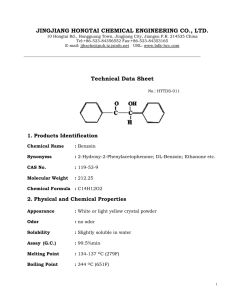

12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer The Jet Lawyer 300 LEVEL NOTES, 300 LEVEL 1ST SEMESTER COMMERCIAL LAW 1 NOVEMBER 22, 2015 | OLANREWAJU OLAMIDE | LEAVE A COMMENT Definition of Sales of Goods By the provision of S.1(1) of the Sales of Goods Act, a contract of sale is one whereby a seller transfers or agrees to transfer the property in goods to the buyer for a money consideration called the price. A contract of sale could be absolute or conditional; S.1 (2) SOGA. A contract of sale can be an outright sale or an agreement to sell. It is an outright sale if by the time the contract is made; the goods are transferred from the seller to the buyer. It is an agreement to sell if by the time the contract is made, the goods are to be transferred at a future date or upon the fulfillment of some conditions; S.1 (3) SOGA. An agreement to sell would become a sale when the time for delivery elapses or the conditions are fulfilled; S.1 (4). http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 1/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer Formation of a Contract of Sales By virtue of the provisions of S.3 of the Sales of Goods Act, no formality is required for the formation of a contract of sale. It could be written or oral or a mixture of both. It could also be concluded by the conduct of the parties to the contract. It is however provided that this provision shall not affect the law relating to a corporation. Therefore, although a company has the powers of a natural person, if its memorandum stipulates that its contracts of sale should be in a particular format, they must be in that format; S.38 (1) Companies and Allied Matters Act. Essentials of a Contract of Sale The following are essential requirements for the formation of contract of sale of goods: 1. Two Parties: In a contract for sale of goods, there must be two parties present; the buyer and the seller. The parties do not necessarily have to be two single individuals; it could be two corporations with one as the buyer and the other as the seller. 2. Offer and Acceptance: Another important ingredient for a contract of sale is offer and acceptance. The offer most likely comes from the buyer and the acceptance comes from the seller. However, in some situations, this role may be reversed. 3. Consent: Another important ingredient is the consent of the parties. A contract of sale in which one of the parties is under duress would not be valid. The parties have to be aware of what they are doing and they should consent to it. 4. Capacity: By the provisions of S.2 SOGA, capacity to contract in sales of goods is governed by the general law relating to capacity to contract. However, where necessaries are sold to an infant, a drunkard or a person with mental incapacity, such persons must pay a reasonable price. Necessaries are further defined as goods that are important and suitable for the life of such persons that lack capacity. 5. Price: The price in a contract of sale of goods serves as the consideration. The price is usually in monetary terms. It could also be in monetary terms and in goods. There are different ways of fixing the price. The price could be fixed by the provision of the contract, at the time of dealing or in the manner agreed to by the parties; S.8 (1) SOGA. In a situation in which a price was not fixed for the purchase of the goods, a reasonable price should be fixed. The reasonableness of a price depends on the individual circumstances of each case; S.8 (2) SOGA. http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 2/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer 6. Time: By the provisions of S.10 SOGA it is stated that time for payment isn’t considered of the essence except it is stipulated by the terms of the contract. This provision isn’t clear about the time of delivery. But by the provisions of S.29(2) it is stated that if no time for delivery is provided, the goods should be delivered within a reasonable time. This goes to show that although time of payment is not of the essence, the time of delivery is important. Thus in the case of Amadi Thomas vs Thomas Aplin & Co Ltd (1972) 1 All NLR @409 the goods were to be delivered at a particular time but the seller didn’t comply with the time stipulated. The court ruled that the time of delivery is of the essence. Thus the failure to stick to the time provided by the contract was a breach of the contract of sale. 7. Goods: By the provisions of S.62 (1) of the Sales of Goods Act, goods have been defined as chattel personal other than money. However it should be noted that land is not included under the ambit of sales of goods. Under the Act, goods have been broadly classified into four namely specific goods, future goods, unascertained goods, existing goods. Specific goods are goods that have been clearly identified and agreed upon at the time of the contract of sale. See S.18 SOGA. Future goods are goods that would be manufactured by the seller after the conclusion of the contract of sale. They are not in the possession of the seller at the time of the contract. They are delivered to the buyer at a future date; S.5 (1) SOGA. Unascertained goods are those that are not yet specified. They are usually sold by general descriptive terms for that class of goods. For example, a contract for 50 crates of eggs that haven’t been seen by the buyer is one that involves unascertained goods. The 50 crates of eggs in this scenario are