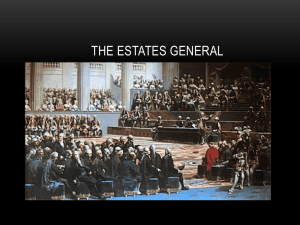

THE ORIGINS OF REVOLUTION PowerPoint 1 A LONG TIME COMING In the second half of the 18th Century, the very roots of the long-established social, political and economic foundations of French society – based on privilege, hierarchy and tradition – were being challenged. The French king, Louis XVI, faced with pressure from elite groups in his kingdom, recognised the need for reform, which in his assessment was limited to the issue of taxation. This is one of history’s great understatements. FEUDALISM France’s social, economic and political structure was still built around the principles of feudalism. Feudalism was the dominant social system in medieval Europe, in which the nobility held lands from the Crown in exchange for military service. Vassals were, in turn, tenants of the nobles. Peasants were obliged to live on their lord's land and give him homage, labour, and a share of the produce, in exchange for military protection. THE ANCIEN RÉGIME Largely a rural society In 1780, France’s population was approximately 28 million. If we define an urban community as one with more than 2000 people, only 20% of France’s population lived in an urban centre. Paris, a walled city, the largest with ~700,000 people. Lyon, Marseille & Bordeaux the other significant cities. Over 38,000 rural communities with an average population of approximately 600. Regardless of where the residents of France lived, they were still divided up into the three ‘estates’ – a division still lingering from the old medieval days when society could be separated into: 1. 2. 3. Those who prayed Those who fought Those who worked Note: The King was not part of an estate, but sat atop the pyramid as he was ‘elected by God’. Clergy Nobility Others First Estate Second Estate Third Estate THE THIRD ESTATE THOSE WHO WORKED Comprising roughly 98% of the national population, the Third Estate was populated by those who were not members of the church or the nobility. Notable subgroups of the rural Third Estate include: Free peasants, who owned their land. Could rent out land and equipment, and were despised by the lowerclass peasants who, in reality, aspire to join the ranks of the free peasants. Serfs and peasants (owned or leased some land). Tiny sections. Many people who passed through France remarked on the backwards nature of French agriculture, in comparison to the larger-scale operations throughout the rest of Europe. Wage labourers (landless peasants). Price inflation was not matched by wage increases – led many to a life of crime to sustain their families. THE THIRD ESTATE THOSE WHO WORKED The (relatively) urban corollary of the rural peasantry, living in France’s towns and cities include: The unskilled labourer. The best job they could hope for was that of a servant in the homes of the urban elite. They lived either on the street or in terrible housing. The skilled labourer. The medieval guild system, in all of its restrictive glory, was still in full effect in the 18th Century. Apprentice Journeyman Masters In contrast with the progressive idea of free trade, the guild system was a constant source of frustration for those not directly profiting from it. It is from the pool of these urban workers that the (in)famous Sans Culottes will appear later in our story. THE THIRD ESTATE THOSE WHO WORKED Above the ranks of the skilled workers, we have the secure urban elite, known as the bourgeoisie. In strict Marxist terms, this means the ‘owners of the means of production’. In a broader sense, the bourgeoisie included the middle-class professionals, including doctors, lawyers, and men of letters. Collectively, one of the fastest growing groups in 18th Century France and now held a large portion of the nation’s wealth. The bourgeoisie would usually not direct their increasing wealth back into the trades that had enriched them. Rather, they would look to buy their way into the nobility, by one of two means: 1. 2. The purchase of land The purchase of venal office An office sold by the state to raise money without having to raise taxes. On the eve of the Revolution, nearly every one of the 70,000 government offices was venal – many of them an empty title that carried with it certain privileges. The most prominent privilege was ennoblement and its wonderful tax exemptions. By the late 18th Century, approximately one billion livre was tied up in venal offices. THE SECOND ESTATE THOSE WHO FOUGHT In the late 18th Century, the population of the nobility was somewhere between 120,000 and 400,000 – approximately 1% of the national population. This 1% owned between 1⁄4 and 1⁄3 of all the land in France and often held feudal privileges over the rest. Feudal privileges include the right to collect certain taxes, or the right to force tenants to lease your equipment to work the land. It’s important to know that the nobility was not one homogenous class: The sword (old) nobility The robe (new) nobility The super nobility (from the sword class, but still had immense wealth). This group lived with the king at Versailles and held many prominent positions in the government and clergy. THE FIRST ESTATE THOSE WHO PRAYED In 18th Century France