONC) do not associate with failure risk. In turn, four variables out of seven are significant, namely the rise in two variables (board size, i.e. BSIZE, and multiple directorships, i.e. MDIRECT) increases failure risk, and in turn, the rise in two variables (manager’s age, i.e. MAGE, and manager’s ownership, MOWN) decreases failure risk. The resulting logit model is significant and free from multicollinearity (VIF values in Table III are below 2.00). The robustness of the initial model is tested with bootstrapping (Table III, final columns), which indicates that the coefficients of all significant variables remain with the same signs. We also tested a model in case of multiple person boards (i.e. BSIZE > 1), which excludes the majority of “single person” firms. With such restriction, less than half (46.8 per cent) of the firms have a majority owner. All variables remain (in)significant and with same signs similarly to the base model in Table III, except for BSIZE. The latter is a logical result, as in the model presented in Table III, the significance of the variable is determined by the difference in between single- and multi-person boards. Moreover, the multi-person board sample is dominated by two-person board observations (84.8 per cent). When the firm population is divided into two based on size and separate logistic regression models composed, it can be seen that size has an effect on the performance of independent variables. Larger boards are unfavorable only for the smaller firms, while the variable is insignificant in case of larger SMEs. Multiple directorships increases failure risk in both size groups, the negative effect being stronger in case of larger SMEs. Managerial ownership decreases failure risk in both size groups, whereas with growth in firms’ size the variable’s risk reduction effect becomes remarkably larger. Board heterogeneity, ownership concentration and top manager’s age are insignificant in both size groups, while the latter variable was significant in the base model. Board tenure is insignificant in case of larger SMEs, while it is decreasing failure risk in the smaller size group, but the variable is not as significant as others. The analysis of two firm age groups indicates that likewise with size, age has an effect on the performance of independent variables. Larger boards are unfavorable only for younger firms, while the variable is insignificant in case of older firms. Multiple directorships variable acts in the same way, increasing failure risk for younger firms, but being insignificant in case of older firms. Managerial ownership decreases failure risk in both age Variable Table III. Logistic regression model BSIZE BGENDER MAGE MDIRECT BTENURE OCONC MOWN CONSTANT B 0.066 0.042 0.004 0.015 0.037 0.035 0.258 1.187 S.E. Wald 0.024 7.486 0.037 1.308 0.001 23.792 0.005 10.680 0.047 0.619 0.030 1.318 0.037 49.043 0.072 270.967 Sig. dy/dx VIF Lower BS interval Higher BS interval BS Sig. 0.006 0.253 0.000 0.001 0.431 0.251 0.000 0.000 0.010 0.006 0.001 0.002 0.006 0.005 0.038 1.98 1.39 1.05 1.10 1.07 1.46 1.15 0.017 0.116 0.006 0.006 0.061 0.089 0.328 1.325 0.116 0.031 0.003 0.024 0.133 0.025 0.183 1.045 0.008 0.260 0.001 0.001 0.452 0.234 0.001 0.001 Notes: Model LR chi-square 107 (p-value = 0.000) and log likelihood 31,781. Bootstrapping (BS) results obtained with 1,000 bootstrap samples. Dependent variable SCORE groups, the effect being stronger in case of younger firms. Board heterogeneity, board tenure, ownership concentration and top manager’s age are insignificant in both age groups, while the latter variable was significant in the base model. 5. Discussion of findings Our analysis deals specifically with SMEs and the findings should be interpreted with that contingency in mind. Looking at the independent variables either separately or in groups, allows outlining some important trends (see Table IV for the summary of findings about the research questions). The results show that SMEs have higher (lower) failure risk when their boards are larger (smaller). This finding supports the strand of literature (Yermack, 1996; Eisenberg et al., 1998; Bennedsen et al., 2008; Fich and Slezak, 2008) that stresses the importance of faster decisions and warns about the risks of power games that might be characteristic to larger boards. Different viewpoints, larger networks and relationships that the proponents of larger boards promote, seem to have less importance in the SME segment. In case of larger and older firms, board size is insignificant, i.e. deeper board discussions enabled by larger boards start to balance the value of faster decisions that smaller boards bring. As board gender heterogeneity is not associated with SME failure risk, it also indicates that different perspectives that come from having both genders represented in the board have lower importance in the SME segment. Gender heterogeneity variable remains insignificant also when controlling for firm size or age. Although large and heterogeneous boards could provide more balanced decisions, these can be slower due to longer time requirements for harmonizing different views, and thus, in case of SMEs the speed of decisions that comes from