Lymphatic Filariasis: Eradication Strategies & Global Health

advertisement

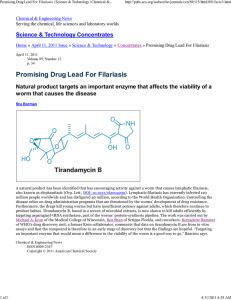

Running Head: Lymphatic Filariasis Promoting Health and Well-Being: Lymphatic Filariasis Natasha L Antonakis University of Wisconsin La Crosse HCA 780 10/22/2020 Lymphatic Filariasis 2 Abstract: The CDC and WHO have attempted to control the spread and combat the effects of communicable disease through mandatory reporting efforts, infection control recommendations, global programs, and published studies and goals for disease eradication. Lymphatic Filariasis affects over 100 million people in the tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world. As part of the UN Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, efforts to curtail transmission and morbidity from LF are underway. Five strategies to combat the disease are detailed through evaluation of studies qualified by location and the presence of filarial vectors. Collective results indicate that near eradication of Lymphatic Filariasis is possible through diligent efforts involving drug administration, hygiene, vector control, veterinary medicine, and effective oversight of implemented programs. Lymphatic Filariasis 3 Introduction Edemkong, Kopparapu, and Huang define communicable diseases as “illnesses caused by viruses or bacteria that people spread to one another through contact with contaminated surfaces, bodily fluids, blood products, insect bites, or through the air” (2020). Many forms of spread occur through oral feces route, sexual contact, insects, contaminated surfaces(fomites), skin to skin contact, or droplet contamination. An outbreak or epidemic occurs when and agent is present and able to be conveyed to susceptible hosts in large numbers. Epidemics and infectious disease have existed since the beginning of time. Charged with notable deaths, political unrest, and even the collapse of an empire, communicable disease has shaped the history of mankind. From early on, man has tried to understand disease; how it is transmitted and ways to combat its effects. As knowledge and technology evolve, so does the understanding of disease pathology and etiology. While it was always understood that diseases were contagious, knowledge of modes of transmission and susceptibility was lacking leading to failed efforts to control transmission. Most recognizable of the current focus on communicable disease are HIV/AIDS, Measles, Tuberculosis, Malaria, Hepatitis, West Nile Virus, Zika, and most recently COVID-19. Much research, testing, and planning has surrounded these diseases and the affected populations. As such, the UN Sustainable Development Goal number 3; By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases, is testament to the detriment communicable disease has on world populations. As of 2017, WHO through the Strategic and Technical Advisory Lymphatic Filariasis Group for Neglected Tropical Diseases updated the list of NTD to include 20 diseases/disease categories. Included are Buruli ulcer Chagas disease Dengue and Chikungunya Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease) Echinococcosis Foodborne trematodiases Human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) Leishmaniasis Leprosy (Hansen's disease) Lymphatic filariasis Mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis and other deep mycoses Onchocerciasis (river blindness) Rabies Scabies and other ectoparasites Schistosomiasis Soil-transmitted helminthiases Snakebite envenoming Taeniasis/Cysticercosis Trachoma Yaws (Endemic treponematoses) 4 Lymphatic Filariasis 5 These are the less spoken of communicable diseases and are prevalent in tropical and subtropical conditions in 149 countries. Those who live under adverse conditions such as poverty, poor sanitary conditions, and amongst plentiful vectors are the most affected. NTD has become a topic of concern as their impact on the economy, health, and overall quality of life of the affected population is better understood. As such, the United Nations has recognized the seriousness of these diseases and has put ending the epidemic of NTD on the list of Sustainable Development Goals to be realized by 2030. Lymphatic Filariasis is a parasitic communicable disease caused by 3 species of round worms: Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. The worms are spread through vector transmission by mosquito bites. The microfilaria, or microscopic worms are transmitted from the blood of an infected person to the mosquito and then to an uninfected host through the bite of that same mosquito. The microfilaria travel through the lymph system and are stored in the lymph nodes where they become adult worms. Effects of the parasite include lymphedema, swelling of the lymph system that may include swollen, cracked, and infected limbs and scrotum in men. The strain on the lymphatic system creates an environment where the body may struggle to fight off further sources of infection. Even after treatment for Lymphatic Filariasis, the damage to the lymphatic system remains and the affected individual must