unascertained. Existing goods are those that the seller already possesses at the time of the contract of sale; S.5 (1) SOGA. In the case of existing goods, property in the goods passes once the buyer takes delivery of such goods. Conditions and Warranties (S.11 SOGA) Conditions are those terms of a contract of sale which if breached, would lead to the repudiation of the contract. Warranties, on the other hand, are those terms the breach of which would only give rise to the payment of damages and not the repudiation of the contract; S.11 (1) (b). To determine if a statement is a condition or warranty attention should be paid to the construction of the contract. There are some instances in which the breach of a condition could be interpreted as a breach of warranty. One of such instances is when the buyer decides to waive the condition. The buyer http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 3/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer could also regard the breach of condition as a breach of warranty; S.11 (1) (a) SOGA. Also, if the goods have been accepted by the buyer in whole or in part, or property has passed to the buyer, the breach of a condition would have to be treated as a warranty; S.11 (1) (c) SOGA. Generally, conditions are fundamental terms while warranties are minor terms in the contract of sale. Warranties and Mere Representation A representation is a statement made by the seller in a contract of sale usually as a means to entice the buyer. A representation is not usually regarded as a term of a contract. However in some situations, if the representation was made by the seller to the buyer and the buyer depended on the representation due to the fact that he thinks the seller has more knowledge in that regard, it could be treated as a warranty by the court. Whether a statement is a mere representation or a warranty depends on the intention of the parties, their conduct and other surrounding circumstances. See: Hopkins vs Tanquery (1864) 15 QB 611; Couchman vs Hill (1947) KB 554. Ownership and Passage of Property (S.12 SOGA) This is encapsulated in the Latin maxim: Nemo dat quod non habet. This translates to mean “you can’t give what you don’t have”. Thus, S.12 SOGA provides that before ownership can be transferred, the following has to be met: 1. If it is a sale, a condition that seller has the right to sell and if it is an agreement to sell, the seller would have the right to sell at the time the property in the goods will pass 12 (1). 2. There must be a warranty of quiet enjoyment and non-interference; 12 (2). 3. A warranty that the goods are free from third party charges and encumbrances; 12 (3). In the case of Akoshile vs. Ogidan 1950 19 NLR 87, the defendant bought a stolen car from a third party. He subsequently sold the car to the plaintiff. When the third party was arrested, the car was collected from the plaintiff by the police. The plaintiff subsequently sued for the price he paid to the defendant. The court held that the sale of the car to the plaintiff by the defendant was in breach of the condition S.12 (1). This was due to the fact that the defendant didn’t have a title to the goods since they were stolen. Thus, he could not transfer same. Exceptions to the Rule http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 4/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer This rule lends itself to some exceptions. They are: 1. Where there is a sale of property by an agent. By the provisions of 21(1) title can be passed by a person who is not the owner if he sells the goods on the permission of the true owner; Imam vs. ABU 1970 NNLR @p39. 2. Where the principle of estoppel applies: This could come to play in situations in which the true owner by conduct or words implies that the seller has ownership of the property. It could also arise due to the negligence of the owner which gives the seller the authority to sell. This could be seen by the closing part of S.21(1) where it said that sale by persons not the owner would be valid if the owner has by his conduct been precluded from denying the seller’s authority to sell. 3. Sale By a Mercantile Agent Under The Factors Act: It is stated by the provisions of S.21 (2) (a) SOGA that this rule doesn’t apply to goods sold under the provisions of the Factors Act. The factors act deals with the regulation of sale of goods by a mercantile agent. A mercantile agent has been defined by S.1 (1) of the Factors Act as a person whose normal business it is to receive goods as an agent for the purpose of the sale of such goods. Thus a person who decides to help his friend sell some goods to a third party cannot be regarded as a mercantile agent. This is due to the fact that being an agent is not his normal business. For this exception to apply, these conditions have to be met: The seller is a mercantile agent who is in possession of the goods and has obtained title: According to provisions of S.2 (1) of the Factors Act, a mercantile agent in the possession of goods or of the document of title to goods can sell those goods if they were bought in good faith. The possession is with the consent of the owner: According to the provisions of S.2 (1) of the Factors Act, in order for the sale to be valid the mercantile agent must have gotten possession of it with the consent of the owner. In the case of Pearson vs. Rose and Young Ltd (1950) 2 All ER 1027, the plaintiff delivered his car to a mercantile agent in order to just get offers, not to sell the car. The