smaller boards irrespective of gender composition seems to matter. Also, as the base risk of failure is higher for SMEs than for large firms (Altman et al., 2017), SMEs are more frequently in crisis situation and often need prompt decisions for survival. Variables reflecting board tenure and age of top managers both deal with experience factor in running the firm. While the former shows the specific firm-related experience, the latter is related to a more general life and business experience of top managers. Our analysis shows that in case of SMEs, only the general experience (as represented by CEO age) is a significant determinant of failure risk. Specifically, more life and business experience Research question Result RQ1. Board size RQ2. Board gender heterogeneity RQ3. Board tenure Failure risk increases with the increase in board size Failure risk is irrelevant to whether boards are gender homo- or heterogeneous Failure risk is irrelevant to how long from firm lifetime the longest serving board member has been on its position Failure risk decreases with the increase in the biological age of oldest manager Failure risk increases with the increase in the number of other board memberships Failure risk is irrelevant to whether there is a majority owner RQ4. Top manager’s age RQ5. Multiple directorships RQ6. Ownership concentration RQ7. Managerial ownership Failure risk decreases with the increase of share capital owned by board members Note: The results of the research questions rely on the results in the base model presented in Table III Failure risk 713 Table IV. Results of research questions MRR 42,6 714 decreases the failure risk. Specific firm experience, on the other hand, is insignificant in that respect. Interestingly still, when analyzing the issue in size groups, then in case of the smaller SMEs the managerial general life and business experience (MAGE) seems not to matter that much, but the firm-specific experience (as measured by BTENURE) is more relevant. The explanation could be, that in very small firms it matters more, whether the manager is competent in the specific business area, rather than having a more broader and general knowledge. Multiple directorships have two-fold effect on the firm. Being involved with many firms equips the manager with a broader network, new ideas and possibilities to gain wider experience. At the same time it leaves the manager less time to deal with any single firm it is associated with. Our results show that in case of SMEs, multiple directorships increases the failure risk, which has been proposed in previous studies (Core et al., 1999; Jiraporn et al., 2008; Berberich and Niu, 2011). This finding indicates that in case of SMEs the focus factor might be more important than gathering wider experience and network from other firms. Given that SME boards tend to be much smaller than the ones of large firms (in our sample, the median board size was one person), the price of distraction is much higher for SMEs because there are less board members to compensate for the lost time of that board member who is dealing with the issues of another firm. The analysis by size groups shows that the negative impact of multiple directorships is stronger in the bigger SME group, which could be explained by the need to contribute more time in case of larger firms, where the business process is more elaborate and properly managing the firm needs stronger focus. An additional interesting aspect rises from the analysis by age groups. Namely, multiple directorships increases failure risk only in case of younger firms, while it is insignificant in case of older firms. The underlying logic for this could be that younger firms need more managerial focus to get the business running, processes established, resource base built and clients won. At a certain point the firm is sufficiently set up so that the top manager can start delegating more and spend more time on other firms, but the latter does not transfer in any way to the wellbeing of the firm under question. Ownership concentration and managerial ownership variables deal with the role of owners in running the firm. More specifically, concentrated ownership variable indicates whether or not there is a single majority owner who can have substantial impact on the decisions that the managers take (for example by single-handedly hiring and firing the managers). Managerial ownership takes it one step further and shows the overlap between owners and managers. If the overlap is large (88 per cent in our data set), it means that the classical agency problem between owners and managers is reduced and the convergence-ofinterest hypothesis (Morck et al., 1998) prevails. Our results show that while ownership concentration is an insignificant determinant of failure risk, the managerial ownership variable is significant, meaning that high overlap between managers and owners reduces failure risk in case of SMEs. The analysis by size and age groups shows that the failure risk reduction from having managerial ownership is relatively stronger in case of larger and younger SME groups. In terms of firm age, the possible interpretation could be that younger firms need a clear