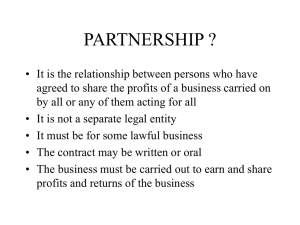

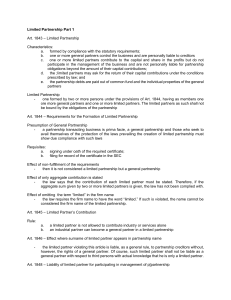

Partnership Law: Definition, Characteristics, and Distinctions

advertisement