agent intended to sell the car as soon as possible and to embezzle the funds. Thus, he tricked the plaintiff into leaving the registration book with him. While the owner/plaintiff was away, the agent sold the car to a third party. In court, it was held that although the agent was in possession of the car and the registration book, the possession of the registration book was without the owner’s consent. Thus, he http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 5/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer couldn’t validly sell the car since a car can’t be sold without its registration book. The property was moved willingly The property must have been purchased on value and in good faith: This means the goods purchased must have been done honestly. If the value of the goods being sold were so low as to warrant suspicion as to the authenticity of the contract of sale, it could mean that the buyer’s case for good faith would be affected. 4. Sale in Market Overt: By the provisions of S.22 (1) SOGA, goods that are bought in a market overt in good faith are also exempted from the application of this rule. A market overt has been defined by Jervis J in Lee vs. Bayes 1856 18 CB 599 at p. 601 as an open, public and legally constituted market. A mallet overt is one that is usually open during the hours of sunrise and sunset. For this rule to apply, the goods have to be sold in the market within the hours of operation of the market. 5. Sale under Voidable Title: By the provisions of S.23 of the Sale of Goods Act, where a seller has a voidable title to the goods in his possession and he sells them before his title becomes void, the buyer has gotten a valid title to the goods purchased if the goods are bought in good faith. Thus, in the case of Lewis vs Averay a rogue misrepresented himself as a popular actor to the plaintiff in order to purchase a car from him. The car was purchased with a cheque which later bounced. The rogue sold the car to the defendant who bought it in good faith. After the fraud was discovered, the plaintiff sued the defendant for the car. it was held that the title which the rogue possessed after duping the plaintiff was voidable. Since the car was bought in good faith by the defendant from a person who had a voidable title, he had acquired a valid title. 6. Sale Under Special Powers: According to the provisions of S.21 (2) (b) SOGA, the validity of a contract of sale under common law power, statutory power and judgement of a court would be exempt from the provision of this rule. 7. Seller In Possession: According to the provisions of S.25(1) of SOGA, if a seller having sold the goods in question but he still has them in his possession and the goods are bought in good faith by another party who is ignorant of the initial sale, such party has acquired a valid title. 8. Buyer In Possession: By the provisions of S.25(2) of SOGA, if a person who has bought or agreed to buy some goods is in possession of the goods or documents of title, he can transfer http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 6/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer the same to another buyer who buys in good faith and the title would be considered valid. Sale of Goods by Description By the provisions of S.13 of the SOGA, where there is a sale of goods by description, there is an implied condition that the goods sold would fit the description that has been provided by the seller. In the case of Varley vs Whipp 1900 1 QB 513, the plaintiff sold a reaping machine to the defendant. The machine was described to be about a year old and used to cut about 50 to 60 acres. On getting the machine, it was discovered to be very old and the defendant returned it. The plaintiff sued for the contract price. The court held that the defendant could reject the goods since they didn’t fit the description provided and were a breach of condition as provided by S.13 of the SOGA. Quality of Fitness for Purpose and Merchantable Quality S.14 SOGA By the provisions of S.14(1) of the SOGA, there is an implied condition that the goods bought are fit for a purpose if the buyer discloses such purpose to the seller and relies on the seller’s knowledge in purchasing the goods. By the provisions of S.14(2) of the SOGA, where goods are bought by description from a seller who deals in goods of such description, there is an implied condition that such goods should be of merchantable quality. However, if the buyer has examined the goods this provision would not apply. Sale by Sample S.15 SOGA A contract of sale is a sale by sample where there is a term either express or implied in the contract that states it as such; S.15(1) SOGA. In a contract of sale by sample, there is an implied condition that the bulk of the goods would correspond to the sample in quality; S.15 (2) (a). There is also an implied condition that the buyer would have a reasonable opportunity of comparing the bulk and the sample; S.15 (2) (b). There is another implied condition that the goods are free from defects rendering it unmerchantable if the defects are such as cannot be http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 7/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer discovered on examination of the sample; S.15(2)(c) SOGA. Transfer of Property This is the moment at which it would be believed by the court that the property in the goods has passed from buyer to seller. The application of the rule is different in the instance of ascertained goods