focus from the founder (owner) to get up and running. Having separate non-owner managers might create a potential divergence of interests between owners and hired managers, which in turn makes the decision process slower and thus increases the failure risk. When SMEs get older and more established, the negative effect of having nonowner managers decreases. This logic bears resemblance to the speed versus balanced decisions discussion above in case of board size and heterogeneity variables. The interpretation of size groups’ results could in a way be similar to the logic of multiple directorships discussion. The larger SME group benefits relatively more from the focused and well-motivated owner-managers, as the business is more complex in that group than in the smaller SME group. 6. Conclusions The aim of this study was to explore how corporate governance variables are interconnected with failure risk in case of SMEs. We applied a sample of 67,058 Estonian SMEs to calculate seven different corporate governance characteristics and failure risk based on a well-known universal Altman et al. (2017) failure prediction model. The results indicate, that with the growth in manager’s age and the presence of managerial ownership, failure risk reduces. In turn, larger boards and managers having directorships in other firms lead to a higher failure risk. Gender heterogeneity in the board, board tenure length and ownership concentration by means of having a majority owner are not associated with failure risk. Firm size or age can have an effect on how the corporate governance variables impact failure risk. This study makes several important contributions to the literature. Firstly, it focuses on the relationship between corporate governance variables and firm failure specifically in the SME context, which is a relatively underexplored area, even despite the importance of SMEs in the world economy. Secondly, our study uses a very large whole population data set (67,058 firms) giving more weight to the statistical validity of the results. Thirdly, both the corporate governance and financial data used in the analysis are retrieved from the official agency, i.e. Estonian Business Registry. This further improves the validity of our results by eliminating an important limitation many previous studies suffer from, namely data collection via surveys and the resulting self-reporting bias. We would also like to highlight some of the practical implications from our analysis for owners and managers of SMEs. It appears that SMEs that are run by owner-managers (where the managerial ownership is high) tend to have lower failure risk. Therefore, entrepreneurs who are planning to start a small business or already own one, should be cautious when aiming to hire an outside CEO. Most likely the owner of the small business should be ready to act as the executive of the firm for an extended period of time. Also, it seems that smaller boards tend to have lower failure risk, but only in case multiple directorships are avoided. The latter means that if a small firm owner plans to establish additional firm(s), he will have to fragment the focus between those firms, or hire an outside CEO, both of which scenarios increase the failure risk. There are also some implications for external institutions such as legislators and financiers. For legislators it would be important to note that firm size and age moderate the impact of certain corporate governance variables on SME performance. This means that it might be beneficial for the society to have different regulations for firms depending on their size and/or age. For example, legislators could encourage larger firms to have larger boards while not requiring smaller firms to have such large boards (as that would increase their failure risk). Similarly, external finance providers (in the case of SMEs most likely banks or other trade credit providers) might benefit from including corporate governance variables together with firm size and age information in their decision algorithms as these improve the accuracy of the performance forecast models of SMEs. The latter is especially important in case (timely) financial information about the firm is not available. This study is subject to several limitations. First, it focuses on a single country, so further research is needed in other environments to validate the results on an international scale. Second, even though our analysis covers specifically the SME segment, it should be noted that the segment itself is fairly heterogeneous in terms of size ranging from really tiny micro-firms to relatively established firms of up to 250 employees and assets of e43m. Due to the economic structure of Estonia, the majority of firms in our data set are very small Failure risk 715 MRR 42,6 716 (micro firms). It is possible that different factors are prevalent in the larger end of SME spectrum and further research should test and verify this in different data sets consisting of bigger SMEs. Third, several SMEs in our sample are likely to be family firms where (some of) the owners and board members are relatives. This could moderate the linkages between various corporate governance variables and failure risk. Unfortunately, information about family ties was not present in our data; thus, exploring the effect of family relations could be an interesting avenue of future research. Notes 1. Not to be confused with public firm in the sense of being traded at the stock market. Majority of PuLC type firms are private, i.e. they are not traded at the stock market (there were only 15 firms listed on Tallinn Stock Exchange main list in August 2018). 