follow a strict limb care regimen to prevent further infections. While many affected individuals are asymptomatic, those that have visible symptoms struggle with disability, mental health issues from social stigma, and an overall decreased quality of life. The World Health Organization determined that Lymphatic Filariasis, a NTD, is an important public health concern and upon development of diagnostic tools and drugs for treatment, launched the Global Programme to Eliminate LF (GPELF) in 2000 and identified 5 Lymphatic Filariasis 6 strategies to combat NTD. With implementation of identified strategies beginning in the year 2000, we should be near total eradication of new cases of Lymphatic Filariasis by the year 2030. The five strategies recommended by GPELF are as follows: * Preventive chemotherapy of population at risk/infected Mass Drug Administration (MDA) * Intensified case-finding and management * Integrated vector control/management * Provision of safe water, sanitation, and hygiene * Veterinary public health. Detailed steps can be taken under each of these five categories to work towards control and eventual eradication of Lymphatic Filariasis. \Methods Google, Google Scholar, and the UW systems library were utilized to search the topics of Lymphatic Filariasis and communicable disease. Sources were chosen that indicated scientific study of LF with numeric findings, global program effectiveness, and evaluation of causes, treatments, and morbidity from the disease. Studies published from varied journals were utilized to avoid any type of bias. While some literature sources were reviews in and of themselves, the information provided was deemed pertinent and beneficial to the topic of combating Lymphatic Lymphatic Filariasis 7 Filariasis and was therefore included for review. Data was collected via survey, sampling, through procedure and medication trials and scientific testing methods. Information from WHO and the CDC supplemented study findings as confirmation of dissention to findings for this Literature Review. The information was organized by strategy and studies of the strategy were summarized by topic. When applicable, information obtained from the CDC and WHO supplemented reported findings. Scientific fact and human opinion and thought were obtained and recorded through the reviewed trials. As such, findings vary between simplified data and stated thoughts and ideas (as reported by study subjects) on the topics under each strategy. Body Mass Drug Administration The goal of MDA is to reduce the density of parasites circulating in the blood of infected persons and prevalence of infection in communities to levels where transmission is no longer sustainable by the mosquito vector (Gyapoung, et al., 2018). A qualitative study by Ahoulr et al.,aimed to determine community acceptance through participation and ingestion of choice drugs for elimination of LF; Ivermectin (IVM) in combination with Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) or Albendazole (ALB),and to gather information to promote intervention strategies in hotspot areas (Ahorlu et al., 2018). Findings suggest that there are multiple barriers to medication regimen compliance that span from personal to health system related. Residents were aware of the program and the treatment plan, but compliance varied (Ahorlu et al., 2018). Reasons for noncompliance given from respondents was as follows: Lymphatic Filariasis 8 Fear of side effects Patients thought they were not susceptible (those that were infected but did not have visible signs/symptoms) Personal dislike for medicine Distrust of/dishonest program facilitators Healthcare facility request for payment prior to medication dispensing Findings suggest that any program must be compatible with its intended recipients and environment for success. The reasons for noncompliance can be utilized to gear the program towards successful interruption of LF transmission in hotspot areas by customizing the approach towards the affected populations. Types of Medication, Dosage, and Effectiveness Treatment consisting of a single dose of a three-drug regimen of ivermectin plus diethylcarbamazine plus albendazole was tested against a single dose of a two-drug regimen of diethylcarbamazine plus albendazole (King et al., 2018). The testing involved a randomized controlled trial from villages in New Guinea of patients who had not received any PF treatment prior to the study. Results of the study found that a single dose of a three-drug regimen of ivermectin plus diethylcarbamazine plus albendazole was more effective in clearing W. bancrofti microfilariae from the blood than a single dose of a two-drug regimen of diethylcarbamazine plus Lymphatic Filariasis 9 albendazole(King et al., 2018). The conclusion was that both drug regimens actively reduce circulating filarial antigen levels with the triple drug treatment also killing adult worms making it a more effective treatment with less probable disease transmission. Therefore, the three-drug regimen of ivermectin, diethylcarbamazine, and albendazole was deemed