and unascertained goods. Specific or Ascertained Goods In the case of ascertained goods, it is provided by S.17 (1) that the property in the goods will be transferred to the buyer at the time in which it was agreed t by the parties. In order to pin point the intention of the parties as to when the property in the goods should be passed, S.17 (2) provides that regard shall be had to the contract, the conduct of the parties and the circumstances of the particular case. There are also additional rules provided for ascertaining the intention of the parties. The first rule as provided in S.18 rule 1 is that when there is an unconditional contract for selling specific goods that are in a deliverable state, the property in the goods will be passed when the contract is agreed upon. This is regardless of whether or not the date for payment or delivery has been postponed. The second rule under S.18 is that in the case of goods that are not in a deliverable state and the seller has to do something to the goods to make them deliverable, property in the goods passes when such things are done and the buyer is notified of such. In the case of Underwood ltd vs Burgh Castle, the plaintiffs intended to sell a condensing machine to the defendants. The machine weighed 30 tons and was bolted to the ground. Thus the machine had to be dismantled and transferred to the defendant. After dismantling the machine, as it was about being loaded on the railway, it got spoilt. The court held that property in the goods had not yet passed to the defendant since the goods were not yet in a complete deliverable state when the machine got spoilt. The third rule under S.18 is that when the goods are in a deliverable state but the seller has to weigh, measure, test or do some other thing to the goods in order to ascertain the price, property in the goods passes when such thing is done and the buyer is notified. The fourth rule provides that where the goods are delivered on a “sale or return” term or any other such term, the property passes when the buyer when he signified the acceptance of the goods or he does an act that adopts the transaction. http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 8/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer In a situation in which the buyer doesn’t signify any acceptance, the property passes when the date specified for rejection is elapsed. If no date is given, the goods will pass after a reasonable time. The determination of a reasonable time is a question of fact. See: Bull vs Smith Car Sale 1962 2 All ER Unascertained Goods By the provision of S.18 rule 5(1) in the case of unascertained goods, the property passes to the buyer when they have been unconditionally appropriated for such contract wither by the seller with the consent of the buyer or by the buyer with the assent of the seller. The assent could be given before or after the appropriation of the goods. Unconditional appropriation of goods to a contract means that the goods have been set apart from the bulk of unascertained goods and they would be used for that particular contract without modification. Also, if the goods are transferred by the seller to a third party for delivery to the buyer, the goods will be considered unconditionally appropriated to the contract S.18 rule5 (2) SOGA. TRANSFER OF RISK By the provisions of S.20 of the SOGA, risk in the goods passes from buyer to seller when the property in the goods are passed. This is encapsulated in the maxim “res perit domino“. In the case of Wardar’s Import and Export Ltd vs W.Norwood & Sons (1968) 2 WLR 1440, X had 1500 cartons of frozen kidneys in Y’s warehouse. He sold 600 cartons to Z and gave him a delivery note addressed to Y. When Z’s carrier arrived at the warehouse, he saw that the 600 cartons were already out on the pavement. Y accepted the delivery note from the carrier. At 8 am, loading started, however, the carrier didn’t turn on the refrigerator in his van till 10 am by which time the cartons on the pavement were dripping. Loading was concluded at 12 pm and the carrier signed a receipt stating that he had received the goods in soft condition. On delivery to Z, it was found out that the goods were of unmerchantable quality. and thus Z refused to pay. In court it was held that property in the goods passed when Y, a third party, acknowledged that the goods were for Z by accepting the delivery note. Thus, since property had already passed to the buyer when the damage to the goods occured, the risk would have to be borne by the buyer. http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 9/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer Exceptions To The Rule Where there is a contrary agreement between the parties, the agreement binds them;s.20 If delay is caused by either of the parties, the party responsible for the delay would bear the risk;S.20. For goods that are sent by sea, the right passes if the carrier successfully delivers them to the buyer. However, the seller should inform the buyer of the need to insure the goods. If the buyer refuses to insure the goods, the risk passes to the buyer; 32 SOGA. Where the seller agrees to deliver the goods at a place other than the agreed place at the instance of the buyer, the buyer would bear the risk of deterioration in the course of transit; S.33 SOGA. Mistake The effect of mistake in a contract of sales of goods is to void the contract. DUTIES OF BUYERS AND SELLERS By the provision of S.27 of the SOGA, it is the duty of the