2. Less than 250 workers and balance sheet total # 43 million euros. 3. To enhance the textual flow of the results and discussion part, we will use in these sections increase/decrease failure risk, instead of the longer version increase/decrease the probability of belonging to the group of firms in failure risk. References Adams, R.B. and Funk, P. (2012), “Beyond the glass ceiling: does gender matter?”, Management Science, Vol. 58 No. 2, pp. 219-235. Altman, E.I. (1968), “Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 23 No. 4, pp. 589-609. Altman, E.I. and Sabato, G. (2007), “Modeling credit risk for SMEs: evidence from the US market”, Abacus, Vol. 43 No. 3, pp. 332-357. Altman, E.I., Sabato, G. and Wilson, N. (2010), “The value of non-financial information in SME risk management”, The Journal of Credit Risk, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 95-127. Altman, E.I., Iwanicz-Drozdowska, M., Laitinen, E.K. and Suvas, A. (2017), “Financial distress prediction in an international context: a review and empirical analysis of Altman’s Z-score model”, Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting, Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 131-171. Beaver, H.W. (1966), “Financial ratios as predictors of failure”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 4, pp. 71-111. Bellovary, J.L., Giacomino, D.E. and Akers, M.D. (2007), “A review of bankruptcy prediction studies: 1930 to present”, Journal of Financial Education, Vol. 33 No. 4, pp. 3-41. Bennedsen, M., Kongsted, H.C. and Nielsen, K.M. (2008), “The causal effect of board size in the performance of small and medium-sized firms”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 32 No. 6, pp. 1098-1109. Berberich, G. and Niu, F. (2011), “Director business, director tenure and the likelihood of encountering corporate governance problems”, CAAA Annual Conference 2011, available at: https://papers. ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1742483 Bertrand, M. and Schoar, A. (2003), “Managing with style: the effect of managers on firm policies”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118 No. 4, pp. 1169-1208. Buchanan, B. (1974), “Building organizational commitment: the socialization of managers in work organizations”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 19 No. 4, pp. 533-546. Campbell, K. and Minguez-Vera, A. (2008), “Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 83 No. 3, pp. 435-451. Carpenter, M.A. (2002), “The implications of strategy and social context for the relationship between top management team heterogeneity and firm performance”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 275-284. Carpenter, M.A. and Westphal, J.D. (2001), “The strategic context of external network ties: examining the impact of director appointments on board involvement in strategic decision making”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 44 No. 4, pp. 639-660. Carter, D.A., Simkins, B.J. and Simpson, W.G. (2003), “Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value”, The Financial Review, Vol. 38 No. 1, pp. 33-53. Carter, D.A., D’Souza, F., Simkins, B.J. and Simpson, W.G. (2010), “The gender and ethnic diversity of US boards and board committees and firm financial performance”, Corporate Governance: An International Review, Vol. 18 No. 5, pp. 396-414. Chaganti, R.S., Mahajan, V. and Sharma, S. (1985), “Corporate board size, composition, and corporate failures in retailing industry”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 400-417. Chan, C.-Y., Chou, D.-W., Lin, J.-R. and Liu, F.-Y. (2016), “The role of corporate governance in forecasting bankruptcy: pre- and post-SOX enactment”, The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, Vol. 35, pp. 166-188, available at: www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/S1062940815000959 Ciampi, F. (2015), “Corporate governance characteristics and default prediction modeling for small enterprises. an empirical analysis of Italian firms”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 68 No. 5, pp. 1012-1025. Ciampi, F. (2017), “The potential of top management characteristics for small enterprise default prediction modeling”, WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 397-408. Coles, J.L., Lemmon, M.L. and Meschke, J.F. (2012), “Structural models and endogeneity in corporate finance: the link between managerial ownership and corporate performance”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 103 No. 1, pp. 149-168. Core, J., Holthausen, R. and Larcker, D. (1999), “Corporate governance, chief executive compensation, and firm performance”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 51 No. 3, pp. 371-406. Daily, C.M. and