by the authors as a potential effective treatment for the elimination of lymphatic filariasis. WHO reports “a single dose of diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC) has the same long-term (1 year) effect in decreasing levels of microfilaraemia as the formerly recommended 12-day regimen of DEC. More importantly, the use of single doses of two drugs administered together (optimally albendazole with DEC or ivermectin) is 99% effective in removing microfilariae from the blood for a full year after treatment” (WHO, 2016). This does not contradict study findings nor does it correlate with the finding that the triple drug treatment is most effective. Provision of Safe Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Stocks, Freeman, and Addiss performed a systemic review and meta-analysis of studies of the effects of hygiene -based lymphedema management in Lymphatic Filariasis endemic areas. LF creates a condition of swollen limbs that are prone to cracking and infections. Acute bacterial dermatolymphangioadenitis (ADLA), inflammation of skin, tissue, and lymphatics, has been demonstrated in several case studies of Lymphatic Filariasis. Per the authors, ADLA further erodes lymphatic function, stimulates fibrosis, and increases the risk of additional ADLA episodes which complicate LF (2015). Lymphedema management programs in the reviewed studies all included a hygiene element such as washing limbs with soap and water and combinations of other various treatments Lymphatic Filariasis 10 such as lymph fluid drainage, compression bandages, body movement exercises, foot/leg creams, and education on limb care. Direct findings of the study indicate that “the proportion of lymphedema patients experiencing at least one ADLA episode in a given time period decreased from 49.6% at baseline to 16.2% after implementation of hygiene based lymphedema management (Stocks, Freeman, and Addiss, 2015). Stocks, Freeman, and Addiss state the evidence strongly supports the effectiveness of hygiene-based lymphedema management in LF-endemic areas in controlling the morbidity and disability associated with LF but does not affect the spread of the disease (2015). WHO recommends rigorous hygiene of the affected areas in combination with a regimen to promote lymph flow and limit infection, as bacterial and fungal infections promote the pathology of LF. This correlates with study findings (WHO, 2016). Intensified Case-Finding and Management Global elimination of lymphatic filariasis is achieved through treatment of at-risk populations with annual or bi-annual mass drug administration campaigns. To ensure effectiveness of MDA, the proper population coverage must be achieved. To do this, surveys must accurately depict the affected populations and medication administration must be properly documented. Maroto-Camino et al., evaluated MDA programs for effectiveness. The World Health Organization has established that to eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis as a public health problem, a minimum of five consecutive annual MDA rounds with effective Lymphatic Filariasis 11 coverage; administration of medication to at least 65% of the total population, must be administered. WHO has requested that endemic countries conduct household surveys to validate the reported MDA coverage rate and support action where microfilaremia persists despite reports of achieved coverage targets (Maroto-Camino et al., 2019). With Suboptimal MDA coverage persistent parasite transmission is imminent leading to infection, disease and disability, and the need for even more drug treatments substantially raising the cost of treatment efforts. To verify effectiveness of MDA coverage, WHO recommends verification of the campaign’s administrative records using household cluster surveys at least once every 5-years (Maroto-Camino et al., 2019). The authors evaluated surveys with suboptimal coverage for QA purposes. These evaluations addressed reasons for failure of the MDA, residents not taking the medication, places where the medication was received, information sources, and knowledge about diseases prevented by the MDA (Maroto-Camino et al., 2019).Their results showed that administrative records over-estimated treatment area coverage and did not detect implementation and problems due to errors in numerators and denominators, incorrect reporting, and/or incorrect data (MarotoCamino et al., 2019). Integrated Vector Control/Management Lymphatic Filariasis 12 Vector control is thought to be a valuable secondary measure to prevent the spread of Lymphatic Filariasis. There are several species of mosquito that can carry and transmit the filarial nematodes involved in LF. Lymphatic filariasis is transmitted by many species of mosquitoes in four principal genera—Anopheles, Culex, Aedes and Mansonia (WHO,2020). Each species has a different rate of parasite transmission. For filariasis transmission to be interrupted, vector density or microfilaria intensity needs to be lowered to ensures no new infection occurs (Bockarie, Pedersen, White, & Michael, 2009). Two types