seller to deliver the goods and it is the duty of the buyer to accept and pay the price for the goods in accordance with the terms of their contract. By the provision of S.28 SOGA, except it is otherwise provided in the contract, delivery of goods and payment for same are concurrent conditions. That means the seller must be willing to deliver the goods in exchange for the price and the buyer must be willing to pay for the goods in exchange for possession of the goods. Rules as to Delivery 1.Whether it is for the buyer to take possession of the goods or it is for the seller to send them to the buyer depends in each case on the terms of the contract express or implied between the parties; S.29(1) SOGA. Apart from any contract express or implied, the place of delivery is the seller’s place of business if he has one. If he doesn’t have a place of business, the place of delivery is the seller’s place of residence. If the contract is for the sale of specific goods that to the knowledge of the parties is at another place, http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 10/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer that place would be the place of delivery. 2. Where under the contract the seller is meant to send the goods to the buyer but no time for delivery is specified, the time for delivery should be within a reasonable time; S.29(2) SOGA. 3. Where at the time of sale the goods are in the possession of a third party, there is no delivery until the third party acknowledges to the buyer that he holds the goods on the buyer’s behalf; S.29(3). However, nothing in this section would affect the operation of the issue or transfer of documents of title to the goods. 4. Demand or tender of delivery might be termed ineffectual unless it is made at a reasonable hour. What is a reasonable hour is a question of fact; S.29(4) SOGA. 5. Unless otherwise agreed, the expenses of and incidental to putting the goods into a deliverable state must be borne by the seller; S.29(5) SOGA. Delivery of Wrong Quantity or Mixed Goods S.30 SOGA 1. Where the seller delivers to the buyer goods that are less than the amount agreed upon, the buyer may reject them. If the buyer accepts them, he must pay for them at the contract rate; S.30(1). 2. Where the seller delivers to the buyer a quantity that is more than the amount agreed during the contract, the seller could either accept the quantity agreed upon and reject the rest. He could also choose to reject the whole quantity ;S.30(2). If the buyer chooses to accept the whole quantity, he has to pay for them at the contract rate. 3. Where the seller delivers to the buyer goods agreed upon in the contract but they are mixed with other goods, he may accept the goods according to the contract and reject the rest or he may reject the whole goods supplied;S.30(3) SOGA. 4. The provisions of this section are subject to any usage of trade, special agreement or course of dealing between the parties; S.30(4) SOGA. In the case of Polak and Faon vs George Cohen Ltd 1969 NCLR 433 the defendant contracted to sell goods to the plaintiff stating the quantity as “3500 tonnes, 10% more or less at buyer’s option”. The plaintiff after enquiry accepted the figure of 3500 tonnes 10% over 3500 tonnes. http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 11/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer The defendant supplied 3568 tonnes. The court held that where a contract of the supply of goods states the quantity followed by a given percentage “more or less”, the supplier is not bound to deliver the exact quantity but within given percentage of it whether more or less so that the delivery of the least quantity within the given percentage is good performance. Where the variance allowed is at the buyer’s option, and the buyer validly exercises his option, the supplier is bound to deliver the quantity so demanded by the buyer up to and including the greatest quantity within the percentage. It was also held that in the ordinary case where the buyer has no option, the damages for nondelivery are not damages for non-delivery of the quantity stated but for non-delivery of the least quantity within the given percentage. But it is otherwise where the variance so allowed is at the buyer’s option in which case, the damages are for non-delivery of the quantity demanded by the buyer. Installmental Delivery of Goods S.31 SOGA 1. Unless otherwise agreed, the buyer of goods is not obligated to accept goods delivered by installments;S.31(1). 2. Where there is a contract for sale of goods to be delivered by installment and to be paid for installment by installment, if the seller delivers defective goods for one or more installments or the buyer doesn’t take delivery or pay for one or more installments, the question of whether this would cause the repudiation of the contract or the payment of damages depends on the terms of the contract and the circumstances of the particular case; S.31(2). In the case of Mapleflock Co Ltd vs Universal Furniture Product Ltd (1934) 1 KB p.148 Parties entered into a contract for the sale of 100 tonnes of ragflocks. Delivery was to be made at the rate of three loads a week and each delivery to be separately paid for. The first 15 loads delivered were satisfactory but the 16th was not. In spite of this, the buyer took four more deliveries and then sought to repudiate the contract. The court observed inter alia: “…The true test would generally be the relation in fact of the default to the