Dalton, D.R. (1994), “Bankruptcy and corporate governance: the impact of board composition and structure”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 37 No. 6, pp. 1603-1617. Darrat, A.F., Gray, S., Park, J.C. and Wu, Y. (2016), “Corporate governance and bankruptcy risk”, Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 163-202. De Miguel, A., Pindado, J. and de la Torre, C. (2004), “Ownership structure and firm value: new evidence from Spain”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 25 No. 12, pp. 1199-1207. Demsetz, H. and Villalonga, B. (2001), “Ownership structure and corporate performance”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 209-233. Dimitras, A.I., Zanakis, S.H. and Zopounidis, C. (1996), “A survey of business failures with an emphasis on prediction methods and industrial applications”, European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 90 No. 3, pp. 487-513. Dowell, G.W.S., Shackell, M.B. and Stuart, N.V. (2011), “Boards, CEOs, and surviving a financial crisis: evidence from the internet shakeout”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 32 No. 10, pp. 1025-1045. Eisenberg, T., Sundgren, S. and Wells, M.T. (1998), “Larger board size and decreasing firm value in small firms”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 48 No. 1, pp. 113-139. Elshahat, I., Elshahat, A. and Rao, A. (2015), “Does corporate governance improve bankruptcy prediction?”, Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 107-119. Estonian Commercial Code (2018), available at: www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/Riigikogu/act/519122017001/ consolide (accessed 08.08.18). Failure risk 717 MRR 42,6 718 Fama, E. and Jensen, M. (1983), “Separation of ownership and control”, The Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 301-325. Ferris, S.P., Jagannathan, M. and Pritchard, A.C. (2003), “Too busy to mind the business? Monitoring by directors with multiple board appointments”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 58 No. 3, pp. 1087-1111. Fich, E.M. and Slezak, S.L. (2008), “Can corporate governance save distressed firms from bankruptcy? An empirical analysis”, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, Vol. 30 No. 2, pp. 225-251. Geletkanycz, M.A. and Boyd, B.K. (2011), “CEO outside directorships and firm performance: a reconciliation of agency and embeddedness views”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 54 No. 2, pp. 335-352. Groysberg, B. and Bell, D. (2013), “Dysfunction in the boardroom”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 91 No. 5, pp. 89-97. Hambrick, D.C. (2007), “Upper echelons theory: an update”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32 No. 2, pp. 334-343. Hambrick, D.C. and Mason, P.A. (1984), “Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 193-206. Han, K. and Suk, D. (1998), “The effects of ownership structure on firm performance: additional evidence”, Review of Financial Economics, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 143-155. Henderson, A.D., Miller, D. and Hambrick, D.C. (2006), “How quickly do CEOs become obsolete? Industry dynamism, CEO tenure, and company performance”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 27 No. 5, pp. 447-460. Hillman, A.J., Cannella, A.A. and Harris, I.C. (2002), “Women and racial minorities in the boardroom: how do directors differ?”, Journal of Management, Vol. 28 No. 6, pp. 747-763. Huse, M. (2007), Boards, Governance and Value Creation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Iwanicz-Drozdowska, M., Laitinen, E.K., Suvas, A. and Altman, E.I. (2016), “Financial and nonfinancial variables as long-horizon predictors of bankruptcy”, The Journal of Credit Risk, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 49-78. Jensen, M.C. and Meckling, W.H. (1976), “Theory of the firm: managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 305-360. Jiraporn, P., Kim, Y.S. and Davidson, W.N. (2008), “Multiple directorships and corporate diversification”, Journal of Empirical Finance, Vol. 15 No. 3, pp. 418-435. Kapopoulos, P. and Lazaretou, S. (2007), “Corporate ownership structure and firm performance: evidence from Greek firms”, Corporate Governance: An International Review, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 144-154. McConnell, J. and Servaes, H. (1990), “Additional evidence on equity ownership and corporate value”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 595-612. Morck, R., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (1998), “Management ownership and market valuation: an empirical analysis”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 293-315. Mselmi, N., Lahiani, A. and Hamza, T. (2017), “Financial distress prediction: the case of French small and medium-sized firms”, International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 50, pp. 67-80. Paniagua, J., Rivelles, R. and Sapena, J. (2018), “Corporate governance and financial performance: the role of ownership and board structure”, Journal of Business Research, Online First Version, Vol. 89, pp. 229-234. Peni, E. (2014), “CEO and chairperson characteristics and firm performance”, Journal of Management