of eradication thresholds are also most likely to exist for LF; one related to the infection transmission process (biting humans) from the vectors and the other to worm infection levels in the human host. The two thresholds exist wherein the level of biting is too low to facilitate transmission and when the level of worms in the human body is too low to allow for transmission to the vector(mosquito). “Vector control is particularly attractive for LF because transmission of the parasite is inefficient. There is no multiplication of the parasite in the mosquito vector and only continuous exposure to bites of many infected mosquitoes maintains the infection in humans” (Bockarie, Pedersen, White, & Michael, 2009, p. 474). Measures taken to prevent or eliminate the breeding of mosquitoes in their natural or human-made habitats included closing of wells and eliminating unnecessary bodies of water. Biological control methods included the release of natural predators such as certain species of fish in suitable habitats. Application of pesticides and chemical larvicides can also be utilized. After five years of studied vector control activities, the reported vector density was reduced by 90% (Bockarie, Pedersen, White, & Michael, 2009). Lymphatic Filariasis 13 Successful vector control requires adequate resources and well-trained personnel with appropriate oversight. The reviewed results show that vector control could serve as a major tool in combination with MDA for achieving LF elimination in endemic areas. Veterinary Public Health The role of animals in the spread of LF is unclear. Humans are considered the main definitive host of filariasis, but there are several animals that can transmit filarial infections Mulyaningsih et al., 2019).There have been studies conducted that identify the species Brugia Malayi, one of the three parasites that cause Lymphatic Filariasis, as present in dogs and other animals, the notion that the animals are able to spread the parasite to humans is disputed. Two studies, one on canine filarial infections in India and another on Brugia Malayi in Indonesia agree that LF from Brugia Malayi is zoonotic, meaning it can be spread from animals to humans. The articles relay that cats and dogs and monkeys have been determined to host B Malayi, respectively. Findings by Ravindran et al., did not find evidence to support dog to human transmission in the current study (2014). With the above detailed information from the literature review, is total eradication of Lymphatic Filariasis a possibility and is the 10-year time frame of eradication by the year 2030 feasible? Discussion Lymphatic Filariasis 14 A successful eradication campaign can be realized based on the scientific findings from the literature reviewed. The gathered research data and information clearly supports the means to prevent further spread of microfilaria through vector transmission and to minimize further complications in those who currently have manifest symptoms. By utilizing the recommended treatment regimen of a single dose of a three-drug regimen of ivermectin plus diethylcarbamazine plus albendazole as part of a LF reduction campaign with high oversight and accurate data maintenance regarding population coverage, the levels of circulating microfilarial antigens and live worms can be reduced, the first threshold needed for transmission, to a nontransmissible level in hosts. Vector management in the way of pesticide applications and biological elimination methods, and monitoring breeding grounds has proven to reduce the vector population by 90% and therefore greatly reducing the vector to human bites, the second threshold needed for transmission. Barriers to prevention exist in the human element to the treatment processes. Resistance and non-compliance on behalf of the affected population and human error, negligence, and lack of enthusiasm of the public health and community members tasked with record keeping and drug administration efforts will actively work against the eradication campaign. Successful efforts will include an education portion to the campaign, addressing the fears and concerns of the affected population. Benefits of total eradication must be thoroughly established and discussed through the education and downfalls of non-compliance and associated disability and mortality clearly outlined. Conscientiousness regarding medication administration, ingestion, and overall compliance must be made mandatory, but first must be understood by the Lymphatic Filariasis 15 population. The MDA efforts must be subsidized so that all treatment, regardless of ability to pay, is maximized. A campaign of trust needs to be fostered between the medical providers, public health, and community health workers and the treatment population. This must include accurate record keeping and working with integrity towards LF eradication. The promise of and inclusion of follow-up care including teaching and provision of hygiene techniques and supplies to prevent further complication from irreversible disease effects as a philanthropic effort once drug