whole purpose of the contract. The main test to be considered are first, the ratio quantitatively which the breach bears to the contract as a whole. Secondly, the degree of probability or improbability that such a http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 12/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer breach will be repeated…” Thus, from the above, considering that 1 out of 20 installments was defective, the ratio is insignificant. Also, the probability that there would be a repeat of defective goods is very little since only one had been defective so far. Thus, the buyer cannot repudiate the whole contract. Rather, he only has a right to reject the defective installment. Another case is that of Regent OGH vs Francessco of Jenmy Ltd (1981) 3 ALL E.R @ 327. In this case, men suits were to be delivered by installments, the size of each installment/consignment being left to the plaintiff’s(the seller’s) discretion. One installment of 22 was delivered short of one and the buyer sought to repudiate the whole contract. It was held that in this circumstance, the buyer could not repudiate. Comparing S.30(1) & 31(2) the court observed that: “… if a misdelivered consignment is rejected, the result is to create a short delivery. S.30(1) and 31(2) in this respect, are not mutually consistent, one must yield to the other and it seems to me that the business sense of the contract of sales requires enough flexible provisions of S.31(2) to be applied in preference to those of S.30(1)…” Thus, considering the circumstances of the case, it was held that the buyer could only reject the defective consignment and not the whole contract. In the case of Mustapha and Co vs NCEI (1955) 21 NLR p 69, the terms of the contract provided inter alia for “delivery from factory January 1954”. Part of the goods left the factory in January 1954 and the remainder left early the following month as a result of which the buyer refused to take any part of the contract. The court held that the word “delivery” was to be construed in its normal as distinct from its legal or technical sense and that it meant that all the goods should leave the factory during January 1954. Since this had not been complied with, the defendant could not be compelled to accept even that part which arrived in January but could reject the whole because the contract was not severable. Delivery by Carrier S.32 SOGA 1. Where in pursuance of a contract of sale, the seller is authorised or required to send the goods to the buyer, delivery of the goods to a carrier, whether named by the buyer or not, for the purpose of transmission to the buyer, is prima facie deemed to be a delivery of the goods to the buyer; S.32(1). http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 13/15 12/23/2015 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer In the Case of Nads Imperial Pharmacy vs Siemgluse (1989) NLR under a contract of sale, goods were sent by S in Hamburg to M in Lagos. The goods arrived in Lagos and M was notified. When M went for collection, it was discovered that the goods were lost through some unexplained cause and so M sued S for the goods or the price paid. The court held that according to the provisions of S.32(1) SOGA, delivery of goods to a carrier is prima facie delivery to the buyer. Thus, in this present case, delivery to the ship, who acted as the carrier, was considered as delivery to M. Since risk passes with transfer of property, M would have to bear the risk since they have been prima facie delivered to him. 2. Unless otherwise authorised by the buyer, the seller must make such contract with the carrier on behalf of the buyer as may be reasonable, having regard to the nature of the goods and the other circumstances of the case. If the seller omits to do so, and the goods are lost or damaged in the course of transit, the buyer may decline to treat the delivery to the carrier as a delivery to the buyer, or may hold the seller responsible for the damages; S.32(2). 3. Unless otherwise agreed, where goods are sent by the seller to the buyer by a route involving sea transit under circumstances in which it is usual to insure, the seller must give such notice to the buyer as may enable the buyer to insure them during their sea transit. If the seller fails to do so, the goods shall be deemed to be at the seller’s risk during such sea transit; S.32(3) SOGA. Risk When Goods Are Delivered to a Distant Place Where the seller of goods agrees to deliver them at the seller’s own risk at a place other than that where they are when sold, the buyer must nevertheless, unless otherwise agreed, take any risk of deterioration if the goods necessarily incident in the course of transit; S.33 SOGA. Buyers right of examining goods S.34 Where goods are delivered to the buyer which the buyer has not previously examined, the buyer is not deemed to have accepted them unless and until the buyer has had a reasonable opportunity of examining them in order to ascertain if they are in conformity with the contract;S.34 SOGA. SHARE THIS: http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 14/15 12/23/2015 2 COMMERCIAL LAW 1 | The Jet Lawyer LIKE THIS: Like Be the first to like this. Related: LAW OF CONTRACT I November 11, 2015 In "200 level 1st Semester" CONTRACT SALES OF GOODS http://djetlawyer.com/commercial-law-1/#more-119 LAW OF CONTRACT II November 11, 2015 In "200 level 2nd semester" NIGERIAN LEGAL METHOD II November 11, 2015 In "100 level Notes" SALES OF GOODS ACT 15/15