and Governance, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 185-205. Perrini, F., Rossi, G. and Roverra, B. (2008), “Does ownership structure affect performance? Evidence from the Italian market”, Corporate Governance: An International Review, Vol. 16 No. 4, pp. 312-325. Pfeffer, J. and Salancik, G.R. (1978), The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Approach, Harper and Row Publishers, New York, NY. Platt, H. and Platt, M. (2012), “Corporate board attributes and bankruptcy”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 65 No. 8, pp. 1139-1143. Pompe, P.P.M. and Bilderbeek, J. (2005), “The prediction of bankruptcy of small- and medium-sized industrial firms”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 20 No. 6, pp. 847-868. Post, C. and Byron, K. (2015), “Women on boards and firm financial performance: a meta-analysis”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 58 No. 5, pp. 1546-1571. Pursey, P., Heugens, R., Essen, M. and Oosterhout, J. (2009), “Meta-analyzing ownership concentration and firm value in Asia: towards a more find-grained understanding”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 481-512. Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1986), “Large shareholders and corporate control”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 94 No. 3 Part 1, pp. 461-489. Short, H. and Keasey, K. (1999), “Managerial ownership and the performance of firms: evidence from the UK”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 79-101. Singh, V., Terjesen, S. and Vinnicombe, S. (2008), “Newly appointed directors in the boardroom: how do women and men differ?”, European Management Journal, Vol. 26 No. 1, pp. 48-58. Sun, J., Li, H., Huang, Q.-H. and He, K.-Y. (2014), “Predicting financial distress and corporate failure: a review from the state-of-the-art definitions, modeling, sampling, and featuring approaches”, Knowledge-Based Systems, Vol. 57, pp. 41-56. Thomsen, S. and Pedersen, T. (2000), “Ownership structure and economic performance in the largest european companies”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 21 No. 6, pp. 689-705. Vafeas, N. (2003), “Length of board tenure and outside director independence”, Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, Vol. 30 No. 7, pp. 1043-1064. Wang, G., Holmes, R.M., Oh, I.-S. and Zhu, W. (2016), “Do CEOs matter to firm strategic actions and firm performance? A meta-analytic investigation based on upper Echelons theory”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 69 No. 4, pp. 775-862. World Bank (2018), “Doing business 2018. Reforming to create jobs”, available at: www.doingbusiness. org/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2018 (accessed: 08.08.18). Yermack, D. (1996), “Higher market valuation of companies with small board of directors”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 40 No. 2, pp. 185-211. Corresponding author Oliver Lukason can be contacted at: oliver.lukason@ut.ee Failure risk 719 MRR 42,6 Appendix Variable Coefficient 720 (Current assets – current liabilities)/total assets (i.e. WCTA) Retained earnings/total assets (i.e. RETA) Earnings before interest and taxes/total assets (i.e. EBITTA) Book value of equity/total debt (i.e. BVETD) Constant Table AI. Altman et al. (2017) Model 2 used to calculate failure risk Note: For each firm, failure risk has been calculated as follows and coded as 1, when p > 0.5, and 0 1 otherwise: p ¼ 1þe1 L ¼ 1þeðConstant0:495WCTA0:862RETA1:721EBITTA0:017BVETD Þ Source: Altman et al. (2017; p. 154) Variable Table AII. Two logistic regression models to portray the effect of firm size on the results BSIZE BGENDER MAGE MDIRECT BTENURE OCONC MOWN Constant B 0.159 0.114 0.001 0.031 0.181 0.029 0.221 0.974 Total assets # e32,921 S.E. Wald 0.034 0.048 0.001 0.007 0.065 0.040 0.050 0.096 22.375 5.629 0.225 17.680 7.809 0.505 19.220 102.337 Sig. B 0.000 0.018 0.635 0.000 0.005 0.477 0.000 0.000 0.019 0.018 0.001 0.072 0.059 0.001 0.416 1.685 Total assets > e32,921 S.E. Wald 0.036 0.058 0.002 0.006 0.072 0.047 0.055 0.114 0.277 0.092 0.130 129.596 0.670 0.001 56.543 220.169 Sig. 0.599 0.761 0.719 0.000 0.413 0.978 0.000 0.000 Notes: The initial firm population is divided into two, the median firm size (total assets in the year 2015) being the breakeven point. Both subpopulations include an equal number of 33,529 firms Variable Table AIII. Two logistic regression models to portray the effect of firm age on the results 0.495 0.862 1.721 0.017 0.035 BSIZE BGENDER MAGE MDIRECT BTENURE OCONC MOWN Constant B 0.131 0.028 0.001 0.029 0.062 0.069 0.285 1.264 Age # 7.50 years S.E. Wald Sig. B 0.035 0.052 0.001 0.007 0.086 0.042 0.051 0.113 0.000 0.591 0.257 0.000 0.475 0.105 0.000 0.000 0.012 0.055 0.001 0.005 0.135 0.022 0.215 1.436 13.864 0.289 1.282 19.711 0.511 2.634 31.369 125.167 Age > 7.50 years S.E. Wald Sig. 0.034 0.052 0.001 0.007 0.059 0.043 0.054 0.102 0.730 0.291 0.463 0.501 0.022 0.615 0.000 0.000 0.119 1.117 0.540 0.454 5.209 0.253 15.874 200.077 Notes: The initial firm population is divided into two, the median age being the breakeven point. Subpopulation of younger firms includes 33,531 and older firms 33,527 observations