there were approximately 130,000 members of the French clergy. Collectively, the church owned ~10% of all the land in France. The clergy was basically a microcosm of the kingdom at large. In 1516, the pope allowed the King of France the right to appoint all the bishops & abbots of the French church. These roles that carried huge salaries, the right to collect tithes, etc. went to the men of the nobility. The vast majority of the 130,000 clergy were parish priests, often recruited from the lower rungs of the third estate. There was a huge gulf between the high and low rungs of the church, which will become very important when the estates general is called in 1789. The lowly parish priests will finally have the opportunity to speak against the parasitic and greedy bishops and the wildly unequal distribution of church wealth. THE KING OF FRANCE AND THE BOURBON DYNASTY SETTING THE SCENE LOUIS XIV Ruling for 72 years, Louis XIV oversaw a golden age of literature and art, claimed nearby territories, and established France as the most dominant European nation. For this, he is known to history as the Sun King. However, in his later years, he: Engaged in several lengthy wars Expelled protestants from France Brain Drain Spent extravagantly 1638-1715 SETTING THE SCENE VERSAILLES Louis XIV faced a revolt, known as the Fronde, from provincial nobles. He converted a hunting lodge on the outskirts of Paris into the Palace of Versailles for two reasons: 1. To project an image of power, representing the strength of the French kingdom. 2. To take all those pesky nobles away from the provinces, where they had been causing trouble, to jostle for position next to his throne. Cutting them off from their bases of support and plying them with lavish gifts, Louis XIV domesticated the French aristocracy. SETTING THE SCENE LOUIS XV 1710-1774 Becoming King in 1715, at the age of 5, Louis XIV’s great great grandson, Louis XV, is best known for building on the late failures of his grandfather and further contributing to the decline and eventual fall of the royal family and Ancien Régime. • Initially well liked by the people; nicknamed ‘The well beloved’. • Sided with Austria, traditionally France’s enemy, in the Seven Years War against Britain, the result of which was not great for the King’s popularity, or the prestige of France. • Poor harvests and continued spending depleted France’s economic reserves. • Louis XV died in 1774, leaving a legacy of diplomatic, military and economic malaise, if not regression. SETTING THE SCENE THE SEVEN YEARS’ WAR France was involved in many wars throughout the 18th Century, however we’re only going to pay attention to the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). Sometimes referred to as World War Zero due to its scale, the Seven Years’ War involved every great European power and spanned five continents. Began with the French & Indian War (1754-1763), but European territorial ambitions at home dragged everyone into conflict. In the end, France acknowledged the loss of all its territory on the North American mainland and the Indian subcontinent, and Britain emerged as the dominant European colonial power. THE FINAL KING OF FRANCE LOUIS XVI 1754-1793 The King of France during the American Revolutionary War and the beginning of the French Revolution, Louis XVI is often characterised as a shy, immature, ineffectual leader, who cared more about his hobbies and indulging his wife’s extravagant tastes than he did ruling. He was, however, bright, and athletic during his youth, and genuinely wanted to tackle the huge task of reforming the kingdom. • • Rule beset by enormous, inherited debts and rising resentment towards the monarchy. Successfully supported American colonies’ fight for independence in the American Revolution. • A political victory, but achieved via international loans – drove France near bankruptcy. SETTING THE SCENE THE AMERICAN DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE On 4 July 1776, delegates from the Thirteen British Colonies in North America approved the Declaration of Independence in which they outlined the reasons for their renunciation of British sovereignty, providing the moral rationale for their decision and a list of grievances against King George III. In a clear break from the past, the colonists declared ‘that all men are created equal’ and were ‘endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights’. They declared these rights to be ‘Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’. In defiance of the divine right of kings, the American colonists argued that governments derive their powers from ‘the consent of the governed’, who have the right to abolish them when ‘any form of government becomes destructive’. THE FINAL QUEEN OF FRANCE MARIE ANTOINETTE The wife of King Louis XVI. Archduchess of Austria – married to Louis in 1770, aged 15 and 16, respectively. Initially popular, however this began to wane. Seen as overly profligate, promiscuous, and of hiding sympathies for France’s enemies. Nicknamed ‘Madame Deficit’ because of her lavish spending in the face of mounting national debt. Famous for (not) saying ‘Let them eat cake’. 1755-1793