administration has been completed, will continue to foster trust between the two groups. In addition to these efforts, generalized sanitation measures and education must be addressed within the communities. This includes the importance of proper veterinary care from farm and domesticated animals, and the effects that the state of the environment can have on the human population regarding the spread of illness and disease. If the above measures are taken, maintained, and reevaluated annually for effectiveness, it is my belief that the goal of total eradication by the year 2030 can be realized. Conclusion The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal #3; good health and well-being, seeks to ensure health for all regardless of age, ability, or status. This goal addresses all major health priorities, the conditions, resources, and knowledge. Specific to this focus is strengthening each countries ability to identify, reduce, and manage health risk. Lymphatic Filariasis 16 NTD, neglected tropical diseases effect not only physical well-being but also the mental health of the affected and their caregivers. Addressing the causes and potential treatments and eradication efforts of the diseases are essential to maintain health across the world. The UN and WHO address these issues and have increased efforts through global programs to eliminate communicable disease. Neglected tropical diseases affect the poorest of nations with the weakest populations. This only intensifies the spread of the diseases and inhibits efforts to control them. Following recommended guidelines through global programs to eliminate specific NTD, is a step towards providing health and well-being for inhabitants across the globe. Eradication of Lymphatic Filariasis is possible with collaboration of the global health initiatives, community workers, and the affected populations. Lymphatic Filariasis 17 References Ahorlu, C. S., Koka, E., Adu-Amankwah, S., Otchere, J., & Souza, D. K. (2018). Community perspectives on persistent transmission of lymphatic filariasis in three hotspot districts in Ghana after 15 rounds of mass drug administration: A qualitative assessment. BMC Public Health, 18(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5157-7 Bockarie, M. J., Pedersen, E. M., White, G. B., & Michael, E. (2009). Role of Vector Control in the Global Program to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis. Annual Review of Entomology, 54(1), 469-487. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.54.110807.090626 Edemekong, P., Kopparapu, A. K., & Huang, B. (2020, September 10). Epidemiology Of Prevention of Communicable Diseases. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470303/ Gyapong, J. O., Owusu, I. O., Vroom, F. B., Mensah, E. O., & Gyapong, M. (2018). Elimination of lymphatic filariasis: Current perspectives on mass drug administration. Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine, Volume 9, 25-33. doi:10.2147/rrtm. s125204 King, C. L., Suamani, J., Sanuku, N., Cheng, Y., Satofan, S., Mancuso, B., . . . Kazura, J. W. (2018). A Trial of a Triple-Drug Treatment for Lymphatic Filariasis. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(19), 1801-1810. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1706854 Lymphatic filariasis. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lymphatic-filariasis Lymphatic Filariasis 18 Maroto-Camino, C., Hernandez-Pastor, P., Awaca, N., Safari, L., Hemingway, J., Massangaie, M., . . . Valadez, J. J. (2019). Improved assessment of mass drug administration and health district management performance to eliminate lymphatic filariasis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 13(7). doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007337 Mulyaningsih, B., Umniyati, S. R., Hadisusanto, S., & Edyansyah, E. (2019). Study on vector mosquito of zoonotic Brugia malayi in Musi Rawas, South Sumatera, Indonesia. Veterinary world, 12(11), 1729–1734. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2019.1729-1734 Neglected tropical diseases. (2020, October 19). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/en/ Reghu Ravindran, Sincy Varghese, Suresh N. Nair, Vimalkumar M. Balan, Bindu Lakshmanan, Riyas M. Ashruf, Swaroop S. Kumar, Ajith Kumar K. Gopalan, Archana S. Nair, Aparna Malayil, Leena Chandrasekhar, Sanis Juliet, Devada Kopparambil, Rajendran Ramachandran, Regu Kunjupillai, Showkath Ali M. Kakada, "Canine Filarial Infections in a Human Brugia malayi Endemic Area of India", BioMed Research International, vol. 2014, Article ID 630160, 9 pages, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/630160 Stocks, M. E., Freeman, M. C., & Addiss, D. G. (2015). The Effect of Hygiene-Based Lymphatic Filariasis Lymphedema Management in Lymphatic Filariasis-Endemic Areas: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(10). doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004171 Treatment and prevention. (2016, July 04). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/lymphatic_filariasis/epidemiology/treatment_prevention/en/ 19